Abstract

Malignant glomus tumors are rare mesenchymal tumors arising from the smooth muscle cells of the glomus body. Primary malignant glomus tumors of the thyroid are atypical. An 80-year-old man presented with a right thyroid tumor on computed tomography (CT) and was suspected of having multiple bilateral pulmonary metastases. The right lobe of the thyroid gland was accompanied by a low-density tumor and calcification inside, and infiltration into the trachea and cervical esophagus was deduced. Core needle biopsy (CNB) confirmed that round to polygonal atypical cells were growing in sheet form around the vascular endothelial cells. Immunohistochemistry results were positive for vimentin and smooth muscle actin (SMA) but negative for pan-cytokeratin and S-100 protein. Chemotherapy with doxorubicin was initiated. However, due to the progression of the disease, doxorubicin was replaced with pazopanib. His condition deteriorated further, and he died 3 months after the treatment. Overall, this disease has a poor prognosis.

Introduction

Most glomus tumors are rare benign mesenchymal perivascular tumors that account for approximately 2% of soft tissue tumors [Citation1,Citation2]. The most common reported location is the distal extremities, particularly the hand, wrist, foot, and subungual region [Citation1,Citation2]. Malignant glomus tumors can infrequently occur in an extracutaneous site such as the stomach, kidney, uterus, and lung [Citation3–7]. Primary malignant glomus tumors of the thyroid are also rare [Citation8,Citation9]. To the best of our knowledge, only two cases of primary malignant glomus tumors of the thyroid have been reported in the English literature [Citation8,Citation9]. Herein, we report another patient that survived for approximately 3 months after the discovery of a malignant glomus tumor of the thyroid.

Case report

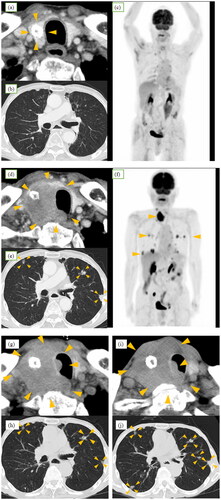

An 80-year-old man presented with a right thyroid mass on computed tomography (CT) and was suspected of having multiple bilateral pulmonary metastases following investigations for hoarseness and swallowing difficulties. He had a medical history of hypertension and subsequent surgery and chemoradiotherapy for esophagogastric junction cancer 8 years ago. Two years ago, local recurrence was observed after treatment, leading to distal gastrectomy with esophagogastrostomy. The surgery resulted in complete resection, and the pathological findings revealed adenocarcinoma. Eight months prior to discovery of the mass, CT scans as part of routine follow-up revealed only coarse calcified lesions in the right lobe of the thyroid, with no evidence of metastasis to the lungs or throughout the body (Figure ). He presented with hoarseness and swallowing difficulties.CT scan was performed for detailed examination, revealing a right thyroid mass. The mass was 36 × 44 mm in size and of low density, and CT findings were suggestive of infiltration into the trachea and cervical esophagus (Figure ). Multiple pulmonary nodules were identified (Figure ). Fiber-optic laryngoscopic examination revealed right vocal cord palsy. On 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-CT, accumulation was observed in the right lobe of the thyroid and lung nodules, with no uptake detected in other organs, including the esophagus (Figure ). Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) results suggested that the lesion was malignant. Subsequently, a malignant glomus tumor was diagnosed by core needle biopsy (CNB). Pulmonary nodules were considered distant metastases.

Figure 1. Time course of computed tomography (CT). (a–c) Eight months prior to discovery of the mass, only coarse calcified lesions were detected in the right lobe of the thyroid (arrowheads), with no evidence of metastasis to the lungs or throughout the body. (d) and (e) Neck and chest CT before treatment indicating ∼4-cm hypoechoic mass in the right lobe of the thyroid gland, suggesting infiltration into the trachea and cervical esophagus and multiple nodules in lungs (arrowheads). (f) Positron emission tomography-CT before treatment demonstrating approximate accumulation in the right lobe of the thyroid and lung nodules, with no uptake detected in other organs. Although partial accumulation was noted in the small intestine, it was considered a false positive, as no lesions were identified on CT images. (g) and (h) Enlargement of tumor and infiltration into the trachea after treatment with doxorubicin. Slight shrinkage of pulmonary nodules (arrowheads) was observed. (i) and(j) Further progression of tumor and pulmonary nodules after treatment with pazopanib (arrowheads).

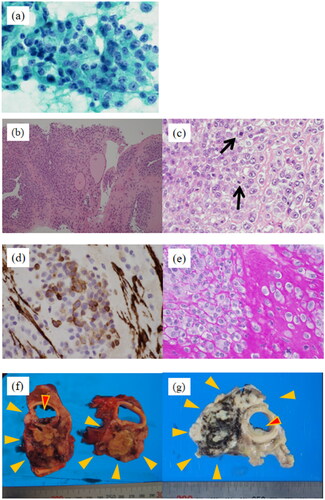

FNAC revealed the aggregation of atypical cells with poor binding that had enlarged nuclei, increased amounts of chromatin, and distinct nucleoli (Figure ). The CNB indicated round polygonal atypical cells with vascular heteromorphic nuclei, distinct nucleoli, and eosinophilic cytoplasm growing in sheet form around vessels (Figure ). Basement membranous material was demonstrated by periodic acid-Schiff reaction (Figure ). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Figure ) but negative for pan-cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), S-100 protein, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and CD34 (Table ).

Figure 2. Pathology images. (a) Accumulation of atypical cells with enlarged nuclei, increased amounts of chromatin, and distinct nucleoli with poor binding on aspiration cytology (Papanicolaou staining). (b) Round to polygonal atypical cells with round nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm growing in sheet form around vessel (low magnification, hematoxylin & eosin staining). (c) The arrows in the image indicate increased mitotic activity (high magnification, hematoxylin & eosin staining). (d) Tumor cells immunohistochemically positive for smooth muscle actin. (e) Basement membranous material demonstrated by periodic acid-Schiff reaction. (f) Thyroid lesion (largest), forming 8.0 × 5.6 × 3.6-cm mass (yellow arrowheads) in contact with trachea (red arrowheads). (g) White mass which formed (yellow arrowheads) and infiltrated the trachea (red arrowheads).

Table 1. Immunohistochemistry results.

The patient was initially treated with doxorubicin. At the end of the first course of treatment, the lung metastases responded slightly. However, as tumor progression and intratracheal infiltration were observed (Figure ), the patient was treated with pazopanib as a second-line chemotherapy. Mild airway constriction was observed due to tumor enlargement (Figure ), and the patient experienced respiratory distress. Although we suggested palliative tracheostomy, the patient did not agree with the suggestion. His condition deteriorated further, and he died three months after the treatment.

An autopsy was performed. The cause of death was respiratory failure due to lung metastasis and lobar pneumonia. Additional immunochemical staining performed after autopsy confirmed the malignant glomus tumor diagnosis (Table ). As there were no other lesions suspected of being the primary tumor, it was diagnosed as a malignant glomus tumor of thyroid origin. The pulmonary nodules were metastases, and pleural, adrenal, and skin metastases were also observed. Pathological findings demonstrated no effect of chemotherapy.

Discussion

Most glomus tumors are benign and occur in the skin or superficial soft tissues [Citation2,Citation10]. Infrequently, malignant glomus tumors with slight or even absent normal glomus bodies have been reported in visceral organs, such as the stomach, kidney, uterus, and lung [Citation3–7]. Therefore, diagnosis is often postponed or even missed. Glomus tumors should not be confused with “glomus tympanicum” or “glomus jugulare,” which represent paraganglioma [Citation11].

A search of the PubMed and Google Scholar databases from 1969 to October 2023 using the keywords ‘malignant glomus tumor’ and ‘thyroid’ revealed that only two cases of malignant glomus tumors of thyroid origin have been reported in the English literature (Table ). In the present case, the patient survived for only approximately three months after the incidental discovery of the thyroid mass. The other two reported cases also died (at 30 and 6 months, respectively) [Citation8,Citation9]. These data suggest that this disease has a poor prognosis, including metastasis to distant organs.

Table 2. Case report of primary malignant glomus tumor of the thyroid gland.

The histology of glomus tumors is characteristic. However, few cytological reports have described glomus tumors [Citation3,Citation8,Citation12]. Tumors are composed of uniform round to oval cells seen in tight or loose aggregated clusters or 3-dimensional patterns. The nuclei are round to oval and uniform. Occasionally, thin spindle-shaped capillary endothelial cells are present around the tumor cell clusters [Citation3,Citation8].

In our case, atypical cells with enlarged nuclei, increased amounts of chromatin, and distinct nucleoli were observed. Although the specimen was abnormal for a thyroid tumor and the histological diagnosis could not be confirmed, it had some features suggestive of malignancy (Figure ). According to the World Health Organization classification, the criteria of malignant glomus tumors are as follows: (1) marked nuclear atypia and any level of mitotic activity or (2) atypical mitotic figures [Citation2].

Histologically, glomus tumors are composed of sheets of rounded and uniform glomus cells with amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm and centrally placed round nuclei. The cell borders are sharp, with well-defined periodic acid-Schiff–positive or type IV collagen immunohistochemical staining–positive basement membranes. A prominent capillary system is present, usually around the mass [Citation1,Citation2,Citation13]. Typically, immunohistochemical staining is positive for SMA and collagen type IV but negative for cytokeratin, S-100 protein, desmin, CD31, and CD34 [Citation1,Citation13]. In the present case, round to polygonal atypical cells with round nuclei with mitotic figures were observed growing in sheet form around vascular endothelial cells (Figure ). Basement membranous material was demonstrated by periodic acid-Schiff reaction (Figure ). Collagen type IV staining could not be performed at our hospital due to a lack of reagents.

Due to the rarity of glomus tumors in visceral organs, a diagnosis cannot be made with aspiration cytology alone. Only one case diagnosed by CNB has been reported [Citation13]. In the present case, CNB was also useful.

The differential diagnosis of malignant glomus tumors is extensive. Most of the major thyroid cancers, such as papillary carcinoma, follicular carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, and malignant lymphoma, can be ruled out by histopathology and immunochemical staining of cytokeratin, leukocyte common antigen, and S-100 protein. Differential diagnoses of malignant glomus tumors in the thyroid gland further include paraganglioma [Citation11], hemangiopericytoma [Citation14], epithelioid leiomyosarcomas [Citation15], and rhabdomyosarcoma [Citation10].

Immunochemical staining helps to provide a definitive diagnosis. Paragangliomas stain positive for S-100 protein and synaptophysin [Citation11]. Hemangiopericytomas stain positive for CD34 but negative for SMA [Citation8,Citation14]. Epithelioid leiomyosarcomas stain positive for desmin, keratin, and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) [Citation1,Citation15]. Rhabdomyosarcomas stain positive for desmin, MyoD1, and myogenin [Citation1,Citation10].

The differential diagnosis of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is important in rapidly growing cancer cases [Citation8]. An ATC is the most clinically aggressive of the epithelial tumors [Citation8,Citation16]. Immunochemical staining of ATC often displays keratin staining [Citation16]. If the well-differentiated component is absent and immunohistochemistry cannot prove epithelial differentiation, differential diagnosis from sarcoma can be very difficult. Two characteristic histological features help distinguish sarcomatoid undifferentiated carcinoma from true sarcoma: the presence of angular necrotic foci and the tendency of tumor cells to invade large veins and arteries [Citation16]. On the other hand, identification of typical glomus tumor regions is key in the diagnosis of atypical glomus tumors [Citation1].

Although the possibility that the biopsy specimen was collected from a section that had differentiated into a glomus tumor could not be ruled out in the present case, the likelihood of ATC was low due to the clear differentiation tendency. Because primary malignant glomus tumors of the thyroid are extremely rare, the epithelial tumor diagnosis was ruled out and the patient was diagnosed with a glomus tumor by exclusion after CNB; however, it was difficult to make a definitive diagnosis.

If the tumor is localized, surgical excision is indicated. It is important to have a sufficient margin so that a wide local excision can be performed. However, there are cases involving the head and neck where it may be difficult to secure a sufficient margin for excision [Citation13]. Radiation therapy may provide temporary local control, such as pain control, but does not lead to a complete response [Citation4,Citation13].

No chemotherapy for metastatic or unresectable glomus tumors has been established [Citation5]. To date, the first-line standard regimen for advanced mesenchymal tumors is anthracycline-based chemotherapy [Citation5,Citation17,Citation18], which is also used in malignant glomus tumors. Pazopanib, an oral multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitor, may be selected as the second-line chemotherapy in metastatic non-lipomatous sarcoma [Citation5,Citation18,Citation19].

Previous studies of chemotherapy for malignant glomus tumors have described treatment with adriamycin, doxorubicin, epirubicin, ifosfamide, and cyclophosphamide [Citation5,Citation6,Citation13]. However, none of these treatments have produced significant effects. Treatment with pazopanib is generally effective [Citation5,Citation7,Citation13], but in some cases, it could not be continued due to adverse events and was ineffective. In the present case, doxorubicin demonstrated limited effectiveness. Additionally, pazopanib was challenging to sustain adequately due to a decline in overall health status of the patient.

Malignant glomus tumors have a poor prognosis, which is even worse when distant metastases are present. Folpe et al. [Citation1] described a mortality rate of 29% in cases with distant metastasis. Dong et al. [Citation6] suggest that distant metastasis indicates a poor prognosis in cases of primary malignant glomus tumors of the lung. Prognosis and mortality rate can probably be expected to be even worse in cases with primary malignant glomus tumors of the thyroid gland, given that all three cases reported to date died within 3 years of diagnosis [Citation8,Citation9]. In the present case, it was difficult to continue chemotherapy due to the progression of the disease and the generally poor condition of the patient.

Conclusion

Primary malignant glomus tumors of the thyroid gland are rare and have a poor prognosis.

Informed consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the daughter of the patient.

The identity of the patient has been protected.

Funding

None.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(1):1–12. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200101000-00001.

- Specht K, Antonescu CR. World Health Organization classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone tumours. Glomus tumours. 5th ed. Chapter 1. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. p. 179–182.

- Gu M, Nguyen PT, Cao S, et al. Diagnosis of gastric glomus tumor by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. A case report with cytologic, histologic and immunohistochemical studies. Acta Cytol. 2002;46(3):560–566. doi: 10.1159/000326878.

- Lamba G, Rafiyath SM, Kaur H, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of kidney: the first reported case and review of literature. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(8):1200–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.11.009.

- Colia V, Fontana AP, Sandrucci S, et al. Response to chemotherapy with epirubicin plus ifosfamide and to tyrosine kinase inhibitor in a metastatic malignant glomus tumor. J Case Rep Images Oncology. 2022;8(1):4–8.

- Dong LL, Chen EG, Sheikh IS, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the lung with multiorgan metastases: case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1909–1914. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S89396.

- Kumar N, Lata K, Barwad A, et al. Tracheal glomus tumor: an aggressive rare neoplasm. Lung India. 2020;37(3):285–286. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_544_19.

- Chung DH, Kim NR, Kim T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the thyroid gland where is heretofore an unreported organ: a case report and literature review. Endocr Pathol. 2015;26(1):37–44. doi: 10.1007/s12022-014-9352-5.

- Liu Y, Wu R, Yu T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the thyroid grand: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2019;47(6):2723–2727. doi: 10.1177/0300060519844872.

- Jayaraj G, Sherlin HJ, Ramani P, et al. Malignant glomus tumour of the head and neck–A review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2019;31(3):228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoms.2018.12.009.

- Asa SL, Ezzat S, Mete O. The diagnosis and clinical significance of paragangliomas in unusual locations. J Clin Med. 2018;7(9):280. doi: 10.3390/jcm7090280.

- Vidyavathi K, Udayakumar M, Prasad CB, et al. Glomus tumor mimicking eccrine spiradenoma on fine needle aspiration. J Cytol. 2009;26(1):46–48. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.54871.

- Wolter NE, Adil E, Irace AL, et al. Malignant glomus tumors of the head and neck in children and adults: evaluation and management. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(12):2873–2882. doi: 10.1002/lary.26550.

- Higashi-Shingai K, Mori K, Nakanishi K, et al. Hemangiopericytoma of the head and neck region: report of two cases. Pract Otol. 2008;101(12):937–941. doi: 10.5631/jibirin.101.937.

- Sindwani R, Matthews TW, Thomas J, et al. Epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the larynx. Head Neck. 1998;20(6):563–567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199809)20:6<563::AID-HED12>3.0.CO;2-L.

- Ragazzi M, Ciarrocchi A, Sancisi V, et al. Update on anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: morphological, molecular, and genetic features of the most aggressive thyroid cancer. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:790834–790813. doi: 10.1155/2014/790834.

- Gronchi A, Miah AB, Dei Tos AP, et al. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(11):1348–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.006.

- Japanese Orthopaedic Association. Clinical practice guidelines on the management of soft tissue tumors. 3rd ed. Japan: Nankodo; 2020. p. 71–73.

- van der Graaf WTA, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5.