Abstract

Intersinus septal cells (ISSC) are defined as cells confined to the thin septum separating the frontal sinuses. In 2008, Som et al. first described four cases with a mucocele proved to have arisen in ISSC. Here, we report two cases with a mucocele in ISSC, representing the second report to appear in the English literature. Case 1 involved a mucocele in the center of the frontal lesion with rudimentary bilateral frontal sinuses, which suggested that the ISSC mucocele occurred during very early development of the frontal sinuses. Case 2 concerned a mucocele in the unilocular frontal sinus invading the left orbit. The frontal sinus septum was destroyed with partial ‘Y’-shaped remnants, which implied the ballooning and bursting of the ISSC mucocele into both sides of the frontal sinus. The two different mechanisms of development of the ISSC mucoceles may vary in relation to the time of onset.

Introduction

It is common for frontal sinus mucoceles to arise on one side of the frontal sinuses and if frontal table thinning is off midline. In 2008, Som and Lawson reported the first four cases of mucocele that expanded the central cell in the frontal sinus and obstructed the more laterally positioned frontal sinus cavities [Citation1], all of which involved thinning of the midline anterior and/or posterior frontal sinus tables. Som proved surgically that these four mucoceles arose in intersinus septal cells (ISSC). We herein report two cases of frontal sinus mucoceles that were presumed to develop in ISSC, representing the second report in the English literature of mucoceles arising in ISSC. We also demonstrate two patterns of developing mechanisms that vary with the time of onset.

Case reports

Case 1

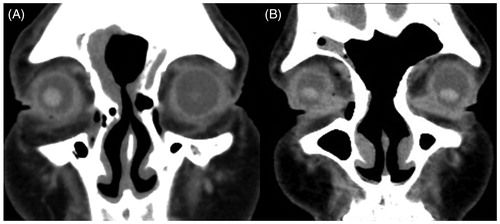

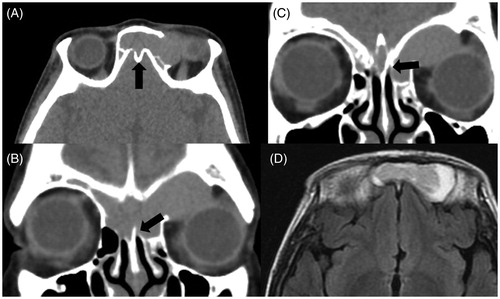

A 77-year-old woman consulted a local doctor with a chief complaint of frontal swelling. MRI findings showed a cystic lesion of the frontal sinus, and she was referred to our hospital for surgical treatment. The patient had no history of nasal–paranasal surgery or facial injury. She presented with a painless, elastic hard mass with no mobility in the forehead. CT findings showed the presence of a cystic lesion in the center of the frontal sinus with thinning of the posterior frontal table (Figure ). The frontal mass showed heterogeneous moderate to high intensity on T1-weighted MRI and moderate to low intensity on T2-weighted imaging (Figure ). These findings were compatible with a mucocele, and the patient was initially diagnosed as having frontal sinus mucocele. However, the remnants of the bilateral small frontal sinuses were located on both sides of the cyst, on the right side with air and on the left with soft tissue (Figure ). The mucocele was considered to originate from ISSC, and the lesion and the obstruction and pneumatization of the bilateral frontal sinuses was presumed to have started very early in the development of the frontal sinus. We performed endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) with a modified Lothrop procedure to drill out the outflow tract. First of all, we identified the wall of mucocele at the anterior base of right middle turbinate. The wall was thick and the content of the mucocele comprised mucous clear liquid and yellow clay-like material. The lesion was unilocular with a large deficiency of the posterior wall, in other words, anterior skull base. The pathological examination revealed that the wall of the mucocele consisted of connective tissue with no epithelium lining inside. Although the outflow tract was narrowed by scar tissue because of insufficient drill out of the frontal table, patency has been maintained for more than 3 years since surgery (Figure ).

Figure 1. Axial CT showed a mucocele on the center of the frontal lesion, thinning the rear bony wall of the frontal table in the midline (A). MRI showed that the frontal mass had heterogeneous moderate to high intensity on T1-weighted and moderate to low intensity on T2-weighted imaging (B, C). The remnants of the bilateral small frontal sinuses were located on the both sides of the cyst, on the right side with air (A, D: white arrows) and on the left side with soft tissue (E: black arrow).

Case 2

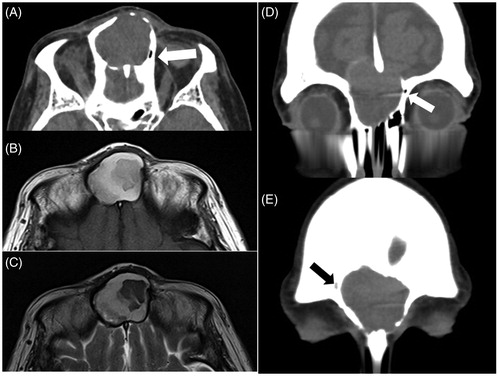

A 55-year-old woman was admitted to an ophthalmology clinic for left eye pain. MRI findings showed a cystic lesion of the frontal sinus, and she was referred to our hospital for surgical treatment. She had no history of nasal–paranasal surgery or facial injury. CT findings showed that the lesion existed in both frontal sinuses and invaded the left orbit by destroying the orbital roof (Figure ). MRI findings showed a moderate-intensity mass surrounded by a high-intensity area on T1-weighted imaging (Figure ), which suggested that a unilocular mucocele originating in the middle of the frontal lesion and extending to both sides. The frontal sinus septum was destroyed with ‘Y’-shaped remnants on the coronal CT view, suggesting the ballooning and bursting of the ISSC mucocele into both sides of the frontal sinus (Figure ). Moreover, there was a ‘niche’ at the center of the frontal skull base instead of the frontal septum (Figure ), which also supported the idea that the mucocele originated in ISSC. The lesion was considered to arise after sufficient pneumatization of the frontal sinus. We performed ESS with a modified Lothrop procedure to drill out the outflow tract. Differently from Case 1, the wall of mucocele was thin and we did not keep samples for pathological examination. The content of the mucocele was mucopurulent, and the lesion was unilocular with deficiency of the left orbital roof. In this case, the bony wall of anterior skull base kept intact. The patency of the tract has been maintained for 2 years since the operation (Figure ).

Figure 2. CT demonstrated that the lesion existed in both of the frontal sinuses, invading the left orbit by destroying the orbital roof (A), and there was a ‘niche’ at the center of the frontal skull base instead of the frontal septum (A: black arrow). The frontal sinus septum was mostly destroyed but partially remained in a ‘Y’ shape, which implied ballooning and bursting of the mucocele of ISSC into both sides of the frontal sinus (B, C: black arrow). MRI showed a moderate-intensity mass in the middle of the frontal lesion surrounded by a high-intensity area on T1-weighted imaging (D).

Discussion

An ISSC was defined by Van Alyea in 1941 as a cell confined to the thin septum separating the frontal sinuses [Citation2], which was present in 28 (12%) of his 242 dissection specimens. Merrit et al. identified ISSC in 34% of their series of coronal CT scans of 300 heads [Citation3]. The frontal sinus is generated from the dropout of the central bone marrow of the frontal bone to aerate and divide into left and right, while the remaining midline partition forms the frontal septum [Citation4]. The generation period has been reported to be 3–4 fetal months. Occasionally the frontal sinuses develop from an ethmoid cell migrating from the ethmoid infundibulum, and these combined patterns of development may result in multiple sinuses on each side [Citation2]. Regarding the origin of ISSC, Som and Lawson considered that the majority of ISSC arise from the frontal sinus and not as a result of migration, because 85% of their series of ISSC communicated anteromedially with either or both frontal sinuses [Citation5]. Wang et al. dichotomized ISSC into Type I, communicating with at least one frontal sinus, and Type II, with no communication to either frontal sinus [Citation6]. Type I cells are presumed to arise from a frontal sinus and Type II are assumed to be displaced cells of ethmoid origin. According to their report, the prevalence of ISSC was higher in Chinese patients (45%), with Type II (27%) more frequent than Type I (19%).

Although ISSC itself is not a rare occurrence, there has been only one report of cystic lesions in ISSC [Citation1]. Som and Lawson defined the imaging features of the mucocele in ISSC as follows: (1) the cysts with left and right compressed frontal sinuses exist on the midline of the frontal bone; (2) findings suggest that the front and/or rear of the frontal table is thinning at the midline [Citation1]. Here, we report two cases of frontal mucoceles suspected of arising from ISSC with differing pathogenesis. We consider that the differences between these two cases are related to two factors, the time of onset and signs of inflammation. In case 1, the mucocele was considered to be congenital because the bilateral frontal sinuses were rudimentary. The mucocele was considered to grow very slowly without the influence of inflammation. In case 2, there were well pneumatized frontal sinuses on both sides, which suggested that the mucocele occurred postnatally. The mucocele may be formed by obstruction of the drainage pathway to the frontal sinus, with subsequent bacterial infection causing expansion of the mucocele before it breaks into adjacent sinuses. Case 2 did not match either of the definitions of ISSC mucocele proposed by Som et al. because the mucocele in case 2 grew by breaking into, not by pushing, adjacent sinuses.

There was another difference between case 1 and case 2, the sites invaded by the mucoceles. In case 1, the mucocele collapsed the frontal base into the anterior cranial fossa. In case 2, the mucocele collapsed the orbital roof in the left. In case 1, there was supposed to be thick bony wall in front of orbit because the timing of the onset of mucocele was considered before the frontal sinuses were pneumatized. Eventually, the mucocele grew toward the anterior cranial fossa. In case 2, thinner bony walls at that timing, frontal sinus and orbital wall, may collapse easily in growing.

Unfortunately, we could not detect the mechanism of the obstruction of the drainage root in either case. Either case had no history of allergic rhinitis, head injury, or co-existed tumor of the anterior skull base, such as osteoma [Citation7].

The standard treatment of frontal mucocele is ESS, which often necessitates additional surgery for stenosis. Ting et al. reported that frontal drill out surgery by ESS needed reoperation due to stenosis in about 29.9% of patients 2 years postoperatively, and also commented that mucocele recurred at a higher rate (38.9%) than chronic frontal sinusitis [Citation8]. In the present cases, the patency of the tract has been maintained for 3 and 2 years, respectively, mainly because the location of the tract is at the center and bottom of the mucocele, which is sometimes widened by the mucocele itself.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Som PM, Lawson W. Interfrontal sinus septal cell: a cause of obstructing inflammation and mucoceles. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1369–1371.

- Van Alyea OE. Frontal cells: an anatomic study of these cells with consideration of their clinical significance. Arch Otol. 1941;34:11–23.

- Merrit R, Bent JP, Kuhn FA. The intersinus septal cell. Anatomic, radiologic, and clinical correlation. Am J Rhinol. 1996;10:299–302.

- Schaeffer JP. The genesis, development, and adult anatomy of the nasofrontal region in man. Am J Anat. 1916;20:125–146.

- Som PM, Lawson W. The frontal intersinus septal air cell: a new hypothesis of its origin. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1215–1217.

- Wang M, Yuan F, Qi WW, et al. Anatomy, classification of intersinus septal cell and its clinical significance in frontal sinus endoscopic surgery in Chinese subjects. Chin Med J. 2012;125:4470–4473.

- Sakamoto H, Tanaka T, Kato N, et al. Frontal sinus mucocele with intracranial extension associated with osteoma in the anterior cranial fossa. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015;51:600–603.

- Ting Y, Wu A, Metson R. Frontal sinus drillout (modified Lothrop procedure): long-term results in 204 patients. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1067–1071.