Abstract

Vertebral artery (VA) injuries following trauma to the neck are uncommon. We treated a case of VA injury in an 82-year-old man presented to a hospital with penetrating neck injuries caused by broken glass and underwent surgery for retrieval of the pieces. After the surgery, he complained about hoarseness, computed tomography scan showed glass remnants in his neck, damaging the right VA and forming a pseudoaneurysm. Thereafter, he came to our hospital seeking treatment for the injured VA. Severe bleeding may have occurred during exploration around the pseudoaneurysm; hence, we performed interventional angiography and occluded the right VA, followed by neck surgery. Five days after embolization, we performed the surgery to remove the glasses. There was no bleeding during and after the operation, and the patient was discharged without any complication. In this case report, we discuss the management of VA injury and review the relevant medical literature.

Introduction

Vertebral artery (VA) injuries following trauma to the neck are uncommon. These injuries are almost always related to penetrating neck injuries following gunshot, stab wounds, or iatrogenic reasons [Citation1,Citation2]. The management of patients with VA injuries has been controversial; however, recently, endovascular management of VA injuries has been preferred owing to difficulties in the surgical management of VA [Citation3]. We treated a case of VA injury in an 82-year-old man caused by glass remnants in his neck. In this report, we discuss the management of these injuries and review relevant medical literature.

Case report

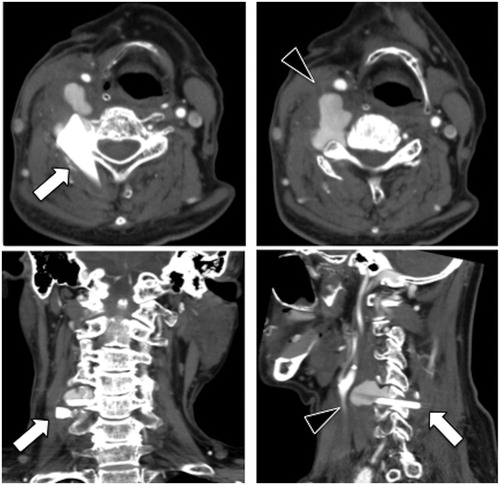

An 82-year-old man presented with penetrating neck injuries to a hospital 11 days previously after a fall and broken glass penetrating his neck. When he arrived at the hospital with massive bleeding from his neck, an emergent surgery was performed to control the bleeding. On exploration, some glass pieces and an injured right internal jugular vein were detected. The glass pieces were removed, and the right internal jugular vein was repaired. His postoperative condition was good, and he was prepared for discharge. However, the day before discharge, he complained about hoarseness. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (ceCT) scan, performed for the first time since admission (Figure ), revealed two triangular remnant pieces of glass in his neck, one of which was located between the right transverse process of C4 and C5. The glass damaged the right VA. He presented to our hospital for surgical removal of the remnants and treatment of the injured VA.

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing remnants of glass pieces in the neck (arrow) and the damaged right vertebral artery and pseudoaneurysm (arrow head).

Upon arrival, his vital signs were stable. Physical examination revealed a lateral scar on his right neck, vocal cord paralysis, and Horner symptom on the right side, but no neck swelling, flush, or other neurological symptoms were noted. The ceCT scan from the first hospital revealed that the glass had damaged the right VA and a pseudoaneurysm was formed, with no abscess or inflammation. Although the vital signs were stable, severe bleeding may have occurred during exploration around the VA pseudoaneurysm. Hence, diagnostic and therapeutic angiograms for VA were considered necessary before the neck surgery.

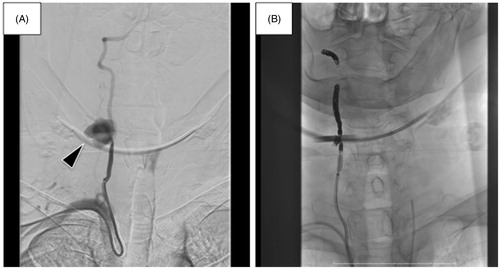

The diagnostic angiogram demonstrated right VA pseudoaneurysm at the level of C4-5 vertebral body (Figure ). The right VA was dominant, but the left VA was well developed, and balloon occlusion test was performed on the right VA. Ischemic tolerance to the right VA occlusion was confirmed. Thus, a neurosurgeon performed artery occlusion at the proximal and distal portions of the VA pseudoaneurysm with detachable coils and vascular plug (Figure ).

Figure 2. (A) The vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm (arrow head). (B) Successful obstruction of the right vertebral artery using coil embolization.

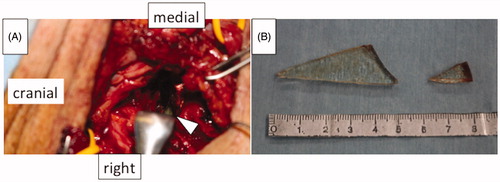

Five days after embolization, we performed the neck surgery. We opened the wound and detected numerous granulomatous tissues around the right carotid sheath. We incised the right sternocleidomastoid muscle to obtain a better operating field. The carotid and jugular systems were explored, and the repaired internal jugular vein was detected. No damage was found to the carotid artery or vagal nerve. We dissected the granulomatous tissue on the lateral side of the carotid sheath by pulling the carotid sheath medially. A hematoma was detected on the right of the C4-5 vertebral body, and the right sympathetic trunk was apparently transected. We found the larger glass piece piercing between the C4 and C5 transverse processes (Figure ) and carefully pulled it off without any bleeding. The smaller piece was detected on the lateral side of the larger piece and was removed without damaging the adjacent organs (Figure ). There was no bleeding after the operation, and the patient enjoyed his daily meal without dysphagia, although the right vocal cord paralysis was not recovered within the observation period. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 5.

Discussion

VA injuries do not frequently occur because of its location within the spine. These injuries comprise less than 1% of all vascular injuries [Citation4] and can result in free hemorrhage pseudoaneurysm formation, arterio-venous fistulae, occlusion, dissection, or intimal injury of the artery. Intimal injury is usually the result of blunt VA injury, resulting in partial thrombosis of the artery. AVFs of the VA are rare and usually occur between the vertebral artery and vertebral veins; however, the internal jugular vein may also get affected [Citation5]. Pseudoaneurysms are fairly common. Untreated, the mortality rate of VA pseudoaneurysm may be as high as 70% [Citation6].

The VA is usually the first cephalic branch of the subclavian artery and is divided into four parts: V1; from the origin of the vertebral artery to the point at which it enters the C6 transverse process, V2; the segment within the cervical transverse processes from C6 to C2, V3; the extra-cranial segment between the transverse process of C2 and the base of the skull, as it enters the foramen magnum, V4; the intra-cranial portion terminating at the formation of the basilar artery [Citation7].

The management of patients with VA injury has been controversial. However, recently, endovascular management of VA injuries has been preferred because of the difficulties in the surgical management of VA [Citation3]. V1 usually presents fewer challenges to the surgeon as it is readily exposed in the neck [Citation8]. V2 is extremely difficult to expose, especially with active bleeding, as these parts of the artery are completely concealed within the bony tunnel formed by the foramina transversaria. V3 is situated in the deep and unfamiliar sub-occipital triangle [Citation9]. Head and neck surgeons do not deal with V4; intervention angiography or surgery by a neurosurgeon should be considered. Because of these difficulties, surgery is not always the best option. Thus, endovascular management is a good option.

The anatomy of the vertebrobasilar artery system is such that paired VAs supply the basilar artery. In the event that one is injured, the contralateral artery can compensate. There is also significant collateralization potential through the Circle of Willis. Hence, the risk of occluding the VA in the presence of a normal contralateral vessel is small [Citation7]. Thus, if patients are hemodynamically stable, and the VA on the unaffected side shows normal findings on imaging, non-invasive treatment using embolism by angiogram can be attempted in most cases [Citation7,Citation10].

On the contrary, if the opposite side is underdeveloped, the embolism can cause complications, such as fatal infarction in the midbrain and cerebellum [Citation11]. Hence, in that case, surgical repair of the blood vessel was preferred [Citation11]. However, Khoie et al. [Citation12] and Dolati et al. [Citation13] reported cases of a traumatic VA pseudoaneurysm treated successfully using an endovascular stent graft to preserve the VA. Dolati et al. reported that pseudoaneurysm rupture remains a potential complication in the early post-procedural period [Citation13]; hence, in case there is no massive bleeding and patients are hemodynamically stable, using an endovascular stent graft is a very good choice.

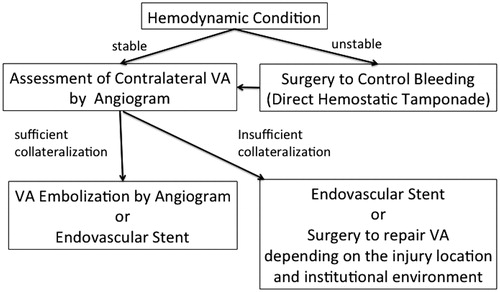

If there is massive bleeding and patients are hemodynamically unstable, there is no definite consensus of management. Stopping the bleeding is required as soon as possible, but occluding the VA without confirming the presence of a normal contralateral vessel can cause fatal complications. Hence, direct hemostatic tamponade should be conducting by using hemostatic agents or gauze compression. The anesthesiologist should be informed of the need for fluid resuscitation to maintain perfusion pressure to reduce the risk of posterior circulation ischemia [Citation14]. After the bleeding has been controlled, intraoperative angiography should be performed. According to the results of the angiography and whether the injured VA can be observed in the operating field, the surgeon should choose the treatment method. Ligation of VA or embolism by angiogram can be performed in the presence of a normal contralateral vessel. Primary repair of VA or endovascular stent graft should be chosen in the absence of a normal contralateral vessel. Hence, treatment for VA injuries can be determined by the hemodynamic condition of the patient and the condition of the contralateral VA. Figure presents the available treatment modalities.

In this patient, remnants of glass pieces remained in the neck; hence, surgery was needed to remove them. However, even the careless removal of the remnants could cause massive bleeding from the VA pseudoaneurysm. The hemodynamic condition of the patient was stable, and the VA on the unaffected side showed normal findings on imaging. Hence, we concluded that non-invasive treatment using embolism by angiogram followed by the neck surgery was the best choice of management.

Conclusion

Injury to the VA following penetrating trauma is rare. Treatment of VA injuries is based on the hemodynamic condition of the patient and the condition of the contralateral VA. Surgery is not always the best option because interventional angiography techniques have been revolutionized recently. The decision for the treatment method must consider the best option in each case.

Ethical approval

The patient provided informed consent.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are response for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Yilmaz MB, Donmez H, Tonge M, et al. Vertebrojugular arteriovenous fistula and pseudoaneurysm formation due to penetrating vertebral artery injury: case report and review of the literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2015;25:141–145.

- Nason RW, Assuras GN, Gray PR, et al. Penetrating neck injuries: analysis of experience from a Canadian trauma centre. Can J Surg. 2001;44:122–126.

- Gok M, Aydin E, Guneyli S, et al. Iatrogenic vascular injuries due to spinal surgeries: endovascular perspective. Turk Neurosurg. 2018;28:469–473.

- Meier DE, Brink BE, Fry WJ. Vertebral artery trauma: acute recognition and treatment. Arch Surg. 1981;116:236–239.

- Kypson AP, Wentzensen N, Georgiade GS, et al. Traumatic vertebrojugular arteriovenous fistula: case report. J Trauma. 2000;49:1141–1143.

- Wiener I, Flye MW. Traumatic false aneurysm of the vertebral artery. J Trauma. 1984;24:346–349.

- Mwipatayi BP, Jeffery P, Beningfield SJ, et al. Management of extra-cranial vertebral artery injuries. Eur J Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2004;27:157–162.

- Hatzitheofilou C, Demetriades D, Melissas J, et al. Surgical approaches to vertebral artery injuries. Br J Surg. 1988;75:234–237.

- Berguer R. Suboccipital approach to the distal vertebral artery. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:344–349.

- Mittendorf E, Marks JM, Berk T, et al. Anomalous vertebral artery anatomy and the consequences of penetrating vascular injuries. J Trauma. 1998;44:548–551.

- Park JJ, Shim HS, Jeong JH, et al. A case of cerebellar infarction caused by vertebral artery injury from a stab wound to the neck. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:431–434.

- Khoie B, Kuhls DA, Agrawal R, et al. Penetrating vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm: a novel endovascular stent graft treatment with artery preservation. J Trauma. 2009;67:E78–E81.

- Dolati P, Eichberg DG, Thomas A, et al. Application of Pipeline Embolization Device for Iatrogenic Pseudoaneurysms of the extracranial Vertebral Artery: A Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literarure. Cureus. 2015;7:e356.

- Peng CW, Chou PT, Bendo JA, et al. Vertebral artery injury in cervical spine surgery: anatomical considerations, management, and preventive measures. Spine J. 2009;9:70–76.