ABSTRACT

Hazard vulnerability is a characteristic of disaster risks from natural hazards, worsening climate challenges, complex geopolitical governance dynamics, and local development conditions. Comprehensive planning documents often articulate a community’s infrastructure strategies, policies, and capital improvement investments, and are pivotal for sustainable development of cities. This article introduces a new approach for an evidence-based enhanced preparatory technique for comprehensive plans, called Plan I.Q. The framework brings together two recent planning evaluation tools, which use a combination of qualitative assessment and spatial analysis in GIS to develop high-quality integrated plans. The case study presents results from applying the framework during the development of a new comprehensive plan for the City of Rockport in Texas, which incurred heavy damages from Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Results show improvements to plan quality and plan integration across the community’s network of plans, increasing the quantity and quality of infrastructure policies to reduce hazard vulnerabilities.

1. Introduction

Cities across the world are increasingly experiencing adverse effects of climate change and extreme weather events. In the last two decades, the United States has experienced 9 of the 10 costliest Atlantic hurricanes. Hazard vulnerability in communities is a characteristic of disaster risks from natural hazards, worsening climate challenges, complex geopolitical governance dynamics, and local development conditions. The United States National Flood Insurance Program is $20 billion in debt from community flood damages (Report & Research Service, Citation2022). Both the number of claims and claim values have seen an increase over time, despite adjusting for inflation. Notably, the total volume of annual claims has increased by about 2,100 claims per year since 1978 (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], Citation2022).

Aging infrastructure in the United States, along with the rising cost of climate-induced disasters, spurred the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021, which is the largest infrastructure investment in the United States since the New Deal (Tomer et al., Citation2022). The newly passed Act supports the long-term approach for building resilience and budgeted $550 billion of federal dollars in new spending across a breadth of sectors (White House, Citation2021). Additional federally funded infrastructure investments for disaster recovery come through the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Public Assistance Program, which provides grant dollars to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments for their disaster-damaged public facilities (CitationFEMA, n.d). Such targeted investments present a unique opportunity for local governments to align the efficient use of taxpayer funded infrastructure projects to decrease hazard vulnerabilities to benefit all.

Planners, and the planning documents they facilitate, impact infrastructure investment and development through the creation of a wide range of plans, including but not limited to – hazard mitigation plans, city comprehensive plans or master plans, transportation plans, floodplain management plans, parks and recreation plans, downtown or special district plans, among others. Among all these planning documents, comprehensive plans allow local governments to holistically guide and direct the future growth with greater control, transparency, and engagement. There is a correlation between the strength of plans and stricter regulatory standards, quantity of development incentives, and increased infrastructure investments to reduce hazard vulnerabilities, as well as the reduction in disaster damages (Berke, Backhurst, et al., Citation2006; Burby, Citation2006; Lyles et al., Citation2016; Nelson & French, Citation2002). Unfortunately, it is commonplace for local plans to be developed independently of one another by different local organizations, lacking coordination and integration, particularly as it relates to hazard vulnerabilities (Finn et al., Citation2007). This failure to align, coordinate, and integrate a community’s network of plans has been cited as a national and international policy concern by FEMA and the United Nations, among others (FEMA, Citation2013, Citation2015; Godschalk et al., Citation1998; United Nations General Assembly, Citation2015). In knowing this, it begged the question, how can communities develop high-quality, well-integrated plans to reduce hazard vulnerability?

his paper is organized into four sections. The first section introduces comprehensive plans, their importance in community development, and draws connections between comprehensive planning and capital improvements for infrastructure development projects undertaken by local governments. The second section presents literature on the longstanding importance of plan quality and the more recent calls for plan integration and coordination as an essential step to reducing hazard losses. The authors present an approach to do just that through an enhanced preparatory technique, called Plan I.Q. developed from a combination of tools, the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard (PIRS™) and American Planning Association’s (APA) Sustaining Places. The third section illustrates the City of Rockport, Texas, in the United States as an applied case study where these tools were implemented to develop a high-quality comprehensive plan and plan integration to reduce hazard vulnerabilities. This bay city, with some of the highest sea-level rise projections, is a particularly interesting case because in 2017, Hurricane Harvey, a category 4 hurricane, made landfall causing devastating wind damages and triggered the largest rainfall event ever recorded in the U.S. – dumping more than 60 inches in some areas – and subjected Texas to a total of $125 billion worth of property damages. Additionally, the small community of roughly 11,000 residents had previous planning documents focused on disasters, flooding, and infrastructure improvements, and was in the midst of a new comprehensive planning process, which allowed the research team to monitor progress and test the Plan I.Q. technique. The fourth and final section concludes the paper with discussions on the results from Rockport Case Study, the value of Plan I.Q. protocol.

2. Comprehensive planning

Local plans are the most commonly used tool to direct future growth and investments. In Urban Land Use Planning (Berke, Godschalk, et al., Citation2006), the discussion introduces a network of plans. It refers to the set of plans, including but not limited to comprehensive plans, transportation plans, floodplain management plans, economic development plans, hazard mitigation plans, etc. – alongside local or subarea plans such as neighborhood plans, district plans, corridor plans, transit-oriented development plans – as an interlocking system of plans across different geographical scopes with an assumption that they should be consistent with each other (Berke, Godschalk, et al., Citation2006). A comprehensive plan (sometimes also referred to as a general plan or a long-range plan) is meant to be an all-inclusive effort to lay the foundation for future growth policies and capital improvement projects, particularly for infrastructure. It is an attempt towards establishing sustainable long-term development decisions designed to be adopted by law. Comprehensive plans are representative of the community’s values and preferences and a guide for achieving their goals and aspirations. Though, they are highly personalized, and the contents of comprehensive plans differ from community to community.

Typically, comprehensive plans contain some combination of the following elements, often coined as ‘traditional themes’ – land use (both existing and future), housing, community facilities, infrastructure, parks and recreation, and transportation – each, often covering goals and policies falling under these categories. More communities are re-thinking and re-organizing comprehensive plans into ‘non-traditional themes’. Non-traditional themes allow creative overarching themes (such as resilience, inclusive community, responsible growth, complete neighborhoods, strong economy, social equity, etc.) that look at holistic improvements (Rouse and Piro, Citation2022). Elements from traditional themes or chapters interact under these overarching themes to create an interwoven framework of mutually supportive policies. This systems thinking-based approach recognizes that cities are complex systems with interdependent and interlaced networks of subsystems (Rouse & Piro, Citation2022). It reinforces the adaptive approach in planning across sectors, facilitates resilience, and strengthens plan implementation. Planning efforts typically need inputs from several agencies, government bodies, and community stakeholders, and span across several months.

2.1. The importance of comprehensive plans for communities

Since a comprehensive plan directs the future growth and investments, as a best practice measure, it should act as an overarching plan to serve as a policy framework for all other plans developed for a jurisdiction (Rouse & Piro, Citation2022; Duerksen, Dale and Elliot, Citation2009). Comprehensive plans can also act to organize and compile strategies, policies, and projects spread through different time-horizons. Additionally, local planning efforts are typically geographically focused, which is considered the most promising long-term solution to reducing hazards vulnerability (NNational Research Council [NRC], Citation2012, Citation2014).

Plans with land use policies, such as comprehensive plans, can positively impact regulatory standards, development incentives, and infrastructure investments to reduce hazard vulnerabilities, which can also reduce disaster damages (Berke, Backhurst, et al., Citation2006; Burby, Citation2006; Lyles et al., Citation2016; Nelson & French, Citation2002). Infrastructure planning has become central in land use plans and comprehensive plans as communities tackle the growing need to address sustainability and climate challenges (Elmer & Leigland, Citation2013). Local governments use comprehensive plans to guide capital improvement plans (CIP) and capital budgets, which are pivotal for implementing infrastructure projects (Bowyer, Citation1993). Additionally, comprehensive plans can play a significant role in communicating long-term infrastructure investment decisions by allowing local governments to be proactive, predictable, and fair in allocating infrastructure financing (Sullivan & Lester, Citation2005). Implementing measures like development regulations direct infrastructure investments by private developers towards the vision established by the comprehensive plan.

3. Plan quality and plan integration

Despite the benefits of comprehensive plans, there still remain few tools to assess plan quality against professional best practice standards (Godschalk & Rouse, Citation2015). Additionally, even if the comprehensive plan is high quality – with more robust policy tools, regulations, and infrastructure investments – they may not be coordinated, implemented, or even considered across other local planning documents because they are often developed independently of one another by different organizations (Finn et al., Citation2007). This is particularly concerning with increased urgency to act to reduce hazard vulnerabilities and climate-induced impacts. The following describes the literature on plan quality and plan integration and two recent tools developed to standardize and professionalize planning best practices.

3.1. ‘Sustaining places’: a plan quality assessment tool

All plans are not created equal. The significance of local development plans and their evaluation can quickly become complex and extensive – based on the goals and outcomes intended – and remains a challenging issue to address in both academic and practical settings. Over the years, evaluation methodologies developed by Baer (Citation1997) and Norton (Citation2008) have shown how plan scores can range dramatically based on the framework and approach. While these focus on evaluating general or local comprehensive plans, other tools exist for evaluating specific plans – for Hazard/Disaster Mitigation Plans by Berke, Smith, et al. (Citation2012) and Berke, Roenigk, et al. (Citation1996); for Housing Recovery Plans by Van Zandt et al. (under review); and for Green Infrastructure Plans by McDonald et al. (Citation2005). Plan Quality assessment tools, therefore, help city and regional staff to analyze the sustainability of planning efforts, effectiveness of the proposed strategies and policies, identify potential gaps, and plan for continual improvement.

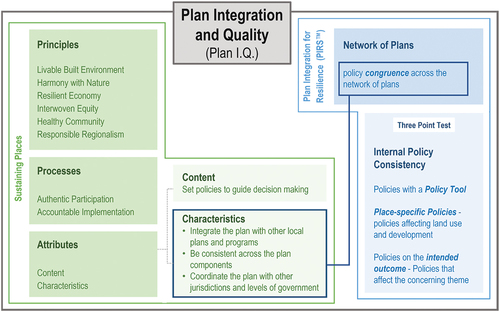

In 2010, the American Planning Association (APA) launched the Sustaining Places Initiative and established the Sustaining Places Taskforce to explore the role of comprehensive plans in helping local communities achieve sustainable development outcomes. The task force’s work culminated in the development of the Comprehensive Plan Standards for Sustaining Places, published as the Planning Advisory Service (PAS) Report Sustaining Places: The Role of the Comprehensive Plan (Godschalk & Anderson, Citation2012). In an effort to translate research on plan quality assessment into a useful framework that local communities can use, APA formed a working group in 2015 to design a plan quality rating tool presented in PAS Report 578, also known as Sustaining Places: Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans (Godschalk & Rouse, Citation2015), with a focus on sustainability. The Sustaining Places tool standardizes and scores plans based on three categories: principles, processes, and attributes. A brief description of these comprehensive plan standards is presented in below:

Table 1. Sustaining places: the role of the comprehensive plan (Godschalk & Anderson, Citation2012).

The comprehensive plan policies and language is assessed based on a set of best practice measures described within the tool. Each measure is then assigned a score based on the breadth and depth of its inclusion in the plan. The scoring criteria yields one of the five possible scores:

Not Applicable – does not penalize the plan rating

Not Present − 0 points

Low − 1 point

Medium − 2 points

High − 3 points

The procedure results in an overall score based on how the plan performs on each of these standards. The Sustaining Places framework is proven to be a progressively holistic approach to comprehensive plan quality assessment and is widely accepted by practitioners for evaluating local comprehensive plans.

3.2. Plan integration through PIRS™

More recently, planning researchers and practitioners have expressed growing concern over the lack of consistency in policies across a community’s network of plans (Berke, Yu, et al., Citation2019). Plan coordination to reduce fragmentation in local planning has been cited as a critical policy concern to address hazard vulnerabilities (FEMA, Citation2013, Citation2015; Godschalk et al., Citation1998; United Nations General Assembly, Citation2015). Occasionally, comprehensive plans, as the community’s overarching guidance document, refer to other documents in a community’s network of plans, but the degree to which they are truly integrated and aligned remains unclear in the absence of an assessment tool. When policies and projects across the network of plans in an area are incompatible, it exacerbates the vulnerability (Malecha, Masterson, et al., Citation2019). Tools such as FEMA’s Plan Integration Tool focus on coordination – evaluates links of people and organizations, responsible parties, agencies, or programs (FEMA, Citation2015). However, plan integration must go further to cross-examine the impact of inter-linked policies across the network of plans. Additionally, FEMA now emphasizes the integration of land use tools as a key strategy to mitigation planning (FEMA, Citation2013). In an effort to bridge the research gap, in 2015, a team of researchers developed a plan integration scorecard (Berke, Newman, et al., Citation2015), the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard (PIRS™) (Malecha, Masterson, et al., Citation2019). The first-of-its-kind tool, PIRS™, evaluates often disparate policies, actions, and initiatives across the plans and fills a critical research gap.

PIRS™ entails assessment of existing plans that may directly or indirectly impact development and community capital investments (Berke, Yu, et al., Citation2019; Yu, Brand, et al., Citation2020; Yu, Malecha, et al., Citation2021). Prior to PIRS™, the planning field lacked the ability to spatially evaluate whether policies were contradictory or complementary in different geographic areas of a city and across a community’s network of plans. PIRS™ evaluates how policies impact a particular geographic extent – such as a neighborhood or a city – and generates a compatibility measure on whether these policies align or conflict (Berke, Kates, et al., Citation2021). For practitioners, it presents a dynamic tool to visualize incongruity within plan policies exacerbating existing (or new) issues. Owing to the robust approach of PIRS™ in evaluation of the network of plans and reinforcing hazard resilience, APA launched an online course for planners and allied professionals to learn PIRS™ through the APA Learn website.

To administer PIRS™, first it requires extraction of policies or action items for applicability from each of the plans within the network. Each policy or action item should consider questions within the ‘three-point test’:

What is the policy tool? (e.g., capital improvement project),

Where does it play out? (e.g., along Main Street), and

Does it affect the concerning thematic issue? (e.g., flood hazard)

The three-point test reveals and articulates specificity and implementability of a policy. Next, planners score the policies based on the intended outcome; if the policy has no impact (score = 0), negative impact (score = −1), or a positive impact (score = +1). The evaluator can then see the individual and cumulative impact of policies across geographies. The resultant from the overlay produces an overall composite score at a particular geography or planning district revealing areas of conflict.

The three-point test is key because it provides a critical look at the merit of each policy’s contribution to the thematic issue. For instance, a transportation policy to provide a proposed collector roadway connection in a community could be problematic if the geographic area also includes a floodplain (such was the case in Norfolk, where we realized a key roadway would be the only way in and out for many residents, revealing the need to raise the roadway) (Malecha, Masterson, et al., Citation2019).

3.3. Connections between the two tools

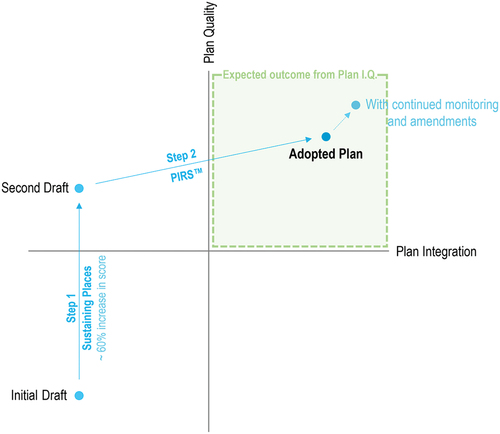

Little is known about the plan quality of comprehensive plans compared to best practice standards (Godschalk & Rouse, Citation2015), as well as their integration across other plans that influence land use and development created by different organizations in a community (Finn et al., Citation2007; Hopkins & Knaap, Citation2018). This gap in the literature necessitates a thoughtful approach to combining these relatively new assessment tools as a way to understand contradictory policies that may unintentionally increase hazard vulnerabilities. There are natural alignments and connections between Sustaining Places, which provides depth, and PIRS™, which provides breadth and horizontal alignment across planning efforts (see ). For instance, within Sustaining Places, the attributes describe key characteristics for high-quality plans, such as integrating the plan with other local plans, consistency across plan components, and coordinating the plan across jurisdictions. While Sustaining Places includes plan integration as an important metric, it does not specifically articulate how this can and should be done. PIRS™ provides the mechanism to achieve such higher-quality plan characteristics. Additionally, PIRS™ focuses on the policies within planning documents. The policies are the result of the Sustaining Places principles. Therefore, the policies within the comprehensive plan are evaluated for plan quality with Sustaining Places and evaluated for their congruence and impact on resilience using the three-point test within PIRS™. Combined as Plan I.Q., this new approach ensures enhanced planning capacity, high stakeholder engagement, opens opportunity for inter-agency dialogue, and enables high-quality, well-integrated plans focused on reducing hazard vulnerability.

3.4. Plan I.Q

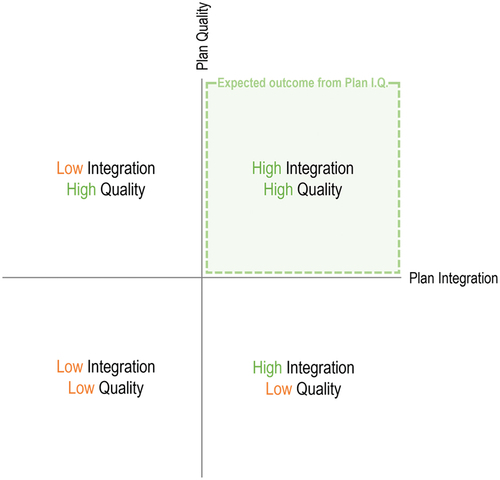

We applied the comprehensive plan quality assessment tool, ‘Sustaining Places’, and PIRS™ in combination to understand the ‘plan integration’ and ‘plan quality’, or what we are calling Plan I.Q. Plan I.Q. is an enhanced technique that intends to better prepare communities for future challenges. To achieve high Plan I.Q., plans should have internal policy consistency, along with policy congruence across the network of plans (Malecha, Masterson, et al., Citation2019; Yu, Brand, et al., Citation2020). More often than not, these dimensions are not correlated. A plan can be high quality and designed to work in isolation, or it can be well integrated but lack structure and adequate policies.

The relationship between Plan Integration and Quality for the terms of Plan I.Q. is illustrated in . Plans in the bottom left quadrant have low integration and quality. Examples can be relatively superficial stand-alone plans that are narrow in focus and have little to no cross-linkage to other plans within the community. In addition, they tend to have shallow coverage of applicable topics or themes and avoid specificity. The strategies overlook community needs and have very few policies pushing the plan forward.

Plans in the bottom right quadrant have high integration but low plan quality. Plans falling into this category fail to provide a robust structure within the plan. The comprehensive plan happens to be of lower quality when it does not effectively cover the range of relevant topics. The plan may not adequately address certain themes but does contain policies in place integrating across the network of plans that advance the goal, in this case, reduction of hazard vulnerability.

Plans in the top-left quadrant have low integration but high quality. This may happen when a comprehensive plan is arranged in a functional structure that effectively addresses issues through best practice principles, has a constructive plan process, and a robust implementation strategy. The plan may still lack a holistic consideration of how development may impact a thematic issue such as hazard vulnerability. If the policies are in misalignment with the network of plans, they can exacerbate vulnerability. For instance, a comprehensive plan promoting a mixed-use, dense walkable district is an exemplary practice; however, in the floodplain or Special Flood Hazard Zone, it intensifies flood vulnerability.

A high-quality, well-integrated plan would get placed in the top-right quadrant (see ). Such plans are rich in content, specific in policies, and contain strong implementation strategies. Taking a plan from high integration and low quality to high plan I.Q. is much more challenging than taking a low integration high-quality plan to high I.Q. Low-quality comprehensive plans generally have low stakeholder buy-in, are more likely to be ‘shelved’ and require significant planning capacity to be actualized while non-conformance in high-quality plans can be managed through plan amendments and updates within the network of plans. Policies that reduce hazard vulnerability – in the network of plans – can be built into the comprehensive plan and woven across the planning documents to strengthen integration.

4. Methods

We tested the use of the two tools during the development of a new comprehensive plan. Plan I.Q. is a multi-step process; to prepare high-quality, well-integrated plans in the midst of a planning process or plan update, we took the following steps. It is also iterative with respect to comprehensive plan draft improvements. Prior to administering Plan I.Q., a draft plan must be ready for assessment. All relevant local and regional plans – the network of plans – should also be gathered. The first step is to obtain the draft comprehensive plan developed by an outside planning team. The draft is then evaluated using the Sustaining Places plan quality assessment tool to identify gaps across chapters, and determine the depth and quality of the content. Since this is a quasi-quantitative step in the process, we suggest a panelist approach consisting of two or more members. The scores obtained through individual panel members should then be averaged to obtain final scores. Next, the results are presented to the planning team which makes revisions and improvements further validated by city staff and other stakeholders.

The second step uses PIRS™ to test the coordination and integration of the comprehensive plan across the network of plans. The network of plans is examined closely to isolate the policies and elements affecting the planning region. The effects of these are then mapped spatially using GIS, and the planning districts are assigned scores on whether they reduce, exacerbate, or do not affect the vulnerability in each of the identified planning districts. A detailed methodology and step-by-step process for applying PIRS™ is illustrated in the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ Guidebook (Malecha, Masterson, et al., Citation2019). Again, the draft comprehensive should be revised and improved upon by professional planning staff and city staff and later validated by the public after administering this step.

The third step is generating a list of conflicting policies that should be changed or amended across the network of plans to solidify the congruence. These policy amendments may be communicated to relevant agencies to open bilateral dialogues to strengthen community positioning and regional resilience. While this is suggested best practice, we acknowledge that it is highly subjective and effective inter-agency communication is often driven by several external factors.

For our case study in the City of Rockport (Texas), the research team obtained relevant planning documents – including the draft plan – from the professional planning staff. Two members of the research team then applied the Sustaining Places tool to assess the plan quality of the initial draft. Following that, the results were sent to the planning team, for the first round of revisions. During this step, several stakeholder consultation meetings were organized, and their inputs were included iteratively.

Parallelly, the research team accessed the network of plans in Rockport and carried out the scoring process for PIRS™. Several sources such as the official county website, official city website, chambers of commerce website, and websites of other local and regional organizations were scouted to generate the network of plans. Additionally, the city planning staff was interviewed to verify and complete the network of plans. The sources for the documents within the network of plans are in .

Table 2. Sources for documents within the network of plans.

Most of the spatial data was obtained through the U.S. Census TIGER/Line Shapefiles (Census Bureau, Citation2019). The floodplains were obtained through FEMA National Flood Hazard Layer database (NFHL, Citation2019) with missing data provided by the City of Rockport. The research team identified the planning districts whereupon the impacts of policies within the network of plans were assessed and scored. The scores revealed both the strengths and inconsistencies across the network of plans. Plans were first illustrated individually. Later, the arithmetic sum of individual plan scores within each district was generated and mapped to create a composite score which represented the level of physical vulnerability arising due to conflicting policies within the network of plans. These results were again forwarded to the planning team to make the final round of revisions and amendments in the comprehensive plan draft. The scorecard generated during this process was also shared so as to provide a list of policies and their resulting impact on planning districts. The recommendations were folded into a comprehensive plan document effectively concluding the planning process.

As a last step, the research team generated a list of recommended policies to change or amend across the network of plans. Finally, we indicated all policies within the final (adopted) comprehensive plan that were integrated and coordinated across the community’s network of plans in the comprehensive plan’s implementation table.

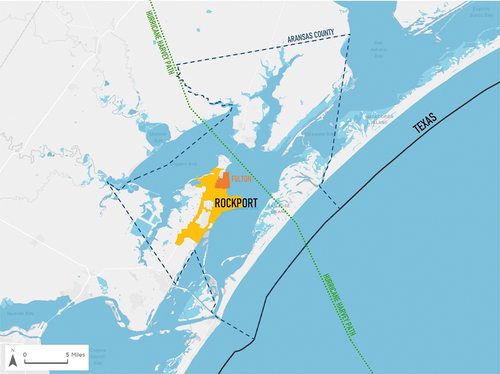

4.1. Rockport, TX: a case study

The City of Rockport, Texas, a small city of 11,000 residents by the 2021 Census estimates, is a coastal tourist destination and fishing community in the Texas Coastal Bend Region of the United States (see ). In August 2017, Hurricane Harvey made landfall as a Category 4 storm causing significant damage across the city and state. The storm is the largest rainfall event ever recorded in the U.S. – dumping more than 60 inches in some areas – and subjected Texas to a total of $125 billion worth of property damages. In Rockport, the high winds caused damages to infrastructure with 12 days of power outages, 50% of all structures were damaged, and 25% of structures were substantially damaged or unrepairable (Walters, Citation2018). The community lost all multi-family housing, the City Hall, the County Courthouse, and six of the 12 hangars within the Aransas County Airport. Even before the hurricane, city staff noted infrastructure concerns around the central business district, where high tide waters backup sewer systems and flood streets. Sea level rise projections indicate significant impacts to this bay community in the future. Up until this point, the city had been proactively planning with more recent planning documents focused on disasters, flooding, and infrastructure improvements. Soon after the hurricane, the county coordinated the development of a long-term recovery plan. Following this effort, city staff saw a growing need to improve infrastructure and coordinate infrastructure investments by updating their comprehensive plan, which was more than 20 years old. Due to these factors, the research team followed the city’s new comprehensive planning process, monitored progress, and tested the Plan I.Q. tool on its ability to improve plan quality and plan integration to reduce hazard vulnerabilities.

One year after the hurricane, the city began a comprehensive planning process. Two key local agency staff who were associated with the comprehensive planning process. Amanda Torres, chief planner and certified floodplain manager, served as the main point of contact. Michael Donoho, Torres’ supervisor, and Director of Building, Development and Public Works, was informed throughout the plan evaluation process and provided input in guiding development of the policy recommendations for the comprehensive plan. After developing the first draft, the planning team assessed the plan’s quality using the Sustaining Places tool. For the purposes of this paper, we describe the summarized results of the principles because of the direct language related to plan policies, as opposed to the processes and attributes, which have little impact on infrastructure policies. Of the six principles, none scored more than 50% of the maximum possible score on the first draft, with Resilient Economy scoring the highest (48%) (see ). The results from the assessment helped identify gaps to improve the quality of the comprehensive plan. For instance, the initial draft lacked locational specificity for many strategies or did not define specific hazard zones and provided very few mitigation policies to enhance resilience in known hazard zones. Some examples from the first draft directly affecting infrastructure development or capital improvement projects which were identified for improvements during subsequent revisions are mentioned below:

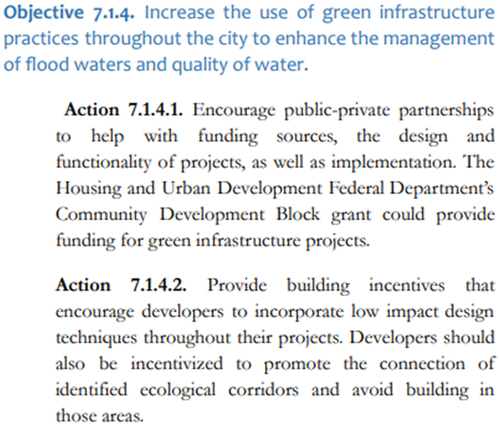

While the plan mentioned multi-modal transportation as a goal or focus area, it did not explicitly explore specific streets (or sections thereof) for infrastructural development where multimodal networks can be enhanced, expanded, or integrated within a regional geography.

Policies supporting development and maintenance of Green Infrastructure in the first draft lack the use of strong, precise, and direct language. Additionally, including specific incentives (such as tax incentives, density bonuses, TIRZ, etc.) would embolden the plan for implementation.

Example from plan draft: The objectives and action items in figure below are samples of language that lacks specific interventions, policy tools, or specific location or area where the proposed recommendations.

The plan needs stronger post-disaster recovery and mitigation strategies including maintenance of storm drainage infrastructure and development of other hard infrastructure for storm surge and flood mitigation-related infrastructure, found to be lacking in the first draft.

The plan intends to upgrade infrastructure and facilities in older and substandard areas. However, it does not reflect in the action items and misses on identification of outdated and substandard infrastructure across the city.

Regional funding agencies are suggested as potential sources; however, the plan does not mention building upon regional projects to derive benefits for local residents.

The plan does not explicitly address the aim of floodplain management, reduction of development activities focused on areas lying within the floodplain (spatially or otherwise).

The plan does not address encouraging climate change adaptation in any capacity.

Table 3. Rockport comprehensive plan quality scores.

With the aid of Sustaining Places assessment, the planning team added policies to provide specificity in transportation recommendations, encourage wetland preservation, increase the use of green infrastructure, improve natural water retention, strengthen the coastal shoreline, and develop conservation overlay land use regulations to ensure critical habitats were protected. After the revision, the second draft was scored highly in all the categories of Sustaining Places. shows results for the first draft and the revised second draft across categories of best practice standards.

Enabled with this higher quality second draft, the city utilized the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ tool to determine the alignment of policies across its network of plans. The city staff worked with researchers from Texas A&M University to evaluate Rockport’s network of plans in mid-2019. The network of plans for Rockport consisted of six plans:

Rockport Strong: City of Rockport Comprehensive Plan 2022–2042 (2020) (City of Rockport, Citation2020)

A Vision for Rockport: A Master Plan for the Heritage District and Downtown Rockport (2006) – HDMP (City of Rockport, Citation2006)

Rockport Heritage District Zoning Overlay Code (2014 update) – HDZO (City of Rockport, Citation2014)

Aransas County Long Term Recovery Plan and Report (2018) – LTRP (City of Rockport, Citation2018)

Aransas County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Action Plan (2017) – MHMP (City of Rockport, Citation2017b)

Aransas County Multi-Jurisdictional Floodplain Management Plan (2017) – MFMP (City of Rockport, Citation2017a)

In addition to the six documents in Rockport’s network of plans, recommendations from APA’s Recovery Planning Assistance Team Report (RPAT) were also considered. Rockport received APA Foundation’s 2018 Disaster Recovery Grant for a Recovery Planning Assistance Team. The RPAT team conducted a preliminary site visit in January 2019 with an aim to assist in revitalization, resilience and recovery of Downtown Rockport (City of Rockport, Citation2020). RPAT’s study focused on the Austin Street Corridor in Downtown Rockport and was included in the comprehensive plan.

The PIRS™ evaluation of the network of plans provided an insight into the spatial relationships between Rockport’s existing plans and policies, and their resulting impact on vulnerability – individually and concurrently. Overall, the plans across the network scored high (Malecha et al., Citation2020). The draft comprehensive plan, heritage district and downtown master plan, and the heritage district zoning overlay code scored the lowest. Across all plans, there were weaker scores in the downtown district and adjacent districts where infrastructure needs are a pressing concern. The emerging patterns revealed opportunities to achieve higher integration in the draft Rockport Strong comprehensive plan, to accompany the higher quality attained through Sustaining Places assessment, potentially placing this plan in Quadrant 1 (see ).

4.1.1. Infrastructure policies across the network of plans

Rockport’s network of plans presented several avenues of integration across planning sectors within the comprehensive plan, particularly for infrastructure policies. After PIRS™, the draft comprehensive plan was revised and improved upon by professional planning staff and city staff and later validated by the public. The gaps identified within the infrastructure and community facilities sector through the Sustaining Places tool in the initial plan draft were also bridged by cross-referencing other autonomous plans and, in some cases, adopting or building upon the policies in the network of plans. These adjustments are reflected in the action items of the final comprehensive plan. Rockport’s comprehensive plan focuses on themes rather than traditional planning sectors. Infrastructure policies are hence interspersed throughout the plan.

describes the infrastructure-specific best practices of Sustaining Places, infrastructure-specific policies identified through PIRS™ across the network of plans, and the infrastructure-specific policies and strategies within Rockport’s final comprehensive plan.

Table 4. Infrastructure-specific policy alignment for Rockport, TX.

4.1.2. Results

One of the six guiding principles of the Rockport Strong Comprehensive Plan is ‘Responsible Growth’ that focuses on infrastructure development across the community. In addition to actionable recommendations, other initiatives and policies were included in the language of the comprehensive plan to solidify its congruence. Also, case studies of communities with similar characteristics were used as success stories of recommended strategies. Notable infrastructure initiatives that emerged as a result of Plan I.Q. are:

Innovative practices – such as Green Infrastructure (GI) and Low Impact Development (LID) practices both at site level and community level to regulate future development and mitigate the effects of future disruptions.

Development constraints and systems approach – by avoiding new development in flood-prone areas and within floodplains, reducing or limiting impervious land cover, fill restriction, and strategies to manage water where it falls.

Management of flood waters and quality of water – by increasing the use of green infrastructure practices throughout the city.

Improved Regional Coordination – mitigating coastal erosion and strengthening the coastal shoreline with the Aransas County Navigation District.

Minimize Environmental Impacts – Goal 8.1. Ensure that all infrastructure elements meet existing and projected demands in a manner that will minimize environmental impacts.

Adaptive Reuse – By using existing infrastructure and redeveloping infill sites or greyfields.

The process carried out for the Rockport Strong plan took a draft that was initially in low integration and low-quality quadrant to a low integration high-quality draft by passing it through the Sustaining Places tool, and ultimately parked it on the high integration high-quality quadrant post administration of PIRS™ protocol (see ).

Administering Plan I.Q. for the City of Rockport helped the planning team to develop a deepened understanding of the newly drafted comprehensive plan’s impact on the community’s vulnerability to flood hazards. According to Torres, PIRS™ served as a ‘filter to see how all the individual plans aligned’ and enabled the city to ‘internalize resilience’ across multiple sectors of disaster recovery. These findings were then used by the city as the basis for readjustment of recommendations to further improve the comprehensive plan’s policies before adoption. Measurable impact on outcomes was observed in planning capacity and plan features by the research team. Torres observed that the process increased the capacity of local officials to foster the development of an overarching policy framework that integrated resilience across all chapters (development, environment, housing, transportation, economy, facilities) of the new comprehensive plan. She maintained that the integrated policy framework serves to educate elected officials, agency staff, interest groups, and the general public about how diverse sectors of the community (tourism, heritage, hazard mitigation, environment) can work together to foster resilience. It also serves to guide city staff and elected officials in day-to-day decision-making by helping them stay on track toward achieving the long-range vision of resilience articulated in the plan. Due to COVID-19, some implementation actions were put on hold temporarily; hence, other impacts such as investments and grants receipts, milestones achieved, and vulnerability assessments are yet to be observed. A summary of outcomes observed thus far is presented (Berke, Masterson, et al., Citation2020):

4.1.2.1. Planning capacity

Stronger social ties observed across organizations

Four public hearings with over 200 residents organized

Thirteen advisory committee members served as key persons

Five plans evaluated and integrated

Silver Achievement Award received in Resiliency Planning from the Texas Chapter of the American Planning Association

4.1.2.2. Plan features

Resilience-centered policy framework

Innovation in implementation action matrix with plan integration column

Seventy-three best practices policies adopted from the plan network

Forty-eight implementation actions referencing other plans within the network of plans

5. Discussion

The combination of evaluating plan quality and plan integration ensures minimization of conflicts and elimination of contradictions while leveraging strengths across the network of plans. It sets forth an analytical framework that focuses on integrating best practice and planning theories on the quality and quantity of policies, maximizing their potential for implementation. The Plan I.Q. process can help practitioners identify specific topics and areas that require further research or strategic intervention to meet community goals. While Plan I.Q., discussed in this paper, specifically aims to improve hazard vulnerabilities during a comprehensive planning process, the concept can be adapted for sector specific (housing, transportation, etc.) plans as well.

Rockport’s case study presents the practical application and testing of the Plan I.Q. process, which significantly elevated the quality of the new comprehensive plan, as well as the integration across the community’s network of plans, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitatively, the research team proposed adding an additional ‘Plan Integration’ column in the implementation table of the comprehensive plan. This column identified the plan (within the network of plans) with which a particular action item was integrated. City staff stated the additional column and reference to other planning documents increased political will to prioritize and implement integrated strategies. Quantitatively, an overall increase of about 60% (or 24% points) in Plan Quality scores was observed between the initial draft and the revised draft after assessing through the Sustaining Places framework.

City staff utilized PIRS™ after the second draft of the comprehensive plan, using the insights to amend incongruent policies. The connection to the county hazard mitigation plan and long-term recovery plan was important to the City in terms of motivating commitment to carry out a comprehensive plan. One resident, after reading through the comprehensive plan, said, ‘I was involved with the Long-term Recovery Plan, and I see it discussed here. Everything we worked on in that is not lost and is built on.’ Another active participant on the recovery plan representing the county government noted that ‘after the countless hours we put in … I am thankful to see that our work matters.’ In this case, Plan I.Q. acted as a catalyst to drive a high-quality comprehensive plan which in turn identified and proposed amendments for unfavorable conflicting policies in other plans within the network of plans. The other planning documents most likely lie on a continuum of plan quality. Lower plan quality of other constituents in the network does not lower the plan quality of a comprehensive plan, but rather improves it by yielding higher coordination, spatial specificity, and conflict identification. It goes to show that PIRS™ can improve the quality of the comprehensive plan, and also advance the network of plans a step further towards achieving resilience. Specifically, the paper demonstrates the value of the process as it relates to infrastructure investments to reduce hazard vulnerability.

5.1. Limitations & implications

This study has some limitations. The two tools used, Sustaining Places and PIRS™, to score comprehensive plans and network of plans are qualitative in nature. Depending on who scores plans, there is somewhat subjectivity in the precise scores given. For research purposes, it is important to validate work with intercoder reliability. For practice, the subjective scores may limit comparability across different communities. Despite this, the discussions city staff have as they determine scores and the impacts of policies within plans outweighs the drawbacks. Additionally, to further understand the impacts of Plan I.Q. and the benefits of combining the two tools, there are benefits to testing it across different communities in the midst of their comprehensive planning processes. The research team has thus far tested the Plan I.Q. in small communities. The research would benefit from the application across various size communities, regional contexts, and types of hazard vulnerabilities to ensure scalability and generalizability.

The implications of Plan I.Q. are a more systematic approach for local governments, planning practitioners and other professionals during the comprehensive planning process to improve the quality and integration of policies across a community’s network of plans. A high-quality comprehensive plan reflects the community vision and encourages institutional and individual buy-in the implementation process, thereby resulting in an actualized plan.

5.2. Conclusion

Planners are equipped with the essential tools and knowledge to navigate through the complex issues facing communities today but are also presented with equally challenging constraints. Making trade-offs, working toward inter-agency coordination and acquiring political support are crucial to effective infrastructure projects that mitigate hazards. We argue that by thoughtfully evaluating plan quality and plan integration, specifically, combining the tools ‘Sustaining Places’ and PIRS™, communities can reduce hazard vulnerabilities. Furthermore, plans with actionable, specific, and geographically tethered strategies are more likely to be implemented, especially for capital improvement programs requiring external funding. ‘Sustaining Places’ and PIRS™ are linked by spatially identifiable policies across a community’s network of plans. The case study sets the stage to illustrate how Plan I.Q. drives a high-quality comprehensive plan to be ‘all-inclusive’ and holistic, aligned with initiatives and strategies across a community’s network of plans.

Author contributions

Masterson conceived of the presented idea and developed the theory. Malecha, Katare, and Thapa performed the computations. Thapa, Masterson, and Malecha worked closely with the City of Rockport to test the analytical process. Masterson, Katare, and Thapa verified the analytical process. Berke encouraged Masterson to investigate and supervised the findings of this work. Berke conducted follow-up interviews with the city of Rockport to document additional outcomes. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this article is based on work supported by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (Grant #0031369). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Disclosure statement

The Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) reviewed the anonymised abstract of the article, but had no role in the peer review process nor the final editorial decision.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jaimie Masterson

Jaimie Hicks Masterson is director of Texas Target Communities at Texas A&M University, a high impact service-learning and engaged research program that works alongside low capacity communities to plan for resilience. She is author of Planning for Community Resilience: A Handbook for Reducing Vulnerabilities to Disasters and Engaged Research for Community Resilience to Climate Change. She is the engagement coordinator Institute for Sustainable Communities and the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard project funded by the Department of Homeland Security and a part of the Center for Coastal Resilience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Anjali Katare

Anjali Katare is a young professional with a Master in Urban Planning from Texas A&M University (USA) and Bachelor in Architecture from NIT Bhopal (India). Currently working as a Planner and Economic Analyst, she also engages as a researcher with Texas Target Communities at Texas A&M University. Anjali enjoys working on projects at all scales, from a small residential design to long-range planning for communities. She aims to address hazard vulnerability, climate impacts, and socio-economic challenges through data-led community-driven research. Over the years, she has worked on a range of projects across architecture, planning, real estate and public health fields. Anjali is also co-founding member of Vastukul, an ed-tech platform geared towards making design and planning education accessible and affordable in India.

Jeewasmi Thapa

Jeewasmi Thapa is the Senior Program Coordinator of Texas Target Communities, a high-impact service-learning and engaged research program at Texas A&M University(TAMU). She works alongside underserved communities to provide tailored planning support grounded in the local context and informed by interdisciplinary teams skilled at addressing land use planning, development management, and a host of civic, environmental, and economic challenges. As a certified planner, she designs inclusive community engagement processes and develops plans to fold and infuse data-driven strategies and best practices to address community-identified needs. She is also an engagement specialist for Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center at TAMU.

Matthew Malecha

Dr. Matthew Malecha is an instructional assistant professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning at Texas A&M University and a faculty fellow with the Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center. His research focuses on community resilience to natural hazards—especially the roles of plans, policies, and regulations, and their interactions with underlying social and spatial characteristics. Spatial plan evaluation and the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ (PIRS), which Malecha helped develop during his graduate studies, are central to this work. He also recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Community Resilience Program, where he explored community understanding and expectations of resilience, adaptation, and sustainability planning, investigating areas of overlap, barriers to action, and opportunities to improve effectiveness.

Siyu Yu

Siyu Yu is an assistant professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning and a core faculty with the Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center at Texas A&M University. Her experience spans land use, plan integration, and resilience issues in the United States and the Netherlands, and Japan. Much of Dr. Yu’s current research focuses on the development, application, and extension of the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard TM (PIRS) evaluation methodology. The aim of this research is to better understand relationships among the network of land use and development plans and policies, and social and physical vulnerability to hazards and climate change. Her research has been published in the Journal of the American Planning Association, Journal of Planning Education and Research, Landscape and Urban Planning, Sustainable Cities and Society, and the Journal of Environmental Planning and Management.

Philip Berke

Philip R. Berke is a Research Professor, Department of City & Regional Planning; and Director of the Center Resilient Communities and Environment, Institute for the Environment of the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. Berke’s research centers on community resilience to hazards and climate change with a focus on theory, methods and metrics of community planning and implementation. He has published over 100 peer reviewed articles and book chapters, and 10 books. He is the lead co-author of an internationally recognized book, Urban Land Use Planning (5th Edition), which focuses on integrating principles of sustainable communities into urban form, and co-author of a book, Natural Hazard Mitigation: Recasting Disaster Policy and Planning, which was selected as one of the “100 Essential Books in Planning” of the 20th century by the American Planning Association Centennial Great Books.

References

- Baer, W. C. (1997). General plan evaluation criteria: An approach to making better plans. Journal of the American Planning Association, 63(3), 329–344.

- Berke, P. R., Backhurst, M., Day, M., Ericksen, N., Laurian, L., Crawford, J., & Dixon, J. (2006). What makes plan implementation successful? An evaluation of local plans and implementation practices in New Zealand. Environment and Planning B, Planning & Design, 33, 581–600. https://doi.org/10.1068/b31166

- Berke, P. R., Godschalk, D. R., Kaiser, E. J., & Rodriguez, D. A. (2006). Urban Land Use Planning (5th ed.). University of Illinois Press.

- Berke, P., Kates, J., Malecha, M., Masterson, J., Shea, P., & Yu, S. (2021). Using a resilience scorecard to improve local planning for vulnerability to hazards and climate change: An application in two cities. Cities, 119, 103408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103408

- Berke, P., Masterson, J., Malecha, M., & Yu, S. (2020). Applying a plan integration for resilience scorecard to practice: Experiences of nashua. TX. Preliminary Report.

- Berke, P., Newman, G., Lee, J., Combs, T., Kolosna, C., & Salvesen, D. (2015). Evaluation of networks of plans and vulnerability to hazards and climate change: A resilience scorecard. Journal of the American Planning Association, 81(4), 287–302.

- Berke, P., Roenigk, D., Kaiser, E., & Burby, R. (1996). Enhancing plan quality: Evaluating the role of state planning mandates for natural hazard mitigation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 39(1), 79–96.

- Berke, P., Smith, G., & Lyles, W. (2012). Planning for resiliency: Evaluation of state hazard mitigation plans under the disaster mitigation act. Natural Hazards Review, 13(2), 139–150.

- Berke, P., Yu, S., Malecha, M., & Cooper, J. (2019). Plans that disrupt development: Equity policies and social vulnerability in six coastal cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 0739456X19861144.

- Bowyer, R. A. (1993). Capital improvement programs: Linking budgeting and planning. American Planning Association, Planning Advisory Service Report 442.

- Burby, R. J. (2006). Hurricane Katrina and the paradoxes of government disaster policy: Bringing about wise governmental decisions for hazardous areas. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 604(1), 171–191. Retrieved from. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25097787

- City of Rockport. (2006). A vision for Rockport: A master plan for the heritage district and downtown Rockport. Building and Development Department.

- City of Rockport. (2014). Rockport heritage district zoning overlay code. Building and Development Department.

- City of Rockport. (2017a). Aransas County multi-jurisdictional floodplain management plan. Building and Development Department. https://cityofrockport.com/655/Floodplain-Management-Plan

- City of Rockport. (2017b). Aransas County multi-jurisdictional hazard mitigation action plan. Building and Development Department. https://cityofrockport.com/670/Hazard-Mitigation-Action-Plan

- City of Rockport. (2018). Aransas County long term recovery plan. Building and Development Department.

- City of Rockport. 2020. Rockport Strong Comprehensive Plan 2020-2040. https://cityofrockport.com/ArchiveCenter/ViewFile/Item/2916

- Duerksen, C. J., Dale, C. G., & Elliott, D. L. (2009). The citizen’s guide to planning (4th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351179669

- Elmer, V., & Leigland, A. (2013). Infrastructure planning and finance (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA]. (2013). Integrating hazard mitigation into local planning: Case studies and tools for community officials. Retrieved from http://www.gema.ga.gov/Mitigation/Resource%20Document%20Library/Integrating%20Hazard%20Mitigation%20into%20Local%20Planning.pdf

- Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA]. (2015). Plan integration: Linking local planning efforts. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/media-librarydata/1440522008134ddb097cc285bf741986b48fdcef31c6e/R3_Plan_Integration_0812_508.pdf

- Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA]. (2022). National Flood Insurance Program Data. Open FEMA Data Sets. Retrieved August 26, 2022, from https://www.fema.gov/about/openfema/data-sets

- Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA]. (n.d.). Assistance for governments and private non-profits after a disaster. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.fema.gov/assistance/public

- Finn, D., Hopkins, L., & Wempe, M. (2007). The information system of plans approach: Using and making plans for landscape protection. Landscape and Urban Planning, 81(1–2), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2006.11.006

- Godschalk, D. R., & Anderson, W. R. (2012). Sustaining places: The role of the comprehensive plan. American Planning Association.

- Godschalk, D., Kaiser, E., & Berke, P. (1998). Integrating hazard mitigation and land use planning. In R. Burby (Ed.), Cooperating with nature: Confronting natural hazards with land use planning for sustainable communities (pp. 85–118). Joseph Henry Press.

- Godschalk, D. R., & Rouse, D. C. (2015). Sustaining places: Best practices for comprehensive plans (Vol. 578). American Planning Association.

- Hopkins, L. D., & Knaap, G. J. (2018). Autonomous planning: Using plans as signals. Planning Theory, 17(2), 274–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095216669868

- Lyles, W., Berke, P., & Smith, G. (2016). Local plan implementation: Assessing conformance and influence of local hazard plans in the United States. Environment and Planning B, 43(2), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813515604071

- Malecha, M., Berke, P., & Masterson, J. H. (2020). Plan integration for resilience scorecard for disaster recovery (PIRS-DR): Improving disaster recovery through spatial plan evaluation. In Application in Flood-Vulnerable Communities in the Texas Coastal Bend Region: Final Report. The Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi.

- Malecha, M., Masterson, J. H., Yu, S., & Berke, P. (2019). Plan integration for resilience scorecard™ guidebook: Spatially evaluating networks of plans to reduce hazard vulnerability – version 2.0. College Station. Institute for Sustainable Communities, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University. Retrieved from: http://mitigationguide.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Guidebook-2020.05-v5.pdf

- McDonald, L., Allen, W., Benedict, M., & O’Connor, K. (2005). Green infrastructure plan evaluation frameworks. Journal of Conservation Planning, 1(1), 12–43.

- National Research Council [NRC]. (2012). Disaster resilience: A national imperative. National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13457/disaster-resilience-a-national-imperative

- National Research Council [NRC]. (2014). Reducing coastal risk on the east and gulf coasts. National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18811/reducing-coastal-risk-on-the-east-and-gulf-coasts

- Nelson, A., & French, S. (2002). Plan quality and mitigating damage from natural disasters: A case study of the Northridge earthquake with planning policy considerations. Journal of the American Planning Association, 68(2), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360208976265

- NFHL, 2019. FEMA national flood hazard layer database. Retrieved from https://hazards-fema.maps.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=9c2a359ae6774070a8ba6460f2486068

- Norton, R. K. (2008). Using content analysis to evaluate local master plans and zoning codes. Land Use Policy, 25(3), 432–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.10.006

- Report, C. R. S., & Research Service, C. (2022). Introduction to the national flood insurance program (NFIP). https://sgp.fas.org/crs/homesec/R44593.pdf

- Rouse, D., & Piro, R. (2022). The comprehensive plan: Sustainable, resilient, and equitable communities for the 21st century. Routledge.

- Sullivan, E. J., & Lester, I. (2005). The role of the comprehensive plan in infrastructure financing. Urban Lawyer, 37(1), 53–86.

- Tomer, A., George, C., Kane, J., & Bourne, A. (2022, March 09). America has an infrastructure bill. What happens next? Brookings. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/11/09/america-has-an-infrastructure-bill-what-happens-next/

- United Nations General Assembly. (2015). United Nations world conference on disaster reduction – Sendai framework for disaster reduction 2015-2030. Retrieved from http://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). TIGER/Line shapefiles (machine-readable data files). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/time-series/geo/tiger-line-file.html

- Walters, E. (2018, August 24). No place back home: a year after Harvey, Rockport can’t house all its displaced residents. Texas Tribune. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.texastribune.org/2018/08/24/hurricane-harvey-year-later-rockport-cant-find-housing-evacuees/#:~:text=The%20tropical%20cyclone%20barreled%20ashore,of%20property%20damage%20in%20Texas.

- White House. (2021, August 01). Fact sheet: Historic bipartisan infrastructure deal. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/07/28/fact-sheet-historic-bipartisan-infrastructure-deal/

- Yu, S., Brand, A. D., & Berke, P. (2020). Making room for the river: Applying a plan integration for resilience scorecard to a network of plans in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(4), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1752776

- Yu, S., Malecha, M., & Berke, P. (2021). Examining factors influencing plan integration for community resilience in six US coastal cities using hierarchical linear modeling. Landscape and Urban Planning, 215, 104224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104224