Abstract

Plexiform neurofibromas (PNs) are slow-growing, vascularised, limited, non-capsular benign tumours. They may cause functional impairments, cosmetic problems, and issues with pain or a sense of pressure. Involvement of the external ear canal, which can trigger conductive-type hearing loss and cosmetic problems, is rare. A 14-year-old male diagnosed with, and under follow-up for, type 1 neurofibromatosis presented with hearing loss and an auricle deformity caused by a mass on the postauricular region of the mastoid bone. This mass had grown gradually over the past 5 years and at the time of consultation completely filled the external ear canal, pushing the auricle forward. It was surgically removed. Postoperative histological examination allowed diagnosis of a plexiform neurofibroma. The external ear canal was successfully cleared, affording a good cosmetic outcome. Audiometric tests revealed that the air-bone gap had closed.

Introduction

Type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF; Von Recklinghausen’s disease) is an autosomal-dominant disease characterised by coffee-coloured stains on the skin, neurofibromas, and freckles [Citation1,Citation2]. The neurofibromas are histologically classified as localised, plexiform, and diffuse [Citation3]. Plexiform neurofibromas (PNs), which originate from peripheral nerve sheaths and may include nerve branches, are slow-growing, vascularised, limited, non-capsular benign tumours. However, they can transform into malignant, peripheral, nerve sheath tumours or malignant schwannomas. PNs commence development in early childhood, but the clinical findings become more obvious during growth to adolescence. Although PNs are most often noted on the trunk, the second most common location is the head-and-neck region. External ear canal involvement is rare and may be associated with conductive-type hearing loss [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4].

Type 2 NFs are usually bilateral vestibular schwannomas, rarely accompanied by skin pathologies, and are distinguished from other cranial nerve schwannomas and meningiomas [Citation1].

Case

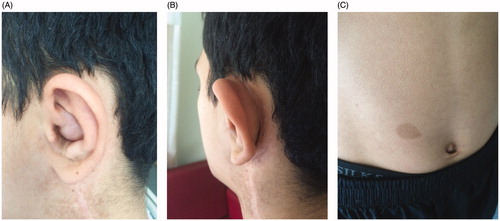

A 14-year-old male had been diagnosed with, and was under follow-up for, type 1 NF. He had undergone surgery to treat neck involvement at another centre. He then presented to our clinic because of hearing loss and an auricle deformity caused by a mass on the postauricular region of the mastoid bone. This had grown gradually over the past 5 years and at the time of consultation completely filled the external ear canal, pushing the auricle forward. On physical examination, a semi-mobile soft-textured mass was noted; this created a swelling measuring approximately 2 × 1 cm over the cavum concha of the anterior section of the auricle. This swelling completely closed the entrance to the external ear canal. In the retro-auricular region, the mass extended over the mastoid bone to the upper part of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Coffee-coloured stains were apparent on the skin (Figure ).

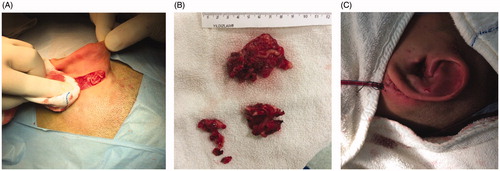

Figure 1. (A, B) A neurofibroma filling the external ear canal and pushing the auricle forward. C: Coffee-coloured stains on the skin.

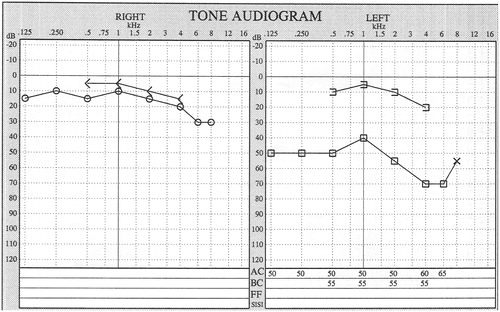

Audiometric examinations revealed conductive-type hearing loss. The hearing threshold levels were normal in the right ear and, in the left ear, the bone-pathway hearing threshold was also normal. The masked-airway, pure-tone, average hearing threshold was 48.3 dB and mild loss of conductive hearing was evident in the right ear (Figure ).

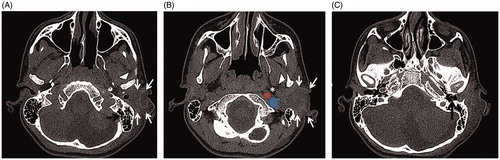

Computed tomography (CT) revealed a non-specific, infiltrative, irregularly hypodense, enhancing soft tissue mass measuring 43 × 28 × 26 mm located between the left region of the temporal bone mastoid and the mandible, adjacent to the superior parapharyngeal area, approaching within 3 mm of the annulus, and obliterating the external ear canal (Figure ). The mass did not extend to the middle ear. We planned surgical removal of it.

Figure 3. (A) On axial temporal bone CT, the right external ear canal is open. In the left ear, a soft tissue mass (white arrows) surrounds and obliterates the external ear canal between the region of the left temporal bone mastoid (black arrow) and the mandible (white arrowhead). (B) On the more inferior slices, the mass approximates the internal carotid artery (red circle), the internal jugular vein (blue circle), and the superior parapharyngeal area (star). (C) The mass approaches the annulus to within 3 mm (black arrow) and obliterates the external ear canal.

A postauricular incision was created and the mass was approached subcutaneously. The mass completely covered the mastoid bone, extended inferiorly toward the upper part of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and entered the external ear canal anteriorly. The mass measured approximately 5 × 4 × 3 cm, was red and white in colour, exhibited bleeding, lacked a capsule, and exhibited dense infiltration of surrounding tissue. Scattered soft areas were evident between the nodular areas, yielding the typical appearance of a ‘bag of worms’.

Pathological tests performed during the operation revealed that the vascular and fibrotic structures were benign. The operation was performed in two stages. First, the part of the mass extending from over the mastoid bone toward the upper section of the sternocleidomastoid muscle was removed and the external ear canal was entered under microscopic guidance. The mass extended to the membrane of the external ear canal. The tympanic membrane was intact. Via both blunt and sharp dissection (from the sides to the middle), the mass was excised together with skin of the external ear canal to which it was adherent, and some conchal cartilage. The remaining skin of the external ear canal and the residual conchal cartilage were suspended on the posterior region of the mastoid bone and meatoplasty was completed.

Blood loss during the operation totalled about 400 mL. The external ear canal was cleared and a good cosmetic outcome was attained (Figure ). A furacin tampon was placed in the external ear canal and removed after 15 days.

Figure 4. (A, B) A neurofibroma measuring approximately 5 × 4 × 3 cm, exhibited bleeding, lacked a capsule, and showed dense infiltration of the surrounding tissue. The neurofibroma was typical in appearance, resembling a ‘bag of worms’. (C) The external auditory canal after surgery.

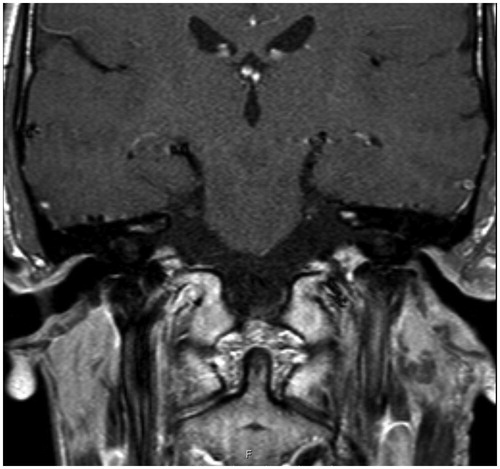

Postoperative histological evaluation allowed diagnosis of a plexiform neurofibroma. On audiometric testing 6 months after the surgical procedure, the bone-air gap had closed and hearing was within normal limits. A T1-weighted magnetic resonance image taken 2.5 years postoperatively showed that both external ear canals were open and the surrounding soft tissues were normal (Figure ).

Discussion

Neurofibroma formation and growth accelerate during periods of hormonal change, including puberty and pregnancy. Depending on the location of the growth, cosmetic problems, functional impairment, pain, and/or a sense of pressure may develop. Aesthetic disfigurement is the leading indicator for surgery, followed by pain and functional deficits [Citation5]. Although rare, conductive-type hearing loss and cosmetic problems can develop if the external ear canal is involved, creating a need for surgical removal. Complete resection of an infiltrative growth is difficult because of the general anatomy of the ear and haemorrhagic problems that may develop during excision. To minimise the possibility of recurrence, the most extensive excision possible should be planned [Citation3,Citation4].

As functional (hearing) loss and cosmetic problems had emerged during follow-up of our patient, we planned surgical excision. We created a wide excision to minimise the possibility of recurrence and attempted to prevent potential hearing loss by widening the external ear canal as much as possible. Postoperatively, the air-bone gap closed and a good cosmetic result was achieved. At the 2-year postoperative follow-up, no recurrence was observed (Figure ).

Conclusions

Neurofibromas are difficult to excise, being both non-capsular and rich in vascular structures. If removal is incomplete, relapse is very likely. It must be borne in mind that significant bleeding may develop during excision. Cosmetic or functional problems, especially in the head-and-neck region, complicate neurofibroma surgery to an even greater extent.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Geller M, Darrigo JLG, Bonalumi FA, et al. Plexiform neurofibroma in the ear canal of a patient with type I neurofibromatosis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75:158.

- Wise JB, Cryer JE, Belasco JB, et al. Management of head and neck plexiform neurofibromas in pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:712–718.

- Ghosh SK, Chakraborty D, Ranjan R, et al. Neurofibroma of the external ear - a case report. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;60:289–290.

- Minoda R, Ise M, Murakami D, et al. Surgical removal of diffuse-type neurofibroma involving the auditory external canal in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Int Adv Otol. 2012;8:497–502.

- Nguyen R, Ibrahim C, Reinhard E, et al. Growth behavior of plexiform neurofibromas after surgery. Genet Med. 2013;15:691–697.