Abstract

The most frequent cause of unilateral congenital facial paralysis is birth injury, and this injury recovers completely within several weeks. On the other hand, congenital facial paralysis due to facial nerve aplasia is irreversible. After a normal pregnancy and a smooth cesarean section, a 2-month-old girl presented with left facial paralysis. Grading of her facial paralysis was House–Brackmann Grade V and Sunnybrook Grading Score 9. She was diagnosed with complete congenital unilateral facial paralysis. The facial nerve aplasia diagnosis was observed with magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography. Three-dimensional constructive interference in steady state magnetic resonance imaging and high-resolution computed tomography scanning are very useful for diagnosing congenital facial paralysis due to anatomic anomalies. Facial nerve aplasia has been considered a very rare condition, but it is likely a more frequent diagnosis in cases with irreversible congenital facial paralysis.

Introduction

The incidence of congenital facial paralysis is around 0.8–2.3/1000 live births. Congenital unilateral facial paralysis is generally considered to be the result of either developmental or traumatic etiology, and the most frequent cause of unilateral congenital facial paralysis is birth injury. It is estimated that 78–91% of congenital facial paralyses are related to birth injury, and 89–94% of traumatic congenital facial paralysis (birth injury) cases recover completely within several weeks.[Citation1–4] In contrast, congenital unilateral facial nerve paralysis not due to birth injury is irreversible.[Citation5,Citation6] This group of congenital facial nerve paralysis is considered to be the result of a developmental or genetic anomaly of the facial nerve or facial motor nucleus. Although ∼7% of congenital facial paralysis cases have delayed or irreversible facial paralysis, congenital facial nerve aplasia has been considered to be a very rare disease. This case report details a patient with congenital unilateral facial nerve aplasia diagnosed with three-dimensional constructive interference in steady state (3D-CISS) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and high-resolution (HR) computed tomography (CT) scanning.

Case report

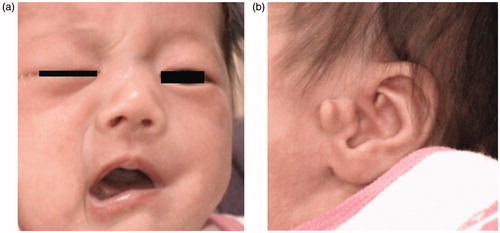

A 2-month-old girl presented with left facial paralysis, which was noted immediately at birth. The girl was delivered by a smooth cesarean section at a gestational age of 37 weeks after a normal pregnancy. Her mother received cesarean surgery because of cephalopelvic disproportion. The Apgar score was unremarkable, and the birth weight was 2654 g. There was no family history of major hereditary diseases. Left total facial paralysis was noticed immediately after birth in her crying face (Figure ). Grading of her facial paralysis was House–Brackmann Grade V and Sunnybrook Grading Score 9. She underwent a newborn hearing screening test and passed on both sides. She was completely healthy except for the left facial paralysis. She was referred to a University hospital for further analysis at the age of 2 months due to the fact that her left facial paralysis persisted. She had a small anomaly of pretragal duplication (Figure ), but examination of both external ear canals and tympanic membranes demonstrated normal development. She had also been diagnosed with bilateral otitis media with effusion (OME) at the age of 2 months, an age when children are especially susceptible to OME. As she was born by cesarean section and the facial paralysis had still not reversed two months after birth, she was suspected to have a congenital developmental disorder of the facial nerve. However, she did not have any problem with breastfeeding, so she was put on watchful waiting.

Figure 1. (a) Left facial paralysis becomes evident when the patient cries. She is not able to close the left eyelid and shows complete unilateral facial palsy on the left side. (House–Brackmann Grade V and Sunnybrook Grading Score 9). (b) There is a small anomaly of pretragal duplication on her left ear.

After 18 months of birth, motor and mental development was normal. She could walk without any balance problems. There were no abnormal neurological findings except for the left complete facial paralysis. Her face was normal looking and symmetrical when she was not crying or smiling. Physical examination of the tympanic membranes demonstrated right-sided OME and no evidence of tumors in the left ear within the tympanic cavity. The right-side OME resolved spontaneously after a few months. She underwent MRI and CT examinations to diagnose her facial nerve condition.

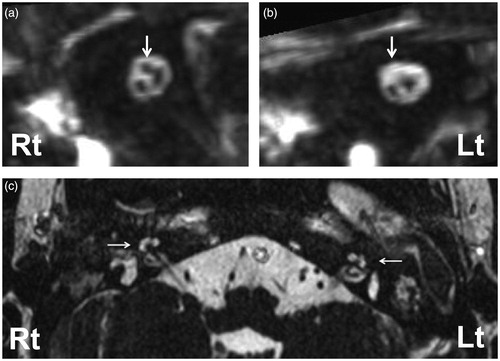

Conventional T1 and T2-weighted MRI images showed no brain abnormalities. There were no significant lateral differences in the facial nucleus. The oblique sagittal MPR was composed from 3D-CISS MRI (heavily T2-weighted images) (Figure ). It demonstrated hypoplasia of the left facial nerve. The right facial nerve was seen in the internal auditory canal (IAC) (Figure , arrow), but the facial nerve was almost absent in the left IAC (Figure , arrow). Bilateral hypoplasia of the semicircular canals was observed, but both sides showed normal cochlear shapes (Figure , arrows).

Figure 2. Oblique sagittal MPR, composed from 3D-CISS MRI (heavily T2 weighted images) of internal auditory canal (IAC) (a: right, b: left) demonstrates hypoplasia of the left facial nerve (b arrow) compared to the right side. The right facial nerve is obvious in the IAC (a arrow) but the left facial nerve is almost absent (b arrow). The cochleae of both sides are normally shaped.

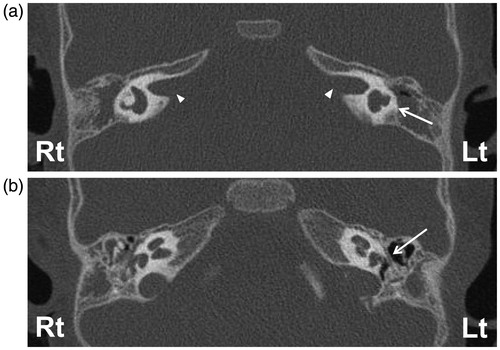

HRCT scanning demonstrated bilateral hypoplasia of the semicircular canals, especially the left side was like a sac formation (Figure , arrow) as seen on the MRI findings. The bilateral cochleae and IACs showed normal bony constructions. Although there was no evidence of IAC stenosis (Figure , arrow heads), the mastoid segment of the fallopian canal on the left side was almost absent, and the tympanic segment was very narrow (Figure , arrow). She was diagnosed as having congenital unilateral aplasia of the facial nerve. MRI and CT findings suggested a hypoplastic disorder of the left facial nerve during development.

Figure 3. (a) High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) demonstrated bilateral hypoplasia of semicircular canals (especially, the left side was like a sac formation), (arrow). (b) Axial HRCT shows the fallopian canal on the right side is normal, but on the left side the tympanic segment is very narrow (arrow).

Discussion

Birth trauma is the most frequent cause (78–91%) of congenital unilateral facial paralysis.[Citation1–3] In traumatic cases, a history of forceps delivery, prolonged labor, evidence of periauricular ecchymoses or hemotympanum, or a birth weight greater than 3500g are risk factors for transient unilateral facial paralysis.[Citation4] Developmental disorders are divided into syndromes and isolated. Syndromes include Goldenhar syndrome, Treacher–Collins syndrome, and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (such as Möbius syndrome). Facial nerve deficiency/aplasia is one reason for isolated developmental congenital facial nerve paralysis.[Citation5]

Neuroimaging analysis has not been used to identify facial nerve characteristics until recently. Conventional MRI and 3D-CISS MRI are therefore valuable examinations for the early differential diagnosis of congenital disorders of the facial nucleus and nerve from birth trauma. 3D-CISS MRI gives high contrast for cerebrospinal fluid and shows a filling defect,[Citation7] and it usually shows facial nerves in the IAC with clear distinction from the cochlear-vestibular nerves. 3D-CISS MRI indicated the aplasia of the facial nerve in the IAC in the present study. It was difficult to prove facial nerve aplasia by conventional MRI or CT. 3D-CISS MRI could therefore be a valuable tool for the early differentiation of congenital facial nerve aplasia from birth injury. MRI images have limited application in the evaluation of congenital temporal bone abnormalities, but HRCT scanning offers excellent resolution of the temporal bone and fallopian canal in the bone when compared to conventional CT scans. HRCT makes it possible to diagnose facial nerve and cochlea-vestibular anomalies and observe the anatomical relationship between these structures.[Citation8] From the perspective of radiation exposure, it is not the primary diagnostic tool for children’s facial nerve aplasia. 3D-CISS MRI and HRCT confirmed that a developmental malformation of the unilateral facial nerve was the pathogenic condition in this patient. The nerves in the IAC are best evaluated on images made perpendicular to the IAC.[Citation9,Citation10] In this patient, the left facial nerve was almost absent.

Congenital facial nerve aplasia (deficiency) is considered to be a very rare condition, but it may be more frequent in cases with delayed or irreversible recovery from congenital facial paralysis using these medical technologies. 3D-CISS MRI and HRCT are very useful for diagnosing to distinguish facial nerve aplasia from other congenital causes in cases of delayed/irreversible recovery. From the perspective of radiation exposure, MRI including 3D-CISS should be the primary diagnostic tool for imaging children with congenital unilateral facial nerve paralysis.

Conclusion

Congenital unilateral facial paralysis is the result of many conditions, and conventional MRI and 3D-CISS MRI are the primary diagnostic tools in cases with delayed/irreversible recovery to diagnose congenital facial nerve aplasia. By using these tools, we can distinguish the facial nerve aplasia from facial paralysis caused by a traumatic injury.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are response for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Smith JD, Crumley RL, Harker LA. Facial paralysis in the newborn. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:1021–1024.

- Toelle SP, Boltshauser E. Long-term outcome in children with congenital unilateral facial nerve palsy. Neuropediatrics. 2001;32:130–135.

- Falco NA, Eriksson E. Facial nerve palsy in the newborn: incidence and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:1–4.

- Shapiro NL, Cunningham MJ, Parikh SR, et al. Congenital unilateral facial paralysis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:261–264.

- Pavlou E, Gkampeta A, Arampatzi M. Facial nerve palsy in childhood. Brain Dev. 2011;33:644–650.

- Terzis JK, Anesti K. Experience with developmental facial paralysis: part I. Diagnosis and associated stigmata. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:488–497.

- Hwang JY, Yoon HK, Lee JH, et al. Cranial nerve disorders in children: MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2016;36:1178–1194.

- Held P, Fellner C, Fellner F, et al. MRI of inner ear and facial nerve pathology using 3D MP-RAGE and 3D CISS sequences. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:558–566.

- Sasaki M, Imamura Y, Sato N. Magnetic resonance imaging in congenital facial palsy. Brain Dev. 2008;30:206–210.

- Casselman JW, Offeciers EF, Foer B, et al. CT and MR imaging of congential abnormalities of the inner ear and internal auditory canal. Eur J Radiol. 2001;40:94–104.