Abstract

We describe a case of recurrent hypopharyngeal pyriform sinus fistula after an open neck surgery, which was successfully treated with transoral surgical closure. The patient was a 7-year-old boy who had previously undergone neck surgery for removal of a fistula. The fistula recurred one month later, and transoral closure was selected as a treatment. Under general anesthesia, the fistula was identified in the left pyriform sinus, and cotton balls soaked with trichloroacetic acid were inserted in the fistula opening, after which an electrocautery scalpel was used to close the fistula. At 18 months postoperatively, there has been no recurrence or complications. This is the first report to describe a transoral surgical closure of a recurrent fistula. Transoral surgical closure was successful and resulted in no complications; it thus appears to be an effective treatment option, even for patients who have previously undergone open neck surgery.

Introduction

Hypopharyngeal pyriform sinus fistulae (PSF) are branchiogenic fistulae that open into the pyriform sinus and can cause recurrent abscesses in the anterior neck and acute suppurative thyroiditis.[Citation1] Curative treatment of these fistulae usually entails complete resection of the fistulous tract, but fistula recurrence is not uncommon. Instead, recent reports describe the use of oral endoscopy to successfully reach the fistula opening, which is then closed by cauterization. However, it is uncertain whether this technique is useful for the recurrent cases.[Citation2] We treated the pyriform sinus fistula patient by an open neck surgery, which was then recurred one month after the surgery. Regarding the surgery for the recurrence, open neck surgery would have been difficult due to massive scar tissue formation. This is the first case report that describes the use of oral endoscopy to close a recurrent pyriform sinus fistula after open neck surgery.

Case report

Patient: 7-year-old boy

Principal complaint: Swelling on the left side of the neck

Past history: Unremarkable

History of present illness: The patient had previously developed swelling on the left side of the neck, which was diagnosed as an abscess. Pediatric surgeons treated the abscess by means of open drainage. He later presented to our department for the treatment of suspected infection of a fistula in the hypopharyngeal pyriform sinus. After inflammation had subsided, a contrast radiograph of the hypopharyngeal area of the esophagus was obtained and hypopharyngeal pyriform sinus fistula was diagnosed (Figure ). Three months after his first visit to our department, we attempted radical open neck surgery and complete resection of the fistulous tract. However, inflammation had resulted in considerable scar tissue, and the fistulous tract thus could not be clearly identified. We, therefore, did not attempt to resect the fistula but rather ligated what seemed to the fistulous tract and closed the wound. Recurrence was observed at one month postoperatively, and surgery to open the abscess (Figure ) was performed. We decided that additional open neck surgery was not indicated and instead elected to perform transoral endoscopic fistula closure.

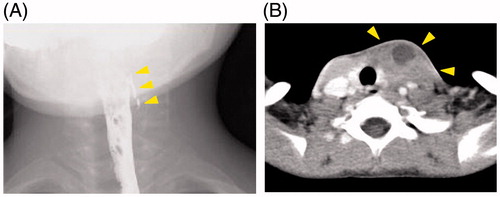

Figure 1. Preoperative images. (A) Contrast radiograph showed a leakage of contrast material on left pyriform sinus. (B) Contrast-enhanced CT after the first open neck surgery showed an abscess of the left anterior neck suspecting recurrence of PSF.

Intraoperative findings

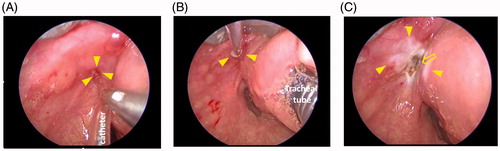

The opening of the fistula could not be identified by endoscopic inspection. Under general anesthesia, a pediatric Weerda laryngoscope, used for procedures requiring distention, was used to inspect the base of the left pyriform sinus. The opening of the fistulous tract could be visualized, and a catheter usually utilized for epidural anesthesia was then used to confirm the presence of the fistulous tract (Figure ). Chemocauterization of the whole length of the fistulous tract was performed by inserting small cotton balls soaked with 30% trichloroacetic acid (Figure ). The mucosa began to whiten after the first treatment. In total, three chemical cauterizations were performed, after which an electrocautery scalpel in coagulation mode was used for cauterization of the internal opening of the fistula (Figure ). In the area of the fistula opening, whitening and transpiration of the mucous membranes was observed, but no healthy mucous membranes near the fistula opening had been cauterized.

Figure 2. Intraoperative microscopy. (A) Catheter was inserted into the opening of the fistula. (B) Whole length of the fistulous tract was chemocauterized. Small white cotton ball soaked with trichloroacetic acid can be seen. (C) Opening of the fistulous tract was electrically cauterized (arrow), Chemocauterized area can be seen as white lesion (arrow heads).

Postoperative follow-up

No obvious complications developed postoperatively. The patient received intravenous supplementation with fluids, as no oral feeding was permitted for two days postoperatively. Oral intake was restarted on day 3 postoperatively. Two months after surgery, contrast radiography of the hypopharyngeal region of the esophagus showed no evidence of fistula (Figure ). At 18 months postoperatively, the patient is free from recurrence.

Discussion

PSF are vestigial remnants of intrauterine fetal formation.[Citation3] Principle of PSF treatment is a surgical resection by an open neck surgery. Recently, less invasive transoral methods without neck skin incision have been proposed, such as direct laryngoscopic exposure of the fistula opening and subsequent chemical or electrical cauterization of the opening.[Citation2–8] However, in all these reports, no recurrent patients after open neck surgery were treated. Moreover, there were no reports on combination of chemical and electrical cauterization. This is the first report to describe a successful treatment of recurrent PSF after an open neck surgery by transoral chemical and electrical cauterization.

As an option for complete surgical removal of PSF, Cha et al. reported favorable long-term effects of a chemocauterization of an internal opening of the fistula.[Citation4] This prevents bacterial invasion of the fistula and thereby prevents inflammation in the micro-spaces of the fistula and subsequent spread of inflammation to surrounding tissue. Regarding the closure of fistula openings, some authors used trichloroacetic acid or silver nitrate for chemical cauterization, whereas others used electrical coagulation or lasers,[Citation2,Citation4–7] which take advantage of the effect of albuminoid degeneration in tissue to cause scar formation. We used combined therapy, namely, chemocauterization of the whole length of the fistulous tract by trichloroacetic acid followed by electrical cauterization of the fistula opening, because the patient wanted this surgery would be the last one. The results were very encouraging, as combined treatment seemed to result in stronger cauterization. This combined cauterization technique is likely to achieve similar results in other patients, and we look forward to future reports on its use and effectiveness. Moreover, there were no severe adverse effects such as recurrent nerve palsy and rupture of the esophagus. Previous papers on transoral surgery for PSF also did not report such complications.[Citation4]

In general, chronic or repeated inflammation due to PFS or preceding open neck surgery can result in scar tissue formation and/or adhesion of the tract to adjacent tissue, which greatly complicates identification and ablation of the tract from surrounding tissue.[Citation4] This was true for the first open neck surgery for our patient. Therefore, we chose the transoral approach in the second surgery, which resulted in a favorable outcome. However, if just a cauterization of the fistula but not a complete removal of fistula is sufficient to prevent the inflammation of PSF, this procedure may be replaced to the open neck surgery. Future studies on long-term effects of transoral chemical and electrical cauterization of PSF as a first line procedure should be investigated.

Severe postoperative complications such as recurrent nerve paralysis did not occur.

Conclusions

Our findings on recurrent PSF after open neck surgery indicate that transoral surgical closure has a curative effect equivalent to more invasive surgical removal of the fistulous tract. Because complications are rare with transoral closure, it may be a better choice as the first-line treatment and may thus replace the open neck surgery.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Takai SI, Miyauchi A, Matsuzuka F, et al. Internal fistula as a route of infection in acute suppurative thyroiditis. Lancet. 1979;1:751–752.

- Jordan JA, Graves JE, Manning SC, et al. Endoscopic cauterization for treatment of fourth branchial cleft sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:1021–1024.

- Miyauchi A, Matsuzuka F, Kuma K, et al. Piriform sinus fistula: an underlying abnormality common in patients with acute suppurative thyroiditis. World J Surg. 1990;14:400–405.

- Cha W, Cho SW, Hah JH, et al. Chemocauterization of the internal opening with trichloroacetic acid as first-line treatment for pyriform sinus fistula. Head Neck. 2013;35:431–435.

- Kim KH, Sung MW, Koh TY, et al. Pyriform sinus fistula: management with chemocauterization of the internal opening. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:452–456.

- Sayadi SJ, Gassab I, Dellai M, et al. Laser coagulation in the endoscopic management of fourth branchial pouch sinus. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2006;123:138–142.

- Pereira KD, Smith SL. Endoscopic chemical cautery of piriform sinus tracts: a safe new technique. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:185–188.

- Miyauchi A, Inoue H, Tomoda C, et al. Evaluation of chemocauterization treatment for obliteration of pyriform sinus fistula as a route of infection causing acute suppurative thyroiditis. Thyroid. 2009;19:789–793.