Abstract

Angiectatic nasal polyp (ANP) is a rare entity of inflammatory sinonasal polyps, constituting only 4–5% of all nasal polyps. Clinically, this rare entity closely simulates hemangiomas, inverted papilloma and epithelial or mesenchymal tumors. Differentiation is very important as their lines of management are significantly different. Extensive vascular proliferation, atypical stromal cells and amorphous eosinophilic material on histopathology are typical of these polyps. A 11-year-old-girl presented to us with an extensive ANP masquerading as a malignant nasal mass, both clinically and radiologically. Patient underwent complete excision with functional endoscopic sinus surgery and is asymptomatic on regular follow-up. Prognosis is good and recurrence is very rare, if treated correctly. Only a few studies have been done on this topic, the literature is scant and awareness of this pathology is important.

Introduction

Inflammatory sinonasal polyps are classified into five types: edematous, glandular, fibrous, cystic and angiectatic nasal polyp (ANP). ANPs are considered to be a derivative of antrochoanal polyps commonly, but may be a variant of sinonasal polyps of any location. Their vascular supply is susceptible to compression at site of ostium, at the posterior choana and at the most dependent part within the nasopharynx [Citation1,Citation2]. Most ANPs arise in maxillary sinus and extend towards the choana and into the nasopharynx. Patients present with nasal obstruction and may have recurrent epistaxis. These polyps are benign, pseudo-neoplastic in nature. Imaging followed by complete excision is curative. They simulate malignancy due to their aggressive nature and features of bone erosion clinically or on imaging.

Case report

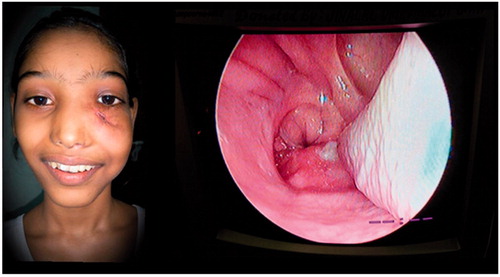

A 11-year-old female patient presented to our out-patient department with an exophytic mass over the left cheek, below the level of the medial canthus. It was completely obstructing the left nasal cavity and extending to the nasopharynx, oropharynx causing a bulge of the soft palate on the left side. The septum was pushed to the opposite side (Figure ).

Figure 1. ANP presenting as a large exophytic mass, left nasal polyp extending posteriorly into the oropharynx too. *Picture used after patient and relatives consent.

She had complaints of bilateral nasal obstruction with mouth breathing and occasional episodes of epistaxis. She noticed an exophytic mass over the left cheek under the medial canthus which progressively increased in size over 3 years. She had an associated intermittent headache and loss of smell but never had any visual complaints, she eventually developed a hyponasal voice.

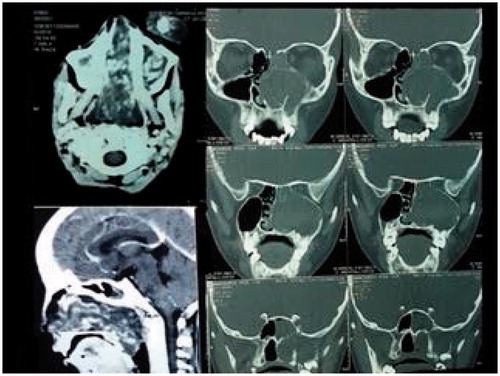

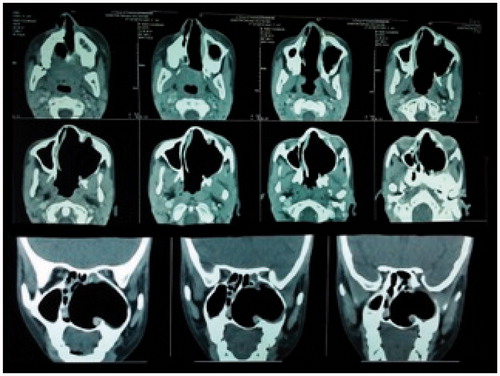

On clinical examination, an exophytic mass measuring 9 × 6×3.5 cm was present over the left cheek. It was firm, non-tender and did not bleed on touch. A pinkish nasal polyp was seen filling the left nasal cavity and extending into the nasopharynx and oropharynx producing a left soft palatal bulge. The polyp could be probed medially but not laterally. Visual acuity, pupillary reflexes and extra-ocular movements were completely normal. Cranial nerve examination was within normal limits. Radiologically, a contrast enhanced CT (CECT) scan showed a heterogeneously enhancing mass occupying the left nasal cavity and maxillary sinus, and opacification with some enhancement of the sphenoid, ethmoids and frontal sinuses was detected. There was destruction of anterior wall of the maxillary sinus and erosion of lamina papyracea with no intraorbital or intracranial involvement (Figure ). Based on these features, there was a suspicion of a malignant tumour.

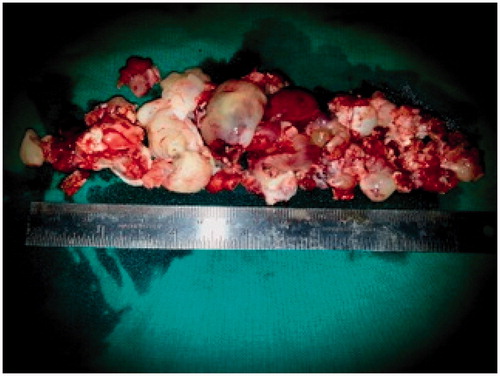

Patient was planned for surgery in a staged fashion under general anaesthesia. An informed consent was taken and excision biopsy of the external exophytic mass was done after clamping and ligating the pedicle below the left medial canthus (Figure ). The histopathology report was suggestive of a benign angiectatic polyp. In the second stage, a functional endoscopic sinus surgery was performed to clear the polypoidal mass from the left maxillary, ethmoidal sinuses, the left frontal and sphenoid sinuses (Figure ). The mass had to be removed in a piece-meal manner and was delivered partially through the oral cavity (Figure ). No vascular pedicle was particularly identified during surgery. All the sinus ostia were seen to be already widened due to bony remodelling. A 2 × 1 cm bony defect was identified in the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus leading to a breach in the skin over the left cheek which was sutured after freshening the skin margins (Figure ).

Figure 6. Suturing of the external skin defect and nasal packing over the balloon of Foley’s catheter.

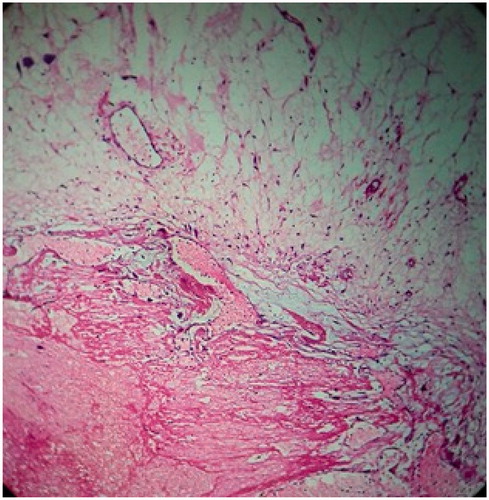

The polypoidal intranasal mass was sent for histopathology, which showed ectatic vessels, atypical stromal cells and amorphous eosinophilic material suggestive of benign ANP (Figure ). Anterior nasal packing was done with roller gauze and a Foley’s catheter was used to support the nasal packing (Figure ). After removal of nasal packing, patient developed a hypernasal voice (rhinolalia aperta) for which she had to undergo oral physiotherapy in the form of palatal exercises. This recovered over 2–3 weeks gradually. Rest of the post-operative period was uneventful. Patient is on regular follow-up and is asymptomatic since a year except for a small scar under the left medial canthus (Figures and ).

Discussion

The ANPs are uncommon pseudo-neoplastic lesions that can pose interesting pathophysiological questions and present a difficult diagnostic problem. They are also known as inflammatory granuloma telangiectaticum, vascular granuloma, pseudo-angioma and angiomatous/angiectatic polyp. However, the term angiectatic polyp reflects the fact that the lesion is not a real tumor and that it is clinically characterized by ectatic vessels with hemorrhage and chronic proliferation. They present clinically as soft, gelatinous translucent polypoidal, painless swelling with progressive obstruction of the nasal cavity associated with nasal discharge. Locally aggressive ANP may cause erosion, displacement of the adjacent bony structures, cheek swelling and proptosis. Diverse presentation with presence of bone destruction may simulate malignancy leading to a diagnostic dilemma. In a study of 31 cases of ANPs, the most common site of maxillary wall erosion was the medial wall (21/31), followed by the posterior lateral wall (3/31), upper wall (2/31), and septum (3/31). Of these, the nasal cavity and/or maxillary sinus were enlarged in 28 cases. None of the patients in this study were reported to have anterior maxillary sinus wall defect as observed in our patient [Citation3].

Vascular tumors are the most common non-epithelial tumors of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx [Citation4]. ANPs are difficult to differentiate from capillary or cavernous hemangioma, [Citation5] sometimes with organized or organizing hematoma [Citation6] and nasopharyngeal angiofibroma due to their predominant vascular component [Citation7]. Organized hematoma is usually sub-epithelial in location and characterized by admixture of fibrin network and hemorrhagic material with surrounding fibrous tissue margin, which prevents reabsorption of hematoma resulting in neovascularization and fibrosis. Cavernous hemangiomas have larger vascular luminae compared to those of angiectatic polyp. Sinonasal angiomas occur more often in the anterior nasal septum, the turbinate and vestibule. Both commonly present clinically with epistaxis, nasal obstruction and bleed significantly on biopsy. ANPs appear hypovascular or avascular on angiography due to their irregular racemose arrangement of dilated capillary-type vessels, in contrast to the normal arborizing pattern of vascularity in an angiofibroma. Specific locations of angiofibroma in pterygopalatine fossa with flow voids on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also helpful to differentiate between the two pathologies. Sometimes pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia of the surface epithelium of ANP may raise suspicion of squamous cell carcinoma which can be easily ruled out on histopathology. The differential diagnosis and their specific features have been described in .

Table 1. Differential diagnosis of angiectatic sinonasal polyps.

Though we had done a CECT for our patient, conventional MRI is a better modality for preoperative diagnosis of the ANP. It shows characteristic hypointensity on T1 weighted images and internal heterogeneous hyperintensity with a peripheral hypointense rim on T2 weighted images, as well as strong nodular and patchy enhancement on post-contrast MRIs [Citation5,Citation8]. Areas of mixed signal intensity on T2 weighted images are due to extensive areas of organized thrombus and necrosis in that part of polyp and the peripheral hypointense rim on T2 weighted images is due to old microhemorrhage with hemosiderin deposition on the surface of the polyp. Moreover, progressive enhancement on dynamic contrast enhancement (DCE) MRI is a very important diagnostic clue [Citation5]. Post-contrast strong enhancement of nasochoanal portion of ANP suggests extensive vascular proliferation and ectasis.

Many of the ANPs are diagnosed retrospectively on histopathology reporting (HPR). Biopsy in suspected cases is important as it can avoid radical treatment modality which may otherwise be given for some other differential. Characteristic features on HPR like extensive vascular proliferation, atypical stromal cells and amorphous eosinophilic material point towards ANP. Bizarre, large pleomorphic spindle cells in the stroma are part of the reactive secondary changes seen occasionally in sinonasal polyposis but are particularly prominent in ANPs [Citation9]. Although these extremely atypical mesenchymal cells can raise the suspicion of a soft tissue sarcoma, they should be considered in the context of the reactive changes they are associated with. In most of the reported cases, complete endoscopic excision was all that was required. In our case, the defect below the left medial canthus also needed to be repaired. Healing took place with a reasonable scar (Figure ). These patients tend to have a drastic change of voice postoperatively (rhinolalia aperta) which affects their quality of life. This needs to be addressed by detailed pre-operative counselling and post-operative rehabilitation by physiotherapy in the form of palatal exercises. In a paediatric case like ours, this can prove to be challenging. Simple techniques like blowing of a large balloon may help to a certain extent. Voice quality generally returns to normal within 3–4 weeks in most of the cases.

Conclusions

Angiectatic nasal polyps present in a myriad of ways, often simulating other pathologies including malignancy, hence distinguishing them correctly to avoid radical treatment for a benign pathology is of utmost importance.

Even in aggressive cases of ANP, correct imaging and complete excision by minimally invasive endoscopic technique is curative.

When one is dealing with such an extensive pathology in paediatric cases, detailed pre-operative counselling and post-operative rehabilitation form an integral part of management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Batsakis JG, Sneige N. Choanal and angiomatous polyps of the sinonasal tract. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:623–625.

- Sheahan P, Crotty PL, Hamilton S, et al. Infarcted angiomatous nasal polyps. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:225–230.

- Dai LB, Zhou SH, Ruan LX, et al. Correlation of computed tomography with pathological features in angiomatous nasal polyps. PLoS One. 2012;7:e53306.

- Fu YS, Perzin KH. Non-epithelial tumors of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and nasopharynx: a clinicopathologic study. I. General features and vascular tumors. Cancer. 1974;33:1275–1288.

- Wang YZ, Yang BT, Wang ZC, et al. MR evaluation of sinonasal angiomatous polyp. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:767–772.

- Kim EY, Kim HJ, Chung SK, et al. Sinonasal organized hematoma: CT and MR imaging findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1204–1208.

- Som PM, Cohen BA, Sacher M, et al. The angiomatous polyp and the angiofibroma: two different lesions. Radiology. 1982;144:329–334.

- De Vuysere S, Hermans R, Marchal G. Sinochoanal polyp and its variant, the angiomatous polyp: MRI findings. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:55–58.

- Nakayama M, Wenig BM, Heffner DK. Atypical stromal cells in inflammatory nasal polyps: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis in defining histogenesis. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:127–134.