Abstract

Diagnostic mediastinoscopy is a procedure with well-known serious complications: Hemorrhage, mediastinitis, pneumothorax and recurrent nerve damage. Esophageal perforation is a less known potentially life-threatening complication. Here the case of a young man with an iatrogenic esophageal perforation following a diagnostic mediastinoscopy is presented with a literary review of previously published cases.

Introduction

Cervical mediastinoscopy was introduced by the Swedish otolaryngologist Erik Carlens in the late 1950s [Citation1,Citation2]. It is a minimally invasive procedure where a small incision above the jugulum is used to reach the mediastinum with a rigid mediastinoscope. Today it is mainly used for diagnostic sampling of pretracheal lymph nodes in the diagnostic work-up for both suspected malignant and non-malignant diseases. The surgical field is located in close proximity to major vessels such as the brachiocephalic artery, the aortic arch, the right pulmonary artery and the Azygos veins with potential for hemorrhagic complications [Citation2,Citation3]. It is also adjacent to the left recurrent nerve where damage can result in vocal cord paralysis. Perhaps one of the least anticipated complications is damage to the esophagus, which for the most part lies securely covered by the trachea. However, distal to the carina it lies in close proximity to the lymph nodes at levels 4 and 7. When sampling these nodes there is a risk for damage to the esophagus resulting in a life-threatening perforation with mediastinitis. Here we report a case of a young man with an esophageal perforation during mediastinoscopy successfully treated with an esophageal stent and a review of the literature.

Case report

A 32-year old man with a previous history of paroxysmal vertigo was under investigation for long-term coughing without clinical signs and laboratory findings of infection. Sarcoidosis was suspected based on radiological findings of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. EBUS (Endo Bronchial Ultra Sound) guided fine needle aspiration had failed to obtain diagnostic samples, he was then referred to the otolaryngology department for a diagnostic mediastinoscopy. The procedure with extirpation of an enlarged lymph node in level 4 R was uneventful except for a minor hemorrhage. SURGICEL® FIBRILLAR™ was applied to manage the hemorrhage and the cervical wound was then closed. In this case a regular mediastinoscope with separate optics was used instead of a video-mediastinoscope.

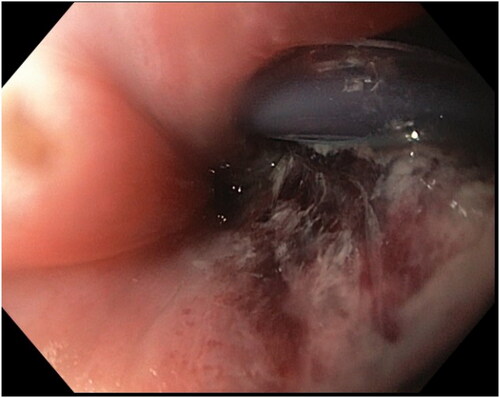

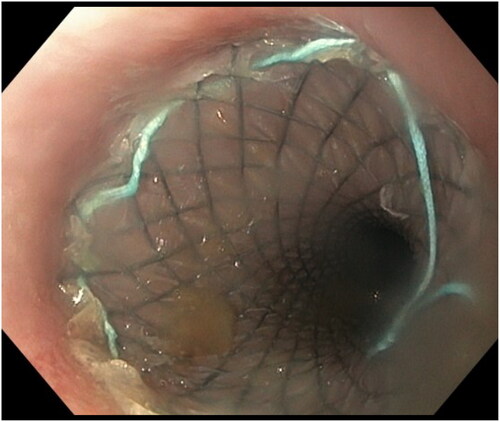

The patient was discharged on postoperative day one. He was feeling well except some pain when coughing. He was readmitted eleven hours later presenting with increased pain, fever (38.5 0C) and dyspnea. The oxygen saturation varied between 90 and 95%.The leukocyte count was 16.6 x109/L and the C-reactive protein (CRP) was 110 mg/L. An acute CT-scan was performed showing mediastinal air and some foreign body material in the mediastinum. The initial assessment was that this was air entrapped during the procedure and SURGICEL® and that he had a mediastinitis caused by bacteria from the cervical incision. The patient was hemodynamically stable and was readmitted to the ENT ward with intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam. On the second postoperative day both the respiratory rate and the heart rate was increased (32 bpm and 105 bpm respectively). The leucocytes count was 13.8 x109/L and CRP was 183 mg/L. The oxygen saturation was 92% and oxygen with a 4 L/minute flow was administered. On the third postoperative day the patients conditioned worsened with increased fever (39.3 0C) and severe back pain. An emergency CT-scan was performed with per oral contrast that revealed an esophageal perforation (Figure ). He was then taken to the operating room where a mediastinotomy was performed through a right-sided anterolateral thoracotomy. Fluid was present in the pleura. Anterior to the esophagus an abscess was found and incised. Beneath, the esophagus showed signs of severe inflammation from the Azygos veins to the diaphragm and a 4-5 cm perforation was observed (Figure ). A Blake drainage was placed in the mediastinotomy cavity and a French 32 drain in the pleura. The defect was neither suitable for surgical repair nor Eso-Sponge® drainage treatment and it was decided to treat the perforation with a covered Wallstent™ (28/23/125 mm) (Figure ). The patient was then transferred to the surgical ward for post-operative care. The stent was successfully removed after 25 days and a control CT-scan showed no leakage. He was discharged 41 days after re-admission and has since recovered fully. The pathological anatomical diagnosis of the sampled lymph node was sarcoidosis and he has received corticosteroid treatment.

Figure 1. CT-scan three days after mediastinoscopy confirms an esophageal perforation with contrast leakage.

Discussion

Mediastinoscopy is usually a safe procedure with uncommon but well-known serious and even life threatening complications [Citation2,Citation3]. Esophageal perforation with mediastinitis is not a complication as well-known as hemorrhage and vocal cord paralysis. There are a few previously published case reports of this complication [Citation3–6] (Table ). Dernevik et al. (1985) reported two cases treated with surgical repair resulting in esophageal-cutaneous fistulas that was treated with a second operation in one case and conservative treatment in the other [Citation4]. Pereszlenyi et al. (2003) reported a case successfully treated with surgical repair with a pleural flap [Citation5]. Weiss et al. (2015) reported a case where a patient with esophageal perforation after mediastinoscopy was treated with a delayed thoracotomy and an esophageal stent [Citation6]. Esophageal perforation has been reported to have a mortality between 4.8 and 20% [Citation7,Citation8], and that a delayed treatment (> 24 h) after perforation can lead to increased mortality [Citation9]. Shaker et al. reported that in four out of the five patients that died treatment was delayed more than 24 h after perforation suggesting a ‘24-h golden rule’ [Citation9].

Table 1. Previously published cases of iatrogenic esophageal perforation following mediastinoscopy with management and outcome.

It is important that the patient is informed about all possible risks before treatment by a surgeon that performs this procedure. However, since this complication is not widely reported the patients are probably not informed about it before mediastinoscopy. Perforation of the esophagus with mediastinitis should be suspected postoperatively in patients with any of these symptoms and clinical signs: increased pain, increased respiratory and heart rate, desaturation, fever, elevated leukocyte count and CRP. The patients should be monitored post-operatively and mediastinoscopy is therefore not a procedure suited for outpatient surgery. Although non-operative management may be an option in selected patients [Citation10,Citation11], the mainstay of treatment for iatrogenic esophageal perforation is surgical or endoscopic closure of the defect with adequate drainage and decompression of the esophagus and stomach [Citation10]. This may however not be possible when the diagnosis is delayed. In the case reported here both the diagnosis and the treatment of the perforation was delayed. Treatment with thoracotomy and drainage and stenting was performed approximately 86 h after mediastinoscopy. This is well past the so-called ‘24-h golden rule’ suggested in an earlier publication [Citation9]. The patient in this case, however, was young and otherwise healthy and the outcome could have been different in an older patient with pulmonary and cardiovascular comorbidities. Video-mediastinoscopes provides a superior visualization of the mediastinal surgical field but the trade-off is that it is bulkier than the traditional mediastinoscope often requiring a larger cervical incision. The authors recommend the use of a video-mediastinoscope when the tissue that should be sampled is located at or below the level of carina.

Conclusion

Esophageal perforation is a relatively unknown life-threatening complication to mediastinoscopy that should be anticipated by physicians performing the procedure.

Informed consent

Informed consent for the publication of clinical information and images was obtained from the patient.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Carlens E. Mediastinoscopy: a method for inspection and tissue biopsy in the superior mediastinum. Dis Chest. 1959;36(4):343–352. Epub 1959/10/01. doi: 10.1378/chest.36.4.343.

- Kirschner PA. Cervical mediastinoscopy. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1996;6(1):1–20. Epub 1996/02/01.

- Puhakka HJ. Complications of mediastinoscopy. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103(3):312–315. Epub 1989/03/01. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100108795.

- Dernevik L, Larsson S, Pettersson G. Esophageal perforation during mediastinoscopy–the successful management of 2 complicated cases. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;33(3):179–180. Epub 1985/06/01. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014112.

- Pereszlenyi A, Jr., Niks M, Danko J, et al. Complications of video-mediastinoscopy–successful management in four cases. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2003;104(6):201–204. Epub 2003/11/05.

- Weiss AJ, Salter B, Evans A, et al. Esophageal perforation following cervical mediastinoscopy: a rare serious complication. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(12):E678–81. Epub 2016/01/23. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.20.

- Chirica M, Champault A, Dray X, et al. Esophageal perforations. J Visc Surg. 2010;147(3):e117-28. Epub 2010/09/14.

- Hauge T, Kleven OC, Johnson E, et al. Outcome after iatrogenic esophageal perforation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(2):140–144. Epub 2019/03/13. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1575464.

- Shaker H, Elsayed H, Whittle I, et al. The influence of the ‘golden 24-h rule’ on the prognosis of oesophageal perforation in the modern era. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38(2):216–222. Epub 2010/03/23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.030.

- Chirica M, Kelly MD, Siboni S, et al. Esophageal emergencies: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14(1):26. Epub 2019/06/06. doi: 10.1186/s13017-019-0245-2.

- Abbas G, Schuchert MJ, Pettiford BL, et al. Contemporaneous management of esophageal perforation. Surgery. 2009;146(4):749–756. discussion 55-6. Epub 2009/10/01. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.058.