Abstract

We report one case of sinus mucocele with vision loss hardly identified on CT, resulting in diagnosis delay. A 34-year-old man was referred to the department of ophthalmology in our hospital because of acute loss of his left vision since morning of the day. Left compressive optic neuropathy was suspected and CT was performed. However, CT did not clearly show its causative legion. The patient went home without receiving any therapy. After that, the patient’s vision was further damaged. MRI revealed the cystic lesion around the left anterior clinoid process which eroded left optic canal bone. Emergency surgery was performed, and both its cyst and optic nerve canal were opened endoscopically. After surgery, his left visual acuity was improved immediately. In conclusion, an MRI scan or the combination of CT and MRI modalities might be more useful for early and accurate diagnosis of paranasal sinus disease with visual disturbances.

1. Introduction

Paranasal sinus mucoceles adjacent to optical canal can cause compressive optic neuropathy [Citation1]. For prompt diagnosis and treatment, imaging is essential to identify the legions causing vision loss. However, currently, there is not a consensus which imaging modalities are best suited for the diagnosis of paranasal sinus disease with visual disturbances. Herein, we describe a case of sinus mucocele with vision loss whose causative lesion was hardly identified on a CT but clearly visible on MRI.

2. Case presentation

A 34-year-old man was referred to the department of ophthalmology in our hospital because of acute loss of his left vision since morning of the day. There was no history of trauma or prior sinus surgery. He had a similar episode of sudden vision impairment of his left eye about 3 years ago, which was milder and spontaneously recovered without receiving any treatment.

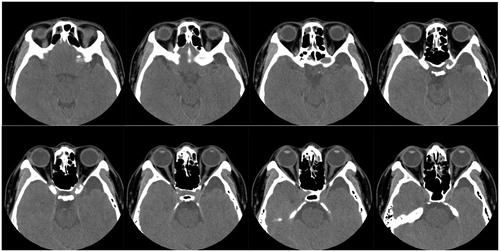

The patient had a visual acuity of counting fingers in the left eye. There were no abnormal findings in eye movements, slit-lamp and fundus examinations. Left optic neuropathy was one of the possible diagnoses. In order to detect the local compressive lesion nearby left optic nerve, CT without contrast of the paranasal sinuses was performed. Although CT showed scattered opacifications in bilateral sinuses (Lund-Mackey CT score of 3), it did not clearly show the causative legion (Figure ). CT revealed an arachnoid cyst in the middle cranial fossa and the patient consulted a neurosurgeon. But, this arachnoid cyst was not thought to be associated with the patient’s acute vision loss. The patient did not receive any curative treatments such as antibiotics or systemic steroid therapy and went home on that day.

Figure 1. Initial axial CT scans without contrast of paranasal sinus. Although CT showed mild mucosal swelling or partial opacifications in bilateral sinuses, it was hard to identify the causative legion of optic neuropathy.

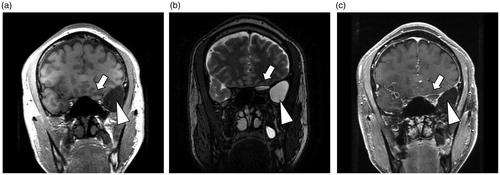

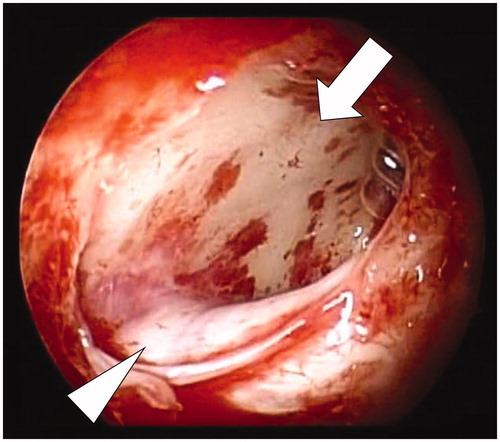

Two days later, again the patient visited our hospital since his left vision dropped further to as low as light perception. MRI with gadolinium contrast of paranasal sinuses was performed. MRI revealed a cystic lesion around left anterior clinoid process which was adjacent to the left optic canal (Figure ). The lesion was considered as sinus mucocele because it was T2-hyperintense, T1-isointense and gadolinium-contrast enhanced only its margin. Emergency endoscopic sinus surgery was performed by the otolaryngologists. Both the sinus cyst and left optic nerve canal were opened to avoid the risk of relapse (Figure ). The cyst was unilocular and lined with mucosa containing slight purulent content. The culture of mucocele content was positive for Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus capitis.

Figure 2. (a) T1-weighted, (b) T2-weighted and (c) Gd-enhanced coronal MRI images of paranasal sinus. MRI revealed a cystic lesion (arrow) around left anterior clinoid process which was adjacent to the left optic canal. There was an arachnoid cyst in the middle cranial fossa (arrowhead).

Figure 3. Intraoperative view of the cyst (arrow) and left optic nerve canal (arrowhead), both of which were opened endoscopically.

After surgery, the patient was treated with ceftriaxone and systemic steroid. His left visual acuity was improved immediately, up to 20/20 vision 5 days after surgery. There was no sign of recurrence of the sinus mucocele in 6 months after surgery.

3. Discussion

Paranasal sinus mucoceles with visual disturbances are treatable diseases only if optic nerves were decompressed promptly [Citation2]. Previous studies reported that the time to surgery and preoperative visual acuity could predict postoperative visual acuity improvement [Citation3,Citation4]. In the current case, we surmise that further delay of even short hours before surgery might be harmful to vision outcome since the patient’s vision was severely and rapidly deteriorated.

The diagnosis of sinus mucoceles is confirmed by imaging such as CT and MRI scans. For the evaluation of head and neck regions, CT is superior to MRI in the point of resolution, especially bone resolution. On the other hand, MRI is superior to CT in the point of better soft tissue contrast. Therefore, CT and MRI are complementary imaging methods [Citation5]. The combination and proper comparison of both modalities are important for accurate diagnosis of paranasal sinus diseases including tumor, infection, polyp and cyst.

In the present case, it was difficult to recognize the culprit lesion on initial axial CT which also showed a mild degree of ‘innocent’ sinusitis. One might mistake the cyst for mucosal swelling or sinusitis as observed for other portions of the sinuses. Moreover, the occurrence of mucoceles around orbital apex portion is very rare [Citation6,Citation7]. In contrast, MRI provided greater visibility of cystic lesion at first glance. Since, in our institution, CT without contrast was first-line imaging study for paranasal sinuses, we chose MRI for further investigation. MRI has its advantages in images with multiple sequences (T1, T2, etc.) and a smaller risk of adverse events associated with contrast enhancement (gadolinium in MRI vs. iodine in CT [Citation8]). We did not perform CT with contrast other than MRI with contrast in order to avoid an additional toxicity of iodinated contrast. CT with contrast, if done, may also have shown only margin enhancement of the sinus mucocele and may not have highlighted the subtle cystic abnormalities in the present case [Citation9]. We proposed that MRI should be eagerly performed when optic neuropathy due to paranasal diseases was strongly suspected but CT did not clearly indicate the causative lesions.

4. Conclusion

An MRI scan or the combination of CT and MRI modalities might be more effective for early detection and shortening time to surgery of sinus mucoceles with visual disturbances than examination based solely on a CT scan.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kenji Kondo (Department of Otolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Tokyo) for his valuable suggestions.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Devars Du Mayne M, Moya-Plana A, Malinvaud D. Sinus mucocele: natural history and long-term recurrence rate. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2012;129:125–130.

- Yumoto E, Hyodo M, Kawakita S, et al. Effect of sinus surgery on visual disturbance caused by spheno-ethmoid mucoceles. Am J Rhinol. 1997;11:337–343.

- Zukin LM, Hink EM, Liao S, et al. Endoscopic management of paranasal sinus mucoceles: meta-analysis of visual outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157:760–766.

- Morita S, Mizoguchi K, Iizuka K. Paranasal sinus mucoceles with visual disturbance. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37:708–712.

- Koeller KK. Radiologic features of sinonasal tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:1–12.

- Scangas GA, Gudis DA, Kennedy DW. The natural history and clinical characteristics of paranasal sinus mucoceles: a clinical review. Int Forum Aller Rhinol. 2013;3:712–717.

- Lim CC, Dillon WP, McDermott MW. Mucocele involving the anterior clinoid process: MR and CT findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:287–290.

- Beckett KR, Moriarity AK, Langer JM. Safe use of contrast media: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:1738–1750.

- Alshoabi S, Gameraddin M. Giant frontal mucocele presenting with displacement of the eye globe. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13:627–630.