Abstract

First branchial cleft anomalies are uncommon. They may present as cysts, sinuses or fistulae and can occur anywhere along the course of the first branchial arch tract. The current classification system is based on both histological and clinical features. Surgical excision with monitoring of the facial nerve is the accepted treatment of choice. We present a case of a 2-year old with a duplication of the external auditory canal, based on a first branchial cleft anomaly. Based on clinical presentation this case is classified as first branchial cleft sinus Work Type 1 with ectodermal and mesodermal derivatives. Marsupialization through the cartilaginous external auditory canal proved to be an effective and minimally invasive treatment.

Introduction

The branchial arches are the embryological precursors of the head, neck and pharynx. Anomalies of the branchial arches are the second most common type of congenital neck mass, after thyroglossal duct cyst [Citation1–3]. Second branchial arch anomalies are the most common and account for approximately 95% of the cases [Citation1]. First branchial cleft anomalies (FBCA) are less common: they account for <8% of all branchial anomalies [Citation4–6]. The annual incidence is largely unknown and has been cited as 1 per 1,000,000 [Citation7]. Because first branchial cleft anomalies are uncommon, recognizing them can be difficult and they are often misdiagnosed [Citation8]. They may present as cysts, sinuses or fistulae and can occur anywhere along the course of the first branchial arch tract, distributed in the lateral neck below the external auditory canal, above the hyoid bone, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and posterior to the submandibular angle [Citation4,Citation6]. In 1972 Work proposed a classification system for first branchial cleft anomalies based on histological and clinical features [Citation9]. Type 1 anomalies are of ectodermal origin and are considered a duplication of the membranous external auditory canal. Type 2 anomalies are of ectodermal and mesodermal origin and are considered a duplication of the membranous and cartilaginous external auditory canal [Citation9]. The usefulness of this classification system has been debated [Citation10]. Surgical excision with monitoring of the facial nerve is generally accepted to be the treatment of choice in first branchial cleft anomalies [Citation5,Citation8].

Case presentation

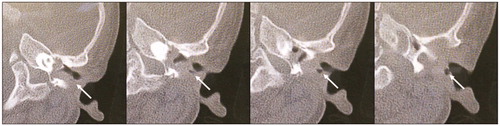

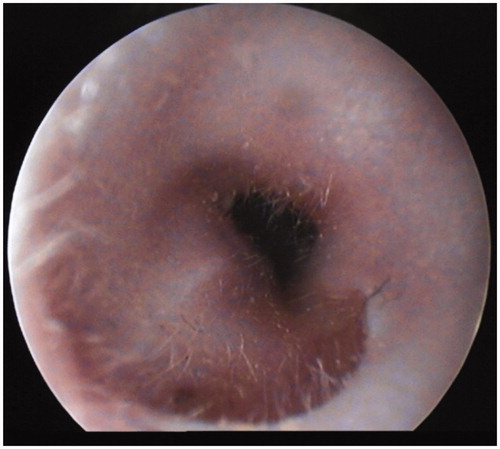

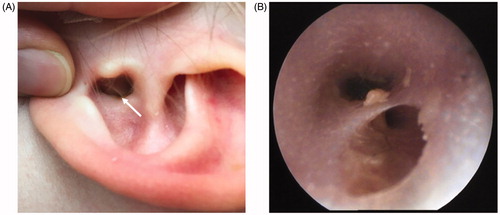

A 2-year-old girl reported to the hospital with recurrent infections of an extra orifice in the left external auditory meatus. On clinical examination, a sinus of the cartilaginous external auditory canal was seen (Figure ). There were no other anatomical deformities of the external ear. Otoscopic examination showed that the tympanic membrane was intact and had a normal anatomy. A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a sinus originating from the cartilaginous external auditory canal (Figure ). The sinus tract ended superficially, travelling adjacent to the external acoustic canal and not extending deeply in the parotid gland or facial nerve. The sinus had a blind ending (cul-de-sac) laterally to the tympanic membrane. The tympanic membrane and the auditory ossicles of the first pharyngeal arch (i.e. malleus and incus) were present. There was no malformation of the Eustachian tube or other middle ear structures. A concurrent bilateral serous otitis media was seen. Audiometry was performed and showed a conductive hearing loss fitting with a bilateral otitis media. Surgery was planned; because of the aforementioned clinical findings an uncommon surgical approach was chosen. A less invasive marsupialization technique was performed as opposed to the commonly performed excision, primarily because of the favorable position of the anomaly next to the external auditory canal, not extending deeply in the parotid gland or facial nerve. Prior to marsupialization the end of the sinus was verified using a sinus probe. The sinus seemed to consist of both skin and cartilage. The sinus was marsupialized making a lengthwise incision of the cartilaginous external auditory canal. Bilateral ventilation tubes were inserted. The surgery was performed using NIM® nerve monitoring of the facial nerve. On follow-up three months after surgery, the external auditory canal was healed and there was no sign of recurrence of the sinus (Figure ). The patient did not have complaints of recurrent infections, there were no complications and the patient made an uneventful recovery. Audiometry (otoacoustic emission) was performed and showed bilateral normal hearing.

Figure 1. Preoperative images. (A) Preoperative picture, the with arrow points at the sinus of the cartilaginous auditory canal. (B) Preoperative otoscopic image.

Discussion

Classification of first branchial cleft anomalies

First branchial cleft anomalies result from a subtotal closure of the ectodermal part of the first branchial cleft. They may present as a cysts, sinuses or fistulae, depending on the degree of closure [Citation8,Citation11]. They have been classified by Work in two groups based on histological and clinical features [Citation9]. Type 1 anomalies are of ectodermal origin. Characteristically, these lesions occur medial to the concha. They lie superficial to the facial nerve and extend parallel to the normal external auditory canal. They terminate in a cul-de-sac near the osseous-cartilaginous intersection of the external auditory canal at the level of the mesotympanum. They usually present as a cyst; a sinus develops after rupture or secondary infection [Citation8,Citation9]. Type 2 anomalies are of ectodermal and mesodermal origin; containing both skin and cartilage. Characteristically, a sinus passes from an external opening cranial in the neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, medial or lateral to the facial nerve and closely related to the parotid gland. The sinus ends either blindly or open in the cartilaginous external auditory canal [Citation9,Citation11]. In both types the middle ear cavity and the tympanic membrane are intact. Type 1 first branchial cleft anomalies are very rare, while Type 2 first branchial cleft anomalies are more frequent [Citation12].

Based on the clinical presentation of the first branchial cleft anomaly in this case report it would be classified as a Work Type 1 first branchial cleft anomaly. The sinus was superficial to the facial nerve and had no close relation to the parotid gland or the facial nerve. Furthermore, the sinus was parallel to the normal external auditory canal and it ended in a cul-de-sac lateral to the tympanic membrane at the level of the mesotympanum. There was no histological examination performed, because the sinus was not excised but marsupialized. However, during surgery the sinus seemed to consist of both skin and cartilage. This would indicate that based on histological examination this case would probably be a Work Type 2 first branchial cleft anomaly.

In a case series by Belenky et al. in 1980 it was already confirmed that the usefulness of the various classifications of first branchial cleft anomalies is limited, and it is complicated to correlate histological criteria with clinical presentation. They conclude that both Work Type 1 and Work Type 2 anomalies can have ectodermal and mesodermal derivatives [Citation10]. Probably of more clinical significance is the classification system presented by Olsen et al. in 1980. Their classification system is derived from the classification system of the second branchial arch anomalies in cysts, sinuses and fistulae [Citation4]. Cysts are buried remnants of the branchial arch without an opening. A sinus is a blind ending tract and may connect with either the skin (branchial cleft anomaly), or the pharynx (branchial pouch anomaly). A fistula is a communication between two epithelialized surfaces, and requires communication between the branchial cleft and pouch [Citation1,Citation4].

Treatment of first branchial cleft anomalies

Surgical excision with facial nerve monitoring is the definitive treatment for first branchial cleft anomalies [Citation3,Citation6]. Work et al. propose surgical excision, consisting of parotid gland and facial nerve dissections. After the lesion is excised, in order to marsupialize this area of recurrence, the membranous external auditory canal is incised lengthwise [Citation9]. In a flow chart by Shinn et al. in 2015 it was proposed Work Type 1 anomalies usually only require surgical excision of the tract superficial to the facial nerve, while Work Type 2 anomalies require a parotidectomy. Both anomalies require otologic surgery if there is involvement of the middle ear [Citation3]. In this case report the surgeon decided to only use the marsupializaton technique, making a lengthwise incision in the cartilaginous external auditory canal. The decision for this minimally invasive approach was made, because on otoscopic- and CT-imaging the sinus tract travelled adjacent to the external acoustic canal and did not extend deeply in the parotid gland or facial nerve. On the basis of clinical examination, we estimated the chances of future problems such as recurrence of the anomaly and recurrent infections as very low, making marsupialization an appropriate and safe technique. On follow-up there were no recurrent infections and the external auditory canal was healed. This minimally invasive approach proved to be an effective treatment for anomalies that lie superficial to the facial nerve and do not extend into the parotid gland.

Conclusion

First branchial cleft anomalies account for less than 8% of all branchial arch defects. They can have close involvement with the external auditory canal, the facial nerve and the parotid gland and are typically located in the peri-auricular area. Recognizing them can be difficult and they are often misdiagnosed. The current classification system by Work with both histological and clinical criteria has proved to be confusing. We propose to use the classification system by Olsen combined with the classification by Work for clinical presentation. The histological classification can be divided in ectodermal, mesodermal and endodermal derivatives. The case presented in this case report would be classified as a first branchial cleft sinus Work Type 1 with both ectodermal and mesodermal derivatives. Marsupialization through the cartilaginous external auditory canal proved to be an effective treatment. We propose adopting this minimally invasive technique as the treatment of choice in first branchial cleft anomalies without close involvement of the facial nerve, parotid gland and middle ear.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, et al. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights Imaging. 2016;7(1):69–76.

- Al-Khateeb T, Al Zoubi F. Congenital neck masses: a descriptive retrospective study of 252 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2242–2247.

- Shinn JR, Purcell PL, Horn DL, et al. First branchial cleft anomalies: otologic manifestations and treatment outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(3):506–512.

- Olsen K, Maragos N, Weiland L. First branchial cleft anomalies. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(3):423–436.

- D′Souza AR, Uppal HS, De R, et al. Updating concepts of first branchial cleft defects: a literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;62(2):103–109.

- Quintanilla-Dieck L, Virgin F, Wootten C, et al. Surgical approaches to first branchial cleft anomaly excision: a case series. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2016;2016:3902974.

- Maithani T, Pandey A, Dey D, et al. First branchial cleft anomaly: clinical insight into its relevance in otolaryngology with pediatric considerations. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66(S1):271–276.

- Triglia J-M, Nicollas R, Ducroz V, et al. First branchial cleft anomalies. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(3):291.

- Work WP. Newer concepts of first branchial cleft defects. Laryngoscope. 1972;82:1581–1593.

- Belenky W, Medina J. First branchial celft anomalies. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(1):28–39.

- Ford GR, Balakrishnan A, Evans JNG, et al. Branchial cleft and pouch anomalies. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(2):137–143.

- Bajaj Y, Ifeacho S, Tweedie D, et al. Branchial anomalies in children. J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(8):1020–1023.