Abstract

Middle ear osteoid osteomas are rare, and they can be misdiagnosed as otosclerosis. Conductive hearing loss, aural fullness, tinnitus and rarely otorrhoea are presenting symptoms. A rare paediatric case is highlighted here. The aim is to consider this amongst differential diagnosis and the operative technique has also been discussed. A 10-year-old girl with a one-year history of intermittent bloody otorrhoea presented to the Whipps Cross paediatric otology clinic. CT and MRI scan demonstrated an intrinsic lesion centred on the incus. Otoendoscopic examination and radiological investigations deemed the lesion of undetermined significance. A transcanal endoscopic excision of this lesion was performed. Histology revealed a lesion consistent with an osteoid osteoma. Osteoid osteomas of the middle ear represent an important differential diagnosis to consider when assessing patients with otalgia, otorrhea, tinnitus and an associated conductive deafness.

Introduction

Osteoid osteomas are small, non-progressive and benign lesions which form directly from mature bone. Osteoid osteomas should not be confused with osteomas, which are well known in the wider field of otolaryngology as they are often found in the paranasal sinuses, external auditory canal or the calvaria of the skull [Citation1]. Osteoid osteomas are histologically similar to osteoblastomas, with their incidence in the middle ear being extremely rare [Citation2]. They have a male pre-dominance (approximately 2:1) with young adults more likely to be affected, particularly in the second or third decade of life. The incidence under the age of 5 and over the age of 40 is uncommon [Citation3].

Studies analysing the middle ears of skulls have shown an increased prevalence of middle ear osteoid osteomas in ancient civilisations when compared with modern day specimens. Moreover, all the incudal osteomas that were found arose strictly from the medial surface of the incus. This could explain why so few of them are reported in the literature, as the medial incus is poorly visible on normal otoscopy and many patients remain asymptomatic [Citation4].

We present an unusual case of a middle ear osteoid osteoma presenting with bleeding from the ear and unilateral conductive hearing loss.

Case presentation

A 10-year-old female patient of British Asian descent presented to our outpatient clinic with a history of intermittent bleeding from her right ear. The initial referral to the clinic had been made by her GP over a year prior, however due to the Covid-19 pandemic her appointment was delayed. There were multiple emergency department attendances with symptoms of bleeding from the right ear. At the time of presentation in the outpatient clinic her bleeding symptoms had resolved for over a year, but she complained of right otalgia and tinnitus. She denied any relevant family history of hearing loss. She lived with her parents and was up to date with all vaccinations.

Otoscopy revealed a prominent polypous non-pulsatile bright red lesion behind the right tympanic membrane in the pars tensa region extending to the pars flaccida. Her cranial nerve examination was unremarkable. No spontaneous nystagmus was elicited. Otoendoscopic images were taken (Figure ). An audiometry revealed right moderate to severe conductive hearing loss and normal hearing in her left ear.

Figure 1. Otoendoscopic image of right tympanic membrane. White pointer denoting a lesion present in the pars flaccida extending inferiorly to the posterior and superior pars tensa.

A plan was made for the patient to undergo a temporal bone CT scan and MR imaging of the internal auditory meatus (IAM) followed by review in clinic. Whilst awaiting the imaging, the patient went on to present to the emergency department with two further episodes of bloody otorrhea and otalgia from her right ear, which both resolved spontaneously.

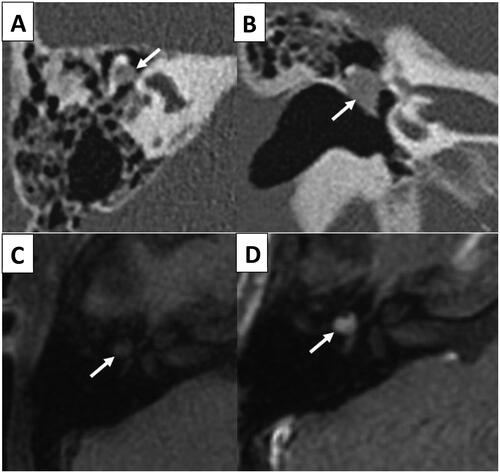

Both the CT and MRI scan demonstrated an intrinsic lesion centred on the incus, involving the body, the long process and abutting the malleolar head. From the combined radiological and otoscopic findings, the differential diagnoses considered included a hemangioma or fibrous dysplasia affecting the incus. (Figure and b depicting axial and coronal images from the non-contrast temporal bone CT, Figure and d showing axial T1 pre and post contrast MRI IAM).

Figure 2. Axial (A) and coronal (B) images from the unenhanced temporal bone CT. The white arrows indicate the abnormal incus that was enlarged and demonstrated a relative abnormal lucency when compared to the rest of the malleus and body/short process of the incus. Axial T1 pre contrast (C) and axial T1 post contrast (D) images from an MR IAM. The white arrows demonstrate the abnormal expansile lesion centred on the incus with evidence of contrast enhancement.

The patient went on to undergo a right transcanal endoscopic exploratory tympanotomy. A tympanomeatal flap was raised and tympanotomy was performed. A firm, bony lesion was identified separate from the malleus and derived from the medial surface of the incus, involving the posterior and superior tympanic membrane. The chorda tympani nerve was involved in this lesion. This lesion was excised en-bloc, and the stapes was unstable after excision of this lesion, therefore an ossiculoplasty was not performed and intended to be staged. Underlay temporalis fascia was used to reconstruct the tympanic membrane.

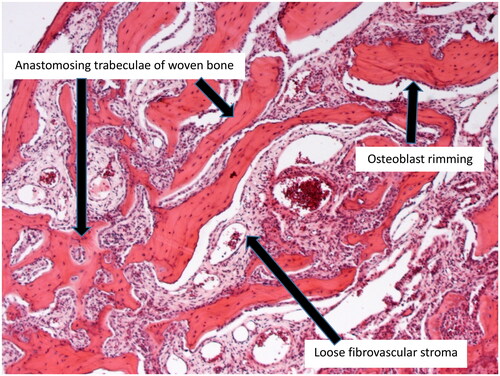

The lesion measured 5 mm x 3 mm x 3 mm and histopathological examination revealed a benign osteoid osteoma (Figure ).

Discussion

In the literature there are currently 44 cases of middle ear osteoid osteoma reported, with a mean age at presentation of 28 years. Of these, the majority (72.2%) presented with conductive hearing loss [Citation5]. They were most frequently found to originate from the promontory (38.6%). There were other sites of origin, including ossicles (18.1%), epitympanum (13.6%), pyramidal process (9.1%), hypotympanum (6.8%), lateral semicircular canal (6.8%), facial nerve canal (4.5%), cochleariform process (2.3%), annulus (2.3%) and aditus (2.3%). There are only four reported cases of osteoid osteoma of the incus [Citation6], of which two were associated with cholesteatoma. Six cases presented in pre-pubescent children and, of those, only one presented on the incus. To date, there have been no reported cases of middle ear osteoid osteoma presenting with ear bleeding.

In the literature, Eustachian tube balloon dilation combined with a cartilage-perichondrium tympanoplasty is thought to further increase the closure rate without affecting audiometric results [Citation7].

The exact aetiology of the ear bleeding remains unknown. The probable cause is that there was involvement of the posterior tympanic membrane by the lesion, resulting in bloody otorrhoea.

Temporal bone osteomas can arise from every temporal bone osteogenetic subsite (mastoid, tympanic, squama, petrous and styloid), the most common of which is a pedunculated external auditory canal osteoma (EACO), Symptoms may include hearing loss, cerumen impaction, aural fullness and more, and they usually occur after at least 80% external auditory canal obstruction has been achieved [Citation8],

On imaging, the lesion was intrinsic to the incus. The ground glass density resulted in the proposed diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia, which can also demonstrate enhancement on MR imaging. A haemangioma of the ossicles is rare and, whilst this can demonstrate enhancement, the expansile nature of the lesion is atypical.

The presence of plump osteoblasts rimming trabeculae of woven bone and the presence of intervening loose vascularised stroma are the major histological features distinguishing osteoid osteoma from fibrous dysplasia. Fibrous dysplasia lacks conspicuous osteoblastic rimming and has a more compact fibrous stroma. Clinically, osteoid osteomas are notoriously painful lesions.

The aetiology of middle ear osteomas remains unexplained. There is some evidence of genetic predisposition, with literature supporting evidence of a familial link between siblings [Citation9]. Several cases of middle ear osteoid osteoma presenting with cholesteatoma have also been reported, suggesting a possible inflammatory component to their aetiology [Citation10].

Conclusion

We describe a rare case of a middle ear incudal osteoid osteoma presenting with bloody otorrhea, which, to our knowledge, has not been reported in the literature to date. This case suggests that clinicians should consider osteoid osteoma in the differential diagnoses when assessing patients with otalgia, bloody otorrhea and an associated conductive deafness with or without tinnitus.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent: written informed consent for publication was given by the parents.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the department of ENT at Whipps Cross University Hospital.

Disclosure statement

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Greenspan A. Benign bone-forming lesions: osteoma, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1993;22(7):485–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00209095.

- Viswanatha B. Characteristics of osteoma of the temporal bone in young adolescents. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90(2):72–79. doi: 10.1177/014556131109000207.

- Noordin S, Allana S, Hilal K, et al. Osteoid osteoma: contemporary management. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2018;10(3):7496. doi: 10.4081/or.2018.7496.

- Arensburg B, Belkin V, Wolf M. Middle ear pathology in ancient and modern populations: incudal osteoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125(11):1164–1167. doi: 10.1080/00016480510043431.

- Temirbekov D, Celikyurt C. Middle ear osteoma causing eustachian tube obstruction: a case report and literature review. J Otol. 2020;15(4):161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.joto.2020.06.003.

- Yoon YS, Yoon YJ, Lee EJ. Incidentally detected Middle ear osteoma: two cases reports and literature review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35(4):524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.03.010.

- Immordino A, Sireci F, Lorusso F, et al. The role of cartilage-perichondrium tympanoplasty in the treatment of tympanic membrane retractions: systematic review of the literature. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;26(3):e499–e504. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1742349.

- Argaman A, Oron Y, Handzel O, et al. Questioning the value of stalk drilling after external auditory canal osteoma excision: case series, literature review, and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;281(1):51–59. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-08074-x.

- Thomas R. Familial osteomas of the Middle ear. J Laryngol Otol. 1964;78(9):805–807. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100062794.

- Yamasoba T, Harada T, Okuno T, et al. Osteoma of the Middle ear: report of a case. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116(10):1214–1216. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870100108025.