ABSTRACT

COVID-19 pandemic has posed an unprecedented threat to both public health and the global economy. In an effort to manage and contain this pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has prioritised laboratory testing (https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—16-march-2020). We examine the testing capacity of the laboratory system in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to WHO, gold standard for COVID-19 diagnosis is real-time reverse-transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). However, this molecular technique is not widely used in Ghana for disease diagnosis because of lack of infrastructure, lack of trained laboratory staff, high maintenance cost, and scarcity of reagents. Ghana has a three-tier health delivery system, with limited molecular diagnostic capacity. Three of the four public health laboratories (PHLs) have the capacity to perform molecular diagnosis of certain diseases. There are two main biomedical research institutions that are well-equipped to perform various molecular diagnostic tests. Nonetheless, their testing capacity is significantly limited in critical situations such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to testing backlogs and delays in returning test results at early stages of the pandemic. In an effort to address this situation, capacities of PHLs and nonclinical laboratories have been increased. Plans to use GeneXpert platform in certain areas of the country have been instituted in sixteen facilities, following system upgrades, risk assessments, and quality-checks. Enhanced molecular diagnostic testing in Ghana will help ensure a swift, accurate, and timely response to COVID-19 and future outbreaks. The data gained from these testing improvements may also help stimulate a robust bioeconomy because they can be used to improve the health of Ghanaians, as well as increase productivity through the implementation of data-driven and evidence-based policies. As outlined in WHO’s Joint External Evaluation report for Ghana, the country faces several challenges, including the need to build strong laboratory systems and capacities that connect disease-specific areas.

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which started as an outbreak in Wuhan, People’s Republic of China, in December 2019, emerged as a public health emergency of international concern on January, 30, 2020. Six weeks later, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease a global pandemic. As of 15 February 2021, there have been 108,863,195 confirmed cases of COVID-19 globally, with over 2 million deaths (Hopkins, Citation2020), resulting in an overall case-fatality rate of 2.2%. To date, 192 countries/territories have been affected. The mode of transmission between people is primarily through respiratory droplets (from coughing and sneezing) and indirectly through fomites (WHO, Citation2020b). Common symptoms include fever, cough, and shortness of breath (UNICEF, Citation2020). Currently, there is no antiviral treatment against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, however, a few vaccines have received emergency use authorisation (EUA) for use in many countries (CDC, Citation2020a; WHO, Citation2020c, Citation2021). Containment is possible only by case finding, contact tracing, and quarantine during the incubation period (between 2–14 days) (WHO, Citation2020d). As part of the global response to manage and contain spread of the virus, WHO has placed enormous emphasis on laboratory testing because of undifferentiated clinical symptoms that could be attributed to multiple causes, including SARS-CoV-2. Many countries such as South Korea and Germany intensified their testing capacities and achieved significant progress in containing the spread of the virus (TheLocal, Citation2020). All continents have had COVID-19 cases, with Africa and Antarctica being the least impacted by this deadly pandemic as of December 2020 (Bostock, Citation2020; DW, Citation2021). Although the number of reported cases on the African continent has not been as high as other parts of the world, experts estimate increases in cases over the coming months. As of 18 February 2021, there were 3,754,326 reported cases and 98,520 deaths in Africa (ECDC, Citation2021), compared with 48,933,836 cases and 1,152,349 deaths in America (Hopkins, Citation2020) and 35,633,482 cases and 805,691 deaths in Europe (ECDC, Citation2021; Hopkins, Citation2020). In Ghana, more than 75,000 COVID-19 cases have been confirmed in all 16 regions, with 533 recorded deaths and 67,000 recoveries as of 15 February 2021 (Ghana-Health-Service, Citation2020b). With the current global shortages in testing kits, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other critical consumables needed for SARS-CoV-2 testing, rapid scale-up of testing capacities in Africa and specifically Ghana have been affected (Andy, Citation2020). We seek to assess the Ghanaian laboratory infrastructure and identify challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, as laboratory testing increases.

Types of COVID-19 tests

There are currently two main types of tests performed to diagnose COVID-19: the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and the antigen test. The NAAT detects the presence of SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) in respiratory specimens, and the antigen test detects the presence of the nucleocapsid viral antigen (CDC, Citation2020b; Corporation, Citation2020), to determine whether a person is infected with the virus. However, the WHO recommendation states that the NAAT should be used to diagnose and confirm COVID-19 due to its high sensitivity/specificity compared to other methods (WHO, Citation2020e). The most common NAAT utilised is the reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Additionally, three other types of tests can be performed: an antibody test, viral sequencing, and viral culture (CDC, Citation2020c; WHO, Citation2020f). The antibody test is used to detect antibodies such as IgM and IgG to SARS-CoV-2, and this aids in determining recent or past infection (CDC, Citation2020c). Although this may be particularly useful for making informed clinical decisions about persons who have presented late in their illness, it is mostly recommended for surveillance purposes (prevalence studies) and research. Viral sequencing and culture methods can also be used; however, they are laborious and time-consuming.

Importance of laboratory testing

Testing for SARS-CoV-2 plays a critical role in understanding the virus and its rate of spread. Testing is one of the most effective tools to slow down and reduce the spread and impact of the virus. Using testing, infected individuals can be identified, isolated from the healthy population, and managed effectively; in addition, contact tracing can be used to identify those who need to be quarantined, if necessary (Hellewell et al., Citation2020). With effective testing, communities with increases in cases can be identified, which can help determine where to allocate limited medical resources and staff. Data from SARS-CoV-2 testing can also be used to determine which interventions should be implemented, including movement or lockdown restrictions for communities, districts, or regions, which can affect the economy. In Ghana, laboratory testing has been a challenge since the emergence of COVID-19 due to lack of four essential components: infrastructure, equipment, trained laboratory professionals, and reagents and consumables. However, there has been significant improvement in all these areas.

Laboratory structure in Ghana and its impact on COVID-19 testing

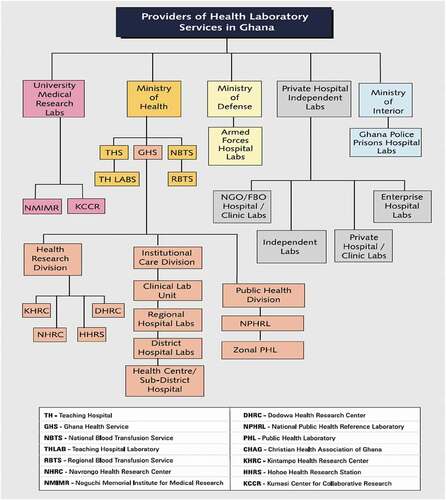

The Ghana Health Service (GHS) has three administrative levels and five functional levels. The administrative levels are national, regional, and district levels, whereas the functional levels comprise the administrative levels, with two additional levels: sub-district and community levels (Ghana-Health-Service, Citation2020a). The health delivery system in Ghana has three tiers: primary (health care and community centres), secondary (district hospitals), and tertiary (regional and teaching hospitals). From the public health perspective, secondary and tertiary levels have functional laboratories () for phenotypic investigations of infections but lack sufficient molecular diagnostic capacity. At the national level, the Public Health Division of GHS has a National Public Health and Reference Laboratory (NPHRL) in Accra, and three zonal public health laboratories (PHLs) are in Kumasi, Tamale, and Sekondi. These four PHLs serve as infectious disease testing centres that provide diagnostic support to Ghana during disease outbreaks. With the execption of the Sekondi PHL, the others currently have capacity to perform molecular testing to diagnose selected diseases. There are five teaching hospitals with well-equipped laboratories capable of conducting routine diagnostic tests. However, only two of these laboratories have recently been equipped to perform COVID-19 testing. Even though none of the current regional hospitals laboratories have the capacity to perform molecular testing, most of them have either received PCR machines, reagents and consumables for COVID-19 testing.

(Source: National Health Laboratory Policy: 2013–2017)

The two main biomedical research institutions (University Medical Research Laboratories) in Ghana are Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR) in Accra and Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine (KCCR) in Kumasi. These two institutions are well-equipped and can perform various molecular diagnostic tests; they were the only testing sites readily available to perform SARS-CoV-2 testing in March 2020, when the first suspected COVID-19 sample presented at NMIMR. Testing capacity for SARS-CoV-2 at these institutions combined is approximately 3,800 tests per day: NMIMR has a testing capacity of approximately 3,000 tests per day, and KCCR has a capacity of approximately 800 tests per day (Appiah, Citation2020; Ghana, Citation2020; Nyabor, Citation2020). However, these facilities do not have the capacity to accommodate the testing needs of the entire country, which has a population of approximately 30 million, should Ghana experience a sudden increase in cases. NMIMR and KCCR experienced serious setbacks such as backlogs of samples, increased turn-around-times (>48 hours), shortages of reagents and essential consumables, shortages of and fatigue in skilled laboratory staff, a lack of safe pretesting storage space, compromised biosafety and biosecurity, equipment failures and service delays, and improper biohazardous waste management in the early stages of the pandemic. During the initial phases of COVID-19 emergence in the country, some specimens had to be transported for long distances and therefore long hours before reaching NMIMR and KCCR testing laboratories (Ama, Citation2020), which affected specimen integrity as the cold chain system (temperatures between 2–8°C) was compromised (Hanwell, Citation2020). These and other factors can affect the timeliness and accuracy of results with dire consequences. For example, in the town of Walewale in the North East Region of Ghana, a 21-year-old patient died of COVID-19 before the test results were received from KCCR, Kumasi, which is approximately 503 kilometres away (Yakubu, Citation2020). The patient was admitted to the Walewale Municipal Hospital on 6 April 2020, and presented with symptoms similar to COVID-19 (Tanko, Citation2020). Samples were collected and sent for testing the same day the patient was admitted but laboratory results did not become available until four days after admission (Ghanaweb, Citation2020a; PulseGhana, Citation2020; Tanko, Citation2020). Although the patient died two hours after admission, the delayed results may not have affected the patient’s outcome, but it might have had serious repercussions for the patient’s family members, residents of Walewale, and the healthcare workers who treated the patient. From a public health perspective, four days was too long to allow immediate and effective contact tracing, quarantine, and testing of all possible contacts, potentially resulting in further spread of the virus.

As part of the government’s effort to further increase testing capacity for the virus that causes COVID-19 in Ghana, NPHRL and Tamale PHL and Kumasi PHL, as well as other nonclinical laboratories such as the Veterinary Services Directorate (VSD) (Accra, Sekondi and Pong-Tamale), University of Health and Allied Sciences (Ho), and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) (Accra), were approved to conduct testing after successfully undergoing assessments, training, and quality assurance (QA) checks by NMIMR and KCCR. With these additions, testing capacity has increased by approximately 4,800 tests per day (Fred, Citation2020; GBC, Citation2020; GNA, Citation2020; GNA & Ghana News Agency, Citation2020). Laboratory testing capacity has further been expanded with the addition of other private sector laboratories to meet the testing demands during this current pandemic, as the number of cases and contacts increase (e.tvGhana, Citation2020; Fred, Citation2020).

Ghana currently has about 126 GeneXpert systems (Cepheid Inc) that are used for tuberculosis (TB) testing (Ghanaweb, Citation2020b). Currently, these GeneXpert platforms have been optimised in sixteen (16) hospitals for SARS-CoV-2 testing after appropriate system upgrades, risk assessments, and quality checks were completed. The Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 test (Cepheid) is well-suited to be a point-of-care (POC) test for pandemic response (Cepheid, Citation2020). The test cartridge includes all the necessary reagents to detect genetic information unique to the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Cepheid, Citation2020) in less than an hour. One important step in this particular test is loading the patient’s samples (nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab in saline) into the cartridge, which is primarily done inside Class II Biosafety Cabinets (BSCs) or glove boxes. One challenge faced by many laboratories in Ghana is the lack of these BSCs and minimal systems in place for annual certification or regular device maintenance. Although GeneXpert machines are available across the country, investments are needed to increase the number of certified BSCs along with implementing routine maintenance and certification to ensure the safety of laboratory scientists. With government’s intervention through the Ministry of Health, some health facilities have received glove boxes, which have similar functionality as BSCs, aiding them to test for SARS-CoV-2 with their GeneXpert system. When using existing GeneXpert machines for SARS-CoV-2 testing, the volume of TB testing could be disrupted and should also be considered (TheGlobalFund, Citation2020).

The need for testing data

As SARS-CoV-2 testing continues, rapid generation of accurate and reliable data are important to understand how the pandemic is progressing (Joe et al., Citation2020). Accurate and reliable data help emergency response teams respond appropriately to public health threats and help identify which countermeasures are effective (Joe et al., Citation2020). Testing data are needed to examine and compare health outcomes of individuals living in areas with a high prevalence of COVID-19 who received appropriate interventions. In recent years, Ghana has improved its process and timeliness of laboratory data reporting, yet there is more to do in terms of rapid testing leading to increased data generation for informed decisions (Christopher & Peter, Citation2020). The two major testing centres had substantial sample backlogs during the early phase of the pandemic (Dogbey, Citation2020; Ghanaweb, Citation2020c), which significantly slowed the pace of acquiring real-time laboratory data and this led to gaps in patient care and contact tracing. The number of confirmed cases is crucial for helping us understand the progression of the pandemic, all of which are solely based on laboratory testing. According to WHO, a confirmed case is ‘a person with laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 infection’ (WHO, Citation2020g). Real-time laboratory data are also helpful in disease modelling and predictions (Medicine, Citation2020; University, Citation2020). The timeliness of reporting laboratory data is also based on the use of robust data capture systems. Ghana has weak laboratory information management systems hence networking of data from different laboratories is quite difficult. To improve data reporting, Ghana introduced the Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS) to help in the rapid reporting of laboratory results from the PHLs, NMIMR, KCCR and Veterinary Laboratories. The system has further been expanded to include some private sector and other newly approved testing laboratories. However, inaccessibility to reliable and consistent internet connection makes the use of this system quite difficult.

Local scientific breakthroughs

Ghana has taken proactive measures to track the virus. Scientists at NMIMR and the West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP), both at the University of Ghana, have sequenced genomes of SARS-CoV-2 (WACCBIP, Citation2020). Sequence data have revealed important genetic information about the virus. The scientists sequenced RNA extracted from 15 samples from selected cases in Ghana to better understand the genetic differences of the virus circulating in the country. The samples were from travellers who arrived in Ghana from the United Kingdom (2), Norway (1), Hungary (1), India (1), and the United States (1), as well as nine samples from persons who had no history of travel and were likely infected through community transmission.

The data show that while there are some differences between the strains from the various countries, all the genomes have a resemblance (with >92% sequence similarity) to the strain isolated in Wuhan, China. The information from the sequence data has been shared with scientists around the world through an open access platform called the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) database, where other sequences from various countries are stored (WACCBIP, Citation2020). This information is vital for understanding the nature of the virus and how it is spreading. More recently, scientists in the country have identified new COVID-19 variants which had been reported in the UK and South Africa (Myjoyonline, Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

A team of scientists from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), in collaboration with Incas Diagnostics, a biotech company in Kumasi, Ghana, have developed a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) kit for testing COVID-19 IgM/IgG (KNUST, Citation2020). Currently this test is under evaluation by the Ghana Food and Drugs Authority. With this new technology, surveillance could be strengthened within the country, and data generated can be used to model the course of the pandemic.

Gaps in laboratory system in Ghana

Over the past decade, vertical programs such as the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), and the Global Fund have focused on developing laboratory capacity in Ghana. Quality management systems have been introduced by utilising Stepwise Laboratory Improvement Towards Accreditation (SLIPTA) and Strengthening Laboratory Management Towards Accreditation (SLMTA) in Ghana for HIV testing laboratories. There is no comprehensive approach for strengthening laboratory capacity. Testing laboratories continue to face various challenges that limit their ability to adequately respond to public health emergencies, as well as to routine clinical diagnostic testing. Under the IHR 2005 and Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), Ghana took part in WHO’s Joint External Evaluation (JEE) in 2017 and scored 2 of 5 possible points in biosafety and biosecurity and most of the National Laboratory System indicators, which is suggestive of a very weak laboratory system (WHO, Citation2020a). Likewise, Ghana’s internal assessment in 2016 highlighted various challenges, including the lack of a national laboratory policy (NLP), the lack of a national referral for routine clinical specimens, the lack of systematic reporting of priority diseases except those under surveillance, a limited budget for equipment, reagents, and supplies for detection of priority diseases, obsolete laboratory equipment, and an erratic supply of laboratory reagents (Ghana-Health-Service, Citation2016). NPHRL, which is part of the WHO Global Measles and Rubella Laboratory Network (GMRLN), has other challenges, such as inadequate financial resources for laboratory activities and maintenance of equipment and lack of political commitment (e.g. policies and budget) to support the laboratory (Ogee-Nwankwo et al., Citation2017).

The need for improved molecular diagnostics capacity in Ghana

Ghana’s fight against the virus that causes COVID-19 was supported by the availability and capacity of NMIMR and KCCR to test samples collected during the early phase of this pandemic. Because of these two facilities, Ghana was among the few African countries that conducted aggressive COVID-19 testing. This underscores the need for expanded molecular diagnostics for a swift, accurate, and timely response to COVID-19 and other possible outbreaks and pandemics. This expansion would also help stimulate a robust bioeconomy because the data can be used to improve the health of Ghanaians, as well as increase productivity through the implementation of data-driven and evidence-based policies. Improvements in molecular testing would help advance the knowledge base of laboratory scientists and also expand new frontiers of bioinformatics and data management. There is also a need to resource research and public health laboratories to be able to carry out more advanced techniques such as molecular sequencing to enable the country study the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 viruses.

Implementation of NLP will ensure the establishment of systems, processes, and procedures that will support laboratories across the tiers of the health delivery system in Ghana. Laboratories need both financial and political support at the highest level, without which these laboratories cannot be maintained and sustained. A lack of support will ultimately affect laboratories’ ability to routinely diagnose samples as well as adequately respond to outbreaks and pandemics (Ogee-Nwankwo et al., Citation2017). The government of Ghana intends to increase its efforts to enhance capacities of the existing laboratories while establishing new laboratories across every region and three infectious disease control centres in the three zones of Ghana: the Coastal, Middle-belt and Northern zones. All existing and new laboratories should incorporate capacity for molecular diagnostic testing to aid in quick and accurate detection of diseases. In addition, laboratory biosafety is essential to keep the laboratory workforce safe and ready to respond to any outbreak. In order to improve laboratory capacity and biosafety, funds should be set aside for procurement of reagents and testing supplies, establishment of an equipment and maintenance program, and for human resources needs. This would include a countrywide BSC certification program, and provision and maintenance of PPE stockpiles for laboratory staff. Laboratory data collection and analysis systems should be enhanced so that laboratories can improve test turn-around time, allowing for near real-time disease monitoring and response across all laboratories. Finally, maintaining qualified and adequate staff and implementation of a continuous education program will ensure that staff are well-trained to respond to this and future outbreaks.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed weaknesses in the diagnostic systems in many countries of the world. Over the past decade, programs such as PEPFAR, PMI, Seasonal Influenza Program, and GHSA have contributed greatly to the development of laboratory capacity in Ghana, but these are not adequate. Interventions such as SLIPTA and SLMTA, which aimed to develop holistic laboratory capacity through quality management systems, could not be sustained due to lack of cohesiveness, investment and commitment from the goverment. Laboratory capacity and time to response could be improved by committing to address the critical gaps, recommendations and priority areas noted in the JEE for Ghana’s laboratory systems. To prepare Ghana for the next outbreak or pandemic, priority should be given to all teaching hospital laboratories, regional hospital laboratories, the four PHLs, and research institutions such as NMIMR, KCCR, Kintampo, Navorongo, and Dodowa Health Research Centers, and subsequently expanding to all tiers of the laboratories.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ama, C., Health Service official calls for Covid-19 testing centre for the north. https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/national/health-service-official-calls-for-covid-19-testing-centre-for-the-north/ Accessed 21/ May/2020. 2020.

- Andy, H., What’s A ‘Reagent’ and why is it delaying expanded coronavirus testing? https://www.rferl.org/a/coronavirus-reagent-delaying-expanded-coronavirus-testing-/30563198.html Accessed 26/May/2020. 2020.

- Appiah, P., Kumasi centre for collaborative research re-strategising to expand testing capacity. https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/national/kumasi-centre-for-collaborative-research-re-strategising-to-expand-testing-capacity/ Accessed 06/ May/2020. 2020.

- Bostock, B., The coronavirus has now hit every continent except Antarctica after a man in Brazil tested positive. https://www.pulse.com.gh/bi/tech/the-coronavirus-has-now-hit-every-continent-except-antarctica-after-a-man-in-brazil/yr9lzt7 Accessed 19/May/2020. 2020.

- CDC, Information for clinicians on investigational therapeutics for patients with COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/therapeutic-options.html Accessed 19/May/2020a. 2020.

- CDC, Overview of Testing for SARS-CoV-2. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/testing-overview.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhcp%2Fclinical-criteria.html Accessed 30/June/2020b. 2020.

- CDC, Interim Guidelines for COVID-19 antibody testing. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antibody-tests-guidelines.html Accessed 30/June/2020c. 2020.

- Cepheid, Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 has received FDA emergency use authorization. A rapid, near-patient test for the detection of the 2019 novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. https://www.cepheid.com/coronavirus Accessed 06/May/2020.2020.

- Christopher, G., & Peter, M., Coronavirus: Are African countries struggling to increase testing? https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52478344 Accessed 16/May/2020. 2020.

- Corporation, Q., Sofia 2 SARS Antigen FIA. https://www.fda.gov/media/137885/download Accessed 26/May/2020. 2020.

- Dogbey, S.A., Kumasi centre for collaborative research has a backlog of 8000 samples to test – Virologist. https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/national/kumasi-centre-for-collaborative-research-has-a-backlog-of-8000-samples-to-test-virologist/ Accessed 01/ May/2020. 2020.

- DW, COVID hits Antarctica, the virus last untouched continent. https://www.dw.com/en/covid-hits-antarctica-the-virus-last-untouched-continent/a-56038377 Accessed 15/February/2021.2021.

- e.tvGhana, University of Ghana, Noguchi on Ghana’s test kits. https://www.etvghana.com/university-of-ghana-noguchi-on-ghanas-test-kits/ Accessed 25/April/2020.2020.

- ECDC, COVID-19 situation update worldwide, as of 18 Feb 2021. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases Accessed 18/February/2021. 2021.

- Fred, D., UHAS to begin COVID-19 testing – health minister. https://dailyguidenetwork.com/uhas-to-begin-covid-19-testing-health-minister/ Accessed 06/May/2020. 2020.

- GBC, CSIR assists with testing of Covid-19 cases. https://www.gbcghanaonline.com/news/csir-assists-with-testing-of-covid-19-cases/2020/ Accessed 06/May/2020. 2020.

- Ghana, U.O., Noguchi memorial institute for medical research receives donation from Zoomlion Ghana limited to support COVID-19 research. https://www.ug.edu.gh/news/noguchi-memorial-institute-medical-research-receives-donation-zoomlion-ghana-limited-support Accessed 06/May/2020.2020.

- Ghana-Health-Service. (2016). International health regulations (2005) self-assessment using Joint External Evaluation (JEE) tool GHANA. 1–41.

- Ghana-Health-Service, Ghana Health Service Organisational Structure. https://www.ghanahealthservice.org/ghs-subcategory.php?cid=&scid=43 Accessed 27/April/2020a. 2017.

- Ghana-Health-Service, COVID-19 Updates. https://ghanahealthservice.org/covid19/ Accessed 14/May/2020b. 2020.

- Ghanaweb, Private health facility in Walewale closed down after coronavirus death, contact tracing begins. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Private-health-facility-in-Walewale-closed-down-after-coronavirus-death-contact-tracing-begins-922339 Accessed 13/May/2020a.2020.

- Ghanaweb, Make functional GeneXpert machines to enhance COVID-19 testing – Lab scientists to gov’t. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Make-functional-GeneXpert-machines-to-enhance-COVID-19-testing-Lab-scientists-to-gov-t-944620 Accessed 13/May/2020b.2020.

- Ghanaweb, Coronavirus: Backlog samples to be cleared by Sunday – KCCR. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Coronavirus-Backlog-samples-to-be-cleared-by-Sunday-KCCR-939310 Accessed 01/May/2020c.2020.

- GNA, Ghana news agency. Vet Services Directorate ready for COVID-19 testing. https://www.businessghana.com/site/news/general/210204/Vet-Services-Directorate-ready-for-COVID-19-testing Accessed 06/May/2020. 2020.

- GNA, Ghana News Agency. Covid-19: Ghana to start daily testing May 7. https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/national/covid-19-ghana-to-start-daily-testing-may-7/ Accessed 06/May/2020. 2020.

- Hanwell, COVID-19 Test kit temperature monitoring. https://hanwell.com/news/covid-19-test-kit-temperature-monitoring/ Accessed 21/May/2020.2020.

- Hellewell, J., et al. (2020). Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. The Lancet Global Health, 8(4), e488-e496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7

- Hopkins, J., Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html Accessed 18/May/2020. 2020.

- Joe, H., et al., Coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing Accessed 15/May/2020. 2020.

- KNUST, KNUST and incas diagnostics develop rapid COVID-19 diagnostic test. https://www.knust.edu.gh/news/news-items/knust-and-incas-diagnostics-develop-rapid-covid-19-diagnostic-test Accessed 29/ April/2020. 2020.

- Medicine, L.S.O.H.A.T., Real-time analysis of COVID-19: Epidemiology, statistics and modelling in action. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/newsevents/events/real-time-analysis-covid-19-epidemiology-statistics-and-modelling-action Accessed 01/May/2020.2020.

- Myjoyonline, New Covid-19 variant detected in Ghana – Akufo Addo. https://www.myjoyonline.com/new-covid-19-variant-detected-in-ghana-akufo-addo/ Accessed 21/February/2021a.2021.

- Myjoyonline, Ghana records South African variant of Covid-19 – Africa CDC confirms. https://www.myjoyonline.com/ghana-records-south-african-variant-of-covid-19-africa-cdc-confirms/ Accessed 21/February/2021b.2021.

- Nyabor, J., Noguchi testing over 2,000 COVID19 samples daily. https://www.universnewsroom.com/news/noguchi-testing-over-2000-covid19-samples-daily/ Accessed 06/May/2020. 2020.

- Ogee-Nwankwo, A., et al. (2017). Assessment of national public health and reference laboratory, Accra, Ghana, within framework of global health security. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(13), S121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170372

- PulseGhana, 19-year-old boy dies of COVID-19 in Walewale. https://www.pulse.com.gh/news/local/19-year-old-boy-dies-of-covid-19-in-walewale/1hb28pg Accessed 13/May/2020.2020.

- Tanko, E., Walewale residents under self-quarantine after possible contact with Covid-19 victim. https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/walewale-residents-under-self-quarantine-after-possible-contact-with-covid-19-victim/ Accessed 13 May/2020. 2020.

- TheGlobalFund, COVID-19 information note: Considerations for global fund TB support. https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/9510/covid19_tuberculosis_infonote_en.pdf?u=637233410310000000 Accessed 06/May/2020.2020.

- TheLocal, ‘200,000 tests a day’: Germany pushes to expand coronavirus testing. https://www.thelocal.de/20200327/germany-pushes-to-expand-coronavirus-testing-capacity Accessed 15/April/2020.2020.

- UNICEF, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): What parents should know. https://www.unicef.org/ghana/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-what-parents-should-know Accessed 19/May/2020. 2020.

- University, C., Modelling transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 in China and US. http://www.columbia.edu/~sp3449/covid-19.html Accessed 01/ May/2020. 2020.

- WACCBIP, WACCBIP scientists sequence genomes of novel coronavirus. https://www.waccbip.org/waccbip-scientists-sequence-genomes-of-novel-coronavirus/ Accessed 29/April/2020. 2020.

- WHO, Joint external evaluation of IHR core capacities REPUBLIC OF GHANA. Mission report:6–10 February 2017. https://extranet.who.int/sph/sites/default/files/jeeta/WHO-WHE-CPI-2017.26-eng.pdf Accessed 01/June/2020a.2017.

- WHO, Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: Implications for IPC precaution recommendations. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations#:~:text=According%20to%20current%20evidence%2C,transmission%20was%20not%20reported. Accessed 19/May/2020b. 2020.

- WHO, Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses#:~:text=protect. Accessed 19/May/2020c. 2020.

- WHO, Key considerations for repatriation and quarantine of travellers in relation to the outbreak of novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV. https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/key-considerations-for-repatriation-and-quarantine-of-travellers-in-relation-to-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov Accessed 19/May/2020d. 2020.

- WHO, Laboratory testing strategy recommendations for COVID-19. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331509/WHO-COVID-19-lab_testing-2020.1-eng.pdf Accessed 28/April/2020e. 2020.

- WHO, Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected human cases. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331329/WHO-COVID-19-laboratory-2020.4-eng.pdf Accessed 15/April/2020f.2020.

- WHO, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)situation report –61. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200321-sitrep-61-covid-19.pdf Accessed 13/May/2020g.2020.

- WHO, WHO issues its first emergency use validation for a COVID-19 vaccine and emphasizes need for equitable global access. https://www.who.int/news/item/31-12-2020-who-issues-its-first-emergency-use-validation-for-a-covid-19-vaccine-and-emphasizes-need-for-equitable-global-access Accessed 12/February/2021. 2021.

- Yakubu, M., Private health facility in Walewale closed down after COVID-19 death, contact tracing begins. https://www.primenewsghana.com/general-news/private-health-facility-in-walewale-closed-down-after-covid-19-death-contact-tracing-begins.html Accessed 28/April/2020. 2020.