Abstract

We describe the occurrence of a papillary squamous infrasellar craniopharyngioma isolated to the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus in a 48-year-old male presenting with epistaxis and nasal obstruction. Diagnosis was made by histological analysis of incisional biopsy in clinic. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging were performed to evaluate the extent of tumor involvement. The tumor was excised by endoscopic surgery in the operating room with intraoperative frozen section analysis to confirm clear margins. The patient had an uncomplicated post-operative course and no evidence of tumor recurrence at eight months follow-up. This represents the third confirmed case of infrasellar craniopharyngioma isolated to the nasal cavity.

Introduction

Craniopharyngioma is a benign, epithelial neoplasm that accounts for 1.5–3% of all intracranial tumors,[Citation1,Citation2] most commonly arising from the sella turcica. Craniopharyngiomas with an infrasellar component are extremely rare, with ∼50 cases reported to date in the literature.[Citation3] Among these, 35 cases of infrasellar craniopharyngioma also had suprasellar involvement. The remaining 15 cases of infrasellar craniopharyngioma were extracranial with no suprasellar component. Among these purely infrasellar craniopharyngiomas, three did not contact the skull base and were isolated to the nasal cavity with involvement of the maxillary sinus.[Citation1,Citation4]

Clinical presentation of craniopharyngioma is dictated by the localization and size of the tumor. Supra- and intrasellar craniopharyngiomas typically present with visual or endocrine disorders (such as diplopia or diabetes insipidus), whereas infrasellar craniopharyngiomas may present with epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and frontal headache.[Citation1,Citation5,Citation6] We present here, a case of a unifocal infrasellar craniopharyngioma confined to the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus without evidence of intracranial involvement or contact with the skull base.

Case report

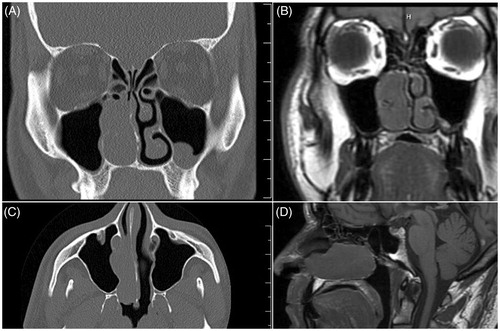

A 48-year-old diabetic man was presented with right-sided nasal congestion. He reported a two-year history of untreated, intermittent nose bleeds with occasions of ‘blown tissue’ out of his nose, often followed by up to 20 h of epistaxis. In-clinic, rigid nasal endoscopy showed a polypoid mass in the right nasal cavity extending from superior to the middle turbinate to the nasal floor. The left nasal cavity showed a deviated septum with no masses, polyps, or purulent discharge. An incisional biopsy performed in clinic indicated that the mass was histologically suggestive of craniopharyngioma. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a right sided nasal mass extending into the maxillary sinus near the nasolacrimal duct (Figure ). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was consistent with CT findings and showed no intracranial lesions or contact with the skull base (Figure ).

Figure 1. Imaging confirms infrasellar craniopharyngioma isolated to the nasal cavity. (A) Coronal CT showing a right-sided nasal mass extending into the maxillary sinus with proximity to the nasolacrimal duct. (B) Coronal MRI showing a right-sided nasal mass extending into the maxillary sinus with proximity to the nasolacrimal duct with no intracranial extension of the mass. (C) Axial CT showing mass in the right nasal cavity extending into the maxillary sinus without evidence of intracranial involvement or contact with the skull base. (D) Sagittal MRI showing a mass in the right nasal cavity with no contact with the skull base. (Ruler markings indicate 1cm segments).

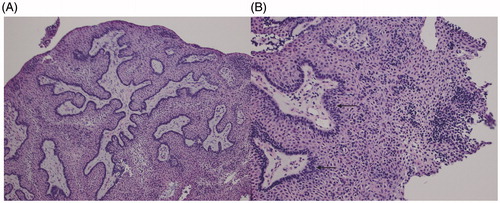

Transnasal endoscopic surgical approach for resection of the tumor revealed a large, friable, exophytic mass encompassing the middle portion of the right inferior turbinate. Biopsies were obtained from the anterior, middle, and posterior aspects of the inferior turbinate. Frozen section analysis showed the middle segment to be positive for neoplastic tissue. A medial maxillectomy was performed, removing the uncinated process and the inferior turbinate remnant to the nasal floor. All final margins were free of disease including the descending palatine artery region and the medial wall of the maxillary sinus. The final pathologic diagnosis was craniopharyngioma, WHO grade 1. The tumor was largely papillary in architecture, but was noted to be present adjacent to turbinate bone. The bulk of the tumor was squamoid, and the subtype of craniopharyngioma was papillary (Figure ).

Figure 2. Histopathological imaging confirms a papillary squamous craniopharyngioma. (A) Low power (25×) microscopy image depicting the tumor’s largely papillary architecture and solid appearance. Calcifications and wet keratinization were noted to be absent. (B) Higher power (50×) image of the papillary squamous craniopharyngioma (WHO Grade I) depicting squamoid cells and tall, dark palisading nuclei (black arrows). The tumor is solid in appearance and does not show calcifications.

Follow-up rigid nasal endoscopy in clinic on post-operative day 10 was unremarkable with the exception of crusting at the site of the medial maxillectomy. Aside from continued crusting and one episode of maxillary sinusitis successfully treated with antibiotics, the patient underwent an uncomplicated recovery with no evidence of recurrent craniopharyngioma at eight months follow-up.

Discussion

Craniopharyngiomas are rare, benign neoplasms that are thought to originate from remnants of the obliterated craniopharyngeal canal, which traces the migration of Rathke’s pouch as it ascends and differentiates into the adenohypophysis. They are typically observed within the sella turcica, though rare infrasellar cases have been reported. Isolated infrasellar cases without intracranial involvement are even rarer. This case represents an unusual presentation of craniopharyngioma because of its infrasellar confinement within the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus with no contact with the skull base. To date, including the current case, only three such cases have been reported.[Citation1,Citation4]

Two main histologic types have been described: adamantinomatous and papillary squamous. Cases of adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma more commonly present in childhood and are characterized by an inner variable pattern of anastomosing trabeculae, cords, and cysts surrounded by rim of cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells.[Citation1] Calcification is usually present in 90% of tumors in the adamantinomatous subtype.[Citation7] Cases of papillary squamous craniopharyngioma, as observed in our case, generally occur in adults and are characterized by a more solid appearance with squamous epithelial cords and papillae separated by loose stroma. Calcifications are uncommon in the papillary squamous subtype, and prognosis is generally better compared to adamantinomatous tumors.[Citation8,Citation9]

Although usual suprasellar craniopharyngioma is not considered to be a malignant neoplasm,[Citation1] aggressive and complete surgical excision is recommended. Recurrence rates are reported to be up to 50% with incomplete tumor excision.[Citation10] The five-year survival rate for all treated suprasellar craniopharyngiomas is ∼80%.[Citation2,Citation11] The use of adjuvant radiotherapy has been shown to improve survival in cases of incomplete excision,[Citation12] but successful first-time complete resection is associated with lower mortality than incomplete resection without adjuvant therapy.[Citation13] In the presented case, we performed a complete tumor excision with negative margins and thus determined no need for adjuvant radiotherapy. Infrasellar craniopharyngiomas have an unclear prognosis given the rarity of the tumor at this site. We hypothesize that isolated infrasellar craniopharyngioma may have a better prognosis than suprasellar craniopharyngiomas due to the lack of intrusion upon brain structures. Long-term follow up, however, is warranted due to the lack of data on recurrence rates for isolated infrasellar craniopharyngiomas.[Citation14] Our patient had no evidence of a recurrent craniopharyngioma at eight months follow-up.

Notes on contributors

Kunjan B. Patel is a medical student at Saint Louis University. He has diverse research interests and is looking forward to contribute to the medical literature in Otolaryngology.

Farhoud Faraji is an MD/PhD medical student at St. Louis University. He has completed his PhD and continues to contribute to the medical literature as he finishes his MD program.

Dr. Nancy Phillips is an associate professor in the Department of Pathology at St. Louis University whose research interests include evaluation of several novel tumor suppressor genes in gynecological cancers.

Dr. Joseph D. Brunworth is a board-certified assistant professor in the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. He specializes in Rhinology & Sinus Surgery, and his research interests include nasal tumors, chronic rhinosinusitis, skull base surgery, hemostasis, quality of life, and outcomes research.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist in relation to the work. The manuscript has not been presented before any professional otolaryngological association.

References

- Byrne MN, Sessions DG. Nasopharyngeal craniopharyngioma. Case report and literature review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:633–639.

- Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:547–551.

- Hwang KR, Lee JY, Byun JY, et al. Infrasellar craniopharyngioma originating from the pterygopalatine fossa with invasion to the maxillary sinus. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:422–424.

- Ahsan F, Rashid H, Chapman A, et al. Infrasellar craniopharyngioma presenting as epistaxis, excised via Denker’s medial maxillectomy approach. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:895–898.

- Magill JC, Ferguson MS, Sandison A, et al. Nasal craniopharyngioma: case report and literature review. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:517–519.

- Dunham BP, Javia LR, Bilaniuk LT, et al. Bilateral nasal obstruction due to an intranasal craniopharyngioma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2010;5:57–62.

- Kundu S, Dewan K, Varshney H, et al. An atypical rare case of extracranial craniopharyngioma. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66:122–125.

- Falavigna A, Kraemer JL. Infrasellar craniopharyngioma: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59:424–430.

- Adamson TE, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, et al. Correlation of clinical and pathological features in surgically treated craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:12–17.

- Weiner HL, Wisoff JH, Rosenberg ME, et al. Craniopharyngiomas: a clinicopathological analysis of factors predictive of recurrence and functional outcome. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:1001–1010.

- Rajan B, Ashley S, Gorman C, et al. Craniopharyngioma-a long-term results following limited surgery and radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1993;26:1–10.

- Manaka S, Teramoto A, Takakura K. The efficacy of radiotherapy for craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:648–656.

- Yasargil MG, Curcic M, Kis M, et al. Total removal of craniopharyngiomas. Approaches and long-term results in 144 patients. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:3–11.

- Yu X, Liu R, Wang Y, et al. Infrasellar craniopharyngioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:112–119.