ABSTRACT

With the third most biodiverse amphibian fauna in the world, Ecuador has bolstered this claim with a particularly high rate of species descriptions in recent years. Many of the species being described are already facing anthropogenic threats despite being discovered within privately protected reserves in areas previously not sampled. Herein we describe a new species of terrestrial frog in the genus Noblella from the recently established Río Manduriacu Reserve, Imbabura, Ecuador. Noblella worleyae sp. nov. differs from its congeners by having a dorsum finely shagreen; tips of Fingers I and IV slightly acuminate, Fingers II and III acuminate, without papillae; distal phalanges of the hand slightly T-shaped; absence of distinctive suprainguinal marks; venter yellowish-cream with minute speckling and throat with irregular brown marks to homogeneously brown. We provide a detailed description of the advertisement call of the new species and present an updated phylogeny of the genus Noblella. In addition, we emphasize the importance of the Río Manduriacu Reserve as a conservation area to threatened fauna.

Ecuador es el tercer país más diverso en anfibios, y la descripción de especies en los últimos años ha aumentado considerablemente, evidenciando la presencia de nuevas especies en áreas privadas protegidas, muchas de las cuales enfrentan amenazas antropogénicas. Aquí describimos una nueva especie de rana terrestre del género Noblella de la vertiente pacífica de los Andes ecuatorianos en la Reserva Río Manduriacu, provincia de Imbabura. Noblella worleyae sp. nov. se diferencia de sus congéneres por la presencia de un dorso finamente granular, puntas de los dedos I y IV ligeramente acuminados, dedos II y III acuminados, sin papila; falanges distales de la mano ligeramente en forma de T; ausencia de marcas distintivas suprainguinales; vientre crema amarillento moteado con diminutos puntos ,garganta con marcas cafés irregulares a homogéneamente café. Proporcionamos una descripción detallada del canto de la nueva especie y presentamos una filogenia actualizada del género Noblella. Además, enfatizamos la importancia de la Reserva Río Manduriacu como un área de conservación para fauna amenazada.

Introduction

The genus Noblella Barbour [Citation1] currently contains 15 described species. Approximately half of these ground-dwelling, terrestrial-breeding frogs have been described in the last decade alone [Citation2]. The genus is distributed from Colombia to Bolivia on both versants of the Andes, with the exception of N. myrmecoides, which occurs in the lowlands of the Amazon basin from southeastern Colombia to Bolivia, and Noblella losamigos, which occurs along the eastern slopes of the Andes and adjacent Amazonian lowlands in southeastern Peru [Citation2]. Members of Noblella are some of the smallest frogs (SVL < 25 mm), with N. pygmaea being the smallest known species in the Andes [Citation3,Citation4]. Some of the external morphological characteristics that distinguish the genus are small size, head narrower than body, terminal discs of fingers and toes not expanded, conspicuous tarsal tubercle, and phalangeal reduction in Finger IV (in several species). Nevertheless there are no known morphological synapomorphies for the genus. See Hedges et al. [Citation5] for additional characters.

Although Noblella is a morphologically homogenous taxon, it is not monophyletic in molecular phylogenies [Citation4,Citation6,Citation7]. The absence of genetic information for the type species of Noblella and the morphologically similar Psychrophrynella adds ambiguity when allocating newly described species into a genus [Citation4,Citation6,Citation7].

Although not rare in collections (e.g. Ecuadorian museums have good representation of the genus, mainly from the eastern slopes), the taxonomy of the genus is complex because of the morphological similarity among populations [Citation8]. The majority of Noblella spp. have been described from the Amazonian versant of the Andes, with just two species known from the Pacific slopes of the Andes, namely N. coloma (northwest) and N. heyeri (southwest) [Citation9,Citation10]. Herein, we describe a new species of Noblella from the Río Manduriacu Reserve situated on the Pacific slope of the Ecuadorian Andes, a region facing rapidly advancing mining activities and, thus, a precarious future. The new species is morphologically and phylogenetically similar to N. coloma; however, it is easily distinguished from the latter by having distal phalanges of the hand slightly T-shaped (distinctly T-shaped in N. coloma), absence of distinctive suprainguinal marks (present in N. coloma), venter yellowish-cream with minute speckling (orange with minute brown and white spots in N. coloma), and throat with irregular brown marks to homogeneously brown (orange with minute white spots in N. coloma).

Materials and methods

Taxonomy and species concept

We follow the generic and family names proposed by De la Riva et al. [Citation8] and Heinicke et al. [Citation11], respectively. We adopted the unified species concept [Citation12,Citation13] for recognizing species, which considers that independent evolutionary lineages exhibit consistent diagnostic traits (i.e., morphological, behavioral, genetic). Specimens examined are listed in Appendix I and institutional acronyms are those of Frost [Citation2].

Field work

We carried out exhaustive samplings in the Río Manduriacu Reserve in search of amphibians and reptiles of importance for conservation, with the purpose of promoting conservation efforts in the network of reserves managed by the EcoMinga Foundation, especially in light of the mining threat at this particular reserve [Citation4,Citation14–16]. Samples were collected within the Río Manduriacu Reserve between 2012 and 2019 during the following periods: November 7–8, 2012; May 13–15, 2013; February 21–22, 2014; October 17–30, 2016; April 9–12, 2017; January 20–30, 2018; February 5–13, 2018; February 28 to 12 March 2019 (see Guayasamin et al. [Citation14]; note the corrected year for sampling in April from 2018 to 2017). The most recent fieldwork in Feb–March, 2019, was conducted by SK, RJM, SJT, JC, José Maria Loaiza, and three assistants. The primary sampling methods were visual encounter surveys and general area searches. Visual encounter surveys were conducted from 1900 h and 0200 h along forest trails, streams, and a dirt road extending from the community to the Río Manduriacu Reserve, and encompassed primary, secondary, and riparian forest, as well as forest clearings. General area searches were performed by day and night, and were often utilized when habitat complexity did not permit linear transects. Data collection included the following information: species ID, date, time, habitat type, microhabitat, perch height/diameter (when applicable), behaviour, and geographic coordinates. A Garmin GPSmap 62s was used to demarcate transects and record coordinates for specimens.

Evolutionary relationships

We generated mitochondrial sequences (16S) for individuals of the new species of Noblella (ZSFQ 550, 551, 2502), as well as for N. coloma (QCAZ 32702, 40579). Extraction, amplification, and sequencing protocols are as described in Guayasamin et al. [Citation17]. The obtained sequences were compared with closely related taxa (see [Citation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation18]) downloaded from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). We generated five new sequences (three for the new species and two for Noblella coloma), which were compared with 44 sequences (43 species) downloaded from Genbank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). All Genbank codes are in . Sequences were aligned using MAFFT v.7 (Multiple Alignment Program for Amino Acid or Nucleotide Sequences: http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/) [Citation19], with the Q-INS-i strategy. MacClade 4.07 [Citation20] was used to visualize the alignment and minimize gap openings; characters where the alignment was ambiguous were excluded. Maximum likelihood (ML) trees were estimated using GARLI 2.01 (Genetic Algorithm for Rapid Likelihood Inference [Citation21]), which uses a genetic algorithm that finds the tree topology, branch lengths, and model parameters that maximize lnL simultaneously [Citation21]. Individual solutions were selected after 10,000 generations with no significant improvement in likelihood, with the significant topological improvement level set at 0.01; the final solution was selected when the total improvement in likelihood score was lower than 0.05, compared to the last solution obtained. Default values were used for all other GARLI settings, as recommended by the developer [Citation21]. Bootstrap support was assessed via 1,000 pseudoreplicates under the same settings used in tree search. GenBank accession numbers are included in Table S1.

Morphological data

Before the preservation of specimens, tissue of liver and leg muscle was extracted and deposited in Eppendorf tubes with 95% ethanol. Individuals were euthanized with benzocaine atomizer and then fixed with either 10% formaldehyde or 95% ethanol; all individuals were preserved in 75% ethanol. The specimens were deposited at the Museo de Zoología COCIBA-USFQ (ZSFQ) of the Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Ecuador. Several species of Noblella were examined (see Appendix I, ).

We measured all collected specimens with a digital caliper (Mitutoyo ABSOLUTE 500–195-20) to the nearest 0.01 mm, following the descriptions provided by Guayasamin and Terán-Valdez [Citation9]: snout to vent length; tibia length; foot length; head length; head width; interorbital distance; upper eyelid width; internarial distance; eye-nostril distance; snout-eye distance; diameter of the eye; diameter of tympanum; eye-tympanum distance; forearm length; and hand length. Sexual maturity was assessed by the presence of vocal sac and/or vocal slits for adult males and the presence of convoluted oviducts for adult females.

We cleared and stained the hands and feet of specimens with Alcian Blue following the protocols proposed by Taylor and Van Dyke [Citation22]. Illustrations were made with the help of an Olympus S2X16 stereo dissecting microscope with an Olympus DP73 camera included. We follow the osteological terminology for hands and feet proposed by Duellman and Trueb [Citation23], Fabrezi [Citation24,Citation25], and Trueb [Citation26,Citation27].

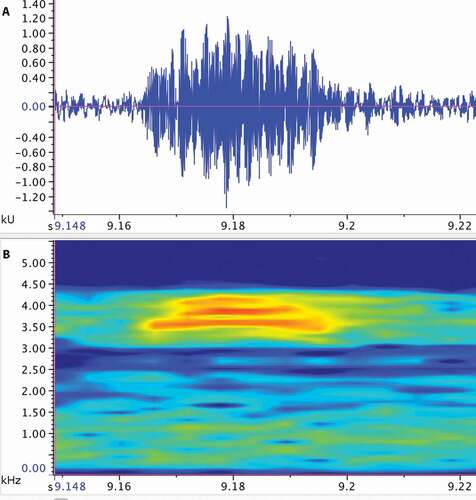

Bioacoustics

Advertisement call recordings were made by José Vieira and Jorge Brito with an Olympus LS-10 Linear PCM Field Recorder and a Sennheiser K6–ME 66 unidirectional microphone. The calls were recorded in WAV format with a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz/second with 16 bits/sample and analyzed with Raven Pro version 1.5 [Citation28]. All calls are stored at the Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva at Universidad San Francisco de Quito (LBE-USFQ). Measurements of acoustic variables were obtained as described in Köhler et al. [Citation29]. A call is defined as the collection of acoustic signals emitted in sequence and produced in a single exhalation of air. A note is defined as a temporally distinct segment within a call; notes are separated by a silent interval. Pulsed notes are defined as: notes having one or more clear amplitude peaks but are not separated by a fully silent interval. Tonal notes are defined as: notes that maintain relatively constant amplitude throughout the call. A call series (or call group) is defined as a sequence of calls that is separated from other such groups by periods of silence much longer than the inter-call intervals, which are stable or changing in a predictable pattern (see [Citation29]).

Results

Phylogenetic relationships and genetic distances

The resulting mitochondrial tree of Noblella and outgroups is shown in . Noblella, as currently defined, is not monophyletic. The new species is inferred as sister to N. coloma. The two species have a considerable genetic distance between them (uncorrected p = 0.066).

Systematics accounts

Noblella worleyae new species

Figure 2. Map of Ecuador showing the location of Río Manduriacu Reserve, the type locality (red triangle) of Noblella worleyae sp. nov

Figure 3. Noblella worleyae sp. nov., holotype, ZSFQ 551, adult female, SVL = 18.1 mm. (A) palmar surface; (B) plantar surface; (C) dorsal view of the head; (D) lateral view of the head. Illustrations by Carolina Reyes-Puig

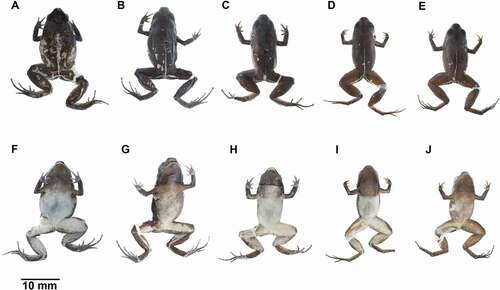

Figure 4. Color variation of preserved Noblella worleyae sp. nov. (A, F) ZSFQ 551, holotype, adult female, SVL = 18.1 mm; (B , G) ZSFQ 552, paratype, adult female, SVL = 19.1 mm; (C, H) ZSFQ 550, paratype, adult male, SVL = 17.3 mm; (D, I) ZSFQ 2502, paratype, adult male, SVL = 15.9 mm; (e, j) ZSFQ 2504, paratype, adult male, SVL = 15.5 mm

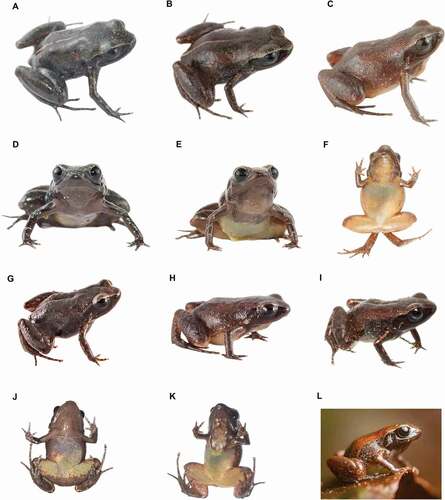

Figure 5. Dorsal and ventral color patterns of Noblella worleyae sp. nov. in life. (A, D) Dorsal pattern and ventral pattern of ZSFQ 2504, paratype, adult male, SVL = 15.5 mm; (B, E) dorsal pattern and ventral pattern of ZSFQ 2502, paratype, adult male, SVL = 15.9 mm; (C, F) dorsal pattern and ventral pattern of ZSFQ 550, paratype, adult male, SVL = 17.3 mm; (G, J) dorsal pattern and ventral pattern of ZSFQ 552, paratype, adult female, SVL = 19.1 mm; (H, K–L) dorsal pattern and ventral pattern of ZSFQ 550, paratype, adult male, SVL = 17.3 mm; (I) dorsal pattern of an uncollected specimen. Photographs by Jaime Culebras (a, b, d, e), José Vieira (c, f), Ross Maynard (g–k) and Scott Trageser (l)

Figure 6. Right hand (A) and foot (B) in dorsal view of Noblella worleyae sp. nov. ZSFQ 345, paratype, adult male, SVL = 17.9 mm

Publication LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:04BB1FF5-A8BD-43E4-BE10- F2BE767ACFE3

Taxonomic act LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:A9FF401F-BF55-4837-AAB2-4BA38B00000A

Proposed standard English name. Worley´s Leaf FrogProposed standard Spanish name. Cutín Noble de Worley

Holotype

ZSFQ 551 (), adult female, collected at Río Manduriacu Reserve (0.312057°N, 78.854330°W; 1184 m, ), Cantón Cotacachi, Imbabura Province, by Ross Maynard, Paul S. Hamilton, Scott J. Trageser and José Vieira on 8 February 2018.

Paratypes (4 males, 2 females). ZSFQ 552, adult female, collected at Río Manduriacu Reserve (0.314256°N, 78.865672°W; 1597 m), Cantón Cotacachi, Imbabura province, Ecuador, by Ross Maynard and Paul S. Hamilton on January 29th, 2018; ZSFQ 550, adult male, collected at Río Manduriacu Reserve (0.317069°N, 78.870297°W; 1701 m), Cantón Cotacachi, Imbabura province, Ecuador, by Ross Maynard, Paul S. Hamilton, and José Vieira on 11 February 2018; ZSFQ 345, adult male, collected in the Río Manduriacu Reserve, Cantón Cotacachi, Imbabura province, Ecuador (0.310502°N, 78.856872°W; 1203 m), by Ross Maynard and Paul S. Hamilton on October 19th, 2016; ZSFQ 2502, 2504 adult males, collected at Río Manduriacu Reserve (0.309800°N, 78.857298°W; 1206 m), Cantón Cotacachi, Imbabura province, Ecuador, by Jorge Brito M., Jaime Culebras, and Sebastián Kohn on 9 April 2017; ZSFQ 2503 adult female, collected at Río Manduriacu Reserve (0.310643°N, 78.856117°W; 1222 m), Cantón Cotacachi, Imbabura province, Ecuador, by Jorge Brito M., Jaime Culebras, and Sebastián Kohn on 10 April 2017.

Generic placement

The new species is placed in the genus Noblella based on morphological and molecular features. The taxon is recovered as a close relative of other Noblella species () and also matches the diagnosis of Noblella by Hedges [Citation5], as follows: head no wider than body; cranial crests absent; tympanic membrane differentiated (except in N. duellmani); dentigerous processes of vomers absent; terminal discs on digits not or slightly expanded; discs and circumferential grooves present (except in N. naturetrekii and N. worleyae sp. nov.); distal phalanges narrowly T-shaped; Finger I shorter than, or equal in length to, Finger II; most species with phalangeal reduction in Finger IV (two phalanges in N. carrascoicola, N. lochites, N. myrmecoides, N. personina, N. peruviana, N. madreselva, N. naturetrek, and N. ritarasquinae); Toe III shorter than Toe V (except in N. naturetrekii and N. worleyae sp. nov.); tips of at least Toes III–IV acuminate; subarticular tubercles not protruding; dorsum pustulate or shagreen; venter smooth; SVL less than 22 mm.

Diagnosis

The new species () presents the following characteristics: (1) skin of dorsum finely shagreen; (2) tympanic annulus and membrane visible externally, supratympanic slightly visible; (3) snout rounded in dorsal and lateral view (eye-nostril distance 55% of eye diameter, ); (4) dentigerous processes of vomers absent; (5) fingers not expanded distally, tips of Fingers I and IV slightly acuminate, Fingers II and III acuminate, without papillae (); Finger I shorter than Finger II (); nuptial pads not visible; circumferential grooves absent; (6) distal phalanges slightly T-shaped; phalangeal formula of hands: 2, 2, 3, 3 (); (7) supernumerary palmar tubercles present, mostly at the base of the digits; subarticular tubercles rounded, proximal tubercles prominent; diminutive rounded ulnar tubercles present; (8) one elongated and subconical tarsal tubercle, two tarsal tubercles (inner tubercle 2–2.5x the size of the outer), small pigmented supernumerary tarsal tubercles, toes slightly expanded and slightly acuminate on Toes I and V, and cuspidate tips on Toes II–IV, papillae absent (); (9) Toe V shorter than Toe III, distal portions of circumferential grooves present on Toes II–V, phalangeal formula of feet: 2, 2, 3, 4, 3 (); (11) in life, dorsum brown to dark brown and densely splashed with light brown, brownish-gray, or turquoise, presence of a middorsal line continuing along the posterior lengths of hind legs cream to light brown; flanks light brown to dark brown with scattered irregular white to turquoise marks; venter yellowish-cream with minute speckling; throat with irregular brown to homogeneously brown marks (); (12) female SVL 18.1–19.1 mm (n = 3, mean = 18.7); male SVL 15.5–17.9 mm (n = 4, mean = 16.6).

Comparisons

Noblella worleyae is closely related and morphologically similar to N. coloma. Nevertheless, distal phalanges of the feet and hands of the new species are only slightly expanded laterally, as opposed to a distinct T-shape in N. Coloma [Citation9], ). Moreover, the new species has a yellowish-cream venter with minute speckling (venter orange with minute brown and white spots in N. coloma), throat with irregular brown marks to homogeneously brown, and lacks suprainguinal marks (present in N. coloma).

Other species of Noblella that have three phalanges on Finger IV are N. duellmani [Citation30], N. heyeri [Citation10], N. lynchi [Citation31], N. pygmaea [Citation32], and N. thiuni [Citation33]. All of them, except N. heyeri, are restricted to the Amazonian slopes of the Andes. Moreover, N. worleyae has a tympanic annulus and membrane visible externally (absent in N. duellmani, tympanic membrane not differentiated in N. thiuni), dorsum finely shagreen (smooth in N. heyeri, pustular in N. lynchi, and tubercular in N. pygmaea).

Noblella worleyae can be distinguished from N. carrascoicola [Citation34], N. lochites [Citation35], N. losamigos [Citation36], N. myrmecoides [Citation35], N. personina [Citation37], N. peruviana [Citation38], N. madreselva [Citation39], N. naturetrekii [Citation4], and N. ritarasquinae [Citation40] by having three phalanges on Finger IV instead of two. Additionally, as mentioned before, N. worleyae, N. coloma, and N. heyeri are the only species in the genus found on the Pacific slope of the Andes.

Description of the Holotype

Adult female (ZSFQ 551); head longer than wide; snout round in dorsal and lateral views; canthus rostralis straight; loreal region slightly concave; upper eyelid 47% of interorbital distance; eye-nostril distance 66% of eye diameter; tympanum visible externally, tympanic membrane differentiated from surrounding skin; supratympanic fold slightly visible. Dentigerous processes of vomers absent. Skin of dorsum finely shagreen; venter smooth; few diminutives rounded ulnar tubercles; palmar tubercle oval, about 0.5x the size of thenar tubercle; supernumerary palmar tubercles present, mainly at base of digits; proximal subarticular tubercles prominent, rounded; fingers not expanded distally, tips of Fingers I and IV slightly acuminate, Fingers II and III acuminate, without papillae, circumferential grooves absent; relative lengths of fingers I < II < IV < III.

One elongated and subconical tarsal tubercle, two tarsal tubercles (inner tubercle 2 x the size of external); proximal subarticular tubercles well defined; small pigmented supernumerary tubercles. Toes slightly expanded and slightly acuminate on Toes I and V, cuspidate tips on Toes II–IV, distal portions of circumferential grooves visible; relative lengths of toes I < II < V < III < IV. For measurements of type series (mm) see .

Table 1. Measurements (in mm) of type series of Noblella worleyae sp. nov. Ranges followed by mean and standard deviation in parentheses

Color of holotype in life

Dorsum brown, densely splashed with light brown; cream middorsal line continued along posterior lengths of hind legs; flanks light brown with scattered irregular white marks; venter yellowish-cream with minute speckling; throat with big irregular brown marks. Iris reddish-brown with some dark brown reticulations.

Color of holotype in ethanol ()

Dorsum brown (flecked with white by preservation effects and manipulation); cream middorsal stripe, extending from scapular level to cloaca and then along the posterior surface of hind limb. Sides of head homogeneously dark brown, labial bars absent, with a faded post-tympanic fringe; flanks flecked with cream. Venter and ventral surfaces of legs white with scattered diminutive brown dots; throat brown with some irregular white marks. Forelimbs ventrally brown with a longitudinal white stripe along ulna, dorsally brown. Hind limbs like dorsum.

Variation of color patterns ()

Dorsal surfaces are predominately brown (ZSFQ 550) to dark brown (ZSFQ 2502), densely splashed with light brown (ZSFQ 550, 552), brownish-gray (ZSFQ 2502), or turquoise (ZSFQ 2504), with or without a cream to light brown middorsal line continuing along the posterior edge of hindlimbs. Flanks light brown (ZSFQ 550) to dark brown (ZSFQ 2502–2504) with scattered irregular marks white (ZSFQ 550–552) to light turquoise (ZSFQ 2502–2504). Venter yellowish-cream with minute speckling; throat with irregular brown marks (ZSFQ 550) to homogeneously brown (ZSFQ 345, 551, 552, 2502–2504).

In preservative, dorsum dark brown, with a cream middorsal line continuing along the posterior edge of hindlimbs; middorsal line weakly defined in ZSFQ 550. Venter cream (ZSFQ 550–551, 2502) to brownish cream (ZSFQ 552, 2504); throat brown or cream with brown marks (ZSFQ 550).

Osteology of hands and feet

The hand and foot phalangeal formula are standard: 2-2-3-3 and 2-2-3-4-3, respectively (). The relative length of fingers is: I < II < IV < III, and that of toes is: I < II < V < III < IV. The carpus is composed of a radiale, ulnare, Carpal 1, and a large postaxial element assumed to represent a fusion of Carpals 2, 3, and 4 (). The prepollex is composed of one proximal bone and an elongated distal cartilage. The terminal phalanges are slightly T-shaped. The prehallux is represented by a small, rounded, proximal bone, and a distal irregular element ().

Call description ()

Advertisement calls were recorded 22:00 h on 9 April 2017 (air temperature not recorded). Adult male ZSFQ 2502 (recording code: LBE-C-049). The call sounds like a short chirp. Each call is composed by a single short, pulsed note, with a duration of 0.032–0.044 s (mean = 0.039 ± 0.005; n = 4). Each note has about 10 to 15 pulses, which are difficult to differentiate. Time between calls is 22.5–31.7 s (mean = 26.6 ± 4.681; n = 3). The dominant frequency is located at a relatively wide range at 3,363–4,172 Hz. One harmonics is present at 7,399–7,695 Hz (n = 4).Distribution and Natural History

Noblella worleyae is a leaf litter specialist and has only been found in either primary forest or moderately disturbed old growth secondary forest. It has been recorded from six nearby localities within the Río Manduriacu Reserve, Cantón Cotacachi, Imbabura province, Ecuador, at elevations between 1,184 m and 1,701 m (). Surveys conducted on the east side of the Río Mandiracu (opposite from the reserve) as well as those in and around the community of Santa Rosa de Manduriacu (ca. 3 km south of Río Manduriacu Reserve boundary) have yielded no records, although survey effort outside of the reserve is less extensive than that within the reserve. We have made eight field trips between 2012 and 2019, with 59 effective field days, with an average of five people actively searching for amphibians and we have been able to find a total of seven individuals. The new species seems to be endemic to this region, which is an area with high diversity and endemism of anurans [Citation14,Citation41]. The habitat ecosystem corresponds to Low Montane Evergreen Forest of western slopes of the Andes [Citation42]. The total restricted area that covers these localities is 389,248 m2.

Noblella worleyae is one of the few diurnal anurans at the Río Manduriacu Reserve. Calls were frequently heard from dawn (6:00 h) to dusk (19:00 h), but frogs stop vocalizing when approached. Individuals were found in areas with dense leaf litter and other decaying material, and at the base of large trees. The species is evasive and individuals quickly immersed between leaves and roots as an escape method. The new species is one of the more abundant amphibians at Río Manduriacu Reserve, as groups of individuals were frequently heard calling by day throughout much of the sloped reserve during expeditions. In fact, during a morning survey (6h20 am) a total of 13 males were heard calling along a 100-m transect (JBM, field notes). The new species did not call with heavy rain. During sampling days in April 2017, air temperature inside the forest was 12–26°C (thermometer placed 120 cm above ground level at the base of a tree). Individuals have also been observed after sunset while conducting night transects, as sampling in October 2016, and January–February, 2018, yielded eight records between 20:00 and 23:05 h. However, these individuals were presumably flushed from their resting place within the leaf litter as surveyors passed by.

Etymology

The specific name is a noun in the genitive case and is a patronym for Dr. Elizabeth K. Worley (1904–2004), Professor in the Biology Department at Brooklyn College, naturalist, science communicator, educator, and mentor.

Discussion

Our phylogeny shows similar relationships within the genus Noblella as those inferred in previous studies [Citation4,Citation6–8]. Noblella is a non-monophyletic taxon, as the genera Noblella and Psychrophrynella are nested and because the northern Noblella do not share the most recent common ancestor with the southern clade of Noblella and Psychroprynella. Further studies are necessary to solve the polyphyly of the genus, especially with the inclusion of genetic topotypical material of Noblella peruviana and Psychrophrynella bagrecito. The description of this new species adds to our understanding of the phylogenetic relationships within Noblella and the changes needed to render Noblella monophyletic.

The description of this new frog species from the Río Manduriacu Reserve is yet another study demonstrating the importance of the reserve as a critical conservation area for amphibian diversity [Citation14]. However, the expansion of large-scale mining concessions in northwestern Ecuador is a major threat to the future of this region [Citation14,Citation43]; illegal mining activities have been conducted within Río Manduriacu Reserve, as well as nearby areas [Citation14,Citation44]. The western Andean slopes of Ecuador is comprised of important micro-regions of small vertebrate endemism, which are restricted to areas with good-quality forest and with little to no anthropogenic activity (e.g [Citation14,Citation45,Citation46,Citation47]). Thus, projects that threaten these Andean forests must be regulated and authorized within the framework of the Ecuadorian Constitution. Moreover, a program for conservation actions aiming to protect the unique biodiversity is also needed for the Ecuadorian Andes. Such an approach is already being advanced, mostly with the participation of non-profit institutions that aim to protect priority and vulnerable forests for biodiversity conservation, such as the EcoMinga Foundation [Citation4,Citation14,Citation15]. Nonetheless, ongoing research, long-term conservation funding, and assurance that protected areas will not be undermined by extractive companies are necessary to ensure the survival of species with high endemism such as N. worleyae and its fragile habitats.

Author contributions

Carolina Reyes-Puig performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Ross Maynard performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Scott Trageser performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

José Vieira performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Paul Hamilton is Executive Director of The Biodiversity Group, which initiated herpetofauna study at Manduriacu. He obtained funding for fieldwork and lab work, developed field survey protocols, supervised fieldwork, contributed to fieldwork, approved the final draft.

Ryan L. Lynch performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Sebastián Kohn: Fieldwork planning, logistics and funding, present and active at both expeditions where individuals were collected, specimen transportation, acquisition of legal paperwork for specimen transportation, approved the final draft.

Jaime Culebras performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Jorge Brito performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Juan M. Guayasamin performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14 KB)Acknowledgments

Field work was funded by the Biodiversity Group, Fundacion Condor Andino, Fundacion EcoMinga, Sociobosque, USFQ. Work by Carolina Reyes-Puig was supported by Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ (projects HUBI ID 48 “Taxonomía, Biogeografía y Conservación de Anfibios y Reptiles”; HUBI ID 12268 “Taxonomía y Conservación de ranas terrestres en los páramos, estribaciones y tierras bajas del Ecuador”; HUBI ID 12253 “Descubre Napo”). Juan Manuel Guayasamin’s research is supported by Universidad San Francisco de Quito (Collaboration Grants 5521, 5467, 5447, 11164, Fondos COCIBA and Fondos Semilla Biosfera).

This study was developed as part of “Proyecto Descubre Napo”, an initiative of Universidad San Francisco de Quito in association with Wildlife Conservation Society, and funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, as part of the project: WCS Consolidating Conservation of Critical Landscapes (mosaics) in the Andes.

We conducted this research under collection permits N° 019-2018-IC-FAU-DNB/MAE, and agreement for access to genetic resources MAE-DNB-CM-2018-0106, issued by the Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador. We thank Stephanie Fogel for her generous support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barbour T. A list of Antillean reptiles and amphibians. Zoologica. 1930;11:61–116.

- Frost DR Amphibian species of the world: an online reference. Version 6.0. New York (USA): American Museum of Natural History; 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 21]. Available from: http://research.amnh.org/vz/herpetology/amphibia/

- Duellman WE, Lehr E. Terrestrial-breeding frogs (Strabomantidae) in Peru. Münster, Germany: Nature und Tier Verlag; 2009.

- Reyes-Puig JP, Reyes-Puig C, Ron S, et al. A new species of terrestrial frog of the genus Noblella Barbour, 1930 (Amphibia: Strabomantidae) from the llanganates-sangay ecological corridor, Tungurahua, Ecuador. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7405.

- Hedges SB, Duellman WE, Heinicke MP. New world direct-developing frogs (Anura: Terrarana): molecular phylogeny, classification, biogeography, and conservation. Zootaxa. 2008;1737(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1737.1.1

- De la Riva I, Chaparro JC, Castroviejo-Fisher S, et al. Underestimated anuran radiations in the high Andes: five new species and a new genus of Holoadeninae, and their phylogenetic relationships (Anura: Craugastoridae). Zool J Linn Soc. 2017;182(1):129–172.

- Catenazzi A, Ttito A. Psychrophrynella glauca sp. n., a new species of terrestrial-breeding frogs (Amphibia, Anura, Strabomantidae) from the montane forests of the Amazonian Andes of Puno, Peru. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4444.

- De La Riva I, Chaparro JC, Padial JM. The taxonomic status of Phyllonastes Heyer and Phrynopus peruvianus (Noble) (Lissamphibia, Anura): resurrection of Noblella Barbour. Zootaxa. 2008;1685(1):67.

- Guayasamin JM, Terán-Valdez A. A new species of Noblella (Amphibia: Strabomantidae) from the western slopes of the Andes of Ecuador. Zootaxa. 2009;2161(1):47–59.

- Lynch J. New species of minute Leptodactylid frogs from the Andes of Ecuador and Peru. J Herpetol. 1986;20(3):423.

- Heinicke MP, Lemmon AR, Lemmon EM, et al. Phylogenomic support for evolutionary relationships of New World direct-developing frogs (Anura: Terraranae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2018 Jan;118:145–155.

- De Queiroz K. Ernst Mayr and the modern concept of species. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2005;102(Supplement 1):6600–6607.

- De Queiroz K. Species concepts and species delimitation. Syst Biol. 2007;56(6):879–886.

- Guayasamin JM, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Vieira J, et al. A new glassfrog (Centrolenidae) from the Choco-Andean Rio Manduriacu Reserve, Ecuador, endangered by mining. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6400.

- Reyes-Puig C, Pablo Reyes-Puig J, Velarde-Garcez D, et al. A new species of terrestrial frog Pristimantis (Strabomantidae) from the upper basin of the Pastaza River, Ecuador. Zookeys. 2019;832:113–133.

- Reyes-Puig C, Bittencourt-Silva GB, Torres-Sánchez M, et al. Rediscovery of the endangered Carchi Andean Toad, Rhaebo colomai (Hoogmoed, 1985), in Ecuador, with comments on its conservation status and extinction risk. Check List. 2019;15(3):415–419.

- Guayasamin JM, Castroviejo-Fisher S, Ayarzaguena J, et al. Phylogenetic relationships of glassfrogs (Centrolenidae) based on mitochondrial and nuclear genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008 Aug;48(2):574–595.

- Padial JM, Grant T, Frost DR. Molecular systematics of terraranas (Anura: Brachycephaloidea) with an assessment of the effects of alignment and optimality criteria. Zootaxa. 2014 Jun;26(3825):1–132.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780.

- Maddison DR, Maddison WP. MacClade 4. release version 4.07 for OSX. USA: Sinauer Sunderland Massachusetts; 2005.

- Zwickl DJ. GARLI: genetic algorithm for rapid likelihood inference. Texas (USA); 2006. The University of Texas at Austin.

- Taylor WR, Van Dyke GC. Revised procedures for staining and clearing small fishes and other vertebrates for bone and cartilage study. Cybium. 1985;9:107–109.

- Duellman WE, Trueb L. Biology of amphibians. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1994.

- Fabrezi M. El carpo de los anuros. Alytes. 1992;10:1–29.

- Fabrezi M. The anuran tarsus. Alytes. 1993;11:47–63.

- Trueb L. Bones, frogs, and evolution. In: Vial JL, editor. Evolutionary biology of the anurans: contemporary research on major problems. (pp. 65–132). Columbia (USA): University of Missouri Press; 1973.

- Trueb L. The skull: patterns of structural and systematic diversity: patterns of cranial diversity among the Lissamphibia. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1993.

- Ruf J. RAVEN: real-time analyzing and verification environment. J Universal Comput Sci. 2001;7(1):89–104.

- Köhler J, Jansen M, Rodríguez A, et al. The use of bioacoustics in anuran taxonomy: theory, terminology, methods and recommendations for best practice. Zootaxa. 2017;4251(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4251.1.1.

- Lehr E, Aguilar C, Lundberg MA. A New species of Phyllonastes from Peru (Amphibia, Anura, Leptodactylidae). J Herpetol. 2004;38:214–218.

- Duellman WE. A new species of leptodactylid frog, genus Phyllonastes, from Peru. Herpetologica. 1991;47:9–13.

- Lehr E, Catenazzi A. A New species of minute Noblella (Anura: strabomantidae) from southern Peru: the smallest frog of the Andes. Copeia. 2009;2009(1):148–156.

- Catenazzi A, Ttito A. Noblella thiuni sp. n., a new (singleton) species of minute terrestrial-breeding frog (Amphibia, Anura, Strabomantidae) from the montane forest of the Amazonian Andes of Puno, Peru. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6780.

- De la Riva I, Kohler J. A new minute Leptodactylid frog, Genus Phyllonastes, from humid montane forests of Bolivia. J Herpetol. 1998;32:325.

- Lynch JD. Two new species of frogs of the genus Euparkerella (Amphibia: leptodactylidae) from Ecuador and Perú. Herpetologica. 1976;32:48–53.

- Santa-Cruz R, von May R, Catenazzi A, et al. A New Species of Terrestrial-Breeding Frog (Amphibia, Strabomantidae, Noblella) from the Upper Madre De Dios Watershed, Amazonian Andes and Lowlands of Southern Peru. Diversity. 2019;11(9). DOI:https://doi.org/10.3390/d11090145.

- Harvey MB, Almendariz A, Brito MJ, et al. A new species of Noblella (Anura: craugastoridae) from the amazonian slopes of the Ecuadorian Andes with comments on Noblella lochites (Lynch). Zootaxa. 2013;3635:1–14.

- Noble GK. Five new species of Salientia from South America. Am Mus Novit. 1921;29:1–7.

- Catenazzi A, Uscapi V, von May R. A new species of Noblella (Amphibia, Anura, Craugastoridae) from the humid montane forests of Cusco, Peru. Zookeys. 2015;516(516):71–84.

- Köhler J. A new species of Phyllonastes Heyer from the Chapare region of Bolivia, with notes on Phyllonastes carrascoicola. Spixiana. 2000;23:47–53.

- Hutter CR, Guayasamin JM, Wiens JJ. Explaining Andean megadiversity: the evolutionary and ecological causes of glassfrog elevational richness patterns. Ecol Lett. 2013 Sep;16(9):1135–1144.

- MAE. Sistema de clasificación de los ecosistemas del Ecuador continental. Quito: Subsecretaría de Patrimonio Natural; 2012.

- Roy BA, Zorrilla M, Endara L, et al. New mining concessions could severely decrease biodiversity and ecosystem services in Ecuador. Trop Conserv Sci. 2018;11:1–20.

- Lynch RL, Kohn S, Ayala-Varela F, et al. Rediscovery of Andinophryne olallai Hoogmoed, 1985 (Anura, Bufonidae), an enigmatic and endangered Andean toad. Amphibian Reptile Conserv. 2014;8(1).

- Yánez-Muñoz MH, Reyes-Puig CP, Bejarano-Muñoz P, et al. Otra nueva especie de rana Pristimantis (Anura: terrarana) de las estribaciones occidentales del Volcán Pichincha, Ecuador. Av en Cienc e Ing. 2015;7(2). DOI:https://doi.org/10.18272/aci.v7i2.257.

- Yánez-Muñoz MH, Reyes-Puig C, Reyes-Puig JP, et al. A new cryptic species of Anolis lizard from northwestern South America (Iguanidae, Dactyloinae). Zookeys. 2018;794:135–163.

- Maynard RJ, Trageser SJ, Kohn S, et al. Discovery of a reproducing population of the Mindo Glassfrog, Nymphargus balionotus (Duellman, 1981), at the Río Manduriacu Reserve, Ecuador, with a literature review and comments on its natural history, distribution, and conservation status. Amphibian Reptile Conserv. 2020;14(2):172–184

Appendix I

Noblella coloma: Ecuador: Pichincha: QCAZ 7277, 7412, 8701, 11,614, 26,307, 32,702, Reserva Ecológica Río Guajalito; 1800–2000 m. Noblella heyeri: Ecuador, Loja: QCAZ 31,470, 31,471, 31,473, Loja–Zamora road; 2385 m, QCAZ 22,501, Zamora-Huaico; 2000 m. Noblella lochites: Ecuador, Napo: ZSFQ 346, Archidona, Reserva Narupa, 1176 m; ZSFQ 347, Reserva Narupa, 1152 m; ZSFQ 348, Reserva Narupa, 1167 m; Zamora Chinchipe: ZSFQ 1119, Yantzaza, Concesión La Zarza, 1385 m; ZSFQ 1124, Concesión La Zarza, 1357 m; ZSFQ 1186, ZSFQ 1187, ZSFQ 1188, Yantzaza, Río Blanco, 1654 m; ZSFQ 1188, Río Blanco, 1830 m. Noblella cf. lochites: Ecuador, Zamora Chinchipe: ZSFQ 3262–326, Yantzaza, Estación Experimental El Padmi UNL, 775 m. Noblella myrmecoides: Ecuador, Napo: ZSFQ 670, Mera, Parque Nacional Llanganates, 1325 m; ZSFQ 671, Parque Nacional Llanganates, 1352 m; ZSFQ 672, Parque Nacional Llanganates, 1327 m. Noblella cf. myrmecoides: Ecuador, Tungurahua: ZSFQ 1341, Río Negro, Reserva Río Zuñag, 1269 m.