ABSTRACT

Adaptive Pathways (APs) enable holistic preparedness for infrastructure assets management across their life cycle, especially in face of disasters. Affected rural communities lose their habitat, food and livelihoods, and access to connectivity. Nevertheless, they can still take ownership and contribute in developing APs for building resilient infrastructure and enhancing combined resilience (physical, economic, community). A coding-based weighted model is used to analyse 8 Case Studies. Key findings are: (a) Strengthening of communities and local institutions through capacity building (communications APs) from inception is prerequisite for combined resilience. This is significant even in absence of other AP factors including evidence-based policy, governance, innovation; (b) Capacity building should focus on designing local resource-based approaches [LRBA], nature-based solutions [NBS], and community indigenous knowledge thereby improving other AP factors; (c) Policy formulation on asset management and quality assurance should be pre-requisite for mobilisation and funds allocation to strengthen community-led APs for combined resilience.

1. Introduction

Rural roads are about 85% of the global road network (ILO, Citation2014). Rural roads are essential for providing infrastructure services, especially physical connectivity. Due to increasing climate conditions such as flooding, there is focus on construction of climate resilient rural infrastructure including all-weather rural roads, embankments, dykes, and drainages for effective water management especially in flood prone areas. As noted in ADB (Citation2022b, p.vii), ‘extreme weather events and geophysical hazards over the same period [between 2012–2021] caused direct physical losses averaging $58 billion per year, or $159 million per day’. According to UNESCAP (Citation2021, p. 2), ‘57% of global fatalities from disasters and 87% of the global population that has been affected by natural hazards’ took place in the Asia and Pacific region. Furthermore, between 1970 and 2020, 2 million deaths and 6.9 billion people were affected (ibid).

When faced with floods, entire villages, and livestock are compelled to take refuge on high road embankments from their low-lying habitats. However, these embankments are susceptible to damage due to overflowing of water across the roads causing extensive damage to the infrastructure assets, mobility, and safety. In disasters, not only are affected rural communities losing their habitat, food, and livelihoods but they are also losing access to key systemic infrastructure services such as roads connectivity, power, education, water, health, and local economic activities.

Hence, given the need to take decisions in uncertainty and forecast prior to/in emergency situations, appropriate Adaptive Pathways (APs) for effective planning, designing, operations, and maintenance are pre-requisites for achieving climate resilient rural infrastructure and services. Other approaches than APs to build and maintain rural infrastructure include costly capital-intensive methods that utilise imported heavy machinery at a large-scale with limited potential for rural employment. These approaches have little focus on flexibility as per on-the-ground needs at the grassroot level in uncertain conditions. Moreover, due to financial constraints, these other approaches are not preferred for rural areas in developing countries for construction and maintenance of public works.

2. Methodology

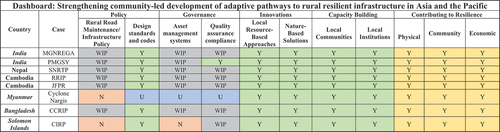

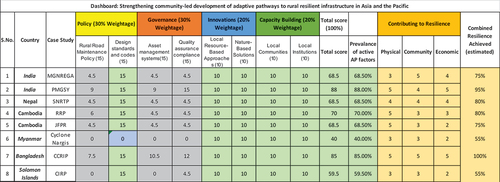

After outlining the rationale for strengthening community-led development of APs, an innovative model and dashboard is introduced that involves coding weighted qualitative data into quantitative scores based on qualitative and quantitative secondary research conducted on case studies. Eight case studies have been studied: India (MGNREGA, PMGSY), Nepal (SNRTP), Cambodia (RRP, JFPR), Myanmar (Cyclone Nargis), Bangladesh (CCRIP), and Solomon Islands (CIRP).

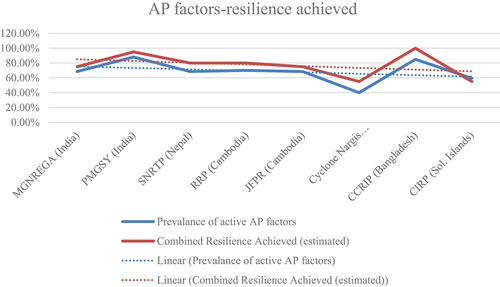

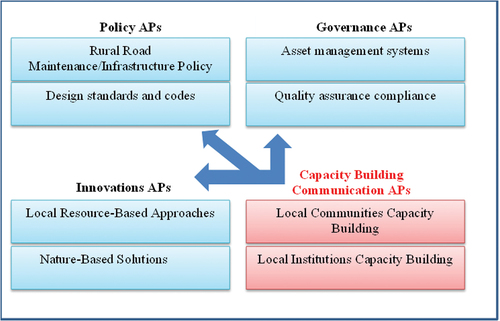

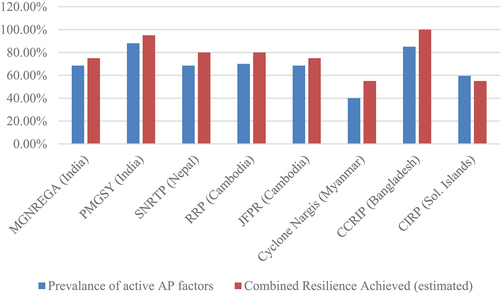

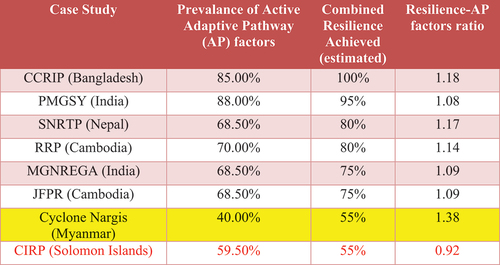

The dashboard shows scores for the following AP factors: (i) evidence-based policy [weightage = 30%]; (ii) governance [weightage = 30%]; (iii) innovation [weightage = 20%]; (iv) capacity building [weightage = 20%]. Within each of the above factors, there are contributing sub factors accounting for equal weightage. All the referred case studies have then been scored out of a value of 1 based on the evidence-based qualitative research through literature review of relevant organisational reports, scientific technical journal articles cited in this paper and observations from hands-on experience of the authors over the past 30 years in international development in leading the interventions. Subsequently, the scores out of 1 are translated into weighted scores, which result in a total score out of 100% for each case study, named as ‘prevalence of AP factors’ in percentages.

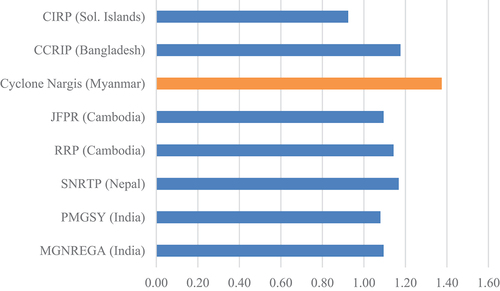

Thereafter, in the same dashboard, scores for Resilience (physical, economic, community) resulting from each intervention are assigned on a scale (0–5) to calculate a combined resilience achieved for each of the respective case studies. Physical resilience has been given a double weightage as compared to economic and community resilience. Physical, economic, and community resilience for a respective intervention have been identified through various sources including observation annotations, impact assessments, and grey literature including technical reports and evidence-based journal articles in the scientific community.

Finally, for policy recommendations, a Resilience-AP factors ratio has been derived to compare the extent of influence from prevalent AP factors on the induced estimated overall combined resilience achieved for each case study. The trends available using this flexible model are displayed using graphs and charts presented in later sections of this paper.

The key underlying assumption of this model is that the analysis done refers to the prevalent conditions in the year(s) of implementation for works stated. As a result, there are many AP factors noted as ‘Work in Progress’ (WIP). When there is lack of information about factors, the respective factor is noted as Uncertain (‘U’). In case a factor is applicable for an intervention, it is designated as ‘Y’ and ‘N’ is written in the case that the factor is not applicable at the time of the respective intervention.

3. Results and discussion on strengthening community-led development of APs

For evidence-based policy making and planning, the top-down approach in decision-making is not comprehensive and optimal. According to Gupta (Citation2019), community-led rural road maintenance through performance-based community contracting has been a successful piloted approach worldwide for the design and performance management of preventive maintenance works for rural roads. LRBA and NBS are cost-effective and allocated funds are better utilised due to prioritisation of needs by the communities, resulting in women empowerment, upskilling, and poverty alleviation.

Indigenous traditional knowledge of communities on coping mechanisms is also gainfully applied as communities are well familiar and can provide feedback regarding the contours, drainage patterns of their land and its exposure to vulnerabilities and shocks. They are witness to the severity of disasters and the extent of infrastructure resilience performance in the past. Hence, communities can proactively participate in future planning exercises. This would ensure determination of improved understanding of risks, future margins of safety for design parameter adjustments, education and advocacy, and early warning solutions for DRR.

Notably, it is observed that the communities are more willing to take ownership, for operations and maintenance, of public infrastructure such as water wells, community centres, sanitation facilities, health, and schools. However, they are not keen in taking ownership of rural roads that provide them access to markets, education, and employment opportunities. Community-led performance-based maintenance is an attractive incentive to communities to take ownership of road protection if road maintenance provides them with paid employment/livelihood opportunities at their doorsteps. Hence, strengthening community-led development of APs is an appropriate strategy for providing physical, community resilience, and economic resilience.

This is especially important given that community-led and based development are not driven by community financial resources: in most countries, such public works are funded by governments, and national and international development agencies.

4. Case studies/year of intervention

The selected case studies have been supported by the following agencies:

4.1. India

4.1.1. Mahatma Gandhi national rural employment guarantee act (MGNREGA)/2015

MGNREGA aims at guaranteeing through legal enactment at least 100 days of unskilled manual work every year to each household (ILO, Citation2010). The type of rural public works allowed under MGNREGA are, ‘water conservation, drought proofing (including plantation and afforestation), flood protection, land development, minor irrigation, Horticulture, rural connectivity and land development’ (ILO, Citation2010, p. 4). There are 153.6 million active registered workers (MORD, Citation2022a). MGNREGA employment could be classified as green jobs since they contribute to resilience, climate change mitigation measures such as natural risk management and conservation of biodiversity, and environment-based earnings (ILO, Citation2010; Narayanan, Citation2016).

Given the shortage of qualified technicians for supervision of MGNREGA works in rural areas, a unique innovative effort was launched to train local village youth (10th class pass) for 3 months to become ‘Barefoot Technicians (BFTs)’. NOS, QPs including all Training Modules for Trainers and BFTs were developed (MORD, Citation2015). Subsequently, training of 7000 BFTs in different states was carried out with guaranteed jobs to supervise works.

4.1.2. Prime minister’s rural roads programme (PMGSY)/ 2012-2018

PMGSY aims at alleviating poverty through rural connectivity (MORD, Citation2022b). To date 713,696 km of rural roads have been constructed (ibid). During 2012–2018, pilots for performance-based maintenance contracting (PBMC) of rural road assets were launched on about 500 hundred km of rural roads (M.C. Gupta, personal communication, 25 August 2022). These works enhanced resilience of rural roads, economic activity and community confidence (ILO, Citation2015c).

A web-based ‘Aarambh’ Mobile App for monitoring maintenance of road assets with respect to road inventory and conditions attributes was developed using GIS mapping. This app enabled certification of road maintenance works, contractor activity, oversight, and communication of non-compliance by community-contractors, and inspection reports with photographic evidence of road assets (Gupta et al., Citation2018). Six hundred local engineers trained for using the App.

Another innovation during this period was development of a Pot-hole Repair Tractor-Trailer Prototype (Gupta & Chaturvedi, Citation2018) – an innovation with all required tools fitted on a tractor-towed trolley aimed at pothole repair even in rainy seasons. This prototype does not involve burning of bitumen using large amounts of forest wood. It uses pedestrian vibrating rollers for compaction using cold-mix bitumen emulsions as binder. Cost of acquiring the Tractor-Trailer was found to be 3–4 times lower than traditional heavy equipment (truck, roller, compressor). It proved to be highly useful for small-scale community-contractors at the village level, especially in tropical (high rainfall) and mountainous areas.

As of 2019, all States of India have notified the Rural Road Maintenance Policy (Gupta, Citation2019). The States are now committed to operationalise this Policy and mobilise required funds to meet asset maintenance needs (ibid). Subsequently, 7000 Engineers trained using targeted training modules (ILO, Citation2015a; ILO, Citation2015b).

4.2. Nepal

4.2.1. Strengthening national rural transport programme (SNRTP)/ 2017-2018

SNRTP aims to increase access and reliability of rural roads via: (a) skills training of 4400 locals for, ‘building dry walls, [gabions], stone soling, painting crossing structures, tree planting, and bio-engineering’ (ILO, Citation2019a); (b) capacity building of 400 officials for rural road maintenance. By 2019, a total of 5.4 million paid workdays of employment were created (ILO, Citation2019a). Given the success in yielding resilience results, additional project funds were allocated to further mainstream maintenance of rural roads (World Bank, Citation2020).

4.3. Cambodia

4.3.1. Rural roads improvement project III (RRIP III)/2018

The RRIP III aimed to improve rural connectivity and infrastructure resilience through improving 360 km of rural roads through raising embankment heights, additional drainage works, improving pavement surfacing (ADB, Citation2018). Flood Risk Management Interface (FRMI) technology was used to share information about roads and floods, including flood risk maps (ibid). Climate change scenario analysis based on projected rainfall data for maps creation was used for assessing current and future conditions, risk changes, roads information. The ADB continued to support this approach through funding a project for rural roads improvement in Cambodia post-completion of RRIP III (ADB, Citation2022a).

4.3.2. Japan fund for poverty reduction/ADB (JFPR)/ 2006-2009

PBMC was launched on 75 km of rural roads. An innovative cold-mix not requiring heating of bitumen was successfully piloted including a new surfacing specification ‘Otta Seal’ using uncrushed natural gravel (ILO, Citation2008). Capacity building of local institutions and community contractors was successfully carried out.

4.4. Myanmar

4.4.1. Cyclone Nargis/2008-2009

As per ILO (Citation2009a), tertiary rural infrastructure works in 65 villages. 7,404 people were employed with 80,491 days of paid work, supervised by community committees. Communities built raised concrete footpaths (87.6 km), 25 jetties, 55 foot bridges, 40 latrines. Awareness-raising seminars (employment rights, forced labour, hiring) with over 7000 villagers participating were conducted. Early Recovery Committees (ERCs) were formed and trained; 306 people received vocational training. Response efforts to build resilience using community-based approaches proved highly effective (Kamal et al., Citation2010).

4.5. Bangladesh

4.5.1. ADB/KfW/IFAD supported Coastal Climate- Resilient Infrastructure Project (CCRIP)/ 2013-2019

As per ADB (Citation2011), this Project has 548 km of raised rural roads and 1500 m cumulative length of raised bridges with new adjusted resilience design standards in 12 coastal districts. Twenty-five climate resilient multipurpose cyclone shelters, 88 growth markets, innovative resilient features, 186 community markets, 37 boat landing facilities were built with adjusted resilient infrastructure design standards. NBS including mangroves, vetiver grass, jute textiles were used. Female-led Labour Contracting Societies were formed to do low-end civil works, labour-based road maintenance systems were installed, innovative community-radio were launched in coastal areas in addition to early warning systems. Community-based DRR training was conducted for 1600 beneficiaries. Due to the improved resilient infrastructure, there were improvements in crop sales, total incomes, and food security (Arslan et al., Citation2019).

4.6. Solomon Islands

4.6.1. Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project (CIRP)/ 2003

As per Gupta (Citationn.d.), a judicious mix of employment intensive and local resource-based including NBS are recommended. As per the CIRP Final Report of July 2004 as cited in ILO (Citation2019c), works executed included emergency spot improvements of 103 km roads, preventive maintenance of 85 km roads, repair works of 7 wooden bridges, rehabilitation of 3 schools, 2 community halls, and water supply schemes.

4.7. Analysis

The following key findings and lessons learnt from the analysis of the Dashboard (see, below) emerge (ILO, Citation2009a):

Capacity building of local communities and institutions, LRBA and NBS in participatory planning and low-cost innovations through partnerships have been found to be crucial in strengthening community-led APs.

Although policy and governance factors that contribute to infrastructure resilience are found to be in the ‘Work-In-Progress’ (WIP) stage, the application of LRBA, adjusted design standards/codes, strengthened quality assurance compliance and various capacity-building initiatives of local communities and institutions can positively contribute to resilience (physical infrastructure, community, and economic, see, ). The ‘WIP’ factors (policy, governance) now in place in India, Bangladesh, Cambodia will further consolidate and improve total rural infrastructure resilience in the future. Social audits have been found to be a highly effective tool in quality service delivery, demonstrated in India’s MGNREGA.

For Myanmar, despite no known policies for rural infrastructure and governance factors, community-led innovations and capacity building still contributed to all three types of resilience. Quantitative analysis conducted reveals that this approach positively helped in achieving the desired outcomes most effectively amongst all cases (see, ). In remote areas, since steel bars were not available after Cyclone Nargis, utilisation of local resource-based innovations such as substituting bamboo strips as an alternative to steel reinforcement was used in concrete pavement construction.

The communication APs (local capacity building) support the operational on-the-ground APs (policy, governance, innovations) studied in this paper (see, below).

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The following are the key research findings and recommendations from the analysis of the literature review and model developed for this paper. Notably, these findings are also echoed by the technical papers cited below. Since these findings are based on evidence-based technical reports and impact assessments whereby interventions have been either piloted or successfully upscaled, this implies that the recommendations below are valid and can be referred to as a base for further future research.

There is a positive association between the prevalence of AP factors (evidence-based policy, governance, innovation including local resource-based approaches [LRBA] and nature-based solutions [NBS], capacity building of local communities and institutions), and combined resilience achieved from these factors.

Strengthening of communities and local institutions through capacity building (communications APs) from the inception stage has been found to be a prerequisite for achievement of combined resilience, even in the absence of other AP factors such as evidence-based policy, governance, and innovation. Hence, community-led AP development is crucial.

Skills training (vocational skills and 21st century soft skills) of local communities and governance personnel is necessary for success of operationalising community-led APs to resilient rural infrastructure (Gupta & Gupta, Citation2022).

Training should focus on designing and implementing innovative LRBA and NBS solutions (such as Aarambh mobile app, Barefoot Technicians Training, Vetiver grass, Bamboo), especially for asset management systems, using technology.

Simplified guidelines and Ready Reckoners in local languages on how to construct and maintain resilience public works should be shared with communities and institutional stakeholders for sustained effective APs (Dolidar, Citation2016; ILO, Citation2009b).

Asset management should be foundational and prerequisite of the AP process as it has a direct effect on the physical infrastructure resilience.

Participation of community members from the inception stage of the APs pipeline should be given priority to achieve sustainable resilience.

Adoption of nature-based and employment-intensive solutions, especially those deriving from indigenous knowledge of communities, should be considered over any ad hoc solutions to DRR.

Participatory design of adjustments to standards and codes can help increase the effectiveness of APs (e.g., CCRIP, Bangladesh).

Policy formulation on rural road maintenance and quality assurance should be a pre-requisite for effective mobilisation and allocation of funds (Gupta, Citation2019), to enable the APs discussed in this paper.

Disclosure statement

The Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) reviewed the anonymised abstract of the article, but had no role in the peer review process nor the final editorial decision.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mukesh Chander Gupta

Mukesh Chander Gupta has served as Chief Technical Adviser since 1987 for various infrastructure and social development programmes for the United Nations / UNDP / ILO / World Bank / ADB. He has worked in various post-disaster and post-conflict countries (Cambodia, Solomon Islands, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Maldives, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Tajikistan, Afghanistan), Africa (Tanzania, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Sudan) and Eastern Europe (with United Nations Mission in Kosovo). His areas of expertise include disaster resilient infrastructure development, youth employment, skills development, and sustainable livelihood and community driven recovery initiatives. Mukesh has been Member of various Apex Committees of the Indian Roads Congress for setting of design standards, specifications and codes of practice in the roads sector. He has contributed to many knowledge management platforms through his peer-reviewed Technical Papers. Mukesh holds a B.Sc.(Civil Engineering) degree from Delhi College of Engineering (1973) and a M.Tech (Rock Mechanics) degree from Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi.

Shailly Gupta

Shailly Gupta has served in policy research and project management roles at international organisations such as the International Labour Office, UNESCO MGIEP, UNESCAP and the Brookings Institution India Center. She specializes in the field of education policy, skills development, poverty alleviation, infrastructure development and gender equity. Shailly has contributed a number of Technical Papers and published her maiden novel, “Just how, I wonder?”, in 2020 on the fictional account of a young woman facing sustainable development issues such as climate change-induced disasters. Shailly holds a Master of Public Administration in Science, Technology and Infrastructure Policy from Cornell University and a Master of Education in International Education Policy from Harvard University.

References

- ADB. (2011). Concept paper: Bangladesh: climate resilient infrastructure improvement in coastal zone project (ADB project number 45084). Dhaka: ADB. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/60686/45084-002-ban-cp.pdf

- ADB. (2018). Project climate and disaster risk assessment: Cambodia: Rural roads improvement project III (Report No. RRP CAM 42334). https://docslib.org/doc/7801052/rural-roads-improvement-project-iii-project-climate-and-disaster-risk-assessment

- ADB. (2022a). Cambodia: Rural roads improvement project (Sovereign Project | 42334-013). https://www.adb.org/projects/42334-013/main

- ADB. (2022b). Disaster-resilient infrastructure: Unlocking opportunities for Asia and the Pacific (April 2022). https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/791151/disaster-resilient-infrastructure-opportunities-asia-pacific.pdf

- Arslan, A., Higgins, D., & Islam, A. H. M. S. (2019). Impact assessment report: Coastal climate resilience infrastructure project (CCRIP), People’s Republic of Bangladesh. IFAD: https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/41115388/BD_CCRIP_IA±report.pdf/863f487a-105a-f286-2f2d-2b9a8860cc3b?t=1557928126000

- Dolidar. (2016). Road Maintenance Groups (RMG): Guidelines. Dolidar. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—ilo-kathmandu/documents/webpage/wcms_562124.pdf

- Gupta, M. C. (2019). Creating 1.0 million rural jobs – Maintaining rural roads through local community participation. Indian Highways, 471, 15–27. India: Indian Roads Congress. https://trid.trb.org/view/1581998

- Gupta, M. C. (n.d.). Discussion paper: Road rehabilitation and maintenance strategy in Solomon Islands. Honiara: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—emp_policy/—invest/documents/publication/wcms_434336.pdf

- Gupta, M. C., & Chaturvedi, B. (2018). Development of innovative tractor-trailer for pot-hole repairs on rural roads. Indian Highways, 465, 19–24. India: Indian Roads Congress. https://trid.trb.org/view/1567063

- Gupta, M. C., Chaturvedi, B., Malla, P., & Jha, S. K. (2018). Aarambh the mobile app and web based system: For maintenance of rural roads. Indian Highways, 467, 43–47. India: Indian Roads Congress. https://trid.trb.org/view/1567362

- Gupta, M. C., & Gupta, S. (2022). Skills development challenges in India’s booming roads infrastructure sector. Indian Highways, 50 (2), 28–37. India: Indian Roads Congress https://trid.trb.org/view/1907372

- ILO. (2008). Mainstreaming labour-based road maintenance to the national road network in Cambodia TA 9048: Final Report (October 2008). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—ilo-phnom_penh/documents/projectdocumentation/wcms_122091.pdf

- ILO. (2009a). Emergency livelihood project in response to cyclone nargis in mawlamyinegyun region in Myanmar. https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/wcms-113877.pdf

- ILO. (2009b). Team-based maintenance of rural roads – implementation manual. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@asia/@ro-bangkok/@ilo-kathmandu/documents/publication/wcms_124760.pdf

- ILO. (2010). MGNREGA: A review of decent work and green jobs in Kaimur District in Bihar. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_146013.pdf

- ILO. (2014). Maintenance of rural roads: Policy framework. https://urrda.uk.gov.in/upload/downloads/Download-6.pdf

- ILO. (2015a). Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY): Rural road maintenance training modules for contractors. https://www.ilo.org/emppolicy/pubs/WCMS_431824/lang–en/index.htm

- ILO. (2015b). Rural road maintenance training modules for engineers. https://www.ilo.org/emppolicy/pubs/WCMS_432637/lang–en/index.htm

- ILO. (2015c). Impact assessment study of improved rural road maintenance system under PMGSY. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—emp_policy/—invest/documents/publication/wcms_434255.pdf

- ILO. (2019a). World bank ILO cooperation: Road maintenance as a vehicle for social inclusion and decent work in Nepal. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—exrel/documents/genericdocument/wcms_399641.pdf

- ILO. (2019b). A documentary on piloting community contracting in Himachal Pradesh for rural roads in India. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GT3tBtKH9xQ (Accessed on 22 August 2022).

- ILO. (2019c). ILO - 45 Years in the Pacific, 1974-2019. Fiji: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-suva/documents/publication/wcms_754576.pdf

- Kamal, A., Abel, D., Fan, L., Tang, M., Namasivayam, M., Capistrano, M., Soe, N., Danao, P., Faisal, S., Mark, S. S., Phoeuk, S., Aslim, S., Sabandar, D., & Swe, Z.A, W. (2010). A humanitarian call: The ASEAN response to cyclone Nargis. The ASEAN Secretariat. https://www.humanitarianlibrary.org/sites/default/files/2014/02/a_humanitarian_call.pdf

- MORD. (2015). BFT training materials: Barefoot technicians module. Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India. https://rural.nic.in/en/documents/bft-training-materials

- MORD. (2022a). Dashboard – MGNREGA. Government of India. http://mnregaweb4.nic.in/netnrega/all_lvl_details_dashboard_new.aspx?Fin_Year=2021-2022&Digest=B5DSyTB/eSUSkZd2BpGzbA

- MORD. (2022b). PMGSY: Online management, monitoring and accounting system (OMMAS). Government of India. http://omms.nic.in/

- Narayanan, S. (2016). MNREGA and its assets. Poverty and inequality. Ideas for India for more evidence-based policy. https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/poverty-inequality/mnrega-and-its-assets.html. (International Growth Centre).

- UNESCAP. (2021). Resilience in a riskier world: Managing systemic risks from biological and other natural hazards, Asia-Pacific disaster report 2021. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/knowledge-products/Asia-Pacific%20Disaster%20Report%202021_full%20version_0.pdf

- World Bank. (2020). Implementation completion and results report on a grant in the amount of SDR46.9 million (US$72 million equivalent) and a credit in the amount of SDR18.3 million (US$28 million equivalent) to Nepal for a project for strengthening the national rural transport program (Report No: ICR00005041).: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/704211605461133103/pdf/Nepal-Strengthening-the-National-Rural-Transport-Program-Project.pdf

- World Bank. (2022). Nepal - project for strengthening the national rural transport program (SNRTP) (English). https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/301361468297892179/nepal-project-for-strengthening-the-national-rural-transport-program-snrtp