Abstract

Parapharyngeal space (PPS) tumors are a rare entity and account for less than 1% of all head and neck tumors. Although they exhibit a benign behavior, malignant neoplasms may arise from any of the structure contained in the space. Differential diagnosis of a PPS mass can be determined based on its origin from the prestyloid or poststyloid space. Furthermore, the choice of surgical approach is dictated by the size of the tumor, its location, its relationship to the great vessels, and suspicion of malignancy. Chordomas are rare, slow-growing tumors arising from remnants of the notochord. They are locally aggressive malignant neoplasms. The majority of head and neck chordomas arise in the skull base with a small minority arising along the cervical spine. In this report, we describe the first case of a patient with a chondroid chordoma of the PPS with no direct involvement of the axial skeleton.

Introduction

Parapharyngeal space (PPS) tumors account for less than 1% of all head and neck tumors and mostly exhibit a benign behavior. They include tumors arising primarily in the PPS, extending to the PPS from adjacent structures or metastatic tumors from distant malignancies [Citation1]. More than 80% of PPS tumors were found to be benign and less than 20% were found to be malignant [Citation2]. The routine use of Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) along with other techniques such as arteriography and magnetic resonance angiography which are performed in selected cases are extremely relevant for the correct diagnosis and workup of these patients. Pre-operative biopsies and fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) studies have also been suggested [Citation1].

The PPS is shaped like an inverted pyramid extending from the skull base to the greater horn of the hyoid bone. It is bounded by the pharynx medially and anteriorly, the ramus of the mandible laterally, and the prevertebral fascia posteriorly. It is divided by the styloid diaphragm into the pre-styloid space which contains part of the deep lobe of the parotid, fat, and some minor salivary glands; and the post-styloid space which includes the internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, the lower cranial nerves, and sympathetic chain [Citation1].

Patients with PPS tumors may be asymptomatic at presentation or they may present with otologic symptoms related to eustachian tube dysfunction, obstructive symptoms such as dysphagia, dysarthria, nasal obstruction, snoring, sleep apnea and even exertional dyspnea [Citation3]. Some even present with syncope, but this usually indicates a malignant process and sometimes even a recurrence in patients with head and neck malignancy [Citation4,Citation5].

The PPS can also be the site of origin of very rare tumors including leiomyosarcomas [Citation6], mesenchymal chondrosarcoma [Citation7] and ganglioneuromas [Citation8]. This report mentions the first case of parapharyngeal chondroid chordoma.

Case report

A 19 years old female with no previous medical illnesses, presented to the ENT clinic with history of nasal obstruction, mouth breathing and sleep disturbance. Examination of the oral cavity and oropharynx revealed a parapharyngeal mass pushing the left tonsil medially with more than 75% obstruction of the oropharynx. Fiberoptic nasal scope showed a patent nasal cavity bilaterally. A mass was encountered at the level of the nasopharynx covered with normal-appearing mucosa and showing no signs of ulceration or discharge.

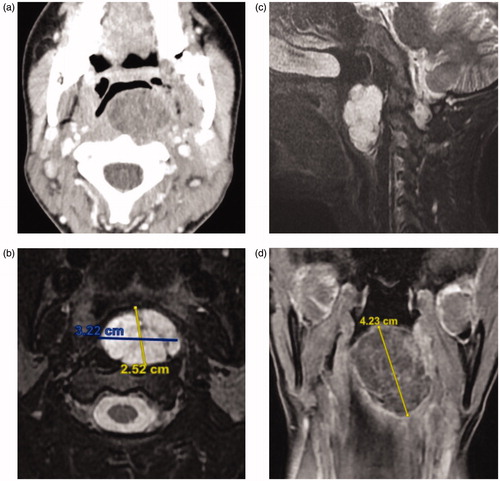

Contrasted CT scan of the head and neck revealed a well-defined non-enhancing cystic left pharyngeal mucosal space lesion with no bone erosion to the surrounding structures (Figure ).

Figure 1. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the neck shows a large well-circumscribed left retropharyngeal mass lesion protruding into the oropharynx. The lesion is remodeling the adjacent vertebral body, without bony erosion or intraspinal extension. (b, c) Axial and sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the neck demonstrate a heterogeneously hyperintense mass with low signal intensity internal septations. The overlying pharyngeal mucosa is intact and no cervical lymphadenopathy is seen. (d) Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI shows peripheral enhancement of the left retropharyngeal mass, as well as enhancement of the internal septations.

Contrasted MRI neck showed a multi-septated cystic mass causing mass effect on the prevertebral muscles at C1–C2 level, with intact pharyngeal mucosa. The mass showed a high signal intensity on T2, low signal intensity on T1 with an enhancing capsule (Figure ).

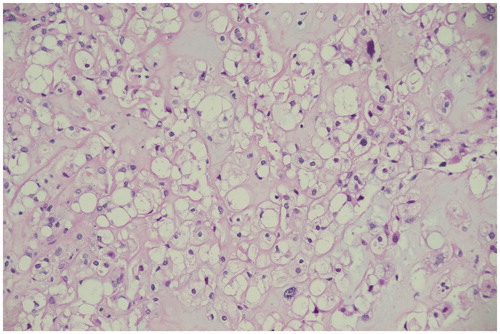

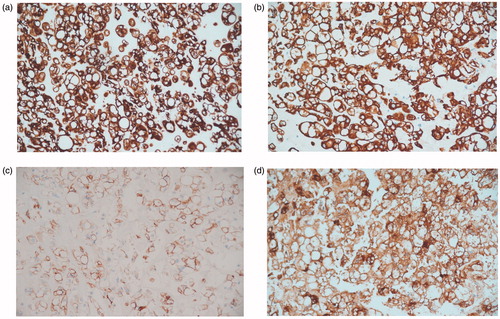

Surgical planning included discussion with the anesthetist about the approach to the airway and the surgical consent included transcervical approach with possible mandibulotomy and standby tracheostomy. The patient underwent left trans-cervical excision of the parapharyngeal mass alone. Intraoperatively the mass was found to be adherent to the prevertebral fascia, however, no bony involvement was noted. Pharyngeal wall injury was encountered during dissection of the tumor and primary repair was done followed by insertion of a nasogastric tube. The tumor was removed in whole and measured 4 cm in the longest diameter. Postoperatively, the patient remained on NGT feeding for a week and afterwards was evaluated with a barium swallow which showed no leak. NGT was then removed and the patient was discharged. On her follow-up, she was doing well. Her symptoms improved and feeding was back to normal. Her final pathology showed a chondroid chordoma. Microscopically the tumor showed lobulated architecture formed of cords and nest of vacuolated clear cell sit within chondromyxoid stroma (Figures and ).

Figure 2. Light microscopy photograph of the tumor shows cords and lobules of vacuolated cells separated by fibrous septa with chondromyxoid stroma (Hematoxylin and eosin stain; ×100 and ×200).

Figure 3 Light microscopy photographs of immunohistochemistry staining study of the tumor cells show (a) cell membrane positivity to CK CAM 5.2, (b) cell membrane positivity to CK 19, (c) cell membrane positivity to EMA and (d) cell membrane positivity to S100. (All magnifications are ×200).

A multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board meeting was held, and the combined decision was for the patient to undergo radiotherapy. She is currently following in the head and neck clinic with no signs of recurrence.

Discussion

Chordomas are rare primary tumor of the bone that arise from the remnants of the embryonic notochord, along the midline craniovertebral axis, most commonly in clivus and sacrococcygeal regions. They are slow-growing and locally aggressive malignant neoplasms [Citation9]. The majority of head and neck chordomas arise in the skull base with a small minority arising along the cervical spine. Reports of extra-axial locations in the head and neck have found them arising in the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, lateral nasal wall, oropharynx, and the soft tissue of the neck [Citation10]. Cranial chondroid chordoma (CC), a subtype of chordoma, was first described by Falconer et al. [Citation11] in 1968 as a biphasic neoplasm consisting of cartilaginous and chordoid elements in variable proportions. In later years, Heffelfinger et al. [Citation12] reported its clinical and morphological features. CCs were characterized by female predominance [Citation13]. Other subtypes of chordomas include cellular, poorly differentiated and dedifferentiated. The chondroid subtype accounts for 7–63% of skull base chordomas. It consists of cords and nests of epitheloid cells with vacuolated clear cytoplasm (physaliphorous cells). The matrix, however, resembles neoplastic hyaline cartilage. Like all chordomas, they express cytokeratins and most are immunoreactive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and S100 protein. Brachyury, a nuclear protein associated with notochord differentiation, is the most specific marker of chordoma. Occasionally though, chondroid chordoma may demonstrate only focal cytokeratin expression [Citation10].

In the PPS, chondroid chordomas are rare and only two case reports were found in the literature. One case was of a cervical spine chondroid chordoma with participation of the PPS [Citation14]. Another occurrence in the PPS was reported in 1992 of a chordoma, without subtype classification, which showed a lack of attachment to either the vertebral body or the intervertebral disc [Citation15]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of an isolated chondroid chordoma in the PPS.

Chondroid chordomas are less aggressive than their conventional counterparts and are generally diagnosed in patients between the third and fifth decades of life appearing mostly in the spheno-occipital region. The clinical presentation depends highly on the anatomical location. Magnetic resonance imaging and CT are of great importance for proper diagnosis and surgical planning. They appear as destructive lytic lesions at the skull base and soft tissue masses with occasional dystrophic calcifications. MRI is the preferred imaging modality as it allows better delineation of the tumor and allows for the assessment of its relationship to the adjacent vasculature. These tumors appear hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences. Since they are resistant to chemotherapy, the main treatment modality is complete surgical resection usually followed by adjuvant radiotherapy [Citation9]. Molecular targeted therapy (MTT), e.g. erlotinib and imatinib is an option for advanced chordoma, but it requires more clinical trials to evaluate its safety and efficacy [Citation16].

Classic surgical approaches to the PPS include: trans-cervical, cervical-parotid, trans-parotid, preauricular, and infratemporal fossa approaches. The cervical and cervical-parotid approaches are the most commonly used and a selected number of cases may require single or multiple mandibulotomies. Thus, the selection of the surgical approach must be considered based on the size of the tumor, the structures invaded, and the malignant potential [Citation1]. In this case, a cervical approach provided adequate exposure and adequate resection of the tumor which measured 4 cm. Other cases, however, may present a challenge in the exposure and dissection around the major vessels of the neck and additionally may be adherent to the vertebral facia or vertebral bodies, in which case, consideration of wider approaches may be necessary.

Conclusion

This case presents an unusual chondroid chordoma in PPS with no direct involvement of the axial skeleton. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a parapharyngeal space tumor.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Iglesias-Moreno MC, Lopez-Salcedo MA, Gomez-Serrano M, et al. Parapharyngeal space tumors: fifty-one cases managed in a single tertiary care center. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136(3):298–303.

- Sun F, Yan Y, Wei D, et al. Surgical management of primary parapharyngeal space tumors in 103 patients at a single institution. Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138(1):85–89.

- Pensak ML, Gluckman JL, Shumrick KA. Parapharyngeal space tumors: an algorithm for evaluation and management. Laryngoscope. 1994;104(9):1170–1173.

- Nakahira M, Nakatani H, Takeda T. Syncope as a sign of occult malignant recurrence in the retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal space: CT and MR imaging findings in four cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(7):1257–1260.

- Cicogna R, Bonomi FG, Curnis A, et al. Parapharyngeal space lesions syncope-syndrome. A newly proposed reflexogenic cardiovascular syndrome. Eur Heart J. 1993;14(11):1476–1483.

- Locatello LG, De Cesare JM, Taverna C, et al. Primary parapharyngeal leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97(10-11):E28–e31.

- Krishnamurthy A. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the parapharyngeal space. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14(6):1446–1448.

- Yi WL, Chen TP, Chiu NT, et al. Parapharyngeal ganglioneuroma detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2019;44(3):240–243.

- Erazo IS, Galvis CF, Aguirre LE, et al. Clival chondroid chordoma: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2018;10(9):e3381.

- Wasserman JK, Gravel D, Purgina B. Chordoma of the head and neck: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12(2):261–268.

- Falconer MA, Bailey IC, Duchen LW. Surgical treatment of chordoma and chondroma of the skull base. J Neurosurg. 1968;29(3):261–275.

- Heffelfinger MJ, Dahlin DC, MacCarty CS, et al. Chordomas and cartilaginous tumors at the skull base. Cancer. 1973;32(2):410–420.

- Tsutsumi S, Akiba C, Suzuki T, et al. Skull base chondroid chordoma: atypical case manifesting as intratumoral hemorrhage and literature review. Clin Neuroradiol. 2014;24(4):313–320.

- Motsch C, Grasshoff H, Warich-Kirches M. Interesting case no. 45. Pharyngeal manifestation of chondroid chordoma. Laryngorhinootologie. 2001;80(5):290–292.

- Hampal S, Flood IM, Jones RA. Chordoma of the parapharyngeal space. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(6):549–552.

- Meng T, Jin J, Jiang C, et al. Molecular targeted therapy in the treatment of chordoma: a systematic review. Front Oncol. 2019;9:30.