ABSTRACT

In 2008, Ecuador recognized the Constitutional Rights of Nature in a global first. This recognition implies a major shift in the human-nature relationship, from one between a subject with agency (humans) and an exploitable object (nature), to a more equilibrated relationship. However, the lack of a standard legal framework has left room for subjective interpretations and variable implementation. The recent widespread concessioning of pristine ecosystems to mining industries has set up an unprecedented conflict and test of these rights. Currently, a landmark case involving Los Cedros Protected Forest and mining companies has reached the Constitutional Court of Ecuador. If Ecuador’s highest Court rules in favor of Los Cedros and the Rights of Nature, it would set a legal precedent with enormous impact on biological conservation. Such a policy shift offers a novel conservation strategy, through citizen oversight and action. A ruling against Los Cedros and the Rights of Nature, while a major setback for biodiversity conservation, would be taken in stride by the active social movement supporting these goals, with the case likely moving into international courts. Meanwhile, extractive activities would continue and expand, with known consequences for biodiversity.

Introduction

Legislation has the potential to influence human practices [Citation1] and we are currently witnessing a conceivable tipping point in the relationship between law and biodiversity conservation. Fittingly, this is taking place in front of the Constitutional Court of Ecuador, one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth [Citation2] and the only one that grants rights for all of Nature at a constitutional level [Citation3].

Biodiversity (populations, species, and ecosystems) is facing threats from numerous human activities, and legislation usually falls short by having a narrow view and application, often limiting protection to endangered species. Under these scenarios, the legal framework that the Rights of Nature provide is a novel opportunity for biodiversity conservation, as well as citizen oversight and action.

Rights of Nature

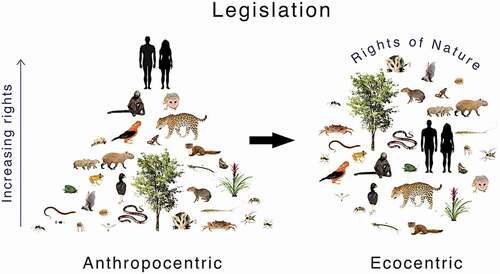

Recognizing Nature as a legal entity with rights denotes a shift in the human-nature relationship, from one between a subject with agency (humans) and an exploitable object (Nature), to a relationship of mutual respect and tolerance [Citation3–5] (). Articles 71–74 of the Ecuadorian Constitution [Citation3] define the Rights of Nature to respect, restoration, protection, and enjoyment, explicitly stating that Nature has the right to “integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions, and evolutionary processes (Art. 71).” While all of the rights laid out in these articles are designed to protect Nature and the human populations that depend on it, Article 73 is of specific importance for the persistence of biodiversity. The first paragraph of Article 73 declares that “the State will apply preventive and restrictive measures on all activities that can lead to the extinction of species, the destruction of ecosystems or the permanent alteration of natural cycles.”

Figure 1. Recognizing that Nature has rights denotes a shift in the human-nature relationship, from one between a subject with agency (humans) and an exploitable object (Nature), to a relationship of mutual respect and tolerance, towards permanent coexistence

The most important achievement of Article 73 is the constitutional recognition that Nature is no longer an object from the point of view of the Law, but an entity with its own rights [Citation3]. Furthermore, Article 10 establishes that Nature will have the rights that are recognized in the Constitution. The Constitution also tasks Ecuadorian citizens with the responsibility of respecting and looking after the Rights of Nature, as well as preserving a healthy environment (Article 83.6) [Citation3].

Under many environmental laws the elements of Nature are considered property, and hence resources to exploit, whereas Rights of Nature imply a goal of thriving, healthy ecosystems and human societies (). The difference is significant: environmental law treats Nature as an object and determines, for example, how much a human or human enterprise can pollute water. In contrast, under a Rights of Nature perspective, pollution should be avoided altogether because it affects the core of Nature’s rights. Nature cannot represent itself; it needs a voice, legal guardians, and a seat at the negotiating table. Hence, the second paragraph of Article 71 in Ecuador’s Constitution says that “all persons, communities, peoples, and nations can call upon public authorities to enforce the Rights of Nature.”

Conflict with extractive industries: the case of Los Cedros protected forest

Extractive industries, including mining and oil projects, cause serious biodiversity loss and environmental conflicts that are widespread in Latin America [Citation6–8]. In addition to the direct impacts of mining, this industry is also a significant driver of deforestation. Clearing native forests for mineral exploration and extraction, and building new roads, opens new access to lands for colonization, hunting, and further forest clearing by settlers [Citation6,Citation7,Citation9]. Mining in areas with high precipitation, such as tropical mountains, has damaged freshwater ecosystems with harms including erosion and excessive sediment loading and extremely high levels of heavy metal contamination [Citation10–12].

In the last two years, there has been an escalating conflict between mining companies (the Canadian Cornerstone Capital Resources and its Ecuadorian partner ENAMI) and the megadiverse Los Cedros Protected Forest (hereafter Los Cedros). Los Cedros was officially designated as a protected forest (Bosque Protector) in 1994; it is within the buffer zone of the Cotacachi Cayapas National Park and represents one of the last remnants of primary forest that once occurred in the Northwestern Andes of Ecuador. Protected forests such as Los Cedros are registered as one category within the governmental system of protected areas in Ecuador; they can be privately or publicly owned, but within their boundaries land use is restricted to certain activities that are explicitly agreed upon as a condition of their entry into official protected status. These conditions do not typically list mineral exploration as permitted, and in the case of Los Cedros, explicitly disallow it. Recognition by the government enables legal support when conflicts in land use occur [Citation13].

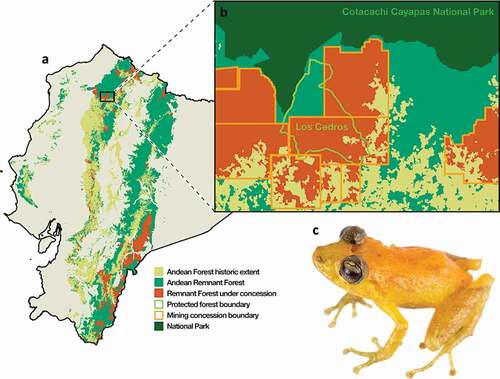

An estimated 500 species of trees exist in just the southeastern portion of Los Cedros that has been surveyed, an area less than 1000 hectares (data available on request); this can be compared to 454 tree species in all of Europe (1.018 billion hectares) [Citation14]. The cloud forest of Los Cedros contains at least 242 species at some risk of extinction according to the Ecuador Red Lists; of these, 149 are also on the IUCN Red List (Table S1). Several species known only from Los Cedros or its immediate surroundings face likely extinction if mining is allowed, including the Los Cedros rainfrog (Pristimantis cedros) and at least 12 orchid species [Citation15–17] (, Table S1). In addition to its incredible diversity, this protected forest supports many ecological functions and ecosystem services. The human settlements around Los Cedros rely on these ecosystem services for a variety of livelihoods including, sustainable agriculture (e.g. organic coffee), community-based ecotourism, and small-scale reforestation, promoting the protection of headwater streams. These sustainable practices have increased in the last 20 years [Citation18]. If mining is endorsed, the trend towards local sustainable practices may be lost.

Figure 2. Conflict between mining activities and biodiverse ecosystems. (A) Remnant native Andean forest in Ecuador (green; data from the Ecuadorian Ministry of Environment), showing deforestation on the western slope of the Andes (yellow), and overlap between remnant forest and current mining concessions (red; data from the Ecuadorian Agency for the Control and Regulation of Mines). (B) Inset, showing the area around Los Cedros; note the overlap between mining concessions and remnant forests. (C) The Los Cedros rainfrog (Pristimantis cedros) is one of hundreds of known endemic and endangered species documented from Los Cedros (Table S1). This frog is only known from Los Cedros and the nearby Río Manduriacu Reserve, areas concessioned to two mining companies (the Canadian Cornerstone Capital Resources, and the Anglo-Australian BHP Billiton)

Ecuador’s forward thinking Constitution has been a theoretical exercise, until now. Many constitutional provisions with regards to the Rights of Nature have not been effectively enforced and at times have been willfully ignored. Ecuadorian and international scientists and advocates have taken on the case of mining concessions in Los Cedros and worked through the lower courts to protect the biodiversity and associated ecosystem services of this remarkable region (SI Appendix). Now the case is before the Constitutional Court and represents a true test of the “Rights of Nature” articles of the Constitution. The Court is expected to pronounce its verdict during the coming months.

Regional and global implications for conservation

If Ecuador’s Constitutional Court rules in favor of Los Cedros, it would set a legal precedent with enormous positive impact for biological conservation in Ecuador, Latin America, and, potentially, the world.

In Ecuador, recent mining concessions cover more than 13% of Ecuador’s territory, often overlapping with the last remnants of megadiverse Andean tropical forests, more than two million hectares of which were thought to be preserved due to having protected forest designation [Citation16] (). With an ongoing, regional economic crisis exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries have, in practice, relaxed environmental standards in favor of extractive activities [Citation19,Citation20]. Under this situation, numerous local communities and NGOs have come forward to protect the forests and the ecosystem services that they provide. A ruling favoring Los Cedros would be a powerful precedent that will surely trigger similar actions towards the protection of endangered ecosystems across the country, creating, for the first time, a possibility of real and effective citizen action towards environmental enforcement. Additionally, the Constitutional Court of Ecuador has selected the case of Los Cedros as one for the development of jurisprudence in the country; thus, the resolution by the Court in this particular case will influence further similar processes.

At the regional scale, political and economic pressures around these issues in Latin America are extremely strong, and there are similar ongoing conflicts between extractive industry and diminishing ecosystems in several neighboring countries. Legal innovations around the Rights of Nature are currently being explored elsewhere in the region (e.g. Colombian courts have recently extended rights to certain river systems in that country) [Citation21]. The precedent set by the Los Cedros case will likely influence social and environmental activists from other countries to work towards similar views on the Rights of Nature in their corresponding legal systems. Expansion and recognition of the Rights of Nature throughout Latin America could also be a tool of social justice, as it legitimizes the ongoing efforts of citizens and indigenous groups to defend Nature as a subject of the law.

At the global level, a ruling in favor of the Rights of Nature would set an example that could be followed by other countries or intergovernmental organizations. There is already a signature campaign and civil society initiative pushing the United Nations to adopt a “Declaration for the Rights of Mother Earth”, calling countries to be the champions for this initiative. It is important for the world to reflect on the limits of Nature and to seriously question the effectiveness of current conservation policies and actions. Policy frameworks that place humans in context as a part of Nature, integrated into a system that balances intrinsic rights between legitimate subjects of the Law, rather than placing humans as above, or apart from, Nature, will be a necessary part of addressing the serious environmental issues that our planet is facing.

In contrast, a ruling against Los Cedros and the Rights of Nature will represent a major setback for biodiversity conservation and, most likely, will be followed by a swift expansion of extractive activities, especially mining. Under this scenario, from the legal stand view, environmental lawyers will take the case to international courts, a process that would take several years until a final resolution is reached. Nevertheless, even under this pessimist setting, alternative venues are viable, especially the work of local communities and indigenous people towards their right to vote for or against extractivism in their territories (i.e. environmental democracy) [Citation22].

To conclude, there is a pressing need to establish stronger and more effective conservation strategies. Developing legislation that actually allow the protection of nature as established in the Constitution is one such strategy, which may be particularly effective because it would empower citizens and communities to act as stewards and guardians of Nature. Also, Rights of Nature need to be accompanied by a strengthening of local institutions that, in conjunction with local communities, can assume the responsibility of actually making these legal rights a reality [Citation21]. Given the rates of deforestation and the realities of global climate change, the need for such a policy shift is now more urgent than ever [Citation8,Citation19,Citation20],´As this article was in production, the Constitutional Court of Ecuador ruled in favor of Los Cedros.´

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (122.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank Mary E. Powers, Patricia Salerno, Gabriel Massaine Moulatlet, and an anonymous reviewer for their comments on the manuscript. J.M.G. acknowledges support from Universidad San Francisco de Quito (HUBI 16808, 16871). B.R.T acknowledges support from Universidad de Las Américas, Ecuador (AMB.BRT.19.02). Photos in were provided by Jose Vieira/Ex-Situ/Tropical Herping. Photo in was provided by Jaime Culebras.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

References

- Friedman LM. Impact: how law affects behavior. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: Harvard University Press; 2016.

- Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, and Wilson EO. Megadiversity: earth’s biologically wealthiest nations. Mexico: CEMEX/Agrupación Sierra Madre; 2005.

- Montecristi Asamblea Constituyente. Constitución de la República del Ecuador; 2008 doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2019.1654544.

- Laastad SG. Nature as a subject of rights? National discourses on Ecuador’s constitutional rights of nature. Forum Dev Stud. 2019;0:1–25.

- Kotzé LJ, Villavicencio-Calzadilla P. Somewhere between rhetoric and reality: environmental constitutionalism and the rights of nature in Ecuador. Transnatl Environ Law. 2017;6(3):401–433 doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102517000061.

- Alvarez-Berríos NL, Aide TM. Global demand for gold is another threat for tropical forests. Environ Res Lett. 2015;10(1):014006 doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/1/014006.

- Lessmann J, Fajardo J, Muñoz J, et al. Large expansion of oil industry in the Ecuadorian amazon: biodiversity vulnerability and conservation alternatives. Ecol Evol. 2016;6(14):4997–5012 doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2099.

- Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature. 2012;486(7401):59–67 doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148.

- Lessmann J, Troya MJ, Flecker AS, et al. Validating anthropogenic threat maps as a tool for assessing river ecological integrity in Andean-Amazon basins. Peer J. 2019;7:e8060 doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8060.

- Wantzen K, Mol J. Soil erosion from agriculture and mining: a threat to tropical stream ecosystems. Agriculture 2013;3(4):660–683 doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture3040660.

- Capparelli MV, Massaine Moulatlet G, Moledo de Souza Abessa D, et al. An integrative approach to identify the impacts of multiple metal contamination sources on the Eastern Andean foothills of the Ecuadorian Amazonia. Sci Total Environ. 2020;709:136088 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136088.

- Galarza E, Cabrera M, Espinosa R, et al. Assessing the quality of Amazon aquatic ecosystems with multiple lines of evidence: the case of the northeast Andean foothills of Ecuador. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2021;107(1):52–61 doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-020-03089-0.

- Horstman E. Establishing a private protected area in Ecuador: lessons learned in the management of Cerro Blanco protected forest in the city of Guayaquil. 2017; Case Stud Environ. 1:1–14 doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/cse.2017.sc.452964.

- Rivers M, Beech E, and Bazos L, . . European Red List of Trees (Cambridge, UK, and Brussels, Belgium: IUCN). 2019 viii + 60pp 978-2-8317-1985-6 (PDF) 978-2-8317-1986-3 (print) doi:https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH2019.ERL.1.en.

- Endara L, Hirtz A, and Jost L, et al. Orchidaceae. In: León-Yánez S, Eds. Libro Rojo de las Plantas Endémicas del Ecuador. Quito: Herbario QCA, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador; 2011. p. 441–702.

- Roy BA, Zorilla M, Endara L, et al. New mining concessions could severely decrease biodiversity and ecosystem services in ecuador. Trop Conserv Sci. 2018;11:1–20 doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082918780427.

- Hutter CR, Guayasamin JM. Cryptic diversity concealed in the Andean cloud forests: two new species of rainfrogs (Pristimantis) uncovered by molecular and bioacoustic data. Neotrop Biodivers. 2015;1(1):36–59 doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23766808.2015.1100376.

- D’Amico L El Agua es Vida/water is life: community watershed reserves in intag, ecuador, and emerging ecological identities Johnston, BR, Hiwasaki, L, Klaver, IJ, Ramos Castillo, A, Barber, M, Niles, D, and Strang, V. In: Water, cultural diversity, and global environmental change. Springer (Netherlands) and UNESCO (Jakarta): Springer; 2012. p. 433–452 doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1774-9.

- Daly DC. We have been in lockdown, but deforestation has not. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(40):24609–24611 doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2018489117.

- Roche B, Guégan JF. Ecosystem dynamics, biological diversity and emerging infectious diseases. C R Biol. 2011;334(5–6):385–392 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvi.2011.02.008.

- Wesche P. Rights of nature in practice: a case study on the impacts of the Colombian atrato river decision. J Environ Law. 2021;0:1–26 doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqab021.

- Ricci V. Environmental democracy in Ecuador promotes anti-mining agenda. Mongabay. 2020Nov9; Available fromhttps://news.mongabay.com/2020/11/environmental-democracy-in-Ecuador-promotes-anti-mining-agenda/