Abstract

This case study focuses on the pastoral and communicative activity of priests from nine Roman Catholic dioceses during the first wave of Covid-19, i.e. from the beginning of the pandemic to approximately June 2020. The dioceses belong to all continents: two are in North America (Saint Augustine, USA, and Ciudad Victoria, Mexico); two in Africa (Isiro-Niangara, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Owerri, Nigeria); two in Europe (Valencia, Spain, and Tempio-Ampurias, Italy); and one each in South America (Duitama-Sogamoso, Colombia), Oceania (Parramatta, Australia), and Asia (Seoul, South Korea). A quantitative methodology was employed through a questionnaire-survey distributed to the clergy of these diocese, with the goal of learning how they communicated with their faithful and helped them to maintain their life of faith during the period of lockdown and restriction of movement. The survey was conducted online between February and April 2021. Findings show that while the pandemic has reduced the attendance of the faithful at church, priests have responded in various ways, trying to continue spiritual assistance.

1. Introduction

Since March 2020, the world population has been suffering, in different degrees and to various extents, from the pandemic of Covid-19, provoked by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). The pandemic has spared no ethnic, geographical or religious community. The global institution of the Catholic Church has experienced too, at the local level, the consequences in her own flesh: the closing of churches, downsizing of teaching and evangelizing meetings, limitation of social activities and even prohibition of liturgical celebrations.

While other articles in this special issue on Covid and the Church cover, among other things, theoretical aspects or media coverage of the pandemic, this case study focuses on the pastoral and communicative response of the local churches during the first months of the pandemic. Specifically, the study collects data from nine dioceses from all six inhabited continents: two from North America (Saint Augustine, in Florida-USA, and Ciudad Victoria, in Mexico); two from Africa (Isiro-Niangara, in Democratic Republic of the Congo or DRC, and Owerri, in Nigeria); two from Europe (Valencia, in Spain, and Tempio-Ampurias, in Italy); and one each from South America (Duitama-Sogamoso, Colombia), Oceania (Parramatta, New South Wales-Australia), and Asia (Seoul, South Korea).

This study covers the actions taken and perceptions experienced by priests, the pastors who are closest to the people, in dealing with the pandemic to fulfill their mission of serving the souls entrusted to them.

2. Theoretical framework

The methodology of this study is guided by the following research question: How have Roman Catholic priests responded pastorally and communicatively to the challenges posed by the first months of the pandemic Covid-19? Beyond other findings, the research attempts to offer an assessment of three different hypotheses (H):

H1) The pandemic had a negative impact on the pastoral care of the Catholic faithful;

H2) Catholic priests responded in the best possible way to the challenges posed by the pandemic;

H3) The pandemic prioritized digital priestly activities over physical presence and that trend will continue in the future.

In the Catholic and Christian tradition, the pastoral dimension is understood as the mission and group of activities that the Church and her ministers exercise concerning the giving of spiritual guidance and assistance. Theologically, the pastoral mission can be summarized in the tria munera or “three offices” that all the baptized, and ordained priests in particular, share with the founder of the Church, Jesus Christ (Vatican Council II Citation1965). They are the munus docendi (related to the duty to teach, based on Christ’s role as Prophet or Teacher), the munus sanctificandi (related to the duty to sanctify, based on Chris’s role as Priest), and the munus regendi (linked to the duty to shepherd, based on Christ’s role as King at the service of his People).

We cannot here delve into the theological implications of the concept of the tria munera. For our purposes, it will be enough to give some examples of their practical manifestations in order to understand their importance in the pastoral life of the priestly ministry and of the members of the Catholic Church, considering how much these activities are connected with communication.

Among other examples, some activities of the teaching office include preaching, giving catechesis, educating children, preparing couples for marriage, etc. The sanctifying office involves mainly the celebration and distribution of the seven Sacraments (Baptism, Eucharist, Penance, Confirmation, Marriage, Holy Orders and Anointing of the Sick) as well as the different liturgical celebrations (Mass, blessings, etc.). Finally, the governing office, while it certainly includes the organization and management of Church structures, mainly means a spiritual shepherding which implies the disciplinary, doctrinal and moral guidance of the People of God.

The relationship between religion and society has always attracted the interest of scholars. For example, the multi-disciplinary contributions of Woodhead and Catto (Citation2012) examined, among other aspects, the evolving role and status of churches within a growing process of secularization in society, manifested by the decline in Sunday church attendance (in all Christian denominations), the rise and diversification of alternative spiritualities and the increase of people not following any religion.

The arrival and global diffusion of Covid-19, much reported on and discussed on social media (Cinelli et al. Citation2020), has brought new challenges to churches. A particularly significant one has been the increased digitalization or digital mediation of church activities. This process of the transformation of religious communities, and their adaptation to digital environments has already been studied by many authors (Hadden, Bromley, and Cowan Citation2000; Dawson and Cowan Citation2004; Jenkins Citation2008; Hutchings Citation2011; Cheong et al. Citation2012; Spadaro Citation2014; Vitullo Citation2019). Among the most prolific authors is Campbell (Citation2005, Citation2010), who has often collaborated with other scholars (Campbell and Vitullo Citation2016).

In the field of the Roman Catholic Church, institutional adaptation to the digital environment has been studied by Arasa, Cantoni, and Ruiz (Citation2010). Of particular interest was a subsequent worldwide study on Catholic priests’ usage of ICTs (Cantoni et al. Citation2012).

As mentioned, the pandemic of Covid-19 has brought new challenges to the practice of religion. Campbell (Citation2020, Citation2021) has recently confronted the challenges of the pandemic for churches of different denominations. Other studies have focused on the impact on religious attendance (Alfano, Ercolano, and Vecchione Citation2020) and on the personal experiences of clergy ministry (Testoni et al. Citation2021). But one of the most significant studies—for the purpose of this paper, because of the similarities with ours—is that of Isetti, Stawinoga, and Pechlaner. They studied “how pastoral care and activities were performed in early 2020 during the lockdown period imposed to contain the Covid-19 pandemic, and what experiences were made in the Roman Catholic context, by analyzing a single [Italian] Diocese” (Citation2021, 358).

The studies mentioned, and other similar ones, were focused on particular geographical areas. They will be very well complemented by a study with a more global scale, such as ours.

Before explaining the methodological aspects of our study, two sections will be included. First, a brief description of the worldwide evolution of the first months of the pandemic, which had so many consequences in the decisions taken by governments at different levels (health, legal, financial…), and with notable repercussions on religious organizations. Secondly, a presentation of the main decisions taken by the leader of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis, and some of the Vatican departments (Congregations), which gave the framework for pastoral action at the national and local levels (bishops’ conferences and dioceses mainly) and stimulated the activities of priests at the community (parish) level.

3. Worldwide context

3.1. Pandemic in the world

At the writing of these lines, the evolution of the pandemic of Covid-19 and its consequences are still uncertain. Governments and health authorities at all levels are trying to cope with a phenomenon which has brought with it many polemics related to limitation of circulation, obligation of vaccination, lack of trust in pharmaceutical industries, abandonment of developing countries, etc.

The response has been different and followed diverse paces in different countries. In some cases, lockdowns have been long and very strict, in others the restrictive measures were more flexible. Obviously, the measures for containment the virus and the timing of their application varied according to the geographical area. It is not our goal to get into the history of the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic or the responses of health and public authorities to the emergency. However, a brief summary of the beginning of the pandemic will help us to better understand the data obtained in this case study.

On 31 December 2019, the Chinese government warned the World Health Organization (WHO) of an abnormal viral pneumonia found in 27 patients, with a first outbreak in the city of Wuhan in the Hubei region. The origin of the virus has been widely discussed. Most researchers consider that SARS-CoV-2 virus had a natural origin (Andersen et al. Citation2020; Gatta Citation2020). Nevertheless, some members of the scientific community do not discard the hypothesis of an involuntary leak from a Chinese lab (Norman Citation2021). The WHO commission of experts sent to Wuhan from January 10 to February 2021 did not exclude any possibility but has not given a definitive answer (WHO Citation2021).

Despite the virus diffusion, the WHO did not characterize Covid-19 as a pandemic until 11 March 2020, long after the Chinese authorities had decided to declare a lockdown, and when the virus had already crossed the mainland's borders in a widespread way. In Europe, for example, France was the first country to have the first three confirmed cases on 23 January 2020. In the initial phase, most governments did not realize the seriousness of the problem. Many of them only reacted when the numbers of infected and dead soared out of control.

Globally, as of 18 November 2021, there have been 254,847,065 confirmed cases of Covid-19, including 5,120,712 deaths, reported to the WHO, according to information on the website.

3.2. Decisions at the level of the Universal Church

It would be unfair to forget—and impossible to present in this study—all the actions and measures taken by the Church at the national and local levels. In this introduction we will limit ourselves to summarizing the main actions taken by the universal authority of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis; on a secondary level, we will mention the guidelines given by the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, the Vatican Dicastery in charge, among other tasks, of giving norms for the liturgical celebrations. Certainly, the actions of both the Pope and the Congregation for Divine Worship were not many, however they provided a point of reference for lower levels to concretize rules and recommendations. For example, in many dioceses and parishes, the Mass was transmitted online following Pope’s initiative, and bishops’ conferences and individual bishops promulgated criteria to be followed when celebrating the Sacraments in their territories, considering the Vatican’s indications and the public restrictions.

Faced with the advance of the pandemic in the world, Pope Francis played a particular role of leadership in pastoral response, specially through various decisions and initiatives taken in the first moments of the pandemic. On 8 March 2020, the Director of the Holy See Press Office, Matteo Bruni, announced that the Pope's Masses would be broadcast live on Vatican News and distributed to the media that requested it. This announcement came at a time when public celebrations were largely suspended for fear of contamination. Thus, from 9 March to 18 May 2020, the Pope offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in his personal chapel with live streaming while praying for people in need (Capelli Citation2021).

Two other events that happened during that same month of March deserve to be highlighted. The first was the visit of Pope Francis to the Roman Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore on 15 March to address a prayer to the Virgin; then, on foot, the Pontiff went to the church of San Marcello al Corso, to pray in front of the miraculous Crucifix that was carried in procession in 1522 during the Great Plague. The second event was on 27 March: the papal prayer in St. Peter's Square with the reading of the Word of God and commentary on it by the Pope, Eucharistic adoration and the blessing “Urbi et Orbi” [To the City (of Rome) and the World]. Linked to this blessing was the possibility of receiving a plenary indulgence. During this prayer, two symbols were in view: the icon of the Salus Popoli Romani (a traditional Roman image of the Virgin Mary) and the Crucifix from the church of San Marcello (Pope Francis Citation2021).

On its own, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments issued two decrees in the space of a week, on 19 March and 25 March 2020. Both decrees, “In times of Covid-19” and “In times of Covid-19 (II)” (Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments Citation2020), provided detailed rules for the liturgical celebrations of the coming feast of Easter, the most important Christian celebration of the calendar, in consideration of the physical limitations on church attendance and public activities.

At the level of communication, two aspects of the decrees merit attention, even though they may seem small details. Once the Bishops, in collaboration with the Episcopal Conferences, had established measures and read the Decree, they were invited to inform the faithful “of the time of the beginning of the celebrations, so that they can join in prayer in their own homes.” It was also suggested to bishops to “offer suggestions to help family and personal prayer.” Also, considering the different media that could have been used, the Congregation underlined the usefulness of “live, not recorded, telematic means of communication.”

Let us also underline in passing the spiritual and merciful approach that the Pope and his aides tried to give from the beginning to the Church response. An example of that was the Rosary initiated and presided over by Cardinal Angelo Comastri, then Archpriest of St Peter’s Basilica, every day starting at 12 noon, from March to May 2020.

In sum, many bishops’ conferences and dioceses around the world made decisions on liturgical and pastoral matters, taking into account the general framework provided by the Pope’s actions, the decrees of the Congregation for Divine Worship and also the safety measures indicated by the health authorities of their own countries. Although a majority of Catholics followed their bishops’ indications, some did not always accept them pacifically. For example, some protests happened online and also in presence to complain about the fact that grocery stores or pharmacies were open, because considered essential services, while churches remained closed.

4. Methodology

4.1. Dioceses sample

The nine dioceses of the sample are briefly presented in . The selection of the dioceses responded to a convenience sample, so it has no claim to be statistically representative. On the other hand, it would have been impossible to try it in such different contexts and in such a short period of time.

Table 1. Dioceses of the sample.

4.2. Questionnaire and survey

4.2.1. Elaboration

The elaboration of the questionnaire underwent several phases between mid-December 2020 and January 2021. Before it was sent out, a pre-test with eight individuals—six priests and two communication experts—was conducted 14–19 January 2021.

In all, the questionnaire was composed of thirty-six (36) questions, divided into three main sections: “The use of technologies” (Section A); “The changes in pastoral aspects” (B), and “The perspectives of the Church in the post-pandemic period” (C). Besides these it included a final section (D) with identifying questions on the age of the respondents, the number of years of priestly ministry and finally the demographics of the parishes.

The composition of the questionnaire was guided by the goal of understanding the actions carried out in the field by priests during lockdown. As a backbone, questions were structured around the three missions (offices) of the Church and therefore of its ministers, namely teaching, sanctifying, and governing. In the first section, it tried the survey tried to discover the digital aptitudes of the priests as well as their use of digital tools for pastoral activities, among other aspects. The second part of the questionnaire wanted to understand the conduct of the pastoral mission of the priests during the lockdowns or restriction of activities as well as the changes that took place in their pastoral activities. The final section focused on the priests’ own evaluation of the changes that occurred in pastoral ministry during the first months of the Covid-19 and in their expectations for the post-pandemic.

4.2.2. Distribution

With a few weeks of difference among dioceses, the period of sending out questionnaires and collection of data went from February to April 2021.

Researchers for each diocese adopted different formulas to reach the census of the survey. Most of them used direct communication to priests through WhatsApp (or other social media, such as Kakaotalk for Seoul) or/and email. Moreover, several were supported by a letter of recommendation from some ecclesial authority (the Bishop, Vicar General, etc.) in order to encourage responses from the diocesan clergy. In some cases (Africa), paper copies of the questionnaires were also distributed to facilitate the answers. The tool employed for filling in the online questionnaire was Google Survey, and anonymity was guaranteed (also in the few cases of printed questionnaires completed).

4.3. Validity and quality of the data

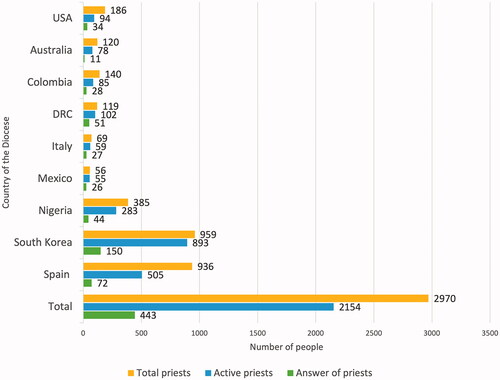

As indicated in , the number of priests who completed the questionnaire was of 443, that is 15% of the total priests in those dioceses (2970). However, if we consider only the 2154 active priests (which excludes retired, sick, etc.), the percentage of response rises to 21%. Because of the channels and the qualified contacts of the researchers, the authors are certain that the quality of response is even higher. The reason is that questionnaires were mainly answered by parish priests, who make up only a percentage of the total population of active priests.

Table 2. Ratio of responses/priests to the questionnaire by diocese.

A visual representation of the total number of priests and active priests for each diocese is available in .

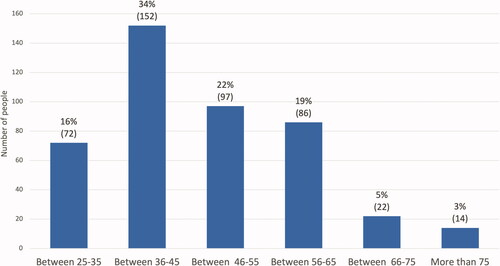

The distribution by age of the respondents was random []. Nevertheless, it seems normal that older priests were less keen to answer an online questionnaire which, in addition, was targeted to active parish priests. As an interesting aside, 85% of the sample (376 priests) were regular (daily) or heavy (many times daily) users of the internet.

In addition, an equal distribution of answers occurred regarding the size of priest’s community (D.36): around 30% of priest served in very small or small communities (less than 1000 members), 33% in medium size parishes (between 1000 and 5000), and 32% in big or very big communities (more than 5000).

A final observation on the questionnaire is the number of answers given by the 443 priests to the different questions: although one question reached only 67% of the sample (that is 297 out of 443), and another only 304 answers (69%), all other valid questions considered (26) surpassed 405 answers, with the average rate of answers for the whole questionnaire being 96% (424 out of 443).

The high value of the questionnaire cannot hide three limitations of this study. First, the survey focuses only on the first months of the pandemic, until June 2020, leaving out all the actions of the following months. Secondly, the pandemic and its social consequences had different intensity and evolution around the globe, while our study necessarily groups data in a unique cluster. Finally, it collected data from only nine dioceses, when the Roman Catholic Church counts around 3,000.

5. Findings

The answers to the 28 questions have provided a great amount of information. For the purpose of this study, we will focus our analysis on those responses that highlight the exercise of the three priestly offices. The aim is to look at how teaching, sanctifying and governing were affected by the pandemic.

A caveat is nevertheless useful. Although the analytical distinction recognized by the science of Theology among the tria munera is clear, in the life of the Church and in the activities of the priest the three offices are intertwined. For example, during the administration of the Sacrament of Penance, where the sanctifying office is predominant (granting the grace of forgiveness to sinners), there is also a teaching dimension (guidance, advice) and there might be present a shepherding element (direction to almsgiving or some other sanction imposed for the sinful action being confessed). In the analysis herein, we will categorize the different actions under the primary office implied.

We will start with the analysis of the teaching office and follow it with the study of the impact of the pandemic in the most important of the dimensions of priestly identity, that is to say the sanctifying office. Finally, the analysis will focus on the pandemic effects on the activity of the governing office.

5.1. Teaching office

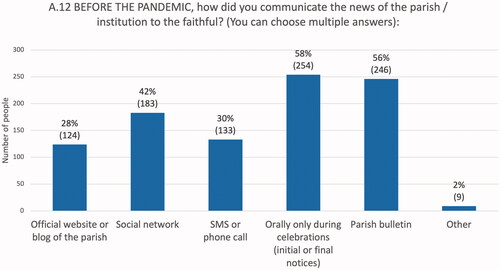

In order to study the priestly activities related to the teaching office, we will start by presenting what channels priests utilized to regularly inform their flock before the pandemic [] and how much social media were employed to transmit general information. We will also make mention of the impact of the pandemic on the creation of new digital channels in parishes.

Graph 3. Pre-pandemic information channels with the faithful (437/443 responses, 99% response rate).

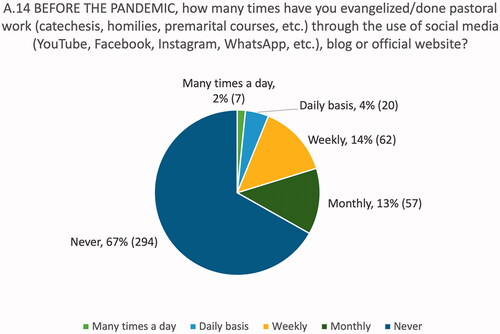

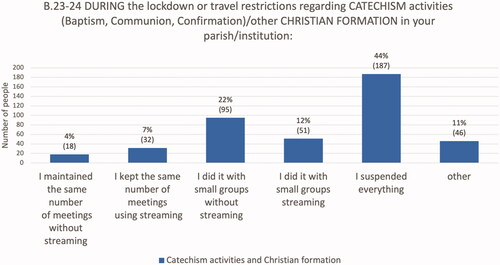

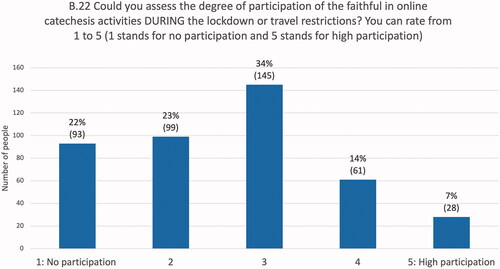

The next step is observing how many priests used social media for the task of evangelization before the arrival of the pandemic [] and how many of them employed social media during the first months of the pandemic for teaching activities (essentially Catechesis and other types of Christian education) []. The priests’ assessment of the participation of the faithful in those activities completes this section [].

Graph 5. Catechism and other Christian formation activities during the first months of the pandemic (428/443, 97%).

Graph 6. Participation of the faithful in online catechesis during the first months of the pandemic (426/443, 96%).

Before the pandemic:

As shown in , before the pandemic, most of the priests preferred to communicate verbally with the faithful during or at the end of religious celebrations (58%) or through the parish bulletin/billboard (56%). A significant percentage also did so through social media (42%), 30% chose to communicate through phone services (calls or text messages) and 28% through the parish website.

Before the pandemic, 42% of the priests who used social media sent news in a daily basis and another 45% did it weekly. Nevertheless, it is significant than 2/3 of the priests never considered using social media channels for activities related to evangelization (teaching office). The percentages of those who did it daily (6%), weekly (14%) or monthly (13%) were very low [].

Since most of the priests declared that they already had a website or social media account before the Covid explosion, it can be concluded that the pandemic influenced not so much the creation of digital media channels, but their usage, particularly with regard to social media (as we will see later in ).

Already a decade ago, Cantoni et al. (Citation2012) showed how a majority of Catholic priests evaluate positively the use of internet for personal study and prayer, and to keep in touch with faithful, but prefer face to face contact in pastoral ministry. This trend probably continues to be similar in the age of social media, although percentages may have slightly changed.

During the pandemic:

When priests were asked how much of the catechesis and other Christian activities they did online during the pandemic in contrast with before [, B.23 and B.24], results showed evangelization activities during that time in a negative light. Almost half of the priests (44%) suspended all formation activities when the lockdowns occurred, 26% kept up the activities in person (in some cases with physical restrictions) and only 19% did some activities online.

It appears evident that the traditional format of church teaching, i.e. in presence, continued to be seen by clergy as the most effective. With the available data, we can only make hypotheses about why most of the priests did not see other alternatives to meeting in person: among others, lack of interest, low technological expertise or scarcity of financial means.

The analysis of the 44% who “suspended everything” would require a proper study, considering aspects such as geographical distribution and countries’ digital usage. Nonetheless, the fact that 67% (as presented in ) did not consider social media for evangelization before the pandemic allows us to think that the physical restrictions found them unprepared to respond immediately to the challenge when Covid-19 arrived.

Education in the faith is one of the pillars in the growth of Christian life. Because of the pandemic, many catechism activities were necessarily given online. However, priests’ perception of the impact of the pandemic in the faith educational process of the faithful was also negative []. A total of 45% of the respondents assured us that participation in online catechesis was very low (23%) or nil (22%) and only 21% considered that it was slightly higher (14%) or much higher (7%).

5.2. Sanctifying office

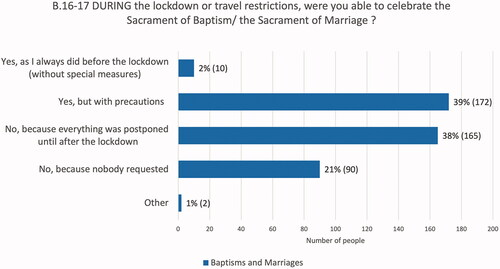

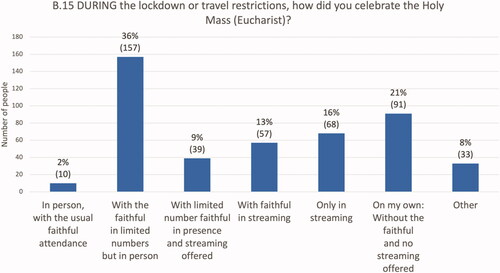

The distribution of Sacraments is one of the most characteristic and important priestly activities. In this survey, attention was focused on the celebration of the Mass or Eucharist [–], Baptisms and Marriages [], as well as other Sacraments and activities related to the spiritual assistance of the faithful [].

5.2.1. Mass

One of the priestly activities that most visibly showed the efforts of priest to adapt to the external circumstances was the celebration of the Eucharistic liturgy, or Mass []. Still in the first months of the pandemic, a majority of priests (59%) continued the celebration only in presence, whether with a limited number of faithful (36%), alone without a public (21%) or with the usual faithful attendance (2%).

Graph 7. Modalities in the celebration of Mass during the first months of the pandemic (437/443, 99%).

With regard to online activity, a total of 38% of the priests decided to stream the Mass, whether with a limited number of attendants in presence (13%), only in streaming (16%) or with the usual numbers of participants in presence but also with streaming (9%).

Two hypotheses come to mind to explain the low ratio of Mass streaming, in spite of the lockdowns and restrictions: one, in the first period many of clergy were not yet prepared (technically or personally) to do the streaming; secondly, many also considered that other streaming services, like the broadcasting of masses through local TVs or the Pope’s streaming Mass, were already valuable alternatives. It is worthwhile to mention here that the Pope stopped broadcasting his daily Mass when the restrictive measures were loosened, as if he were trying to remind Church ministers and faithful of the importance of going back to physical participation.

Although almost 60% of the clergy did not stream the Mass, it is known that many other priests worldwide tried to adapt to the circumstances created by Covid, that is, the restrictions imposed by the civil authorities, and generally accepted by the religious national governing bodies. In many cases, this adaptation included the transmission of the Mass through different online services (WhatsApp, Facebook live, YouTube, etc.). Nevertheless, more than half of those who did so in our sample (52%) considered it difficult or very difficult to stream the celebration, and only 22.5% thought it was easy or very easy. These numbers reflect the need for technical training on the part of the clergy, considering that the pandemic may last or return in the future.

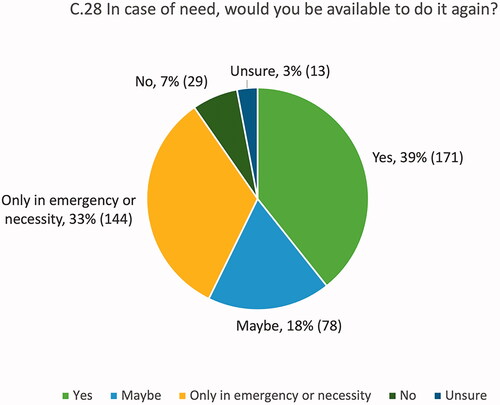

Looking ahead, 39% of the priests surveyed do not have doubts about reusing the streaming channels for the transmission of the Mass in the future [], but still more than half (51%) are not enthusiastic or are available to repeat the experience only if needed. Only 7% refuse to repeat the experience.

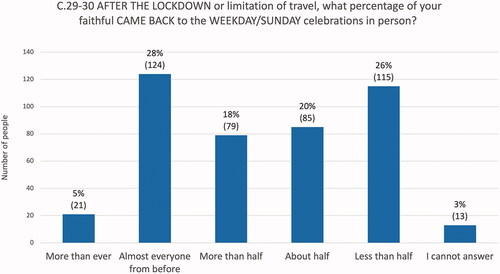

Among the commitments of practicing Catholics, physical participation at the Holy Mass on Sundays is required (if there are no important obstacles like illness, emergencies or unavoidable work commitments). Some devout Catholics also assist at Mass during the week. Considering that during the first wave of the pandemic lockdowns were imposed, churches were closed in many places and public celebrations stopped or limited, priests were asked to give their perception of how much the faithful had returned to the Eucharistic celebration with the reopening of the churches. The differences in the priests’ perception between the return to Sunday or weekday celebrations by the faithful were not significant, so we decided to consider the average data of both celebrations [].

Graph 9. Number of faithful returned to church after the first months of the pandemic (Weekday & Sunday average: 435.5/443, 98%).

Almost 2/3 of the priests (64%) perceived that less people returned to Mass celebrations. 28% considered that almost everyone had returned and only 5% said that more people were back to church. Independently of the differences between dioceses, it seems clear that the consequences of Covid (physical restrictions, fear of contagion, etc.) have had an impact on the spiritual life of the faithful.

5.2.2. Baptism & marriage

The data related to the administration of Baptisms and Marriages confirm that the sacramental life of ordinary Christians suffered a serious setback with the arrival of the pandemic []. In both cases, these sacraments were largely not celebrated during the first Covid-19 wave (58% for Baptisms and 59% for Marriages). They were either postponed until the end of the lockdowns and restrictions on movement or they were not requested by the faithful. Nonetheless, an important percentage of priests (42%) continued to celebrate both Baptisms and Marriages, with precautions in most cases.

Observing , we can conclude that, while priests were generally available to assist the faithful, the external measures and its consequences in people’s life prevented this assistance: fear of incurring sanctions, anxiety about contagion, civic sense of obedience to public and religious authorities, etc. It has to be also considered that the sacraments of Baptism and Marriage play an important social role and many people preferred to postpone them to allow the participation of relatives and friends in better times. This aspect says much about the low theological comprehension, in ordinary Christians, of the sense of the Christian sacraments (as means to receive the grace of God) rather than mere social rituals.

5.2.3. Spiritual assistance

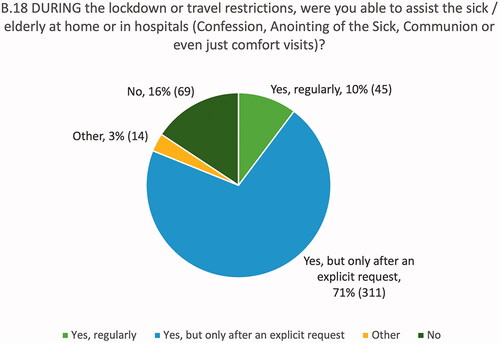

Spiritual assistance is a generic term that groups many different activities proper to the sanctifying office like hearing Confessions, providing the Anointing of the Sick, distributing Communion or other activities of spiritual ministry for groups or individuals.

For privacy reasons, no specific numbers of spiritual assistance activities were asked of the respondents, but only the frequency of these activities during the pandemic []: 10% of the priests exercised them regularly and 71% after an explicit request. Only 16% completely stopped this kind of service. These percentages show how, despite the restrictions, a great majority of priests showed proximity to the faithful entrusted to them. Furthermore, in most cases the assistance was carried out in very difficult conditions: using masks, social distancing, open and external spaces, time limitations, and so on.

An interesting observation can be made here. While 44% of the priests suspended formation activities (teaching office) during the first months of the pandemic (), only 16% did so regarding spiritual assistance (). Among others, two plausible conjectures can be given: first, formation activities are usually given collectively, to groups, which was not possible during the first months of the pandemic; and second, these activities can easily be replaced (at least temporally or in some instances) by personal study, research, reading, listening audios or watching videos. On the contrary, spiritual assistance activities are more personal and need the presence of the minister (the Sacrament of Confession, for example) or at least are more convenient in presence (conversations about conscience issues proper to spiritual guidance).

5.3. Governing office

The governing office embraces different aspects such as the spiritual shepherding of the faithful or the management and organizational matters proper to run a church organization (i.e. parish).

The communication of the priests with their faithful pre-pandemic has been presented already in section 5.1. Covid-19 changed the dynamics: from a mainly informative approach (pre-pandemic) to a more managerial, relational and spiritual use of the media (during the pandemic). The enormous potential of digital channels made them adaptable instruments for all kinds of activities of all three priestly offices (teaching, sanctifying and governing).

We now propose the data analysis on the priests’ relationships with some of their main stakeholders (faithful and parish collaborators), since it responds directly to the managerial and governing dimension.

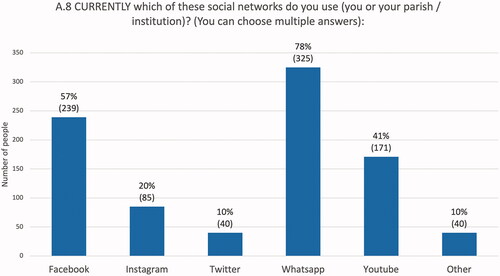

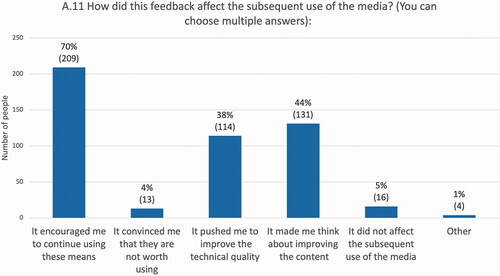

In this sense, the data offered is on what specific social media were used by priests during the pandemic [] as well as on the influence of the faithful’s feedback on the use of social media by priests []. Of much interest also is the level of interest of parish collaborators []. Another concrete activity that shows the impact of Covid in parish activities is the evolution of parish meetings before and during the pandemic [Graphs 15 and 16].

Finally, a specific activity like the aid activities provided by the parish to the needy during the pandemic is presented []. This activity includes both spiritual attention to the faithful and material assistance, but surely includes a substantial organizational facet.

…

General population use of social networks and other social media refers mainly to relational, entertainment and informative goals (Arasa et al. Citation2012). Priests [] seem to be big users of WhatsApp (78%), medium users of Facebook (57%), significant users of YouTube (41%) and low users of other social media (Instagram, 20%; Twitter: 10%; and other social, 10%). Pretty significant is the fact that clergy possesses and uses on average 2.14 social media accounts per priest.

Since more than 1/3 of the priests (34%) received feedback from the faithful on the use of the media during the pandemic, it was of interest to know what influence this feedback had []. A great majority of priests declared themselves to feel encouraged by the faithful’s feedback to use such media in the future and improve, whether with the content or technically. Only 5% declared themselves not to have been influenced at all.

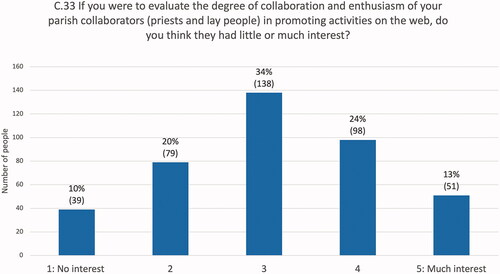

With regard to the level of interest of the priest’s collaborators in the use of the social media for the parish activities, the priests’ perception was much diversified []: while 36% considered it positive or very positive, 29% also recognized that some were not interested at all or not very enthusiastic. Based on these data, the future improvement of digital training for priestly ministry will probably need to take also into account a greater commitment and motivation on the part of their collaborators.

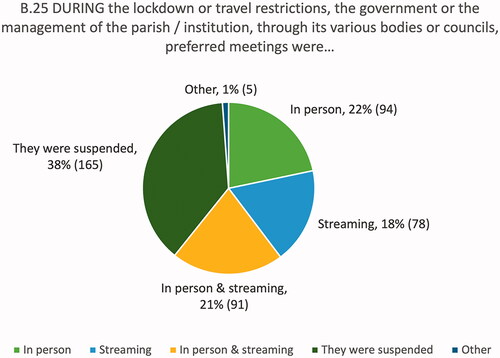

Parish meetings are direct way of managing the regular organization activities. For that reason, it was very indicative to know what happened with those meetings during the first months of the pandemic []. A total of 38% of the priests suspended parish meetings during the pandemic, but 61% kept them (whether in person, 22%, in streaming, 18%, or in both modalities simultaneously, 21%).

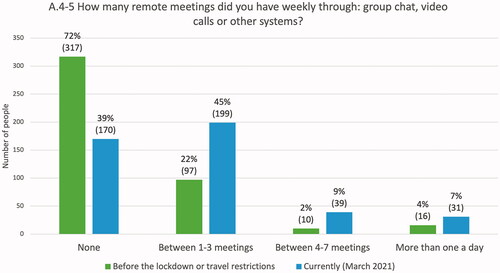

How much the frequency of the meetings varied before and during the pandemic completes the perspective []. Although 27% (123) of the priests already organized some kind of online meetings before the pandemic, a great majority didn’t (72%, 317). With the arrival of the Covid restrictions, the number of priests who never organize meetings online decreased to 54% (170). During the first months of the pandemic there was also a logical increase of the number of meetings online. Considering the evolution of the pandemic, numbers have probably continued to grow towards a major digitalization of meetings for parish work.

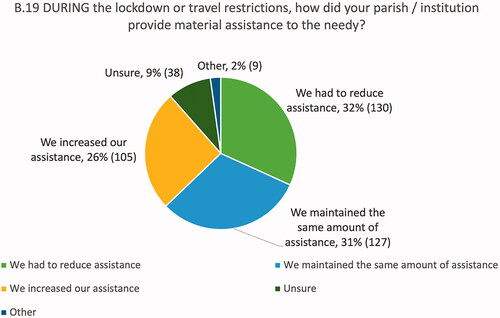

Finally, charitable activities such as assistance to the needy is presented []. Charitable services are concrete manifestations of the shepherding office that priests live in fulfillment of their vocation of service. The Covid restrictions had also an impact on this dimension, since 32% had to reduce the aid given to the needy. Almost a third (31%) keep the same aid and, paradoxically, 26% were able to increase their charitable activities.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Responses to the hypotheses

Our case study has focused on the pastoral attention that Catholics priests gave to their flocks during the first months of the pandemic of Covid-19, essentially between March and June 2020. While the data obtained through the questionnaire responded to by 443 priests were very significant, it is not possible to generalize the findings, since this was a convenient sample of nine dioceses worldwide. Nonetheless, it is possible to respond to the three hypotheses proposed initially and offer some final reflections.

Hypothesis 1. The pandemic had a negative impact on the pastoral care of the Catholic faithful.

In the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, parish activities of all kinds such as liturgical celebrations, work meetings, social events, etc., were suspended. Also, the administration of Sacraments (Baptisms, Marriage, etc.) was impeded or largely reduced. Moreover, only a percentage of the parishes offered catechesis and other Christian formation activities (preparation for marriage, for instance) with meetings online or in small groups in presence. Furthermore, even if churches were accessible, the faithful avoided agglomerations due to fear of contagion and fulfillment of government-imposed containment measures. All these elements hampered the community life of the Church, substantially confirming hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2. Priests responded in the best possible way to the challenges posed by the pandemic.

Through this investigation, it was found that many priests in the early days of the pandemic tried in various ways to reach believers, but since pastoral activities are mainly conducted within the physical boundaries of churches, they found themselves unprepared for an emergency situation such as the present one. This poor initial response to using alternative methods of contact with the faithful also had a negative effect on the believer’s practices, which probably was one of the reasons that led to the decrease in participation in the Mass on the part of a large number of the faithful.

Conversely, a good number of priests have shown a high level of courage and care and have done their best to keep up personal attention (visits to hospitals, hearing confessions, anointing the sick…). This study cannot prove scientifically the fact that, as media have extensively reported, there has been a huge death-toll of people on the front line of the response to Covid, principally the health and medical personnel. Among them, there were also many priests who risked their lives consoling the sick and their families and giving the last Sacraments. In sum, if physical limitations reduced the participation of the faithful at church, on the other hand personal initiatives by priests seemed to be very significant, leaving hypothesis 2 partially confirmed.

Hypothesis 3. The pandemic prioritized digital priestly activities over physical presence and that trend will continue in the future.

Prior to the pandemic, most parishes did not provide important services such as catechesis, pre-matrimonial courses or homilies through social media. Thus, many of the priests had a hard time streaming liturgical celebrations during the period of lockdown or limitation of people’s attendance at church.

In some cases, this initial difficult situation was overcome rather quickly, as most parishes already had official sites and social media accounts before the pandemic, and others opened them during the lockdowns. Furthermore, a majority of priests who use them were willing to invest and improve the technological tools and content offered online in the future. However, the pandemic’s influence was not so much in the creation of digital media channels, but in the usage of them, particularly with regard to social media.

It is expected that pastoral activities in online format will increase in the future. But this does not mean a complete digitalization of pastoral activity. Not only because the physical dimensions of the Sacraments are essential in the Catholic Faith, but also because of the importance of community life. Pastoral activities conducted only through social media can alienate the faithful from community life and foster passive participation by allowing them to be satisfied with the virtual format. After the pandemic, the Church will have to rethink how to best use digital technologies as means of communication between churches and faithful for pastoral purposes. At the same time, the use of new technologies, which can be useful for some population sectors, may exclude elders or non-privileged faithful unfamiliar with the use of the Internet.

In short, the online format has come to stay, not to substitute for physical presence, but to parallel it with new usages and activities. Despite an expected increase of the digital activities by the clergy in their three dimensions of teaching, sanctifying and shepherding, the priestly ministry will always prioritize actions in presence. This conclusion denies or partially disproves hypothesis 3, since communication and pastoral care of the post-pandemic Church will be a mix between presence and online.

6.2. Final reflections

As the pandemic is still ongoing, it is difficult to predict the future. What is undeniable is that the Covid-19 pandemic has produced an upheaval of confusion worldwide at all levels: low government response to the first wave of the virus; high mortality and fear in the population; medical uncertainties; political use and limitation of individual rights through restrictive measures; contradictory messages on vaccines’ effects and side effects; greater polarization in the social media debate, etc. This situation has generated despair and disenchantment in civil society and has deepened the lack of trust in institutions (Pujol, Narbona, and Díaz Citation2021).

In his Encyclical letter Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis said:

As I was writing this letter, the Covid-19 pandemic unexpectedly erupted, exposing our false securities. Aside from the different ways that various countries responded to the crisis, their inability to work together became quite evident. For all our hyper-connectivity, we witnessed a fragmentation that made it more difficult to resolve problems that affect us all. Anyone who thinks that the only lesson to be learned was the need to improve what we were already doing, or to refine existing systems and regulations, is denying reality. (Pope Francis Citation2020)

Civil authorities are still coping with the public health crisis and no time has been given to studying the overall implications of the Covid phenomena. From an ecclesial perspective, church authorities have dedicated a good deal of effort to fulfilling government regulations, although some attempts to focus on the existential consequences and the sense of the sorrow have not been missing. Future studies may focus more on the perception and reaction that Catholic faithful had with regard to Church and civil authorities’ decisions facing Covid-19. The duration of the pandemic has produced social stress and strained collective resilience.

In any case, the first months of the pandemic have been a learning experience and a shortcut to learning from mistakes and omissions. In this sense, the Church should consider this experience as a preparation for future pandemics, climate disasters or other circumstances that will require sustaining Christians in their faith life through personal and physical means as well as through digital tools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Arasa

Daniel Arasa has a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism (UAB, 1995). From 1994 to 1997 he worked as a journalist for Europa Press news agency, Spain. He then earned a Bachelor’s in Theology (Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome, 1999), a M.A. in Television and Radio (SMU, Dallas, 2001), and a PhD in Social Institutional Communications in 2001 at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross. In 2001, he started teaching at this same university, where he is currently Dean of the School of Church Communications and Professor of Strategic Communications. In March 2021, he was named Consultor of the Vatican Dicastery for Communications. His main research interests are institutional communications and online religious communication, particularly of Catholic institutions. He is author of Church Communications Through Diocesan Websites. A Model of Analysis (2008) and is co-editor of Religious Internet Communication. Facts, Trends and Experiences in the Catholic Church (2010), Church Communication and the Culture of Controversy (2010) and Church Communications: Creative Strategies for Promoting Cultural Change (2016).

Lidia Kim

Juhyun (Lidia) Kim Born in Seoul (South Korea) in 1991, Kim graduated in ‘Arts in Broadcasting Journalism’ at the Dong-ah Institute of Media and Arts in South Korea in 2016. In 2021 she obtained her Master’s degree in Church Communications at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome (Italy), and is currently working on her PhD in Church Communications at the same university.

Jean-Florent Angolafale

Jean-Florent Angolafale Priest of the Diocese of Isiro-Niangara (Democratic Republic of Congo). After 3 years of pastoral experience in a rural parish, he was sent to study Institutional Social Communications at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, where he obtained a Bachelor's in Communications in 2021. For the time being, he is continuing his doctoral research at the same university. He also has degrees in Philosophy and Theology.

Daniele Murrighili

Daniele Murrighili Deacon of the Catholic diocese of Tempio-Ampurias. He graduated in theology from the Theological Faculty of Sardinia in Cagliari and in Institutional Social Communications from the School of Communications of the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome. At present, he holds the role of Collaborator at the Episcopal Seminary of the Diocese of Tempio Ampurias and Director of the Diocesan Office for Social Communications, which is being established.

References

- Alfano, Vincenzo, Salvatore Ercolano, and Gaetano Vecchione. 2020. “Religious Attendance and COVID-19. Evidences from Italian Regions.” CESifo Working Paper 8596. https://www.cesifo.org/en/publikationen/2020/working-paper/religious-attendance-and-covid-19-evidences-italian-regions.

- Andersen, Kristian G., Andrew Rambaut, W. Ian Lipkin, Edward C. Holmes, and Robert F. Garry. 2020. “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2.” Nature Medicine 26 (4): 450–452. (doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9.

- Arasa, Daniel, Lorenzo Cantoni, and Lucio Adrián Ruiz, eds. 2010. Religious Internet Communication: Facts, Trends and Experiences in the Catholic Church. Rome: EDUSC.

- Arasa, Daniel, Lorenzo Cantoni, Emanuele Rapetti, Stefano Tardini, Sara Vannini, and Lucio Ruiz. 2012. “Priesthood and the Internet: The International Research Picture.” In Church Communications: Identity and Dialogue, edited by José María La Porte and Bruno Mastroianni, 227–246. Rome: Edizione Sabinae.

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2005. Exploring Religious Community Online. We Are One in the Network. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2010. When Religion Meets New Media. London: Routledge.

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Alessandra Vitullo. 2016. “Assessing Changes in the Study of Religious Communities in Digital Religion Studies.” Church, Communication and Culture 1 (1): 73–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23753234.2016.1181301.

- Campbell, Heidi A., ed. 2020. Religion in Quarantine: The Future of Religion in a Post-Pandemic World. Digital Religion Publications. doi:https://doi.org/10.21423/distancedchurch.

- Campbell, Heidi A., ed. 2021. The Distanced Church: Reflections on Doing Church Online. Digital Religion Publications. doi:https://doi.org/10.21423/distancedchurch.

- Cantoni, Lorenzo, Emanuele Rapetti, Stefano Tardini, Sara Vannini, and Daniel Arasa. 2012. “PICTURE: The Adoption of ICT by Catholic Priest.” In Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture. Perspectives, Practices and Futures, edited by Paulina Hope Cheong, Peter Fisher-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfren, and Charles Ess, 131–149. New York: Peter Lang.

- Capelli, Benedetta. 2021. “Vicino nella distanza. Un anno fa la prima Messa in diretta da Santa Marta.” Vatican News, March 9. Accessed 24 November 2021. https://www.vaticannews.va/it/papa/news/2021-03/papa-francesco-messa-santa-marta-anniversario.html.

- Cheong, Paulina Hope, Peter Fisher-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfren, and Charles Ess, eds. 2012. Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture. Perspectives, Practices and Futures. New York: Peter Lang.

- Cinelli, Matteo, Walter Quattrociocchi, Alessandro Galeazzi, Carlo Michele Valensise, Emanuele Brugnoli, Ana Lucia Schmidt, Paola Zola, Fabiana Zollo, and Antonio Scala. 2020. “The COVID 19 Social Media Infodemic.” Scientific Reports 10 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5.

- Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. 2020. “Decree - In time of Covid-19 (II).” Accessed 25 March. https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccdds/documents/rc_con_ccdds_doc_20200325_decreto-intempodicovid_en.html.

- Dawson, Lorne L., and Douglas E. Cowan, eds. 2004. Religion Online: Finding Faith on the Internet. New York: Routledge.

- Gatta, Raffaella. 2020. “SARS-CoV-2: quali sono le origini della pandemia del nuovo coronavirus?” Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri – IRCCS. April 7. Accessed 24 November 2021. https://www.marionegri.it/magazine/coronavirus-origine.

- Hadden, Jeffrey K., David G. Bromley, and Douglas E. Cowan, eds. 2000. Religion on the Internet. Religion and the Social Order, Vol 8. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hutchings, Tim. 2011. “Contemporary Religious Community and the Online Church.” Information, Communication and Society 14 (8): 1118–1135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.591410.

- Isetti, GiuliaElzbieta, Agnieszka Stawinoga, and Harald Pechlaner. 2021. “Pastoral Care at the Time of Lockdown: An Exploratory Study of the Catholic Church in South Tyrol (Italy).” Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10 (3): 355–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/21659214-bja10054.

- Jenkins, Simon. 2008. “Rituals and Pixels. Experiments in Online Church.” Online – Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 3 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.11588/rel.2008.1.390.

- Norman, Carolyn. 2021. “The Mysterious Case of the COVID-19 Lab-Leak Theory”. The New Yorker, October 12. https://www.newyorker.com/science/elements/the-mysterious-case-of-the-covid-19-lab-leak-theory.

- Pope Francis. 2021. Why Are You Afraid? Have You No Faith? Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- Pope Francis. 2020. “Encyclical Letter Fratelli tutti on Fraternity and social friendship.” October 3. https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20201003_enciclica-fratelli-tutti.html

- Pujol, Jordi, Juan Narbona and José María Díaz, eds. 2021. Inspiring Trust. Church Communications & Organizational Vulnerability. Rome: Edusc.

- Spadaro, Antonio. 2014. Cybertheology. Thinking Christianity in the Era of the Internet. Translated by Maria Way. New York: Fordham Press.

- Testoni, Ines, Silvia Zanellato, Erika Iacona, Cristina Marogna, Paolo Cottone, and Kirk Bingaman. 2021. “Mourning and Management of the COVID-19 Health Emergency in the Priestly Community: Qualitative Research in a Region of Northern Italy Severely Affected by the Pandemic.” Frontiers in Public Health 9 (9): 622592. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.622592.

- Vatican Council II 1965. “Decree on the Ministry and Life of Priests Presbyterorum ordinis.” December 7. https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decree_19651207_presbyterorum-ordinis_en.html

- Vitullo, Alessandra. 2019. “Multisite Churches. Creating Community from the Offline to the Online.” Online – Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 14. doi:https://doi.org/10.17885/heiup.rel.2019.0.23947.

- Woodhead, Linda, and Rebecca Catto, eds. 2012. Religion and Change in Modern Britain. London: Routledge.

- World Health Organization. 2021. “WHO Calls for Further Studies, Data on Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Virus, Reiterates That all Hypotheses Remain Open”. March 30. https://www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2021-who-calls-for-further-studies-data-on-origin-of-sars-cov-2-virus-reiterates-that-all-hypotheses-remain-open. The full report “Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus” is available at https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus/origins-of-the-virus.