ABSTRACT

Social determinants of health are an important aspect of improving health outcomes. Militaries have deployed global health engagement activities to meet security objectives from peacetime through post-conflict. Two frameworks, the Social Model of Health and the U.S. Institute of Peace Strategic Framework for Stabilisation and Reconstruction, have similarities and are reviewed in this paper. Drawing similarities between the two presents opportunities for targeted, well-planned global health engagement activities that may bring stronger health outcomes. Military global health efforts must work with civil affairs experts and civilian partners within the host nation health context to target the most amenable social determinants of health elements that may enhance security and stability in that society.

Introduction

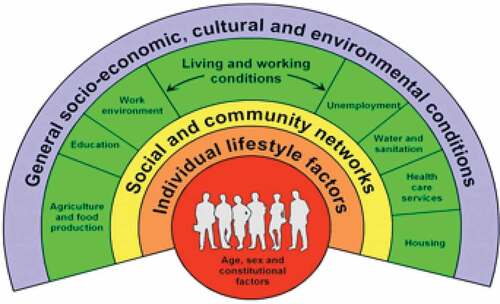

Social and environmental influences (the conditions in which people are born, live, work and age) greatly impact individual and population health (World Health Organization, Citation2008). There is a vast amount of evidence that socioeconomic and human behavioural factors can impact health outcomes. For example, ingestion of lead can stunt growth in children; air pollution can exacerbate asthma; and availability of alcohol can affect rates of alcohol-related injuries, and each of these examples is more pronounced in disadvantage neighbourhoods(Braveman & Gottlieb, Citation2014). While it is understood that social determinants of health (SDH), such as the social and economic factors, play a role in health equity, they are not always successfully factored into plans that improve health outcomes. Dahlgren and Whitehead identified the main determinants of health, originally in 1991 then updated in 2007 () shows a Social Model of Health in a simplified graphical manner with multiple layers that affect an individual’s health (Dahlgren & Whitehead, Citation2021). SDH helps to explain why a community exhibits certain health behaviours and identify potential root causes for disease and resulting health outcomes(World Health Organization, Citation2005). In order to have the whole picture, it is critical to have a view of all of the factors that directly or indirectly affect health, quality of health care, and quality of life.

Figure 1. The main determinants of health. Each layer shows the influences that can impact health, starting with a base layer of individuals with fixed set of genes and sociodemographic characteristics and expanding outward to structural factors. This illustration can be found at https://esrc.ukri.org/about-us/50-years-of-esrc/50-achievements/the-dahlgren-whitehead-rainbow/.

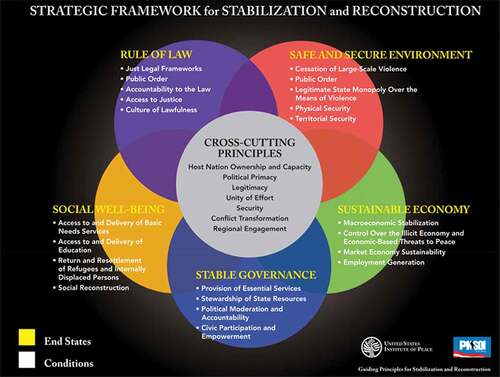

A similar set of economic and social factors are used when assessing the security and stability of a nation from a geopolitical perspective. Interestingly, if we look closely at a framework of essential elements for national stability, we see the SDH embedded as critical elements. Stability is dynamic but is defined as an ideal of governance where the state can provide essential services, serve as responsible steward of resources, and is voluntarily accountable to the population. This nexus of stability, security, and SDH emphasises the importance of applying global health engagement (GHE) and health diplomacy to sustainable outcomes; moreover, it supports the idea that the health of a population is essential to national stability. Considering this nexus of the SDH in the context of a stability framework is important for military GHE and civilian humanitarian global health activities. Stability and security that contribute to peace is a whole of government/whole of society effort and all health activities should be considered within this larger context.

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) advocating for governments to focus on SDH to achieve health equity (World Health Organization, Citation2008). The WHO stated, ‘Every aspect of government and the economy has the potential to affect health and health equity, finance, education, housing, employment, transportation, and health.’ (World Health Organization, Citation2005). However, most of these economic and social policies are not written with health in mind, but they end up impacting the population’s health (Rasanathan, Citation2018; World Health Organization, Citation2008). In both industrialised and developing countries, health inequity is a prominent problem and directly and indirectly contributes to national instability. Ultimately, efforts in the health sector are crucial to stability and function within a feedback loop of stability, security, and health, with health being a measurable outcome. Health, in the comprehensive definition, is a basic and essential human need, and if individuals and populations can trust in the ethical distribution of the opportunity for optimal health, then stability and security are enhanced. Health of individuals and populations can be measured quantitatively via numbers and percentages of the burden of disease, particularly preventable diseases and conditions. Health may also be measured qualitatively via data from surveys such as a population’s perspective on food or water security.

Many governments provide significant aid and support to partner nations in collaborative efforts to enhance security and stability for mutual benefit (Burkett & Perkins, Citation2016; Chretien, Citation2011; Cullison et al., Citation2016). This effort is complex and fluid with strong advances and ineffective efforts. Several frameworks and indices have been developed to guide efforts in the pursuit of stability, such as the U.S. Institute of Peace Strategic (USIP) Framework for Stabilisation and Reconstruction (United States Institute of Peace, Citation2009); (). As noted, through the lens of public health, the foundations for stability and security are closely connected to SDH. This should be intuitive since the comprehensive end state of security and stability is healthy and productive citizens. An ‘end state’ is the specific situation or set of requirements that define successful attainment of the strategic military or geopolitical mission objectives. Hence, for GHE activities to support stability and security, they must integrate and support partner nation health systems in their quest to positively impact SDH and more effectively bolster long-term development efforts (United States Aid for International Development, United States Department of State, Citation2021).

Figure 2. The strategic framework for stabilisation and reconstruction. The major endstates are depicted with the necessary conditions to achieve the endstate. This image emphasises the interdependence of each endstate and the cross-cutting principles are critical to support stabilisation and reconstruction efforts. Photo courtesy: USIP.

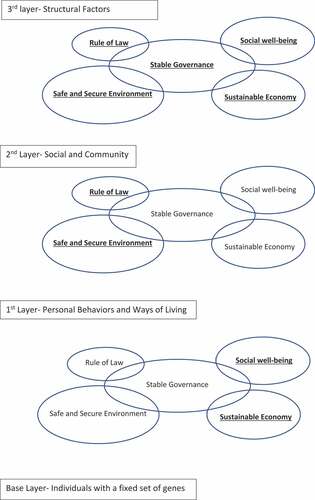

Different models for SDH and identifying the different factors or the ‘causes of causes’ exist with newer models building upon the older ones (Ansari et al., Citation2003; Braveman & Gottlieb, Citation2014; Healthy People, Citation2030; Marmot, Citation2007; Solar & Irwin, Citation2010; World Health Organization, Citation1986). The most recent framework includes the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) model developed by the WHO based on previous SDH models. The CSDH model adds a socioeconomic and political context that differs from others – identifying social and political mechanisms, such as the labour market, the educational system, and political institutions. One of the oldest frameworks was presented at the First International Conference on Health Promotion organised by the WHO (World Health Organization, Citation1986). The conference identified prerequisites for health: 1) peace; 2) shelter; 3) education; 4) food; 5) income; 6) a stable ecosystem; 7) sustainable resources; and 8) social justice and equity. The Healthy People Citation2030 recently identified similar domains of SDH: 1) Economic Stability; 2) Education Access and Quality; 3) Healthcare Access and Quality; 4) Neighbourhood and Built Environment; and 5) Social and Community Context (Healthy People, Citation2030). Healthy People Citation2030 also listed key issues within the five domains, such as access to health services, quality housing, and employment. One of the most useful SDH models is the Dahlgren-Whitehead ‘rainbow model’ (Dahlgren & Whitehead, Citation2021). When looking at the figure, individuals are at the centre with constant characteristics, such as age, gender, and their genetic makeup. Expanding outward are the influences on the individual’s health-personal lifestyle behaviours, such as smoking and physical activity; social and community influences; structural factors that can influence their health; and then the influences of the economy, cultural and environmental health prevalent in the population. Using the USIP Framework, we can match elements of different SDH models with principles of Stability and Reconstruction (). The different SDH models, the WHO model (World Health Organization, Citation1986); the Healthy People Citation2030 framework (Healthy People, Citation2030); and the Dahlgren-Whitehead Social Model of Health (Dahlgren & Whitehead, Citation2021) are referenced to show the comparability of the USIP Principles of Stability and Reconstruction across the evolving comprehensive SDH concept.

Table 1. Stability principles matched to social determinants of health

Health sector efforts alone cannot fix all the factors of stability because development requires a multidisciplinary, whole of society approach. However, there are areas of overlap between SDH and stability principles that present opportunity for targeted, well-planned activities that may result in stronger outcomes. Particularly, the Dahlgren-Whitehead Social Model of Health (DW Model) aligns best with the Principles of Stability and Reconstruction. Because the DW Model maps how the environment, cultural and structural influences an individual’s health, this model facilitates the USIP Guiding Principle End States, which aim to develop and change the outside influences of a population. Military global health efforts must work with civil affairs experts and civilian partners within the host nation health context to target the most amenable SDH elements that may enhance security and stability in that society. Accounting for the health context is to consider all domains of cultural – to include political, ethical, linguistic, religious, educational – at the national and local levels. Successful health activities and programmes, as well as other actions for stability, will not be sustained if they only include or validate outsider views. Local ownership is required, and programmes must integrate with or be built to achieve behavioural change, based upon the local concepts of health, health literacy, ethical activity, and existing ethnomedical systems that may be different from the perspective of the outsiders attempting to collaborate.

The WHO constitution states that ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity … The health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security and is dependent on the fullest co-operation of individuals and States.’ (World Health Organization, Citation1946). Public health/healthcare is an essential service and may be one of the most critical areas to engage when seeking solutions that increase stability. Adoption of full spectrum operations has been added to military doctrine to achieve stability and security and policy review reports that military personnel take on critical responsibilities of economic stabilisation and infrastructure in conflict zones. However, the author of that policy report found that these responsibilities have not been historically fully explained, including precision on support to SDH (Morrissey, Citation2015). Militaries must diligently develop global health practitioners who understand the integral role of SDH within stabilisation and reconstruction core concepts. Expert practitioners must then translate this concept into improved health activities that support security operations across all phases and ranges of military operations and are contributory to larger health sector goals.

Medical activities have the potential to have direct and indirect effects on stability in fragile states. In essences, fragility is the opposite of stability, thus a fragile state has a weakened central government, poor legitimacy for internal action and international engagement, and has challenges in providing basic public services. Any nation with any level of ongoing internal armed conflict has increased fragility. If planned and executed effectively, GHE aimed at societal infrastructure may decrease the probability of an escalated or sustained conflict. Health is a building block of stability with significant impact on the non-medical factors of stability and security. A host nation enhances legitimacy and trust of its population when it is seen to develop and sustain public health services aimed at the social and economic well-being of the population. ‘These programmes have inherent and profound benefits for civil society development.’ (United States Institute of Peace, Citation2009).

Socioeconomic policy and the physical and social environment in which people live and work impact health (World Health Organization, Citation2008). In turn, a population’s health directly affects their response to and influence upon government, policy, and productivity thus creating a cyclical relationship of stability, security, and health (Marrogi & Burkett, Citation2016). Attention to health sector infrastructure can bring about positive change in the intertwined factors that build a stable and productive society. Therefore, military GHE activities must target specific and attainable outcomes for host nation capabilities and capacities relevant to enhanced stability and security (Burkett et al., Citation2020; Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Citation2021). Whether GHE is conducted by a military or a civilian agency, plans must support the cultural context and legitimate local leadership for any short-term health engagement to have sustainable effects. For example, engagement that fosters dependence on external health providers and an emphasis on direct care rather than comprehensive, locally led health programmes may do more harm rather than good (Baxter & Beadling, Citation2013; Drifmeyer & Llewellyn, Citation2004a, Citation2004b; Moten et al., Citation2018).

Military operations include an agenda for stabilisation and capacity building to counter the expected destabilising effects of conflict (U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Citation2021). Short-term engagements in any sector of society will not achieve stabilisation, especially when local will and infrastructure is lacking. Military doctrine correctly focuses discussion of stabilisation efforts during post-conflict, reconstruction, and consolidation phases where countries are the least stable (U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Citation2021) and when local governmental and non-governmental capability may be minimal (Jones et al., Citation2006). Therefore, in addition, it is important to consider the peacetime shaping/prevention phase as a key to mitigating state failure if conflict and complex emergencies arise. Poverty, unemployment, political sidelining, and economic disparity are encountered in all countries, even countries deemed to be stable. However, in fragile states, these factors more readily hinder the country’s ability appease its population, potentially leading to conflict. Attention to health equity and quality through sustainable infrastructure inclusive of underserved subpopulations goes a long way to strengthen a positive health and security feedback loop.

Social determinants of health and stability framework

Bridging together models such as the USIP Strategic Framework for Stabilisation and Reconstruction (S&R) and the DW Model highlights challenges to placing global health practice within the context of overall stability and security. One challenge is to clearly align health context, desired health outcomes, and social determinants of health with critical stability factors for a given country. A second challenge is to then select, plan, and execute measurable health activities that achieve desired population effects and support stability end states.

Conceptually, the end states of the Strategic Framework for S&R align well with the three layers of the DW Model personal behaviour and ways of living, social and community, and the structural factors. Social, behavioural, and environmental determinants of health most easily equate with stability terminology and play a larger role in population wellbeing than biomedical and genetic factors alone (Taylor et al., Citation2016). Connecting social determinants of health with elements of the stability framework will help to identify country-specific desired health outcomes that determine selection and design of effective global health actions ().

Figure 3. Similarities between the strategic framework for stabilisation and reconstruction and the Dahlgren-Whitehead social model of health. Bolded titles indicate the most important endstates within its layer.

First, the concept of health and stabilisation connection is intuitive as ‘peace cannot be sustained over the long term without addressing the social well-being of a population’ (United States Institute of Peace, Citation2009). Social well-being involves meeting basic needs through equitable opportunity and long-term, sustainable development requires a foundation built upon access to water, food, shelter, health services, employment, and education that enables a peaceful and thriving life. Community conditions and work environments affect the social well-being of individuals. The WHO Commission on SDH (World Health Organization, Citation2008) calls for sustained action to achieve health equity across all governmental policies that affect the social well-being.

A second commonality between DW Model and the Strategic Framework for S&R is the stability principle of Rule of Law and the SDH labelled social justice and equity. The S&R Rule of Law end state is when the laws are consonant with international human rights norms and standards and are equally enforced among all individuals. Social justice and equity hold the same viewpoint that everyone should have equal opportunity and treatment that enables individual economic growth and success. The WHO Commission on SDH and the S&R Framework both recommend strengthening policy and action for equal rights and equitable access regardless of socioeconomic status or other. Health sector engagement programmes can be aimed to support rule of law and justice efforts and be congruent with security and stability principles.

A third parallel of the two models is between the stability end state requiring a safe and secure environment and the social determinant of health involving the neighbourhood and built environment. A safe and secure environment includes protections that steward clean air and land and allow human beings freedom for daily activities. The S&R framework includes physical and territorial security. Physical security allows the population to live with confidence in a minimal threat of attacks, while territorial security allows people and goods to move freely without fear of harm. One of the objectives of the Military Support to Stabilisation, Security, Transition, and Reconstruction Operations is to strengthen support to ‘… a fragile national government that is faltering due to serious internal challenges, which include civil unrest, insurgency, terrorism and factional conflicts.’ (Department of Defense, Citation2006). Military activities may help establish or re-establish safe, secure environments by working with governments and civilian organisations to create, rebuild and/or improve processes within the security, economic and political systems. Military civil and biomedical engineers can contribute to a safe environment by maintaining critical infrastructure and mitigate service disruption such as local water and sewer services, electrical service, educational opportunities, and access to medical care.

A fourth linkage is that the Stable Governance end state and health public policy SDH each emphasises the provision of essential services, and these should be given without discrimination by government officials. The WHO Commission on SDH stated that in order to improve daily living conditions, communities must have access to basic goods that promote well-being. Urban development and planning should promote provision of basic human needs and health equity in rural and urban areas. Full and fair employment and working conditions are essential and occupational health laws and rules can contribute by diminishing physical and psychosocial hazards. Policies relating to safe working conditions should be implemented to improve daily living. Preventive and Occupational medicine capabilities during military operations can be aimed to contribute to safe working and occupational health policies and activities.

Education and literacy development is a recognised SDH. Health literacy is naturally dependent on overall literacy as well as the cultural norms and traditions passed down locally. Ensuring outcome-based health literacy is critical for individuals to accept programmes and choose appropriate preventive and population-based protections. The misunderstanding of basic health information can deter individuals from seeking health services or living healthy lives, leading to chronic illnesses and disability. Although military efforts are focused on providing basic services, such as food, clean water, shelter and emergency medical treatment, health officials should also coordinate with partners to increase culturally relevant health literacy (Department of Defense, Citation2006) and maintain local quality educational services and equitable access.

The Sustainable Economy end state of stability includes employment generation as a condition that is consistent with employment as an SDH. Creating job opportunities builds a foundation for sustainable livelihoods. Military forces in conflict zones have helped plan and financially support a variety of businesses and development programmes to stimulate economies. The health sector can be an opportunity for creating sustainable jobs, and there is evidence of conflict and post-conflict successes training nurses, community health workers, and military medics. As with civilian global health efforts, these programmes are only sustainable if designed within the overall health sector context with local ownership.

A final connection to emphasise between DW Model and the Strategic Framework for S&R is the end state of Return and Resettlement of refugees and internally displaced persons compared with the water and sanitation SDH. Refugees displaced by war are the most vulnerable population and joint forces have a Geneva convention adopted mandate to care for them. The Guiding Principles states that refugees ‘have the option of a safe, voluntary, and dignified journey to their homes or to new resettlement communities; have recourse for property restitution or compensation; and receive reintegration and rehabilitation support to build their livelihoods and contribute to long-term development‘ (United States Institute of Peace, Citation2009). Public and preventive health personnel can help deliver immediate provision of basic necessities, such as food, water, and population hygiene until civilian refugee/displaced person expertise is fully engaged. Skilled local personnel can be supported to supplement aid delivery and maintain or re-establish basic water and sanitation that aligns to minimal standards for human sustainment and recovery such as Sphere handbook (Department of Defense, Citation2006; Sphere Association, Citation2018). Military veterinarians can also be of assistance to refugees by providing care and strategies for sustaining livestock (Department of Defense, Citation2006).

Unfortunately, some of the biggest challenges when dealing with social determinants include lack of agreement within a government or population on a vision for health, aiming for health equity even for the most vulnerable populations, difficulty in measuring important outcomes, and sustaining a path once details and ideas are agreed upon. Authorities and decision makers may lose motivation or be misdirected from the population’s needs after disruptive events, and this will also hinder the process of sustained focus. When the military is involved in a conflict, post-conflict reconstruction, or a complex emergency ground-level daily events make it challenging to maintain the connection of stability-supporting health outcomes if these are not well planned for in advance with local owners and partners.

Waiting to consider the health aspects of stabilisation operations post conflict will miss vital opportunities to prevent ongoing conflict or crisis. Maslow’s theory on hierarchy of human needs also notes that human security, including health and basic sustenance security, are critical before addressing other grievances. ‘Without basic necessities … large scale social instability will persist because people will be unable to resume the function of normal life- such as being able to sustain a stable livelihood, engaging in the community, and attending school.’ (United States Institute of Peace, Citation2009). Attention to SDH in peace and peacekeeping operations may bolster population positivity and productivity, deter conflict, and be keys to preventing a fragile state from tipping to further instability. Stabilisation is challenging and complex no matter at which phase of the operation it is being worked. Small teams created specifically to address and catalyse building local, culturally relevant, health sector capability and capacity (Burkett, Citation2012) may be the most effective tool to achieve overall strategies. Such small teams can be tailored to the needs of the partner nation, the local health sector, and synchronised with efforts in other sectors consistent with the multidisciplinary approach required for S&R.

Health system strengthening and the benefits beyond the health of the population

Typically, the first sectors to take a hit when there is conflict are social well-being and the health sector. The challenges that national and community institutions struggle with during peacetime are multiplied in conflict and crisis hindering efforts to meet the humanitarian needs of their people (U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Citation2021). Unfortunately, crucial public services dependent upon governance and security, are often the first services to collapse during conflict. When health systems and facilities are unable to function appropriately due to a compromised safe and secure environment, health is directly and indirectly affected (Jones et al., Citation2006). As stated by Martin, Grant, and D’Agostino (Martin et al., Citation2012), ‘To divert public spending in poor countries from health with the belief that if these nations become prosperous their health problem will take care of themselves, is a mistake’. Promoting and supporting locally owned capability building projects help the health sector and society as a whole. In other words, if the government is able to deliver essential services to meet basic human needs, then in turn social well-being is enhanced and other end states as aforementioned are enabled for greater success.

Health improvements lead to increase wealth and poverty reduction in at least four ways: 1) Healthier populations are more economically productive; 2) Proactive healthcare leads to decrease in many of additive healthcare costs associated with preventable trauma and disease and morbidity; 3) Improved health and quality of life represents a real economic, developmental, and psychological outcome itself and; 4) Spending on health promotion and disease prevention capitalises on the Keynesian economic multiplier and is a ‘major engine of economic growth’ (Martin et al., Citation2012).

This is not to say that the health sector is the only crucial sector for stability, it is to say that social determinants affecting individual and population health must be addressed to achieve gains within a whole stabilisation effort as laid out in the S&R framework.

It is important to illuminate the need for military global health engagement activities to consider social determinants of health in the context of multidisciplinary military stabilisation and reconstruction efforts. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) plan for health system strengthening (HSS; U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Citation2021) includes factors that interconnect with the health system, such as the public and private sectors and mirrors a combination of the S&R framework and the SDH. By investing in HSS, this allows for the country to take ownership and ramp up solutions to promote efficiencies in their own investment efforts(USAID, Citation2015). The country can sustain their efforts on health without needing short-term interventions from other nations. Overall, this leads the population to support the legitimacy of their own governments and ultimately focus on sustainable economic growth. Efforts need to consider the human resources for the health sector, health finance, health governance, and health information to achieve long-term positive outcomes (Roche et al., Citation2017).

Global health engagement activities conducted by militaries should adopt and mirror these health system strengthening principles whenever possible. DoD efforts may be more episodic, short-term, and more current-operation focused than USAID long-term development plans. However, these efforts, in most situations, can also be planned to catalyse and support long-term health impact and a whole-of-government approach. ‘Missed opportunities to invest in cost-effective measures to combat disease at a population level should therefore be recognized as a major threat to health and development in general.’ (Martin et al., Citation2012). Strengthening health systems may initiate or influence true stability. GHE activities that consider this interplay of stability framework elements and social determinants of health have the potential to affect necessary sectors directly and indirectly for a safe and secure environment, stable governance, rule of law, a stable economy, and thus lower the risks for state fragility (The Fund for Peace, Citation2021).

If stability is a return on investment, then investment in the health sector of a country with an eye on the SDH is paramount for militaries involved in operations from peacekeeping to full conflict. It is not coincidental that fragile states and countries in midst of conflict or complex emergencies have poor health data. Extended conflict or complex emergencies may stress any country and interrupt services and health reporting. Military health professionals must be able to integrate the tenets of sound and ethical health sector efforts with the end states needed for stability and security.

Conclusion

The concept comparison of the social ecological theory of health and the strategic framework for stabilisation and reconstruction may be intuitive to many working in global health and development. However, connecting the two and putting it into practice has not been incorporated into operational planning for global health engagement activities. Both the S&R framework and SDH are complex, systems-within-systems models. Effective GHE that supports joint operations in peacetime or conflict must consider how the health sector contributes to, and is impacted by, local governance, power imbalances, ethical considerations, resource disparities and injustices, and social determinants that affect stability (Melby et al., Citation2016). Much work is needed to further determine how to achieve this integration of SDH and Stability and could include retrospective case studies of different types of operations in different countries. Analysis could propose whether stability operations leveraged the social determinants concepts in this integrated manner and whether health planners intentionally tied strongly to stability principles. Similar prospective analysis during future operations will be additionally valuable.

The role of DoD GHE is not to specifically deliver a partner nation or local area of operations from poverty, unemployment, and to produce economic equality. These issues are a part of a greater issue of stabilisation and geopolitical objectives. However, the health context of each of these social issues must be appropriately considered within the intent of each mission. Global involvement of military forces in peacekeeping, conflict, and complex emergencies has generated a stabilisation framework. Not coincidentally, the SDH that are essential to human security nest well, in fact are interchangeable, within the key principles of this stabilisation framework. Utilising health outcomes and understanding the causes of instability should be envisioned in any part of a campaign; noting the similarities between the Strategic Framework for S&R and the DW Model are just the beginning of a process to enhance security and mitigate conflict ‘through prosperity rather than military conquest’ (Morrissey, Citation2015). Likely, optimising the security, stability, health continuum is best to take place during peace-time; however, when militaries are involved, it is imperative to embed SDH thinking into any health sector activity. Medical and non-medical, governmental and non-governmental personnel should understand and accept this nexus of health, security, and stability to appropriately select, design, and incorporate health capabilities for optimal impact.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Col Ramey Wilson for providing his insight and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Diana L. Aguirre

Diana L. Aguirre, MPH, was previously a research associate for the Embedded Health Engagement Team research programme. She has a B.S. in Public Health from Schreiner University, Texas, and a Master of Public Health in Epidemiology from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Texas. She is currently working on her Doctor of Public Health in Community Health Behavior and Education. Her research interests are in global health, health disparities and equity, and health systems.

Casey Perez

Casey Perez, MS, is the research associate for the Embedded Health Engagement Team research program. She has a B.S. in Biology from Texas Tech University, Texas and a Master of Science in Health and Kinesiology from the University of Texas at San Antonio, Texas. She has three years of experience in program evaluation and identifying social determinants of health that impact historically marginalised communities in San Antonio, TX.

Edwin K. Burkett

Edwin K. Burkett, MD, MBA, Col, USAF (Retired), is the course director for Medical Anthropology at the Uniformed Services of the Health Sciences and the Primary Investigator for the Embedded Health Engagement Team research program. He holds a M.D. from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, and completed his Family Medicine residency at Malcolm Grow USAF Medical Center. He also earned his M.B.A. in Strategic Leadership. During his career, Dr. Burkett served as the Director of the Defense Institute for Medical Operations; Chief of Global Health in the U.S. Joint Forces Command and for Air Combat Command; Family Physician/Flight Surgeon; and Air Force International Health Specialist.

References

- Ansari, Z., Carson, N.J., Ackland, M.J., Vaughan, L., & Serraglio, A. (2003). A public health model of the social determinants of health. Soz Praventivmed, 48(4), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-003-2052-4

- Baxter, M., & Beadling, C.C. (2013). A review of the role of the U.S. military in nonemergency health engagement. Mil Med, 178(11), 1231–1240. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00014

- Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep, 129(1_suppl2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291s206

- Burkett, E.K. (2012, March). Foreign health sector capacity building and the U.S. military. Mil Med, 177 (3), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-11-00087. PMID: 22479917.

- Burkett, E.K., Neese, B., & Lawrence, C.Y. (2020). Developing the prototype embedded health engagement team. Military Medicine, 185(Suppl._1), 549–553. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz207

- Burkett, E.K., & Perkins, D. (2016). U.S. National strategies and DoD global health engagement. Mil Med, 181(6), 507–508. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00021

- Chretien, J.-P. (2011). US military global health engagement since 9/11: Seeking stability through health. Glob Heal Gov, 4(2), 1–12.

- Cullison, T.R., Beadling, C.W., & Erickson, E. (2016). Global health engagement: A military medicine core competency. JFQ, 1st Qtr 2016(80), 54–61. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/JFQ/Joint-Force-Quarterly-80/Article/643102/global-health-engagement-a-military-medicine-core-competency/

- Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. Policies and strategies to promote equity in health. Institute for Futures Studies. Originally1991, Updated 2007. (Retrieved Nov 28, 2021) from http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/187797/GoeranD_Policies_and_strategies_to_promote_social_equity_in_health.pdf?sequence=1oratttps://www.iffs.se/media/1326/20080109110739filmZ8UVQv2wQFShMRF6cuT.pdf

- Department of Defense. 2006. Military support to stabilization, security, transition, and reconstruction operations joint operating concept. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/concepts/joc_sstro.pdf?ver=2017-12-28-162022-680#:~:text=The%20purpose%20of%20the%20Military,military%20support%20for%20stabilization%2C%20security%2C

- Drifmeyer, J., & Llewellyn, C. (2004a). Military training and humanitarian and civic assistance. Mil Med, 169(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED.169.1.23

- Drifmeyer, J., & Llewellyn, C. (2004b). Toward more effective humanitarian assistance. Mil Med, 169(3), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED.169.3.161

- The Fund for Peace. Fragile states index annual report 2020, 2020. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from www.fundforpeace.org

- Healthy People 2030. Social Determinants of Health Literature Summaries. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries

- Jones, S.G., Hilborne, L.H., Anthony, C. Ross, Davis, Lois M., Girosii, Federico, Bernard, Cheryl, Swanger, Rachel M., Garten, Anita Datar, Timilsina, Anga R., et al. 2006. Securing health: Lessons from nation-building missions. RAND Corporation, (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG321.html.2006

- Marmot, M. (2007). Achieving health equity: From root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet, 370(9593), 1153–1163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3

- Marrogi, A.J., & Burkett, E.K. (2016). Global health, concepts, and engagements: Significant enhancer for U.S. security and international diplomacy. JFQ, 1st Quarter 2016(80), 35–36. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/JFQ/Joint-Force-Quarterly-80/Article/643091/global-health-concepts-and-engagements-significant-enhancer-for-us-security-and/

- Martin, G., Grant, A., D’Agostino, M., Hardiman, M.C., & Wilson, K. (2012). Global health funding and economic development. Global Health, 8(8), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-8-8

- Melby, M.K., Loh, L.C., Evert, J., Prater, C., Lin, H., & Khan, O.A. (2016). Beyond medical “missions” to impact-driven short-term experiences in global health (STEGHs): Ethical principles to optimize community benefit and learner experience. Acad Med, 91(5), 633–638. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001009

- Morrissey, J. (2015). Securitizing instability: The US military and full spectrum operations. Environ Plan D Soc Sp, 33(4), 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1068/D14033P

- Moten, A., Schafer, D., & Burkett, E.K. (2018). Global health engagement and the department of defense as a vehicle for security and sustainable global health. Mil Med, 183(1–2), 14–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usx044

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy. DOD Instruction 2000.30, 2017. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/200030_dodi_2017.pdf

- Rasanathan, K. (2018). 10 years after the commission on social determinants of health: Social injustice is still killing on a grand scale. Lancet, 392(10154), 1176–1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32069-5

- Roche, S.D., Ketheeswaran, P., & Wirtz, V.J. (2017). International short-term medical missions: A systematic review of recommended practices. Int J Public Health, 62(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0889-6

- Solar, O., & Irwin, A. 2010. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf

- Sphere Association. 2018. The sphere handbook: Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. 4th Practical Action Publishing. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://www.spherestandards.org/handbook/

- Taylor, L.A., Tan, A.X., Coyle, C.E., Ndumele, C., Rogan, E., Canavan, M., Curry, L.A., & Bradley, E.H. (2016). Leveraging the social determinants of health: What works? PLoS One, 11(8), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160217

- United States Aid for International Development, United States Department of State. U.S. department of State and U.S. Agency for international development joint strategic plan fiscal year 2018-2022, 2018. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.usaid.gov/results-and-data/planning

- United States Institute of Peace. Strategic framework for stabilization and reconstruction. Guiding Principles for Stability and Reconstruction, 2009. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.usip.org/strategic-framework-stabilization-and-reconstruction

- U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Joint publication 3-07 stability. https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_07.pdf (accessed May 11, 2021)

- USAID. USAID’s vision for health systems strengthening 2015–2019, 2015. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-systems-innovation/health-systems/about

- World Health Organization. 1946. Constitution, (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution

- World Health Organization. 1986. First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference

- World Health Organization. 2005. Backgrounder 3: Key concepts. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/key_concepts_en.pdf

- World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: The WHO report on social determinants of health, 2008. (Retrieved May 11, 2021) from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1