Abstract

The shock associated with the outbreak of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic affected the lives of everyone—and religious communities were no exception. Closed churches, bans on public worship, cancelled events, rapid changes to pastoral modes—many of these stories, quite naturally, captured media interest. This study provides an analysis of the image of Christian churches (and in particular the Catholic Church, which is the largest and most influential) as presented in the media in Central Europe, more specifically, in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Through a content analysis based on the concepts of frames and topoi, the study focuses on how the media presented the activities of the churches and the relation between church and government authorities during the pandemic. Based on a sample of 491 media texts published over the period of five months (February–June 2020) in four mainstream secular print/online media, our conclusions point to a predominantly positive image of Christian churches in the media—with the churches being perceived as cooperative, creative, and responsible, pursuing the common good and offering a prophetic interpretation of a difficult situation. On the other hand, fanaticism, fundamentalism, and non-cooperation were presented by the Slovak and Czech media as phenomena more frequently happening in other countries.

1. Introduction and state of the art

The roles, challenges, and activities of churches during the pandemic over the past year have captured the attention of media and scholars alike. This study focuses on how media perceived the interrelations between the pandemic and churches from two key perspectives: (1) which religious activities captured media attention; and (2) how the media presented the relationship between church and government authorities. The research was conducted in the context of two Central European countries: Slovakia and the Czech Republic. The selection of these two countries was by no means accidental: the Czech Republic and Slovakia used to form one state (Czechoslovakia) for a period of 70 years (1918 − 1939 and 1945 − 1993). As part of a civilized divorce, the country split in 1993 and became a paragon of peaceful dissolution. The split has gone down to the history of Europe as the ‘velvet divorce’. Both countries have a much different relationship to religion: whereas Slovakia is one of the most Christian countries in Europe,Footnote1 the Czech Republic is officially labelled as ‘the most atheist’ country in Europe.Footnote2

Previous research into the relationship between religion and the Covid-19 pandemic has focused on several categories of topics. For the most part, scholars explored questions related to mental health and how religious experience and services provided by churches helped people cope with difficulties, stress, or diseases (Modell and Kardia Citation2020; Koenig Citation2020; DeSouza et al. Citation2021). Some scholars also examined the meaning of spirituality in the fight against the pandemic and pointed to heroic stories of both clerics and lay believers who did not hesitate to help out in hospitals (Chirico and Nucera Citation2020). Genig (Citation2020) focused on the role of mystery and the differences between a modern and post-modern approach to mystery. He suggests, for instance, that the pandemic provides an opportunity for post-modern doctors of the new millennium to revert to the ancient understanding of humanity, sickness, suffering, and death. A group of Italian scholars led by Molteni conducted a quantitative analysis which suggests that people suffering from Covid-19 were more religious (Molteni et al. Citation2021)—as reflected in their prayers or participation in masses—and that dramatic events, such as the outbreak of a pandemic may lead to a temporary religious revival despite a broader secularization trend. The research of Pirutinsky, Cherniak, and Rosmarin (Citation2020) which focused on the Orthodox Jewish community in the United States confirmed that faith can enhance people’s personal resilience, especially during crises. ‘Positive religious coping, intrinsic religiosity and trust in God strongly correlated with less stress and more positive impact, while negative religious coping and mistrust in God correlated with the inverse’ (Pirutinsky, Cherniak, and Rosmarin Citation2020, 2288).

With respect to the positive influence of religion and church activities on mental health, there is a consensus among scholars that cooperation between religious and other social authorities is plausible. Hong and Handal (Citation2020), for instance, focused on three institutions: religion, science, and government. Over the past centuries, all three institutions have helped the population overcome their anxieties and perils of events similar to the current pandemic, and acted in the interest of the common good. Therefore, it is necessary to combine the instruments used by all three of them. Moreover, partnerships of public and religious institutions are supported by Weinberger-Litman et al. (Citation2020). His team concludes that community organisations enjoy much greater trust with respect to Covid-19 compared to any other institutions, such as government authorities, state-level, federal, international institutions, or, for that matter, the media. The notion of the common good is also the leitmotif in VanderWeele (Citation2020), who highlights the contrast between one’s own spiritual benefit associated with attendance of public worship and the love of neighbour expressed by refraining from doing so. He suggests that although the ban on public worship interferes with the spiritual benefits of a believer, the love of neighbour encourages him or her to surrender public worship and thus help protect public health. ‘While none of increased personal and family prayer and devotion, video-streaming of services, and online prayer and discussion meetings fully compensates for the loss of in-person meetings, the sacrifice entailed may itself be seen as a means to greater love of God and love of neighbor’ (VanderWeele Citation2020, 2196).

The second category of research efforts represents projects focused on modifications and new approaches introduced by churches into their rites and spiritual service during the pandemic. Bryson, Andres, and Davies (Citation2020) combined the methods of human geography and theology to conclude that the rapid shift of churches to providing online public worship services and its presence in the virtual world has blurred the dividing line between sacred and secular spaces. Neologisms, such as ‘intersacred space’ or ‘temporary sacred space’ were introduced to describe the new phenomena. Bawidamann, Peter, and Walthert (Citation2021) examined the authority of religious leaders in introducing changes. A team of Polish scholars (Przywara et al. Citation2021) offer a detailed analysis of the quality and quantity of online masses in Poland with respect to multiple factors including the size of the parishes, diocese, or monastic type of parish, or the support of local bishops. Kim (Citation2020) examines the transformation of Christian worship services through the prism of the principles of liturgy inspired by the Pauline theological concepts. He concludes that the transformation to ‘contactless’ worship services has already taken place without being subject to the scrutiny of public debate. He also recommends that we do not judge the new approaches as good or bad, but rather look at the essence of the Gospel message and ensure it is not misrepresented along the way.

Other scholars focused their research on specific activities of churches during the pandemic, such as telephone helplines or other practical support inspired by the Gospel for the benefit of ordinary people (Conteh Citation2020; Galiatsatos et al. Citation2020). Some of the research focused on the challenges faced by churches in the post-corona age. Scholars have suggested that the pandemic uncovered a deeper crisis for churches, which requires a profound transformation. Hwang suggests that the renewal of missional ecclesiology as an alternative ecclesiology is the way forward that can overcome the limitations of traditional churches (Hwang Citation2020, 430). Levin (Citation2020) understands the pandemic as a test of institutional religion. Hill, Gonzalez, and Burdette (Citation2020) also provide some interesting insights as they examine the relationship between the degree of religiousness in individual US states and the population’s mobility during the pandemic. In-depth qualitative research into the same subject was conducted by Thorndahl and Frandsen (Citation2021). Their work emphasized strong, emotionally charged debate and drew attention to the radical invasion of the coronavirus pandemic into the social order and people’s lives.

The question of possible infringement of religious freedom was discussed by Shimanskaya (Citation2020). She examined the question to what extent the restrictive measures of governments were reasonable and justified. She also pointed to the difference between the first and second wave of the pandemic: whereas during the first wave of the pandemic both the churches and believers accepted the ban on public worship as an inevitable measure and were cooperative, church officials in the second wave began to criticize national governments for discrimination against believers. Therefore, Shimanskaya recommends changes to the European legislation on freedom of religion with respect to public safety as a basis for sustainable economic, political, and cultural development in Europe.

Previous notable research efforts into the subject also include inquiries into the media image of Christian churches in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, or more specifically, the question of how various religious events are presented in the media (Gazda Citation2009; Psárová Citation2020a); some scholars have highlighted the superficial approach of the media to covering religious events and their tendency to focus on oddities or other irrelevant aspects and their failure to appreciate the key spiritual messages of the covered religious events (Gazda Citation2017). Some scholars have also pointed to a certain tension between the media and church communicators (Švejda Citation2010; Rončáková Citation2019), or a significant tendency of media to emphasize conflict (Zavadilová Citation2020). Some scholars, especially in the Czech Republic, have explicitly pointed to some churches’ tarnished reputations and long-lasting negative media image (Hejlová Citation2020).

2. Methodology

The key question of our research was how mainstream secular media in Slovakia and the Czech RepublicFootnote3 covered topics related to churches during the pandemic. With respect to the above, the following research hypothesis can be formulated: media coverage of religious and church-related topics during the pandemic has remained, for the most part, superficial and hostile.

The research question formulated above was addressed through quantitative and qualitative content analysis using the method of frames and topoi. The method of content analysis is interdisciplinary and, in addition to the analysis of media content, it is used in the whole spectrum of scientific disciplines from pedagogical sciences through psychology, marketing to mass media communication (Neuendorf Citation2002). This method was first applied by Lasswell in 1927 to study propaganda, and subsequently became very popular in the research of film content and later the mass media, with researchers focusing on violence, racism, and the status of women (Shoemaker and Reese Citation1996). Neuendorf distinguishes four main tasks of content analysis: descriptive, psychometric, deductive, and predictive (Neuendorf Citation2002, 53). We applied descriptive content analysis. It is important to distinguish between quantitative, qualitative, and combined content analysis. Qualitative analysis better covers factors that affect the audience and their beliefs or behaviour (Macnamara Citation2011, 2). In the case of media texts, it makes it possible to better understand their deeper meaning and possible interpretation by the recipients.

The theory of framing has been continuously evolving since the 1970s. It is an integral part of the study of cultural and social discourse. As Cappella and Jamieson (Citation1997) explain, frameworks enliven the rules and concepts present in culture, creating the context. McQuail points out that in media practice, frames are necessary to convert information into a meaningful form in a short time (Citation2009). Pan and Kosicki (Citation1993) identify the frame with the central motif of the text (theme) while making a special distinction between the theme and topic. This distinction is an important one because sometimes ‘frames’ or ‘themes’ and ‘topics’ may appear very similar categories. Pan and Kosicki however draw a clear distinction between the ‘frame/theme’ which they regard as a dominant aspect of the issue being covered in the text, and the term ‘topic’ which takes on the sense of a leading motif of a specific slice of reality. Kuypers (Citation2006) understands the frame as the ‘central organizing idea’ of a narrative event. Iyengar (Citation1991) distinguished between episodic frames (in the context of an event) and thematic frames (in a more general, abstract context). According to Entman (Citation1993), frames determine aspects of events and phenomena and their interconnection to promote a certain interpretation, evaluation, and/or solution. He explains their functions: defining a problem; interpreting causes; expressing a moral attitude; and promising a solution, remedy, or response. Various factors are involved in creating the frames, such as societal norms and values, organizational pressures and constraints, the influence of interest groups, professional routines and procedures, and the ideological and political orientation of journalists (Môcová Citation2020). Among these influences, some authors include the cultural context of society. For example, Goffman (Citation1974) claims that frames are rooted in cultural reality, and in the case of the dependence of the media frame on culture, it is the so-called cultural resonance.

When evaluating the frames of individual texts we used the predefined frames inspired by previous research of Lewis and Weaver (Citation2015) and Contreras (Citation2007). The Discussion section below provides a detailed analysis of how the selected frames feed into our research. From among the list of frames identified by Lewis and Weaver, we have included the frame of conflict, economic consequences, and human interest. Unlike Contreras, we have opted for a different methodological approach. His ‘frames’, to some extent, overlapped with ours, but also with the categories of topoi. However, on top of the existing categories, we have also created some room to introduce new frames.

Topoi are the underlying argumentation bases or commonly shared convictions. In the theory of rhetoric, these are foundations of arguments denoted by the Latin term loci (comuni), i.e. common places, which stands for the Greek topoi. When investigating topoi we have opted for structuralist-semiotic approach. Structuralists have formulated the following three foundations of their theory: (1) the perceived world can be structured in binary oppositions A/non-A; (2) individually occurring events and phenomena are based on deeply embedded universal rules; (3) these rules and relationships between partial elements can be examined as a compact whole (Gunter Citation2000, 86). This means that two contradicting convictions can be rooted in the same topos (and they often are). Therefore, we are using the notion of ‘contradictory argumentation vectors’ which evolved from an identical point (Psárová Citation2020b; Rončáková Citation2021). At the same time, topoi represent an instrument of rhetorical analysis, as noticed by Norberto González Gaitano, drawing on Cicero’s Orator and Aristotle’s Rhetoric. He defines topoi as the ‘types of arguments used in each argumentation which—in rather technical sense—work as questions which facilitate the search for arguments and counter-arguments’ (González Gaitano Citation2008, 12). The translation of the term topoi as ‘common places’ is from Cicero, who understands them as ‘intuitive places of mind’, that is, generally accepted knowledge, which allows members of a specific social community to understand each other (Cicero Citation1998, 46). Loci in public discourse can be identified with those shared convictions, which are at the ‘root’ of society. In that sense, natural (anthropological) topoi can be discerned from cultural topoi. ‘The topoi offer moral principles that allow one to critically examine and understand the rationale of many newspaper articles. They are present in news and in popular fiction, even though they may not become apparent until society’s moral values change or are brought into discussion’ (González Gaitano Citation2009).

When evaluating the topoi in the texts included in our sample, we have based our categories on the predefined categories taken from González Gaitano (Citation2009), but in addition, we have also introduced new categories. Although the categories of topoi and frames originated for the most part from previous research into the subject, to some extent, they have also crystallized during the research—something which is quite typical for qualitative content analysis. As for the newly introduced topoi and frames (in addition to those already formulated in previous studies), these were based on the specifics of the subject matter of research by identifying the dominant aspect(s) of the issue being covered in the texts (in the case of frames)—and by identifying the shared assessments/value judgments about such aspect(s) or parts of them (in the case of topoi). Since the sample was not coded by a team of researchers but only by one author, the intercoder reliability test was not required.

The sample included a proportionate number of Czech and Slovak texts. The aim of focusing on the Czech and Slovak media was to obtain a typical Central/East European sample, proportionately representing the current secular/religious and liberal/conservative tensions. One of the advantages of such an approach is that for Slovaks, the Czech language is as understandable as their mother tongue, so the author of this research was able to use her competence in coding the local media for both countries. The sample was created from the texts of the four key secular mainstream print/online media, two media for each country were selected: a daily with the highest circulation (SME daily for Slovakia, and Mladá fronta DNES for the Czech Republic); and two most visited news websites (Aktuality.sk for Slovakia and Novinky.cz for the Czech Republic).Footnote4 All four media enjoy a similar reputation of being respected titles (with somewhat tabloid patterns, which are, however, typical for the contemporary press in general; cf. Izrael Citation2009; Osvaldová Citation2016); all of them pursue professional journalism and position themselves as liberal. The texts of both dailies were examined using their web platforms. The sample included texts which contained the following keywords: ‘church’, ‘worship’, ‘priest’, ‘bishop’; and which covered the relationship between churches and the pandemic in more detail (this means that texts enumerating other restrictions with marginal references to closed or open churches were excluded). The timeframe of the published texts was determined based on the duration of the first wave of the pandemic, i.e. the period of February—June 2020. Hence, we arrived at a sample of 491 texts ().

Table 1. Number of texts.

The recorded identifiers (Scherer Citation2004) included the title of the news source, domestic/foreign nature of the text, and the publishing date. The ratio between domestic and foreign texts—in terms of the origin of the story that was covered—was ∼3:2 ().

Table 2. Distribution of texts covering domestic vs. foreign stories.

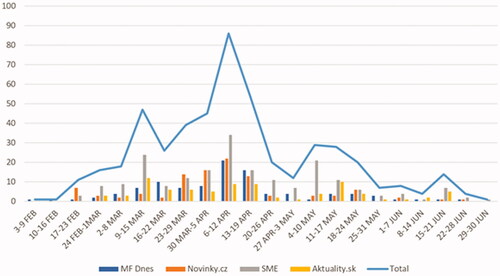

The publishing dates of individual texts have reflected the development of the pandemic and the related restrictions. In Slovakia, the ban on public worship was lifted on 10 March 2020, and later reimposed (to some extent) starting 6 May 2020. In the Czech Republic, public worship was banned from 15 March 2020 until 24 April 2020. From then on, the limit on the number of participants at worship services gradually increased from 15 to 500 believers. During the summer, services were allowed with minimum limitations ().

The curve reflects the following three peaks: first, closing of churches in March; second, Easter season during April (Easter Sunday falling on 12 April 2020); and third, reopening of churches in May. Whereas Slovak media gave more coverage to the closing and opening of churches, Czech media provided more extensive coverage through church-related stories in the period around Easter.

3. Findings

3.1. Frames

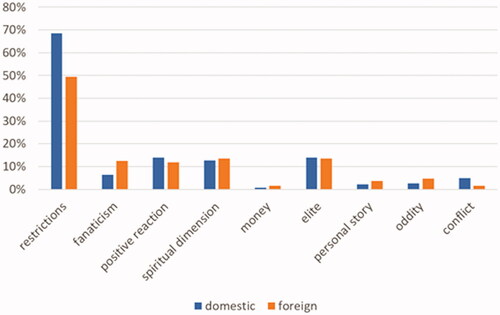

Nine frames were identified in the texts subject to review (). Although one text may have included several frames, such cases were quite rare (coefficientFootnote5 of 1.21 frames per text).

Table 3. Frames.

The relation between the variables in the crosstab was examined through the chi-squared test.Footnote6 The resulting p-value of 0.0016 was lower than the standard significance level of 0.05. This proves that the frames and media were mutually dependent—i.e. individual media have framed the subject matter of the research in a significantly different way.

Clearly, the most frequent frame was the restrictions frame (two-thirds of all occurrences). This frame included detailed information about the opening and closing of churches, limits on the number of believers that were allowed to gather, cancellations of planned feasts and pilgrimages, as well as reports on the impact of those restrictions on the churches.

The fanaticism frame pointed to the irresponsible behaviour of churches and individuals, who decided to organise mass events despite the risks of spreading the virus, or texts in which the authors challenged narrow-minded religious behaviour. Within the Czech and Slovak context, stories included mainly unlawful masses organised privately or other activities potentially harmful to public health from abroad (the Orthodox Church in Russia, Ukraine, Romania, and Georgia; disobedient protestant pastors in the so-called Bible Belt in the US; or Polish Catholic priests). The Shincheonji sect in South Korea was also covered several times, including the news of the super-spreader nicknamed ‘crazy auntie’.

As for the category captioned as a positive response, we have included texts framed to convey a positive message that the activities of churches are beneficial for society in view of the outbreak of the pandemic. Reporters highlighted the churches’ creativity and their flexible switch to the online environment, charity events, establishment of helplines, the personal sacrifice of priests helping out in hospitals, or the donation of 200,000 euros by the Slovak bishops to the Catholic Church in Italy, etc. In Slovakia and the Czech Republic, reporters also noticed the blessing of the country by Pope Francis while flying over Slovakia and the exposition of relics of saints to protect against plague as well as stories about the Shroud of Turin. Media have also brought the story from Berlin where a local pastor offered the premises of a Lutheran church to Muslims during Ramadan because their mosque could not accommodate the crowd, in an effort to help Muslims comply with the adopted social distancing restrictions.

The frame of spiritual dimension included texts where reporters approached religious authorities for consolation and encouragement during difficult times. This category included public speeches of various religious leaders, especially the Pope, and interviews with bishops and priests in those regions. Questions sought to understand the deeper meaning of this difficult period, as media asked for advice on how to use this period wisely and find spiritual fulfillment.

The frame of money pointed to the churches’ funding constraints; however, this frame was quite rare.

The frame of elite included texts in which the presence of a well-known figure was dominant. This pertained mainly to Pope Francis; a minority of cases included various local bishops, or heads of local churches in other countries (such as Kiev Pechersk Lavra Metropolitan Pavel, Russian Patriarch Kirill, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby).

Quite surprisingly, the otherwise popular media frame of personal story has been muted during the pandemic. Stories included infected and recovered priests and believers. The story of Giuseppe Berardelli stood out and was featured several times in the texts from our sample. The Italian priest decided to give his ventilator, purchased for him by his parishioners, to a younger patient. The priest later died of Covid-19.

The frame of oddity included reports of various creative ideas including some failures. Most of them referred to the Shincheonji sect. Most of the texts did not frame ‘crazy auntie’ as a fanatic but pointed to the obscure nature of the sect as such. One could also find some funny stories about an Italian priest who accidentally activated filters while recording the mass (the video went viral); an Anglican priest whose jumper caught on fire after leaning too close to a candle; or an Argentinian pastor who decided to dress as a waiter and furnish his church as a restaurant (at a time when the restaurants were open and churches closed); or priests who blessed cars using a water gun, or charlatan televangelist Kenneth Copeland ‘healing’ via TV screen.

Another typical media frame related to churches and Covid-19 was conflict. This frame usually included conflicts between church officials and government authorities, for example over illegal worship services. In Slovakia, the narrative of a conflict between churches and shops was quite frequent, especially when the government decided to close the shopping malls on Sundays for disinfection purposes—a step which infuriated Slovak liberals.

As for the focus on domestic and foreign stories of the sampled texts (), it can be concluded that domestic affairs prevailed over foreign affairs within the frames of ‘measure’ and ‘conflict’; while foreign stories prevailed within the frames of fanaticism and oddity.

When comparing the Slovak and Czech texts () the frame of ‘elite’ and also to some extent the frame of ‘fanaticism’ and ‘positive response’ was prevalent. In Slovakia, the prevailing frame was that of ‘conflict’.

3.2. Activities of churches

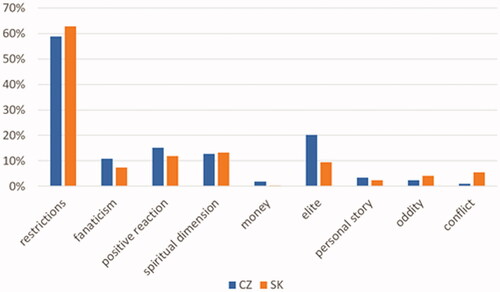

Within the context of frames, we have also examined which particular activities of churches have been covered in the reviewed media texts; thus, we arrived at six categories (). Here, we have taken the liberty to assign several activities to a single text, but only a tiny fraction of texts corresponded to more than one activity (coefficient of 1.04 activities per text).

Table 4. Activities.

The relation between the variables in the crosstab was examined through the chi-squared test. The resulting p-value of 0.3 was higher than the standard significance level of 0.05. This means that the activities and media were not mutually dependent—i.e. the proportions of the coverage of the types of activities by individual media were very similar.

One-third of the texts did not refer to any church activities. The remaining texts mostly referred to the activity of service, which also included to great extent information regarding online masses along with information on the possibility of arranging weddings, baptism services, or funerals; processions, pilgrimages, blessing of meals, adorations, first communions, etc. Interestingly, as many as 19% of texts within this category included negative reports about organising worship services ‘at any price’, all sorts of illegal gatherings, and disobedient pastors and the like.

Surprisingly, the share of charity activities performed by churches was relatively small. These would include stories of priests serving at hospitals, churches helping distribute food to the needy, engagement in educational activities for socially disadvantaged children, or the supplying of protective shields by the Church of the Brethren.

The anticipated media coverage of political activities of churches has not materialised. The only text within this category pointed to a strong political agenda of the churches, which according to the author is contrary to liberal and social democracy.

On the other hand, the evangelization activities of churches were strongly represented. These included Pope Francis’ addresses, all sorts of messages, prayers, Eucharistic blessings, speeches of the representatives of churches, and social activities carrying a strong spiritual message.

Within the category of psychology, we have recorded several activities related to psychological or therapeutical help, e.g. helplines established by religious orders or by bishoprics, a service provided by believers in retirement homes, or volunteers making themselves available for conversations in geriatric departments.

Within the category of culture, we have included the cultural activities of churches and believers, such as concerts, visual art installations, or exhibitions, e.g. an exhibition of folk customs organized to help people flourish during the pandemic.

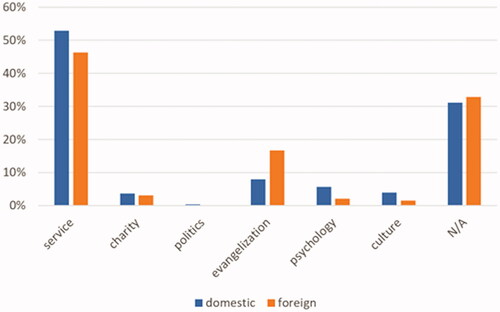

Comparison of domestic and foreign stories () points to a disproportion within the category of evangelization due to the Pope’s messages, which increased the share of foreign reports.

Figure 4. Distribution of activities by the origin of stories—domestic vs. foreign. Source: Own elaboration.

No significant disproportion was observed in terms of activities between the Czech and Slovak texts with respect to their origin ().

3.3. Relationship between church and government authorities

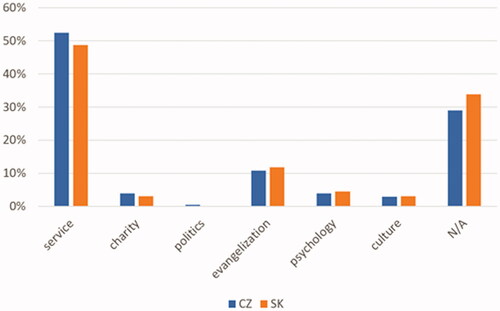

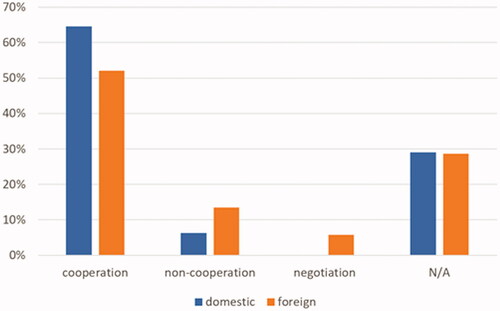

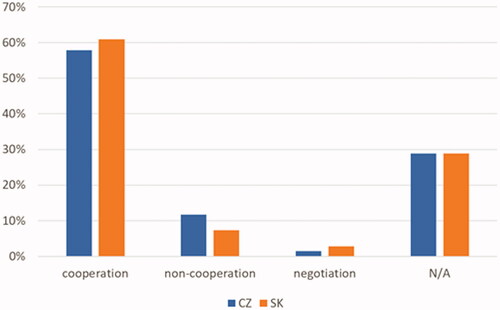

The relationship between church and government authorities was analysed based on their perceived ability to cooperate and work together to tackle the virus; three categories were identified (). In this case, one text was assigned to one category only.

Table 5. Cooperation.

The relation between the variables in the crosstab was examined through the chi-squared test. The resulting p-value of 0.0017 was lower than the standard significance level of 0.05. This means that the presented church-government relationship and the media were mutually dependent—i.e. individual media have presented the church-government relationship in a significantly different way.

Texts in which this relationship was irrelevant represented less than one-third of the sample. These were texts in which the churches were presented as passive, but more often, texts in which the churches performed their own independent activities beyond the standard framework of cooperation with government authorities.

In our Slovak and Czech sample, cooperation between the religious and secular authorities was dominant. For a part of texts, the cooperation was present implicitly—through the obedience of churches and their subordination to the restrictions, or active participation in implementing those restrictions. Many of the texts mentioned the direct engagement of church officials in favour of those restrictions. In the Slovak media, for instance, the adopted restrictions were explicitly supported and explained by the Archbishop Metropolitan, Stanislav Zvolenský, or the spokesperson of the Slovak Bishops’ Conference, Martin Kramara. Other bishops or priests followed suit and provided arguments in favour of introducing restrictions, called for their acceptance, and patience on the part of believers. We have recorded several reports about bishops banning traditional pilgrimages and adopting extra measures to ensure restrictions would not be ignored by overly active believers. Many reports about illegal participation of believers in masses were presented in the same light: for instance, they described how the superiors instructed their subordinate priests and how the problem was fixed, or how the church staff took the initiative to steer believers outside of the church and instructed them to comply with the restrictions. This category also included a report covering Pope Francis, who rebuked conservative priests who demanded public masses during the first wave of the pandemic. The Pope called them ‘unmatured’.

The category of non-cooperation included reports framed mostly as ‘fanaticism’. These included illegal worship services, disobedient parish priests and protestant pastors, or discussed the initial reluctance of the Orthodox church in various parts of Central and Eastern Europe to comply with the introduced restrictions.

The category of negotiation included texts pertaining to churches’ efforts to put on some political pressure to renew public worship (e.g. in Italy or Romania) along with litigations and court rulings on the ban on public worship services (France and Germany).

The comparison between church and secular authorities from the perspective of domestic and foreign origin of those reports () shows that the frame of ‘non-cooperation’ was more frequent in foreign reports. The ‘negotiation’ frame was present only in reports covering stories from other countries.

Differences between the Czech and Slovak texts () were insignificant; non-cooperation was slightly higher in the Czech Republic.

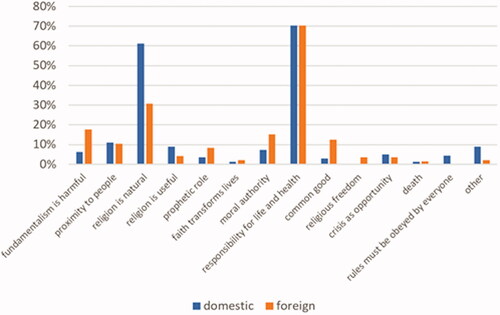

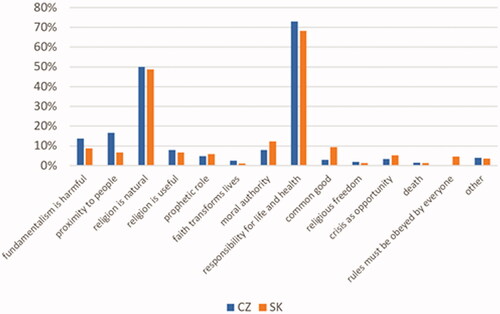

3.4. Topoi

For each text, we have also determined its topos—the underlying basis for argumentation generally shared by society. Within the given topical context, we have identified 13 topoi plus several minority topoi as part of the ‘other’ category (). Quite often, the texts included several topoi simultaneously, and it was difficult or even impossible to identify a ‘dominant’ topos. This is true for more extensive texts with several motifs but also shorter ones, which often refer to both responsibilities for health and natural place of religion on human life. Hence, when classifying the texts into categories we have also allowed the use of several categories simultaneously (coefficient of 1.86 topoi per text).

Table 6. Topoi.

The relation between the variables in the crosstab was examined through the chi-squared test. The resulting p-value of 0.0127 is lower than the standard significance level of 0.05. This means that the topoi and media are mutually dependent—i.e. individual media have based their media coverage on significantly different argumentation bases.

Clearly, the most frequent topos was responsibility for health and human life, which very often overlapped with other topoi, mostly with the topos that religion is natural. These two topoi were present in general information texts, especially with respect to restrictions. The topos of ‘protecting life and health’ was dominant in texts criticising failure or reluctance to comply with the restrictions; authors pointed to churches as a source of epidemiological risk and called for the protection of the health of threatened groups; they also pointed to examples from past epidemics during which churches had to be closed. The topos of ‘religion is natural’ is based on a shared conviction that religion is natural for man. This common place is often associated with the presence of religious rites and symbolic acts as well as their spontaneous media presentation (González Gaitano Citation2009). In our case, it was reflected in reports covering the restrictions relevant for churches, enumeration of online alternatives to worship services (e.g. the Czech daily Mladá fronta DNES organised an online mass for their readers), or information on the nature and meaning of the associated rites performed in a limited scope during Easter period. Media were also publishing information on how to initiate church weddings, funerals, baptism services in times of pandemic; Mladá fronta DNES, for instance, quoted the Mayor of Nový Bor, a village in the Czech Republic, who recommended praying to Saint Rosalie for healing from the plague.

The topos of harmful fundamentalism we have identified mainly in the texts related to the frame of ‘fanaticism’, but also texts reflecting on the non-cooperation of churches—i.e. various breaches of the restrictions in place, pastors, and Orthodox priests rebelling. However, there were also instances of texts expressing the fears about churches, in which liberals presented Christianity as an adversary to democracy and human rights.

The shared conviction of a ‘true religion’ and true pastors who are close to the people was also referred to in the research of González Gaitano (Citation2009). In our sample, media reflected upon and praised various creative and ingenious activities through which churches attempted to stay close to their believers, bringing positive reports about priests who did not hesitate to help out in the hospitals. The Czech media, for instance, published several reports about bishop Tomáš Holub, who was regularly available for people via a telephone line; in Slovakia, the SME daily quoted the Mayor of Rudinská, a small village in Slovakia, saying that the local priest Jozef Bagin was ‘150% available to people’. The same daily opted for a headline ‘A Priest Goes to People’ in an article about the blessing of Easter meals from a horse carriage in the village of Lesnica. This category also included foreign reports about Pope Francis’ calls for prayers for the employees of funeral homes, health care workers, etc. or a report of the Archbishop of Canterbury who made undercover visits to minister to patients in a local hospital.

According to González Gaitano (Citation2009) the topos that religion is useful for society include a conviction that religion ‘helps solve social problems, makes social integration easier, it is not just a standard organisation, religious engagement enhances the fulfillment of civic duties, educates youth, etc.’ Our sample included various charity activities organised by churches, psychological support, and cultural events, but it also included quotes from the US President Donald Trump who declared places of worship ‘essential’ and criticised the preference of some governors for keeping open liquor stores and abortion clinics.

The locus communis of the prophetic role of Christian churches were present in the texts in which media featured bishops and priests expressing their views on what this crisis means, where it can take us and what we can learn from it… Messages of Pope Francis quoted by media offered a similar picture. The Pope gave a special Easter Urbi et orbi blessing which helped expand the spiritual dimension of the debate on the pandemic in both countries. In Slovakia, the activity of the Lutheran bishops also caught media attention, with bishops calling for a free Sunday (with closed shops).

The topos of faith transforms lives was relatively poorly represented. In our sample, this common place was employed by media when covering inspirational stories of lay persons, priests, or monks who set an example for others during the pandemic—along the biblical lines of ‘let your light shine before men’ or ‘no one lights a lamp and puts it under a bowl’. Within our sample, these were mainly texts referring to the Italian priest mentioned above, who gave up his ventilator in favour of another patient, or other heroic acts of priests and lay persons who showed great deeds in caring for the sick.

According to González Gaitano, the topos of moral authority of church officials pertains mainly to the Pope (2009); our sample included many texts featuring the Pope’s messages within this category. Other priests and bishops were also featured during the pandemic and their voice was presented as highly relevant. This topos was partially overlapping with the one of the prophetic roles.

The locus of common good was recorded in texts highlighting the calls of church officials for responsible behaviour and limitation of one’s desires for the sake of the good of others. In the Slovak context, Archbishop Stanislav Zvolenský and his personal messages caught some media attention; for example, he stated that the restrictive measures were very painful and constraining but at the same time acknowledged that they must be followed for the good of the whole society. He also quoted Pope Francis that we are responsible for one another. Media praised the Pope’s cancellation of his trip to East Timor on the grounds of responsibility toward people; and also pointed to the cancellation of big summer pilgrimages in Slovakia with bishops as responsible behaviour. Texts with the opposite argumentation vector were also represented in this category. These included texts criticising irresponsible behaviour on the part of churches and individuals. The media expressed resentment over their recklessness and egoism. When the Orthodox Church refused to introduce the restrictions, the then-prime minister Peter Pellegrini called such behaviour egoistic—a message that caught a lot of media attention.

The topos of religious freedom was quite rare in the Slovak and Czech mainstream secular media; however, it was quite frequent in church and conservative media (Rončáková Citation2021). Secular media brought reports in that respect solely from abroad: they covered decisions of the courts in Germany or France, arguments put forward in the USA based on the First Amendment, or stories, such as the activity already mentioned above of the Argentinian priest dressed as a waiter.

The topos of crisis as an opportunity is based on a conviction that a difficult life situation has the potential to help us (re)discover what is essential, refocus our priorities, and deepen our own spirituality. From the theological perspective, this entails strong faith in God, in His goodness and love as presented in the Scripture, especially in the story of Job. In Slovakia, this echoes a popular phrase ‘what does not kill you makes you stronger’. In that sense, priests or bishops often encouraged people to stop for a while, take a break, rethink, reassess or reinterpret one’s life, make it more focused and discover new depths.

Death represents a general human phenomenon. In every culture, the awe before death is present and associated with fear and questions about the life ‘after’. Compared to the massive number of deaths during the pandemic, quite surprisingly, this topos was represented quite poorly. Sometimes interviewers asked questions on the meaning of death in interviews with priests; the SME daily covered the subject during Easter in an interview with the Greek Catholic Archbishop, Cyril Vasiľ: ‘One can think of death as a temporary winner of moral and physical evil, but it is never our final station. Death will never be the ultimate winner. We are born for life, we are born for eternity—that is the endless greatness embedded in human life and this entails the courage to take responsibility for the life entrusted to us, and for the way we live it. Each year we celebrate this basic truth which is at the same time the biggest celebration of life—even when faced with all kinds of dangers, threats, and even in the darkest hour of an individual or the whole society’ (Marcinová Citation2021).

Due to the higher-than-expected occurrences of the topos rules must be obeyed equally by everyone this newly introduced locus communis was set aside from the category of ‘other’. This topos occurred exclusively in the Slovak media in texts characterized by contempt of liberals over the preferential treatment of churches at a time when fitness centres, shops, cinemas, and sports arenas were closed. Authors often criticised churches for enjoying an unfair advantage over other institutions.

Within the category ‘other’, the locus of pressure and oppression by churches (N = 3) was based on a notion that churches try to dictate how people should live and that believers impose their convictions on others. To some extent, this topos correlates with the two topoi described by González Gaitano: ‘church is an earthly power’ and ‘democratic administration within the Church is lacking’. Similarly, we have also recorded the topos even a bishop is just a man (N = 3), based on the notion that on a certain level (such as sickness), all human beings are equal. We have also recorded the topos of a connection between beauty and spirit (N = 2), with stories covering strong aesthetic and spiritual experiences. Another quite significant common place present in the Slovak and Czech language environment could be described through the idiom ‘one cannot command the wind and the waves’ (N = 7). The texts in this category were based on the fact that man is powerless against natural forces and at the end of the day, subject to the laws of nature; despite scientific progress, these forces are—and always will be—beyond the control of human beings. Novinky.cz website published an extensive essay written by a Czech political scientist and diplomat Petr Drulák on how the loss of the sense of faith in God has led civilisation to the adoration of substitute idols, most recently Nature, and why this loss is now taking a destructive toll on societies (Drulák Citation2020).

The distribution of domestic and foreign texts () shows the disproportion of the topos of the nature of religion, where the domestic reports prevailed (information about the restrictions and options for church services). The topos of harmful fundamentalism was prevalent within the texts originating abroad (breach of rules); this was also true for texts based on the prophetic role of churches and their moral authority (thanks to the featured messages of Pope Francis).

The distribution of texts between Slovak and Czech environment () points to differences only within the minority categories. Within the Czech environment, the common places of ‘fundamentalism’ and ‘proximity to people’ caught more media attention; in the Slovak environment the topoi of ‘moral authority’ and ‘common good’ prevailed. The topos ‘rules must be obeyed by everyone’ was recorded only in Slovakia.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The analysis set out above sought answers to the question of how the media covered church-related topics during the Covid-19 pandemic in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. This was achieved through four key subject areas in our examination:

frames: how media framed the subject;

the activities of churches: what activities of churches were presented in the media;

the relation between the church and government authorities: how the media presented their cooperation/non-cooperation; and

topoi: what were the underlying shared convictions at the basis of those texts.

To some extent, the identified frames correlated with the list of frames traditionally used in media research (Lewis and Weaver Citation2015): our sample included frames, such as conflict, money (economic consequences), and personal stories (human interest). Other frames (such as attribution of responsibility, morality, character, performance) were not relevant for the purpose of this research. Compared to the frames used by Diego Contreras, who examined the way the secular press presents news about the activities of the Catholic Church (2007), the frames used above were closer to the so-called news values, and did not carry an evaluative charge to such an extent. Therefore, the frames of Contreras sometimes correlated more with our topoi (the Church is the enemy of progress ∼ fundamentalism is wrong; the Church is beneficial for the society ∼ religion is natural for human beings). The best match with Contreras could be found in the notion of the positive response of churches to the pandemic (∼ the Church does good).

The frames inspired by previous research were supplemented by our own efforts relevant to the given context. Hence, for the given context, in addition to the above, we have also included the frames of ‘restrictions’, ‘spiritual dimension’, ‘elite’, and ‘oddity’. The last two can be aligned with classical news values. By far the most frequent frame was the frame of ‘restrictions’ (61%) which included mostly neutral informative texts. Fairly frequent Covid-19-related frames included ‘positive response from churches’ (13%), ‘spiritual dimension’ (13%), and ‘elite’ (14%). On the other hand, in this context, the traditionally strong media frames, such as ‘conflict’ (4%), ‘personal story’ (3%), and ‘money’ (1%) were less frequent. It can be concluded that the media framing toward churches was generally quite positive.

The process of identifying the topoi was inspired by previous research efforts, especially the extensive list of 23 common places presented by González Gaitano (Citation2009) and subsequent research projects (Rončáková Citation2011, Citation2012). The following loci from our list coincided with those identified by González Gaitano:

1. fundamentalism is harmful;

2. religion is natural;

3. religion is useful;

4. churches have a prophetic role;

5. faith changes lives;

6. religious leaders have a moral authority.

In addition, the following categories were identified as useful for the purpose hereof:

7. we must be responsible for life and health;

8. pursuit of common good is laudable;

9. religious freedom is essential;

10. crisis is an opportunity;

11. death has a meaning;

12. rules must be obeyed by everyone;

13. Other.

Within the category captioned ‘other’, the following new topos stood out: ‘we cannot command the wind and the waves’.

In the given pandemic situation the topos of ‘responsibility for lives and health’ (70%) and the topos of ‘religion is natural’ (49%) were dominant, and quite often these two topoi were overlapping. As for other more relevant loci communis, it was mainly the one of ‘proximity of churches to people’ (11%) with texts carrying a positive charge on one hand, and the negatively charged topos of ‘fundamentalism’ (11%) on the other. The common place of ‘moral authority of churches’ was also quite frequent (10%), often associated with the topos of ‘prophetic role of churches’ (5%). Surprisingly, the loci of ‘faith changes lives’ (2%), ‘religious freedom’ (2%), and ‘death’ (1%) were rare despite their strong associations with the reality of the pandemic.

A detailed examination of the presented church activities showed a strong prevalence of texts covering the dimension of churches as spiritual service (50%). From among other categories, the evangelization activities were presented quite frequently (11%), along with surprisingly poor representation of charity activities (3%).

From the perspective of cooperation with secular authorities, the media image of Christian churches in Slovakia and Czech Republic is very positive: as many as 60% of texts pointed to harmony and mutual cooperation, and in 29% of texts, this dimension was not present; hence only 11% of texts have set the relationship between churches and government in a negative or conflicted light.

Despite significant differences between the two countries as described at the beginning, the distinction between Czech and Slovak texts has not materialised into any significant differences in terms of media coverage. In Slovakia, the frame of conflict was more significant, and this was related to the liberal aversion toward open churches at a time when shops and other institutions had to be closed. It can be concluded that ‘atheist’ Czech Republic has shown the same—if not a higher—degree of affinity to Christian churches during the pandemic compared with ‘Christian’ Slovakia (cf. Tkáčová Citation2014, 195, Citation2016, 96).

When looking at the domestic and foreign nature of the texts under review, it was found that the texts covering stories from abroad included to a greater extent the frame of ‘fanaticism’, the topos of ‘fundamentalism’ with references to non-cooperative churches. This means that the Slovak and Czech media perceived these negatives during the pandemic as a foreign phenomenon, rather than a domestic issue. In addition, the common places of ‘moral authority of churches’ and ‘evangelization activity’ were more typical of texts covering foreign affairs, which was related to the coverage of Pope Francis’ messages.

Several connections to previous research efforts can be identified in our findings. The willingness of the media to cover the topic of ‘restrictions’ and ‘church services’ during the pandemic points to the interest of media in specific activities of churches, new approaches, and alternatives, which churches creatively introduced during the pandemic (Conteh Citation2020; Galiatsatos et al. Citation2020; Bawidamann, Peter, and Walthert Citation2021; Przywara et al. Citation2021; Kim Citation2020). The emphasis on useful activities of churches in the field of mental health (Modell and Kardia Citation2020; Koenig Citation2020; DeSouza et al. Citation2021; Pirutinsky, Cherniak, and Rosmarin Citation2020) was reflected in the texts about the ‘positive response of churches’, ‘psychological and therapeutical help’, ‘usefulness of religion’ and ‘proximity of churches to people’. Within our research sample, the media placed a significant focus on the cooperation of churches with the government and other relevant authorities (Hong and Handal Citation2020; Weinberger-Litman et al. Citation2020). The topos of ‘crisis as an opportunity’ touches upon the recent research into the post-pandemic challenges faced by churches (Hwang Citation2020), the idea of the pandemic as a test of institutional religion (Levin Citation2020), as well as the new approaches to intersacred and temporary sacred spaces as examined by Bryson, Andres, and Davies (Citation2020). These concepts point to the idea that the key takeaway from the crisis should include some kind of new opening of churches toward the world, getting some fresh air, leaving behind the walls of temples, and setting out for new missionary activity. Stories about heroic acts of people transformed by faith contain a reference to previous works of the heroism of believers during the pandemic (Chirico and Nucera Citation2020). Our topos of ‘common good’ points to the findings of VanderWeele (Citation2020) on the love of neighbour. Quite surprisingly, the topos of ‘religious freedom’—referred to by Shimanskaya (Citation2020)—was quite rare in our sample, which in the Slovak and Czech context, was more prevalent in the conservative and religious media rather than secular media (Rončáková Citation2021).

The overall look at the presentation of Christian churches in the Slovak and Czech media during the first wave of the pandemic leaves the media recipient with a positive impression. Media perceived churches as cooperating entities showing common responsibility for human lives and public health, actively and creatively helping others, and staying close to human suffering. The more adversarial parts of media coverage (non-cooperation, fanaticism, and fundamentalism) pertained to a great extent to stories or reports from other countries rather than stories covering domestic affairs. In view of the above, the hypothesis that media take a superficial and hostile approach to religious and church topics has not been confirmed.

Although a quantitative comparison of the treatment of Christian churches by the Slovak and Czech media before the pandemic lies outside the scope of our research, this research can serve as a basis for further investigation into the question (or, for that matter, research) as to whether the implications of the pandemic have managed to erode traditional media news values and bring the spiritual dimension and prophetic role of churches into the forefront of the public discourse. Another question raised by this research is whether the pandemic has contributed to the revival of interest in the religious view of life and death—a conclusion that would be quite remarkable especially for a country like the Czech Republic which is traditionally regarded ‘atheist’. Finally, one could also ask—along with Molteni et al. (Citation2021)—to what extent such a pandemic-driven religious revival could be regarded as temporary in the context of broader secularization trends.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Terézia Rončáková

Terézia Rončáková, Ph.D. (born 1980 in Žilina, Slovakia), after finishing her studies in journalism at the Faculty of Arts and Letters, Comenius University in Bratislava (2002), worked as a journalist at the SITA news agency, Katolícke noviny (Catholic News) and Vatican Radio in Rome. At the same time, she defended her dissertation at the Catholic University in Ružomberok (2006). She habilitated at the Faculty of Mass Media Communication at the University of Sts. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava (2012). Her scientific interest focuses on journalistic and religious style and journalistic genre. She works at the Department of Journalism at the Faculty of Arts and Letters of the Catholic University in Ružomberok. She is a member of the Ladislav Hanus Fellowship, the Association of Catholic Journalists Network Slovakia, and the Forum for Public Affairs.

Notes

1 According to the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, the religious composition of population is as follows: Roman Catholic (62.0%), Lutheran (Augsburg Confession) (5.9%), Greek Catholic (3.8%), Reformed Christian (1.8%), other minority churches (2%), unregistered churches (0.5%), no religion (13.4%), not stated (10.6%). Based on the above, some form of Christian creed is professed by 75% of population.

2 According to the Czech Statistical Office, the religious composition of the Czech population is as follows: Roman Catholic (10.4%), Evangelical Church of Czech Brethen (0.5%), Czechoslovak Hussite Church (0.4%), other minority churches (0.4%), stateless “believers” (9.1%), no religion (34.5%), not stated (44.7%). Hence, the share of Christians in the Czech population is one fifth with the highest share of people of ‘no religion’ within Europe.

3 With respect to different backgrounds of the two countries from the perspective of religious studies, our research was limited to Christian churches, specifically the Catholic Church, and, to some extent the Orthodox Church as well as Protestant churches. Texts covering foreign events have sometimes referred to sects. The only reference to Islam was present in the story of a Lutheran pastor in Berlin who offered his church building to Muslims because their mosque could not accommodate the crowd due to pandemic restrictions.

4 Aktuality.sk are available only on the web, Novinky.cz also have a printed version Právo, a daily with the second biggest circulation in the Czech Republic.

5 The coefficient represents the average number of frames per one text (the total number of identified frames divided by the number of texts); the same calculation method also applies to the coefficient calculated for the activities () and topoi ().

6 Obviously, to meet the conditions of the test, only the columns with values higher than five in each cell were tested. This note also pertains to the subsequent chi-squared tests ().

References

- Bawidamann, Loic, Laura Peter, and Rafael Walthert. 2021. “Restricted Religion. Compliance, Vicariousness, and Authority during the Corona Pandemic in Switzerland.” European Societies 23 (sup1): S637–S657. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1833068.

- Bryson, John R., Lauren Andres, and Andrew Davies. 2020. “Covid-19, Virtual Church Services and a New Temporary Geography of Home.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 111 (3): 360–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12436.

- Cappella, Joseph, and Kathleen Jamieson. 1997. The Spiral of Cynicism: The Press and the Public Good. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Chirico, Francesco, and Gabriella Nucera. 2020. “An Italian Experience of Spirituality from the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 2193–2195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01036-1.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1998. L´Oratore. Milano: A. Mondadori.

- Conteh, Prince Sorie. 2020. “The Church in Sierra Leone: Response and Mission during and after Covid-19 Pandemic.” E-Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences 1 (8): 263–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.38159/ehass.2020122.

- Contreras, Diego. 2007. “ʻFraming’ e ʻnews Values’ Nell’informazione Sulla Chiesa Cattolica.” in Direzione Strategica Della Comunicazione Della Chiesa, edited by Juan Manuel Mora, Diego Contreras, and Marc Carroggio, 121–136. Rome: Edusc.

- DeSouza, Flavia, Carmen Black Parker, E. Vanessa Spearman-McCarthy, Gina Newsome Duncan, and Reverend Maria Myers Black. 2021. “Coping with Racism: A Perspective of Covid-19 Church Closures on the Mental Health of African Americans.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8 (1): 7–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00887-4.

- Drulák, Petr. 2020. “Poručíme větru, dešti? [Are We Commanding the Wind and Waves?]” Novinky.cz, March 23. https://www.novinky.cz/kultura/salon/clanek/esej-petra-drulaka-porucime-vetru-desti-40317237

- Entman, Robert. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Galiatsatos, Panagis, Kimberly Monson, MopeninuJesu Oluvinka, DanaRose Negro, Natasha Hughes, Daniella Maydan, Sherita H. Golden, Paula Teague, and W. Daniel Hale. 2020. “Community Calls: Lessons and Insights Gained from a Medical–Religious Community Engagement during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 256–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01057-w.

- Gazda, Imrich. 2009. “Prezentácia Náboženských Udalostí v Médiách [Presentation of Religious Events in the Media].” In Quo Vadis Mass Media, edited by Beata Slobodová and Ján Višňovský, 389–399. Trnava: University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava.

- Gazda, Imrich. 2017. “Aktuálne Otázky Výskumu Vzťahu Médií a Náboženstva v Slovenskom Kontexte [Current Questions about the Research of the Relationship between Media and Religion in the Slovak Context].” Otázky Žurnalistiky 60 (3–4): 67–70.

- Genig, Joshua D. 2020. “A More Excellent Way: Recovering Mystery in COVID Care.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 302–307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01049-w.

- Goffman, Erwing. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- González Gaitano, Norberto. 2008. “Lineamenti Metodologici per l´Esame Della Rappresentazione Delle Radici Della Socialità Che Hanno Origine Nella Famiglia.” In Famiglia e Media. Il Detto e il Non Detto, edited by Norberto González Gaitano, 9–39. Rome: Edusc.

- González Gaitano, Norberto. 2009. “Public and Published Views on the Catholic Church before and after Benedict XVI Trip to the US.” Presented at a Guest Lecture at the Department of Journalism, Faculty of Arts, Catholic University, March 25, 2009.

- Gunter, Barrie. 2000. Media Research Methods. London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi: SAGE.

- Hejlová, Denisa. 2020. “Církevní Public Relations: proč má u Nás Církev Tak Špatnou Pověst? [Church Public Relations: Why Does the Church Have Such a Bad Reputation in Our Country?].” In Obraz Katolické Církve v Českých a Slovenských Médiích v Letech 2015–2018 [The Image of the Catholic Church in the Czech and Slovak Media in the Years 2015–2018], edited by Petra Koudelková, 11–17. Praha: Karolinum.

- Hill, Terence D., Kelsey Gonzalez, and Amy M. Burdette. 2020. “The Blood of Christ Compels Them: State Religiosity and State Population Mobility during the Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 2229–2242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01058-9.

- Hong, Barry A., and Paul J. Handal. 2020. “Science, Religion, Government, and SARS-CoV-2: A Time for Synergy.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 2263–2268. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01047-y.

- Hwang, Byungbae. 2020. “Advent of the Post-Corona Era and Renewal of the Korean Church: From the Perspective of Missional Ecclesiology.” Theology of Mission 60: 430–458. doi:https://doi.org/10.14493/ksoms.2020.4.430.

- Iyengar, Shanto. 1991. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Izrael, Pavel. 2009. “Bulvarizácia a Terminologizácia v Slovenských Mienkotvorných Periodikách [Bulvarization and Terminologization in Slovak Opinion-Forming Periodicals].” In Quo Vadis Mass Media, edited by Beata Slobodová and Ján Višňovský, 401–410. Trnava: University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava.

- Kim, Joohan. 2020. “A Suggestion for Church Worship in the ʻCoronaʻ Era in the Light of Paul’s Worship Planning Principles.” The Bible & Theology 95: 23–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.17156/BT.95.02.

- Koenig, Harold G. 2020. “Maintaining Health and Well-Being by Putting Faith into Action during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 2205–2214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01035-2.

- Kuypers, Jim A. 2006. Bush's War: Media Bias and Justifications for War in a Terrorist Age. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Levin, Jeff. 2020. “The Faith Community and the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak: Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution?” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 215–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01048-x.

- Lewis, Nicky, and Andrew J. Weaver. 2015. “More than a Game: Sports Media Framing Effects on Attitudes, Intentions, and Enjoyment.” Communication & Sport 3 (2): 219–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479513508273.

- Macnamara, Jim. 2011. “Media Content Analysis: Its Uses, Benefits and Best Practice Methodology.” Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal 6 (1): 1–34. http://amecorg.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Media-Content-Analysis-Paper.pdf

- Marcinová, Daniela. 2021. “Archbishop Cyril Vasiľ: Pandémia až brutálne pripomína našu krehkosť. [The Pandemic Reminds us with Brutality How Fragile We Are].” SME, April 5. https://kosice.korzar.sme.sk/c/22368694/arcibiskup-cyril-vasil-pandemia-az-brutalne-pripomina-nasu-krehkost.html

- McQuail, Denis. 2009. Mass Communication Theory: An Introduction. 4th ed. Praha: Portál.

- Môcová, Lenka. 2020. “Mediálny obraz Slovenska v britských denníkoch [Media image of Slovakia in British dailies].” PhD diss., Catholic University in Ružomberok.

- Modell, Stephen M., and Sharon L. R. Kardia. 2020. “Religion as a Health Promoter during the 2019/2020 COVID Outbreak: View from Detroit.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 243–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01052-1.

- Molteni, Francesco, Riccardo Ladini, Ferruccio Biolcati, Antonio M. Chiesi, Giulia Maria Dotti Sani, Simona Guglielmi, Marco Maraffi, Andrea Pedrazzani, Paolo Segatti, and Cristiano Vezzoni. 2021. “Searching for Comfort in Religion: Insecurity and Religious Behaviour during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Italy.” European Societies 23 (sup1): S704–S720. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1836383.

- Neuendorf, Kimberly. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Osvaldová, Barbora, 2016. “Bulvarizace a Etika v Českých Médiích [Tabloidization and Ethics in the Czech Media].” In Co je Bulvár, co je Bulvarizace [What is a Tabloid, What is a Tabloidization], edited by Barbora Osvaldová and Radim Kopáč, 9–14. Praha: Karolinum.

- Pan, Zhongdang, and Gerald Kosicki. 1993. “Framing Analysis: An Approach to News Discourse.” Political Communication 10 (1): 55–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963.

- Pirutinsky, Steven, Aaron D. Cherniak, and David H. Rosmarin. 2020. “Covid-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping among American Orthodox Jews.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 2288–2301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z.

- Przywara, Barbara, Andrzej Adamski, Andrzej Kiciński, Marcin Szewczyk, and Anna Jupowicz-Ginalska. 2021. “Online Live-Stream Broadcasting of the Holy Mass during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Poland as an Example of the Mediatisation of Religion: Empirical Studies in the Field of Mass Media Studies and Pastoral Theology.” Religions 12 (4): 261. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040261.

- Psárová, Miroslava. 2020a. “Obraz Kresťanstva v Spravodajstve Sekulárnych Slovenských Televízií [The Image of Christianity in the News of Secular Slovak Television].” In Obraz Katolické Církve v Českých a Slovenských Médiích v Letech 2015–2018 [The Image of the Catholic Church in the Czech and Slovak Media in the Years 2015–2018], edited by Petra Koudelková, 89–100. Praha: Karolinum.

- Psárová, Miroslava. 2020b. “Spracovanie aktuálnych kultúrno-etických tém v slovenských médiách [Current cultural and ethical topics in the Slovak media].” PhD diss., University of Presov.

- Rončáková, Terézia. 2012. “Mass Media Coverage of Religious Topics: Understanding Topoi in Religious and Media Arguments.” In Christian Churches in Post-Communist Slovakia: Current Challenges and Opportunities, edited by Michal Valčo and Daniel Slivka, 457–484. Salern: Center for Religion and Society, Roanoke College.

- Rončáková, Terézia. 2019. “Sacrum vs. Profanum: Opportunities and Threats in the Church-Media Relationship.” In Multiculturalism through the Lenses of Literary Discourse. Section: Communication, Journalism, Education Sciences, Psychology and Sociology, edited by Iulian Boldea, Cornel Sigmirean, and Dumitru-Mircea Buda, 283–297. Tîrgu Mureş: “Arhipelag XXI” Press.

- Rončáková, Terézia. 2021. “Closed Churches during a Pandemic: Liberal versus Conservative and Christian versus Atheist Argumentation in Media.” Journalism and Media 2 (2): 225–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2020013.

- Rončáková, Terézia. 2011. “Posuny topoi náboženských posolstiev v mediálnom spracovaní. [How the Media Change the Topoi of Religious Messages].” Studia Theologica XIII (2/44): 72–96. https://www.studiatheologica.eu/artkey/sth-201102-0006_POSUNY_TOPOI_NABOZENSKYCH_POSOLSTIEV_V_MEDIALNOM_SPRACOVANI.php

- Scherer, Helmut. 2004. “Introduction to the Method of Content Analysis.” In Analysis of the Content of Media Messages, 29–50. Praha: Karolinum.

- Shimanskaya, Olga. 2020. “Freedom of Religion and Beliefs and Security under the Attack of Covid-19 Pandemic.” Scientific and Analytical Herald of IE RAS 6 (18): 87–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.15211/vestnikieran620208793.

- Shoemaker, Pamela, and Stephen Reese. 1996. Mediating the Message: Theories of Influences on Mass Media Content. White Plains: Longman.

- Švejda, Adam. 2010. “Mediální Obraz České Katolické Církve [Media Image of the Czech Catholic Church].” Master thesis, Charles University in Prague.

- Thorndahl, Kathrine Liedtke, and Lasse Norgaard Frandsen. 2021. “Logged in While Locked down: Exploring the Influence of Digital Technologies in the Time of Corona.” Qualitative Inquiry 27 (7): 870–877. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420960176.

- Tkáčová, Hedviga. 2014. “Media and Religion in Postmodern Culture.” In Kultúra, Religiozita a Spoločnosť: skúmanie Vzájomných Interakcií [Culture, Religiosity and Society: Exploring Interactions], edited by Katarína Valčová, Michal Valčo, Roman Králik, and Martin Štúr, 189–223. Ljubljana: KUD Apokalipsa a CERI-SK.

- Tkáčová, Hedviga. 2016. “New Age: Detabuization of Human Finiteness.” The Role of Religion in the Globalized World, edited by Stanisław Sorys, Daniel Slivka, and Hubert Jurjewicz, 85–100. Kraków: Eikon Plus.

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2020. “Love of Neighbor during a Pandemic: Navigating the Competing Goods of Religious Gatherings and Physical Health.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 196–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01031-6.

- Weinberger-Litman, Sarah L., Leib Litman, Zohn Rosen, David H. Rosmarin, and Cheskie Rozenzweig. 2020. “A Look at the First Quarantined Community in the USA: Response of Religious Communal Organizations and Implications for Public Health during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Religion & Health 59 (5): 269–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01064-x.

- Zavadilová, Tereza. 2020. “Pravda Evangelia a Jed Fake News [The Truth of Gospel and Poison of Fake News].” In Obraz Katolické Církve v Českých a Slovenských Médiích v Letech 2015–2018 [Image of the Catholic Church in the Czech and Slovak Media in the Years 2015–2018], edited by Petra Koudelková, 26–36. Praha: Karolinum.