Abstract

Isolated nasal schwannomas are rare lesions that can be difficult to diagnose due to nonspecific characteristics. We report a unique case of a patient with a polypoid mass abutting the lacrimal sac found to be a nasal schwanomma. A 66-year-old male with a history of previously resected nasal polyposis returned to the office complaining of symptoms suggestive of rhinosinusitis. Endoscopy was significant for a polypoid mass superior to the inferior turbinate. CT imaging revealed a 2 × 1.8 × 1.3 cm lesion in the right nasal cavity with bony erosion overlying the lacrimal sac. Following endoscopic resection, pathologic analysis revealed a nasal schwanomma based on S100 and Ki-67 staining patterns. The patient has been doing well for over 6 months without recurrence. Although rare, nasal schwanomma should be kept in the differential of any nasal mass, and endoscopic resection can serve as a useful tool in the management of this disorder.

Introduction

Schwannomas are rare slow-growing tumors commonly associated with spinal or cranial sensory nerves. These tumors occur in the head and neck in up to 45% of cases, and most commonly develop from the eighth cranial nerve [Citation1]. In 4% of cases, schwanommas occur in the nose and paranasal sinuses [Citation2]. They are found more frequently in the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses compared to the sphenoid sinus or the nasal cavity. Schwanommas can develop in any age group, and do not display a preponderance to race or sex. Common presenting symptoms of nasal schwannomas include nasal obstruction, epistaxis, anosmia, facial swelling, pain, and chronic rhinitis [Citation3].

Schwanommas are hypothesized to develop from nerve sheaths formed by Schwann cells and perineural connective cells. Isolated nasal schwannomas are very rare tumors thought to arise from branches of the trigeminal nerve and autonomic ganglia [Citation3,4]. The optic and olfactory nerves are unlikely origin sites for schwannomas because their nerve sheaths are made of oligodendrocytes [Citation5]. It should be noted that the fila olfactoria acquire a Schwann cell sheath at approximately 0.5 mm beyond the level of the olfactory bulb and has the potential to give rise to a schwannoma [Citation6].

Here, we present an unusual case of a nasal schwanomma in a 66-year-old male and describe the endoscopic resection performed to successfully treat this patient.

Case presentation

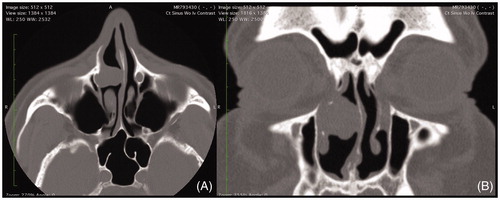

A 66-year-old Caucasian male with a previous history of nasal polyposis treated with polypectomy in the remote past presented for evaluation of chronic rhinosinusitis. He denied facial pain, pressure, headache, postnasal drip, rhinorrhea, anosmia, and dysgeusia. There was no recent use of nasal irrigations or nasal steroids. Pertinent past medical history included sinusitis, sleep apnea, and hypertension. Social history was significant for a 26-pack-year history of tobacco abuse. On physical exam, there were no external nasal lesions or deformity. Nasal endoscopy was significant for moderate septal deviation to the left, edematous mucosa throughout bilateral nasal cavities, and a clear nasopharynx. The middle and inferior meatuses were clear bilaterally. In the right nasal cavity, a papillomatous mass was visualized on the lateral nasal wall just superior to the inferior turbinate attachment, anterior to the head of the middle turbinate and uncinate process. A noncontrast CT scan of the sinuses revealed a homogenous mass in the right nasal cavity anterior to the middle turbinate measuring 2 × 1.8 × 1.3 cm in size (). The bone between the mass and the lacrimal sac was absent. A significant leftward septal deviation was noted, likely developing from the mass effect from the lesion in the nasal cavity. Imaging further revealed mild mucosal thickening of the right maxillary sinus consistent with chronic sinusitis.

Figure 1. (A) Axial and (B) coronal computed tomography imaging of homogenous right nasal mass abutting lacrimal apparatus and causing mass effect with septal deviation.

Ophthalmology was consulted given the possibility that the mass arose from the nasolacrimal duct and/or lacrimal sac. The patient had no ophthalmologic history, and did not have any related symptoms. External exam showed no reflux pressure over either lacrimal sac. Following punctal dilatation, nasolacrimal irrigation through the right lower punctum confirmed patency of the nasolacrimal duct. The consulting ophthalmologist concluded that the mass was likely of primary nasal origin and not of lacrimal origin. It was hypothesized that the mass exerted chronic pressure causing secondary atrophy and erosion of the intervening bone without resulting in nasolacrimal obstruction. In conjunction with ophthalmology, the decision was made to pursue endoscopic transnasal resection of the mass with concurrent dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR)/lacrimal sac biopsy as a diagnostic and therapeutic measure.

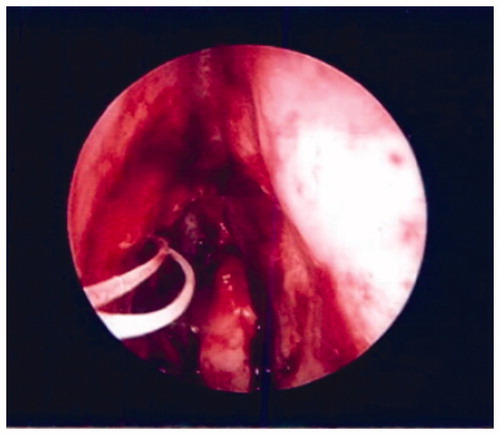

After initiation of general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation, the nose was injected with a 1% lidocaine and 1:100,000 epinephrine solution and then packed with Afrin-soaked pledgets. The Medtronic fusion image guidance system was calibrated and accuracy was confirmed. Intraoperative endoscopic examination of the right nasal cavity confirmed an erythematous, polypoid appearing mass abutting the lateral nasal wall anterior to the middle turbinate (). The lesion was first delineated and mucosal cuts were outlined anteriorly around the lesion using a curved beaver blade leaving a rim of normal tissue. The dissection proceeded along a submucoperiosteal plane at the anterior aspect of the lesion along the lacrimal and maxillary bone. The mass was raised off the bone from an anterior to posterior direction. Posterior, superior, and inferior mucosal cuts were then made using the curved beaver blade and endoscopic scissor. No evidence of bony ingrowth was noted during the dissection.

Following gross resection, a standard uncinectomy, maxillary antrostromy, and anterior ethmoidectomy were conducted. Upon exposure of the lacrimal sac, a distinct plane between the sac and the mass could not be confirmed so the decision was made to expose the entirety of the sac. A section of maxillary and lacrimal bone was then drilled and removed piecemeal using angled Kerrison rongeurs. An ophthalmologist then performed a DCR with lacrimal sac biopsy and placed a silastic stent in the right lacrimal system to maintain patency (). Hemostasis was obtained with the suction cautery device. No significant bleeding was noted postoperatively and the patient was discharged the same day in stable condition.

Figure 3. Postoperative image of nasal cavity following mass resection and placement of silastic stent.

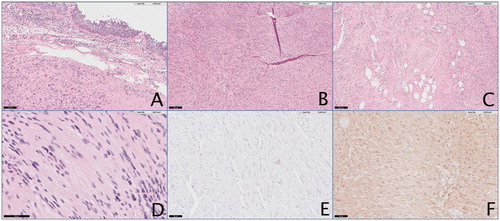

Frozen section analysis of the mass revealed a fragmented, well-encapsulated, lobulated white-tan mass weighing 3.8 g, measuring 2 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm in aggregate. It showed strong positive immunohistochemical staining for S100 and Ki-67 protein expression typical of Schwann cells. On microscopy, palisading Verocay bodies with Antoni A and Antoni B areas were visualized focally. Pathologic analyses of the mass are displayed in . Based on histopathological examination and imaging studies, a final diagnosis of isolated nasal schwannoma was made. The postoperative course was unremarkable. Nine months postoperatively, the surgical sites were healed well and there was no evidence of recurrence.

Figure 4. Pathology analysis of nasal mass using multiple stains to delineate nasal schwannoma. (A) 10×, view of nasal mass with nasal mucosa stained with hematoxylin/eosin. (B) 5× view identifying Antoni A areas. (C) 5× view identifying Antoni B areas. (D) 5× view showing Verocay bodies. (E) 20× view showing strong staining for Ki-67. (F) 20× view staining positively for S-100.

Discussion

Schwannomas are benign tumors accounting for approximately 8% of all intracranial tumors. They are exceedingly rare in the sinonasal tract and uncommonly considered when treating a nasal mass. They can fluctuate in size and may cause mass effect on surrounding structures. Bone remodeling, as demonstrated by this case, may be appreciated on imaging. Unlike nonenhancing necrotic and cystic masses, a Schwannoma’s vascular supply may display peripheral enhancement following contrast administration [Citation7]. If the tumor outgrows its blood supply, it undergoes cystic degeneration.

This case of nasal schwannoma is unique because of its location, hypothesized origin from branches of the trigeminal nerve and autonomic ganglia, and disease progression. CT imaging demonstrated a homogenous mass immediately lateral to the nasolacrimal duct, below the level of the lacrimal sac without evidence of cystic degeneration. It caused chronic rhinitis and sinusitis in this patient secondary to obstruction, pressure atrophy on the surrounding bone, and septal deviation to the left.

Accurate diagnosis of nasal schwannoma is challenging based solely on symptom presentation and radiograph findings as demonstrated by this case. Definite diagnosis requires thorough histopathological examination. Schwannomas are biphasic tumors comprised Antoni type A and Antoni type B areas in varying proportions. Antoni type A cells are well differentiated, spindle-shaped cells. Their nuclei are organized in palisading rows around fibrillary processes known as Verocay bodies. In contrast, Antoni type B areas are hypocellular with poorly differentiated cells in a loose, myxoid stroma. Mitotic figures are rare in both regions. Schwannomas show strong positive immunostaining for S100 protein and negatively stain for keratin, neurofilament, and desmin. In regions other than the paranasal tract, schwannomas are covered in a fibrous capsule formed from epineurium and residual nerve fibers [Citation8,Citation9].

Rarely, patients with neurofibromatosis have been reported to develop nerve sheath tumors in the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. With this in mind, care should be taken to exclude neurofibromatosis in patients with schwannomas of the sinonasal tract. Schwannomas rarely undergo malignant transformation. Regardless of their location, they are best treated with surgical excision, which is often curative [Citation10]. Radiographic studies are recommended to exclude skull base defects and preoperative tissue diagnosis helps plan the surgical intervention. Generally, prognosis is excellent.

In conclusion, we report a 66-year-old male patient with unilateral nasal cavity schwannoma adjacent to the lacrimal sac treated with transnasal endoscopic excision as a therapeutic and diagnostic adjunct. Patients with unilateral nasal masses should be approached with a broad differential in mind, keeping nasal schwannoma as a possibility despite its rare incidence. Preoperative biopsy can differentiate these rare pathologies from more common lesions such as inverted papilloma and antrochoanal polyps. Multidisciplinary care is of utmost importance in the management of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Eric Vail and Humayun Islam, Department of Pathology at West Chester Medical Center, for providing pathology images for the reported case.

Disclosure statement

No conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

This paper has not been submitted nor is being considered for publication in other journals

Compliant with ethical standards was met.

References

- Suh JD, Ramakrishnan VR, Zhang PJ, et al. Diagnosis and endoscopic management of sinonasal schwannomas. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2011;73:308–312.

- Gencarelli J, Rourke R, Ross T, et al. Atypical presentation of sinonasal cellular schwannoma: a nonsolitary mass with osseous, orbital, and intracranial invasion. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2014;75:e144–e148.

- Berlucchi M, Piazza C, Blanzuoli L, et al. Schwannoma of the nasal septum: a case report with review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257:402–405.

- Buob D, Wacrenier A, Chevalier D, et al. Schwannoma of the sinonasal tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 5 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1196–1199.

- Pasic TR, Makielski K. Nasal schwannoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103:943–946.

- Oi H, Watanabe Y, Shojaku H, et al. Nasal septal neurinoma. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1993;504:151–154.

- Enion DS, Jenkins A, Miles JB, et al. Intracranial extension of a naso-ethmoid schwannoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:578–581.

- Kim YS, Kim HJ, Kim CH, et al. CT and MR imaging findings of sinonasal schwannoma: a review of 12 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:628–633.

- Figueiredo EG, Soga Y, Amorim RLO, et al. The puzzling olfactory groove schwannoma: a systematic review. Skull Base. 2011;21:31–36.

- Hegazy HM, Snyderman CH, Fan CY, et al. Neurilemmomas of the paranasal sinuses. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:215–218.