Abstract

Penetrating injuries of the neck are life-threatening injuries which constitutes 5–10% of all emergency consultations. Numerous vital structures, vascular, neurologic, digestive tract and airway injuries resulted in mortality rates up to 35%. The need for an emergency neck exploration or selective surgery after investigation remains a controversy. We present a case of penetrating neck injury undetected by Computer Tomography (CT) scan, requiring urgent neck exploration.

Introduction

Penetrating neck wounds are frequently seen in the Emergency Trauma. The extent of neck injuries can be underestimated by the location of the wound alone, and extensive injuries which involve multiple zones can occur with a seemingly superficial neck wound. Patients with neck injuries should be managed according to trauma principles. Once airway, breathing and circulatory parameters are stabilised, available diagnostic radiological imaging is promptly carried out. The author recommends, in the advent of high clinical index of suspicion, regardless of negative radiological findings, an urgent neck exploration is warranted. We present a case where, a tracheal injury was not picked up on CT scan, but due diligence of surgeons has spared a patient’s life.

Case report

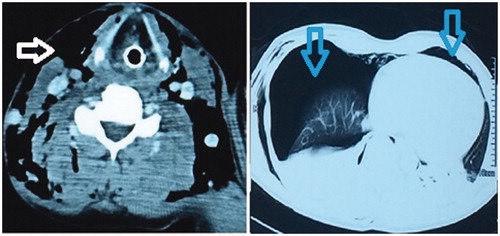

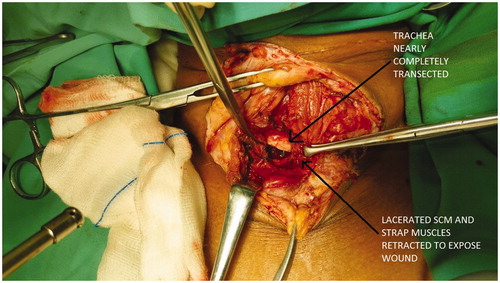

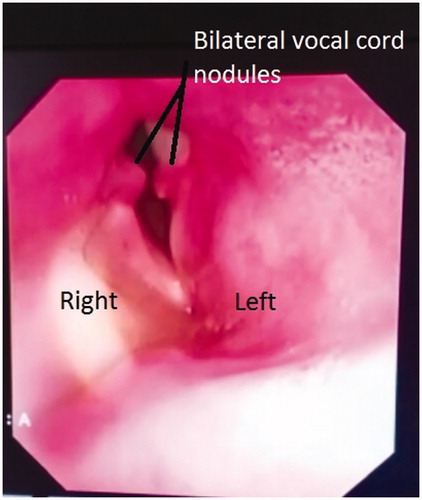

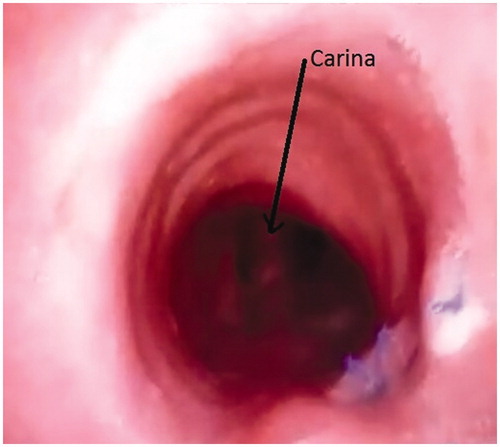

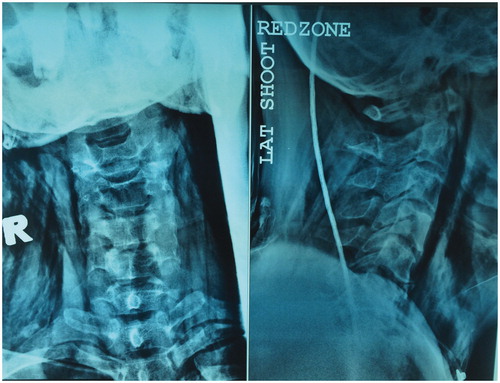

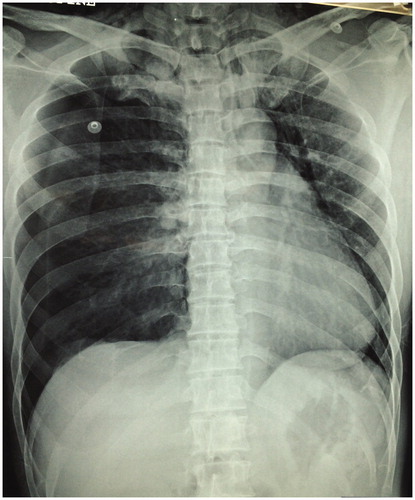

A 37-year-old male presented with multiple lacerations over the left side of the neck (Zone I), right anterior chest, left shoulder and left post auricular region secondary to assault using a machete. He was unable to maintain saturation and had extensive crepitus extending from bilateral mastoid region to the anterior chest. Neck radiograph showed extensive subcutaneous emphysema; chest radiograph showed bilateral tension pneumothorax with heart medialisation to the left (Figures and ). Bilateral chest tube was inserted and patient intubated. CT scan reported extensive soft tissue emphysema. Bilateral pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum with right lung contusion, bilateral lower lobes collapse-consolidation and mediastinal shift to the left unable to rule out tracheal or oesophageal injury (Figure ). A flexible bronchoscopy revealed a linear tear of the trachea 8 cm above the carina. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGDS) noted an anterior oesophageal perforation at the post cricoid region. An emergency neck exploration was done by extension of the preexisting neck wound, which revealed lacerations involving the left clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid, left strap muscles, left thyroid lobe and a 2/3 circumferential tear of the trachea (Figure ). The tracheal injury was repaired with polypropylene 2/0 interrupted sutures. Intraoperative OGDS, however, yields negative findings correlating with a negative Jacuzzi test. Patient was successfully extubated after 12 days. A flexible scope revealed bilateral posterior 1/3 vocal cord nodules and right vocal cord palsy (Figure ). He was started on proton pump inhibitors. Repeated bronchoscopy showed intact sutures at proximal trachea with minimal granulation tissue (Figure ). No tracheal stenosis noted. On assessment three months later, he recovered well.

Figure 1. Anteroposterior and lateral view of neck radiograph showing extensive subcutaneous emphysema.

Figure 2. Chest radiograph showing bilateral pneumothorax with medialization of the heart to the left.

Discussion

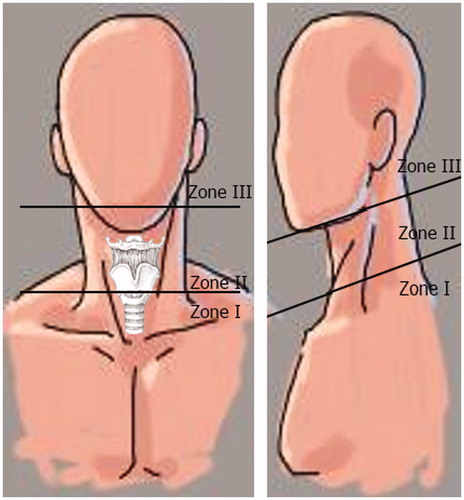

The anatomical division of the neck is described as three zones. Zone I extends from the base of the neck inferiorly till cricoid cartilage superiorly, Zone II extends from the cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible superiorly and Zone III encompasses the superior aspect of the neck from the angle of the mandible till the base of the skull (Figure ). These zones have been used as a guide to the approach of the management of neck injuries operatively.

Penetrating neck wounds are multifactorial, from motor vehicle accidents to gun-shot and knife wounds, where stab wounds account for 1–2%, gunshot wounds 5–10% and rifles cause 50% of the deaths in the United States.[Citation1] Patients with penetrating neck trauma should be stabilised prior to any diagnostic imaging. Neck and chest radiographs may thereafter be taken.

In 2008, the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) issued a guideline for penetrating neck traumas proposing that all hemodynamically stable patients should undergo CT Angiography (CTA) as the initial study of choice, particularly for zone I and zone III injuries which are more difficult to evaluate by physical examination.[Citation2] CTA not only detects vascular injury, but also demonstrated a high sensitivity for identifying aerodigestive tract injuries.[Citation3] Sperry et al. devised an algorithm for penetrating neck wounds, recommending those with Zone I and II injuries with no direct evidence of aerodigestive tract injury on CTA, should undergo oesophagography or oesophagoscopy if clinical suspicion exists.[Citation3] However, CTA may be time consuming and not ideal in an emergency setting. Bronchoscopy and oesophagoscopy may aid in diagnosis, but is operator dependent and small wounds may be missed. Our patient benefitted from a flexible bronchoscopy by identifying the site of tracheal injury which was not picked up on the CT scan. In contrast, oesophagoscopy yielded false results.

Nonoperative management of penetrating neck wounds prevailed in the early twentieth century.[Citation2] In 1956, Fogelman and Stewart suggested that mandatory exploration led to less mortality than mere observation, as studies showed that clinical symptoms were not present in 0–23% of cases.[Citation2,Citation4] As shown in this case, discrepancies between preoperative investigations and intraoperative findings still occur despite using the best available modalities. Kaya et al. series reported 66% of patients with penetrating neck wounds had laryngeal injuries, 33% had minor vascular injuries and 0% had oesophageal injuries.[Citation5] In the Demetriades et al. series, 15% had vascular injuries, 10% had laryngotracheal injuries and 7% had oesophageal injuries.[Citation6] Our patient underwent neck exploration, where multiple injuries were accurately identified and repaired. Patient was kept intubated and started on Ryle’s tube feeding postoperatively to assist in wound healing.

Conclusions

Penetrating neck traumas can cause high mortality rates. Tisherman et al. reported mandatory exploration yield negative findings in 53–60% of the time with no identification of any injuries.[Citation2] However, negative neck explorations have little morbidity,[Citation2] and is worthwhile to consider where doubt exists or clinically high index of suspicion, with or without the aid of imagery and endoscopic investigations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Health, Malaysia for allowing usage of patient’s records.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Jurkovich GJ. Definitive care phase: neck injuries. In: Lazar MWM, Greenfield LZ, Oldham JK, editors. Surgery-scientific principle and practice. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. p. 311–319.

- Tisherman SA, Bokhari F, Collier B, et al. Clinical practice guideline: penetrating zone II neck trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64:1392–1405.

- Sperry JL, Moore EE, Coimbra R, et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: penetrating neck trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:936–940.

- Fogelman M, Stewart R. Penetrating wounds of the neck. Am J Surg. 1956;9:581–596.

- Kaya KH, Koc AK, Uzut M, et al. Timely management of penetrating neck trauma: report of three cases. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:289–292.

- Demetriades D, Charalambides D, Lakhoo M. Physical examination and selective conservative management in patients with penetrating injuries of the neck. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1534–1536.