Abstract

The British television series Downton Abbey (directed by Julian Fellowes) could be considered a media phenomenon without precedent. Since its release in 2010 and throughout its six seasons, it reached a global audience in over 220 countries. At a time when the father figure is dissolving, fading, or missing in the content of television series, the worldwide success of Downton Abbey features the image of Lord Robert Crawley (Hugh Bonneville), Earl of Grantham, the father of an aristocratic family in England. This article will analyze paternal image from its ontological and historical roots, considering truth, transcendence and goodness, as well as manifestations of paternal virtues. Given the fact that virtue is not easily measured, the analysis will show that a father's identity can be reflected in a series of virtuous actions, as manifestations of core virtues. These virtues are the basis for a quantitative content analysis of the seven episodes of the first season, through the application of a methodological tool for audiovisual analysis.

1. Introduction

Genuine interest in unraveling the great human dramas has been – and continues to be –a fundamental pillar in both mythological and historical dramas, the same ones that have been progressively brought to the big screen. At the beginning of the 21st century, this interest has successfully migrated to the new world of television series, perhaps because of the exacerbated advance of telecommunication technology in our days. Obtaining a defined captive market, such entertainment companies as Sony Pictures Television, Netflix and Masterpiece have managed to captivate a new group of viewers who eagerly await the new season or episode in their favorite series. The British series Downton Abbey (2010–2015) was no exception to this cultural phenomenon; it enjoyed an international audience with a presence in 220 countries during its six ambitious seasons. Found worthy of the most prestigious international awards of its kind – the Emmy Awards and the Golden Globes – Downton Abbey is considered the most expensive British series (per minute) of its time and the most watched in the history of North American television. But what is the reason for this overwhelming success? What relevance can be found in a series that recounts the life of an English aristocratic family at the beginning of the 20th century?

Lord Robert Crawley (brilliantly played by Hugh Bonneville) is the current heir to the noble title of Earl of Grantham and owner of the majestic castle known as Downton Abbey, where he resides with his wife Cora, and daughters Mary, Edith and Sybil, as well as the staff on duty, captained by Butler Charles Carson (Jim Carter). The plot revolves around the fate of the assets (not only material) that the Crawley family enjoys in the absence of an immediate heir, and in the context of the social and cultural developments that the turn of the century brought with it. This is coupled with historical events of great significance, such as the sinking of the Titanic (1912), the start of the First World War (1914) and the first outlines of suffrage feminism. However, the drama on display goes much further:

The backdrop of the plot of Downton Abbey is the paradigm shift or worldview. Downton Abbey is a tremendously effective way of telling what happens when you go from an orderly and hierarchical world, asymmetric in personal relationships, to a subjective world dependent on the will of each person, symmetrical in personal relationships. It tells of the passage from a paternal world to one of universal brotherhood, but without paternity. (Assirio Citation2015, 151–159)

As we will see later, the paternal functions exercised by Lord Robert Crawley are manifested in Downton Abbey through several acts of virtue. These suggest a deep analysis of his role as the father of a British aristocratic family in relation to his wife, daughters, extended family and, above all, service personnel, starting from a plot – similar to the classic series Upstairs, Downstairs – that so far has been little explored in audiovisual media (Esquire Citation2017). At a time marked by paternal absence (now maternal absence as well) in the domestic family environment (Hurtado Citation2014), television series have used this drama in their favor (González Gaitano Citation2012; Fernández Aguinaco Citation2013; Fuster Citation2015). This is reason enough for future research to continue systematic studies of the current paternal image in other equally successful, although antagonistic, audiovisual genres such as the series Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, Mad Men, Billions, among others. But before continuing, let us briefly sketch the ideological path that has put the paternal image into question in the past seventy years.

2. Crisis of fatherhood: ideological origins

Since the 1960s, the liberal family system has had a great impact in the West, particularly in the United States of America, Western Europe, Australia and, progressively, in Latin America. This system symbolizes the philosophical-political legacy of British thinker John Locke (Citation1965). In it, the spouses – husband and wife – have to assume a marriage contract between ‘equals’, headed by the father who assumes the exclusive role – or function – of economic ‘provider’ and nominal ‘head’ of the family as a civil institution. From this perspective, the father must focus mainly on three aspects embedded in family life: (1) the procreation and upbringing of his children as ‘rational and free’ beings; (2) his own technical preparation that allows him to manage his financial agenda in his chosen profession; (3) exemption from those burdensome domestic functions, typical of the traditional family model, which are delegated exclusively to the mother. In this way, what began to be known as the liberal family system, started to occupy a privileged place among the ‘marriage boomers’ and the ‘baby boomers’, both typical of the postwar period, particularly the 50’s and 60’s. Sociologists of the stature of Talcott Parsons, from Harvard University, were optimistic and supportive of the new Western family life (Parsons Citation1951, 116–119). Even William Goode wrote in 1963 the book World Revolution and Family Patterns, in which he argued that the ‘conjugal family’, based on Lockean liberalism and in consonance with Protestant asceticism, would be the cultural norm that would spread both in the industrialized West and in the underdeveloped or decolonizing countries (Goode Citation1963).

Half a century later, the Lockean model is now under observation. In other words, the liberal family system can be considered the cause of profound cultural disruption. Among other things, we see today low fertility rates and depopulation; low marriage rate; rise in de facto marriages; an increase in what was known in the past as ‘illegitimate births’; a high rate of orphans, unemployment and unmarried status; a total triumph of sexual radicalism, evidenced in the new contraceptive ‘culture’; a high rate of abortions and infanticides. In sum, we see a new totalitarianism that seeks to impose gender ideology at all costs, equal marriage ‘culture’, transgenderism (especially in children) and radical feminism (Andrews and Hurtado Citation2020, 127–139). This cultural change has come at an astonishing speed, particularly in the past 10 years. Why this change? What social or political forces is causing it? What further consequences are expected in the new millennium? The answers to these questions are based on three contradictions implicitly present in liberal ideology itself:

First: a deficient understanding of the concept of male human nature. John Locke certainly had a dark vision of man, whose most eager appetites (he thought) were favored in his desire for ‘self-preservation’ and thus, in his sexual ‘self-indulgence’ (Locke Citation1965; Yenor Citation2011, 20–23). The aspiration to have a large family, then, comes only from the desire to satisfy the sexual impulse, and from the Darwinian struggle to perpetuate one’s existence. The institutions that surrounded the old patriarchy – in that sense – managed to keep the males close to the family home in exchange for complete authority – despotic at times – over wife and children, as well as community and political environment. That was the male’s main civilizational motivation. Aware of this, the new ‘liberal project’ would not be compatible with this lifestyle at a political level, due to its strong monarchical orientation (scandalous in the eyes of modern thinkers). Locke considered it necessary to put an end to this patriarchal rationality, and therefore, to the family style that sustained it. The family home would then represent the limit to the father’s authority as a parent. But outside the home, his role as an individual citizen would radically evolve, mostly in the first industrial revolution, commonly located at the end of the 18th century, to what we now know as the image of the breadwinning father.

However, this ‘soft patriarch’ image showed its vulnerability in no time. For Locke, women have a natural instinct for attachment and protection towards children in the domestic environment. The man, on the other hand, once exclusively incited to exercise his authority in this area, would realize an irrefutable truth: a woman knows how to exercise this authority in the domestic sphere in a natural way. Therefore, men had to accept these living conditions as the basic premise of the new family functioning. However, the same liberal ideology affirmed over time that the price that women paid in this model was very high. For this reason, in order to achieve the desired equality that liberalism promised to all individuals, women would have to overcome their maternal ‘instincts’, weakening their emotional ties (towards the husband and children) in search of their own self-development. It is here that the contractual ‘idea’ of marriage breaks down, for as women gave up their innate maternal purpose, the male's paternal purpose slowly wakened. In that sense, John Stuart Mill was one of the first thinkers to describe the now known feminist imperative (Mill Citation1869 [2008]) in the mid-19th century. Its social and cultural acceptance would depend solely on what he himself called ‘fashion’.

Second: the limited functions of the liberal family. The liberal family system promoted by Locke was based on a ‘voluntary pact’ between men and women that placed reconciliation of interests and properties in common in the center of their dialogue. This was not far from patriarchal rationality, in which the economic life of men and women was completely merged, characterized by developing ad intra a wide range of activities productive in themselves (Carlson and Hurtado Citation2019, 79–95). Hence its well-known economic self-sufficiency. In the liberal-Lockean scheme, a similar balance was achieved, although with some nuances. The most relevant novelty, in that sense, was the dispossession of a considerable portion of economic autonomy, property being the first affected. That is, since the primary purpose of the liberal family encompassed only the procreation and socialization of young children – their upbringing as free and rational individuals – to speak of a robust domestic economy would be absurd. Although the implications of this gradual weakening process were not perceived by Locke, it is clear that his liberal family model would have a central place in the future capitalist industrial order. Already in the 1950s, Parsons himself – channeling Locke – celebrated the emergence of this new family model due to its ‘specialized’ nature. At the same time, female suffrage (or first-generation feminism) contributed to the progressive transformation of the traditional family, from an economic-political unit into a consumer one.

Added to that, the gradual disappearance of the ties to the extended family, and with it, the loss of its centrality as a principle of community unity in general, allowed the ‘nuclear family’, as it came to be called, to concentrate its efforts on two basic and irreducible functions: (1) procreation and socialization of children; (2) the emotional stability of adults. Regardless of the internal logic of these two, Parsons was doubtful that these functions would prevail, perhaps because of their strong psychological orientation, as summarized by Philip Abbott in his book The Family on Trial (Abbott Citation1981).

Third: its dependence on coercive social engineering. Having said all this, in order to reshape the political order, Locke concluded that the natural family would have to be redesigned. Human beings are not born ‘rational and free’ but have to become so with the help of their environment. For this reason, the English thinker invented the previously mentioned ‘nuclear family’, whose main function would be to model the new ‘individual’, subject to the new liberal order. In its founding stage, this task was relatively similar to the later efforts that tried to mold the ‘Soviet man’, the ‘fascist man’, even the ‘feminist woman’, all of them of an indisputable totalitarian nature. But it was Mill who took the first step in that direction, postulating as a desirable goal for every infant to become ‘free and rational’, always in his constant search for his own ‘individual development’, in pursuit of a supposed ‘perfect equality’. Once this new model of the ‘egalitarian family’ was proposed, Mill promoted it as the only desirable one, and since it does not occur ‘naturally’, it would have to be imposed, coercively if necessary (Mill Citation1869 [2008]).

Eventually, it was the liberal philosopher T.H. Green who took the next step in this discursive line, suggesting that the ‘institutions of civil life’, that is, the state, should ‘make it possible for a man to be freely determined by the idea of a possible self-satisfaction’ (Green Citation1967, 32–33). This is confusing language that elevates the concept of ‘self-realization’ to the degree of ‘central liberal principle’. For his part, the American philosopher John Rawls took this argument to the next level with his search for the famous ‘distributive justice’, or its ‘fair opportunities’. In that sense, the search for self-discovery of each individual failed in the context of the traditional family, but not within the framework of the new liberal family, at least in theory. Perhaps for this reason, Rawls decreed his famous phrase: ‘Will the family be abolished?’ (Rawls Citation1971, 511) Almost sixty years after it was formulated, the idea of equal opportunities in the family context has led us in this direction, together with the clear weakening of the paternal image within and without the home.

3. The quest for the image of the father: objectives and hypotheses

The main objective of this paper is to analyze the image of the father seen in Lord Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham in the series Downton Abbey. Specifically, the active presence of five fundamental virtues will be analyzed, namely, self-control, joy, work (or industriousness), generosity and responsibility, as seen in the character’s actions in front of his relatives (see section 4). It is to be expected that Lord Crawley’s virtuous behavior will be considerable and worthy of imitation, in the historical moment in which the figure of the father seems to be very present in the acclaimed television series (Fuster Citation2015). For this reason, we start from the hypothesis that the father analyzed in this work manifests – and therefore promotes – one or more virtue in each scene of the series.

We will develop a theoretical framework that explains the paternal image, understood from the virtuous acts of the father, but, before doing so, it is necessary to reflect on the essence of fatherhood from an anthropological perspective. To do this, one has to go back to the concept of human person, because one as the father of a family is a male, but it is also true that a male is first a person. Therefore, the fatherhood of a man cannot be separated from his human-persona condition, that is, from his personal identity and his historical identity.

3.1. Personal identity: a ‘who’ in front of others

Paternal identity initiates in personal identity, placing us in the field of ontological identity, which refers to the ‘given’, the ‘original’ or the ‘innate’ (Martínez Priego, Anaya Hamue, and Salgado Citation2014, 75–85). We are talking about the most proper and specific nucleus of each human being: his who:

The person is unique and unrepeatable, because he is someone; not just a what, but a who. The person is the answer to the question who are you? Being a person immediately means to be a who, and being a who means to be with a name. Thus, a human is an animal that uses a proper name, because the name designates the person. (Yepes and Aranguren Citation2006, 64–65)

In effect, the human person ‘receives’ existence, since he does not make his own self. In that sense, being a person is being ‘a who’ that cannot be understood without some notes that characterize his identity. Yepes and Aranguren (Citation2006, 62–70) listed five constituent notes of personal identity showing a unitarily personal being, namely, intimacy, manifestation, dialogue, donation and freedom:

Intimacy: refers to the interior space of the person, in which we find ourselves through reflection. It is ‘the way of being that does not need to assimilate external elements or possess them’ (Polo Citation1999, 157). From there, the human being is capable of self-possession and, therefore, capable of opening up to others and bringing the novelty of their own existence (Ricoeur Citation2006; Wojtyla Citation2008).

Manifestation: when we speak of the human capacity to ‘open up’ to others, we are referring to the concrete way in which the person ‘manifests’ (Polo Citation1999, 159), which is expressed through the body in terms of language and human acts. These allow human beings to manifest ‘who they are, actively reveal their unique and personal identity and make their appearance in the human world’ (Arendt Citation2005, 208).

Dialogue: personal identity is dialogical. That is, each personal being is presented as a ‘who’ before another ‘who’ with whom it shares what it ‘is’. It supposes being recognized by the other as an irreplaceable who, since we are ‘in front of others’ in a radical way, a fact from which the richness of the relationship starts (Alvira Citation2000).

Donation: but your relationship is not enough to build human life. It is necessary to achieve more: it is necessary to give oneself to others, which presupposes knowing oneself as a gift, since the gift, if it is personal, ‘leads […] to being a gift with respect to the one who gives, and also to be one with respect to the one who accepts’ (Sellés Citation2011, 614). For this reason, a person can only give himself – donate himself – if he knows himself as a gift, if he accepts the gift that was given to him at his origin.

Freedom: the ‘gift of oneself’ is impossible without freedom. Personal freedom is unlimited because, although it is typical of a finite being, it can always be expanded, showing that the human person is, therefore, unrestricted openness (Sellés Citation2011), with the ability to control what he wants (Ricoeur Citation2006). The free person updates his identity through his actions in front of others, from his freedom, which makes his personal growth possible.

3.2. Historical identity: time and space

The possible openness to others, personal and free, opens up a space to another fundamental dimension for the construction of personal identity: historical identity (Martínez Priego, Anaya Hamue, and Salgado Citation2014). It unfolds in a specific space and time, in the midst of a network of specific personal relationships, with a specific genetic code, a language, and an evolving social conscience. With this, it can be affirmed that personal identity depends on historical identity, since this ‘can only be articulated in the temporal dimension of human existence’ (Ricoeur Citation2006, 107). This opens up a specific number of possibilities for participation in the construction of the world of human beings.

Indeed, without being authors of our own existence, we can be co-participants in human reality (Hurtado Citation2014), endowing it with a ‘why’ that refers to our own action (Ricoeur Citation2006). But the possibility of human co-participation in the construction of one’s own historical and cultural reality presupposes a certain initial in-identity (Innerarity Citation1993, 371–174), which gives reason to the possibility of the habit that tends to virtue. In other words, ‘by being-in-time, man lives in an installation that changes with its own passing and in which man projects and carries out his own life’ (Yepes and Aranguren Citation2006, 72).

Now, the notion of time reminds us that the human being had a past and therefore a tradition the memory of which remains (MacIntyre Citation1981). Without a memory of the past, it is not possible to project the future, since the characteristic of intelligence is to imagine what good would be like, starting from the known. ‘Life is an operation that is carried out forward’ (Marías Citation1973, 91). With this, it is not intended to downplay the present: ‘men want to stay […] their passing never passes […], rescuing time, reliving what is true, these are constants in human behavior’ (Yepes and Aranguren Citation2006, 73).

For its part, space tells us about the concrete place ‘where I appear to others as others appear to me, where men do not merely exist as other living or inanimate things, but make their appearance explicitly’ (Arendt Citation2005, 225). It is here where language and the human act gain their respective relevance (Aguilar Rocha Citation2007), creating the ‘space’ – not only physical – which humans tend to inhabit (Alvira Citation2020, 35–50).

3.3. Paternal image: virtue in front of the child

Intimacy, manifestation, dialogue, donation and freedom are the notes that, insofar as they belong to personal identity, can be considered as characteristic of the longed-for paternal identity, from its historical dimension. In other words, we are talking about their personal deployment in a specific space and time, in a specific context in which these notes are manifested from the person to his peers. Who will these ‘peers’ be? We are talking about the family home (Hurtado and Galindo Citation2019), constituted in principle by the father, the mother and the children, because let us remember that the child is not possible without the father, but neither is the father possible without the mother (von Hildebrand Citation2019).

Now, returning to the parent-child relationship, it is important to point out that the persons involved need each other reciprocally (Polaino-Lorente Citation1995, 295–316). The personal identity of the child is identified with the personal identity of the parent, since every human being, ‘never ceases to be a child: he can become a parent, but being a child constitutes him (Polo Citation1995, 324). ‘The reality of the being of the child ‘can’ get to the depths, responding forcefully to the question: who am I? one can answer: ‘I am the parent of my child’. The child, for his part, is justified before others when he affirms: ‘I am my father's son’. However, both answers present a certain distance in the existential level, since the responsibility assumed by the father towards the son has a certain hint of one-sidedness. In other words, the father is built in front of the son, which can generate either security or insecurity in both. The son has to abandon himself to the arms of his father, trusting his personal growth, even when the father is not sure of his own identity.

Perhaps in this dynamic lies the transcendent dimension of parenthood, which overcomes its biological roots to give it a profound existential meaning. Indeed, all human beings come into the world one through another (Santamaría Citation2000). We know, or should know, whose children we are. Awareness of one's own paternity generates (in a man) a recognition of his own being ‘in the child’, giving meaning to his own existence aiming towards personal improvement. It is a new way of overcoming the limits of his personality to remain in the child, giving a greater scope to what one ‘is’ and what one ‘can’ become (Arendt Citation2005). In other words, the search for the good of the father – the search for virtue – translates into the happiness of the child, and therefore that of the father. With this, the exclusiveness of the relationship between father and son can be affirmed, one and only. One is always the father of one’s son, not according to time or circumstance, from which it follows that fatherhood does not depend on the will of the father, but mainly on the need of the child (Malo Citation2015), who accepts his filiation by recognizing that he needs the father to live (Assirio Citation2013).

***

As we have seen, both fatherhood and filiation imply a permanent relationship. This does not change when the son leaves the family home in search of his own life, or when he reneges on his parents because of mistakes made in the past. Fatherhood, therefore, refers to the original fact of one's own existence, which is rooted in the life of the parents themselves. Consequently, the foundation of fatherhood finds its raison d’être in the identity of the son – of his who – which is confirmed in its real origin that it is always relative to the life of his parents.

[This] relationship, insofar as it is constitutive, foundational and original, inevitably refers to the origin of one's own being, enlivening itself in its roots, challenging man from them. In the lives of the father and the child, paternity and filiation have a vocation of eternity, consequently, they are stronger than the death of man which they always survive. (Polaino-Lorente Citation1995, 303)

To this must be added the notion of the good that develops in the realm of human action, the concrete good that must be realized in the virtuous act. The goodness of the father, his virtue, has at its end perfection itself, the same that must overflow into the perfection of the son: this is donation. Through it, paternal love returns to the child – gratuitously and benevolently – the gift of himself, his own existence. The father's love becomes ‘donative’ love that he himself recovers in a broad and full way in the life of the son, a fact that is also his greatest gift: to be co-creator of his son (Polaino-Lorente Citation1995, 295–316; Hurtado Citation2011).

The virtue of the father has a ‘multiplier’ effect on the son, because they both know that neither of them is capable of absolute goodness or perfection. All human growth is possible thanks to this original ‘indetermination’, justifying what Rodríguez Luño calls ‘the habit of good choice’ (Citation2006, 214). However, the conquest of virtue is not possible alone: it takes an intimate environment that generates the confidence necessary to achieve any educational purpose. We are talking about the family home, which is also the foundation of the community spirit that enlivens the social mechanism (Athié and Hurtado Citation2020). In effect, the family and the community are necessary for the human person to acquire the capacity for discernment and choice that must be incorporated as ‘good operating habits’ that bring about the achievement of vital fullness (Naval Citation1997, 761–778). Therefore, it is in the midst of domestic family life where the hard core of one’s own personality and the development of virtues that build one’s identity are constructed (Hurtado and Galindo Citation2019).

4. Content analysis on some virtuous actions in the father figure: Downton Abbey (1st season)

Virtue, understood as a good habit that tends to perfection, is not easily measurable. Therefore, we will refer to the virtuous actions performed by the character in question in front of others. Virtue, as a human act, has a qualitative value that is articulated as the ‘best-worst’ binomial. For the purposes of our research, it is interesting to see how the paternal identity of Lord Robert Crawley is manifested in his virtuous acts, namely, self-control, joy, work (or industriousness), generosity and responsibility, which represent a type of human disposition that points towards a full life of action. (Corominas and Alcázar Citation2014). The structure of the analysis is not intended to be absolute in itself, but rather a practical and orderly approach to observing the attitude of the father in certain circumstances and in front of specific people, that may serve as a ‘spearhead’ for future analyses of other parental images in cinema and in television series.

4.1. Methodology

The methodology used in this research is audiovisual-content analysis, based on previous experiences applied to the media in general (Porto Pedrosa Citation2013, 5–79) and television series in particular (Vázquez Citation2011), in order to show the values transmitted by television products. Several authors agree that television is capable of modeling people's behavior (Samaniego, Pascual, and Navarro Citation2007, 307–328) – our strengths and our weaknesses – and influencing it (Del Río, Álvarez, and Del Río Citation2004).

Downton Abbey has been studied through approaches that range from a comparative analysis to historical series from other countries (Sánchez Burdiel Citation2014) to the broadcasting of the English character and the nostalgia it fosters (Baena and Byker Citation2015). In any case, we have not seen a published analysis that addresses the manifestation of virtuous actions through content. Talking about Downton Abbey as a television series is not entirely accurate, since today it can be streamed through Amazon Prime Video and its consumption is no longer strictly through television. However, this particularity does not interfere with our study, which does not analyze the perception of this audiovisual product, but its content. In this sense, this research has a clear quantitative application and has certain advantages:

While qualitative methods, by using natural language, are better to gain access to other people's world of life in a short time, quantitative methods are better to conduct positive science, that is, they allow clear, rigorous, and reliable data collection and allow empirical hypotheses to be tested in a logically consistent way. (Sierra Bravo Citation1998, 25)

To be consistent with the essence of the selected technique and, making use of experiences such as those mentioned, we have carried out a content analysis whose basic unit has been each of the scenes in which the father, Lord Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham, appears in the first season of the series. The scene is the most important element of a script (Field Citation2005, 162) and we can define it as the unit of dramatic action (that is, endowed with an approach, a middle and an outcome), determined by a criterion of spatial-temporal location. Thus, every time space or time changes – or both variables – in the film or series content, the scene will be changing (Sánchez-Escalonilla Citation2014, 188).

Based on these criteria, 318 scenes were counted in the first season of the series: 48 in the first episode, 36 in the second, 42 in the third, 41 in the fourth, 46 in the fifth, 42 in the sixth and 63 in the seventh. A first count established by the authors during the viewing for the analysis was adjusted to conform to the number of scenes counted by Amazon Prime Video, the streaming platform where the series is hosted.

To each of these units we have applied a content analysis protocol accompanied by the complete transcription of the scene and composed of the following analysis categories:

Unit number,

Episode number,

Description of the scene,

Duration of the scene,

Name of each one of the characters that appears with the protagonist,

Group and subgroup of each of the characters.

Group 1: family

Family that lives in the house: Lord Grantham, his wife Cora and their three daughters: Mary, Edith and Sybil.

Family that lives outside the house (outside Downton Abbey): Violet, mother of Lord Grantham; Isobel and Matthew, distant cousin and her son, respectively; and Rosamund, sister of Lord Grantham, who appears in the last episode.

Friends or acquaintances of the family: those who visit the family at home: Kemal Pamuk, Evelyn Napier and Dr. Clarkson.

Group 2: servants and acquaintances

Employees who do housekeeping chores and who live at Downton: Mr. Carson, Mrs. Hughes, John Bates, O'Brien, Mrs. Patmore, Thomas, Anna, Daisy, William, Gwen and Branson.

Friends or acquaintances of the household: people who have a friendship, family or other relationship with employees at Downton Abbey: Molesley, Matthew's butler, his father and Charles Grigg, Carson's ex-partner who goes to the house to blackmail him.

Attitude of each of the characters,

Motivation of each of the characters,

Group belonging to the character with which the greatest interaction occurs.

Manifestation of virtues in the figure of the father:

Yes,

No,

Core virtues that are manifested in virtuous actions in the figure of the father. In this category one or more virtuous actions may be selected.

Self-mastery (core virtue): ‘strength to open oneself to the outside world of things and people’ (Corominas and Alcázar Citation2014, 25). It can manifest itself through these virtuous actions:

Self-control: serenity seeking to understand information and acquiring opinions and convictions, as well as the ability to control impulses.Footnote1

Self-knowledge: process by which the human person understands change, accepts his progress and limitations and opens up to relationships with others (Delors Citation2013).

Humility: recognition of ‘one’s own inadequacies, qualities and capacities, and [using them] to do good without attracting attention or requiring the applause of others’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 361).

Simplicity: acting and speaking in intimate connection with what you think and want, and appearing before others as you really are, without double-mindedness (Tomás de Aquino II-II, Citation2010, q. 109, a. 2, ad. 4).

Personal balance: moderation, equanimity, good sense in judgments and actions that allows those who possess it to live with internal order.Footnote2

Serenity: vital attitude in the face of temporary vicissitudes that aims to guide man on the way to govern his own life (Soto-Bruna Citation2002, 655–674).

Truthfulness: virtue that inclines the person to tell the truth and to manifest himself through his actions and words, as he is internally (Tomás de Aquino II-II, Citation2010, q. 109, a. 1 C; to. 3, ad 3).

Sincerity: to show, if appropriate, to the right person and at the right time, what one does, thinks, feels, etc., ‘with clarity, regarding their personal situation or that of other’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 165).

Joy (core virtue), understood as ‘the synthesis of man’s aspirations […] fruit of life according to virtue’ (Corominas and Alcázar Citation2014, 23) and, therefore, visible in these virtuous actions:

Optimism: trusting in one's own qualities and those of others; distinguishing the positive from possibilities and obstacles and facing them with ‘sportsmanship and joy’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 81).

Positive attitude: always trying to see the good in things, even when there are difficulties, without falsifying or idealizing reality (Corominas and Alcázar Citation2014, 23),

Peace: on a personal level, it is an inner state devoid of negative feelings that supposes tranquility with oneself and with others.Footnote3

Work or industriousness: core virtue that shows ‘the external projection of the person who uses things and perfects them according to their needs’ (Corominas and Alcázar Citation2014, 24). The demand to work well is manifested in one or more of these virtuous actions:

Commitment to a job well done: industriousness that is typical of someone who ‘diligently performs the activities necessary to reach […] maturity […] in professional work and in the fulfillment of other duties’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 253).

Effort: ‘intimate dedication, which goes beyond duty, that the subject makes in the achievement of something that interests him […]; the desire to carry out well-done work and to, if necessary, leave their mark’ (Benavente Citation2003, 19).

Strength: to resist and endure inconvenience and to give in with courage ‘to overcome difficulties and to undertake great efforts’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 63).

Generosity: core virtue that supposes the culmination of human relationships and ‘consists not only of giving things but of giving oneself’ (Corominas and Alzázar Citation2014, 123). Hence, the virtuous actions in which it is manifested are these:

Loyalty: accepting the implicit links in adhering to others and reinforcing and protecting ‘over time, the set of values they represent’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 235).

Fidelity: a ‘virtue that allows one to keep what one has promised’ (Tomás de Aquino II-II, Citation2010, q. 110, a. 3, ad. 5). It is the congruence of what is said with what is done; it rests on the honesty that should reign among men (Tomás de Aquino II-II Citation2010, q. 88, a. 3, ad. 1).

Appreciation: ‘a quality linked to maturity; it is the recognition of the value of what someone has done for another, and allows establishing strong ties between people’ (Gomá Citation2013).

Forgiveness: a ‘fundamental attitude that makes the person be inclined […] to the “cancellation” of the “balance of guilt” of an offender and to affirm him as a person’ (Crespo Citation2004, 129). It has the character of a gift.

Respect: the habit of considering the dignity of people, as unique and unrepeatable beings, with intelligence, will, freedom and capacity to love, as well as their rights according to their condition and circumstances (Corominas and Alzázar Citation2014, 125).

Understanding: the desire to help other people according to one’s circumstances; to understand them and see, from their point of view, the situation they face (Corominas and Alzázar Citation2014, 126).

Responsibility: core virtue; reflection of the personal maturity of those who are capable of living their freedom, and who ‘assume the consequences of their intentional acts, the result of the decisions they make or accept’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 131). Thus, it can manifest itself in the following virtuous actions:

Commitment to the truth: attitude of the person who seeks to do justice to reality (Spaemann Citation1998).

Coherence: knowing what one's own objectives are, why one acts in one way or another, the connection between more profound desires and what one actually does.Footnote4

Flexibility: adapting ‘behavior with agility to the circumstances of each person or situation, without abandoning the criteria of personal action’ (Isaacs Citation2003, 219).

Final Comments: Before closing this section, it is convenient to emphasize the unique nature of this study. Although the topic analyzed, human virtue, belongs to the Humanities, it is approached in this paper from the perspective of communication and from a quantitative methodology. The fact that the initial theoretical-humanistic section now gives way to a more quantitative one could give the impression of incoherence; However, we consider this distinction necessary in order to delve into such a profound issue and, ultimately, to advance the investigation of television productions beyond the merely communicative aspects that they offer.

4.2. Data analysis

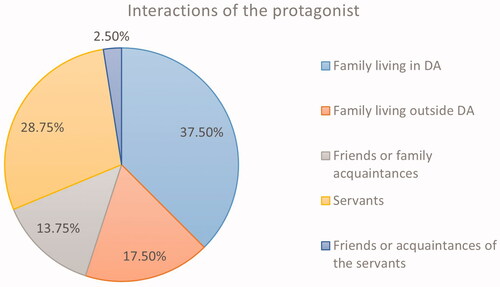

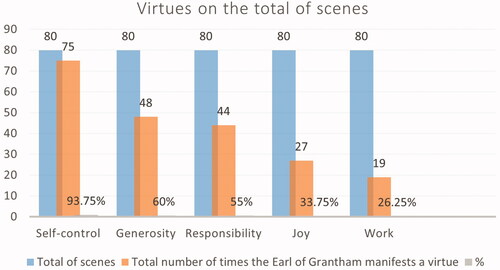

In total, the first season of Dowton Abbey contains seven episodes, which in turn, as we mentioned in the methodological section, are subdivided into 318 scenes (48 in the first episode, 36 in the second, 42 in the third, 41 in the fourth, 46 in the fifth, 42 in the sixth and 63 in the seventh and last episode of the season). In those seven episodes, Lord Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham, appears in the first episode in 22 scenes; in the second, in 9; in the third, in 7; in the fourth in 8; in the fifth, in 9; in the sixth, in 9 and, in the seventh, in 16. In total, the father in the series appears in 80 scenes throughout the first season of Downton Abbey. The moments in which the Earl of Grantham, as a father, manifests each of the virtues, taking into account that in our analysis we have considered that more than one virtue could appear in the same scene, can be seen in .

Graph 1. Number of times the father manifests a virtue, graphed on the total number of scenes. Source: our own.

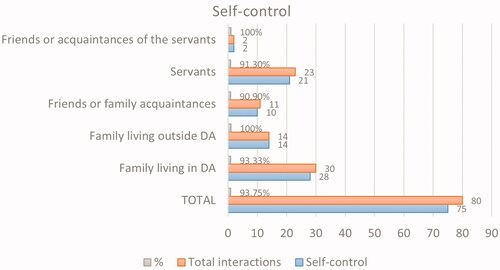

4.2.1. Virtuous actions related to self-control

Of all the core virtues analyzed, the most represented is self-control, which appears in 75 of the 80 total scenes. Together with self-control, of all the virtuous actions analyzed – temperance, self-knowledge, humility, simplicity, personal balance, serenity, truthfulness and sincerity – the one that the father most often shows is serenity. This is especially in the scenes where he interacts with Bates, his valet, even when Robert Crawley wants to know more about his employee's past and Bates refuses to reveal that secret information (episode 7: scene 8).

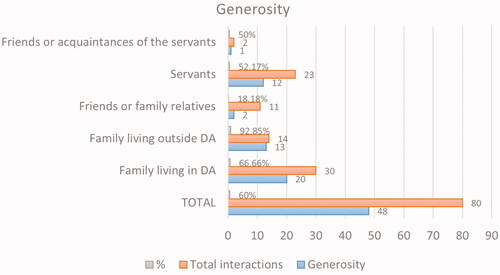

4.2.2. Virtuous actions related to generosity

This is followed by generosity, with a total of 48 manifestations in the 80 scenes in which the father appears in the entire first season. Set within the context of generosity, understanding appears as the most represented virtuous action, something that Lord Grantham manifests throughout the season with his family and also with the servants. An example of this last interaction is found in his understanding towards Bates, visible in multiple scenes, and towards other employees when they have performance or ability problems (see Lord Grantham in the face of Mrs. Patmore’s blindness problem in scene 7 of the last episode). This is seen even when there is a chance losing them because they find a better job (see episode 7: scene 12). In total, understanding is manifested in the figure of this protagonist of Downton Abbey in 27 of the 48 scenes in which Lord Robert shows generosity.

Respect is worth mentioning – as a second manifestation of virtuous action related to generosity – in the Earl's treatment of Matthew, his distant cousin, whom he treats as an equal even though Matthew comes from a lower social stratum than his own. This can be seen in the continuous allusions to Matthew having a profession, something inappropriate and unusual for the nobility at that time. In this sense, the example that the father gives to his daughters is significant. Little by little, they overlook this social difference when they see how their father integrates his distant cousin. In all, this protagonist of Downton Abbey shows respect in 25 of the 48 scenes in which he expresses his generosity.

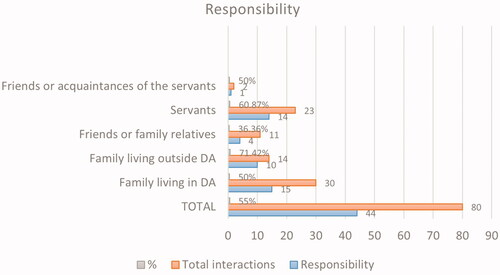

4.2.3. Virtuous actions related to responsibility

As the third most represented core virtue in the figure of the father, we find responsibility; it appears in 44 of the 80 total scenes of the first season. Responsibility can be manifested in three virtuous actions: through commitment to the truth, which constitutes half of the scenes starring the father in this category; coherence (43.18% of the scenes) and flexibility, which is manifested in 31.81% of the scenes.

The type of virtuous action linked to responsibility that stands out the most in Lord Robert is that of commitment to the truth – with a foundation in honor. This is demonstrated in his way of facing difficult situations, from his commitment to confessing to Mary that Patrick died in the sinking of the Titanic (episode 1: scene 3) to losing his fortune because of having no male heir.

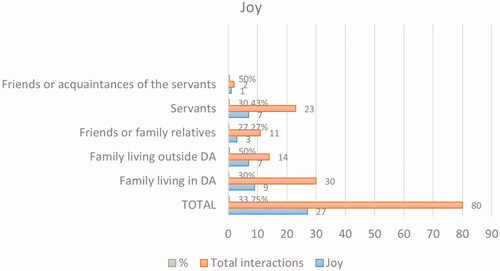

4.2.4. Virtuous actions related to joy

The fourth most common virtue is joy, found in 27 of the 80 total scenes in which the father appears during the first season. When referring to joy, which is manifested in virtuous actions that denote optimism, positive mood and peace, we note that in Lord Grantham all three are manifested with similar percentages: optimism and positive mood, each in 35% of scenes, and peace in 30%. Despite difficult situations in the political, economic and family context, Lord Grantham always maintains a positive disposition, above all. An example of this appears in scene number 16 of episode 1, where Lord Grantham makes Carson see that having Bates working for Downton is not as bad as he believes, and allows Bates to continue with his job, instead of firing him and getting carried away by Carson's attitude towards the valet. We can also observe these virtuous actions when Lord Grantham learns of his wife's unexpected pregnancy, in scene 3 of episode 7. In it, the Earl is happy despite the uncertainty the moment, related to the risks of a pregnancy at his wife’s advanced age, and the economic instability that the family is going through. In general terms, we observe that Lord Grantham remains constant in virtuous actions that show the virtue of joy throughout the first season, except in specific cases, such as the death of the baby, or before the imminent start of the war.

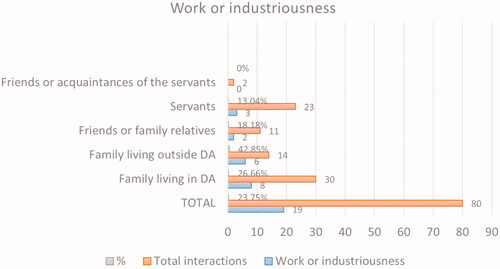

4.2.5. Virtuous actions related to work or industriousness

The virtuous actions that appear the least are those related to the core virtue of work or industriousness, which are expressed in 21 of the 80 total scenes. The three main virtuous actions showing industriousness are: commitment to a job well done, effort and strength. Of them, the one that is repeated the most is strength, which appears in 47% of the scenes in which we see virtuous actions in Lord Grantham, referring to work. Although Lord Grantham is not a typical worker in the contemporary sense of the term, he must remain strong to preserve not only his assets, but also the calm that allows him to develop the best strategy so as not to lose the family fortune.

One aspect that can help clarify the perception of work, as a paid activity, that the protagonist of Downton Abbey has, is the negative conception that in the socio-historical context of the series was held about the simple fact of having a profession. The Earl of Grantham himself shows this in scene 7 of episode 1 where, when speaking with George Murray, they both discuss Matthew Crawley’s profession, as a lawyer, and that of his father, as a doctor. Both Murray and Robert Crawley are dismissive of those professions or of any job in general. The same happens at a dinner at Downton, with Matthew and Isobel (episode 2: scene 3), in which they begin to get to know each other and the most shocking detail for the Crawleys is that Matthew works as a lawyer and also divides his week into business days and weekends. The position of the aristocracy regarding work as an activity is clear: it is not typical of their class.

4.2.6. Core virtues and interactions

We mentioned earlier that virtues do not manifest themselves except in interaction with others. Therefore, part of our study focuses on analyzing how the protagonist manifests each virtue in his interactions with different groups. To do this, we have carried out the necessary cross tabulation of variables to obtain, on the one hand, who the protagonist mainly interacts with in each scene and, on the other, which virtues are manifested by the Earl of Grantham before of the characters of each group.

In the first place, if we identify each scene with an interaction of the protagonist, we see that the total number of interactions adds up to 80. Of these, 30 (37.5%) occur with the members of his family (wife and/or daughters) who live at Downton Abbey; 14 (17.5%) with relatives living outside the home (Violet, his mother, Matthew, his distant cousin and Matthew’s mother Isobel) and 11 (13.75%) with other friends and family acquaintances. In total, in 55 of the 80 scenes starring Lord Robert (68.75%), he appears interacting with people from his family circle, friends or acquaintances who visit him for any reason. The same character interacts with his servants on 23 occasions (28.75%) and with one of their friends or acquaintances in two (2.5%). While he interacts in 55 scenes with his family, friends and acquaintances, he does so on 25 occasions (31.25%) with the servants and their friends or acquaintances ().

When carrying out a review of the core virtues that are manifested in virtuous actions of the protagonist in each interaction, we see self-control in all the scenes in which he appears, except in five. These are the second-to-last scene of the first episode, in which the Earl of Grantham expresses to Bates his anger at the Duke of Crowborough in a single comment; the third scene of the second episode, in which his daughter Mary introduces him to Kemal Pamuk, with whom she is in love, and Lord Grantham makes some humorous comment; and the second, the fifth and the sixth scenes of the sixth episode. In the second scene of the sixth episode, the protagonist reprimands his daughter Sybil for going to meetings of the liberals; in the fifth, he indirectly tells her that he is aware that some servants are conspiring with her to attend the meetings behind his back; and, in the sixth, Robert Crawley, like his wife and daughter Mary, shows astonishment that his daughter Edith is invited by Sir Anthony Strallan to a concert.

Overall, we can say that self-control is manifested by the protagonist in 93.33% of the scenes in which he interacts with his wife and daughters; in 91.30% of the interactions with their servants; in 90.90% of the scenes in which he interacts with his friends or acquaintances; and in 100% of those in which he interacts with friends or acquaintances of the servants ().

Regarding generosity, the protagonist manifests virtuous acts related to this core virtue in 60% of the scenes. Specifically – as shown in the chart – our analysis concludes that Robert shows generosity in 66.66% of the interactions with his wife or daughters; in 92.85% of the interactions with those who live outside; and in 18.18% of those with their friends or acquaintances. However, he is generous in 52.17% of the interactions with his servants and in 50% of those scenes in which he interacts with their friends or acquaintances. If we group the people who interact with the father into either family and friends or servants and friends, we obtain that, while with his family and friends he shows generosity in 64.40% of his interactions; with the servants and his friends he shows this core virtue in 52% of the scenes ().

Third, we find that virtuous actions in relation to responsibility appear in 55% of the scenes. If we look at the different recipients of Lord Grantham’s interactions, we find that he manifests this core virtue in two thirds (66.66%) of the scenes in which he interacts with his wife or daughters – a group of relatives who live with him at Downton Abbey – while the percentage increases to 71.42% in the group of relatives who live outside the home. With his friends or acquaintances, Lord Robert shows responsibility in 36.36% of the scenes. The results are more homogeneous in the group of servants: with his servants, the Earl shows responsibility in 60.87% of the interactions and, with their friends, in 50%. By establishing the division of Group 1 (relatives, friends and acquaintances of the protagonist) on the one hand, and Group 2 (servants and friends or acquaintances of this) on the other, we find that the protagonist shows responsibility in 52.72% of the interactions with Group 1, and in 60% of the scenes in which he interacts with Group 2 ().

Graph 5. Manifestation of responsibility by the father, divided according to those with whom he interacts. Source: our own.

As for virtuous actions derived from joy, these are manifested in 33.75% of the total scenes (27 out of 80). This protagonist of Downton expresses joy in 30% of the interactions with his closest family; in 50% of interactions with their family members who do not live at Downton Abbey and with 27.27% of their friends and acquaintances. Regarding servants, Robert manifests joy in 30.43% of the interactions with his servants and in 50% of the scenes in which he interacts with friends or acquaintances of them. Overall, the protagonist expresses joy in 34.54% of the scenes with Group 1 and in 32% of the interactions with Group 2 ().

Graph 6. Manifestation of joy by the father, divided according to those with whom he interacts. Source: our own.

The last of the five virtues analyzed in order of frequency of appearance is work or industriousness, with its virtuous actions manifested in 23.75% of the protagonist's interactions. If we break that number down into target groups of his interactions, we find that, with his family members living with him at Downton, work appears in 26.66% of interactions; with relatives living outside of Downton in 42.85%; and with friends or acquaintances in 18.18%. In interactions with the servants, Robert manifests this core virtue in 13.04% of them. In this case, all interactions with the servants are scenes where only the servants appear. In none of them do any of the friends or acquaintances of those servants appear. If we confront the group of family-friends-acquaintances with that of servants-friends-acquaintances, our analysis shows that the Earl manifests the core virtue of work in 29.09% of interactions with Group 1 and in 13.04% of those with Group 2 ().

5. Conclusions

When attempting to discover if the paternal identity of Lord Robert, the father in Downton Abbey, is manifested through virtuous actions representative of five core virtues – self-control, joy, work or industriousness, generosity and responsibility – we can conclude that, indeed, this occurs in all the scenes of the first season. In total, the protagonist appears in 80 scenes, and in all of them, he manifests at least one virtuous action, which reinforces our initial hypothesis.

Paternal identity has an ontological dimension that corresponds to the person as such, and a historical dimension in which the person expresses himself in a specific time and space and in relation to others in a specific context. In this series, the virtuous figure of the protagonist reveals who the person of the father is, and how he manifests himself in the family and with all the people with whom he interacts. The virtuous actions of the father demonstrate that he conducts himself according to his role as a father, in order to perfect others: the better the father is, the better he makes himself and others. This attests to the fact that virtue is not attained alone but within the family and its social community.

The core virtue that the father most manifests is self-control, especially through serenity; it appears in 93.75% of the scenes. There is a minimal difference in the frequency of appearance of this virtue depending on with whom the interaction takes place. The Earl manifests self-control in 94.54% of the interactions with his family, friends and acquaintances, and in 92% of the interactions with the servants and their friends or acquaintances.

This minimal difference in the manifestation of virtue occurs again in the case of joy, since the father shows this core virtue in 34.54% of interactions with family, friends and acquaintances and in 32% in those in which he interacts with his servants and their friends or acquaintances. Joy is manifested in 33.75% of the scenes and is fourth in frequency of appearance.

The difference is somewhat greater in the case of generosity. Whereas, with his relatives, friends and acquaintances, Lord Grantham is generous in 63.63% of the interactions, with his servants and their friends or acquaintances he is so in 52% of scenes in which he interacts with them. Generosity, appearing in 60% of the scenes, is the second most manifested core virtue in the figure of the protagonist.

Self-control, joy and generosity are virtues that the protagonist expresses more often with his family than with the servants. However, the Earl manifests another virtue more often in his interactions with his servants and their friends or acquaintances. Such is the case of responsibility. While the protagonist manifests responsibility in 52.72% of the interactions with his family, friends and acquaintances, he does so in 60% of the scenes in which he interacts with his servants and friends or acquaintances of these. Responsibility, manifested in 55% of the scenes, is the third core virtue in frequency of appearance.

Work or industriousness is the least represented virtue: in 23.75% of total interactions. It is presented in 29.09% of the scenes with family, friends and acquaintances, and in 13.04% of those with servants, friends or acquaintances of these. Thus, it is also the virtue most unequally manifested with the interaction groups.

Except for this virtue, where there is a difference of more than double in manifestation percentages if we consider the family/servants interactions, all the others are shown in a homogeneous way in the interactions with both groups. Responsibility even appears more in interactions with servants.

This allows us to conclude that the analyzed character not only shows his identity through virtuous actions that express the core virtues, but also does so in a coherent way, by acting in accordance with all the virtues – and four of the five in similar percentages – in his interactions with both his family circle and that of the servants.

We can affirm that the habits of good choice that Lord Grantham manifests express the notes of his personal identity, and also constitute an example of life in its space-time context, the environment of Downton Abbey in the early twentieth century. In this way, the figure of this protagonist of the series is very attractive because, with his virtuous acts, he transcends not only his family, but also his employees, towards whom he exercises a natural parental concern. This, undoubtedly, is an unprecedented characteristic in paternal representation in a contemporary television series.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elba Díaz-Cerveró

Elba Díaz-Cerveró holds a PhD. in Journalism from the Universidad San Pablo-CEU, Madrid. She has developed extended research around various discourses of the international press and journalistic agendas. She also has headed several research projects endowed by public funding, mostly in the framework of television and new technologies and their different audiences, with special emphasis on children’s audiences. She has published three books, the last of them entitled On the other side of the tunnel. The journalistic coverage of the escape, recapture and extradition of Chapo Guzmán. She has also published more than a dozen scientific articles and chapters in books, and has lectured on these topics at numerous international conferences. Lately, Dr. Díaz-Cerveró became lecturer and researcher at the School of Communications, Universidad Panamericana, Campus Guadalajara, as well as active member (Level 1) of the National System of Researchers (SNI) at CONACYT, Mexico.

Rafael Hurtado

Rafael Hurtado holds a Phd in Government and Culture of Organizations from the Instituto Empresa y Humanismo, Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona. He is an active member of various research projects around marriage and family studies, such as Observatorio Internacional de la Familia (UNAM), Family and Media (PUSC) and The International Organization for the Family (IOF). He is author and co-author of six books, and various academic papers and chapters. He is currently a permanent lecturer and researcher at the Departamento de Humanidades, Universidad Panamericana, Campus Guadalajara.

María G. Crespo

María G. Crespo holds a PhD. in both Theology and Education from the University of Navarra, Pamplona. She is currently a permanent lecturer at the Faculty of Communications and Enterprise at the Universidad de Piura, Perú.

Notes

1 From an online dictionary definition of the Spanish phrase for Self-control, Dominio de sí. http://diccionario.sensagent.com/dominio+de+s%C3%AD+mismo/es-es/

2 From an online dictionary definition of the Spanish word for Balance, Equilibrio. http://definicion.de/equilibrio/#ixzz3bk5p6DUj

3 From an online dictionary definition of the Spanish word for Peace, Paz. http://definicion.de/paz/#ixzz3bk9IkdyZ

4 From an online dictionary definition of the Spanish word for Coherence, Coherencia. http://definicion.de/coherencia/#ixzz3bq981ErL

References

- Abbott, P. 1981. The Family on Trial: Special Relationships in Modern Political Thought. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Aguilar Rocha, S. 2007. Aparte Rei. Revista de Filosofía. Accessed 7 July 2020. http://serbal.pntic.mec.es/∼cmunoz11/aguilar49.pdf

- Alvira, R. 2000. El lugar al que se vuelve. Reflexiones sobre la familia. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Alvira, R. 2020. “Lo común y el habitar humano.” In De la familia a la comunidad. Un estudio interdisciplinario, edited by R. Athié and R. Hurtado, 35–50. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Andrews, K., and R. Hurtado. 2020. “Pitirim Sorokin on Marriage. Family and Culture.” The Chesterton Review XLVI (1 & 2): 127–139.

- Arendt, H. 2005. La condición humana. Barcelona: Paidós.

- Assirio, J. 2013. “La dualidad filiación-paternidad: Estudio según la antropología trascendental de Leonardo Polo.” Unpublished Masters Thesis. Universidad de Navarra/Universidad Austral.

- Assirio, J. 2015. “La figura del padre en Downton Abbey.” In La figura del padre nella serialitá televisiva, edited by E. Fuster, 151–159. Roma: EDUSC.

- Athié, R., and R. Hurtado. 2020. De la familia a la comunidad: un estudio interdisciplinario. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Baena, R., and C. Byker. 2015. “Dialects of Nostalgia: Downton Abbey and English Identity.” National Identities 17 (3): 259–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2014.942262.

- Benavente, J. 2003. “Sobre el esfuerzo como virtud.” Acontecimiento 68: 19–20.

- Carlson, A., and R. Hurtado. 2019. “Familia, Hogar y Libertad: Reflexiones Sobre la familia natural y la economía doméstica.” The Chesterton Review VIII (1): 79–95.

- Corominas, F., and J. Alcázar. 2014. Virtudes Humanas (6th ed.). Madrid: Palabra.

- Crespo, M. 2004. El perdón: una investigación filosófica. Madrid: Encuentro.

- Del Río, P., A. Álvarez, and M. Del Río. 2004. Pigmalión: Informe sobre el impacto de la televisión en la infancia. Madrid: Fundación Infancia y Aprendizaje.

- Delors, J. 2013. “Los cuatro pilares de la educación, Informe Para la Unesco sobre Educación Superior.” Revista Galileo 23: 103–110.

- Esquire 2017. “Downton Abbey: la clave de su éxito”. Esquire. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.esquirelat.com/entretenimiento/downton-abbey-la-clave-de-su-exito

- Fernández Aguinaco, V. 2013. “La familia bien, gracias.” In Revista Crítica. Accessed 7 July 2020. http://www.revista-critica.com/la-revista/monografico/reportajes/125-la-familia-bien-gracias

- Field, S. 2005. Screenplay: The foundations of screenwriting. New York: Delta.

- Fuster, E., ed. 2015. La figura del padre nella serialitá televisiva. Roma: EDUSC.

- Gomá, H. 2013. “Gratitud y agradecimiento.” A post on the website of Herminia Gomà. Accessed 7 July 2020. http://www.coachingparadirectivos.com/2013/01/gratitud-y-agradecimiento/

- González Gaitano, N. 2012. “L’avanguardia cinematografica in cerca della paternità perduta.” Website of Family and Media. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.familyandmedia.eu/cinema-e-tv/lavanguardia-cinematografica-in-cerca-della-paternita-perduta-2/

- Goode, W. J. 1963. World Revolution and Family Patterns. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe.

- Green, T. H. 1967. Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Hurtado, R. 2014. Reflexiones sobre el trabajo en el hogar y la vida familiar. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Hurtado, R. 2011. La paternidad en el pensamiento de Karol Wojtyla. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Hurtado, R., and F. Galindo. 2019. A Stand for the Home. Reflections on the Natural Family and Domestic Life. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Innerarity, D. 1993. “Convivir con la inidentidad.” Anuario Filosófico 26 (2): 361–374.

- Isaacs, D. 2003. La Educación de las Virtudes Humanas y su evaluación. México: Minos.

- Locke, J. 1965. Two Treatises on Government. New York: Mentor Books.

- MacIntyre, A. 1981. After Virtue. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Malo, A. 2015. “Il crepuscolo della paternità-maternità.” On the website of Family and Media. Accessed 03 January 2021. https://www.familyandmedia.eu/non-categorizzato/il-crepuscolo-della-paternita-maternita/

- Marías, J. 1973. Antropología metafísica. Madrid: Revista de Occidente.

- Martínez Priego, Consuelo, María Elena Anaya Hamue, and Daniela Salgado. 2014. “Desarrollo de la personalidad y virtudes sociales: relaciones en el contexto educativo familiar.” Educación y Educadores 17 (3): 447–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2014.17.3.3.

- Mill, J. S. 1869 [2008]. The Subjection of Women. Accessed on Project Gutenberg website, 21 July 2020. gutenberg.org/files/27083/27083-h/27083-h.htm.

- Millán, E., and C. Martínez Priego. 2014. “Dimensiones de la identidad paterna. Aproximación del pensamiento filosófico de Julián Marías.” In Julián Marías. Persona y Reconocimiento, edited by R. Sebastián Solanes, 75–85. Madrid: Editorial Académica Española.

- Naval, C. 1997. “La identidad personal en A. MacIntyre y Ch. Taylor. El primado de la persona en la moral contemporánea.” In Actas del XVII Simposio Internacional de Teología de la Universidad de Navarra, edited by A. Sarmiento, 761–778. Pamplona: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra.

- Parsons, T. 1951. The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

- Polaino-Lorente, A. 1995. “El hombre como padre.” In Metafísica de la Familia, edited by J. Cruz Cruz, 295–316. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Polo, L. 1995. “El hombre como hijo.” In Metafísica de la Familia, edited by J. Cruz Cruz, 317–325. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Polo, L. 1999. La persona humana y su crecimiento. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Porto Pedrosa, L. 2013. “El discurso infantil sobre valores y emociones a partir tres muertes clave en los relatos audiovisuales.” In Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación 4 (2): 5–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2013.4.2.12.

- Rawls, J. 1971. A Theory of Justice, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ricoeur, P. 2006. Sí mismo como otro. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

- Rodríguez Luño, A. 2006. Ética General. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Samaniego, M., M. Pascual, and S. Navarro. 2007. “La televisión y el desarrollo de valores.” In Revista de educación 342: 307–328.

- Sánchez Burdiel, A. 2014. “La ficción televisiva de época e histórica: un análisis comparado sobre las producciones televisivas de España y Gran Bretaña (2004–2013)." (Unpublished Masters Thesis). Spain: Universidad de Salamanca.

- Sánchez-Escalonilla, A. 2014. Estrategias de guion cinematográfico. El proceso de creación de una historia. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Santamaría, M. 2000. Saber amar con el cuerpo. Ecología sexual. Madrid: Libros MC.

- Sellés, J. 2011. Antropología Para inconformes. Madrid: Rialp.

- Sierra Bravo, R. 1998. Técnicas de investigación social: teoría y ejercicios. Madrid: Paraninfo.

- Soto-Bruna, M. 2002. “La serenidad a la luz de la condición creatural de la persona.” Anuario Filosófico 35: 655–674.

- Spaemann, R. 1998. Ética. Cuestiones fundamentales. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Taylor, C. 2006. Fuentes del yo: la construcción de la identidad moderna. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

- Tomás de Aquino. 2010. Suma Teológica. Madrid: BAC.

- Vázquez, T. 2011. ¿Qué ven los niños en la televisión? Madrid: Universitas.

- von Hildebrand, A. 2019. El privilegio de ser mujer. Pamplona: EUNSA.

- Wojtyla, K. 2008. Amor y responsabilidad. Madrid: Palabra.

- Yenor, S. 2011. Family Politics: The Idea of Marriage in Modern Political Thought, Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

- Yepes, R., and J. Aranguren. 2006. Fundamentos de Antropología. Un ideal de la excelencia humana. Pamplona: EUNSA.