Abstract

Intratympanic membrane cholesteatoma (ITMC) is uncommon. We report a case of ITMC in the right ear of a four-month-old male infant. The lesion was incidentally discovered during a routine ear examination when the boy was admitted for bacterial meningitis. The majority of previously reported cases of ITMC were seen in ears with a history of surgery or trauma, but our patient’s affected ear had experienced neither of these. His ITMC was excised at our clinic under local anaesthesia without any adverse events. We resected the ITMC using a procedure similar to myringotomy. This surgery is simple, minimally invasive, and can be performed in most otolaryngology clinics with commonly available devices. Small white masses found on the surface of the tympanic membrane should be carefully examined for the possibility of ITMC, because untreated ITMCs can grow and destroy the surrounding bone structure, in the same manner as any other acquired cholesteatoma.

Introduction

Intratympanic membrane cholesteatoma (ITMC) is seldom encountered in the clinic. It normally appears as a small white, spherical mass, and it may be overlooked without careful observation of the tympanic membrane. When left untreated, it will gradually grow and destroy the surrounding bony structures such as the ossicles, inner ear, fallopian canal, and tegmen tympani in the same manner as the more commonly seen cholesteatoma. Herein, we present a case of ITMC in the right ear of a four-month-old infant. It was excised at our clinic under local anaesthesia without any adverse events. No recurrence was seen 17 months after the surgery.

Case report

A four-month-old male infant was admitted to our hospital’s department of paediatrics for bacterial meningitis. The admitting paediatricians, who examined his ears as a routine inspection, noticed a white small lesion in the right tympanic membrane. The infant was referred to the department of otolaryngology for further investigation. The boy had no history of ear surgery or ear trauma. His hearing was evaluated at birth as a screening measure with an unremarkable result.

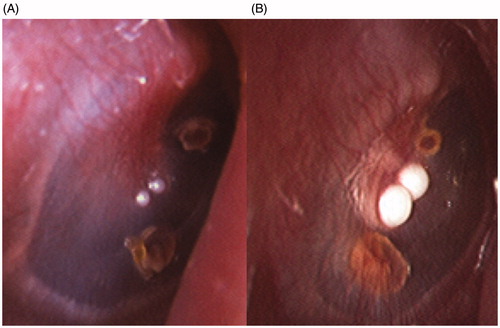

Microscopic observation revealed two small white spherical masses in the lower anterior quadrant of the right tympanic membrane (Figure ). The diameters of the masses were estimated to be less than 1 mm each. Although these lesions appeared to originate from the surface of the tympanic membrane, it was possible that a middle ear mass was protruding through the tympanic membrane. Therefore, a high-resonance computed tomography (CT) scan was performed to exclude the possibility of any related lesion inside the right middle ear. Unfortunately, no useful information was obtained because the area was filled with a low-density substance, which was assumed to be fluid accumulation.

Figure 1. (A) Two masses adjacent to the umbo of the malleus. (B) Both lesions grew and eventually fused together.

His fever was as high as 39.9 °C on admission, and the clinical manifestations were consistent with bacterial meningitis. Treatment with antibiotics and gamma globulin was immediately commenced, and the patient showed marked improvement. Analysis of both the bacterial culture of blood and cerebrospinal fluid samples obtained on admission had shown Haemophilus influenza infection, and he was diagnosed with concomitant sepsis. Though the origin of the infection was not clear, the paediatricians presumed that it had been caused by a preceding upper airway infection because he had had cold-like symptoms, such as a cough, slight fever, and running nose, prior to admission. Otogenic meningitis was not supported as the findings on visual inspection of the tympanic membrane were unremarkable other than the ITMC on the right side and the lack of clinical symptoms of suppurative otitis media, although its possibility was not definitively ruled out. He became afebrile on day 6 of admission as a result of the effective treatment. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study performed on day 10 demonstrated a high signal lesion on diffusion-weighted image (DWI) in the left lateral ventricle, which might possibly be a sign of an abscess. A discreet decision was made to continue the administration of antibiotics instead of discharging. The MRI study was repeated three times until the lesion in the left ventricle had almost disappeared by day 28 of admission. Discharge was once again considered, but on day 30, his body temperature increased to 38.9 °C, accompanied by vomiting and diarrhoea, which proved to be due to a rotavirus infection. The infant recovered from meningitis, sepsis, and rotavirus infection and was discharged without any complications on day 42. We advised that the child be brought in to the otolaryngology department for periodic check-ups of his right ear for the presence of any as-yet undiagnosed lesions.

Four months later, when he was nine months old, the size of the lesions had increased and the masses had fused together (Figure ). This clinical course was consistent with that of ITMC. For the purpose of surgical extirpation and pathological diagnosis, we recommended enucleation of the lesions using an endaural approach. Both the risks and benefits of general and local anaesthesia were explained to the parents. After obtaining their informed consent, the surgery was performed at our clinic under local anaesthesia when the child was 11 months old. He was physically detained for safety purposes following informed consent from the parents by a device called ‘paediatric restrainer’, commercially available from Nikkofines Co. Ltd, Japan. It consists of a firm board and a net to detain the movement of the trunk and extremities of the child. Extreme care was taken not to constrict his neck or the movement of the thorax. A piece of cotton impregnated with topical anaesthetics was applied to the surface of the right tympanic membrane for 10 min. Our topical anaesthetics included 4 mL phenol, 8 mL 4% lidocaine, 4 mL mentha oil, and 20 mL dehydrated ethanol, leading to a total solution of 36 mL. After removal of the cotton, the circumferential epithelium of the fused mass was incised with a myringotome, with special care not to perforate the tympanic membrane. The mass was not adhered to the fibrous layer and was easily removed by blunt dissection. The removal was successful; the fibrous layer of the tympanic membrane remained intact, with no signs of perforation, and the surgery was completed in less than a minute. No adverse events were observed during the procedure. We did not place any dressing over the incised wound.

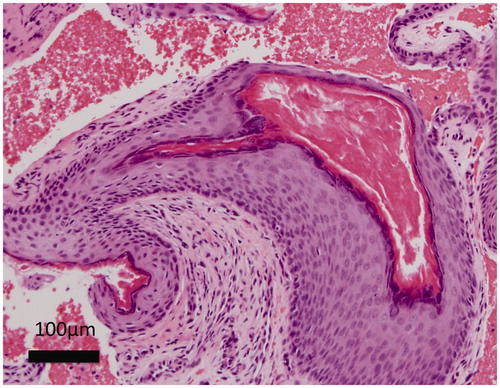

The pathological diagnosis confirmed that the lesion was an ITMC (Figure ). Keratin debris was observed inside a keratinized epithelium sac, which was compatible with cholesteatoma. Judging from the surgical specimen, the ITMC was completely removed.

The patient was followed up periodically at our clinic for 17 months after the procedure. No recurrence of ITMC has been observed during this time.

Discussion

ITMC is not frequently encountered in the clinic, even by otolaryngologists, as it is reportedly very rare.[Citation1] The aetiology of ITMC is not yet known.[Citation2] The majority of reported cases have been seen in ears with a history of ear surgery or ear trauma [Citation3,Citation4] and reports of cases without such a history are very rare.[Citation2,Citation5] Reported ITMCs were mostly discovered incidentally as small white masses adjacent to the umbo.[Citation6] Due to the paucity of cases, an ITMC may be misinterpreted as other manifestations, such as sclerosis of the tympanic membrane.[Citation2,Citation7,Citation8]

If left undiagnosed, the ITMC will gradually grow, and may destroy middle ear structures such as the ossicles, inner ear, tegmen tympani, or fallopian canal.[Citation2,Citation3,Citation5] Therefore, clinicians should be cautious when a small white mass is noticed on the surface of the tympanic membrane. A CT of the ear is usually recommended to exclude a related middle-ear lesion.[Citation5] However, the majority of the ITMC cases are discovered in children less than four years old,[Citation3] who are frequently affected with otitis media. A CT is not always useful because of the possibility of fluid accumulation in the middle ear, as seen in our case. Taking into account both the radiation exposure and the risk of necessary sedation in infants, we do not think that a CT should be a requirement for the diagnosis of ITMC.

Although some reported cases of ITMC resolved spontaneously,[Citation6] ITMCs should be treated by surgical extirpation. However, there is no consensus about the type of removal procedure itself, i.e. general anaesthesia or local anaesthesia, surgery in the office or operating room, choice of surgical instrument, etc. Lee reported nine cases of ITMC resected using a CO2 laser with satisfactory results.[Citation6] This procedure is attractive in that it is minimally invasive. A CO2 laser is not, however, available in every facility.

We removed the ITMC using an endaural approach in a manner very similar to a myringotomy. Instead of penetrating the tympanic membrane, we enucleated the two ITMCs (which were fused as one) using only a myringotome. We used a circumferential incision of the epithelium and then peeled the mass off the fibrous layer. The time required for the resection was less than a minute. This procedure is indicated for ITMCs small enough to allow the visualization of the tympanic membrane, and is not suitable for large ITMCs. If the ITMC is or may be in contact with the ossicles, we do not recommend this method, because in such cases the surgery will be more invasive and there will therefore be a risk of iatrogenic hearing impairment. Simply attempting to squeeze the debris out of the matrix should not be attempted, because complete removal of the matrix is very important, just as with other types of cholesteatoma.

This surgery uses standard devices, including an otological microscope and myringotome, which are usually available in most otolaryngology clinics. It may also be performed in a small facility where general anaesthesia is unavailable. A possible ITMC lesion may be resected using this procedure for biopsy purposes, as long as the lesion is small enough.

In conclusion, any small white mass that has been observed on the surface of the tympanic membrane should be monitored for the possibility of ITMC. Such a lesion should not be left undiagnosed, because if it is indeed ITMC, it will grow and destroy the surrounding bony structures. A small lesion may be enucleated using only local anaesthesia, using a procedure similar to a myringotomy, as in this report. We think a resection by this procedure for diagnostic purposes is justified, as it requires only generally available tools such as a myringotome and is minimally invasive.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Rappaport JM, Browning S, Davis NL. Intratympanic cholesteatoma. J Otolaryngol. 1999;28:357–361.

- Pasanisi E, Bacciu A, Vincenti V, et al. Congenital cholesteatoma of the tympanic membrane. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;61:167–171.

- Reddy CE, Goodyear P, Ghosh S, et al. Intratympanic membrane cholesteatoma: a rare incidental finding. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:1061–1064.

- Nejadkazem M, Totonchi J, Naderpour M, et al. Intratympanic membrane cholesteatoma after tympanoplasty with the underlay technique. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:501–502.

- Yoshida T, Sone M, Mizuno T, et al. Intratympanic membrane congenital cholesteatoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1003–1005.

- Lee CH, Kim JY, Kim YJ, et al. Transcanal CO2 laser-enabled ablation and resection (CLEAR) for intratympanic membrane congenital cholesteatoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:2316–2320.

- Jaisinghani VJ, Paparella MM, Schachern PA. Silent intratympanic membrane cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1185–1189.

- Sakaida H, Takeuchi K. Intratympanic membrane congenital cholesteatoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2015;94:256–260.