ABSTRACT

Platyrrhinus is a genus of leaf-nosed frugivorous bats that are endemic to the Neotropics. P. umbratus occurs in the Andean and costal mountain systems of Venezuela and Colombia. P. nigellus occurs along the Andes from Venezuela to Bolivia. Both species are medium-sized members of the genus possessing confusing taxonomic histories that have never intersected. Four of the 21 recognized species of Platyrrhinus, among them P. umbratus, do not have their taxonomic identification confirmed by molecular analyses. We provide the first genetic data (Cyt-b and ND2 sequences) for the species. Phylogenetic analyses including the new genetic data lead to the conclusion that P. umbratus and P. nigellus are conspecific. Through the use of Principal Components Analysis (PCA) and Ecological Niche Modeling (ENM), we confirm that P. umbratus and P. nigellus share high morphometric and environmental similarities. Based on such integrative approach, we regard P. nigellus as a junior synonym of P. umbratus. We provide an emended diagnosis of P. umbratus (subsuming P. nigellus) and draw morphological comparisons with other species of the genus with which it is sympatric. The conservation status of P. umbratus needs to be determined. The high rate of habitat destruction in the tropical Andes may soon cause P. umbratus to be reassigned to the Near-Threatened (NT) category of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Introduction

The genus Platyrrhinus Saussure, 1860 (Phyllostomidae: Stenodermatinae) includes 21 species of frugivorous bats that are endemic to the Neotropics [Citation1–Citation4]. Members of the genus, known as broad-nosed bats, occur from southern Mexico in the north to northern Argentina and Paraguay in the south [Citation1,Citation3–Citation5]. Platyrrhinus is one the most speciose genera of its family. Similarly to Sturnira, another speciose genus of frugivorous phyllostomids, the diversity of Platyrrhinus, peaks along the tropical Andes [Citation5–Citation8]. Members of the genus occur primarily in lowland and montane forest, from sea level to at least 3,350 m [Citation3,Citation9,Citation10].

During the past decade, studies using morphometric, morphological, and molecular analyses have improved our knowledge of the systematics and taxonomy of Platyrrhinus [Citation1–Citation5]. Of the 21 recognized species of the genus, 17 have their taxonomic identification confirmed by molecular analyses [Citation1,Citation2,Citation5]. The species for which this type of identification has not been performed are P. umbratus (Lyon, 1902), P. aquilus (Handley & Ferris, 1972), P. chocoensis (Alberico & Velasco, 1991), and P. nitelinea (Velazco & Gardner, 2009). In the case of P. aquilus and P. nitelinea, good quality tissues have not been available because all the known specimens were collected decades ago. In the case of P. umbratus and P. chocoensis, the laws regarding access to the genetic resources in most of the countries, in which these species occur, were not fully implemented until about a decade ago. This limited access to tissues needed to carry out molecular analyses [Citation11,Citation12].

Platyrrhinus umbratus occurs in the Andean and Caribbean mountain systems of Venezuela and Colombia; whereas, P. nigellus occurs along the Andes in Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia [Citation3,Citation4,Citation9,Citation10]. The taxonomic histories of both species have been riddled by confusion. P. umbratus (= Vampyrops umbratus) was described by Lyon [Citation13] based on three specimens from La Guajira department of northern Colombia [Citation3,Citation14]. In his revision of the genus, Sanborn [Citation15] synonymized P. umbratus under P. dorsalis. This treatment was followed by some authors [Citation4,Citation9,Citation16–Citation18], but others kept recognizing P. umbratus as a valid species [Citation19,Citation20]. Two taxa described by Thomas [Citation21] and Handley and Ferris [Citation22], respectively, as P. oratus (= Vampyrops oratus) and P. aquilus (= V. aquilus), have been considered as junior synonyms of either P. dorsalis [Citation4,Citation9,Citation16–Citation18] or P. umbratus [Citation19,Citation20]. A recent review [Citation3] recognized both P. umbratus and P. aquilus as valid species and regarded P. oratus as a junior synonym of P. umbratus. On the other hand, P. nigellus (= Vampyrops nigellus), which was described by Gardner and Carter [Citation23] based on specimens from central Peru, was deemed by Koopman [Citation24] to be a subspecies of P. lineatus. This treatment was maintained for more than two decades [Citation17,Citation20,Citation25–Citation27], until Velazco and Solari [Citation10] started again to treat P. lineatus and P. nigellus as different species.

Platyrrhinus umbratus and P. nigellus differ little in external and craniodental morphology. According to Velazco and Gardner [Citation3], the most important differences between them involve minor dental characters. The origin of the samples on which these comparisons were based was: P. umbratus, 177 specimens from Venezuela and Colombia; P. nigellus, 92 specimens from Venezuela and Colombia, and 211 from Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. These differences in provenance indicate that the possibility exists where intraspecific geographic variation might account for the morphological differences reported between P. umbratus and P. nigellus [Citation3]. In the present contribution, we use molecular and morphological analyses, complemented with climatic niche modeling, to determine whether the nominal species P. umbratus and P. nigellus represent a single biological species.

Methods

Our assessment of the systematics of Platyrrhinus umbratus and P. nigellus was based on analyses of sequence variation of two molecular markers, followed by an assessment of museum specimens to search for morphometric and morphological congruence with the molecular results. The acronyms of the specimens and tissues included in this study are:

| ALG | = | Field numbers of Alfred L. Gardner |

| AMNH | = | American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA. |

| BMNH | = | The Natural History Museum, London, UK (formerly British Museum of Natural History). |

| CM | = | Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. |

| CVULA | = | Colección de Vertebrados de la Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida, Venezuela. |

| FMNH | = | Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA. |

| IAvH-M | = | Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Villa de Leyva, Boyacá, Colombia. |

| ICN | = | Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. |

| LSUMZ (M) | = | Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA. |

| MCZ | = | Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. |

| MUSM | = | Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru. |

| MVZ | = | Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA. |

| ROM | = | Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. |

| TTU (TK) | = | Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, USA. |

| UAM | = | Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad de la Amazonia, Florencia, Caquetá, Colombia. |

| UMMZ | = | Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. |

| USNM | = | National Museum of Natural History (formerly U.S. National Museum), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA. |

| UV | = | Sección de Zoología, Departamento de Biología, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia. |

Molecular analysis

For five Venezuelan specimens of Platyrrhinus umbratus, we sequenced two mitochondrial genes, Cyt-b and ND2, following the protocols described by Velazco and Patterson [Citation5]. We analyzed these sequences together with those used by Velazco and Lim [Citation1], Velazco et al. [Citation2], and Velazco and Patterson [Citation5]. All sequences produced in this study were uploaded to the GenBank, with the accession numbers MH496512–MH496523 (Appendices a1). We aligned visually the sequences using CodonCode Aligner 7.0.1 (CodonCode Corporation, Dedham, MA). The Cyt-b and ND2 data sets contained, respectively, 1140 and 1044 nucleotide characters, for a total of 2184 characters. To select the models of nucleotide substitution, we used the Corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc), as determined by jModelTest 2.1.10 [Citation28]: Cyt-b (GTR+ I + Γ); ND2 (TVM+ I + Γ); and Cyt-b+ ND2 (TIM2 + I + Γ). We used PAUP* 4.0a (build 155) to calculate the intraspecific and interspecific Cyt-b uncorrected sequence divergence (“p”) [Citation29]. We conducted a maximum likelihood (ML) analysis using RAxML 8.2.10 in the CIPRES Science Gateway 3.3 [Citation30,Citation31]. We also used this software to assess support for three nodes by means of a Bootstrap resampling set to stop automatically (RAxML options: -s infile.txt -n result -p 12,345 -m GTRGAMMAI -x 12,345 -N 1000 -k -f a). Additionally, we used a Bayesian Inference (BI) analysis to estimate a phylogeny employing different models of molecular evolution for each locus. This analysis was conducted using Mr Bayes v. 3.2.6 in the CIPRES Science Gateway 3.3 [Citation31,Citation32]. Four (one cold and three heated) simultaneous Markov chains were run for 20 million generations. Trees were sampled every 1000 generations, with the first 25% of the generations discarded as “burn-in.”

Morphological analyses

We restricted morphological comparisons to P. umbratus and P. nigellus; to species closely related to P. umbratus and P. nigellus as indicated by the molecular analysis presented in this study (P. aurarius, P. dorsalis, P. ismaeli, P. masu); and to species lacking molecular data but similar in size to P. umbratus and P. nigellus (P. aquilus, P. chocoensis). To ascertain the congruence of phenotypic and genetic characters, we grouped museum specimens (P. umbratus, P. nigellus) for morphological and morphometric analyses based on the results of the molecular analysis (Appendices a2). External and osteological characters were based on, but not restricted to, those defined by Velazco and Gardner [Citation3], Velazco [Citation4], and Velazco and Solari [Citation10]. The terminology for the dental homology of premolars follows Velazco [Citation4]: first upper premolar (P3), second upper premolar (P4), first lower premolar (p2), and second lower premolar (p4).

Morphometric analysis

Based on the presence of closed epiphyses in wing digits, we verified all the specimens to be adults (for a list of the specimens examined, refer to Appendices a2). We used a digital caliper with a 0.01 mm accuracy to record one external (forearm) and 21 craniodental measurements. Craniodental measurements are the same illustrated by Velazco and Gardner [3, ]. Their description and abbreviations are as follows:

Figure 1. Maximum-likelihood phylogram for Platyrrhinus species. Support statistics from the ML and Bayesian analyses are indicated at each resolved node: Bayesian posterior probabilities/ML bootstrap frequencies (values greater that 50% are presented).

Greatest length of skull (GLS), distance from the posterior-most point of the occiput to the anterior-most point of the premaxilla (excluding incisors).

Condyloincisive length (CIL), distance between a line connecting the posterior-most margins of the occipital condyles and the anterior-most surface of the upper incisors.

Condylocanine length (CCL), distance between a line connecting the posterior-most margins of the occipital condyles and a line connecting the anterior-most surface of the upper canines.

Braincase breadth (BB), greatest breadth of the braincase, excluding the mastoid and paraoccipital processes.

Zygomatic breadth (ZB), greatest breadth across the zygomatic arches.

Postorbital breadth (PB), breadth at the postorbital constriction.

Palatal width at canines (C-C), least width across palate between the cingula of the upper canines.

Mastoid breadth (MB), greatest breadth across the mastoid region.

Palatal length (PL), distance from the posterior palatal notch to the anterior border of the incisive alveolus.

Maxillary toothrow length (MTRL), distance from the anterior-most edge of the upper canine crown to the posterior-most edge of the crown on M3.

Molariform toothrow length (MLTRL), posterior border of the M3 alveolus to the anterior border of P3.

Width at M1 (M1-M1), greatest width of palate across M1-M1.

Width at M2 (M2-M2), greatest width of palate across M2-M2.

Maxillary breadth (MXBR), least width across the maxilla, from the lingual sides of the two M2.

M1 width (M1W), greatest width of crown.

M2 width (M2W), greatest width of crown.

Dentary length (DENL), from the posterior-most point of the mandibular condyle to the anterior-most point of the dentary.

Mandibulary toothrow length (MANDL), distance from the anterior-most surface of the lower canine to the posterior-most surface of m3.

Coronoid height (COH), perpendicular height from the ventral surface of the mandible to tip of the coronoid process.

Width at mandibular condyles (WMC), greatest width between the inner margins of the mandibular condyles.

Width of m1 (m1W), greatest width of crown.

To achieve normalization for statistical analyses, all measurements were log-transformed. We evaluated morphometric differences between populations of Platyrrhinus nigellus and P. umbratus, and between sexes of both species, by means of a PCA based on the variance–covariance matrix. We retained components with eigenvalues greater than 1. To show the relationships between groups in the morphospace, we plotted the principal component (PC) scores. For these procedures, we used PAST v3.14 [Citation33].

Ecological niche modeling

Data input

We used ENM [Citation34] to explore the environmental similarity between P. umbratus and P. nigellus. We created a niche model for each nominal species separately, and a pooled model by including all occurrence records for both species into a single data set (Appendices a3). These analyses were based exclusively on data from voucher specimens on deposit in natural history museums, with their taxonomic identifications confirmed via morphology. We carefully geo-referenced the collection localities of specimens lacking field GPS readings in their tag data. To reduce sampling bias [Citation35], we spatially thinned our original data set using the spthin package in R [Citation36]. While retaining the greatest number of localities possible, thinning ensured that the distance between all pairs of localities exceeds 10 km.

As potential predictors of the species’ climatic niches, we chose six bioclimatic variables from the WorldClim data set, with a resolution of ca. 1 km2 at the equator. These variables reflect information pertaining to temperature and rainfall [Citation37]. Taking into account the known elevational distribution of P. umbratus and P. nigellus, we chose six climatic predictors known to impose physiological constraints on montane mammals [Citation38]: BIO 01 (annual mean temperature), BIO 05 (maximum temperature of warmest month), BIO 06 (minimum temperature of coldest month), BIO 12 (annual precipitation), BIO 13 (precipitation of wettest month), and BIO 14 (precipitation of driest month). We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for every pairwise comparison of variables across the study area using ENMTools [Citation39].

Model calibration and evaluation

Niche models were built using a maximum entropy method (Maxent [Citation40]), which uses localities of known presence and a random sample of pixels from the study region (i.e. background points) to characterize the environments preferred by species [Citation35]. To be used as the calibration area of niche models, we delimited the study area to a buffer of three degrees encompassing all records, excluding areas that are unlikely to be accessible for P. umbratus and P. nigellus owing to limits in their dispersal capabilities [Citation41]. To acquire a relatively good representation of environments available for these species, we included 100,000 random pixels within the delimited study area.

We calibrated and projected the niche models across the study areas corresponding to the three target taxa (P. umbratus, P. nigellus, and P. umbratus + nigellus). Because this involved transferring the niche models into a different space from that used for model calibration, we performed a Multivariate Environmental Similarity Surfaces (MESS) Analysis to quantify the similarity between the calibration and transference regions [Citation42].

To select model settings approximating optimal levels of complexity, we constructed models with a wide variety of different combinations of feature classes (FC: Linear; Quadratic; Linear and Quadratic; Hinge; Linear, Quadratic, and Hinge) and regularization multipliers (RM: 1.0–6.0). We evaluated the models in the ENMeval package in R [Citation43]. We applied a spatial block approach to data partitioning to obtain model evaluation statistics. To select optimal settings, we inspected threshold-dependent (omission rate for testing points, or OR10, using a threshold set by the 10% training omission rate) and threshold-independent (AUC for testing points, or AUCTEST) evaluation statistics.

We kept continuous suitability values to indicate successively higher suitability, from 0 (lowest suitability) to 1 (highest suitability). To determine the similarity among the three model outputs (P. umbratus, P. nigellus, and P. umbratus + nigellus), we used the Schoener’s D metric, which varies from 0 (no niche overlap) to 1 (full niche overlap). To facilitate interpretation, we categorized D values as follows [Citation44]: no or very limited overlap (0–0.2); low overlap (0.2–0.4); moderate overlap (0.4–0.6); high overlap (0.6–0.8); and very high overlap (0.8–1.0).

Results

Molecular analyses

ML and BI analyses of the combined mitochondrial markers (2184 bp) produced similar highly supported topologies (). Four of the five Venezuelan specimens of Platyrrhinus umbratus were recovered forming a clade sister to the clade containing the five Peruvian specimens of P. nigellus. However, the fifth Venezuelan specimen of P. umbratus nested within the Peruvian P. nigellus, indicating the presence of polyphyly in the P. nigellus clade (). As in Velazco and Patterson [Citation3], P. nigellus was recovered as sister to the P. ismaeli + P. masu clade (). The average Cyt-b pairwise distance among the specimens of P. nigellus + P. umbratus is 0.70%. The average pairwise distance between P. nigellus + P. umbratus and the closely related species P. ismaeli and P. masu is, respectively, 4.7% and 4.3% ().

Table 1. Pairwise uncorrected (%) divergences (mean ± standard deviation) in Cyt-b sequences among six Platyrrhinus species.

Morphometric analysis

We compared a sample (n = 42) of Platyrrhinus umbratus from Colombia and Venezuela with a sample of (n = 56) of P. nigellus from Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. We combined both samples into a single one, and performed a PCA to compare morphometrically both nominal species, and males with females irrespective of nominal species. The first three PCs accounted for 74.2% (PC1, 50.4%; PC2, 15.0%) of the total variance. A plot of the scores on the two first PCs () showed a high overlap between P. nigellus and P. umbratus, indicating both nominal species to be similar in size and shape (). Another plot of the scores on the two first PCs () showed a high overlap between males and females, indicating secondary sexual dimorphism in size and shape to be absent or nearly absent in P. nigellus + P. umbratus ().

Table 2. Factor loadings for the first three factors extracted from the correlation matrix in a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 22 measurements comparing Platyrrhinus umbratus and P. nigellus.

Ecological niche modeling

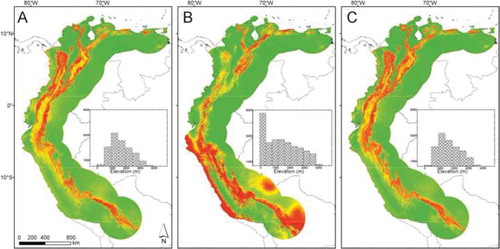

In terms of overfitting and discrimination, the pool of optimal settings that we selected showed a high performance for the three (Platyrrhinus umbratus, LQ1; P. nigellus, LQH4; P. nigellus + P. umbratus, LQH4) models (). Pearson correlation coefficients indicated that BIO 05 and BIO 12 were the variables most highly correlated with each other (> 0.9); however, by looking at the lambda values we noticed that these two variables were not included in the final Maxent models. The final models applying these optimal settings yielded ecologically realistic current predictions that showed a tight association with the distribution of montane forest in the northern Andes and the mountains of northern Venezuela. The predictions for current climatic conditions for the three models showed clear qualitative similarities in geographic space (). For P. umbratus, the prediction was tight and less-diffuse for Colombia and Venezuela, but relatively widespread for the lowlands and coastal region from the southern part of the study area (). For P. nigellus and P. nigellus + P. umbratus, the highest suitability scores of the models corresponded to mountain forests above 500 m ( and ). For the three models, some montane areas in northeastern Colombia and northern Venezuela were clearly separated by less-suitable lowland areas, with environments representing potential barriers to the dispersal of P. umbratus + P. nigellus.

Table 3. Evaluation metrics of ecological niche models generated for the broad-nosed bats, Platyrrhinus umbratus and P. nigellus, in northern South America. FC, feature classes; RM, regularization multiplier; AUCTEST, threshold-independent metric based on predicted values for the test localities; OR10, threshold-dependent metric indicating the proportion of test localities with suitability values lower than that excluding the 10% of training localities with the lowest predicted suitability; p, number of parameters in the model; EXVAR, variables excluded from the final model.

Figure 3. Estimation of current potential distributions for broad-nosed bats in northern South America. Maxent models based on: A) Platyrrhinus nigellus occurrences; B) P. umbratus occurrences; C) P. nigellus + P. umbratus occurrences. Increasingly warm colors indicate higher suitability values across the study area. Histograms, showing elevation range and pixel frequency of predicted potential distributions, are inserted in the maps.

The potential distributions of Platyrrhinus umbratus and P. nigellus in the geographic space were highly similar (D = 0.707), suggesting both nominal species to possess broadly overlapping climatic niches. Comparison of the potential distributions of P. umbratus and P. umbratus + P. nigellus (D = 0.669), and P. nigellus and P. umbratus + P. nigellus (D = 0.936), also suggested broadly overlapping climatic niches. The MESS analysis showed non-analogous conditions in a small region of the projection area for the P. umbratus model, indicating that the prediction for areas in the southernmost region of the potential distribution should be considered with caution.

Systematics

Platyrrhinus umbratus (Lyon, 1902)

Shadowy broad-nosed bat

Synonyms:

Vampyrops lineatus: Bangs, 1900:100; not Phyllostoma lineatum Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, 1810.

Vampyrops umbratus Lyon, 1902:151–152; type locality “San Miguel,” La Guajira, Colombia.

Vampyrops oratus Thomas, 1914:411–412; type locality “Galifari, Sierra del Avila, [Distrito Federal,] N. Venezuela. Alt. 6500ʹ” [which we emend to “Galipán (10°33′N, 66°54′W, 1,980 m), Cerro Ávila, 5.7 km NE Caracas, Vargas, Venezuela”].

Vampyrops nigellus Gardner and Carter, 1972a:1; type locality “Huanhuachayo (12°44′S, 73°47′W), about 1660 m, Departamento de Ayacucho, Peru.”

Vampyrops lineatus nigellus: Koopman, 1978:11; new name combination.

Platyrrhinus umbratus: Koopman, 1993:191; first use of current name combination.

P[latyrrhinus]. lineatus nigellus: Anderson, 1997:12; new name combination.

P[latyrrhinus]. nigellus: Velazco and Solari, 2003:303; first use of current name combination.

Holotype

Study skin and skull of an adult female, Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ B8180), collected on 8 June 1898 by W. W. Brown, Jr. (original field number: 234). Skin and skull in good condition, with the exception of the proximal portions of the forearms were removed during preparation. The exact location of the type locality of P. umbratus has been the matter of confusion owing to vague information on the provenance of the specimens [Citation13,Citation45]. Some researchers place it in the Magdalena Department [Citation9,Citation19]. The MCZ collections place it in the Santander Department. Others place it in the La Guajira Department [Citation14]. Currently, it is accepted that the type locality of P. umbratus is in the La Guajira Department, as stated by Helgen and MacFadden [Citation14] and followed by Velazco and Gardner [Citation3].

Measurements of the holotype

MCZ B8180: GLS, 26.3; CIL, 24.6; CCL, 24.0; BB, 11.2; ZB, 15.4; PB, 6.4; C–C, 6.8; MB, 12.2; PL, 13.4; MTRL, 10.3; MLTRL, 8.6; M1–M1, 11.0; M2–M2, 11.0; MXBR, 6.9; M1W, 2.1; M2W, 2.5; DENL, 18.4; MANDL, 11.0; COH, 6.0; WMC, 7.5; m1W, 1.9; FA, [44.1].

Distribution

Platyrrhinus umbratus is found in northern Venezuela and northern Colombia, south through Ecuador and Peru to south-central Bolivia (). The species can sometimes be found in lowland habitats, but is mainly found at intermediate and high elevations (between 400 and 3,150) in the tropical Andes, and in the coastal mountain systems of Venezuela.

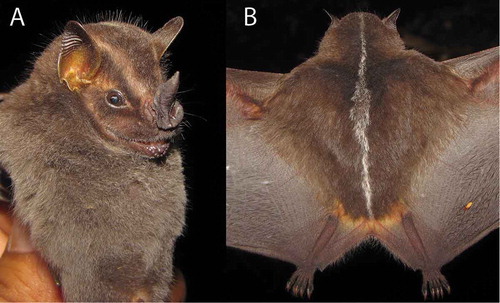

Emended diagnosis

Platyrrhinus umbratus is a medium-sized bat (FA 40–48 mm, GLS 23.8–27.0 mm, CCL 21.5–26.3 mm; , ). The species is most easily distinguished from P. aquilus, P. aurarius, and P. ismaeli by its shorter skull (). Most of the measurements of P. umbratus overlap those of P. chocoensis, P. dorsalis, and P. masu (). With respect to these species, P. umbratus can be diagnosed by the following combination of characters: 1) facial stripes well marked but dusky (); 2) dorsal stripe conspicuous but narrow (); 3) dorsal and ventral fur pale brown to blackish (); 4) ventral fur possessing three color bands; 5) fringe of uropatagium covered with long (> 3.5 mm) and dense hair, paler than that of dorsum (); 6) upper surface of feet covered by long (> 4 mm) and dense hair; 7) fold lines in pinnae well marked (); 8) noseleaf surrounded by six or seven vibrissae; 9) basal protuberance at the point of implantation of genal vibrissae absent; 10) one interramal vibrissa; 11) metacarpal III shorter than metacarpal V; 12 and 13) paraoccipital and postorbital processes moderately developed; 14) squamosal end of the zygomatic arch possessing a moderately developed fossa laterally to the glenoid fossa; 15) upper inner incisors monolobed and in contact; and 16 and 17) M1 lacking a parastyle, and possessing a moderately to well developed protocone.

Table 4. External and cranial measurements (mm) of Platyrrhinus umbratus. Values stand for: mean (minimum–maximum) sample size.

Comparisons

Platyrrhinus umbratus is sympatric with P. albericoi, P. chocoensis, P. dorsalis, P. infuscus, P. ismaeli, P. masu, and P. vittatus. P. umbratus is easily distinguished from P. albericoi, P. infuscus, P. ismaeli, and P. vittatus by its shorter forearm and skull (; Velazco and Gardner [Citation3]: , ).

Platyrrhinus umbratus has been confused with P. dorsalis and overlaps in measurements with P. chocoensis and P. masu (; Velazco and Gardner [Citation3], , ). Therefore, the following comparisons are focused on differentiating P. umbratus from P. chocoensis, P. dorsalis, and P. masu.

External characters distinguishing P. umbratus are: 1) long (> 8 mm) dorsal hair, as opposed to short (< 8 mm) hair in P. chocoensis and P. masu; 2) upper surface of the feet covered by long (> 2.5 mm) and dense hair, as opposed to short (< 2 mm) and moderately dense in P. chocoensis and P. dorsalis; 3) ventral hairs possessing three color bands, as opposed to two bands in P. chocoensis; 4) uropatagial fringe covered by long (> 4 mm) and dense hair, as opposed to short and sparse hair in P. chocoensis and P. dorsalis; 5) well-marked fold lines in the pinnae, as opposed to poorly marked in P. dorsalis; 6) metacarpal III shorter than metacarpal V, as opposed to subequal in P. chocoensis and P. dorsalis.

Dental characters distinguishing P. umbratus are: 1) lingual cingulid of p4 present, as opposed to absent in P. chocoensis; 2) well-developed protocone on M1, as opposed to small and blunt in P. dorsalis and P. chocoensis; 3) lack of a stylar cuspule on lingual face of M2, as opposed to present in P. dorsalis; 4) lingual cingulum of M2 metacone not extending beyond the metacone, as oposed to continuous to paracone in P. chocoensis and P. dorsalis.

Discussion

By regarding Platyrrhinus nigellus as a junior synonym of P. umbratus, we reduce the number of recognized species of Platyrrhinus to 20. Despite their complex taxonomic histories, the synonymies of P. umbratus and P. nigellus have never intersected. For over half a century since its description by Lyon [Citation13], P. umbratus was considered as valid species. This changed when Sanborn [Citation15], in his review of the genus Vampyrops (= Platyrrhinus), regarded P. umbratus as a junior synonym of dorsalis, an arrangement that was followed in a review of the Peruvian species of the genus [Citation16]. More than two decades after Sanborn [Citation15], Handley [Citation46] resurrected P. umbratus as a valid species. However, P. umbratus continued to be regarded as a synonym of P. dorsalis for three decades [Citation4,Citation9,Citation17], Thereafter, Handley’s [Citation46] view gained acceptance, and P. umbratus was again recognized as a valid species [Citation3,Citation19,Citation20].

Platyrrhinus nigellus was described in 1972 [Citation23]. It was deemed to be a junior synonym of P. lineatus [Citation19,Citation26,Citation47–Citation51] or a subspecies of P. lineatus [Citation20,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27]. More than three decades after its description, based on morphological and morphometric analyses, Velazco and Solari [Citation10] and Velazco [Citation4], showed P. nigellus to be a valid species distinct from P. lineatus.

Two morphological-phylogenetic analyses have included both Platyrrhinus umbratus and P. nigellus as study taxa. Owen [Citation52] found P. nigellus to be related to three small species (P. brachycephalus, P. helleri, P. recifinus), and P. umbratus to two large species (P. aurarius, P. vittatus). Velazco and Gardner [Citation3] found both P. umbratus and P. nigellus to belong to a clade composed of the medium to large species of Platyrrhinus: P. umbratus was recovered as sister to P. chocoensis and P. nigellus as sister to a clade composed of nine species (P. albericoi, P. chocoensis, P. dorsalis, P. infuscus, P. ismaeli, P. masu, P. nitelinea, P. umbratus, and P. vittatus).

Sequences of P. umbratus were not available for the only published molecular-phylogenetic analysis, based on four genetic markers (Cyt-b, ND2, D-loop, RAG2) [Citation5]. This analysis found P. nigellus to be sister to a clade containing P. ismaeli + P. masu. Our addition of Cyt-b and ND2 sequences from P. umbratus to the Cyt-b and ND2 published sequences [Citation5], led to a topology () similar to that based on the four genetic markers [Citation5]: P. umbratus + P. nigellus were united in a clade sister to the P. ismaeli + P. masu clade.

The fast-evolving nature of mitochondrial genes allows them to be widely used to infer relationships among phyllostomid bats and to reveal hidden diversity or the need of synonymyzation (e.g. [Citation5,Citation7,Citation53–Citation57]). In contrast, the slow-evolving nature of nuclear genes hinders their use in a similar manner, as shown by the failure to recover clades and/or species supported by mitochondrial genes and morphology [Citation5,Citation7]. Based on genetic distance values found to distinguish other species of Platyrrhinus and species in other phyllostomid genera [Citation1,Citation2,Citation5,Citation7,Citation53], the low divergence (0.70%) among the Cyt-b sequences of the P. umbratus + P. nigellus specimens suggests that both nominal species should be synonymized into a single species, whose valid name should be P. umbratus by application of the Principle of Priority of zoological nomenclature. This course of action is further supported by the finding that one specimen of P. umbratus was nested within the P. nigellus clade (). This synonymization is also supported by our morphometric analysis: the PCA plot () showed a major overlap in size and shape between specimens assigned to both species. Finally, the climatic niche of the two nominal species is highly similar, which suggests that there is no ecological differentiation.

Given that four of the five Venezuelan specimens are in a clade, and that the five Peruvian specimens are in another clade (), some kind of geographic structure may be present in P. umbratus, as it might be expected for a species with such an ample geographic distribution.

As part of the most recent IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Global Mammal Assessment [Citation58,Citation59], P. umbratus was listed in the Data Deficient (DD) category [Citation60] owing to the absence of up-to-date information on its extent of occurrence, threats, status, and ecological requirements; whereas, P. nigellus was listed in the Least Concern (LC) category [Citation60] based on its wide distribution and presumed large population, and because it is unlikely to be declining at nearly the rate required to qualify for listing in a threatened category. The conservation status of P. umbratus (subsuming P. nigellus) needs to be determined. The high rate of habitat destruction throughout the tropical Andes may soon cause P. umbratus to be reassigned to the NT category [Citation60].

Associate Editor: Elisa Bonaccorso

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Velazco PM, Lim BK. A new species of broad-nosed bat Platyrrhinus Saussure, 1860 (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) from the Guianan Shield. Zootaxa. 2014;3796(1):175–193.

- Velazco PM, Gardner AL, Patterson BD. Systematics of the Platyrrhinus helleri species complex (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae), with descriptions of two new species. Zool J Linn Soc. 2010;159(3):785–812.

- Velazco PM, Gardner A. A new species of Platyrrhinus (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) from western Colombia and Ecuador, with emended diagnoses of P. aquilus, P. dorsalis, and P. umbratus. Proc Biol Soc Wash. 2009;122(3):249–281.

- Velazco PM. Morphological phylogeny of the bat genus Platyrrhinus Saussure, 1860 (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) with the description of four new species. Fieldiana Zool. 2005;105:1–53. New Series.

- Velazco PM, Patterson BD. Phylogenetics and biogeography of the broad-nosed bats, genus Platyrrhinus (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;49(3):749–759.

- Velazco PM, Patterson BD. Two new species of yellow-shouldered bats, genus Sturnira Gray, 1842 (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae) from Costa Rica, Panama and western Ecuador. ZooKeys. 2014;402:43–66.

- Velazco PM, Patterson BD. Diversification of the yellow-shouldered bats, genus Sturnira (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae), in the New World tropics. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;68:683–698.

- Molinari J, Bustos XE, Burneo SF, et al. A new polytypic species of yellow-shouldered bats, genus Sturnira (Mammalia: chiroptera: phyllostomidae), from the Andean and coastal mountain systems of Venezuela and Colombia. Zootaxa. 2017;4243:75–96.

- Gardner AL. Genus Platyrrhinus Saussure, 1860. Gardner AL, editor. Mammals of South America, Volume 1: marsupials, Xenarthrans, Sherws, and Bats. Vol. I. Chicago: university of Chicago Press; 2008. 329–342. Copyright 2007; published March 2008.

- Velazco PM, Solari S. Taxonomía de Platyrrhinus dorsalis y Platyrrhinus lineatus (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) en Perú. Mastozoologia Neotropical. 2003;10:303–319.

- Ferreira-Miani P., et al. Colombia: access and exchange of genetic resources. In: Carrizosa S, Brusch SB, Wright BD, editors. Accessing Biodiversity and Sharing the Benefits: lessons from Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Gland. Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN; 2004. p. 79–100.

- Chaves J. The Andean pact and traditional environmental knowledge. In: Stoianoff NP, editor. Accessing biological resources: complying with the convention on biological diversity. The Hague, The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International; 2004. p. 223–260.

- Lyon JMW Description of a new bat from Colombia. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 1902;15:151–152.

- Helgen KM, McFadden TL. Type specimens of recent mammals in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Bull Museum Comp Zool. 2001;157(2):93–181.

- Sanborn CC. Remarks on the bats of the genus Vampyrops. Fieldiana: Zool. 1955;37(14):403–413.

- Gardner AL, Carter DC. A review of the Peruvian species of Vampyrops (Chiroptera: phyllostomatidae). J Mammal. 1972;53:72–82.

- Alberico M. Systematics and distribution of the genus Vampyrops (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) in northwestern South America. In: Peters G, Hutterer R, editors. Vertebrates in the Tropics: proceedings of the International Symposium on Vertebrate Biogeography and Systematics in the Tropics. Bonn: Alexander Koenig Zoological Research Institute and Zoological Museum; 1990. p. 103–111.

- Carter DC, Rouk CS. Status of recently described species of Vampyrops (Chiroptera: phyllostomatidae). J Mammal. 1973;54:975–977.

- Simmons NB. Order Chiroptera. In: Wilson DE, Reeder DM, editors. Mammal species of the world, a taxonomic and geographic reference. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. p. 312–529.

- Koopman KF. Chiroptera: systematics. Handb Zool VIII (Mammalia). 1994;60:1–217.

- Thomas O. Four new small mammals from Venezuela. Ann Magazine Nat Hist. 1914;14(series 8):410–414.

- Jr CO H, Ferris KC Description of new bats of the genus Vampyrops. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 1972;84:519–524.

- Gardner AL, Carter DC A new stenodermine bat (Phyllostomatidae) from Peru. Occasional Papers of the Museum, Texas Tech University. 1972;2:1–4.

- Koopman KF. Zoogeography of Peruvian bats with special emphasis on the role of the Andes. A Muse Novitates. 1978;2651:1–33.

- Anderson S. Mammals of Bolivia: taxonomy and distribution. Bull Am Museum Nat Hist. 1997;231:1–652.

- Koopman KF. Order Chiroptera. Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference. 2nd revised ed. Washington & London: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1993. p. 137–241.

- Willig M, Hollander R. Vampyrops lineatus. Mammalian Species. 1987;275:1–4.

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, et al. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9(8):772.

- Swofford DL. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and other methods). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates; 2002.

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–1313.

- Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T, editors. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), 2010; 2010: Ieee.

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van Der Mark P, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61(3):539–542.

- Ø H, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica. 2001;4(1):1–9.

- Rissler LJ, Apodaca JJ. Adding more ecology into species delimitation: ecological niche models and phylogeography help define cryptic species in the Black salamander (Aneides flavipunctatus). Syst Biol. 2007;56(6):924–942.

- Merow C, Smith MJ, Silander JA. A practical guide to MaxEnt for modeling species’ distributions: what it does, and why inputs and settings matter. Ecography. 2013;36(10):1058–1069.

- Aiello-Lammens ME, Boria RA, Radosavljevic A, et al. spThin: an R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography. 2015;38(5):541–545.

- Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, et al. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2005;25(15):1965–1978.

- Guevara L, Gerstner BE, Kass JM, et al. Toward ecologically realistic predictions of species distributions: A cross‐time example from tropical montane cloud forests. Glob Chang Biol. 2018;24(4):1511–1522.

- Warren DL, Glor RE, Turelli M. ENMTools: a toolbox for comparative studies of environmental niche models. Ecography. 2010;33(3):607–611.

- Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Modell. 2006;190(3):231–259.

- Barve N, Barve V, Jiménez-Valverde A, et al. The crucial role of the accessible area in ecological niche modeling and species distribution modeling. Ecol Modell. 2011;222(11):1810–1819.

- Elith J, Kearney M, Phillips S. The art of modelling range-shifting species. Methods Ecol Evol. 2010;1(4):330–342.

- Muscarella R, Galante PJ, Soley-Guardia M, et al. ENMeval: an R package for conducting spatially independent evaluations and estimating optimal model complexity for Maxent ecological niche models. Methods Ecol Evol. 2014;5(11):1198–1205.

- Rödder D, Engler JO. Quantitative metrics of overlaps in Grinnellian niches: advances and possible drawbacks. Global Ecol and Biogeo. 2011;20(6):915–927.

- Bangs O List of the mammals collected in the Santa Marta region of Colombia by W. W. Brown, Jr. Proceedings of the New England Zoölogical Club. 1900;1:87–102.

- Handley CO Jr. Mammals of the Smithsonian Venezuelan Project. Brigham Young Univ Sci Bulletin, Biol Ser. 1976;20(5):1–91.

- Eisenberg JF, Redford KH. Mammals of the Neotropics. The Central Tropics. Vol. 3. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press; 1999.

- Koopman KF. Zoogeography. In: Baker RJ, Jones JK Jr., Carter DC, editors. Biology of bats of the New World family Phyllostomatidae. Part I. Special Publications of the Museum 10. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press; 1976. p. 39–47.

- Koopman KF. Biogeography of the bats of South America. Mammalian biology in South America. Mares MA, Genoways HH, editors. Pittsburgh: Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology, University of Pittsburgh; 1982. The Pymatuning Symposia in Ecology 6. Special Publications Series. 273–302.

- Eisenberg JF. Mammals of the Neotropics. The northern Neotropics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1989.

- Albuja VL. Murciélagos del Ecuador. 2nd ed. Ecuador: Cicetrónica Cía. Ltda. Offset; 1999.

- Owen RD. Phylogenetic analyses of the bat subfamily Stenodermatina (Mammalia: chiroptera) Special Publication. Museum Tex Univ. 1987;26:1–65.

- Larsen PA, Siles L, Pedersen SC, et al. A new species of Micronycteris (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) from Saint Vincent, Lesser Antilles. Mammalian Biology-Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde. 2011;76(6):687–700.

- Siles L, Brooks DM, Aranibar H, et al. A new species of Micronycteris (Chiroptera: phyllostomidae) from Bolivia. J Mammal. 2013;94(4):881–896.

- Velazco PM, Cadenillas R. On the identity of Lophostoma silvicolum occidentalis (Davis & Carter, 1978)(Chiroptera: phyllostomidae). Zootaxa. 2011;2962:1–20.

- Solari S, Hoofer SR, Larsen PA, et al. Operational criteria for genetically defined species: analysis of the diversification of the small fruit-eating bats, Dermanura (Phyllosomidae: stenodermatinae). Acta Chiropterologica. 2009;11(2):279–288.

- Carrera JP, Solari S, Larsen PA, et al. Bats of the Tropical Lowlands of Western Ecuador. Spec Publication Museum Tex Univ. 2010;57:1–44.

- Velazco PM Platyrrhinus nigellus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Spe 2015. 2018:e.T136317A22020785. Downloaded on Feb 25. DOI:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T136317A22020785.en.

- Sampaio E, Lim BK, Peters S Platyrrhinus umbratus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Spe 2016. 2018:e.T95908089A21973968. Downloaded on Feb 25. DOI:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T95908089A21973968.en.

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Version 3.1. Gland (Switzerland): IUCN; 2001.

Appendices a1. Species, tissue collection number and GenBank accession numbers for the Platyrrhinus and outgroup samples used in this study.

Appendices a2. Specimens Examined

The following list includes all the specimens examined in this study, with their respective localities. Refer Materials and Methods for abbreviations. Individuals or series marked with an asterisk were used in the elaboration of and in morphometric analyses.

Platyrrhinus aquilus (3). PANAMA: Darién: Cerro Mali, Head of Río Pucro (USNM 338025 [Holotype of Vampyrops aquilus], 338026); Cerro Mali (USNM 338027).

Platyrrhinus aurarius (19). VENEZUELA: Amazonas: Cerro de la Neblina, base of Pico Maguire (FMNH 137294–137298, 137304–137307); Cerro de la Neblina, left bank of Río Baria (FMNH 137313). Bolívar: km 125, 85 km SSE El Dorado (USNM 387143–387145, 387147–387148, 387150, 387155, 387156, 387163 [Holotype of Vampyrops aurarius]).

Platyrrhinus chocoensis (20). COLOMBIA: Cauca: Alto Micay, Betania (FMNH 113745, 113821, 113824, 113828, 113829, 113,831, 113,833–113,835). Nariño: La Guayacana (USNM 309018). Valle del Cauca: Concesión Bajo Calima, Cuartel BV83 (FMNH 140696, 140697); Río Raposo (USNM 339395, 339396); Río Zabaletas, 29 km SE Buenaventura (USNM 483533, 483535, 483537–483539); Río Zabaletas, approx. 30 km SE Buenaventura (USNM 483536).

Platyrrhinus dorsalis (15). COLOMBIA: Cauca: Popayán (FMNH 90327); Charguayaco (FMNH 113538, 113539). Huila: Las Cuevas Parque, Upper Cabaña, 150 m N (FMNH 58740). Valle del Cauca: Dapa, 12 mi NW Cali (USNM 483573); Pichinde, 10 km SW Cali (USNM 483577); Pance, approx 20 km SW (USNM 483580–483585, 483593, 483598). ECUADOR: Imbabura: Paramba (BMNH 99.12.5.1 [Holotype of Vampyrops dorsalis]).

Platyrrhinus ismaeli (22). COLOMBIA: Huila: Las Cuevas Parque, upper bridge on Río Suaza (FMNH 58732, 58736); Las Cuevas Parque, Indian Cave, entrance (FMNH 58737); Las Cuevas Parque, Indian Cave, exit (FMNH 58733–58735, 58738). ECUADOR: Napo: San Rafael Cascada (FMNH 124988). Pastaza: Mera (USNM 548220–548224). PERU: Amazonas: Chachapoyas, Balsas, 19 km by rd E (FMNH 129133, 129134, 129136, 129137). Cajamarca: Celendin, Hacienda Limón (FMNH 129139, 129142, 129143, 129145, 129146).

Platyrrhinus masu (15). PERU: Cuzco: Quispicanchi, Hacienda Cadena (FMNH 93588). Quispicanchi, Collpa de San Lorenzo (FMNH 93594); Paucartambo, Consuelo, km 165, 17 km by rd W of Pilcopata (FMNH 123917 [Holotype of Platyrrhinus masu]). Madre de Dios: Manu, Alto Río Madre de Dios, Hacienda Amazonía (FMNH 139590, 139591, 139593). Cerro de Pantiacolla, above Río Palotoa (FMNH 122136, 139597–139599, 139601–139603, 139606, 139607).

Platyrrhinus umbratus [Platyrrhinus nigellus] (299). BOLIVIA: La Paz: 20 km NNE Caranavi (UMMZ 127174). COLOMBIA: Boyacá: Municipio Villa de Leyva, detrás del Instituto Humboldt, Sitio Hostería IAvH-M 6872*); Pajarito, Hacienda Camijoque (ICN 5441*); Santa Maria, Caño Negro, camino entre las fincas Santa Rosita y El Tesoro, ruta a Palo Negro (ICN 17165*,#); Santa María, Margen izquierda Río Bata, sendero ecológico (ICN 15066 *,#); Santa María, Sitio Represa Chivor, vía Batallón El Rebosadero (ICN 16352 *,#). Caquetá: Florencia, Corr. El Caraño, Vereda Las Brisas, Finca Los Lirios (UAM 190*, 192*). Cauca: Inza, Vereda Tierras Blancas, km 78 carretera Popayán-Inza (ICN 8467–8468*); PNN “Munchique” Cabaña La Romelia (IAvH-M 3314–3315*). Cesar: San Sebastián (FMNH 69484*,#); Valledupar, Villanueva, Sierra Negra (USNM 281304*). Cundinamarca: Tena, Laguna de Pedro Pablo (ICN 5293*,#, 5295*). Huila: PNN “Cueva de los Huácharos” 80 m N Cabaña La Ilusión (IAvH-M 3311*); Suaza, Vereda Alto Campo Hermoso, Finca Marllins (UAM 228*). Magdalena: Santa Marta, Santa Marta, Alto de Mira, 3 km O Río Buritaca, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (ICN 13087*). Meta: Cubarral, Vereda Aguas Claras, escuela Santa Clara, finca La Reforma (ICN 14800*,#); Restrepo, Caney Alto, bocatoma del acueducto (ICN 10147*,#); Restrepo, Salinas de Upin (ICN 14372*,#). Nariño: El Carmen (FMNH 113713, 113721, 113730–113732, 113734, 113891–113892, 113894–113897). Norte de Santander: Municipio Herrán, PNN Tamá, Sector Orocué (IAvH-M 6631–6637*, 6672*); Municipio Toledo, Río Negro, Finca San Isidro, Parque Natural Nacional Tamá (IAvH-M 6678*, 6685*, 6689*, 6701–6704*, 6710*, 6715*, 6782*); Municipio Toledo, Vereda el Diamante, Cerro San Agustín, Parque Natural Nacional Tamá (IAvH-M 6719*, 6721–6722*, 6734*, 6739*). Putumayo: Municipio Mocoa, carretera entre Sibundoy y Mocoa, Localidad El Mirador (IAvH-M 6817*, 6819*, 6825*). Quindío: Salento, Reserva Natural Cañón Quindío, frente de reforestación La Picota (ICN 12446*,#); Salento, Reserva Natural Cañón Quindío, frente de reforestación La Romelia (ICN 12441–12445*,#); Salento, Reserva Natural Cañon Quindío, frente de reforestación Monte Loro (ICN 12447–12448*,#). Risaralda: Pueblo Rico, Vereda San José, quebrada San José (ICN 11934*,#, 11937*,#). Santander: Charala, Virolín (ICN 8150*, 8972*,#, 8973*); Encino, Vereda La Cabuya, finca San Benito (ICN 17588*); Encino, Vereda Río Negro, sitio Las Tapias, finca El Aserradero (ICN 17585–17586*); Municipio Encino, Vereda Los Pericos, Finca Vegaleón (ICN 17587*); Tona, Sitio El Mortiño, carretera Bucaramanga-Cúcuta km 18 (ICN 17187–17188*,#); Tona, Vereda Guarumales, finca El Pajal (ICN 16660–16661*). Valle del Cauca: Bolívar, La Tulia, Hacienda La Argelia (UV 12112); Buga, La Magdalena, Janeiro, Hacienda Santelina (UV 13024*); El Aguila, Quebrada Charco Azul, vía a San Jorge del Palmar (UV 12522*, 12559*); El Cairo, Estacion Cerro de Inglés (UV 12242–12243*); El Cairo, Quebrada Charco Azul, vía a San Jorge del Palmar (UV 12301–12304*, 12306–12307*); Florida, Hacienda Los Alpes (UV 3525–3526*). ECUADOR: Azuay: Yunguilla Valley (FMNH 53,504). El Oro: 1 km SW Puente de Moro Moro (USNM 513465*,#); Zaruma, 3 km N, Minas Miranda (USNM 534249*,#). Napo: San Rafael Cascada (FMNH 124987*,#). Pastaza: Mera (USNM 548189–548195*,#; 548196–548210*; 548399*). PERU: Amazonas: Cordillera Del Cóndor, Valle Río Comaina, Puesto Vigilancia 3, Alfonso Ugarte (USNM 581960*,#). Ayacucho: La Mar, Ayna, Centabamba (MUSM 21405). Cajamarca: Jaén, Chontalí, Las Ashitas, 4 km oeste de Pachapiriana (MUSM 10652); San Ignacio, El Sauce (MUSM 18174, 18226–18229); San Ignacio, Chirinos, Nuevo Chalaquito. “El Chaupe” (MUSM 12890–12892); San Ignacio, Tabaconas, 4 km oeste de El Chaupe (MUSM 10651). Cuzco: La Convención, Ridge Camp (USNM 588031*,#, 588085); La Convención, Camisea, Cashiriari (MUSM 13863–13864); La Convención, Kimbiri, Camp. Wayrapata (MUSM 14579); La Convención, a 2 km SO de C.N. Tangoshiari (MUSM 13394); La Convención, Pichari, Catarata (MUSM 21406); La Convención, Kimbiri, Camp. Llactahuaman (MUSM 14573–14578); Paucartambo, Challabamba, Bosque de las Nubes, carretera Paucartambo-Pillcopata, km 150, puente (MUSM 8857); Paucartambo, Kosñipata, Consuelo, km 165, 17 km by rd W of Pilcopata (FMNH 123934–123946, 123947*,#, FMNH 123948–123949, MUSM 9970–9975); Paucartambo, Kosñipata, Consuelo, 15.9 km SW Pilcopata (FMNH 174773–174783, MUSM 19734–19738); Paucartambo, Kosñipata, Quitacalzon, carretera Paucartambo-Pillcopata, puente a 163 km (MUSM 8858–8860); Paucartambo, Kosñipata, P. N. Manu, San Pedro (MUSM 8861, 11796, 15409, 19449; FMNH 172104–172106); Paucartambo, Tono, ca. 5 km S of Río Tono and 18 road km W of Patria (FMNH 139589, 139759; MUSM 9977); Quispicanchi, Collpa de San Lorenzo (FMNH 93589, 93590–93593*,#, 93595–93597*,#, 93607*,#); Quispicanchi, Hacienda Cadena (FMNH 93598–93601*,#, 93602, 93603–93606*,#). Huánuco: Caserío San Pedro de Carpish, Distrito de Chinchao, Cordillera de Carpish (MUSM 18273). Junín: Satipo, Río Tambo, Cordillera del Vilcabamba (MUSM 12995). Madre de Dios: Manu, Alto Río Madre de Dios, Hacienda Amazonia (FMNH 126031–126032*,#, 139573, 139761–139763, 139765–139775, 139778–139784; MUSM 9955–9962); Manu, Cerro de Pantiacolla, above Río Palotoa (FMNH 139576–139578*,#, 139579, 139580*,#, 139786–139803; MUSM 9963–9969); Manu, Río Palotoa, left bank, 12 km upstream from mouth (FMNH 139804; MUSM 9976). Pasco: Oxapampa, Pozuzo, Palmira (MUSM 10943–10944, 10971–10972). San Martín: Huallaga, entre “La Morada” y “La Rivera” (MUSM 16170–16179); Mariscal Cáceres, P.N. Río Abiseo, Las Palmas (MUSM 7295–7296).

Platyrrhinus umbratus [Platyrrhinus umbratus] (280). COLOMBIA: Boyacá: Pajarito, Corinto, Finca El Descanso, quebrada Conguta (ICN 8351*); Pajarito, Hacienda Camijoque (ICN 8039*, 17111*,#). Cesar: Valledupar, Villanueva, Sierra Negra (USNM 281303*, 281305*, 281924*, 281925). Chocó: Bahía Solano (Mutis), 5 km por la Carretera al SW (UV 4149–4150*, 4152*). Cundinamarca: Tena, Laguna de Pedro Pablo (ICN 5292*, 5294*,#, 5537*,#, 5538*, 5540*). Huila/Cauca: Moscopas, Río La Plata (USNM 483574*,#, 483576*,#). La Guajira: San Antonio (MCZ B8300); San Miguel, 60 km NNW Valledupar (MCZ B8180*,#). Magdalena: Palomino (MCZ B8301); Santa Marta, Serranía San Lorenzo, Estación Inderena (ICN 5388–5391*,#). Meta: Restrepo (USNM 596973–596975, 596977–597013; UV 3850*). Risaralda: Santa Rosa de Cabal, Laguna del Otún (El Porvenir) (UV 2517–2518*, 2520*). Santander: Charala, Virolín (ICN 6695–6697*,#). Valle del Cauca: 2 km S Pance, approx. 20 km SW Cali (USNM 483586–483592*,#, 483594–483596*,#, 483597*, 483599–483601*,#; UV 769*, 1234*); Corea, Los Farallones (UV 7574*); Dagua, El Queramal, Tokio. Antena Tele (UV 2027*); Florida, Hacienda Los Alpes (UV 7575*, 10836). VENEZUELA: Aragua: Estación Biológica Rancho Grande, Parque Nacional Henri Pittier, 14 km NW Maracay (USNM 370514–370516*, 517465*, 562897–562899, 562906); Maracay, 13 km NW, Pico Guayamayo, Above Rancho Grande (USNM 521560–521562); Paso El Portachelo, Parque Nacional Henri Pittier, 14 km NW Maracay (USNM 517466*, 562900–562905, 562907–562914). Carabobo: Cerro La Copa, 4 km NW Montalbán (USNM 440651–440656*, 443363, 496546–496547); Palmichal, 23 km N. Bejuma (USNM 562915). Distrito Capital: 0.5 km W junction Colonia Tovar and Puerto Cruz highways (USNM 562985*, 562986–562987); Boca Tigre Valley, 5 km NW Caracas, nr. Clavelitos (USNM 370470*, 370472*, 370473*, 370477–370478*, 496762–496766); Hotel Humboldt, Cerro Ávila, 12 km N Caracas (USNM 370452–370456*, 370462*, 370480–370490*, 370509–370511*, 372128*, 496538, 496775); Los Venados, 4 km NNW Caracas (USNM 370409–370410*,#, 370412*,#, 370414–370416*,#, 370418*, 370429*, 370431–370447*, 408289, 496753–496761, 370407–370408*,#, 370411*,#, 370413*,#). Mérida: Fundo Monteverde, 6.5 km La Azulita (CVULA 8774–8775*,#); La Carbonera, 12 km SE La Azulita (USNM 387116–387118*); La Mucuy, 4 km E Tabay (USNM 373837–373839*, 496540); La Pedregosa Norte, 3 km N Puente de La Pedregosa (UV 11832*); Sector Cucuchica, 5.8 km ENE Tovar (CVULA 8776–8778*,#); Tabay, 6 km ESE Tabay, Middle Refugio (USNM 387110–387115*). Miranda: Hotel Humboldt, Cerro Ávila, 12 km N Caracas (USNM 496539, 496772–496774); near Curupao, 5 km NNW Guarenas (USNM 387126–387141*, 496776–496783). Monagas: Caripe (USNM 522936, 534251); San Agustín, Distrito Caripe (USNM 408566–408568*). Trujillo: Hacienda Misisí, 13 km E Trujillo (USNM 373834–373836*). Vargas: Alto de Ño Leon, 28 km WSW Caracas (USNM 408559–408564*); Cerro Ávila, estación de bombeo, 12 km N Caracas (UV 11467–11468*); Galipán, Cerro Ávila, 5.7 km NE Caracas (BMNH 14.7.27.1*,#); Near Boca de Tigre, Cerro Ávila, 12 km N Caracas (USNM 370491–370494*, 370500–370508*). Yaracuy: Minas de Aroa, 20 km NW San Felipe (USNM 440647*).

Appendices a3. Platyrrhinus umbratus localities

The following list includes all localities with their respective coordinates used in the Ecological Niche Modeling analyses.

Platyrrhinus umbratus [Platyrrhinus nigellus]. BOLIVIA: La Paz: 20 km NNE Caranavi (−15.66667, −67.50000). COLOMBIA: Boyacá: Municipio Villa de Leyva, detrás del Instituto Humboldt, Sitio Hosteria (5.63440, −73.52000); Pajarito, Hacienda Camijoque (5.30000, −72.70000); Santa María, Sitio Represa Chivor, vía Batallón El Rebosadero (4.95580, −73.10510). Cauca: Inza, Vereda Tierras Blancas, km 78 carretera Popayán-Inza (2.55160, −76.06510). Cesar: San Sebastián (10.56667, −73.60000). Cundinamarca: Tena, Laguna de Pedro Pablo (4.68333, −74.38333). Huila: PNN “Cueva de los Huacharos” 80 m N Cabaña La Ilusión (1.63333, −75.96667); Suaza, Vereda Alto Campo Hermoso, Finca Marllins (1.96650, −75.80800). Magdalena: Santa Marta, Alto de Mira, 3 Km. O Río Buritaca, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (11.11156, −74.05481). Meta: Cubarral, Vereda Aguas Claras, escuela Santa Clara, finca La Reforma (3.53700, −74.06000); Restrepo, Caney Alto, bocatoma del acueducto (4.28333, −73.58333); Restrepo, Salinas de Upín (4.25000, −73.58667). Nariño: El Carmen (0.66667, −77.16667). Norte de Santander: Municipio Herrán, PNN Tamá, Sector Orocué (7.42528, −72.44389); Municipio Toledo, Río Negro, Finca San Isidro, Parque Natural Nacional Tamá (7.11667, −72.25000); Municipio Toledo, Vereda el Diamante, Cerro San Agustín, Parque Natural Nacional Tamá (7.10167, −72.22167). Putumayo: Municipio Mocoa, carretera entre Sibundoy y Mocoa, Localidad El Mirador (1.06972, −76.74472). Quindío: Salento, Reserva Natural Cañón Quindío, frente de reforestación Monte Loro (4.63730, −75.57000). Risaralda: Pueblo Rico, Vereda San José, quebrada San José (5.22220, −76.03105). Santander: Charala, Virolín (6.10528, −73.22222); Encino, Vereda La Cabuya, finca San Benito (6.15000, −73.06667); Encino, Vereda Río Negro, sitio Las Tapias, finca El Aserradero (6.10000, −73.10000); Municipio Encino, Vereda Los Pericos, Finca Vegaleón (6.16667, −73.13333); Tona, Vereda Guarumales, finca El Pajal (7.20180, −72.96670). Valle del Cauca: Bolívar, La Tulia, Hacienda La Argelia (4.38510, −76.24420); Buga, La Magdalena, Janeiro, Hacienda Santelina (3.83889, −76.19528); El Águila, Quebrada Charco Azul, vía a San Jorge del Palmar (4.90910, −76.04299); El Cairo, Estación Cerro de Inglés (4.76100, −76.22210); Florida, Hacienda Los Alpes (3.26667, −76.15000). ECUADOR: Azuay: Yunguilla Valley (−3.43300, −79.18300). El Oro: 1 km SW Puente de Moro Moro (−3.73333, −79.73333); Zaruma, 3 km N, Minas Miranda (−3.68333, −79.61667). Napo: San Rafael Cascada (−0.96667, −77.78333). Pastaza: Mera (1.46667, −78.10000). PERU: Amazonas: Cordillera del Cóndor, Valle Río Comaina, Puesto Vigilancia 3, Alfonso Ugarte (−3.90806, −78.42111). Ayacucho: La Mar, Ayna, Centabamba (−12.69445, −73.56334). Cajamarca: Jaén, Chontali, Las Ashitas, 4 km. oeste de Pachapiriana (−5.65521, −79.16010); San Ignacio, El Sauce (−5.17842, −79.16292); San Ignacio, Chirinos, Nuevo Chalaquito, “El Chaupe” (−5.20444, −79.02522); San Ignacio, Tabaconas, 4 km. oeste de El Chaupe (−5.20541, −79.06060). Cuzco: La Convención, Ridge Camp (−11.77944, −73.34056); La Convención, Camisea, Cashiriari (−11.82430, −72.82007); La Convención, Kimbiri, Campamento Wayrapata (−12.83600, −73.49500); La Convención, a 2 km SO de C.N. Tangoshiari (−11.77972, −73.34069); La Convención, Pichari, Catarata (−12.53639, −73.77028); La Convención, Kimbiri, Campamento Llactahuaman (−12.86500, −73.51300); Paucartambo, Challabamba, Bosque de las Nubes, carretera Paucartambo-Pillcopata, km 150, puente (−13.079525, −71.560045); Paucartambo, Consuelo, km 165, 17 km by rd W of Pilcopata (−13.13000, −71.25000); Paucartambo, Kosñipata, P. N. Manu, San Pedro (−13.05467, −71.54623); Paucartambo, Kosñipata, Quitacalzón, carretera Paucartambo-Pillcopata, puente a 163 km (−12.99390, −71.45400); Paucartambo, Tono, ca. 5 km S of Río Tono and 18 road km W of Patria (−13.13330, −71.33330); Quispicanchi, Collpa de San Lorenzo (−13.40000, −70.76667); Quispicanchi, Hacienda Cadena (−13.40000, −70.71667). Huánuco: Distrito de Chinchao, Cordillera de Carpish, Caserío San Pedro de Carpish (−9.700816, −76.078994). Junín: Satipo, Río Tambo, Cordillera del Vilcabamba (−11.55972, −73.64111). Madre de Dios: Manu, Alto Río Madre de Dios, Hacienda Amazonia (−12.93330, −71.25000); Manu, Cerro de Pantiacolla, above Río Palotoa (−12.60000, −71.32000); Manu, Río Palotoa, left bank, 12 km upstream from mouth (−12.57670, −71.43560). Pasco: Oxapampa, Pozuzo, Palmira (−10.06285, −75.53682). San Martín: Mariscal Cáceres, P.N. Río Abiseo, Las Palmas (−7.68193, −77.21901).

Platyrrhinus umbratus [Platyrrhinus umbratus]. COLOMBIA: Boyacá: Pajarito, Hacienda Camijoque (5.30000, −72.70000). Chocó: Bahía Solano (Mutis), 5 km por la Carretera al SW (4.08333, −75.20000). Cundinamarca: Tena, Laguna de Pedro Pablo (4.68333, −74.38333). Huila/Cauca: Moscopas, Río La Plata (2.26667, −76.16667). La Guajira: San Antonio (11.05000, −73.43333); San Miguel, 60 km NNW Valledupar (10.96166, −73.48018). Magdalena: Palomino (11.03333, −73.65000); Santa Marta, Serranía San Lorenzo, Estación Inderena (11.11667, −74.05000). Meta: Restrepo (4.25000, −73.58667). Santander: Charala, Virolín (6.10528, −73.22222). Valle del Cauca: 2 km S Pance, approx. 20 km SW Cali (3.31667, −76.63333); Cali, Corea, Los Farallones (3.30770, −76.71050); Dagua, El Queramal, Tokio, Antena Tele (3.66667, −76.70000); Florida, Hacienda Los Alpes (3.26667, −76.15000). VENEZUELA: Aragua: Estación Biológica Rancho Grande, Parque Nacional Henri Pittier, 14 km NW Maracay (10.34917, −67.68417); Maracay, 13 Km NW, Pico Guayamayo, above Rancho Grande (10.35000, −67.66667); Paso El Portachelo, Parque Nacional Henri Pittier, 14 km NW Maracay (10.35000, −67.68333). Carabobo: Cerro La Copa, 4 km NW Montalbán (10.25000, −68.36667); Palmichal, 23 Km N. Bejuma (10.19910, −68.25860). Distrito Capital: 0.5 km W junction Colonia Tovar and Puerto Cruz highways (10.42976, −67.18282); Boca Tigre Valley, 5 Km NW Caracas, nr. Clavelitos (10.53333, −66.90000); Hotel Humboldt, Cerro Ávila, 12 km N Caracas (10.54194, −66.87583). Mérida: Fundo Monteverde, 6.5 km La Azulita (8.76000, −71.48000); La Carbonera, 12 Km SE La Azulita (8.63333, −71.35000); La Mucuy, 4 km E Tabay (8.63333, −71.03333); La Pedregosa Norte, 3 km N Puente de La Pedregosa (8.60000, −71.18333); Sector Cucuchica, 5.8 km ENE Tovar (8.34000, −71.70000); Tabay, 6 Km ESE Tabay, middle Refugio (8.61667, −71.03333). Miranda: near Curupao, 5 Km NNW Guarenas (10.51667, −66.63333). Monagas: Caripe (10.17560, −63.50680); San Agustín, Distrito Caripe (10.20000, −63.55000). Trujillo: Hacienda Misisí, 13 Km E Trujillo (9.35000, −70.30000). Vargas: Alto de Ño Leon, 28 Km WSW Caracas (10.43575, −67.16124); Cerro Ávila, estación de bombeo, 12 km N Caracas (10.54137, −66.87914); Galipán, Cerro Ávila, 5.7 km NE Caracas (10.55299, −66.89409); Near Boca de Tigre, Cerro Ávila, 12 km N Caracas (10.55000, −66.90000). Yaracuy: Minas De Aroa, 20 Km NW San Felipe (10.41667, −68.90000).