Abstract

In acute vestibular syndrome (AVS), an infarct in the territory of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) can be mistaken for a peripheral vestibular lesion. We present a case that at first showed the clinical signs of a typical peripheral origin (uni-directional nystagmus, pathological head impulse test and no skew deviation), but performed the “bucket test” non-coherent with a peripheral AVS. CT and CT-angiography failed to identify the infarction in the AICA territory that was revealed on MRI the following day. In this case the “bucket test” was the determining factor that prompted the MRI. Besides that the test might be considered in all patients presenting with AVS, it has also the great advantage of being extremely cheap to produce.

Introduction

Acute vertigo in an emergency setting can sometimes be challenging to diagnose correctly, especially when trying to differentiate central from peripheral acute vestibular syndrome (AVS). As anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) strokes may mimic the symptoms and signs of a peripheral vestibular lesion, they are often missed early on [Citation1].

HINTS is an acronym consisting of Head Impulse test, Nystagmus and Test of Skew. HINTS has been suggested to be more sensitive than MRI-DWI in distinguishing central from peripheral AVS, and far more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that an acute MRI within the first 48 h cannot exclude a central lesion [Citation1].

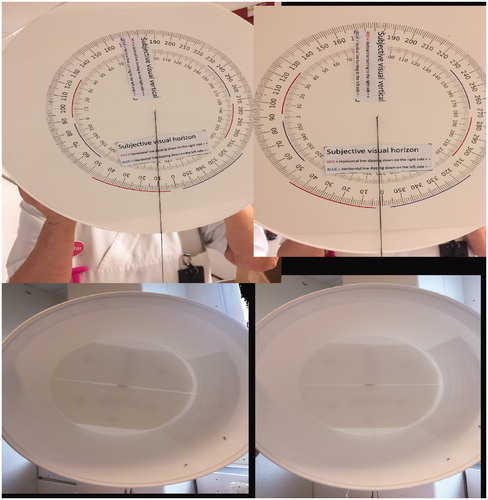

In an AVS of peripheral origin the utricle, supplied by the superior vestibular nerve, may be affected. It is well established that damage to the utricle causes a subjective tilt in the frontal plane. The bucket test represents a method to indirectly test the utricular function of an individual. [Citation2] (See ).

Case report

Our case concerns a 70 years old woman, previously diagnosed with hypothyroidism. This disease was of no consequence to her everyday life.

One morning at 2 am, while going to the bathroom, she noticed acute oncoming vertigo and vomited several times. She went back to bed hoping that these events would subside with a couple more hours of sleep. However, she woke up with nausea and vertigo, strongly related to active motion, prompting her to visit the emergency department.

At the first examination, the patient presented a positive head impulse test to the right side, a 3rd degree nystagmus with the fast phase beating to the left and no skew deviation. She complained at that moment of no other neurological symptoms and had no other pathological findings. A CT-scan of the brain was performed showing nothing pathological. The ENT-doctor on call received the patient with the request to treat the patient’s peripheral acute vestibular syndrome according to local guidelines. The ENT doctor noticed that the patient had spontaneous, asynchronous blinking that was out of step. The patient also had difficulties following commands, for example the instruction to look to the left. As a final test before admitting the patient to the ENT-ward, the doctor performed “The Bucket Test”. When performing the test, the patient did not only perceive the line used for testing subjective visual horizontal/vertical (SVH/SVV) as two lines (subtle diplopia), but also tilted the line 2–4 degree to the left which is to the wrong side if a right-sided peripheral AVS is suspected.

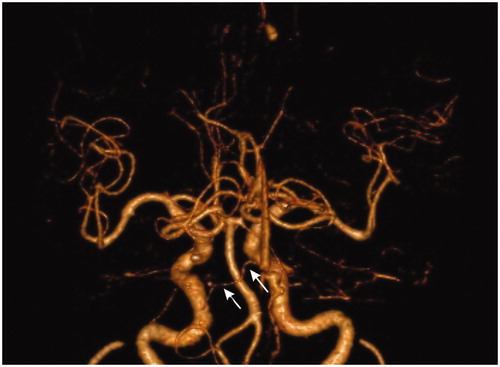

Because of these new clinical signs a neurological consultation was requested, coming to agreement with the ENT-doctor that a cerebellar lesion could not be ruled out. A CT angiography of the posterior cerebellar circulation was performed, again showing nothing pathological. The patient was then admitted to the neurological ward for observation.

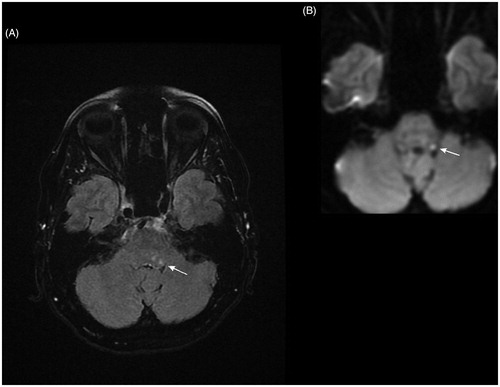

The next morning a diffusion weighted MRI was performed showing an approximately 3 mm infarction in the area involving left facial colliculus and the area of left abducens nucleus, structures that are supplied by the left AICA. (See and ). This findings explain the patient’s vertigo, the spontaneous, asynchronous blinking out of step and the difficulties the patient had to look to the left. As the infarction progressed the patient also developed a small diplopia.

Although the patient was cared for by another clinic, we know that the patient received antiplatelet stroke treatment, improved and suffered no apparent sequelae.

Discussion

Our case showed no central HINTS (i.e. had a unidirectional nystagmus, a pathological head impulse test, and no skew deviation), which suggests a peripheral AVS. The only non-coherent clinical sign was a tilt of SVH/SVV to the wrong side [Citation3], meaning that in this case the patient tilted the bucket to the left, in the direction of the nystagmus, and not to the right as would have been the case in a right-sided peripheral AVS. Tilting of SVH/SVV towards the side of a peripheral lesion suggests that the superior vestibular nerve, and thereby the utricle, is affected [Citation4]. It is, however, not an obligate finding since in vestibular neuritis, the actual dysfunction of the vestibular system is often incomplete and the bucket test might be normal in a peripheral AVS [Citation5]. If, however, the test shows non-coherent results with a peripheral AVS, then a central lesion should be suspected, even if, as in the present case, the SVH/SVV outcome was small.

AICA strokes represent roughly 1% of all cerebral strokes [Citation6] and since they may mimic the symptoms and signs of a peripheral lesion, they are often missed early on. MRI in the emergency setting is not as available as one might wish for. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that an acute MRI within the first 48 h cannot exclude central lesions. The clinician has to rely on the “HINTS” paradigm and although it is well known that a CT-scan does not find all lesions, most physicians persist in ordering a scan when encountering a dizzy patient. At our hospital, most often an additional CT angiography is performed, presumably to examine the patency of the posterior circulation of the brain. In this case both scans failed to identify the lesion. This case shows that the bucket test is a quick and cost-efficient examination tool that is helpful in the differentiation between peripheral and central AVS.

Conclusions

AICA infarcts can early on be mistaken for an acute vestibular syndrome of peripheral origin. Sometimes HINTS and CT are not enough to rule out a cerebellar lesion. Bedside SVH/SVV, “the bucket test”, is a very quick and cost-efficient clinical tool that can be of help in the emergency setting to differentiate between peripheral and central acute vestibular syndromes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, et al. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40:3504–3510.

- Zwergal A, Rettinger N, Frenzel C, et al. A bucket of static vestibular function. Neurology. 2009;72:1689–1692.

- Dieterich M, Brandt T. Ocular torsion and tilt of subjective visual vertical are sensitive brainstem signs. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:292–299.

- Böhmer A, Rickenmann J. The subjective visual vertical as a clinical parameter of vestibular function in peripheral vestibular diseases. J Vestib Res. 1995;5:35–45.

- Taylor RL, McGarvie LA, Reid N, et al. Vestibular neuritis affects both superior and inferior vestibular nerves. Neurology. 2016;87:1704–1712.

- Roquer J, Lorenzo JL, Pou A. The anterior inferior cerebellar artery infarcts: a clinical‐magnetic resonance imaging study. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998. 97(4):225–230.