ABSTRACT

Western nations ultimately rely for all aspects of their security and survival upon the natural, non-human world, yet they are currently degrading and depleting it to an extreme and potentially terminal extent. Recognizing this security paradox, scholars and policymakers have, in recent years, begun to renew and expand upon the West’s decades-old uneasy acknowledgement of the national security relevance of global anthropogenic environmental decline. However, important gaps in this renewed discourse remain. Approaches rooted in environmental science and environmental studies tend to frame the problem in simple biophysical terms instead of using the political and power frames of reference of actual states. On the other main side of the renewed discourse, Western national security apparatuses themselves (and their adjacent expert communities) have adopted a problematic neo-traditional approach, focusing on predicting which new strategic conditions and threats global environmental decline will generate, and how a largely status quo, intact state should prepare to respond to these conditions. This side of the renewed discourse arguably grossly underestimates environmental decline’s truly radical potential to destabilise the domestic state as well as external powers, and also avoids the central problem that a key origin of this decline is mundane Western state behaviour. This paper aims to introduce two new elements into Western national security community approaches to global environmental decline. First, I introduce a new way of defining organic national security and suggest why this may be a useful concept in evaluating and pursuing national security in the 21st century. Second, I lay out how re-attaining a modicum of organic national security will require that the West first reappraise its own contemporary embrace and normalisation of severe anthropogenic environmental degradation, contamination, and vanishing (SEDCOV) across nearly every policy domain.

Introduction

Despite being replete with environmental scientific expertise, the wealthy, relatively stable and democratic states of the global North, and more specifically the ‘West’, are on an accelerating course to deplete nature much faster than it can regenerate itself, including via depletion and consumption accomplished by extracting natural goods and resources from states in the global South (Hickel et al., Citation2022; Michael et al., Citation2012; United Nations [UN], Citation2019). The West’s ways of inhabiting the living world through a thick (and growing ever-thicker) layer of technologies and consumption practices based on cheap and free-flowing oil are usually equated, at least by the dominant centres of power in the state itself, with stability, prosperity, and security. But this oil-dependent paradigm for running states and for keeping citizens content and ostensibly secure comes at a great and ultimately unpayable price. Many scientists speak now of a human-caused sixth mass extinction already underway (e.g., Schoonover et al., Citation2021, p. 6) which is threatening not just the viability of thousands of non-human species themselves, but the collapse of the Earth’s complex web of life as we know and rely upon it, therefore potentially ending the human species too (W. Rees, Citation2017; Ripple et al., Citation2017; Swing et al., Citation2022). Large-scale environmental decline is increasing both at home and abroad, across numerous indicators, not limited to biodiversity loss linked with the displacement and harvesting by humans of so many other species (Maxwell et al., Citation2016), but also including things such as declining topsoil health and ocean health, plastics' and chemicals' contamination of the entire ecosphere, anthropogenic climate change and rising global average temperature, and damage to groundwater supplies and purity, to name only a few (Bradshaw et al., Citation2021; Gerardo et al., Citation2015; IPBES, Citation2019; Newbold et al., Citation2015; W. Rees, Citation2017). Global South countries, as well as countries arguably falling in between North and South designations, such as China and the oil-producing Gulf states, are also exacting significant tolls on the environment in their own modes and through their own pathways; however this paper will focus on Western nation-states.

The West is already deeply enmeshed in a novel security paradox: while Western states ultimately rely for all aspects of their security and survival upon a natural, non-human world which they did not create and have no means of replacing, they themselves are at the same time currently embracing a path of normalised degradation and depletion of this same non-human world and its web of life to an extreme and potentially terminal extent. Partly under the impetus of the 2015 United Nations Paris Agreement on climate change, a framework which has (if it has achieved little else tangible to date) helped bring climate scientists and the globe’s political and military leaders into increased conversation, Western security communities alongside peers and partners from environmental studies and environmental science have recently begun to renew their engagement with the West’s longstanding, if uneasy, acknowledgement that global environmental decline, including climate change, has security ramifications for the state which must be confronted. National security discourse has once again veered towards environmental topics, while environmental scientists and adjacent scholars have increasingly sought to elaborate on the security implications of their findings.

But while both scientists and national security communities consider themselves realists skilled in looking at hard external truths – the national security view honed by decades of trying to understand and predict risks and dangers in the anarchic international system of potential rivals in the age of WMD, and the conservation science view steeped in awareness of the long history of our planet, its laws of nature and complete indifference to human fates, the extraordinarily high species extinction rate over the past 3.5 billion years (Schoonover et al., Citation2021, p. 107), and so forth – these two communities remain rooted in, and apply, very different categories and frames of reference.

This may be why, despite the avowed interdisciplinarity of the discourse on the environment and security, it has tended to pool around two quite different centres of gravity: the scientist’s view, which focuses on the biophysical reality unfolding, and represents the state and its increasing security risks at a very high level of abstraction almost to the point of reducing them to ciphers or place-holders; and the security practitioner’s view, which is somewhat minimising and reactive regarding the environmental reality which is upon us, and regarding where and how appropriate responses to this reality must actually be developed. Scientists’ concerns have led them to call for states to pursue ‘transformational’ political and social changes to avoid causing the extinction of many inhabitant species of our biosphere including Homo sapiens (Bradshaw et al., Citation2021; Díaz et al., Citation2019; Herrington, Citation2020; IPCC, Citation2023; Ripple et al., Citation2017). The security approaches, meanwhile, focus on things like environmental decline’s foreseeable direct impacts on rivals or on the global South, and follow-on indirect security ramifications for Western states which may follow from these impacts. Such approaches largely avoid grappling with the more radical or internal dimensions of the West’s security paradox with regard to the natural world.

Proposals that states need to think about ‘ecological security’ put forward by Schoonover and others (e.g. MacDonald, Citation2018; Schoonover & Smith, Citation2023) are a good example of the first centre of gravity in this renewed discourse: conservation science-based approaches to our environmental quandary in the early 21st century which increasingly try to broach or bring in questions of state security and viability. Ecological security frameworks emphasise that the only real security is biological in its essence and foundation, discussing all the things which have to happen within the Earth’s natural systems to make life possible for human societies, and how easily human interference in these states of affairs can destabilise life for all species, including human beings, and thus states as well.

While convincing as a descriptive account grounded in detailed science, the power- or policy-relevant content of this approach (and other, similar approaches rooted in the sciences and reaching across to connect with the realm of security) appears indirect and somewhat limited. Approaches rooted in the natural sciences tend to be so physically oriented that all the human meanings that explain why states act as they do get stripped away. Even when (Schoonover & Smith, Citation2023) the effort is made to consider potentially risky biological changes in ecosystems (due to anthropogenic impacts) as leading to political, economic, and social impetuses which must confront the state, this usually comes at the end, rather than the beginning, of the framing, and the perspective remains distant from considering current and possible Western state actions vis-à-vis the environment and security from within the power and policy frameworks which bind these states.

These same tendencies to paint descriptive, natural laws-based pictures of states’ contemporary (and potential future) environmental insecurity also seem to have seeped into some of the approaches being taken within the other main vein of environmental security discourse, the one rooted in the study and practice of national security – but now also reaching out to try to incorporate some of the recent alarming scientific findings on human-caused global environmental decline. Hough (Citation2021) argues that contemporary menaces such as pollution, biodiversity decline, and climate change mesh better with discussing a broader, less state-based type of security, i.e. ‘human security’ more generally. He takes an approach more akin to a health sciences perspective on human safety and survival than a political and power-oriented one (Hough, Citation2005, Citation2021). And while Dalby, also writing as a political scientist, does maintain (in slight contrast to Hough) that international relations and security studies are a suitable home for thinking through environmental decline issues in new ways, given ‘international relations’ concerns with security and survival’ (Dalby, Citation2022, p. 33), he too falls into a more sciences-infused, abstraction-prone mode in his recent work. He equates environmental insecurity with fossil fuels’ use alone, claims to be able to include fossil fuel combustion in the military category of ‘firepower’, then reasons that since militaries (or states) have learned to limit, or not max out, nuclear weaponry’s potential firepower, for the sake of avoiding global environmental catastrophe, so too, he hopes, could states learn to limit combustion of fossil fuels and protect life on earth in this case as well (Dalby, Citation2022). Since fossil fuels’ use fits into the military firepower category only in a very physics-based sense, this limits the real-world utility of his conceptualisation. For actual states in the West, nuclear weapons (and other powerful weapons) are not normalised or integrated into daily life; nuclear weapons have long been subject of a ‘taboo’ prohibiting use (Tannenwald, Citation1999) (though of course stocking the planet with these arsenals remains full of risk). Fossil fuels’ combustion, on the other hand, is deeply normalised and celebrated, and integrated, often invisibly and as an assumed norm and expectation, into everyday economic, social, and defence and security policies and postures.

Aside from writers like Dalby and Hough, who are perhaps trying to extend the boundaries of this second centre of gravity in the environmental security discourse, at the core of this second side of the discourse we find the national security community (and its adjacent experts) focused primarily on climate security/insecurity, and secondarily on environmental degradation-linked security issues (Director of National Intelligence (DNI, Citation2023, p. 22–23), largely using a fairly neo-traditional approach. These dominant approaches to the discourse (to which both Dalby and Hough seem to be trying to respond) appear prone to reduce environmental decline’s security significance solely to the new strategic conditions and/or threats which climate change (and to some extent environmental degradation) will generate for other states, particularly geopolitical rivals such as Russia and China, as well as developing states throughout the global South, and then, in turn, via these other countries’ (and their people’s) foreseeable reactions and responses, for the West. This more pragmatic, military-linked discourse tends not to look within the Western state for environmental decline’s drivers, and usually fails to consider whether framing climate change and environmental degradation mostly as looming triggers for familiar kinds of risks and threats may mask a larger, even more dangerous environmental security paradox confronting the state.

This side of the environmental security discussion seems to have inherited a security studies approach which, since at least the 1990s, has been examining the ‘links from processes of environmental degradation to deterioration in security positions’ (Levy, Citation1995, p. 36). With its willingness to take ‘processes of environmental degradation’ as an unquestioned reality and starting point, this part of the discourse positions itself as essentially reactive. The focus is on anticipating spinoff threats from climate change and environmental degradation (Director of National Intelligence [DNI], Citation2023, p. 22–23), not on halting climate change or environmental decline themselves. The general focus is on, as Dalby pointed out was problematic in 2009 and 2013, ‘political instabilities in peripheral areas, and the possible spillover effects these may have for metropolitan societies’, such as how ‘[e]nvironmental shortages “there” may cause disruptions, wars and migration that will cause security concerns “here”’, giving ‘peripheral symptoms … attention rather than the metropolitan causes of climate change’ (Dalby, Citation2013, p. 41–42; Dalby, Citation2009; cf. also; Dalby, Citation2022, p. 24). These approaches still seem to adopt Levy’s 1995 assertion that the only realistic path open to states in light of global environmental decline is to muddle through with a ‘combination of prevention, adaptation, and “letting nature take its course”,’ since ‘to “roll back” global environmental change is forbiddingly costly’ (Levy, Citation1995, p. 36). In today’s parlance the preferred posture is usually referred to as pursuing (again, usually only ‘climate’ rather than full environmental) mitigation, adaptation, and resilience, while continuing to assist the global South with ‘development’, but now in a ‘sustainable development’ mode (a goal frequently articulated by the United Nations and shared by other multilateral institutions as well as some global South governments). Employing various carbon capture and storage technologies, shifting to decarbonized, ‘renewable’ energy sources, or helping to protect carbon sinks such as forests, peatlands, and oceans from further degradation, are among the most ambitious mitigation strategies, both at home and as projects sponsored in and ‘for’ the South. Smaller-scale adaptation and mitigation proposals often boil down to basic things such as making changes to existing built forms or future building practices, or restoring natural buffer zones of various kinds to heat- or flood-prone areas (see, e.g., IPCC, Citation2023; or US federal agency guidelines at https://toolkit.climate.gov/). The possibility of truly ‘rolling back’ anthropogenic global environmental change as a whole, which is what the scientific evidence suggests is urgently needed, is nowhere in evidence. And supporting such mitigation, adaptation, and resilience measures at home and globally is mostly portrayed, again, as serving the West’s national security interest not because of the direct threats environmental degradation and climate change pose to the West itself, but because the security community perceives that global environmental degradation and climate change could lead to an array of follow-on threats such as enormous upticks in mass migration, political instability in the global South, destabilising agricultural pressures, a rise in extremism, and so on (Al-Marashi & Causevic, Citation2020; Busby, Citation2022; DNI, Citation2023; Leddy, Citation2020; Schaik et al., Citation2020, and others in that Special Issue; Wallace, Citation2018). Little discussion is held here of environmental degradation simpliciter as a (potentially existentially) threatening behavior by the West toward others and/or toward itself.Footnote1 Overall, such approaches arguably grossly underestimate the severity of the anthropogenic environmental decline that has already happened (and seems poised to continue and worsen) and what it spells for the West itself, while also avoiding the central problem that a key origin of this decline is mundane Western state behaviour.

Arguably it is important for normative, survival-oriented reasons to not simply leave the discourse on the environment and Western states’ security in this largely bifurcated and unsatisfying condition: the scientifically-framed end of the environmental security discourse too reductive, biophysical, and merely descriptive to be immediately useful to real states (Snow, Citation2023), and the more military or pragmatic end of the discourse too narrow, reactive and superficial (Thomas, Citation1997) in its appreciation of the scope of the security challenges which have arrived as a result of human-caused environmental change (Snow, Citation2023), including the extent to which such challenges are of a radically internal type in terms of both their origin and their sphere of direct impact. In the remainder of this paper, I would like to introduce two new intertwined elements potentially useful in Western national security community approaches to global environmental decline, which might form a contribution to more fully articulating the West's current environmental security paradox.

First, I introduce a new way of defining organic national security (Snow, Citation2023) and suggest why it may be a useful concept in evaluating and pursuing national security in the 21st century. The organic national security frame departs from the status quo in part; it does not downplay or falsely externalise global environmental decline’s security significance for the West. Yet it also builds on existing state approaches to national security and seeks to avoid the scientists’ common problem of idealizing human decision-makers as free from power and political constraints.

Second, I lay out how the organic national security concept helps justify, and support, the reappraisal of Western states' contemporary embrace and normalisation of severe anthropogenic environmental degradation, contamination, and vanishing (SEDCOV) across nearly every policy domain. SEDCOV originating (in various ways) in the West has driven, and continues to drive, rapid global environmental decline, and this is the heart of the West’s environmental security dilemma. SEDCOV, as a qualitative, security-relevant notion, could potentially function as a key term in the new national security lexicon which seems required for assessing matters of organic national security. ‘Does decision, policy, or posture X entail SEDCOV?’ would be a simple question to ask about any and all of the state’s own decisions or policies – no matter which policy basket they technically fell into. (Whether nominally economic, social, defense, housing, financial, trade, education, transportation, or any other type of policy, most of what the state does is inherently ‘environmental’ in its direct impacts.) This questioning or surveying thought process could begin to help shape new perspectives on the inherent risk or danger associated with various mundane state policies and positions, even while most SEDCOV-entailing policies could not be halted overnight but would have to be phased out on a prioritised basis over time.

The environmental security situation in which the West finds itself today-- mostly as the aggregate result of its own actions, inventions, and choices in pursuing and setting up the global oil-based economy and its concomitant technologies and industries – is complex, novel, and potentially deeply destabilising. The state’s ability to navigate such waters is far from proven (Snow, Citation2023). But one knowable aspect of this security dilemma itself is that the West’s embrace and normalisation of SEDCOV at the national and global scale is what has caused environmental decline to approach such existential levels, and this is simply a reality which the state can no longer ignore from a security perspective: the West is threatening itself, both directly and indirectly. Since the ostensibly quasi-successful pursuit of traditionally conceived national security in the 20th and early 21st centuries still evidently allowed the West to end up in this environmental security dilemma of its own making, the notion of ‘national security’ seems to need some environmentally-cognizant amendation. The concept of ‘organic national security’ (Snow, Citation2023) offers one such possible renovation of the term.

Organic national security

The modern Western nation-state has its origins in protecting and advancing trade and economic interests, and organising military loyalties, in post-feudal system ways (Spruyt, Citation1996). The economic and security arenas arguably remain its twin engines, its two key fulcrums or sources of determinative power.Footnote2 Policies, laws, and decisions shaped and applied by both of these main core areas of the state have embraced and normalised SEDCOV since at least the dawn of the state as a colonial and then an industrial entity, and particularly since the discovery of oil. Contemporary Western economies and militaries both still run on cheap oil and on a cavalier approach to the natural world (with the sole exception of the taboo (so far) on nuclear weapons use in the post-WW2 period due to the foreseeable environmental impacts being judged as too severe). The West has since its colonial age, increasingly since its age of oil, and then especially in the post-WW2 era, overseen and led the removal and contamination of the living world at a truly staggering scale. The West has personified severe anthropogenic environmental degradation, contamination, and vanishing; it has embraced it at scales small and large as it sought wealth, prosperity, and security. However, if the scientific evidence is correct, SEDCOV has now shown itself to be a way of intervening in nature which erodes the stuff of life to an existential degree, and so many decades of it have left the West now without much of a remaining window to wind down SEDCOV deliberately and by choice (Bradshaw et al., Citation2021; Ehrlich & Ehrlich, Citation2013; IPBES, Citation2019; IPCC, Citation2023).

The West is arguably at a crossroads where, if the “twin engines” claim above is true, there are five main possible paths forward. First and second, the Western nation-state could develop either an economic prosperity-based or a security-based rationale for implementing a true divorce between SEDCOV and the West. Third, the Western state could relatively quickly look to develop a new locus of power within its core structure which was specifically environmental in its focus, to rival the traditional twin engines of the state, one which would somehow also be able to direct real state behaviours at scale and overall, beginning with halting SEDCOV as quickly and safely as possible, even over the objections of the traditional economies and security apparatuses which might oppose it. Fourth, the nation-state itself could be outcompeted and replaced by a new form of sovereign political organisation full stop, one which would be better suited to shepherd its people through this environmentally circumscribed century in a pro-survival manner. Head et al. (Citation2017) imagine one variety of this where additional layers of governance organs specifically tasked with regional environmental issues are added on top of existing states; in another example, some indigenous and tribal communities already try to retain traditional power structures as their own alternatives to nation-states, including as part of their approach to protecting their own local environments.

The fifth road open to the West is the one where nothing substantively changes: the state continues to presume traditional economies and security approaches can continue to carry out SEDCOV as a means to their ends (while also coping with global environmental decline and its security and economic impacts); the two traditional twin engines remain dominant over state behaviour and continue to box environmental decision-makers out of the exercise of determinative power in the West; and no serious competitor forms of political organisation arise to take the nation-state’s place. Where the fifth road leads is uncertain. If the majority of conservation and climate scientists are correct, this road may lead to the collapse of complex human societies and possibly an end to the human species (Bradshaw et al., Citation2021; Ehrlich & Ehrlich, Citation2013; IPBES, Citation2019; IPCC, Citation2023; W. Rees, Citation2017). If collapse scenarios were to one day begin rapidly, too quickly for Western societies to backtrack and take one of the other four roads, the West (and the rest of the globe) could enter a period of anarchy or something even worse, en route to these outcomes. The fifth road is the one the West appears to currently be moving towards taking. There are no major signs, beyond some anaemic ‘pro-nature’ legislation which is raised from time to time, that Western states perceive this road to be particularly problematic or to present any real need for change beyond muddling through with supporting renewable energy sources and with some small efforts at investing in so-called mitigation, adaptation, and resilience measures, especially for the global South.

If we accept for the sake of argument that the fifth road is not a secure road to choose based on scientific evidence (and to some extent our simple direct observation of the vanishing and degradation of the natural world around us), the second of the five possible roads emerges as arguably the most feasible and the least bad of the five, at least in the short term. With the organic national security concept as a conceptual frame, the state could begin a process of highlighting SEDCOV as irrational (Snow, Citation2023), taking its first tentative steps down this second path— the path which, again, requires a security rationale for effecting an actual divorce between SEDCOV and the West.

National security itself has always been an elastic term (Baldwin, Citation1997; Nevitt, Citation2020; Wolfers, Citation1952) sensitive to historical contexts and requirements. As Cuéllar (Citation2009, e.g. pp. 706f.) notes, the United States was experimenting with developing federal domestic security mandates in the 1930s (the era of the Dust Bowl environmental crisis) which went some way towards acknowledging biosphere preservation concerns as a core part of national security. The phrase ‘organic national security’ also has relevant precedent in that this phrase is sometimes used to refer simply to the domestic side of national security (cf. e.g. Dmytryszyn, Citation2012, p. 20) with perhaps sometimes a further connotation of looking especially at the need to secure the organs of the state itself from threat (things like secure internet or radio networks, senior personnel, physical seats of government, police and national guard bases, etc.). Without departing too far from these familiar connotations, we can extend the notion to include the environment — not just countable resources or food supplies but the in situ natural world as a whole with all its humanity-supporting functions, species, and intangibles usually taken for granted (air, water, an enabling ecosystem for the production of food, etc.) — as forming the ultimate foundational layer of the state’s organs and the state itself. If this natural in situ world can no longer simply be taken for granted, but is instead constantly being eroded, degraded, contaminated, etc., this places all the state organs and functions resting atop it and relying on it in potential jeopardy.

Organic national security conceptions can also link with recent efforts to challenge the notion of the post-WW2 West as military ‘sanctuary’ (Deveraux, Citation2023), i.e. territory presumed to not be subject to direct major military threats. Deveraux (and others) have noted that 21st century transnational threats like asymmetrical terrorism, cyber-attacks, and pandemic viruses mean the Western state is in fact ‘sanctuary no longer’ (Deveraux, Citation2023). Global environmental decline, particularly when we note its origin within the West itself, is another sanctuary-breaking reality. The West's security community (though not its scientific community) seems overall to still have an environmental 'sanctuary' mindset: this might entail assumptions that the West’s territories can be taken for granted as an hospitable and permissive habitat for tens or hundreds of millions of humans no matter how those humans interact with their environment; that the South will continue to supply natural goods and resources to cover any gaps the West has; that the West will not itself be targeted by rivals for more natural goods or resources than it can safely part with; etc. In contrast to such outdated assumptions, the inherently precautionary framing of the organic national security concept can highlight that the end of such an 'environmental sanctuary' mindset is just as overdue as the West setting aside its military sanctuary mindset.Footnote3

There are also internal social and political elements to consider as we seek to define organic national security. Environmental decline forms an all-encompassing quicksand for the state from this security standpoint as well. If and as the environment continues to decline, it will be harder for governments to, as it were, justify their own existence. As people’s environments become less viable - a subjective judgment which will vary by region and by group - political disenchantment and either gradual or sudden withdrawal from any version of social contract with holders of power could logically result. The more the state loses its mandate as a result of apparent failure to protect the source of its people’s life and health, the more the state could lose its ability to perform its core functions in the social-political sense too, leading to state fragility.

As direct or indirect environmental stressors on the public move people to act (or refuse to act) in political ways, it is not difficult to extrapolate to a scenario of complete organic national security collapse that would be a special brand of state failure. We can already see incipient hints of these dynamics in places like Lebanon (Oskanian, Citation2021), Iran (Dorsey, Citation2018), and during the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ upheavals in North Africa and the Middle East. In cases like these, citizens of the country directly perceive physical things about their environment which distress them, many of them stemming from their own (and global) governments’ acts of SEDCOV – pollution, contamination, overcrowding, a lack of reliable agricultural systems, a lack of potable water, etc.,-- and then politicise them via things like boycotts, protests, strikes, or demands for governmental change, not just to the detriment of one party or individual or other, but also potentially to the detriment of the regime system or state itself.

In sum, I would like to propose the following definition for organic national security:

Organic national security is achieved when a state can indefinitely:

A) maintain and viably carry out its core functions,

B) provide for its population's physical survival, and

C) protect the environmental foundations of A) and B).

More traditional notions of national security, while they may also point to A) and B), tend not to include C), seemingly either assuming it as a given, or being unwilling to question (or even structurally incapable of questioning) whether the vast security and economic boon which Western states have achieved on the back of SEDCOV practices eventually leaves a significant and even unprecedented security cost in its wake. Relatedly, traditional approaches to national security also seem not to stress the `indefinite' modifier which forms a key term in our above definition. Rhetorically, and politically, the West projects confidence about the future continuation of contemporary economic and security practices. But the West's embrace of SEDCOV as the backbone of these practices de facto nullifies the `indefinite' requirement, as well as any claim to attend to C).

Further defining SEDCOV

One immediate benefit of identifying organic national security as distinct from traditional national security is that it enables Western states to look afresh at the types of behaviours they are carrying out at home (and eliciting or demanding from others in the international system) which are causing such extreme environmental damage and driving the associated security risks: SEDCOV. We need the organic national security concept in order to reconsider SEDCOV, because in contemporary traditional frames, SEDCOV remains braided into security postures and into unquestioned assumptions about how to keep the state safe. Starting to look in a different way at the extent and depth of SEDCOV integrated into mundane state behaviour is key to beginning to grapple with the internality and severity of the threats to the West tied to global environmental decline. Doubtless an entire new lexicon of terms waits to be developed surrounding organic national security.

As part of this new lexicon, SEDCOV as a single unified term can provide national security communities with a rough indexing tool, a simplified qualitative element to look for in state behaviors as one way to glimpse the threat they may pose to organic national security. Once applied, they would find the SEDCOV label or quality fits a plethora of mundane Western state decisions and positions. Many of these are conceived as securing economic or military security advantages. Yet now, we can argue that despite this aim, policies which entail severe environmental damage directly detract from organic national security. Developing tools for the national security apparatus itself to get in the habit of considering which state actions or positions entail SEDCOV is not intended to stand in the way of, or replace, the process by which the national security community routinely collects in-depth scientific analysis on any number of environmental questions from experts. SEDCOV is meant to serve as a term or a concept which can mesh with real security discourse. Policymakers make their decisions on traditional national security in a pragmatic and ideas-based way; they must be able to make their organic national security assessments in this same mode. The SEDCOV term thus is meant to be broad, intuitive, and power-related; qualitative and able to be joined with questions of judgement; contestable on normative and subjective as well as objective grounds; etc. – in short, one which meshes with the way real states make decisions on maximising security.

To offer a nuclear weapons comparison, nuclear weapons scientists and engineers who understand the technical workings of nuclear weapons, or climatologists who are experts in how the climate and earth systems would react as physical systems should these weapons go off in large numbers, are not the ones who practice the art of statecraft or exercise power so as to avoid these outcomes, nor would they necessarily have the ability to do so if they tried. The way that national security professionals, military leaders, heads of government, and so forth, routinely make reference to the special kinds of states of [geopolitical] affairs that nuclear weapons’ presence in the world’s arsenals create is not 'scientific,' even if these states of affairs' underlying physical aspects are known to them only via the expert science. Security policymakers and scholars build on their understanding gleaned from the science in order to understand and frame the power realities these weapons create in ways lying outside the biogeochemical dimension. The nuclear strategy lexicon which leaders or security experts use in this way is large; it includes terms such as deterrence, the nuclear guarantee, mutually assured destruction, proliferation, fear of ‘nuclear weapons falling into the wrong hands’, and so on. These phrases are not in themselves scientific, or, in their political and power context, even always precise. They can change their colour and even sometimes their meaning depending on the person using them, the context, and so on.

So, too, do national security professionals who are truly going to grapple with the unprecedented type and scope of threat posed by Western-driven environmental decline need a lexicon with terms which accept, and do not deny, the frame of national interests, subjectively perceived risks, opportunities for political and security gains, etc., in which they will be used. At the same time they need to have some relevant scientific concepts worked into their amalgams, just like in the nuclear case. Indeed, it is perhaps partly because they are in need of established lexicons useful to security practitioners that these communities in Western states have thus far tended to shoehorn the global devastation of the living non-human world into timeworn concepts of traditional national security and traditional foreseeable (and largely external) threats thereto. If we want to offer potential ways of improving on this approach, we cannot throw off the requirements placed upon the conceptual tools in question by the contexts of power.

We can further define SEDCOV, and sketch how it might form, after organic national security, a second term in a new environmental security lexicon, as follows.

[S] Severe anthropogenic: Severe is a ‘how/in what way’ aspect of the behavior under consideration; anthropogenic is a descriptor of the ‘who’ of the behavior, designating it as coming from a human agent or actor – in this case, specifically some actor at the nation-state level or scale. There are three main sub-elements of severity:

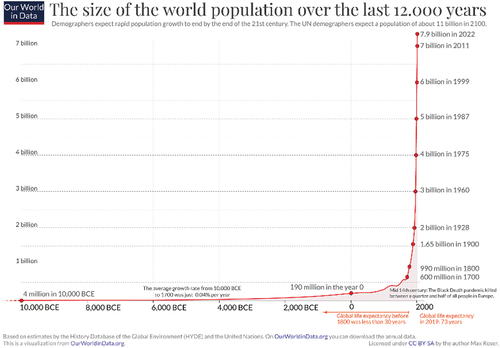

Human numbers: The more iterations or repetitions the permitted environmental behaviour goes through, the more severe it tends to potentially be. Numbers are arguably the most important element of severity in assessing whether a national policy should earn the SEDCOV label. For example, allowing one hundred cars to be owned and driven is perhaps not a severe impact on the non-human world as a whole, while encouraging 1.4 billion cars (the current estimated number of cars on the road worldwide as of 2022, cf. Hedges & Company, Citation2023), to be produced and driven is. The human population is usually counted as roughly 8 billion as of 2023 (cf. ). In functional terms, however, it can be thought of as at least 16 billion, because global Northerners, of whom there are approximately 2 billion countable individuals, impact the Earth as though they were at least 10 billion in terms of how much they consume, if we use the UN’s ‘lower-middle income’ person as our standard (United Nations (UN), Citation2019). Thus in some senses, the states of the global North are currently trying to provide for the security of, and otherwise serve the needs of, what the rest of the world would count as 10 billion people. Some scientists estimate that in order for the planet to be able to support the human species indefinitely, the global human population would have to be much lower (cf. e.g. Crist et al., Citation2022; Lianos & Pseiridis, Citation2016). There are ethical, woman-focused, individual human freedom-protecting ways to go about gradually bringing down human numbers everywhere; the states of the West, for their part, can reduce their effective population somewhat more rapidly, by reducing needless overconsumption of resources, including the percentage of food brought to market in the US and Europe which is wasted, which in 2011 hovered around 40 percent (Smil, Citation2011, 629-630). Reducing both real and effective population numbers is one potentially vital way of ameliorating the organic national security dilemma in which the world (including the West) now finds itself.

Figure 1. Estimated world human population, 10,000 BCE – 2021 CE. (License: CC-BY).

Time: The second most important element of severity is duration, though duration needs to be considered in a few different ways. First, at the direct scale, the longer in duration any human impact on the non-human web of life can be predicted to last, the more severe we can consider it. Some novel contaminants humans have released in vast quantities into the biosphere (Brunn et al., Citation2023) will be there for thousands of years. Secondly, states must consider asynchronous impacts (or what seem asynchronous by human standards). We still have not yet seen what we have already done to biodiversity (Cornford et al., Citation2023; Gosselin & Callois, Citation2021; Tilman et al., Citation1994) or to climate (Hansen et al., Citation2023). A third temporal aspect of severity is that the earth experiences all Western states’ (and all human) impacts throughout history to the current day as a cumulative total force acting on its integrity, though states like to consider decisions in isolation, often packaged into narrowly framed environmental impact assessments which ignore the possibility of one last proverbial straw being what breaks the camel’s back. As late as approximately 1960, the world’s ecosystems still possessed a ‘substantial ecological reserve’, but this had ‘disappeared after 10 [more] years’, i.e. by approximately 1970 (Lianos & Pseiridis, Citation2016, 1682). The Mediterranean Basin sustained human civilisations for millennia, but is now at risk of complete ‘agro-ecological’ and ‘ecosystemic’ collapse in the short term (Head et al., Citation2017).

Intensity: A third element of severity is the physical intensity of the impact being considered seen in and of itself. Contemporary forms of coal, oil, and natural gas extraction, metal ore and minerals mining, technologies like the internal combustion engine or the nuclear reactor, and production of substances like plastics, chemicals, advanced materials, electronics, etc., are often more intense in their impacts on the non-human world, when considered in and of themselves as types of intervention, compared to the types of impacts and interventions humans generated throughout most of human history via hand tools, fire, human and animal strength, etc. Industrialized farming, for example, is in itself more mechanically and chemically intense in its effects on soil and waterways than older forms of agriculture, or than some forms of traditional hunting and gathering. Advances in humans’ abilities to bioengineer viruses, bacteria, potentially one day even new forms of multicellular organism, also create potential forms of high intensity impact on the non-human world.

[E] Environmental is ‘where’ the behaviour is impacting: the in situ air and atmosphere; all waterways including the oceans; soil and all other parts of the Earth’s crust; all other wild species, whether animal, bird, plant, insect, fish, etc.; and all the complex wholes the interplay of all four of these create, sometimes referred to as the biosphere, atmosphere, oceans ‘systems’, climate, landscapes, ecosystems, complex systems, nature, the environment, etc. Again, the focus is directed toward the impacts of a policy on the entire physical place constituting the country, not on the condition or quantity of any one or more countable or quantifiable ‘natural resource’ stock.

[D] Degradation is the first of three terms for the ‘what’, the substance of the action the national security community is referencing or identifying the presence of. The organic national security evaluator will ask: does the decision or position cause degradation? Degradation refers to any lowering of the integrity and previous/historical way of functioning of one or more parts of the environment. For example, industrial farming techniques and heavy chemical fertiliser and pesticide use cause soil and land degradation. A previously wild habitat might become degraded by air pollution, light pollution, the presence of domesticated species, or the construction of roads nearby, even if it appears to still be undeveloped or protected (cf. e.g. Albert et al., Citation2023; Newbold et al., Citation2015; Smil, Citation2011). Bentley offers a fairly standard definition of environmental degradation from a scientific standpoint (Bentley, Citation2022); this scientific sense of the term, where some physical ability of a place to support human and other species’ survival needs is reduced, can be complemented by an experiential sense of the term as well, where degradation corresponds to some loss of richness or texture in some place or locality, as felt or perceived by some community of humans (and presumably, if recent research into animal intelligence is correct, possibly also in some sense(s) by some non-human species as well).

[CO] Contamination is the second of three terms for the ‘what’, the substance, which a person gauging the organic national security impact of an action or policy will be looking to confirm as either present or absent. Contamination refers to the release of pollutants, waste products, and other problematic substances into the air, land, and waterways, affecting the health and survival of numerous species and harming human health as well: e.g., air pollution, contaminants resulting from industrial and chemical waste, oil spills, mountains of non-biodegradable trash or electronic waste, etc.

In Canada, the US, and Mexico, combined, industries reported ‘more than 5.1 billion kilograms [of pollutants emitted] in 2014’ and ‘almost 5.3 billion kg in 2018’ (roughly 5.1 million tons and 5.3 million tons, respectively) (Commission for Environmental Cooperation, Citation2023). Canadian industries reported in one year (2021) the release of roughly 2.8 million tons of pollutants into the air and 150,000 tons of pollutants into water and into the land (Government of Canada, Citation2022); pollutants included ‘162 different substances’, and the ‘pollutants released in the highest quantities were carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide (expressed as nitrogen dioxide), and particulate matter’ (Government of Canada, Citation2022).

Plastic waste including microplastic particles is now found in the natural environment worldwide, in the bodies of fish and birds, and (as microplastic particles) in the human bloodstream and lungs (Leslie et al., Citation2022; Jenner et al., Citation2022). PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ have contaminated the entire planet (Paz, Citation2022) and in Europe ‘people are constantly exposed to a mixture of chemicals’ (European Environment Agency, Citation2020). Contamination is often linked with adverse health impacts in wildlife and humans; the WHO claims that ‘nearly a quarter of all [human] deaths globally can be attributed to environmental impacts on health’ including (among others) cases of contamination such as ‘air pollution’, ‘chemical exposures, radiation’, and problems in ‘the built environment’ (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2024).

[V] Vanishing is the third of three ‘what’ terms organic national security assessors would be interested in determining as either present or absent in a national position or policy. Vanishing refers to humans 'vanishing' some piece of the non-human world in a permanent fashion. For example, a dense forest clear-cut for grazing; a grassland paved for a shopping mall and parking lot; a large volume of some wild species like elephant or tuna killed too rapidly for them to replace themselves; etc. It also refers to the extinguishing of an entire species altogether (Platt, Citation2021).

Humans' vanishing of non-human habitats and landscapes permissive for other species has gotten so prevalent that wild animals, insects and wild plants are running out of places to live (Einhorn & Leatherby, Citation2022; Tilman et al., Citation1994). Species staying short of extinction are still being vanished from the Earth in terms of real population numbers (WWF, Citation2020; Ceballos et al., Citation2015). The biggest drivers of direct environmental vanishing are the push for new (non-regenerative) agricultural land (Bendell, Citation2023; Dudley & Alexander, Citation2017) and the direct harvesting or “take” of trees, individual living animals and fish, and other plants for human consumption (Maxwell et al., Citation2016). Meanwhile the vanishing of wild or semiwild land (in pieces both large and small) for the sake of residential, commercial, or infrastructure development is perhaps the most readily visible kind of vanishing for the majority of citizens in the West. Vanishing is also a built-in flipside to the production of consumer goods of all kinds. There is no such thing as a standalone product; objects and substances which humans in the West consume as inert things entail vanishing, sometimes far afield, and often in the global South (Hickel et al., Citation2022). Even ‘simple’ materials like ‘concrete ... bricks, asphalt, metals, ... glass and plastic’, the cumulative mass of which Elhacham et al. (Citation2020) find now equal and are set to outweigh living biomass globally, always incur vanishing. To make concrete, silicon, glass, and other materials requiring sand as a ‘raw material’, for example, the world consumes roughly 50 billion metric tons per year of sand (Newcomb, Citation2022). To get the sand, people ‘strip riverbeds and beaches bare’, and there have also been reports of people ‘ripping up forests and farmlands just to get to more sand’; just as sand in situ plays a vital role in ecosystems, and takes thousands of years for nature to form (Newcomb, Citation2022), sand made into a human consumer good or material represents a vanishing (and anthropogenic conversion) of this part of the ecosystem (with many follow-on effects) wherever it was extracted.

Vanishing meshes particularly easily with the notion of a violation of organic national security, because we can fairly easily understand the vanishing of whole landscapes (World Wildlife Foundation [WWF], Citation2022), entire species (Platt, Citation2021), an entire inland sea (Waehler & Sveberg Dietrichs, Citation2017), and so forth, as something akin to a military loss of territory; whichever state is allowing the vanishing to take place is quite literally relinquishing permanently a part of its means of physical survival.

Vanishing pieces of the living world is arguably a particularly final and inherently existential act with extraordinary and still little-appreciated risks and costs for states and their people, both physical and social.

Gauging SEDCOV from within a security context

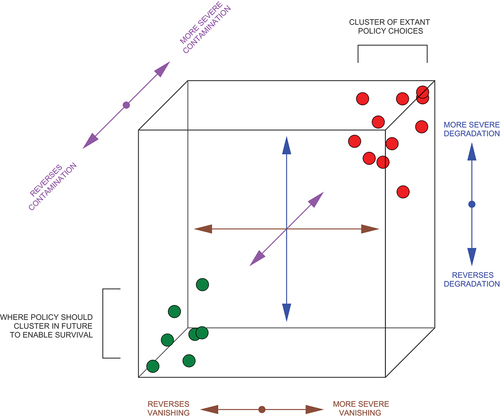

Evaluating in rough, qualitative terms, from within a[n organic] national security framework, whether a given decision or policy entails SEDCOV can be visualised as locating the foreseeable outcomes of the policy or decision within a cubic space where one axis is degradation, one contamination, and one vanishing. Along each axis, the all-important qualifier of severity moves the coordinate value up from a zero point of neutral non-impact. (Regenerative behaviors like cleanup, rewilding, or replacement could also create negative values along the appropriate axes.) The point here is only to imagine a rough rule of thumb, an intuitive ‘on a scale of 1 to 10’ type habit of mind that non-scientists could use in a security and power context, not develop a precise quantification tool. See .

Figure 2. A visual representation of the SEDCOV rough litmus test for state actions, for use by non-scientist national security practitioners and adjacent expert communities. (Diagram designed by author, and executed and enhanced by Adie Mitchell, Princeton School of Architecture).

Applying this rough tool to understand mundane state behavior in a new security light could form the first steps down the second of the five roads out of the West's current environmental security dilemma – the road of developing a security rationale for weaning the Western state off of SEDCOV across all policy domains, and leading (to the extent possible) the entire global community of states toward the same choice. Grappling with why environmental decline is so very bad for itself as well as other states that it is not in its domestic or external security interest to continue to allow it to happen will take time; beginning to canvas in intuitive and conceptual ways what kinds of things the state needs to do and not do if it is to avoid continuing to lead the world into ever-greater amounts of environmental decline is only a first step. Getting into a habit of mind where moving policy, across all formal policy domains, from the right/upper/back to the left/lower/front part of the cube becomes an ingrained goal will take even longer.

We would argue, however, that mapping these realities can no longer be neglected in the study or practice of coherent national security strategy. Even just focusing on a single issue like fossil fuels and CO2 levels, in isolation from the bigger issue of degradation, contamination, and vanishing of the natural world itself, is a trap which even those, like Dalby, who otherwise seem intent on renovating the definition of environmental security, still tend to fall into (see, e.g., Dalby, Citation2022, p. 32, where he writes that ‘the causes of environmental insecurity now lie in the massive use of fossil fuels’). Fossil fuel combustion at scale is arguably better understood as a symptom, rather than the root cause, of the paradoxical organic insecurity attaching to the Western state today: the root cause of this insecurity is that the West still has not accepted that SEDCOV is inherently existentially risky, or been willing to re-evaluate in self-critical ways how it is threatening itself (as well as others) with the very oil- and technology-reliance it perceives as still being a viable backbone strategy for this century, ignoring all environmental consequences (or, put another way, ignoring the impossibility of securing the necessary environmental foundations of such a backbone strategy). If barriers are not gradually erected by the state itself against continuing in its SEDCOV-as-normal mindset – if recognition remains wanting of the true character of this class of state behaviours – then the state will soon find its fortunes, as it were, not just threatened from without, but swallowed up entirely from within as it sinks a little more each year in the quicksand of environmental decline and its cascading effects.

The implicit destination, the inherent logic of the West’s longstanding SEDCOV-entwined approach to pursuing security and prosperity is in a sense degradation, contamination, and vanishing all going up to a 1 value in every domain: then the state’s work will be ‘complete’, the absolute maximum will have been gotten out of the earth, and so forth. This means that SEDCOV does not pair with an actual security mindset. Reaching the ‘1’ value is not physically survivable; as noted above, humans require a relatively biodiverse and relatively intact and functional biosphere, relatively successfully inhabited by millions of species in addition to our ownFootnote4, in order to persist ourselves (Bradshaw et al., Citation2021; IPCC, Citation2023; W. E. Rees, Citation1992; Sala & Rechberger, Citation2019; Steffen et al., Citation2018).

Concluding discussion

States in the West, in tending to their national security, generally look at a) various causal pathways through which bad or risky security outcomes could land at their feet, b) what these risks look like in detail when they do arise, and c) how the state can respond to and counter these bad outcomes and threats. Currently, when it comes to environmental decline, the Western national security community has seemingly accepted that climate change and environmental degradation are a new kind of a), but fallen largely into traditional or neo-traditional, rather than environmentally-minded, thinking when turning to what b) and c) look like in this case. While acknowledging that bad outcomes are likely to arrive as a result of climate change (and to some extent broader environmental degradation), the West has not yet fully grappled with the existential [organic] national security risk-taking inherent in Western states’ mundane policy decisions resting on SEDCOV modes of thinking. The larger picture of the acts through which Western states continue to cause degradation within the West and globally, and the indiscriminate quicksand this degradation has already put under all states including Western ones, is set aside – a luxury afforded the West not by reality, but only by its outdated environmental sanctuary mindset and its lack of a lexicon for discussing normalised domestic SEDCOV behaviours as undermining of domestic and global security.

To more fully rise to the challenge of the unprecedented scope and scale of the environmental decline threat, the West’s security community can question this current approach, and begin to expand its view of its own environmental security dilemma and paradox. This can begin with simple steps such as embracing an organic national security discourse and awareness, and beginning to properly characterise SEDCOV as always posing a direct threat to this type of security.

Because of the West’s embrace of SEDCOV at national and global scales, because in almost every instance, across all policy realms, it continues to default to setting no limits on human degradation, contamination, and ‘vanishing’ of the non-human world, while failing to acknowledge that this insistence on limitlessness is making us less secure, rather than more secure, the entire world has currently lost the ‘indefinite’ modifier in the definition noted above of organic national security. What may matter most of all in the entire environmental security landscape of the current moment in the West is simply getting Western states’ core loci of power to actually see and acknowledge that currently they can reasonably claim only to be temporarily securing and preserving their core functions and the physical survival of their populace, because they are not attending to the environmental foundations of the state and its people. Once this acknowledgement is publicly, openly, and seriously made by the West’s core state functions (not peripherally, or solely rhetorically, while leaving the preponderance of state actions untouched), the imperative to replace the limited timer once more with the indefinite qualifier may then finally crystallise into a new and revivifying purpose for the Western state which finally matches the urgency long advocated for by conservation scientists (Bradshaw et al., Citation2021; Catt & Mason, Citation2023; Díaz et al., Citation2019; IPCC, Citation2023; Ripple et al., Citation2017; United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), Citation2023).

Out of the five possible roads forward available to the Western state in its contemporary environmental security dilemma, developing a national security rationale that could in principle fairly quickly move the state to where it (according to environmental scientists) needs to be is, it appears, the most realistic, least bad option. This paper has presented two elements which can hopefully form a contribution to the national security community’s modes of thinking about their crossroads and about how to take the first few steps down this second path.

Our earth is a giant, completely interconnected, richly chemically- and life-endowed sphere which only took on the shape it did by being able to respond to stimuli; by being sensitive, reactive, and constantly evolving through time. These are the very conditions which created life, including our own species, over billions of years. There is no such thing as a planet which is both capable of spawning millions of species, including the human one, out of some type of raw ‘primordial soup’ of plain molecules acting and reacting among themselves over billions of years (cf. e.g., Kahana et al., Citation2019), and at the same time capable of holding itself unshakeably stable and un-‘crash’-able while we do our worst to it. It is built into the bargain of being one of the species literally made by the earth that our earthly home reacts to us; we simply would not be here were we not part of this dynamic where our every action is both shaped by and impacts in turn the rest of the natural world (cf. also Dalby, Citation2022, p. 18). If the West does not acknowledge this as the foundational, basic security situation of the nation-state, it is practicing not realism but a particularly problematic form of hollow idealism.

We can glean from the scientific side of the environmental security discourse that the West does not have plenty of time and space ahead in which it can experience a long string of environmental decline-caused, but traditionally experienced and parsed, threats coming from other regions and peoples. If the climate security or environmental security discourse on the national security side continues along its current track of charting how massive climatic and ecological negative changes may impact various states and regions far afield and how these impacts might in turn impact the West’s security, it is hard to escape the thought that this side of the discourse is ignoring the most important kernel of the scientific half of the discussion. In the West’s highly imperfect, but in the end hopefully still somewhat survival-oriented, nation-states, it is time to turn national security attention inward, and rethink some very basic assumptions long held by those expert in the study and exercise of power, beginning with the assumption that they are the only actors, and the natural world is merely their solid stage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This is of course, again, not to say these discussions are not being held, for example by local communities where Western extractivism impacts most visibly, or globally by a range of environmental activists and scholars within and beyond the natural sciences; only to say these discussions are not usually being held within this practical and pragmatic, military- and security-sector-engaged side of the environmental security discourse.

2. I.e., having the most power or influence over what the state, its corporate actors, and its individuals do overall, and at scale, notwithstanding exceptions to the rule which might be carved out in hard-fought battles by (relatively powerless) regulatory agencies or other more ‘pro-environment’ parts or members of the state.

3. Indeed, these two required shifts in perspective (one, the shift away from military (and regime) sanctuary assumptions, and two, the shift away from environmental sanctuary assumptions) can be seen as intertwined, though there is not space to elaborate on this point here.

4. Estimates of the Earth’s total number of species vary from a few million to one trillion; c.f. e.g., Hannah Ritchie (2022) - “How many species are there?” Published online at OurWorldInData.org, cf. https://ourworldindata.org/how-many-species-are-there.

References

- Albert, J. S., Carnaval, A. C., Flantua, S. G. A., Lohmann, L. G., Ribas, C. C., Riff, D., Carrillo, J. D., Fan, Y., Figueiredo, J. J. P., Guayasamin, J. M., Hoorn, C., de Melo, G. H., Nascimento, N., Quesada, C. A., Ulloa Ulloa, C., Val, P., Arieira, J., Encalada, A. C., & Nobre, C. A. (2023). Human impacts outpace natural processes in the Amazon. Science, 379(6630), eabo5003. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo5003

- Al-Marashi, I., & Causevic, A. (2020). NATO and collective environmental security in the MENA: From the cold war to covid-19. Journal of Strategic Security, 13(4), 28–16. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.13.4.1804

- Baldwin, D. A. (1997, January). The concept of security. Review of International Studies, 23(1), 5–26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097464

- Bendell, J. (2023). Beyond fed up: Six hard trends that lead to food system breakdown. Institute for Leadership and Sustainability (IFLAS) Occasional Papers, 10. ( Unpublished/Preprint) : http://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/6927/

- Bentley, R. (2022). Causes and factors of environmental degradation. Journal Geographical Natural Disaster, 12(1), 1000238. https://doi.org/10.35248/2167-0587.22.12.238

- Bradshaw, C. J. A., Ehrlich, P. R., Beattie, A., Ceballos, G., Crist, E., Diamond, J., Dirzo, R., Ehrlich, A. H., Harte, J., Harte, M. E., Pyke, G., Raven, P. H., Ripple, W. J., Saltré, F., Turnbull, C., Wackernagel, M., & Blumstein, D. T., et al. (2021). Underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 1, 615419. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2020.615419

- Brunn, H., Arnold, G., Körner, W., Rippen, G., Steinhäuser, K. G., & Valentin, I. (2023). PFAS: Forever chemicals—persistent, bioaccumulative and mobile. Reviewing the status and the need for their phase out and remediation of contaminated sites. Environmental Sciences Europe, 35(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-023-00721-8

- Busby, J. (2022). States and nature: The effects of climate change on security. Cambridge University Press.

- Catt, H., & Mason, T. (2023). Too late to save environment, says green party co-founder. BBC.com. Retrieved 2 March 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-64815875

- Commission for Environmental Cooperation. (2023). Taking Stock: North American pollutant releases and transfers (Vol. 16, p. 138). http://www.cec.org/tsreports/

- Cornford, R., Spooner, F., McRae, L., Purvis, A., & Freeman, R. (2023). Ongoing over-exploitation and delayed responses to environmental change highlight the urgency for action to promote vertebrate recoveries by 2030. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 290(1997), 20230464. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.0464

- Crist, E., Ripple, W. J., Ehrlich, P. R., Rees, W. E., & Wolf, C. (2022). Scientists’ warning on population. Science of the Total Environment, 845, 157166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157166

- Cuéllar, M.-F. (2009). “Securing” the nation: Law, politics, and organization at the federal security agency, 1939–1953. The University of Chicago Law Review, 76(2 Spring) 587–718.

- Dalby, S. (2009). Security and environmental change. Polity Press.

- Dalby, S. (2013). The geopolitics of climate change. Political Geography, 37, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.09.004

- Dalby, S. (2022). Rethinking environmental security. Edward Elgar.

- Deveraux, B. (2023). Sanctuary No longer? Examining the defense department’s prioritization of the homeland. War on the Rocks. Retrieved June 6, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/06/a-sanctuary-no-longer-examining-the-defense-departments-prioritization-of-the-homeland/

- Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E. S., Ngo, H. T., Agard, J., Arneth, A., Balvanera, P., Brauman, K. A., Butchart, S. H. M., Chan, K. M. A., Garibaldi, L. A., Ichii, K., Liu, J., Subramanian, S. M., Midgley, G. F., Miloslavich, P., Molnár, Z., Obura, D. … Willis, K. J. (2019). Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science, 366(6471), eaax3100. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax3100

- Director of National Intelligence. (2023). Annual threat assessment of the U.S. Intelligence community. Office of the Director of National Intelligence. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf

- Dmytryszyn, M. C. (2012). “A U.S. Minimum nuclear deterrence strategy”: By design or default it’s about the policy options [ Master’s Thesis]. School of Advanced Air and Space studies, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/AD1019369.pdf

- Dorsey, J. M. (2018, June). Remembering Syria: Iran struggles with potentially explosive environmental crisis. The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, 37(No. 4), 32–33. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/remembering-syria-iran-struggles-with-potentially/docview/2052629574/se-2

- Dudley, N., & Alexander, S. (2017). Agriculture and biodiversity: a review. Biodiversity, 18(2–3), 2–3, 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2017.1351892

- Ehrlich, P., & Ehrlich, A. (2013). Can a collapse of global civilization be avoided? Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 280(1754), 20122845. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2845

- Einhorn, C., & Leatherby, L. (2022). Animals are running out of places to live. New York Times. Retrieved Dec. 9, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/12/09/climate/biodiversity-habitat-loss-climate.html

- Elhacham, E., Ben-Uri, L., Grozovski, J., Bar-On, Y. M., & Milo, R. (2020). Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. Nature, 588(7838), 442–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5

- European Environment Agency. (2020). Living healthily in a chemical world. EEA signals 2020 – towards zero pollution in europe. https://www.eea.europa.eu/signals-archived/signals-2020/articles/living-healthily-in-a-chemical-world

- Gerardo, C., Anne, H. E., & Paul, R. E. (2015). The annihilation of nature: Human extinction of birds and mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Gosselin, F., & Callois, J.-M. (2021). On the time lag between human activity and biodiversity in Europe at the national scale. Anthropocene, 35, 100303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2021.100303

- Government of Canada. (2022). NPRI Data. as of September 29, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/national-pollutant-release-inventory/tools-resources-data/fact-sheet.html#toc0

- Hansen, J., Sato, M., Simons, L., Nazarenko, L. S., Sangha, I., von Schuckmann, K., Loeb, N. G., Osman, M. B., Jin, Q., Kharecha, P., Tselioudis, G., Jeong, E., Lacis, A., Ruedy, R., Russell, G., Cao, J., & Li, J. (2023). Global warming in the pipeline. [Under review/preprint]. https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.04474v3

- Head, J. W., Marples, K., & Simpson, J. (2017). Mediterranean agriculture, ecology, and law: Creating a new non-state actor to counteract agro-ecological collapse in the mediterranean basin. Mediterranean Studies, 25(1), 98–146. https://doi.org/10.5325/mediterraneanstu.25.1.0098

- Hedges & Company. (2023). How many cars are there in the world in 2023? Automotive Market Research. https://hedgescompany.com/blog/2021/06/how-many-cars-are-there-in-the-world/

- Herrington, G. (2020). Update to limits to growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 25(3), 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13084

- Hickel, J., Dorninger, C., Wieland, H., & Suwandi, I. (2022, March). Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. Global Environmental Change, 73, 102467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102467

- Hough, P. (2005, November). Who’s Securing Whom? The Need for International Relations to Embrace Human Security. St Antony’s International Review, 1(No. 2), Human Security (72–87). https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/262270

- Hough, P. (2021). Environmental Security: An introduction (Second ed.). Routledge.

- IPBES. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In E. S. Brondízio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, & H. T. Ngo (Eds.) (pp. 1148). IPBES secretariat. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673

- IPCC. (2023). Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. A report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. contribution of working groups i, ii and iii to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [core writing team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC.

- Jenner, L. C., Rotchell, J. M., Bennett, R. T., Cowen, M., Tentzeris, V., & Sadofsky, L. R. (2022). Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Science of the Total Environment, 831, 154907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154907

- Kahana, A., Schmitt-Kopplin, P., & Lancet, D. (2019). Enceladus: First observed primordial soup could arbitrate origin-of-life debate. Astrobiology, 19(10), 1263–1278. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2019.2029

- Leddy, L. (2020). Arctic climate change implications for U. S. National security. American Security Project. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26606

- Leslie, H. A., van Velzen, M. J. M., Brandsma, S. H., Dick Vethaak, A., Garcia-Vallejo, J. J., & Lamoree, M. H. (2022). Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environment International, 163, 107199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107199

- Levy, M. (1995). Is the environment a national security issue? International Security, 20(2), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539228

- Lianos, T. P., & Pseiridis, A. (2016). Sustainable welfare and optimum population size. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(6), 1679–1699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9711-5

- MacDonald, M. (2018). Climate change and security: Towards ecological security? International Theory, 10(2), 153–180. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971918000039

- Maxwell, S., Fuller, R., Brooks, T., & Watson, J. E. M. (2016). Biodiversity: The ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature [Comment], 536, 143–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/536143a

- Michael, B., Peter Samuel, U., & Eucharia, N. N. (2012,). Environmental Damage Caused by the Activities of Multi National Oil Giants in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (JHSS), 5(6), 09–13. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-0560913

- Nevitt, M. (2020). On environmental law, climate change, & national security law. Harvard Environmental Law Review, 44, 321–366. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/2101

- Newbold, T., Hudson, L., Hill, S., Contu, S., Lysenko, I., Senior, R. A., Börger, L., Bennett, D. J., Choimes, A., Collen, B., Day, J., De Palma, A., Díaz, S., Echeverria-Londoño, S., Edgar, M. J., Feldman, A., Garon, M., Harrison, M. L. K. … Scharlemann, J. P. W. (2015). Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature, 520(7545), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14324

- Newcomb, T. (2022). Earth is running out of sand … which is, you know, pretty concerning. Popular Mechanics. Retrieved May 3, 2022. https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/environment/a39880899/earth-is-running-out-of-sand/

- Oskanian, K. (2021). Securitisation gaps: Towards ideational understandings of state weakness. European Journal of International Security, 6(No. 4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2021.13

- Paz, I. G. (2022). PFAS: The ‘Forever Chemicals’ you couldn’t escape if you tried. The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/12/us/pfas-chemicals-fast-food.html

- Platt, J. (2021). What we’ve lost: The species declared extinct in 2020. Scientific American. Retrieved January 13, 2021, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-weve-lost-the-species-declared-extinct-in-2020/

- Rees, W. (2017). What, Me Worry? Humans Are Blind to Imminent Environmental Collapse. [Opinion.] TheTyee.ca. Retrieved Nov. 16, 2017, https://thetyee.ca/Opinion/2017/11/16/humans-blind-imminent-environmental-collapse/

- Rees, W. E. (1992). Ecological footprints and appropriated carrying capacity: What urban economics leaves out. Environment and Urbanization, 4(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624789200400212

- Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., Galetti, M., Alamgir, M., Crist, E., Mahmoud, M. I., William, F., & Laurance, and 15,364 scientist signatories from 184 countries. (2017). World scientists’ warning to humanity: A second notice. BioScience, 67(Issue 12), 1026–1028. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix125

- Sala, E., & Rechberger, K. (2019). We need to save our wild places. We can’t survive without them. World economic forum. Retrieved Jan 20, 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/why-should-you-care-about-wild-places/

- Schaik, V., Louise, D. Z., von Lossow, T., Dekker, B., van der Maas, Z., & Halima, A. (2020). Drivers of climate security: Ready for take-off? Military responses to climate change. The Clingendael Institute. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep24675.5

- Schoonover, R., Cavallo, C., & Caltabiano, I. (2021). The security threat that binds us: The unraveling of ecological and natural security and what the united states can do about it. In F. Femia & A. Rezzonico (Eds.). The Converging Risks Lab, an institute of The Council on Strategic Risks.

- Schoonover, R., & Smith, D. (2023). Five Urgent Questions on Ecological Security. SIPRI insights on peace and security, No. 2023/05. https://doi.org/10.55163/XATC1489

- Smil, V. (2011). Harvesting the biosphere: The human Impact. Population & Development Review, 37(4), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00450.x

- Snow, K. C. (2023, April 26). Environmental Intelligence and the Need to Collect it. VerfBlog. https://verfassungsblog.de/environmental-intelligence-and-the-need-to-collect-it/

- Spruyt, H. (1996). The Sovereign State and its Competitors. Princeton University Press.

- Steffen, W., Rockström, J., Richardson, K., Lenton, T. M., Folke, C., Liverman, D., Summerhayes, C. P., Barnosky, A. D., Cornell, S. E., Crucifix, M., Donges, J. F., Fetzer, I., Lade, S. J., Scheffer, M., Winkelmann, R., & Joachim Schellnhuber, H. (2018). Trajectories of the earth system in the anthropocene. PNAS, 115(33), 8252–8259. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810141115

- Swing, K. (2022). Risks for the Environment, Biodiversity, Humankind, and the Planet. In J. N. Furze, S. Eslamian, S. M. Raafat, & K. Swing (Eds.), Earth Systems Protection and Sustainability (pp. 189–211). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85829-2_8