Abstract

Giant cell granulomas (GCG) are rare tumors affecting the head and neck region and other sites of the body. Their occurrence in the hard palate is highly uncommon. We present the case of a 15-year-old female patient who presented with a hard palate mass that was confirmed to be a GCG following surgical excision. A review of all cases of GCG in the hard palate reported in the literature till date is presented with an update on differential diagnosis and treatment modalities.

Introduction

Giant cell granulomas (GCG) are rare benign tumors that can affect the head and neck region. GCG comprise 0.1% of all tumors of facial bones [Citation1]. Giant cell tumor (GCT), which is a well-defined entity, occurs mainly in long bones. However, GCG of the jaw is a different entity described mainly in the mandible [Citation2]. GCG of the hard palate remain a rare occurrence [Citation3]. GCT and GCG of the jaws are usually considered as the development of a single pathologic process that may be influenced by patient’s age, location and other unknown factors [Citation2,Citation4].

In the craniofacial skeleton, GCG can be central or peripheral. Peripheral GCG are more common, arising from periosteum or connective tissue as part of the alveolar ridge and gingival mucosa [Citation5]. In contrast, central GCGs (CGCGs) are less common and are endosteal in origin meaning that they arise from within the cortex [Citation3]. Both lesions affect the mandible more commonly than the maxilla, with one report of 26 cases of GCG of the facial bones showing that 61.5% of lesions diagnosed were in the mandible while 38.5% were found in the maxilla [Citation1].

In 1953, Jaffe coined the term ‘giant cell reparative granuloma’ to differentiate what he believed represented a local tissue reaction to trauma or hemorrhage from an actual neoplastic process [Citation2]. Current nomenclature omits the word reparative because of the locally destructive, invasive, and enlarging nature of the growths. Furthermore, most reported cases are without antecedent trauma [Citation3].

CGCG mainly occur close to or in the alveolar process of the anterior mandible and maxilla. Less frequently, lesions will occur in the posterior maxilla and hard palate [Citation3].

We hereby present a case of CGCG of the hard palate along with a review of the literature including all previously reported cases of CGCG of the hard palate.

Case

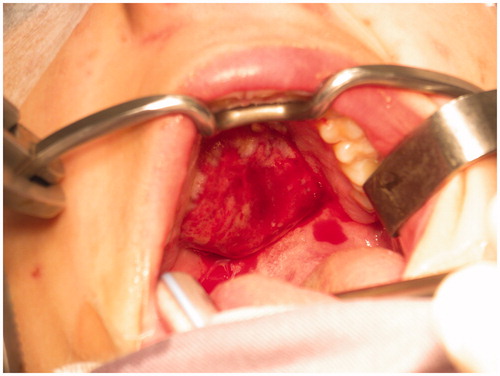

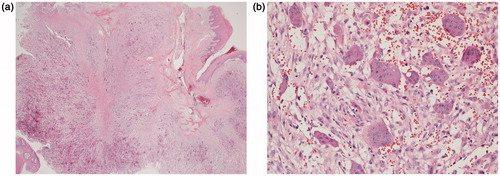

A 15-year-old female with no particular past medical history, presented with right nasal obstruction and a progressively growing mass of the hard palate. The mass was neither tender nor painful and caused mild discomfort during meals. On physical exam, an indurated, nonulcerative and exophytic lesion was found on the hard palate (Figure ). A bulging in the right nasal fossa floor was seen. The rest of the exam was within normal limits. CT scan of the sinuses showed a 3-cm irregular mass in the right palate extending to the nasal cavity, in close contact with the inferior nasal turbinates and associated with moderate lysis of the bony palate (Figure ). A biopsy was done in another hospital and showed a GCG. The patient was then admitted to our department and excision of the palatal mass was done through a transoral approach. During surgery, the nasal mucosa covering the bulging mass in the nasal cavity was preserved. Since no oro-nasal communication was created, the defect in the hard palate was packed and left to heal with secondary intention. Histopathological examination of the surgical specimen confirmed the initial diagnosis. In a background rich in multinucleated osteoclastic-like giant cells, a proliferation made of round or spindle cells with mild atypia was seen. This proliferation infiltrates palatal bone and extends under the palatal mucosa. Red blood cells extravasation was prominent but did not show neither cystic spaces nor amorphous calcifications with chondroid aura. Immunohistologic staining was negative for p63 (Figure ). A complete parathyroid and electrolytes blood work was done and was within normal limits. The patient had no evidence of cherubism or neurofibromatosis type I.

Discussion

GCG was first described by Jaffe in 1953 as a giant cell reparative granuloma of the jaw bones. He suggested an association between previous trauma and GCG formation [Citation2]. However, this could not be confirmed in all the cases described later in the literature [Citation3]. Stavropoulos and Katz reported a 15% rate of GCG secondary to trauma in their series of 20 cases [Citation4]. The term ‘reparative’ has been abandoned since. In 2004, epidemiological findings of GCG in the general population were published [Citation5]: an incidence of 1.1 per 100 was found with a female predilection that was not as large as was earlier presumed (F/M = 2:1). GCG occurred more frequently in young population with peak incidence for males and females occurring respectively between 10–14 and 15–19 years of age. As reported earlier, the mandible was more frequently involved than the maxilla [Citation1,Citation5].

The diagnosis of CGCG is suspected when the clinical characteristics described earlier are present. Furthermore, radiologic findings are various and include a wide range of soft tissue lesions from small unilocular to large multilocular with or without displacement of teeth, root resorption and cortical erosion [Citation4]. The incidence of these findings varies between the different reported series. A systematic review of 232 well-established cases with histopathological confirmation of GCG revealed the following proportions: ill-defined borders (66%), multilocular (54%), teeth displacement (43%), cortical expansion (51%) and cortical erosion (38%) [Citation4]. Some authors described characteristic radiologic findings for CGCGs such as the presence of a subtle granular bone pattern at the periphery of the expanded bone or in internal septa within the lesion [Citation6].

Some genetic syndromes can also be associated with the presence of GCG: cherubism [Citation7], Noonan syndrome [Citation8] and neurofibromatosis type I [Citation9].

The histologic description of GCG includes multinucleated giant cells varying in size and their number of nuclei dispersed throughout a vascular stroma of epithelioid or spindled-shaped mononuclear cells [Citation10].

Aggressive GCG tend to grow fast and to recur. Some characteristic features define them: maxillary location, young age, pain, paresthesia, tooth root and cortical erosion [Citation11]. They are thus considered prognostic factors in terms of local invasion and recurrence after optimal treatment.

Surgery is considered as the gold standard for treatment of GCG with variable reported recurrence rates depending on the proportion of aggressive cases. Surgical resection is associated with recurrence rates of 5.6%–11.5% [Citation12] compared to simple curettage 12.5%–46% [Citation13]. Some reports exist on the efficacy of nonsurgical therapy including intralesional corticosteroids therapy [Citation14], calcitonin therapy [Citation15] and interferon alpha therapy [Citation16]. However, there is insufficient evidence supporting their use with or without the surgical resection [Citation17].

We report a case of 15-year-old girl with a rare location of CGCG. When presented with a tumor of the hard palate clinicians should evoke different possible origins: salivary glands, bone, nerves, and muscles [Citation10]. When histologic exam of that tumor reveals numerous giant cells the differential diagnosis should include: aneurysmal aneuvrysmal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, GCG, cherubism, type II neurofibromatosis and brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism [Citation6]. In our case, aneurysmal cyst bone was excluded due to the absence of cystic spaces and amorphous calcification with chondroid aura despite the presence of prominent red blood cells extravasation. The remaining possible diagnoses share the same histologic features. However, negative p63 staining excludes giant cell tumor; normal calcium, phosphorus and PTH values excludes brown tumor of parathyroidism; cherubism and neurofibromatosis type I were excluded due to the lack of characteristic clinical features. Therefore, the final diagnosis was central GCG of the hard palate.

The hard palate is a rare location for CGCG. Only 8 cases were previously reported in the literature [Citation11,Citation18–23] (Table ). Age varies from 12 to 65 years with a mean of 29 years. A CT scan was performed in all cases showing evidence of bone erosion in six cases and bone expansion in two cases. All cases were treated with surgical resection and one reported case received adjuvant treatment consisting of intralesional steroids. Three recurrences were noted with a rate of 37.5% (3/8). This rate was higher than the reported recurrence rates for CGCG of other locations following surgery (5.6%–11.5%) [Citation12].

Table 1. Review of all hard palate GCG cases reported in the literature.

In conclusion, the hard palate is a rare location of the CGCG and constitutes a diagnostic challenge. This site seems to be associated with an aggressive behavior based on the high incidence of bone erosion and recurrence. Radical surgery appears to be the gold standard for treatment with no evidence related to adjuvant treatment or other treatment modalities.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is not supported by any grant.

Disclosure statement

All authors have equal contribution and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Noleto JW, Marchiori E, Sampaio RK, et al. Aspectos radiológicos e epidemiológicos do granuloma central de células gigantes. Radiol Bras. 2007;40:167–171.

- Jaffe HL. Giant-cell reparative granuloma, traumatic bone cyst, and fibrous (fibro-oseous) dysplasia of the jawbones. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1953;6:159–175.

- Sidhu MS, Parkash H, Sidhu SS. Central giant cell granuloma of jaws-review of 19 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:43–46.

- Stavropoulos F, Katz J. Central giant cell granulomas: a systematic review of the radiographic characteristics with the addition of 20 new cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:213–217.

- De Lange J, van den Akker HP, Klip H. Incidence and disease free survival after surgical therapy of central giant-cell granulomas of the jaw in The Netherlands: 1990–1995. Head Neck. 2004;26:792–795.

- Jadu FM, Pharoah MJ, Lee L, et al. Central giant cell granuloma of the mandibular condyle: a case report and review of the literature. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2011;40:60–64.

- de Lange J, van Maarle MC, van den Akker HP, et al. DNA analysis of the SH3BP2 gene in patients with aggressive central giant cell granuloma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;45:499–500.

- Ucar B, Okten A, Mocan H, et al. Noonan syndrome associated with central giant cell granuloma. Clin Genet. 1998;53:411–414.

- Ardekian L, Manor R, Peled M, et al. Bilateral central giant cell granulomas in a patient with neurofibromatosis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.1999;57:869–872.

- van der Waal I. Diseases of the jaws, diagnosis and treatment. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1991. p. 55–60.

- Roberts J, Shores C, Rose AS. Surgical treatment is warranted in aggressive central giant cell granuloma: a report of 2 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88:E8–E13.

- Kruse-Losler B, Diallo R, Gaertner C, et al. Central giant cell granuloma of the jaws: a clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic study of 26 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:346–354.

- Andersen L, Fejerskov O, Philipsen HP. Oral giant cell granulomas. A clinical and histological study of 129 new cases. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1973;81:606–616.

- Carlos R, Sedano HO. Intralesional corticosteroids as an alternative treatment for central giant cell granuloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:161–166.

- Dominguez Cuadrado L, Martinez Gimeno C, Plasencia Delgado J, et al. Intranasal calcitonin therapy for central giant cell granuloma. J Cran Maxillofac Surg. 2004;32:244–245.

- Busaidy B, Wong MEK, Herzog C, et al. Alpha interferon in the management of central giant cell granuloma: early experiences. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:86–87.

- Suárez-Roa M de L, Reveiz L, Ruíz-Godoy Rivera LM, et al. Interventions for central giant cell granuloma (CGCG) of the jaws. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD007404.

- Edwards PC, Fantasia JE, Saini T, et al. Clinically aggressive central giant cell granulomas in two patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:765–772.

- Gunel C, Erpek G, Meteoglu I. Giant cell reparative granuloma in the hard palate. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2007;2:76–79.

- Hernandez HN, Lewiss RE, Yousem DM, et al. Central giant cell granuloma of the hard palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:871–873.

- Anand TS, Kumar D, Kumar S, et al. Giant cell tumor of hard palate. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;53:299–300.

- Kumar R, Marwah A, Gupta R, et al. Recurrent giant cell reparative granuloma of hard palate: role of Tc-99m-MDP three-phase bone scan. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:143–145.

- Moss S, Domingo J, Stratton D, et al. Slowly expanding palatal mass. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:655–659.