Abstract

Microturbellarians are all mostly small free-living Platyhelminthes that do not belong to either the Polycladida or Tricladida order. This group includes species of the clades Catenulida and Rhabditophora. Species of microturbellarians are known to live in marine and continental waters such as rivers, where they are diverse and abundant. However, there are few records of microturbellarians in most of the rivers of the Pacific slope of Peru. Here, we report eight species of microturbellarians from the Chillón River, in the central region of Peru. Of the total species recorded, five (Gieysztoria cuspidata, G. bellis, Myostenostomum vanderlandi, Stenostomum tuberculosum and S. saliens) represent the first reports on the Pacific slope of the Neotropical region in Peru, thereby increasing the diversity of microturbellarians in this country.

Introduction

Catenulida and Rhabditophora are the clades of Platyhelminthes containing species of microturbellarians that are generally short in length [Citation1,Citation2]. The genital systems of some species of these hermaphroditic flatworms are important for species identification, with the male copulatory apparatus containing sclerotic stylets, spines and/or cirrus [Citation3]. These organisms live in different environments such as marine, brackish and freshwater (rivers, lagoons and temporary pools) habitats [Citation3–6]. They have also been found in moist environments (e.g. moss, vascular plants, wood snags, detritus, gravel, or sand) [Citation7].

Most records of freshwater microturbellarians in the Neotropical region are from Brazil (the states of São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná) and Argentina (the provinces of Santa Fé, Buenos Aires and Entre Ríos) [Citation2,Citation8–26]. In Peru, there have been sporadic approaches to study freshwater microturbellarians. To date, 31 species belonging to Catenulida, Macrostomorpha and Rhabdocoela have been reported living in the Amazon floodplain (Loreto and Ucayali regions), altitudinal lagoons (Junín and Puno regions), brackish ponds of different sizes and depths (Lima region), and a few rivers from the Pacific slope (Lima region) () [Citation5,Citation22,Citation24,Citation27–30]. In addition, microturbellarians in Peru are scarcely taken into account when assessing freshwater invertebrate fauna [Citation5]. This lack of reports is due to the need to study these organisms alive whenever possible in order to identify diagnostic structures to help specific identification [Citation3,Citation31], and most importantly because of the lack of specialists in the field.

Figure 1. Localities sampled where species of microturbellarians are found in Peru. A) Species included in this study, B) species from du Bois-Reymond Marcus [Citation28], C) species from Reyes & Brusa [Citation5], D) species from Reyes et al. [Citation30], E) species from Noreña et al. [Citation29,Citation34] and Damborenea et al. [Citation22], F) species from Damborenea et al. [Citation24], and G) species from Beauchamp [Citation27].

![Figure 1. Localities sampled where species of microturbellarians are found in Peru. A) Species included in this study, B) species from du Bois-Reymond Marcus [Citation28], C) species from Reyes & Brusa [Citation5], D) species from Reyes et al. [Citation30], E) species from Noreña et al. [Citation29,Citation34] and Damborenea et al. [Citation22], F) species from Damborenea et al. [Citation24], and G) species from Beauchamp [Citation27].](/cms/asset/af109cfc-96ba-4bd3-b1cb-0fdb17138a37/tneo_a_2040348_f0001_oc.jpg)

With the aim of increasing the knowledge of the microturbellarian fauna, we surveyed a hydrographic basin in the center of Peru, the Chillón River. Photographs and schematic representations of the species reported are shown to facilitate recognition in subsequent assessments in other hydrographic basins.

Material and methods

The study area was the Chillón River, between the provinces of Lima and Canta, in the central region of Peru. This river flows from east to west for about 126 km (11°22ʹS–11°56ʹS; 76°26ʹW–77°08ʹW), originating in the Viuda mountain range (~4500 meters above sea level [m.a.s.l]) and flowing towards the Pacific Ocean [Citation32] (). Samples from the riverbanks at an altitude of ~500 m.a.s.l were taken almost monthly from February 2013 to November 2017. The sites sampled were characterized by muddy substrates and stones, with herbaceous vegetation and algae. Water temperature and pH of each locality were measured.

Microturbellarians were collected from aquatic herbaceous vegetation and algae using a net with a mesh size of 80 µm, and the samples were carried alive to the laboratory. All specimens were measured and described based on external and internal characteristics. Some microturbellarians were relaxed using MgCl2 7% and examined under light microscopy. When sclerotic structures (e. g. copulatory stylets) were observed, whole-mounted preparations were performed using polyvinyl-lactophenol. Stylets and soft body tissues were measured in micrometers (μm) using the ImageJ software [Citation33]. The material studied was deposited in the Departamento de Protozoología, Helmintología e Invertebrados Afines, Museo de Historia Natural (MUSM), Peru. Some specimens deteriorated during the observations were not deposited.

Abbreviations used in the figures

ab: anterior brain lobe; ap: adhesive papilla; cp: ciliated pit; e: eyes; eg: egg; ep: excretophores; fg: female gonopore; gd: girdle; ger: germovitellarium; i: intestine; m: mouth; mgu: muscular gut; np: nephridiopore; o: ovary; pb: posterior brain lobe; ph: pharynx; phg: pharyngeal glands; pi: pigmentation; pr: protonephridium; pv: prostatic vesicle; rb: light-refracting bodies; sm: septum; sp: spines; sv: seminal vesicle; t: testes; u: uterus; v: vitellaria.

Results and remarks

Systematics

Catenulida Meixner, 1924

Stenostomidae Vejdovsky, 1880

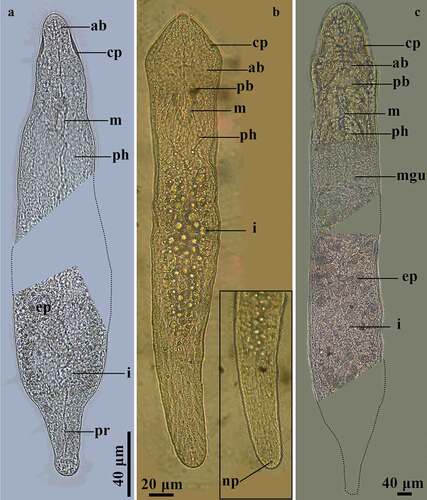

Stenostomum grande Child, 1902 ()

Figure 2. Stenostomum grande Child, 1902. A, Photograph of a live specimen; B, Schematic representation of the habitus; C, Detail of the anterior region of the body; D, Detail of the region of the pharynx; E, Detail of the caudal region of the body.

Material studied

Observations of live individuals, three of which were studied in squashed preparations.

Locality sampled

Chillón River (11°44ʹ1.8”S; 76°58ʹ19.56”W), near Trapiche in Canta Province, Lima region (2015/11/20) (temperature: 23.4 °C; pH: 8.2).

Other localities in Peru

Pacaya Samiria National Reserve in the Loreto region [Citation34].

Distribution

United States (US) [Citation35–37], Finland [Citation38], Poland [Citation39], Russia [Citation40, and references therein], Suriname [Citation41], Brazil [Citation13,Citation26], Peru [Citation34] and Argentina [Citation21].

Description and remarks

The color of the body is whitish, being darker in the intestinal region (). The body size of worms formed by two or three zooids ranges between 797 and 2404 μm long and 108–324 μm wide. The anterior and posterior brain lobes, light-refracting bodies, and pharyngeal glands, are characteristic of the species [Citation21] (). The body length of specimens from Peru is within the species range (730–2000 μm) [Citation12,Citation13,Citation21,Citation26,Citation36,Citation37].

Stenostomum saliens Kepner & Carter, 1931 ()

Material studied

A single individual, studied in a squashed preparation.

Locality sampled

Chillón River (11°44ʹ4.38”S; 76°58ʹ20.52”W), near Trapiche in Canta Province in the Lima region (2015/10/31) (temperature: 22.3 °C; pH: 7.2).

Distribution

US [Citation36,Citation37], Poland [Citation42], Suriname [Citation41], Brazil [Citation13,Citation26] and Argentina [Citation21].

Description and remarks

Live animal is yellow-whitish and fusiform. The body is 246.7 μm long and 45.7 μm wide; no zooids were observed. The anterior region has two small ciliated lateral pits, with six pairs of anterior brain lobes associated with these. Light-refracting bodies absent. The intestine has scarce excretophores with no particular arrangement, and the posterior region of the body is free of intestine. These characteristics are in accordance with the diagnosis of the species [Citation36]. The single-zooid specimen from Peru is similar in length to those found in Argentina (150–620 μm) [Citation21], but smaller than those in Poland (600–800 μm) [Citation42], USA (620 μm) [Citation36] and Brazil (400–600 μm) [Citation13,Citation26]. Interestingly, Kepner & Carter [Citation36] did not mention the presence of excretophores in the intestinal region, although Larsson & Willems [Citation43] reported that excretophores in Stenostomum saliens from Sweden are absent. Specimens from Peru present scarce excretophores, suggesting that these structures are a variable feature of the species. In addition, S. saliens has not previously been recorded in Peru, thereby expanding the distribution range of the species to the occidental coast of the Neotropical region.

Stenostomum tuberculosum Nuttycombe & Waters, 1938 ()

Material studied

Two individuals, studied in squashed preparations.

Locality sampled

Chillón River, Lima region (11°44ʹ1.8”S; 76°58ʹ19.56”W) (2013/04/18, 2013/10/26) (temperature: 23.6 °C; pH: 8.1).

Distribution

US [Citation37], Suriname [Citation41], Brazil [Citation13,Citation26], Argentina [Citation21], Finland [Citation44], Poland [Citation42] and Germany [Citation45].

Description and remarks

Single-zooid animals are whitish. The body is 475 μm long and 66 μm wide, is covered by long semi-rigid sensory cilia, which are more abundant at the anterior and posterior end of the body. The anterior tip of the body has a notorious tubercle. The intestine is lobulated, and the posterior body region is free of intestine. In comparison with single-zooid specimens found in other regions, animals from Peru are larger than those recorded by Nuttycombe & Waters [Citation37] (200 μm) and Marcus [Citation13] (200–500 μm). However, specimens of four zooids are larger than Peruvian worms [Citation13,Citation37], and those of two zooids are similar in length [Citation42,Citation44] or longer [Citation21]. The finding of S. tuberculosum, which represents the first report in Peru, expands its distribution to the occidental border of the Neotropical region.

Myostenostomum Luther, 1960

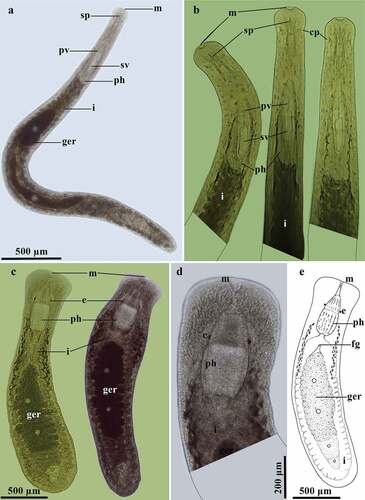

Myostenostomum vanderlandi Rogozin, 1992 ()

Material studied

Two individuals, one animal studied in squashed preparations.

Locality sampled

Chillón River, Lima region (11°44ʹ1.8”S; 76°58ʹ19.56”W) (2013/03/05) (temperature: 24.5 °C; pH: 8.4).

Distribution

Suriname [Citation41], Russia [Citation46] and Brazil [Citation26].

Description and remarks

Single-zooid animals are whitish in color. The body is 1103 μm long and 182 μm wide. The anterior brain lobe has 7 paired metameric ganglia. The posterior brain lobe has a triangular shape. The blind-sac intestine has a muscular belt, 78.6 μm long and 155.2 μm wide at its anterior portion. Excretophores are randomly arranged along the intestine. These features agree with the specimens of M. vanderlandi from Suriname [Citation41], Brazil [Citation26] and Russia [Citation46]. In addition, the body length of the individuals from Peru is within the range of the species (500–1300 μm) [Citation26,Citation41,Citation46]. This is the first record of M. vanderlandi in Peru.

Rhabdocoela Ehrenberg, 1831

Dalytyphloplanida Willems, Wallberg, Jondelius, Littlewood, Backeljau, Schockaert & Artois, 2006

Dalyelliidae Graff, 1905

Gieysztoria Ruebush & Hayes, 1939

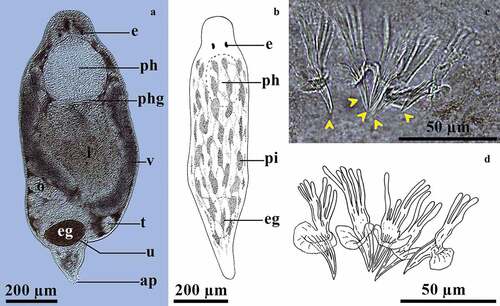

Gieysztoria cuspidata (Schmidt, 1861) Ruebush & Hayes, 1939 ()

Figure 4. Gieysztoria cuspidata (Schmidt, 1861) Ruebush & Hayes, 1939. A, Dorsal view of a squashed live animal showing its internal organs; B, Schematic representation of the habitus of a live swimming animal showing dorsal pigment; C, Penis stylet from a whole-mounted individual (yellow arrowheads indicate each spine); D, Schematic representation of the penis stylet with detail of the digitiform projections.

Material studied

Nine individuals observed alive, five of which were studied as whole-mounted specimens (MUSM-INV 4790–4794).

Locality sampled

Chillón River (11°43ʹ30.9”S, 76°57ʹ54.1”W; 11°44ʹ1.8”S, 76°58ʹ19.56”W; 11°43ʹ53.64”S, 76°58ʹ16.38”W) in temporary ponds, near the river, in Trapiche, Canta Province, Lima region (2015/6/8; 2015/7/23) (temperature: 24.1–25 °C; pH: 8.4–7.9).

Distribution

Broadly distributed in the Palearctic, Afrotropical and Nearctic regions [[Citation47], and references therein].

Description and remarks

Live mature animals are 900‒1600 μm long. The body has dark-brownish anastomosed dots () not mentioned in specimens studied in other regions [Citation48,Citation49]. In the male reproductive system, the globular seminal vesicle shows the same size as the prostatic vesicle. The penis stylet has five claw-like spines similar in length, with digitiform projections at the proximal region, without a real girdle. Each spine has a skirt-like projection for muscular insertion (). The tips of the spines are slightly curved outward. Spines are 20.5–32.1 µm long (48.5–56.7 µm long including the proximal digitiform projections). The egg is 252.7–164.8 µm long and 108.1–153 µm wide (). Two tubular brown-greenish vitellaria branches extend from the ventral posterior zone to the anterior dorsal zone, reaching the pharynx level (). This is the first record of Gieysztoria cuspidata in the Neotropical region.

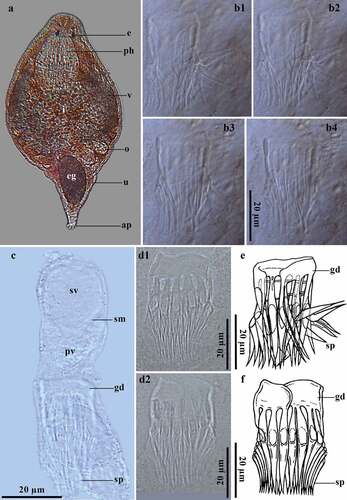

Gieysztoria bellis (Marcus, 1946) Luther, 1955 ()

Figure 5. Gieysztoria bellis (Marcus, 1945). A, Dorsal view of a squashed live animal; B (1–4), Penis stylet of a whole-mounted individual in different focal planes with some bent spines and weak distal rings (same scale bar for all photographs); C, Detail of the male reproductive system of a whole-mounted individual; D (1–2), Penis stylet of a whole-mounted individual in different focal planes; E, Schematic representation of the penis stylet in photograph B (1–4); F, Schematic representation of the penis stylet in photograph D (1–2).

Material studied

Five individuals observed alive, studied in whole-mounted preparations (MUSM-INV 4795–4799).

Locality sampled

Chillón River (11°44ʹ1.8”S, 76°58ʹ19.56”W; 11°44ʹ4.38”S, 76°58ʹ20.52”W; 11°43ʹ57”S, 76°58ʹ17.58”W) in temporary ponds, near Trapiche, Canta Province, Lima region (2015/10/31) (temperature: 25.4 °C; pH: 9.16).

Distribution

Tietê River, city of São Paulo, Brazil [Citation14].

Description and remarks

Live mature animals are 300–700 µm long and 67–162.2 µm wide. Reddish-brown pigmentation present throughout the body (). In the male reproductive system, the thick-walled seminal vesicle is 28.5–36.1 µm long and 31.2–37.1 µm wide and is completely filled with spermatozoa (). The seminal vesicle is partly separated from the prostatic vesicle by a septum (). The “U”-shaped prostatic vesicle is 20.6–21.8 µm long and 26.7–27.3 µm wide, with granular prostatic glands (). The 37–45.1 µm-long crown-like penis stylet has a smooth girdle, 2.7–8 μm high. In some stylets, the girdle has two weak distal rings (). The girdle has 20–21 fang-like spines of similar size and shape. Spines are 31.2–38.9 µm long and 2.5–3.7 µm wide, directed slightly outwards (). The egg is 60.9 µm long and 37.3 µm wide. A pair of dark green vitellaria with finger-like projections run from the posterior end of the pharynx to the end of the intestine (). The body length and the number of spines of the penis stylet of individuals from Peru are within the species range, with some differences regarding specimens from Brazil. Peruvian individuals have a shorter and smooth non-fenestrated girdle, not reported by Marcus [Citation14]. In addition, Marcus [Citation14] described ~12 bridges between the girdle and the 19 spines of the stylet, and the spines were not projections of the bridges. In this sense, individuals from Peru have no bridges between the girdle and the 20–21 spines, but two weak rings were present in some individuals. Also, individuals from Peru have larger fang-like spines, while Marcus [Citation14] reported shorter and slender spines with cone-like distal tips. The girdle, could be a variable structure within species of Gieysztoria since observations in other species suggest a remarkable variation in the height of the girdle during maturity [Citation50]. Weak distal rings observed in Peruvian individuals could suggest that the girdle presents intraspecific differences. Morphological variations of the penis stylet within species populations are usual within Gieysztoria [Citation47,Citation49], but the number and size of spines are usually stable [Citation50]. This is the first record of G. bellis in Peru and the second for the Neotropical region.

Prorhynchida Laumer and Giribet, 2014

Prorhynchidae Hallez, 1894

Prorhynchus Schultze, 1851

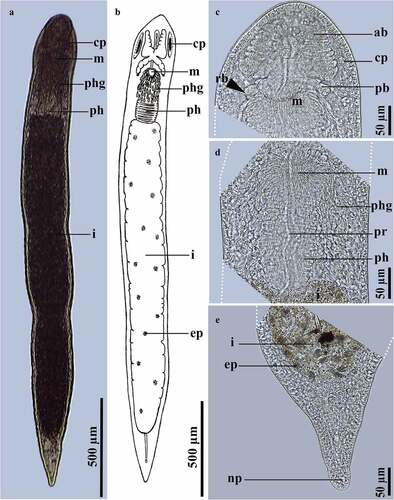

Prorhynchus stagnalis Schultze, 1851 ()

Figure 6. Prorhynchus stagnalis Schultze, 1851. A, Dorsal view of the habitus; B, Detail of the anterior end of the body in sequence of movements (no scale bar available). Geocentrophora applanata (Kennel, 1888). C, Dorsal view of the habitus, sequence of movement; D, Detail of the anterior region of the body; E, Schematic representation of the habitus.

Material studied

A single individual observed alive, studied on a whole-mounted preparation.

Locality sampled

Chillón River (11°43ʹ30.9”S, 76°57ʹ54.1”W) in temporary pond, near the river in Trapiche, Canta Province, Lima region (2015/7/23) (temperature: 26 °C; pH: 8.3).

Other localities in Peru

Loreto Region [Citation34].

Distribution

Widely distributed [Citation51].

Description and remarks

Live mature individual ~3200 µm long and slender (). The hollow spine of the male reproductive system is ~77.2 µm long, and concentric bars are ~33 µm long. The female reproductive system is at the middle of the body and is composed of a germovitellarium. The hollow spine of the penis stylet and the concentric bars of the individual studied from Peru are within the species range (50–123 µm and ~51 µm, respectively) [Citation6,Citation11,Citation26,Citation52,Citation53]. These findings extend the distribution of this species to the central coast of Peru.

Geocentrophora de Man, 1876

Geocentrophora applanata (Kennel, 1888) ()

Material studied

A single individual observed alive, studied on a whole-mounted preparation.

Locality sampled

Chillón River (11°43ʹ30.9”S, 76°57ʹ54.1”W) in temporary pond, near the river in Trapiche, Canta Province, Lima region (2015/7/23) (temperature: 22.1 °C; pH: 8.2).

Other localities in Peru

Loreto Region [Citation34].

Distribution

Widely distributed [Citation51].

Description and remarks

Live mature, whitish-colored individual, ~2230 µm long and flattened. The anterior end is flabelliform, while the posterior end is rounded. Two brownish eyes at both sides of the pharynx. Features observed in the single individual from Peru agree with descriptions of Geocentrophora applanata [Citation6,Citation11,Citation31,Citation53]. This is the first record in Lima, on the central coast of Peru.

Discussion

Peru presents great invertebrate diversity [Citation54–57], but microscopic aquatic invertebrates such as microturbellarians are not usually considered in assessments and inventories of biodiversity [Citation5,Citation30]. In the last two decades, sporadic investigations on microturbellarians were mainly performed in the rainforest region of this country [Citation5,Citation22,Citation24,Citation29,Citation30,Citation34]. These investigations demonstrated the potential high diversity of microturbellarians with the description of six new species [Citation22,Citation24,Citation29]. However, a vast territory in which these organisms are very likely to occur remains unexplored. In this sense, the central coastal region of Peru has rivers, such as the Chillón River, which has the following features: it is a few km long, with altitudinal gradient and with notorious seasonal water level fluctuations [Citation32]. These features create heterogeneous environments in which microturbellarians can be expected to inhabit. Nevertheless, there are only three records of microturbellarians (Macrostomum quiritium Beklemischev, 1951; M. tuba Graff, 1882 and Yagua lutheri du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1958) living in these rivers [Citation5,Citation28].

Stenostomum is a rich and widely distributed genus [Citation3,Citation24], but species identification can be difficult to discern. Diagnostic features need to be examined in live individuals [Citation43]. The species of Stenostomum reported here show most of the diagnostic features mentioned in their original descriptions and posterior reviews [Citation14,Citation21,Citation36,Citation37]. Individuals of Myostenostomum from Peru present a muscular belt, in addition to features on the anterior and posterior brain lobes that correspond to descriptions for M. vanderlandi [Citation26,Citation46,Citation58].

The species of Gieysztoria from Peru are only represented by the Inaequales group, that is, species with spines of different shapes and stylet sizes (G. complicata (Fuhrmann, 1914), G. chiqchi Damborenea, Brusa & Noreña, 2005, G. kasasapa Damborenea, Brusa & Noreña, 2005, G. sasa Damborenea, Brusa & Noreña, 2005) [Citation22]. Thus, the two new records (G. cuspidata and G. bellis) represent the first record of an Aequales group species (specimens with spines of similar shape and stylet sizes) in Peru. In addition, evidence suggests that the morphological complexity of the penis stylet in the species of Gieysztoria is greater in South America [Citation17,Citation20,Citation22,Citation59]. However, consolidated information on species diversity, distribution and dispersal patterns makes it difficult to observe clearer traits in the penis stylet configuration among biogeographical regions [Citation60]. The finding of G. cuspidata in the Neotropical region provides greater support to the hypothesis that certain groups of species (e.g. cuspidata-isoldeae) could represent an ancient lineage, with G. cuspidata already well established in the Mesozoic [Citation60].

The species of Prorhynchidae found in Peru are well-known and are found worldwide [Citation6,Citation11,Citation34,Citation51–53]. Unfortunately, few individuals of P. stagnalis were collected. These animals are known to be fragile when studied alive and are also sensitive to temperature variations [Citation61] thereby preventing further information gathering.

Microturbellarians play important roles in continental aquatic environments. For instance, experiments have demonstrated that species of Stenostomum prey on cladocerans and rotifers and can affect population densities and structured microinvertebrate communities [Citation62,[Citation63]]. Similarly, species of Gieysztoria prey on microinvertebrates as well as individuals of the same species [Citation64]. Therefore, understanding the population dynamics of microturbellarian species in freshwater ecosystems is necessary to obtain better understanding of the trophic chains in Peruvian microinvertebrates.

In conclusion, the diversity of microturbellarians in Peru is far from being properly cataloged, with only 31 species having been recorded to date. More data is needed to provide a better panorama of the freshwater invertebrate communities and to obtain clearer evidence to assess species richness in continental waters, such as those in rivers of the Pacific slope in Peru. The results of the present study increase the number of microturbellarian species in Peru to 36 species, five of which were recorded for the first time. Likewise, one species (G. cuspidata) is recorded for the first time in the Neotropical region, providing evidence to establish a biogeographical hypothesis of distribution from geological eras.

Acknowledgments

We kindly thank Roberto Huanaco and Isabel Centeno for their help in field work, and Karen Velasquez for the map design. We thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and observations. The authors are grateful to Donna Pringle for reviewing the language and style of the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Schockaert ER, Hooge M, Sluys R, et al. Global diversity of free-living flatworms (Platyhelminthes, ‘Turbellaria’) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia. 2008;595(1):41–48.

- Noreña C, Damborenea C, Brusa F. Platyhelminthes de vida libre – microturbellaria – dulceacuícolas en Argentina. Insugeo. 2004;12(1):225–238.

- Noreña C, Damborenea C, and Brusa F. Phylum Platyhelminthes. In: Thorp J, and Rogers D, editors. Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates. 4th (London: Elsevier/Academic Press). 2015. p. 181–203.

- Van Steenkiste N, Volonterio O, Schockaert E, et al. Marine rhabdocoela (Platyhelminthes, Rhabditophora) from Uruguay, with the description of eight new species and two new genera. Zootaxa. 2008;1914(3):1–33.

- Reyes J, and Brusa F. Species of Macrostomum (Macrostomorpha: Macrostomidae) from the coastal region of Lima, Peru, with comments on M.rostratum Papi, 1951. Zootaxa. 2017;4362(2):246–258.

- Young JO. Keys to the freshwater microturbellarians of Britain and Ireland: with notes on the their ecology. 1st ed. England: Freshwater Biological Association; 2001.

- Van Steenkiste N, Davison P, and Artois T. Bryoplana xerophila n. g. n. sp., a new limnoterrestrial microturbellarian (Platyhelminthes, Typhloplanidae, Protoplanellinae) from epilithic mosses, with notes on its ecology. Zoolog Sci. 2010;27(3):285–291.

- Braccini JAL, Amaral SV, Leal-Zanchet AM. Microturbellarians (Platyhelminthes and Acoelomorpha) in Brazil: invisible organisms? Brazilian J Biol. 2016;76(2):476–494.

- Braccini JAL, Brusa F, Leal-Zanchet AM. Six freshwater microturbellarian species (Platyhelminthes) in permanent wetlands of the coastal plain of southern Brazil: new records, abundance, and distribution. Check List. 2017;13(6):849–855.

- Marcus E, and Turbelário O. Mesostoma ehrenbergii (Focke 1836) no Brasil. Bol Ind Anim. 1943;6:12–15.

- Marcus E. Sobre duas Prorhynchidae (Turbellaria), novas para o Brasil. Arq Do Mus Parana. 1944;4:3–46.

- Marcus E. Sôbre Catenulida Brasileiros. Boletins da Fac Filos Ciencias e Let da Univ Sao Paulo Zool. 1945;10:3–133.

- Marcus E. Sobre microturbellarios do Brasil. Comun Zool Del Mus Hist Nat Montevideo. 1945;1:1–60.

- Marcus E. Sobre Tubellaria Brasileiros. Boletins da Fac Filos Ciencias e Let da Univ Sao Paulo Zool. 1946;11:5–254.

- Marcus E. Turbellaria do Brasil. Boletins da Fac Filos Ciencias e Let da Univ Sao Paulo Zool. 1948;13:11–243.

- Marcus E. Turbellaria Brasileiros. Boletins da Fac Filos Ciencias e Let da Univ Sao Paulo Zool. 1949;14:7–156.

- Brusa F, Damborenea MC, and Norena C. A new species of Gieysztoria (Platyhelminthes, Rhabdocoela) from Argentina and a kinship analysis of South American species of the genus. Zool Scr. 2003;32(5):449–457.

- Brusa F, Damborenea C, and Noreña C. ‘Dalyellioida’ (Platyhelminthes, Rhabdocoela) from the Río de la Plata estuary in Argentina, with the description of two new species of Gieysztoria. Zootaxa. 2008;1861(1):1–16.

- Brusa F. Macrostomida (Platyhelminthes: Rhabditophora) from Argentina, with descriptions of two new species of Macrostomum and of stylet ultrastructure. Zoolog Sci. 2006;23(10):853–862.

- Noreña C, Brusa F, Faubel A. Census of ‘Microturbellarians’ (free-living Platyhelminthes) of the zoogeographical regions originating from Gondwana. Zootaxa. 2003;146(1):1–34.

- Noreña C, Brusa F, and Damborenea C. A taxonomic revision of South American species of the genus Stenostomum O. Schmidt (Platyhelminthes: catenulida) based on morphological characters. Zool J Linn Soc. 2005;144(1):37–58.

- Damborenea C, Brusa F, and Noreña C. New species of Gieysztoria (Platyhelminthes, Rhabdocoela) from Peruvian Amazon floodplain with description of their stylet ultrastructure. Zoolog Sci. 2005;22(12):1319–1329.

- Damborenea C, Brusa F, Noreña C. New Dalyelliidae (Platyhelminthes, Rhabditophora) from Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, and Their stylet ultrastructure. Zoolog Sci. 2007;24(8):803–810.

- Damborenea C, Brusa F, and Almagro I, et al. A phylogenetic analysis of Stenostomum and its neotropical congeners, with a description of a new species from the Peruvian Amazon Basin. Invertebr Syst. 2011;25(2):155–169.

- Adami M, Damborenea C, and Ronderos JR. A new limnic species of Macrostomum (Platyhelminthes: macrostomida) from Argentina and its muscle arrangement labeled with phalloidin. Zool Anzeiger. 2012;251(3):197–205.

- Reyes J, Binow D, Vianna RT, et al. Free-living microturbellarians (Platyhelminthes) from wetlands in southern Brazil, with the Description of three new species. Zool Stud. 2021;60(22):1–33.

- Beauchamp P. Percy sladen trust expedition to Lake Titicaca in 1937. V. Rotifers et Turbellaries. Third series. Trans Linn Soc London. 1939;1:51–79.

- du Bois-reymond Marcus E. On South American Turbellaria. An Acad Bras Cienc. 1958;30(3):391–417.

- Noreña C, Damborenea C, Escobedo Torres M. Two New Rhabdocoels (Platyhelminthes) from the Peruvian Amazon floodplain. Biodivers Conserv. 2006;15(5):1609–1620.

- Reyes J, Severino R, and Vargas M, et al. First report of Catenula lemnae Duges, 1832 (Platyhelminthes: catenula: catenulidae) in the high-altitude lake Junin from the Junin Region – Peru. Neotrop Helminthol. 2017;11(2):519–523.

- Brusa F, Leal-Zanchet AM, and Noreña C, et al. Phylum Platyhelminthes. In: Damborenea C, Rogers DC, and Thorp JH, editors. Thorp and Covich’s freshwater invertebrates: keys to neotropical and Antarctic Fauna. 4 th ed. Vol. 1; 2020. p. 101–120. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press.

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Perú. Estudio Linea Base Ambiental de la Cuenca del Río Chillón. Proyecto de la Línea Base de Cuenca de Ríos. Servicio de Consultoria para la Elaboracion de Linea Base de Cuencas de Ríos. Lima: Perú; 2021. p. 1–280.

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):671–675.

- Noreña C, Damborenea C, Brusa F, et al. Free-living Platyhelminthes of the Pacaya-Samiria national reserve, a Peruvian Amazon floodplain. Zootaxa. 2006;1313(1):39–55.

- von Graff L. Acoela, Rhabdocoela und Alloeocoela des Ostens der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika. Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Zool. 1911;99:321–428.

- Kepner WA, and Carter JS. Ten well-defined new species of Stenostomum. Zool Anz. 1931;93:108–123.

- Nuttycombe JW, and Waters AJ. The American species of the Genus Stenostomum. Proc Am Philos Soc. 1938;79(2):213–301.

- Nasonov NV. Les trats généraux de la distribution géographiquedes Turbellaria rhabdocoelida dans la Russie, etc. Bull l’Académie Des Sci Russ. 1924;1924:27–352.

- Kolasa J. Turbellaria and Nemertini. Bottom fauna of the heated Konin lakes. Monogr Fauny Pol. 1977;7:27–46.

- Nasonov NV. Sur la faune des Turbellaria de la peninsule de Kola aux environs de Kandalaksa (In Russian). Bull l’Académie Des Sci Russ. 1923;1923:2–3.

- van der Land J. Kleine dieren uit het zoete water van Suriname verslag van een onderzoek in 1967. Zool Bijdr. 1970;12:3–46.

- Kolasa J. Turbellaria and Nemertini of greenhouses in Poznan. Acta Hydrobiol Krakow. 1973;15(2):227–245.

- Larsson K, Willems W. Report on freshwater Catenulida (platyhelminthes) from Sweden with the description of four new species. Zootaxa. 2010;18(2396):1–18.

- Luther A. Die Turbellarien Ostfennoskandiens. I. Acoela, Catenulida, Macrostomida, Lecithoepitheliata, Prolecithophora, und Proseriata. Acta Soc pro Fauna Flora Fenn. 1960;7:1–155.

- Lanfranchi A, Papi F. Turbellaria (excl. Tricladida). In: Illies J, editor. Limnofauna Europaea. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Gustav Gustav Fischer Verlag/Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger B.V; 1978. p. 5–15.

- Tokinova RP, and Berdnik SV. Report on two rare Myostenostomum species (Platyhelminthes: catenulida) from the Volga River Basin. Zoosystematica Ross. 2017;26(2):199–204.

- Van Steenkiste N, Tessens B, Krznaric K, et al. Dalytyphloplanida (Platyhelminthes: Rhabdocoela) from Andalusia, Spain, with the description of four new species. Zootaxa. 2011;2791(1):1–29.

- Noreña C, Eitam A, Blaustein L. ‘Microturbellarian’ flatworms (Platyhelminthes) from freshwater pools: new species and records from Israel. Zootaxa. 2008;1705(1):1–20.

- Van Steenkiste N, Gobert S, Davison P, et al. Freshwater Dalyelliidae from the Nearctic (platyhelminthes, rhabdocoela): new taxa and records from Ontario, Canada and Michigan and Alabama, USA. Zootaxa. 2011;32(3091):1–32.

- Lu Y-H, Wu -C-C, Xia X-J, et al. Two new species of Gieysztoria (Platyhelminthes, Rhabdocoela, Dalyelliidae) from a freshwater artificial Lake in Shenzhen, China. Zootaxa. 2013;3745(5):569–578.

- Tyler S, Schilling S, Hooge M, et al. Turbellarian taxonomic database. Version 1.7. [ Online]. [Cited 2021 Mar 25].http://turbellaria.umaine.edu/turbella.php

- Tyler S, Varjabedian A, and Hamami E. Functional morphology of the venom apparatus of Prorhynchus stagnalis (Platyhelminthes, Lecithoepitheliata). Zoomorphology. 2018;137(1):19–29.

- Steinböck O. Monografie der Prorhynchidae (Turbellaria). Zeits F Morph U Ökol D Tiere. 1927;8(3–4):538–662.

- Lamas G. Comparing the butterfly faunas of Pakitza and Tambopata, Madre De Dios, Peru, or why is Peru such a mega-diverse country? In: Ulrich H, editor. Tropical biodiversity and systematics. 1997. p. 165–168. Germany : Bonn, Zoologisches Forschungsinstitut und Museum Alexander Koenig Actas.

- Ramírez R, Paredes C, Arenas J. Moluscos del Perú. Rev Biol Trop. 2003;51(Suppl. 3):225–284.

- Silva D. Species composition and community structure of Peruvian rainforest spiders: a case study from a seasonally inundated forest along the Samiria river. Rev Suisse Zool. 1996 1 ;597–610.

- Chaboo CS. Beetles (Coleoptera) of Peru: a survey of the families. Part I. Overview. J Kansas Entomol Soc. 2015;88(2):135–139.

- Rogozin AG. A short revision of Myostenostomum (Turbellaria, Catenulida). Zool Zhurnal. 1992;71(10):5–11.

- Artois T, Willems W, De Roeck E, et al. Freshwater Rhabdocoela (Platyhelminthes) from Ephemeral Rock Pools from Botswana, with the description of four new species and one new genus. Zoolog Sci. 2004;21(10):1063–1072.

- Van Steenkiste N, Tessens B, and Willems W, et al. The ‘Falcatae’, a new Gondwanan species group of Gieysztoria (Platyhelminthes: dalyelliidae), with the description of five new species. Zool Anzeiger. 2012;251(4):344–356.

- Percival E. The Genus Prorhynchus in New Zealand. (Phylum Platyhelminthes, Class Turbellaria). Trans R Soc New Zealand. 1945;75(1):33–41.

- Nandini S, Sarma SSS, and Dumont HD. Predatory and toxic effects of the turbellarian (Stenostomum cf leucops) on the population dynamics of Euchlanis dilatata, Plationus patulus (Rotifera) and Moina macrocopa (Cladocera). Hydrobiologia. 2011;662(1):171–177.

- Núñez-Ortiz AR, Nandini S, and Nandini SSS. Demography and feeding behavior of Stenostomum leucops (Dugés, 1828). J Limnol. 2016;75(s1):48–55.

- Nandini S, and Sarma SSS. Demographic characteristics of cladocerans subject to predation by the flatworm Stenostomum leucops. Hydrobiologia. 2013;715(1):159–168.