Abstract

We present the results of a rapid avian inventory conducted September 2012 in the vicinity of Boanamo, within the Territorio Étnico Waorani and Parque Nacional Yasuní, Orellana and Pastaza provinces, Ecuador. Our inventory is the first of its kind from within the Territorio Etnico Waorani, and was carried out using visual and auditory detections made during a 16-day survey. We recorded 362 species of birds during the survey, a number that is around 60% of the expected bird community from this previously unexplored area. We include both qualitative and quantitative natural history information, primarily concerning reproductive behavior, for 41 species.

Introduction

The Yasuní Biosphere Reserve, located in the Amazon region of Ecuador, is part of UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Program that includes the Territorio Étnico Waorani and Parque Nacional Yasuní and a buffer zone, together encompassing around 1,682,000 hectares of this western Amazonian habitat. It is located in one of the most biodiverse areas on earth [Citation1–Citation3], in part because of its unique location at the intersection of the eastern Andean foothills, the western Amazon, and the Equator [Citation4,5], yet it is under increasing pressure to allow road development for the exploitation of oil reserves [Citation4,6,7]. Somewhat surprisingly, there are few published, complete avifaunal inventories carried out within the reserve [Citation8–Citation11], but many studies have examined portions of the local avifuana (e.g. understory communities) or have been focused on specific species [Citation1,12–29]. Thus, though the Ecuadorian avifauna is fairly well known [Citation30–Citation34], and a fair number of informal species lists are available at the plethora of tourist lodges in the region, such lists are largely unpublished and have not been evaluated within a scientific framework [Citation35,36]. The detailed distributions of many Amazonian species, there for, remain poorly described, in part due to the inaccessibility of much of this region. Furthermore, although recent years have witnessed a significant increase in studies on the reproductive habits of birds in Ecuador’s Amazonian lowlands [Citation37–Citation57], the breeding ecology of most species remains undocumented in eastern Ecuador. In an effort to rectify this, we here provide a preliminary survey of the avifauna of a poorly explored region of Ecuador’s Amazon, and supplement this with observations on the reproductive biology and natural history of 41 species.

Methods

We surveyed the avifauna in the vicinity of the indigenous Waorani community of Boanamo (01°15′45.38″S, 76°23′14.55″W) in eastern Ecuador from 16 September to 1 October 2012. Boanamo is located at the confluence of the Río Cononaco and Río Aurino at the border between the Pastaza and Orellana Provinces, and our survey included an area of roughly 25 km2 surrounding the community. Our avifaunal inventory was part of a larger biotic inventory funded by Pollywog Productions as part of the documentary feature film, Yasuni Man, and carried out in cooperation with the Waorani communities of Boanamo and Bameno. For additional information about the study area, see the concurrently conducted mammalian data published by Tirira & Killackey [in review] We accessed as much of the study area as possible via a system of hunting trails with a combined length of approximately 12 km and via ca. 10 km of rivers and streams (Río Cononaco, Río Aurino, Estero Araña).

HFG and DG were primarily responsible for assessing the presence and relative abundances of avian species, making daily excursions from the community. They recorded all vocalizations and visual detections in a non-systematic manner, but with roughly equal amounts of time spent in all accessible areas of the study area. Each area was surveyed on at least two days and at least one night. Taxonomy and nomenclature follows Remsen et al. [Citation58] and all sub-specific designations are based on currently understood distributions [Citation59] and the taxonomy of del Hoyo and Collar [Citation60].

Results & discussion

We recorded 362 species of birds during our survey period (Appendix 1). Given that this is the first avian species survey from this remote area, and that it was temporally limited, we expect that additional species will be recorded with additional survey work. The clearing of forest for habitation and agriculture in our survey area is extremely limited, and it is worth pointing out that some of the species lacking in our inventory, but included in the avifauna of other locations in Ecuador’s Amazon, are species generally associated with urban areas, open habitats, or second-growth forest, and may truly be absent. In particular, the absence of species such as Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris (J. F. Gmelin, 1788), Lineated Woodpecker Hylatomus lineatus (Linn., 1766), House Wren Troglodytes aedon Vieillot, 1809, and Blue-black Grassquit Volatinia jacarina (Linn., 1766), are suggestive of the mature forest nature of our survey site. Additional species may also be absent from our survey due to their use of more specific habitats that were not found within our survey area (e.g. large rivers, second-growth river islands, oxbow lakes, large patches of Guadua bamboo), most notably: Neotropical Cormorant Phalocrocorax brasilianus (J. F. Gmelin, 1789); Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus (J. F. Gmelin, 1789); Greater Ani Crotophaga major J. F. Gmelin, 1788; Dark-breasted Spinetail Synallaxis albigularis P. L. Sclater, 1858); Black-and-white Tody-Flycatcher Poecilotriccus capitalis (P. L. Sclater, 1857); Masked Tityra Tityra semifasciata (Spix, 1825); Brown-chested Martin Progne tapera (Linn., 1766); Blue-black Grassquit Volatinia jacarina (Linn., 1766). The lack of an additional subset of species, is almost certainly explained by their naturally low population densities or difficulty to detect (e.g. raptors, puffbirds). Noteworthy records and natural history observations are discussed below.

Crotophaga ani Linnaeus, 1758 Smooth-billed Ani (Figure (f))

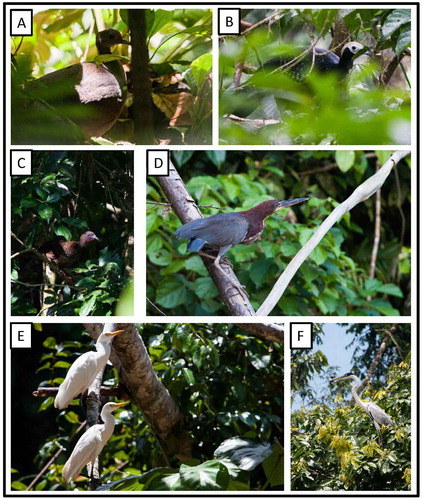

Figure 1. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Great Tinamou Tinamus major peruvianus; (B) Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile c. cumanensis; (C) Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis g. guttata; (D) Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma l. lineatum; (E) Cattle Egret Bubulcus i. ibis; (F) Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Figure 2. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Greater Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes melambrotus; (B) Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea; (C) Double-toothed Kite Harpagus b. bidentatus; (D) Great Black Hawk Buteogallus u. urubitinga; (E) Gray-winged Trumpeter Psophia crepitans napensis; (F) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius; (G) Sunbittern Eurypyga h. helias. Photos H. F. Greeney.

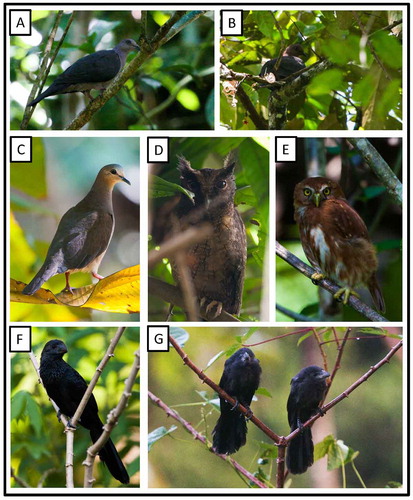

Figure 3. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Plumbeous Pigeon Patagioenas plumbea bogotensis; (B) Ruddy Pigeon Patagioenas subvinacea ogilviegranti; (C) Gray-fronted Dove Leptotila rufaxilla dubusi; (D) Tropical Screech-Owl Megascops choliba crucigerus; (E) Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl Glaucidium brasilanum ucayalae; (F) Smooth-billed Ani Crotophaga ani; (G) Smooth-billed Ani fledglings. Photos H. F. Greeney.

On 19 September 2012, we observed a large group of anis foraging at the edge of the Boanamo community. Within the group were at least four stub-tailed fledglings, still not able to fly well. We did not observe them being fed by adults, but they were clearly dependent upon their parents at this stage. The fledglings were still traveling with the adults on the following day, at which time we photographed them as they paused to preen in the sun ((g)).

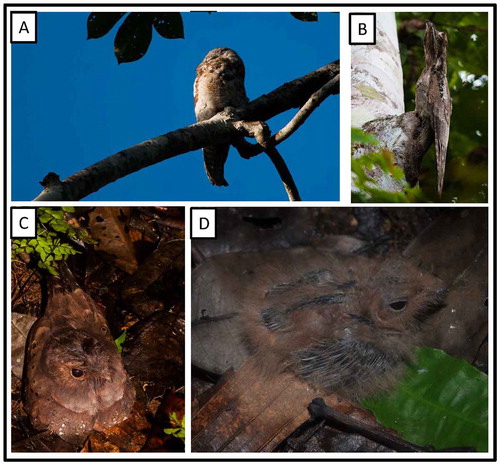

Nyctiphrynus o. ocellatus (Tschudi, 1844) Ocellated Poorwill

On 30 September, at 1850 h we found a nest of Ocellated Poorwill when an adult flushed from the nest ((c)) as we approached to within 1.5 m. As is typical of this species [Citation61,62], the nest was on fairly level ground and showed no indication of material arrangement or construction. A few fern leaves provided some shelter for the nest site, about 30 cm above the adult, but the nest was otherwise fairly exposed. It was in an area of terra firme forest with an intact canopy and fairly open understory. The adult was brooding a single, young nestling still covered in natal down ((d)). Otherwise, this species was not particularly abundant in our study area, and adults were only occasionally heard calling at night.

Figure 4. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Great Potoo Nyctibius g. grandis; (B) Common Potoo Nyctibius g. griseus; (C) adult Ocellated Poorwill Nyctiphrynus o. ocellatus brooding nestling in nest; (D) young nestling of Ocellated Poorwill. Photos H. F. Greeney.

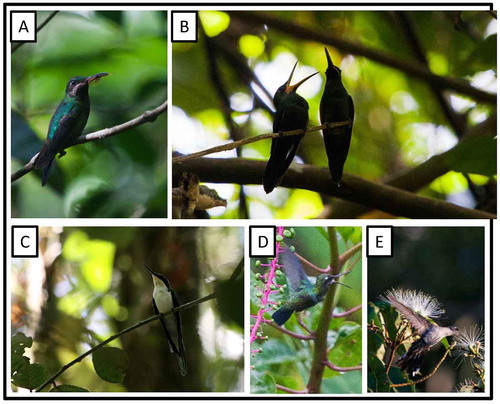

Topaza pyra amaruni Hu et al., 2000 Fiery Topza (Figure )

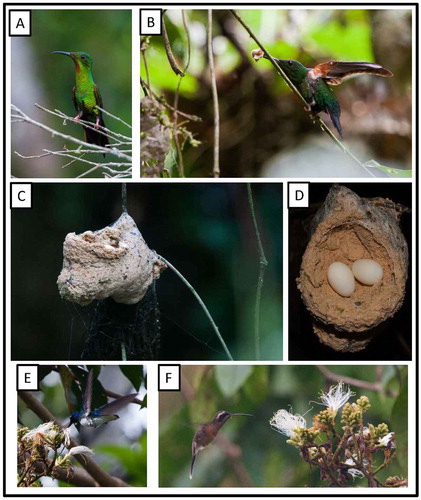

Figure 5. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Firey Topaz Topaza pyra amaruni, adult male; (B) Firey Topaz, adult female stretching her wings with nesting material in her bill; (C) Firey Topaz, nest; (D) Firey Topaz, nest with two freshly-laid eggs; (E) White-necked Jacobin Florisuga m. mellivora, feeding on Inga sp. flowers at forest edge; (F) Black-throated Hermit Phaethornis a. atrimentalis, feeding on Inga sp. flowers at forest edge. Photos H. F. Greeney.

We found an active nest built 1.3 m up, directly over a small in-forest stream (ca. 2 m wide). The nest was composed entirely of a very fine, densely packed seed down of unknown origin, and tightly bound with spider web such that it had an almost putty-like consistency. It was attached by one side to what appeared to be the remains of an old nest of the same species. This older nest was attached (the material partially wrapped around) a thin aerial rootlet hanging from epiphytes 2.6 m above the nest. The support forked at the attachment point into three smaller rootlets. A small amount of detritus (dark rootlets) had, apparently naturally, accumulated here, and these provided an additional anchoring point for the nest. The supporting rootlet was growing into the stream bed below, creating a fairly stable substrate. Upon our original approach to the nest at 10:30 h, on 27 September, no adult was present. While we examined the nest the female arrived with a small amount of material in her bill, but soon left the area without adding it to the nest. At this time the nest contained a single, completely undeveloped egg, cool to the touch. The egg measured 17.0 × 11.4 mm and weighed 1.194 g. When we returned at 09:00 h on 30 September the female flushed from the nest as we approached to within 6 m, despite the fact that we had been clearly visible on our approach from over 15 m away. At this time, the nest contained two eggs with no visible signs of development. The second egg also measured 17.0 × 11.4 mm, and weighed 1.198 g. At this time the first egg weighed 1.186 g. The nest and eggs described here are similar to previous descriptions for Fiery Topaz [Citation63].

Phaethornis a. atrimentalis Lawrence, 1858 Black-throated Hermit

As it is not easily detected inside the dense forest understory, this species may well have been more common that our observations suggest. On most evenings, one or more individuals frequently visited the flowers of a large Inga (Mimosoideae: Fabaceae) tree beside our camp, probing 5–10 flowers per visit, 2–5 m above the ground in the 15 m tall tree ((f)).

Phaethornis malaris moorei Lawrence, 1858 Great-billed Hermit (Figure )

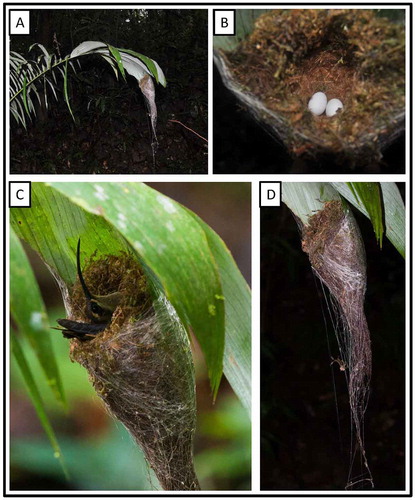

Figure 6. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. A nest of Great-billed Hermit Phaethornis malaris moorei. (A) In situ view of nest; (B) eggs inside the nest; (C) adult incubating two eggs in nest; (D) nest. Photos H. F. Greeney.

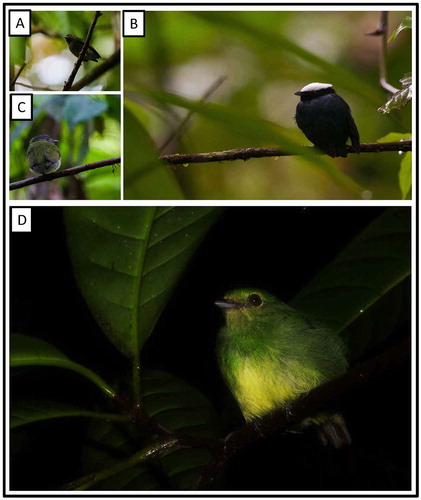

A female hermit flushed from her nest on 27 September, only after we approached to within 3 m. The nest was built in a small, swampy depression within terra firme forest, 1.5 m up on back (lower) side of a small palm frond, at the tip. It was a conical cup composed largely of green moss tightly bound with copious spider webs, with an inner lining of soft seed down, possibly balsa (Malvaceae: Bombacoideae), as is typical for this species [Citation64]. Nest measurements (cm) were: outside diameter (widest point) 9.5; outside depth (diameter front-to-back at widest point) 8; inner cup diameter (parallel to leaf) 2.7; inner diameter (front-to-back) 4.1; inner cup depth 3.6; nest overall height (length) from low point of cup to tip (also tip of supporting leaf) 13; height from back rim 16. Extending beyond the tip of the leaf, the nest had an additional 5–7 cm of sparse rootlets dangling downward. In addition, several strands of very strong spider web extended 80–110 cm from the tip of the nest, attaching it to substrates below the nest and providing a fair amount of rigidity to the nest’s location (retarding movement of the nest due to wind or arrival/departure of the adult). The nest contained two immaculate white eggs that measured 14.9 × 9.3 mm and 15.2 × 9.4 mm, and weighed 0.68 g and 0.70 g, respectively. Upon our return on 30 September, the nest still contained two eggs and the female flushed when we approached to within 2.5 m.

Heliodoxa s. schreibersii (Bourcier, 1847), Black-throated Brilliant (Figure )

Figure 7. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Black-throated Brilliant Heliodoxa s. schreibersii, adult female with nesting material; (B) Black-throated Brilliant Heliodoxa s. schreibersii, adult female (right) beside begging fledgling; (C) Black-eared Fairy Heliothryx a. auritus; (D) Glittering-throated Emerald Amazilia fimbriata fluviatilis, feeding on small flying insects swarming around Phytolacca sp. fruits at forest edge; (E) Gray-breasted Sabrewing Campylopterus largipennis aequatorialis, feeding on Inga sp. flowers at forest edge. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Figure 8. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Pavonine Quetzal Pharomachrus p. pavoninus; (B) fledgling Black-throated Trogon Trogon rufus sulphureus; (C) female Green-and-rufous Kingfisher Chloroceryle i. inda; (D) male Green Kingfisher Chloroceryle a. americana; (E) male Ringed Kingfisher Megaceryle t. torquata; (F) Yellow-billed Jacamar Galbula albirostris chalcocephala; (G) Rufous Motmot Baryphthengus m. martii; (H) Amazonian Motmot Momotus momota microstephanus. Photos H. F. Greeney.

At 1400 h, on 19 September, we observed and photographed a female Black-throated Brilliant feeding a single fledgling perched 6 m above the ground in an open vine tangle along a small ridge. Over the course of about an hour, the female changed perches several times, remaining 5–7 m above the ground and flying fairly well. Between absences of 10–15 min the female perched 1–2 m away from the fledgling, peering about and making a soft, squeaking chip note. The fledgling, in both the presence and absence of the female, also maintained a steady repetition of a similar squeaky note, repeated about every 2–5 s. Subsequently, on 25 September, at 0900 h, we observed and photographed a female Black-throated Brilliant attaching small bill-fulls of soft, pale brown tree fern ramenta to a thin (ca. 1 cm), horizontal branch. The branch was 3.2 m above the ground in a well-drained patch of terra firme forest. It was well sheltered by a fallen dead Cecropia leaf caught in the branches approximately 20 cm above the nest. We visited the nest several times during the next few days, but very little material was added. At 06:15 h on our last visit, on 30 September, the female was present and still arriving with tree fern ramenta. The nest, however, remained as little more than a thin coating of fern ramenta and spider webs on the branch. The breeding biology of Black-throated Brilliant is almost completely unknown, with no formal description of the nest and eggs [Citation65,66].

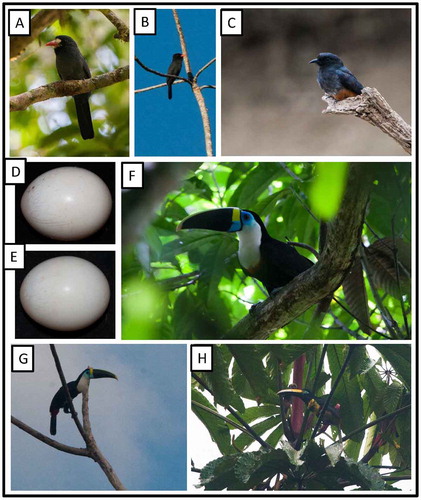

Chelidoptera t. tenebrosa (Pallas, 1782) Swallow-winged Puffbird

On 20 September, at 1415 h we flushed an adult from its nesting burrow. The nest contained two eggs but they were not inspected closely at this time. We returned on 21 September at 1715 h and took more detailed measurements after flushing the adult from the nest. The two immaculate white eggs were very fresh and showed no visible signs of embryonic development ((d) and (e)). One egg measured 25.4 × 21.2 mm and weighed 6.1 g. The second measured 25.5 × 20.8 mm and weighed 5.9 g. The entrance to the nest was in a tightly packed sandy riverbank, roughly 8 m from the edge of the water and 8 m above the current water level. The nest was excavated in a portion of the bank where it was somewhat vertical, but 1.6 m below the entrance the ground was more gently sloped. The entrance was 1 m below the top of the bank and measured 6.5 cm wide by 5 cm tall. The tunnel sloped gently downward for 1.2 m to an unlined, slightly enlarged terminal cavity. When we returned at 0815 h on 29 September the adults were not seen in the area and the nest contained only several small shell fragments. Swallow-winged Puffbirds were uncommon along all major waterways in the area, but pairs could be found fairly predictably at most locations with exposed riverbanks, presumably because they offer preferred nesting sites [Citation67–Citation71]. As is typical, we most frequently encountered them perched on the exposed ends of branches ((c)) over the river or within 20–30 m of the river edge.

Figure 9. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) White-fronted Nunbird Monasa morphoeus peruana; (B) Black-fronted Nunbird Monasa n. nigrifrons; (C) Swallow-winged Puffbird Chelidoptera t. tenebrosa; D–E) Swallow-winged Puffbird eggs; (F) Channel-billed Toucan Ramphastos vitellinus culminatus; (G) White-throated Toucan Ramphastos tucanus cuvieri; (H) Many-banded Aracari Pteroglossus pluricinctus. Photos H. F. Greeney.

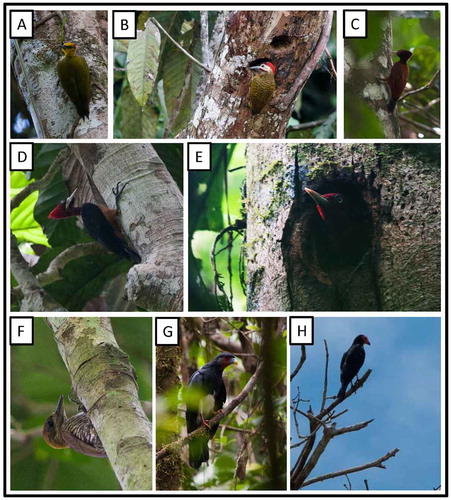

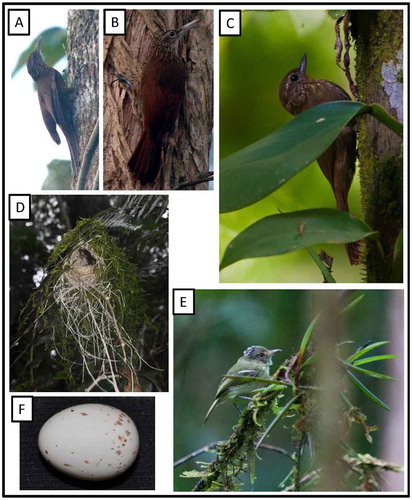

Veniliornis affinis hilaris (Cabanis & Heine, 1863) Red-stained Woodpecker

On 19 September, we encountered a pair of adults foraging through the lower canopy. They were accompanied by at least one juvenile ((f)), begging and moving through the mid-story. On several occasions, though the juvenile was out of view at the time, we detected an increase in the intensity of the begging calls and believe it was being fed by an adult.

Figure 10. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult female Yellow-throated Woodpecker Piculus flavigula magnus; (B) adult Spot-breasted Woodpecker Colaptes punctigula guttatus perched at the entrance to its nest; (C) Chestnut Woodpecker Celeus elegans citreopygius; D–E) Red-necked Woodpecker Campephilus r. rubricollis adults; (F) Juvenile Red-stained Woodpecker Veniliornis affinis hilaris; (G) Red-throated Caracara Ibycter americanus; (H) Black Caracara Daptrius ater. Photos H. F. Greeney.

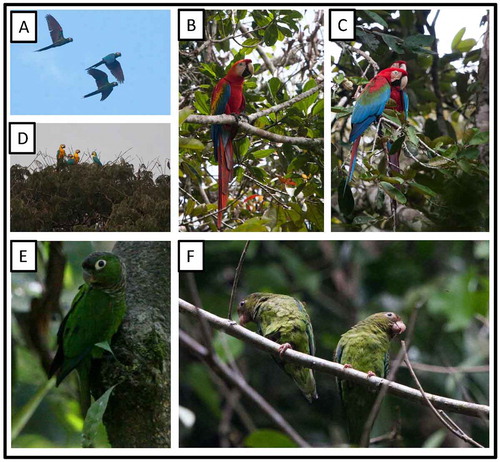

Figure 11. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Three adult Chestnut-fronted Macaws Ara severus in flight; (B) Scarlet Macaw Ara m. macao; (C) Red-and-green Macaw Ara chloropterus; (D) Blue-and-yellow Macaw Ara ararauna; (E) Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. melanura; (F) Cobalt-winged Parakeets Brotogeris c. cyanoptera. Photos H. F. Greeney.

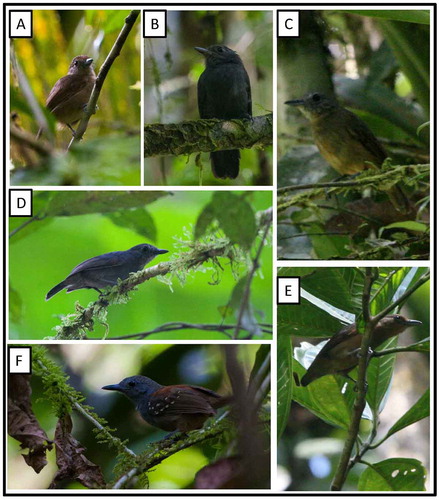

Figure 12. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) female Plain-winged Antshrike Thamnophilus schistaceus capitalis; (B) male Cinereous Antshrike Thamnomanes caesius glaucus; (C) female Dusky-throated Antshrike Thamnomanes a. ardesiacus; (D) male Dusky-throated Antshrike; (E) female Spot-winged Antshrike Pygiptila stellaris maculipennis; (F) Rufous-tailed Antwren Epinecrophylla e. erythrura. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Figure 13. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Male White-flanked Antwren Myrmotherula axillaris melaena; (B) Female Plain-throated Antwren Isleria h. hauxwelli; (C) Female Gray Antwren Myrmotherula menetriesii pallida; (D) Brown-backed Antwren Epinecrophylla fjeldsaai; (E) Male Long-winged Antwren Myrmotherula longipennis zimmeri; (F) Yellow-browed Antbird Hypocnemis h. hypoxantha; (G) Peruvian Warbling Antbird Hypocnemis peruviana saturata; (H) female White-flanked Antwren; I) Spot-winged Antbird Myrmelastes leucostigma subplumea. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Figure 14. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult female Amazonian Streaked Antwren Myrmotherula multostriata; B–C) Nest and eggs of Amazonian Streaked Antwren. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Piculus flavigula magnus (Cherrie & Reichenberger, 1921) Yellow-throated Woodpecker

On 24 September, at 10:15 h along the crest of a low ridge, we observed a pair of Yellow-throated Woodpeckers ((a)) accompanied by at least one fledgling that was actively begging for food as the family group moved through the sub-canopy. Adults returned to regurgitate food several times before they were lost from view.

Colaptes punctigula guttatus (Spix, 1824) Spot-breasted Woodpecker

On 23 September, at 07:45 h, we observed an adult female entering a cavity 5.5 m above the ground in a dead snag at the river’s edge. She was inside the cavity for only several seconds before emerging with a large fecal sac that was dropped 15–20 m from the nest as she flew away. We saw both adults entering and exiting the cavity ((b)) during the next few days but were unable to examine its contents closely. The fecal sac that we observed being removed by the female was large (roughly the size of her bill), suggesting that the nestling(s) were well grown.

Campephilus r. rubricollis (Boddaert, 1783) Red-necked Woodpecker

On 24 September, at 10:15 h, we flushed an adult ((d)) from its cavity 5 m above the ground in a tall, partially dead tree in an area of terra firme forest. During the course of the next few days, the adult continued to flush as we passed ((e)), flying away silently. On no occasion, including our last visit on 30 September, were we able to hear any movements or vocalizations from inside the cavity after the adult’s departure, suggesting that they were incubating at this time. The nest entrance was nearly circular, 10 cm in diameter, and excavated at a point where the trunk was roughly 60 cm in diameter. At this location on the trunk there was about 3 cm of living tree tissue remaining above a largely rotted core. We were unable to see into the cavity but, using a stick, determined that it extended at least 15 cm below the entrance.

Pithys albifrons peruvianus Taczanowski, 1884 White-plumed Antbird

On 26 September, at around 13:00 h we observed a group of 3–5 White-plumed Antbirds foraging with a large flock of birds attending an army ant swarm through terra firme forest. Among them was a juvenile ((b)). We did not observe it being fed by adults, and it appeared to be largely independent at this age.

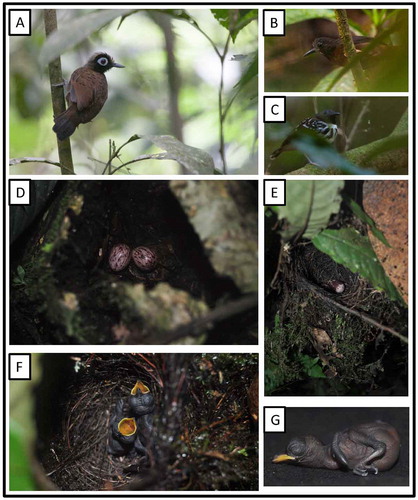

Figure 15. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult Hairy-crested Antbird Rhegmatorhina m. melanosticta; (B) Juvenile White-plumed Antbird Pithys albifrons peruvianus; (C) Adult male Spot-backed Antbird Hylophylax naevius theresae; (D) Nest and eggs of Hairy-crested Antbird; (E) Nest and egg of Spot-backed Antbird; (F) Nest and new-born nestlings of Spot-backed Antbird; (G) New-born nestling of Spot-backed Antbird. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Rhegmatorhina m. melanosticta (P. L. Sclater & Salvin, 1880) Hairy-crested Antbird

On 24 September, at 16:00 h, we encountered a nest of Hairy-crested Antbird ((a)) with two cool, undeveloped eggs. The nest was at the bottom of a vertical cavity in a hollow, 30-cm-tall stump, open from above. The cavity was roughly 15 cm in diameter and 25 cm deep. The nest was on a narrow ridgeline, 40 m above small streams on either side of the ridge. The two eggs were white with heavy cinnamon blotches and scrawls, fairly evenly distributed across most of the shell ((d)). They measured 20.9 × 16.2 mm and 20.6 × 16.2 mm and weighed 2.898 g and 2.910 g, respectively. The nest itself was a loosely compacted, poorly formed cup of dark, flexible fibers, rootlets, a few fungal rhizomorphs, bark chips, and small pieces of dead leaves. Both the nest and eggs are similar to previous descriptions [Citation72].

Hylophylax naevius theresae (Des Murs, 1856) Spot-backed Antbird (Figure (c))

On 17 September, at 15:20 h, we found a nest with two partially developed eggs, 1 m up in a 1.2-m-tall sapling growing in swampy varzea forest. The nest was a pouch-like cup of dark rootlets and fungal rhizomorphs, slung between two thin branches and with a 10–15 cm of loose material hanging below the nest. Leaves of the sapling provided some shelter from directly above the nest, also serving to hide its location from above. The eggs measured 19.2 × 13.9 mm and 18.9 × 13.8 mm and weighed 1.90 g and 1.81 g, respectively. The eggs were creamy white and well covered with dark cinnamon blotches concentrated around the widest point of the egg. On 21 September at 10:30 h and on 22 September at 10:00 h, the nest still contained two eggs. By 10:20 h on 23 September, however, both eggs had hatched ((f)). The hatchlings were blackish-skinned and bore no signs of natal down ((g)). When we returned on 30 September, the nest was empty, suggesting it had been depredated prior to fledging. We found a second nest on 25 September immediately adjacent to a small in-forest stream. The nest was 1.9 m above the ground in a 2.4-m-tall sapling, slung between two leaf petioles, one of which was 3 cm higher than the other, giving the nest a somewhat lopsided appearance. At 12:00 h the nest contained a single, well-pipped egg that would likely hatch later that day ((e)). The egg was creamy-white and heavily blotched with dark cinnamon, so much so that the markings formed a nearly continuous wreath around the widest portion of the egg. It measured 19.0 × 13.8 mm and weighed 1.68 g. Upon our return on 26 September, at 12:15 h, the egg had hatched and the nest contained a single blackish nestling, completely devoid of natal down. It weighed 1.7 g. The nests, eggs, and nestlings described here are all nearly identical to those described for this species at a nearby site in northeast Ecuador [Citation73,74].

Willisornis poecilinotus lepidonota (P. L. Sclater & Salvin, 1880) Scale-backed Antbird (Figure )

Figure 16. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. Adults, nest, and eggs of Scaled-backed Antbird Willisornis poecilinotus lepidonotus. (A) Adult male; (B) Adult female approaching nest with prey; (C) Adult male at nest; (D) Adult male approaching nest with prey (spider); (E) Newly hatched nestlings and egg shells in nest; (F) Adult female. Photos H. F. Greeney.

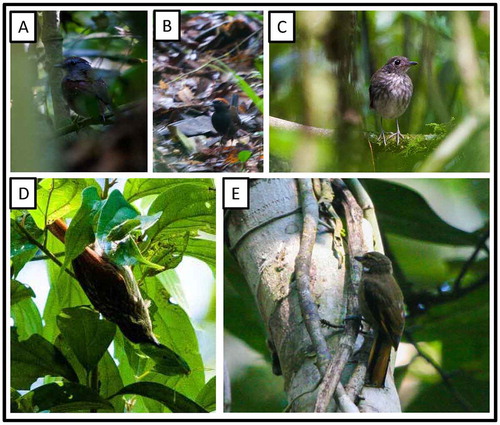

Figure 17. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult male Ash-throated Gnateater Conopophaga peruviana; (B) Rufous-capped Antthrush Formicarius colma nigrifrons; (C) Thrush-like Antpitta Myrmothera campanisona signata; (D) Chestnut-winged Hookbill Ancistrops strigilatus capturing a katydid (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae); (E) Plain Xenops Xenops minutus obsoletus. Photos H. F. Greeney.

On 21 September, at 12:00 h, we encountered male Scale-backed Antbird who performed a vigorous broken-wing display, fluttering back and forth in the leaf litter 2–3 m from us. When we returned to the area the following day, we flushed a female from the nest at 09:45 h. She flew directly from the nest and out of sight, but only after we approached to within 2 m. Fifteen minutes later we returned and the male was on the nest, but would not flush, even when we approached to within 1 m of the nest. The nest contained a newly hatched nestling and a single egg. The egg was creamy white with dark cinnamon blotching and paler cinnamon streaking, fairly evenly distributed across the shell. It measured 20.1 × 14.9 mm and weighed 2.09 g. The nestling, quite possibly having hatched that morning, was barely able to lift its head on its own. Its skin was blackish, somewhat paler pinkish-black below. The bill was dusky yellow-orange, brighter along the tomia and near the tip, which bore a dull gray egg tooth. The rictal flanges were contrastingly bright white and the mouth lining was yellow. At this time the nestling weighed 2.13 g and its right tarsus measured 7.8 mm. On 23 September we returned at 11:45 h, at which time the nest contained two nestlings. During the 15 min, we watched the nest from inside a blind positioned several meters away, the female arrived once, delivered a 2–3-mm arthropod, consumed a fecal sac produced by one of the nestlings, then departed. The male arrived shortly afterward and tried multiple times to deliver a 10–12-mm piece of a cockroach (Blattodea). After several attempts he consumed the food and settled into the nest to brood. We returned to the nest at 14:00 that day, at which point the female was brooding, flushing after we approached to within 1.5 m, but performing no broken wing display. The two nestlings weighed 2.9 g and 2.6 g, respectively. Observations on the [Citation74–Citation76].

Conopophaga aurita (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) Chestnut-belted Gnateater

Chestnut-belted Gnateater is a wide-ranging species, found through most of the Amazon Basin to eastern Brazil [Citation60,77]. In Peru, there are apparently no records west (left bank) of the Río Ucayali[Citation77], and in eastern Ecuador it is considered to be absent from south (right bank) of the Río Napo [Citation34]. There are, however, two specimens labeled as having been collected from this region and, although both are correctly identified, the accuracy of their collecting localities may be questionable [Citation77]. Greeney[Citation77] was unable to conclusively assign these two records to subspecies, but felt they best represent either C. a. occidentalis C. Chubb 1917 or, possibly C. a. inexpectata J. T. Zimmer 1931. Unfortunately, our record from Boanamo was visual only, made by DG, and the details of his sighting were not confirmed prior to his untimely death. Although our record lends weight to the presence of Chestnut-belted Gnateater south of the Río Napo, until confirmed, this record should best be considered hypothetical[Citation77].

Glyphorynchus spirurus castelnaudii Des Murs, 1855 Wedge-billed Woodcreeper

On 25 September 2012, we flushed a Wedge-billed Woodcreeper ((c)) from a nest at 08:00 h. The nest contained a single, unmarked white egg. The nest was a thick pad of coiled and interwoven black rootlets. There was no well-differentiated lining to the inner cup, but finer, unbranched rootlets and black fungal rhizomorphs predominated in the inner portion. This nest cup was built at the base (ground level) of the cavity within a 1.3-m-tall hollowed out tree trunk, entered via a natural opening 1 m from the ground, but the cavity was also accessible from the completely open top of the stump. The adult flushed from this lower entrance and flew low to the ground, disappearing from view. The nest was in mature second growth at edge of an actively farmed clearing beside the Boanamo community. We returned only once, on 26 September at 08:00 h, at which time there was no adult on the nest and it still contained only a single egg.

Figure 18. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Black-banded Woodcreeper Dendrocolaptes picumnus validus; (B) Buff-throated Woodcreeper Xiphorhynchus guttatus guttatoides; (C) Wedge-billed Woodcreeper Glyphorynchus spirurus castelnaudii; (D) Nest of Double-banded Pygmy-Tyrant Lophotriccus vitiosus affinis; (E) Adult Double-banded Pygmy-Tyrant; (F) Egg of Double-banded Pygmy-Tyrant. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Xiphorhynchus elegans ornatus J. T. Zimmer, 1934 Elegant Woodcreeper

The distribution of this woodcreeper is poorly known in Ecuador, where it is near the extreme easternmost portion of its range[Citation60] and there are only a handful of confirmed Ecuadorian records [Citation34]. Its presence in the Boanamo region, therefore, though not unexpected, is worthy of note.

Synallaxis propinqua Pelzeln, 1859 White-bellied Spinetail

This species is generally considered a bird of river islands and second-growth river edge habitats such as those dominated by Tessaria thickets and Gynerium cane along large rivers [Citation60]. In Ecuador, it is considered to be confined to the Río Napo, Río Pastaza, and lower Río Aguarico [Citation34,60]. We observed a single individual of this species, on two separate occasions, at a sharp bend in the Río Cononaco that was dominated by low, thick vegetation. Emergent above this tangled second growth were several small patches of Gynerium cane and scattered Cecropia trees. Despite the similarities of this patch of second growth to its preferred habitat, observation of this species away from large rivers is somewhat surprising. Our survey site is located roughly 30 km (straight line distance) from the Río Pastaza, and it is possible that it represents a dispersing individual. For now, however, our record may best be considered hypothetical.

Lophotriccus vitiosus affinis J. T. Zimmer, 1940 Double-banded Pygmy-Tyrant

On 23 September at 08:15 h, we flushed an adult Double-banded Pygmy-Tyrant ((e)) from a nest containing a single, partially developed egg. The egg was buffy-white with sparse, fine, cinnamon flecking ((f)), measured 16.1 × 12.2 mm, and weighed 1.3 g (weighed on 30 September). The nest was built on the underside of a fern frond near the edge of a small (ca. 20 × 30 m) natural tree-fall gap. It was 90 cm above the ground in an ear of dense fern growth and well hidden from all angles. When flushed from the nest the adult shot downward and away from the nest, remaining silent and well hidden in the dense undergrowth and traveling away from the nest for 4–6 m before flying up to an exposed perch. The nest was a loosely woven, nearly spherical ball composed almost entirely of fine, unbranched, flexible pale fibers ((d)). It had no differentiated lining but was lightly decorated on the outside with fresh green moss which made the otherwise light-colored nest fairly camouflaged. Externally, the nest was 7 cm in diameter, 9.5 cm tall, and 7.5 cm front-to-back. The small side entrance was 2.5 cm in diameter and 1.8 cm tall, and was completely covered by a frail visor-like projection above which protruded 2.5 cm from the main structure of the nest. Above the main portion of the nest, pale fibers and green moss formed an upward-oriented, conical projection, 3.5 cm in length, which attached the nest to the fern frond above. A roughly 11 cm ‘tail’ of material hung below the nest, with a few wisps of moss and long fibers hanging as low as 18 cm below the nest. Upon our return on 30 September at 17:20 h the nest still contained a single, warm egg but we were unable to monitor it further. The nesting biology of this species is very poorly known [Citation60], but the nest and egg described here agree closely with previously published descriptions [Citation78–Citation81].

Cnipodectes subbrunneus minor P. L. Sclater, 1884 Brownish Twistwing

On 18 September at 1045 h, we observed a pair of Brownish Twistwings in the vicinity of a complete, but empty, nest ((a)) hanging from the tip of a thin (0.5 cm diameter) rootlet 5.8 m above a small (2-m wide) stream within primary forest. The nest was a loose accumulation of dead leaves, long fibers and bark strips, and other dead organic material which had been twisted around the supporting rootlet. It was elongate-teardrop shaped, roughly 90 cm in overall length, with a hooded side entrance opening into a nesting chamber near the thickest portion of the nest. On one occasion an adult entered the nest with a small, thin fiber in its bill and it appeared that they were close to laying. On 27 September at 0920 h, however, the nest was fallen from the substrate but was otherwise intact. There were no signs of egg remains in the nest or surrounding area. At this time we observed one member of the pair sitting quietly on a perch 7 m above the ground, about 20 m from the fallen nest. Near this adult was the beginning of a new nest which was composed of dead leaves and fibers twisted around a hanging rootlet 1.5 m above the stream. The nest was unformed at this time, with no indication of egg-chamber formation. We detected Brownish Twistwings on only one other occasion, when we observed a pair following a large mixed-species flock through primary forest. The nesting of Brownish Twistwing remains poorly documented, with the only other report of nesting being that of Alexander Skutch [Citation82] who described an unfinished nest from Barro Colorado Island in Panama. Skutch’s nest was 2 m up, similarly attached to the tip of an aerial rootlet and appears to be similar in size, shape, and composition to the nest found here.

Figure 19. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Nest of Brownish Twistwing Cnipodectes subbrunneus minor; (B) White-eyed Tody-Tyrant Hemitriccus z. zosterops; (C) Gray-crowned Flycatcher Tolmomyias p. poliocephalus; (D) Cinnamon Manakin-Tyrant Neopipo c. cinnamomea; (E) Drab Water-Tyrant Ochthornis littoralis; (F) Olive-sided Flycatcher Contopus cooperi. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Tolmomyias assimilis obscuriceps Yellow-margined Flycatcher

At 13:00 h on 25 September, we observed an adult ((c)) carrying long, thin, dark rootlets through the subcanopy along an in-forest stream. We were not able to locate the nest.

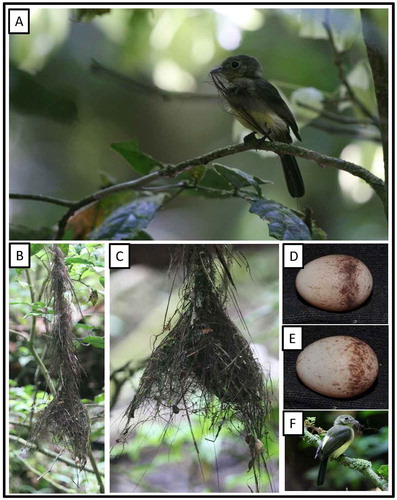

Myiobius b. barbatus (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) Sulphur-rumped Flycatcher (Figure )

Figure 20. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. Adults, nest, and eggs of Sulphur-rumped Flycatcher Myiobius b. barbatus. (A) Adult with nesting material; B–C) Nest; D–E) Eggs; (F) Adult with nesting material. Photos H. F. Greeney.

On 18 September at 13:10 h, we observed an adult perched quietly about 1 m from a nearly completed nest. As we approached it dropped a fine rootlet which it had been holding in its bill and flew silently away. The nest was empty at this time but when we returned on 27 September at 08:25 h the nest contained a single, icy-cold egg. The following day, at 16:22 h, the nest contained two eggs, both cold and showing no signs of development. The eggs were white with small cinnamon spots and flecks, heaviest near the larger end. At this time the first egg (discovered 27 September) weighed 1.6 g and the second weighed 1.4 g. They measured 16.7 × 12.3 mm and 16.4 × 12.4 mm, respectively. On 30 September at 10:10 h, the nest still contained only two eggs, both warm to the touch, but we were unable to monitor the nest further. The nest and eggs of this poorly studied species have only recently been described.

Ochthornis littoralis (Pelzeln, 1868) Drab Water-Tyrant

On 20 September, while traveling by motorized canoe down the Río Cononaco, we flushed an adult Drab Water-Tyrant ((e)) from its nest situated 3.3 m above the water level on a nearly vertical clay bank. The nest was an open cup built of long fibers and flexible strips of monocot leaves and was tucked into a small cavity on the bank, well concealed by ferns and other small herbaceous plants growing on the bank. It contained two eggs which were both showing signs of early development. They measured 18.5 × 14.7 mm and 18.5 × 15.2 mm and weighed 2.0 g and 2.2 g, respectively. Both eggs were white with small cinnamon flecks and spots. We were unable to measure the nest closely, but on 22 September the adult again flushed from the nest when our canoe passed within 5 m. These data closely agree with previous descriptions [Citation83,84].

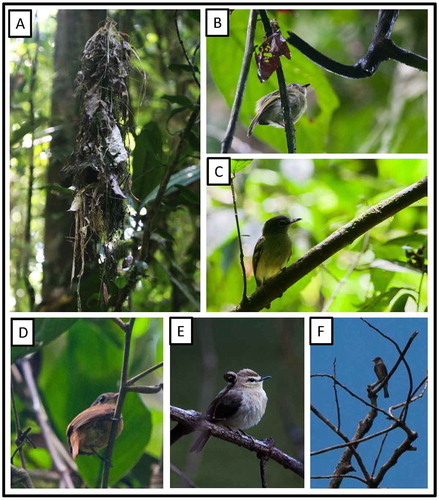

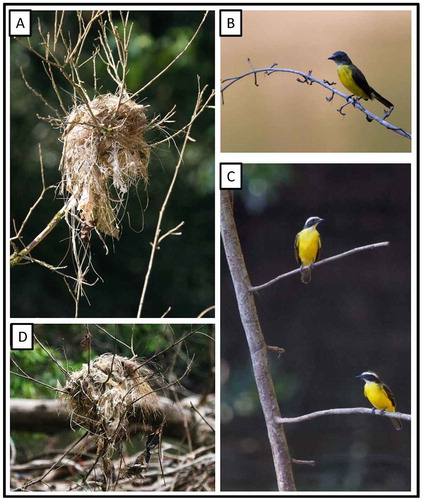

Myiozetetes s. similis (Spix, 1825) Social Flycatcher

On 16 September at 16:30 h, we observed a pair of Social Flycatchers ((c)) entering and exiting a nest placed 1.7 m above the river in an emergent snag ((a)). We were unable to access the nest, but by behavior we believe them to have been incubating.

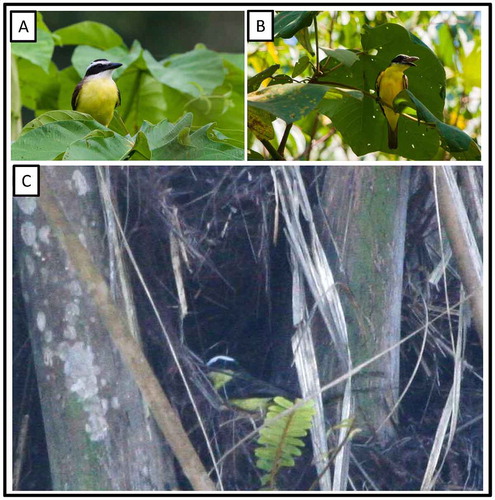

Figure 21. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Nest of Social Flycatcher Myiozetetes s. similis; (B) Adult Dusky-chested Flycatcher Myiozetetes l. luteiventris; (C) Adult Social Flycatchers perched near their nest; (D) Nest of Dusky-chested Flycatcher. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Myiozetetes l. luteiventris (P. L. Sclater, 1858) Dusky-chested Flycatcher

On 20 September at 15:00 h, we flushed an adult ((b)) from a nest built onto the top of a broken snag, roughly 15 cm in diameter at the nest, which emerged from the water of the Rio Cononaco. The nest was 3 m above the water but we were unable to examine its contents. The nest was a globular ball with a slightly downward-facing, tubular entrance. Externally, the nest was composed of large quantities of seed down (cf. Bromeliaceae) and long, thin, flexible grass inflorescences, giving it the overall appearance of naturally collected detritus left behind on the snag by receding water levels ((d)).

Pitangus s. sulphuratus (Linnaeus, 1766) Great Kiskadee

During the entire length of our stay, in a small patch of cultivated banana, papaya, and citrus, we repeatedly observed a pair of Great Kiskadees ((a)) adding material to a nearly completed nest built 2.5 m above the ground in a 4.5-m-tall Citrus sp. tree. The nest was still empty upon our departure but both adults were still in the vicinity of the nest, vocalizing and chasing each other.

Figure 22. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Great Kiskadee Pitangus s. sulphuratus; (B) Boat-billed Flycatcher Megarynchus p. pitangua; (C) Adult Three-striped Flycatcher Conopias trivirgatus berlepschi at its nest. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Conopias trivirgatus berlepschi E. Snethlage, 1914 Three-striped Flycatcher

On 19 September 2012 at 15:00 h, we found a nest of Three-striped Flycatcher under construction 15 m above the ground in a ca. 20-m-tall palm tree growing 10 m from the edge of a 1-ha patch of terra firme forest that had recently been cleared for agriculture. The nest was tucked into a natural crevice created by overlapping petiole bases where the large fronts sprouted from the top of the palm. We estimate the cavity was roughly 25 cm in diameter. It appeared that the nest would not have been completely sheltered from above, such that an adult on the nest would have been partially visible while on the nest, but we were unable to examine it closely. Both adults were in the vicinity, but only one was carrying material to the nest. During 30 min of observation, the adult arrived seven times, each time adding dead dicot leaves, strips of palm fibers, flexible rootlets, and small sticks to the nest. It remained inside the nest for only 10–20 s per visit, and was partially visible from below ((c)) as it arranged material and shaped the nest by crouching down and pressing its breast into what we presume was to be a broad, cup-shaped nest. The nesting of this species is almost completely unknown, and the nest and eggs are still to be formally described [Citation85]. The Ecuadorian distribution of Three-striped Flycatcher is poorly understood [Citation34]. Our identification was confirmed with photographic, vocal, and video evidence, providing important confirmation of its presumed presence in this area.

Tyrannus m. melancholicus Vieillot, 1819 Tropical Kingbird (Figure (c)–(h))

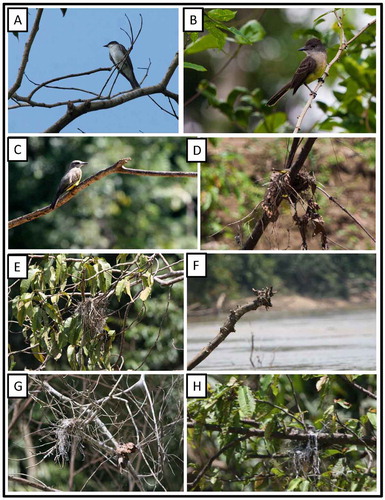

Figure 23. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus; (B) Short-crested Flycatcher Myiarchus f. ferox; (C) Adult Tropical Kingbird Tyrannus m. melancholicus; (D–H) Nests of Tropical Kingbird. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Figure 24. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult female Golden-headed Manakin Ceratopipra erythrocephala berlepschi; (B) Adult male White-crowned Manakin Dixiphia pipra discolor; (C) Female White-crowned Manakin. Photos H. F. Greeney. (D) Roosting female Blue-crowned Manakin Lepidothrix c. coronata. Photo M. Read.

During canoe trips along the Rio Cononaco, we encountered a total of five active nests of Tropical Kingbirds. At one of these, we observed an adult arriving at the nest with food, but the contents of the nest were not visible and we presume that the nestling(s) were still too small to be visible over the rim of the nest. At the other four nests we usually observed an adult sitting quietly in the nest as we passed and we presume that they were incubating or brooding small nestlings. All nests were located out over the main flow of the river and built into the small branches of dead snags. Measured from the surface of the water the five nests were 1.3, 2, 2, 7, and 5 m up.

Tyrannus tyrannus (Linnaeus, 1758) Eastern Kingbird

Single individuals of this neotropical migrant were seen perched high in the canopy during our stay. They seemed to prefer river edges and other natural or artificial gaps in the forest ((a)). On one occasion, we observed a group of 9–10 individuals perched together among the dead branches of a 10-m-tall tree beside the river.

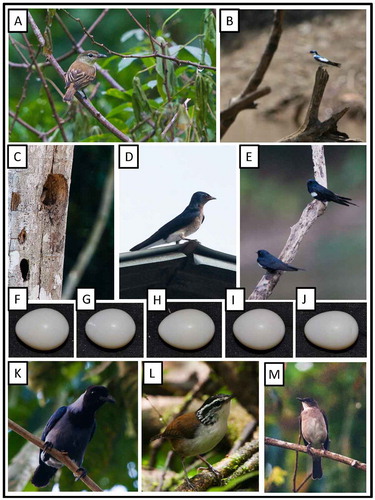

Atticora fasciata (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) White-banded Swallow (Figure (e)–(j))

Figure 25. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult female White-winged Becard Pachyramphus polychopterus tenebrosus; (B) White-winged Swallows Tachycineta albiventer; (C) Adult Gray-breasted Martin Progne c. chalybea on its nest; (D) Gray-breasted Martin; (E) White-banded Swallows Atticora fasciata; F–J) Eggs from a clutch of White-banded Swallow; K) Violaceous Jay Cyanocorax v. violaceus; L) White-breasted Wood-Wren Henicorhina leucosticta hauxwelli; M) Black-billed Thrush Turdus ignobilis debilis. Photos H. F. Greeney.

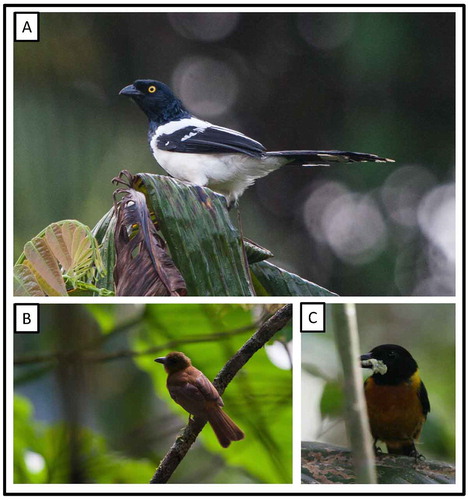

Figure 26. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult Magpie Tanager Cissopis l. leverianus; (B) Adult female Fulvous Shrike-Tanager Lanio fulvus peruvianus; (C) Adult male Fulvous Shrike-Tanager carrying prey. Photos H. F. Greeney.

At 17:00 h on 20 September 2012, we flushed an adult from a nest containing five completely undeveloped eggs. The eggs were glossy white and unmarked. The nest was 1.6 m above the current water level, tucked behind a large root partially emerged from the bank. The nest was positioned in such a way as to have portions of the nest exposed below, but the entrance and the majority of the nest were well hidden. The loose, roughly spherical nest was woven of dark rootlets, thin bark strips, and other pliable materials with an inner lining of thin, pale grass stems interwoven with dark rootlets and a few fungal rhizomorphs. It was entered through a side entrance situated in the upper portion of the spherical mass, and accessed via what appeared to be a natural opening in the bank, but which may have been slightly enlarged by the swallows themselves. We were not able to return to further examine the nest. Measurements (mm) for the five eggs were: 16.9 × 12.2, 16.6 × 13.0, 16.2 × 12.9, 16.5 × 12.9, 17.0 × 12.3.

Progne c. chalybea (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) Gray-breasted Martin

On 16 September 2012 at 13:00 h, we flushed an adult from what appeared to be a shallow cavity in a dead tree trunk emerging from the river ((c)). The excavated cavity was ca. 5 m above the water and was most likely created by a woodpecker. We were unable to examine the nest closely, but small fragments of pale grass fibers could be seen poking out from deeper inside the cavity. We found a second nest on 26 September 2012, built into the eaves of a house in the Boanamo community, ca. 4 m above the ground. At 07:30 h, we observed on adult enter the nest, while a second adult perched on the peak of the roof ((d)). After 15 min, the second adult flew from the roof, but the adult inside the nest remained, and we suggest that the nest likely contained eggs.

Henicorhina leucosticta hauxwelli Chubb, 1920 White-breasted Wood-Wren

At 09:00 h on 23 September, we encountered a pair of wrens attending at least one fledgling, fresh from the nest and still unable to fly well. The nestling remained well hidden within a tangle of fallen branches and was fed by both adults ((l)). The nesting of this species has been fairly well described [Citation87].

Tachyphonus cristatus fallax J. T. Zimmer, 1945 Flame-crested Tanager (Figure (b))

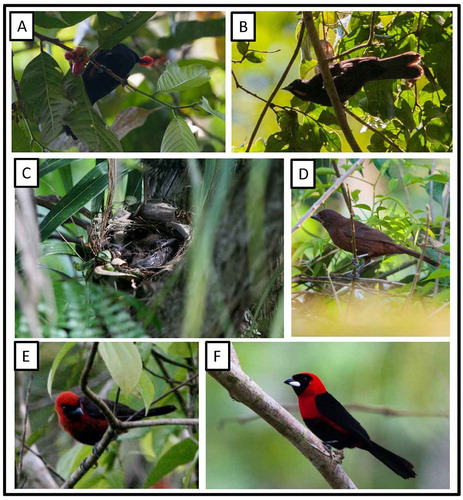

Figure 27. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult male Fulvous-crested Tanager Tachyphonus surinamus brevipes; (B) Adult male Flame-crested Tanager Tachyphonus cristatus fallax; (C) Nest and older nestlings of Silver-beaked Tanager Ramphocelus c. carbo; (D) Adult female Silver-beaked Tanager; (E) Juvenile Masked Crimson Tanager Ramphocelus nigrogularis; (F) Adult Masked Crimson Tanager. Photos H. F. Greeney.

On 17 September, we observed a female carrying a long fiber while moving with a large canopy flock at 08:00 h. We were, however, unable to locate the nest.

Lanio fulvus peruvianus Carriker, 1934 Fulvous Shrike-Tanager (Figure (b)–(c))

We found a nest of this tanager containing two small nestlings on 24 September, the details of which will be published elsewhere.

Ramphocelus nigrogularis (Spix, 1825). Masked Crimson Tanager

On 22 September, we observed an older fledgling ((e)) traveling with a pair of adults ((f)) through riverside second growth. The fledgling already wore the black mask characteristic of this species, but the remaining plumage was dull, somewhat rusty brown. It occasionally begged for food, but no food delivery by the adults, suggesting that it was close to independence. On 30 September at 06:30 h, we observed a pair of Masked Crimson Tanagers as they traveled along the forested edge of a 1-ha patch of terra firme habitat recently cleared for agriculture, approximately 1.5 km from the river’s edge. The female flew to a perch about 5 m above the ground, chipping loudly, and leaned forward while fluttering her wings and lifting her tail. The male responded by flying up and copulating briefly, after which the female flew to a nest, about 15 m away and 6 m above the ground, built into the wedge-shaped space created by the base of a palm frond that still remained attached to the trunk after leaf senescence. She immediately entered the nest, turned to face outward, and settled into the nest. After copulating, the male flew directly across the clearing, about 40-m straight line distance away, and joined a second pair of adults who were likewise foraging along the edge of the clearing. Shortly after his arrival, one of the two adults (no copulations seen) flew up to a nest carrying a long, thin pale fiber. This nest was in a nearly identical situation on the side of a palm tree, but was 15 m above the ground. The nesting biology of Masked Crimson Tanagers is poorly known, with only one full description of the nest and eggs [Citation87]. A cursory description of a nest, 1 m above the water of an oxbow lake, and a note on the dull immature plumage were also provided previously [Citation88]. Robinson [Citation89] described two nests, one 2 m above the ground and also at the base of a broken palm frond, and a second 1 m above an oxbow lake. A previously described nest [Citation87] was a mere 20 cm above the ground immediately beside an oxbow lake. The nests described here, then, considerably extend the range of nest heights used by this species, as well as suggest that palm petiole bases may be a preferred nesting site for pairs not breeding near oxbow lakes. Cooperative breeding was previously documented in Masked Crimson Tanagers [Citation89], but this is the first evidence of possible polygamy.

Ramphocelus c. carbo (Pallas, 1764) Silver-beaked Tanager

On 19 September, we observed a fledgling following a pair of adults ((d)). Its tail was already mostly grown out but its flight was still awkward and it was still being fed by its parents. On 20 September at 08:00 h, we found a nest of Silver-beaked Tanager with two well-feathered nestlings ((c)). The nest was an open cup, 1.5 m up in a tangle of small branches and large grass blades against the trunk of a spiny palm tree. Upon our return on 24 September, the nest was empty but seemed undisturbed, at 07:30 h. The nest was a compact, but somewhat loosely constructed open cup built of dead grass blades, strips of plantain leaves, black rootlets, and thin reddish-brown leaf petioles. These materials were woven together by, and the nest was attached to the substrate by, several long, living strands of a vine-like, small-leafed fern (cf. Microgramma), a material that is frequently used by this and other species of Ramphocelus [Citation87]. On the morning of 21 September, we discovered a second nest of this species, built 80 cm above the ground in a 1 m-tall sapling growing in sparse, new second growth adjacent to the river. The nest contained a single undeveloped egg at the time of discovery, but was found with broken shells inside the nest at 08:15 h on 29 September. The egg was pale blue with sparse black scrawls across the larger end and a few black spots scattered across the remainder of the shell. It was comprised of similar materials and similarly bound to the substrate by Microgramma ferns. The nesting of this species, including records of cooperative breeding [Citation89], is reasonably well documented [Citation90–Citation92].

Tangara nigrocincta (Bonaparte, 1838) Masked Tanager

At 09:00 h on 20 September, we discovered a nest of Masked Tanager built in a dense cluster of leaves re-growing from the broken trunk of an isolated tree near the center of a 1-ha patch of forest recently cleared for agriculture. The adults ((c)) were extremely wary around the nest and we were unable to determine what stage it was at, though neither adult was seen to approach the nest with food. On 24 September, the adults were less wary, and we observed both of them repeatedly entering the dense foliage with small arthropods (including lepidopteran larvae). The leaves obscured the nest and prevented us from recording details of architecture or behavior. We again saw both adults bringing food on 26 September, and on 30 September an adult was flushed from the nest at 06:00 h, suggesting it had spent the night there. This latter observation suggest that the nestlings were still quite young and we feel it is likely that hatching on or around 24 September. The nesting of this species appears almost unknown in the wild [Citation93], with no known description of its nest outside of the information provided by Miller [Citation94].

Figure 28. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Green-and-gold Tanager Tangara s. schrankii; (B) Adult male Blue Dacnis Dacnis cayana glaucogularis; (C) Masked Tanager Tangara nigrocincta; (D) Adult male Chestnut-bellied Seed-Finch Sporophila angolensis torridus; (E) Adult female Chestnut-bellied Seed-Finch; (F–G) Juvenile Chestnut-bellied Seed-Finch. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Ammodramus a. aurifrons (Spix, 1825). Yellow-browed Sparrow

On 20 September at 08:20 h, we observed a pair of Yellow-browed Sparrows ((b)) foraging on the ground at the edge of the Boanamo community, accompanied by a single, older fledgling. Both adults were bringing it food, but the fledgling also foraged on its own, appearing largely similar to adults but lacking most of the yellow feathering on the forecrown and with the tail not yet fully grown.

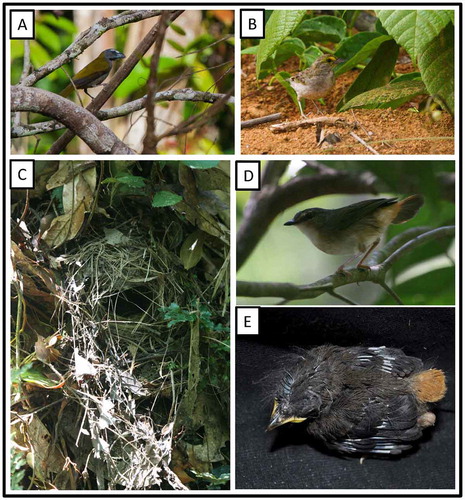

Figure 29. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Adult Buff-throated Saltator Saltator m. maximus; (B) Adult Yellow-browed Sparrow Ammodramus a. aurifrons; (C) Nest of Buff-rumped Warbler Myiothlypis f. fulvicauda; (D) Adult Buff-rumped Warbler; (E) Mid-aged nestling of Buff-rumped Warbler. Photos H. F. Greeney.

Myiothlypis f. fulvicauda (Spix, 1825). Buff-rumped Warbler (Figure (c)–(e))

On 18 September, we discovered a nest of Buff-rumped Warbler with two older nestlings. They were well feathered and their flight feathers were emerged 1–1.5 cm from their sheaths. They weighed 11.1 and 12.2 g, respectively. The nest was 50 cm up on an 80-cm high embankment formed by a well-worn mammal trail that descended down into a broad swampy area used as a salt-lick by many species. Externally, the nest was built of sticks, dicot leaves, skeletonized leaves, thin fibers, and other dead vegetative materials. Internally, skeletonized leaves and thin pale fibers predominated, concentrated particularly in the egg cup, but also extending at least partially onto the walls of the chamber. The lateral entrance was 5.5 cm wide and 3.5 cm tall. Extending outward and downward from the entrance was a broad, untidy ‘runway’ of nest material that extended 15 cm. Externally, the nest was 14 cm wide by 15 cm tall, and 13 cm from front to back. The inner chamber was 7 cm wide and 9 cm tall overall, with the egg cup being 4-cm deep measured from the lower edge of the entrance. We observed both adults bringing a variety of small arthropods to feed the nestlings. Upon our return on 27 September the nest was empty but appeared undisturbed, suggesting that the nestlings may have successfully fledged.

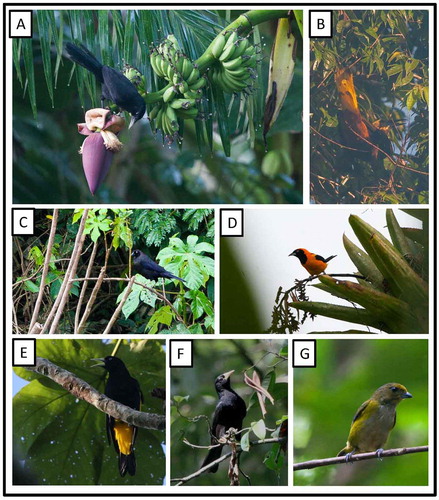

Psarocolius a. angustifrons (Spix, 1824) Russet-backed Oropendola (Figure (b))

Figure 30. Photo-documentation of avian species during the faunal inventory in the vicinity of Boanamo, Orellana Province, Ecuador, 200–270 m. (A) Solitary Black Cacique Cacicus solitarius; (B) Russet-backed Oropendola Psarocolius a. angustifrons; (C) Giant Cowbird Molothrus o. oryzivorus; (D) Orange-backed Troupial Icterus c. croconotus; (E) Yellow-rumped Cacique Cacicus c. cela; (F) Red-rumped Cacique Cacicus h. haemorrhous; (G) Female Orange-bellied Euphonia Euphonia xanthogaster brevirostris. Photos H. F. Greeney.

On 20 September, we observed several adults carrying nesting material (long, thin fibers, bark strips) to a presumed colony that was out of view across the river from the Boanamo community.

Cacicus c. cela (Linnaeus, 1758) Yellow-rumped Cacique

On 19 September 2012, we found an active colony of Yellow-rumped Caciques ((e)), with approximately 15 nests, situated 5–9 m above the ground in a ca.10-m tall tree. The tree was ca. 40 m from the forest edge, growing among the dwellings of the Boanamo community. We could see at least two small, active nests of unknown wasps (Vespidae) built among the cacique nests. There was a large amount of cacique activity, with many displaying males and most nests were appeared largely complete, but were under active construction.

Icterus c. croconotus (Wagler, 1829) Orange-backed Troupial

On of 23–28 September, we observed at least one adult enter a large, globular accumulation of material built into a clump of bromeliads 8 m above the ground on the side of tree along the river’s edge. Casual observations during daylight hours failed to reveal much activity at the nest, but on adult was frequently perched nearby ((d)) and, on 28 September 2012 at 09:30, we observed an adult emerge from the nest and depart the area with the adult that had been perched nearby. The nest was, in our opinion, very similar to those built by Thrush-like Wrens (Campylorhynchus turdinus) and, as Orange-backed Troupials are known to utilize the nests of other species [Citation95], we believe that this pair was actively incubating at the time of our observations. It remains possible, however, this nest was being used only as a dormitory.

Euphonia xanthogaster brevirostris Bonaparte, 1851 Orange-bellied Euphonia

We found a nest of this species on 22 September, at 13:30 h, at the edge of a large (0.3 ha) understory clearing created by the myrmecophilous interaction between Duroia hirsuta K. Schumann (Rubiaceae) and Myrmelachista schumanni Emery (Formicidae) [Citation96, 97]. The nest was 1.9 m above the ground and built into a clump of epiphytic Elaphoglossum ferns growing on the side of small (8 cm DBH) sapling. It contained three cool, undeveloped eggs. We observed only the female incubating. Upon our approach, while we were still more than 15 m from the nest, the female ((g)) would shoot from the nest entrance and fly swiftly and silently into the low undergrowth 10 m from the nest. The eggs were white with small cinnamon spots and flecks, denser and forming a wreath around the larger end. The nest was an ovate sphere, slightly taller than wide, built of moss and rootlets, and was entered through a hooded lateral entrance. We took no further measurements, but the form of the nest and coloration of the eggs were similar to the descriptions of previous authors [Citation83, 98, 99].

Conclusions

Our record of 362 species from this area is likely only about 60% of the actual number [Citation8,11]. Although preliminary in nature, our faunal list provides confirmation of the distributions of many species only presumed to occur in this portion of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Our record of Chestnut-belted Gnateater from this region is perhaps the most noteworthy[Citation77], but certainly requires additional confirmation. Furthermore, as both qualitative and quantitative natural history data, including reproductive seasonality, habitat use, and behavior, are crucial to the formation and testing of ecological, evolutionary, and taxonomic hypotheses, as well as the development of sound conservation plans [Citation100–Citation103], the behavioral data presented herein, provide a valuable addition to the growing body of literature dedicated to the distribution, taxonomy, natural history of Ecuador’s mainland avifauna [Citation32, 104]. In particular, we present novel nesting information for several species whose reproductive biology is particularly poorly known (e.g. Heliodoxa schreibersii, Lophotriccus vitiosus, Ramphocelus nigrogularis) [Citation60].

Author contributions

HFG and DG performed the majority of field data collection. HFG was responsible for data compilation and the majority of manuscript preparation. RPK was largely responsible for funding, permitting, and field logistics. The remaining authors contributed equally to field observations and logistical support for the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Acknowledgments

This project was completed in cooperation with Omayuhue Baihua and the Waorani Communities of Boanamo, Bameno, and Noneno. Our survey work and expedition logistics were greatly improved by all of the community members that participated in the inventory, most notably Conan Omaca, Onenka Baihua, Caiga Baihua, Bartolo Baihua, Juan Tega, Nenkeri Baihua, and Nenki Andy. This project could not have been carried out without the invaluable logistical support from Tomi Sugahara who was the project liason with the Ecuadorian government, of the Parque Nacional Yasuní director Jose Narvaez and his staff, Maria Arevalos, Edwin Carillo, Alonso Jaramillo, and Diego Naranjo. Cesar Xavier Andreade Verdesoto, Provinical Director of the Environment of the Orellana Province kindly supported our requests for research permits. We thank Kelly Swing, David Romo, Cousuelo Romo, María Rendon of the Universidad de San Francisco and the Tiputini Biodiversity Station for their support and David Lasso with the Pontifica Universidad Catolica de Ecuador and the Yasuni Biodiversity Station for his assistance. Mario Yánez and Efraín Freire, with the Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales and the Herbario Nacional were also instrumental in supporting our visit to the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve. HFG thanks Field Guides Inc., Matt Kaplan, and John V. Moore for their ongoing support of his field studies. With our deepest sympathies and sincere respect we dedicate this paper to Domingo Gualinga of the Kichwa community of Sani Isla and to Caiga Lincaye Baihua of the Waorani community of Boanamo. Domingo died from a stroke in 2015 and Caiga was speared to death in January 2016 during a violent confrontation with a neighboring indigenous group.

Associate Editor: Elisa Bonaccorso.

References

- Blake JG, Loiselle BA. Species composition of neotropical understory bird communities: local versus regional perspectives based on capture data. Biotropica. 2009;41:85–94.10.1111/btp.2008.41.issue-1

- Pitman NCA, Mogollón H, Dávila N, et al. Tree community change across 700 km of lowland amazonian forest from the Andean foothills to Brazil. Biotropica. 2008;40:525–535.10.1111/btp.2008.40.issue-5

- Rex K, Kelm DH, Wiesner K, et al. Species richness and structure of three Neotropical bat assemblages. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008;2008(94):617–629.10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01014.x

- Bass MS, Finer M, Jenkins CN, et al. Global conservation significance of Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8767.10.1371/journal.pone.0008767

- Peres CA, Terborgh JW. Amazonian nature reserves: an analysis of the defensibility status of existing conservation units and design criteria for the future. Conserv Biol. 1995;9:34–46.10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09010034.x

- Finer M, Jenkins CN, Pimm SL, et al. Oil and gas projects in the Western Amazon: threats to wilderness, biodiversity, and indigenous peoples. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e2932.10.1371/journal.pone.0002932

- Finer M, Orta-Martínez M. A second hydrocarbon boom threatens the Peruvian Amazon: trends, projections, and policy implications. Environ Res Lett. 2010;5:e014012.

- Canaday C, Rivadeneyra J. Initial effects of a petroleum operation on Amazonian birds: Terrestrial insectivores retreat. Biodiv Conserv. 2001;10:567–595.10.1023/A:1016651827287

- Pearson DL. Un estudio de las aves de Limoncocha, Provincia Napo, Ecuador. Bot Inform Cien Nac. 1972;13:3–14.

- Pearson DL, Tallman DA, Tallman EJ. The Birds of Limoncocha, Napo Province, Ecuador. Quito: Instituto Linguistico de Verano; 1972.

- Piedrahita P, Iglesias I, Tobar M, et al. Lista anotada de la avifauna en una parcela de 100 ha y en los alrededores de la estación científica Yuasuni, Parque Nacional Yasuni, Ecuador. Rev Ecuatoriana Med Cien Biol. 2012;33(1 & 2):138–157.

- English PH. Ecology of mixed-species understory flocks in Amazonian Ecuador [dissertation]. Austin (TX): University of Texas; 1998.

- Blake JG. Neotropical forest bird communities: a comparison of species richness and composition at local and regional scales. Condor. 2007;109:237–255.10.1650/0010-5422(2007)109[237:NFBCAC]2.0.CO;2

- Blake JG, Loiselle BA. Estimates of apparent survival rates for forest birds in Eastern Ecuador. Biotropica. 2008;40(4):485–493.10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00395.x

- Blake JG, Loiselle BA. Temporal and spatial patterns in abundance of the Wedge-billed Woodcreeper (Glyphorynchus spirurus) in lowland Ecuador. Wilson J Orn. 2012;124(3):436–445.10.1676/12-022.1

- Blake JG, Loiselle BA. Apparent survival rates of forest birds in Eastern Ecuador revisited: improvement in precision but no change in estimates. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e81028.10.1371/journal.pone.0081028

- Blake JG, Loiselle BA. Enigmatic declines in bird numbers in lowland forest of eastern Ecuador may be a consequence of climate change. Peer J. 2015;3:e1177.10.7717/peerj.1177

- Brooks DM, Pando-Vasquez L, Ocmin-Petit A, et al. Resource separation in a Napo-Amazonian Tinamou community. Orn Neotrop. 2004;15:323–328.

- Buitrón-Jurado G. Foraging behavior of two species, of manakins (pipridae) in mixed-species flocks in Yasuni, Ecuador. Orn Neotrop. 2008;19(2):243–253.

- Buitrón-Jurado G. Interesting distributional records of Amazonian birds from Pastaza, Ecuador. Bull Br Orn Club. 2011;131(4):241–248.

- Canaday C. Loss of insectivorous birds along a gradient of human impact in Amazonia. Biol Conserv. 1996;77(1):63–77.10.1016/0006-3207(95)00115-8

- Durães R. Lek structure and male display repertoire of blue-crowned manakins in Eastern Ecuador. Condor. 2009;111:453–461.10.1525/cond.2009.080100

- Durães R, Blake JG, Loiselle BA, et al. Vocalization activity at leks of six manakin (Pipridae) species in eastern Ecuador. Orn Neotropical. 2011;22(3):437–445.

- Ryder TB, Tori WP, Blake JG, et al. Mate choice for genetic quality: a test of the heterozygosity and compatibility hypotheses in a lek-breeding bird. Behav Ecol. 2010;21(2):203–210.10.1093/beheco/arp176

- Durães R, Loiselle BA, Blake JG. Intersexual spatial relationships in a lekking species: blue-crowned manakins and female hot spots. Behav Ecol. 2007;18(6):1029–1039.10.1093/beheco/arm072

- Greeney HF, Merino PAM. Notes on breeding birds from the Cuyabeno faunistic reserve in North Eastern Ecuador. Bol Soc Antioqueña Orn. 2006;16:46–54.

- Holbrook KM. Home range and movement patterns of Toucans: implications for seed dispersal. Biotropica. 2011;43(3):357–364.10.1111/j.1744-7429.2010.00710.x

- Ryder TB, Blake JG, Loiselle BA. A test of the environmental hotspot hypothesis for lek placement in three species of manakins (Pipridae) in Ecuador. Auk. 2006;123(1):247–258.10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[0247:ATOTEH]2.0.CO;2

- Tallman EJ, Tallman DA. The trematode fauna of an Amazonian antbird community. Auk. 1994;111(4):1006–1013.10.2307/4088836

- de Vries T, Buitrón G, Tobar M, et al. Composición, estructura, densidad y aspectos socio-ecológicos de bandadas mixtas de aves de sotobosque y dosel en una parcela de 100 ha, Parque Nacional Yasuní, Amazonia Ecuatoriana. Rev Ecuatoriana Med Cien Biol. 2012;33(1–2):88–123.

- Freile JF, Ahlman R, Brinkuizen D, et al. Rare birds in Ecuador: first annual report of the Committee of Ecuadorian Records in Ornithology (CERO). Avan Cienc Ing. 2013;5(2):B24–B41.

- Freile JF, Greeney HF, Bonaccorso E. Current neotropical ornithology: research progress 1996–2011. Condor Orn Appl. 2014;116(1):84–96.10.1650/CONDOR-12-152-R1.1

- Solano-Ugalde A, Freile JF. A decade of progress (2001–2010); overview of distributional bird records in mainland Ecuador. Orn Neotrop. 2012;23(suppl.):29–35.

- Ridgely RS, Greenfield PJ. Birds of Ecuador. Volume 1, Status, distribution, and taxonomy. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press; 2001.

- Freile JF, Mouret V, Siol M. Amidst a crowd of birds: birding Río Bigal, Ecuador. Neotrop Birding. 2015;17:47–55.

- Hollamby N. Sani Lodge: the best-kept secret in the Ecuadorian Amazon – until now. Neotrop Birding. 2012;10:69–76.

- Cadena-Ortiz H, Buitrón-Jurado G. Notes on breeding birds from the Villano River, Pastaza, Ecuador. Cotinga. 2015;37:38–42.

- Dreyer NP. A nest of Ash-throated Gnateater Conopophaga peruviana in Amazonian Ecuador. Cotinga. 2002;17:79.

- Durães R, Greeney HF, Hidalgo JR. First description of the nest and eggs of the Western striped manakin (Machaeropterus regulus striolatus), with observations on nesting behavior. Orn Neotrop. 2008;19:287–292.

- Greeney HF. A blue-crowned Manakin Lepidothrix coronata successfully defends its nest from Labidus army ants. Cotinga. 2006;25:85–86.

- Duraes R, Loiselle BA, Parker PG, et al. Female mate choice across spatial scales: influence of lek and male attributes on mating success of blue-crowned manakins. Proc Roy Soc Lond B. 2009;276:1875–1881.10.1098/rspb.2008.1752

- Greeney HF. The nest and eggs of Rusty-fronted Tody-flycatcher Poecilotriccus latirostris. Cotinga. 2014;36:59–61.

- Greeney HF. Nest and egg descriptions for two Ecuadorian puffbirds (Bucconidae). Cotinga. 2015;37:111–114.

- Greeney HF. Observations on the reproductive biology of Thrush-like Antpitta Myrmothera campanisona. Cotinga. 2017;39:84–87.

- Greeney HF, Cadena-Ortiz H. First nest description for Amazonian Trogon Trogon ramonianus, from eastern Ecuador, and a review of breeding data for Green-backed Trogon T. viridis. Cotinga. 2016;38:41–42.

- Greeney HF, Gelis RA, Garcia T, et al. The nest, eggs, and nestlings of Fulvous Antshrike Frederickena fulva from North-East Ecuador. Bull Br Orn Club. 2012;132(1):65–68.

- Greeney HF, Hualinga-L JBL, Branstein JFV, et al. Observations at a nest of the Thrush-like Antpitta Myrmothera campanisona in Eastern Ecuador. Cotinga. 2005;23:60–62.

- Ryder TB, Parker PG, Blake JG, et al. It takes two to tango: reproductive skew and social correlates of male mating success in a lek-breeding bird. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci. 2009;276(1666):2377–2384.10.1098/rspb.2009.0208

- Greeney HF, Sheldon KS. The nest and egg of Amazonian Umbrellabird Cephalopterus ornatus in the foothills of eastern Ecuador. Cotinga. 2008;29:171–172.

- Kirwan GM. Notes on the nests of five species in south-eastern Ecuador, including the first breeding data for Black-and-white Tody-Tyrant Poecilotriccus capitalis. Bull Br Orn Club. 2011;131(3):191–196.

- Greeney HF, Simbaña J, Tangila AP. Threat display and hatchling of Common Potoo Nyctibius griseus. Cotinga. 2008;29:172–173.

- Hidalgo JR, Ryder TB, Tori WP, et al. Nest architecture and placement of three manakin species in lowland Ecuador. Cotinga. 2008;29:57–61.

- Hill RI, Greeney HF. Ecuadorian birds: nesting records and egg descriptions from a lowland rainforest. Avicul Mag. 2000;106:49–53.

- Kiff LF, Marín AM, Sibley FC, et al. Notes on the nests and eggs of some Ecuadorian birds. Bull Br Orn Club. 1989;109:25–31.

- Ryder TB, Durães R, Tori WP, et al. Nest survival for two species of manakins (Pipridae) in lowland Ecuador. J Avian Biol. 2008;39:355–358.10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04290.x

- Tallman DA, Tallman EJ. Timing of breeding by antbirds (Formicariidae) in an aseasonal environment in Amazonian Ecuador. Orn Monogr. 1997;48:783–789.10.2307/40157567

- de Vries T, Melo C. First nesting record of the nest of a Slaty-Backed Forest-Falcon Micrastur mirandollei in Yasuni National Park, Ecuadorian Amazon. J Raptor Res. 2000;34:148–150.

- Remsen JV, Areta JI, Cadena CD, et al. A classification of the bird species of South America [Internet]. Philadelphia, PA: American Ornithologists’ Union; 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 17]. Available from http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.html

- del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, et al. Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive [Internet]. Barcelona; Lynx Edicions; [cited 2017 Feb 18]. Available from: http://www.hbw.com

- del Hoyo J, Collar NJ 2016. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated checklist of birds of the world, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions; 2016.

- Anderson DL. Notes on the breeding, distribution, and taxonomy of the Ocellated Poorwill (Nyctiphrynus ocellatus) in Honduras. Orn Neotrop. 2000;11:233–238.

- Lima PC, Albano C, Magalhaes ZS. Nota sobre a nidificação do bacurau-ocelado (Nyctiphrynus ocellatus) em Ituberá, Baixo Sul da Bahia. Atual Orn. 2008;143:19.

- del Hoyo J, Collar N, Kirwan GM, et al. Fiery Topaz (Topaza pyra). In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, et al., editors. Handbook of the birds of the world alive [Internet]. Barcelona; Lynx Edicions; [cited 2016 Mar 10]. Available from: http://www.hbw.com/node/467193

- Hinkelmann C, Kirwan GM, Boesman P. Straight-billed Hermit (Phaethornis bourcieri). In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, et al., editors. Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive [Internet]. Barcelona; Lynx Edicions; [cited 2016 Mar 10]. Available from: http://www.hbw.com/node/55364

- Heynen I, Boesman P, Kirwan GM. Black-throated Brilliant (Heliodoxa schreibersii). In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, et al., editors. Handbook of the birds of the world alive [Internet]. Barcelona; Lynx Edicions; [cited 2016 Mar 10]. Available from: http://www.hbw.com/node/55535

- Kirwan G. A nest of Black-throated Brilliant in October. HBW Alive Ornithological Note 28 (2015). In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, et al., editors. Handbook of the birds of the world alive [Internet]. Barcelona; Lynx Edicions; [cited 2016 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.hbw.com/node/712466

- Cherrie GK. (1916). A contribution to the ornithology of the Orinoco region. Sci Bull Mus Brooklyn Inst Arts Sci. 1916;2:133–374.

- Greeney HF, Port J. Nest architecture of the Brown Nunlet (Nonnula brunnea) and observations on the nesting of other Ecuadorian puffbird. Orn. Colomb. 2010;9:31–37.

- Haverschmidt F. Notes on the Swallow-wing, Chelidoptera tenebrosa, in Surinam. Condor. 1950;52:74–77.

- Oniki Y. Nidificação de aves em duas localidades amazônicas: sucesso e adaptações [dissertation]. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 1986.

- Skutch AF. Life history notes on puffbirds. Wilson Bull. 1948;60:81–97.

- Willson SK. First nest record of the White-throated Antbird (Gymnopithys salvini) and detailed nest records of the Hairy-crested Antbird (Rhegmatorhina melanosticta). Orn Neotrop. 2000;11:353–357.

- Greeney HF. Observations on the nesting of Spot-backed Antbird (Hylophylax naevia) in eastern Ecuador. Orn Neotrop. 2007;18:301–303.

- Greeney HF, Gelis RA. Breeding records from the North-East Andean foothills of Ecuador. Bull Br Orn Cl. 2007;2007(127):236–241.

- Pinto OMO. Sobre a colecão Carlos Estevão de peles, ninhos, e ovos de aves de Belem (Pará). Pap Avul Zool Mus Zool Univ São Paulo. 1935;11:111–222.

- Snethlage E. Beiträge zur Fortpflanzungsbiologie brasilianischer Vögel. J Orn. 1935;83:532–562.10.1007/BF01905800

- Greeney HF. Antpittas & gnateaters. London: Christopher Helm; 2018.