ABSTRACT

Subjective interpretation of what is valuable to society is paramount for evaluating the merits of an intervention. As a result, social value (SV) evaluation go beyond objective evaluations. This evaluation is organic and has to do with the continuous challenges of being in the world with others, thus using different approaches to overcome social and environmental issues. Studies on SV overlooked how non-Western societies perceive SV in development projects. Hermeneutics is suitable to reveal SV’s social dimensions and explore individuals’ perceptions through their lived experiences beyond quantitative modelling. Therefore, this study applies a hermeneutical approach to SV to dissect the lived experiences of individuals working in national infrastructure planning in a non-Western society, which is Oman. The paper analyses 11 semi-structured interviews conducted with governmental decision-makers about Oman’s infrastructure development. Findings present a total of 14 outputs and 11 outcomes for developing an SV model mapped across different national infrastructure sectors. These sectors are energy, ICT, transport, waste, and water. Findings determine different sectors provide different forms of SV, with an energy sector project being the highest contributor of SV.

1. Introduction

The subjective interpretation of what is valuable to society is the central question in how a society evaluates the merits of an intervention (e.g., national infrastructure projects). Ultimately, social value (SV) and its evaluation fall beyond the confines of economic evaluation. Thus, SV advocates in the context of infrastructure planning and delivery need to understand why contemporary studies have failed to capture a unified meaning and criterion for defining and assessing SV for project stakeholders (Choi, Walters, Lam, et al., Citation2014; Doloi, Citation2018; Loosemore & Higgon, Citation2015; Mulholland, Chan, Canning, et al., Citation2020; Mulholland, Ejohwomu, & Chan, Citation2019; Raidén, Loosemore, Gorse, et al., Citation2019). While this interpretation of SV is not new, it correlates with the continuous challenges of being in the world with others, and thus having to use different approaches to resolve social issues.

Developed countries such as the UK and Australia have acknowledged the importance of national infrastructure in providing basic services for their societies to flourish. Social inequalities faced by indigenous communities are now addressed by Australia’s construction industry through social procurement policies such as the Commonwealth Indigenous Procurement Policy (Denny-Smith & Loosemore, Citation2017). Similarly, the UK’s (Public Services Social Value Act, Citation2012) was developed to ensure the nation’s private and public sectors provided additional benefits for communities impacted by their procurement activities. As a result, a substantial body of literature predominantly in the UK and Australia has focused on developing quantitative mechanisms, such as the social return on investment, for defining, evaluating, and measuring SV due to these mechanisms’ practicality in monetizing and reporting the SV of such projects (Denny-Smith, Sunindijo, Loosemore, et al., Citation2021; Mulholland, Ejohwomu, & Chan, Citation2019; Raidén, Loosemore, Gorse, et al., Citation2019).

However, there is a lack of diversity in SV research, and there is a need to address practices in other contexts, for instance, Arab-Muslim societies in non-Western countries. Such a lack can result in, as Malik (Citation2000) argues, ‘Western science and philosophy [establishing] a form of knowledge whereby non-Western societies and cultures are represented solely in terms of the categories of Western thought, and in which Western society acts as a standard against which all other societies are judged’.

To fill this gap, this study aims to develop an SV model for Oman’s national infrastructure to inform future planning on how to optimise the benefits by making the most of monetary sources. The study will outline how hermeneutics is used as an SV lens to elucidate and interpret the practices and traditions of an Islamic society and these traditions’ implicit commitment towards infrastructure development. The SV model presented in this study has been specifically developed for the Sultanate of Oman, a Muslim Arab country. The article seeks to answer how Omani decision-makers in Oman perceive and evaluate SV across five different infrastructure sectors: energy, information and communication technology (ICT), transport, waste, and water. To answer this question, 11 semi-structured interviews were conducted with different government representatives across the above-mentioned sectors who influence the planning and tendering process of national infrastructure projects in Oman.

2. Unlocking SV horizons in Oman: hermeneutics as a theoretical approach

Though hermeneutics may be an erroneous philosophical premise, human beings often live in a hermeneutic manner. The study of hermeneutics dates to before Christ, and the most notable philosophers of hermeneutics are Western. While hermeneutic pioneers such as Heidegger, Gadamer, and Habermas commend historicity and traditions to achieve valuable interpretation (Bernstein, Citation1982), little is known about the practices of other traditions, such as the experiences of Arab Muslim societies.

Kamali (Citation2003) identified ‘ta’wil’ and ‘tafsir’ as an Islamic practice for exegesis where the former describes the intellectual duty of the reader to disclose hidden meanings of the Quran’s text, while the latter is concerned with explaining and commenting on what the text is trying to speak about.

Ejohwomu and Igwilo (Citation2017) stated that a hermeneutical analysis realises that the text and its interpreter are a consequence of effective history. Thus, for the hermeneutic approach to establish what the text means, a dialogue in the form of questions and answers is needed to unlock the horizons of the text and fuse them with the interpreter’s knowledge horizon. These are tasks set by Islam when performing an exegesis, most notably for the Quran, to translate the lived experiences of the early Muslims into a ‘coherent system of thought, belief, jurisprudence and praxis’ (Freamon, Citation2006).

As highlighted by Ejohwomu and Igwilo (Citation2017), the co-existence of different cultures in a social space can either result in valuable social interaction or social status differentiation, for instance, between national communities and expatriates. Consequently, this paper asks the following question: How can an SV advocate identify what is valuable to Omani society? One method to understand the lived experiences of a society is through religion, which points to the different ways of identifying values agreed upon by a society.

Ives and Kidwell (Citation2019)) explained the impact of religion on SVs by explaining that the majority accept such horizons in lived experiences to ensure continuity in society. Accordingly, the SV of national infrastructure projects should reflect society’s horizons as a whole. Thus, it is paramount to dissect Omani’s lived experiences of SV. A number of SV outputs can be elicited from the Quran and Sunnah that reflect lived experiences that date back more than 1000 years.

The first SV output that can be amplified from an institution operating under Islamic law focuses on a continuous reassessment of Islamic jurisprudence. It strives to be innovative and critical of what is encouraged by the Quran and Sunnah, such as the consistency of social responsibility mandated by Sharia. This output is also called the ‘purposes of Sharia’, and it focuses on promoting well-being and human capital by educating individuals, eradicating poverty, and establishing justice to be compatible with socio-historical transitions (Aracil, Citation2019).

The second SV output is the ‘considerations of public interest’, which calls for innovative thinking in terms of economic, social, and political inquiries that emerged after the Islamic law (Taman, Citation2011). Kamali (Citation2003) indicated that this moral belief stimulated public hearings for resolving social, economic, and political issues through the consensus of an Islamic community on questions that the Quran and Sunnah did not address. Any change is considered beneficial only if it ensures the protection of individuals’ (1) lives, (2) lineage, (3) religion, (4) intellect, and (5) property (Taman, Citation2011). Oman’s responses to initiatives such as corporate social responsibility, free-trade agreements, foreign investment, sustainable development, in-country value (ICV) and so on are consistent with this concept of Islamic law and Muslims’ traditions as the responses acknowledge public interest as being significantly dynamic.

The third output is ‘Sadaqah’, a gesture that can take the form of monetary charity or socially responsible acts towards the community. Examples of practical acts include caring for orphans and the needy, conducting fair trade, fulfilling promises, ensuring free competition; and treating workers fairly (Taman, Citation2011). Presently, for tenders above three million Omani Riyals (7.8 million USD), Oman’s Tender Board encourages a 10% small and medium enterprises (SMEs) price preference, the use of 10% Omani material when available, and 30% Omanis representing the total contract workforce both in implementation and operation (Dawar, Citation2020).

Finally, the concept of ‘Baitul Mal’ (Exchequer or Public Treasury) seamlessly integrates social welfare as a basis for benefits provided to society. Taman (Citation2011) explains Baitul Mal as a compromise in which the state collects revenues to ensure the continual improvement of its citizens’ well-being. In current practice, the Omani government uses such revenue for social security, the procurement of public services, and projects, healthcare, education, and so on.

The discussion above entails that developing an SV model does not simply mean ‘transplanting’ what is found in a more advanced society but instead requires government decision-makers who are planning and developing Oman’s national infrastructure projects to explain why what they perceive as SV is aligned with the public interest. The first stage of developing the SV model for Oman’s national infrastructure is to discuss the literature on the subject matter.

3. Conceptualizing SV as a basis for developing an infrastructure delivery model

Infrastructure projects are required to fulfil developing countries’ aspiration for an enhanced quality of life. By 2050, it is expected that $90 trillion will be spent on infrastructure assets, whereas urban regions are expected to expand by three times (Bhattacharya, Oppenheim, & Stern, Citation2015). Moreover, the inclusion of SV requirements (i.e., outcomes) when planning national infrastructure projects is to ensure the provision of additional SV based on local needs. Benefits generated by infrastructure projects are not limited to providing basic services to a certain sector but also include advantages such as job creation and enhanced social wellbeing. Therefore, planning national infrastructure projects through a hermeneutic lens will potentially unlock a wider positive impact on societies, mainly due to the intensity of capital resources required for project delivery. Therefore, planning national infrastructure projects through a hermeneutic lens could have a much wider positive impact on societies because significant capital resources are required to deliver projects, and thus it is important to ensure that these projects will have significant SV.

Infrastructure planning uncertainty refers to the uncertainty surrounding whether the asset delivered will be beneficial over time. Thus, the asset’s time, cost, and quality success should not be considered independently from the long-term planned outcomes. Infrastructure planners should account for the present and forecasted volatility and changes. Planning is strategically important since it addresses stakeholders’ needs and the users’ expectations, which are important for the success of the project prior to implementation (Edkins et al., Citation2013). Due to their resource-intensive requirements, infrastructure projects have traditionally been built, owned, and operated by the public sector (Vuorinen & Martinsuo, Citation2019). This traditional approach to infrastructure provision has evolved over time to include partnering with the private sector (i.e., private-public partnerships). However, De Brujn and Dicke (Citation2006) argue that the private sector is driven by profit-based activities, and thus, such partnerships can create trade-offs that harm other public values.

There are several social, economic, and environmental challenges in Oman that infrastructure projects can aim to tackle. For example, in 2019, Oman had a youth unemployment rate of 13%, one of the highest in the Gulf Corporate Council (GCC). Moreover, Oman is among the highest contributors of CO2 emissions per capita in the Middle East and North Africa and relies heavily on foreign labour due to the low wages paid to foreign workers.

Certain legislation and policies in Oman have tried to address these challenges by fostering a larger domestic labour force, such as the ‘Omanisatoin’ policy, which was drafted to increase nationalisation of the labour force (Zerovec & Bontenbal, Citation2011). Ultimately, this policy aims to tackle Oman’s biggest social concern, mainly the high domestic unemployment rate and reliance on foreign labour.

Furthermore, Oman’s ICV program was initially adopted to tackle these social challenges in the country’s oil and gas sector. Petroleum Development Oman defines ICV as ‘the total spent retained in country that benefits business development, contributes to human capability development and stimulates productivity in Oman’s economy’. The purpose of ICV is to support Omanisation by developing the skills of the Omani national workforce. Additionally, the programme strives to increase the money spent on local goods and services.

Oman’s national development goals are also carried out through mid-term strategies known as 5-year development plans. In 2021, Oman initiated the first 5-year development plan to achieve ‘Oman 2040 Vision’. The vision incorporates 13 national priorities to ensure a society with creative individuals, a competitive economy, a sustainable environment, and improved governance. Such strategic visions set outcomes that are meant to improve societies’ socio-economic and environmental conditions (Oman 2040 Vision Document). Moreover, Oman is located on the south-eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia. With a total area of 309,000 km2, 82% of the land consists of sandy deserts, 15% of rocky mountains, and 3% of coastal areas; 30% of the total population lives in the capital and there is a natural urban-rural divide (Al Shueili, Citation2015). Al-Sabah (Citation2014) emphasised that such a divide can result in severe social implications, such as weaker social cohesion and a lack of infrastructure for basic services in rural areas.

Over the past decade, Oman and the rest of the GCC states have had a booming construction sector that ensures the area’s developmental needs and rapid urban growth are served (Ianchovichina et al., Citation2013). GCC states account for almost 80% of the Middle East and North Africa’s (MENA) infrastructure investment, with Oman being one of the top five countries in the region (Estache, Ianchovichina, Bacon, et al., Citation2013). The OECD (Citation2020) adds that GCC members must invest 5% of their GDP on infrastructure to address the existing infrastructure gaps in the country and limit the environmental and social costs of infrastructure projects.

3.1. Conceptual framework of the study and Oman’s SV model

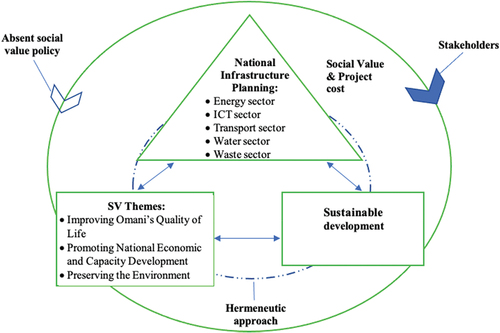

The review presented above indicates that Oman’s national infrastructure provision can unlock multiple forms of SV. Moreover, it can assist in achieving ‘Oman Vision 2040’. These forms of SV are the following: (1) Improving Omanis’ quality of life; (2) Promoting national economic and capacity development; (3) Preserving the environment. Another concept relevant to the reviewed literature is the concept of sustainability. Sustainability, although often used interchangeably with SV due to its similar dimensions, requires integral frameworks that embed social, economic, and environmental aspects to assess national infrastructure projects; these frameworks include the UN’s SDGs (see e.g., the United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP), Citation2020 assessment of SDG impacts). However, despite the value of using ‘externally defined goals’ for assessment, their impartial applicability to nations’ specific contexts make them less practical (Zuluaga, Karney, & Saxe, Citation2021). Hermeneutics is relevant in this case since the review indicates that an explicit SV policy (e.g., the UK’s policy) is not necessary to achieve benefits since infrastructure projects would provide change for society inevitably through.

Finally, the literature has thoroughly discussed stakeholders due to their influence on the outcomes of any infrastructure project. The reviewed literature has acknowledged the dynamism of SV and the importance of continuously engaging with stakeholders to maximise the delivery of SV (Daniel & Pasquire, Citation2019; Mulholland, Chan, Canning, et al., Citation2020; Mulholland, Ejohwomu, & Chan, Citation2019; Raidén, Loosemore, Gorse, et al., Citation2019; Watson, Evans, Karvonen, et al., Citation2016). , below, lists a number of the most advanced models and initiatives found in developed countries with respect to SV and infrastructure projects.

Table 1. Comparison of SV models and initiatives relevant to infrastructure planning.

below illustrates the conceptual framework explored in this study to group concepts that are broadly defined and systematically organised to provide a tool for the integration and interpretation of information that leads to new knowledge (McGregor, Citation2018). illustrates the first stage of the SV model, an outcome of the reviewed literature, for Oman’s national infrastructure by predicting and mapping a list of 11 outcomes across three identified themes when evaluating national infrastructure projects with respect to SV in Oman.

Table 2. Defined SV themes and outcomes specific to Oman’s development context.

4. Methodology

This study is part of an ongoing doctoral research study conducted between 2020 and 2022. The main study aims to develop a qualitative SV model for Oman’s national infrastructure to inform future planning on optimising the benefits of the money spent on such projects. Therefore, the main research study is based on an interpretive and socially constructed philosophical paradigm. As Guba and Lincoln (Citation1994) explain, this paradigm accepts reality as conceived by humans to be multiple, subjective, socially and experimentally constructed, and specific to the local context. Ultimately, this philosophical belief identifies research findings to be drawn co-constructively by the participants and researcher.

The data presented in this paper seeks to validate the defined SV themes and outcomes listed in in terms of Oman’s social context and the intended model. The next step entails testing the reliability of the model through a retrospective multiple case study strategy of at least two different sectorial projects to allow for cross-comparison (Mills et al., Citation2010; Rashid, Rashid, Warraich, et al., Citation2019; Ridder, Citation2017).

4.1. Sampling and recruitment

To obtain the data needed for answering the research question, the researcher must choose a suitable target with respect to the research subject matter (Islam, Citation2020). Therefore, the study investigated how government representatives working with Oman’s national infrastructure development perceive and assess SV. Interviews were conducted with government representatives, whether policy makers, regulators or implementers, who played a key role in the planning and delivery of publicly funded infrastructure projects across five infrastructure sectors: ICT, energy, transport, waste, and water. Non-probability sampling was chosen as this data collection phase aims to explore the meanings and perceptions of relevant experts in the field of Oman’s national infrastructure planning and how they perceive and assess SV with respect to national infrastructure projects.

Research participants were recruited by email through the researcher’s network. A key informant and gatekeeper with a senior position representing Oman’s Implementation Support and Follow-up Unit (ISFU) allowed the principal researcher to establish contact with relevant experts across Oman’s government entities. The ISFU’s main role is supporting and monitoring the implementation of government plans and programmes on national development and economic diversification. The study participants had to have at least 5 years of professional experience in Oman and the ability to give informed consent (granted permission from a higher authority). The choice of minimum years of experience is mainly because of Oman’s development plans, which are carried out at 5-year intervals. Thus, a total of 11 semi-structured interviews were conducted between October 2021 and January 2022. Six of the participants are political experts representing Oman’s Ministry of Energy and Minerals; Authority for Public Services Regulation; Ministry of Economy; Ministry of Transport, Communication, and Information Technology; and Oman Tender Board. The remaining five participants are considered to be technical experts and service providers representing Be’ah (the solid waste sector), Oman Water and Waste Water Company (the water and waste water sector), and Rakizza (the Infrastructure Investment Fund). below presents the case classification of research participants along with their roles and years of experience.

Table 3. Case classification of the 11 research participants.

4.2. Data collection method

Bogner, Littig, and Menz (Citation2018), and Döringer (Citation2021) explain that expert semi-structured interviews have significant value in socio-technical research as they are exploratory interviews. In addition, this interview method helps provide an initial understanding of a field that is new or poorly defined.

Bogner, Littig, and Menz (Citation2009) argue that experts can validate frameworks due to their specific knowledge gained from practice and experiences relating to a field of action and are thus able to provide meaning and guidance. This knowledge includes understanding how to be situated and integrated in various local contexts. Qualitative interviews with experts stress the significance of interpreting the experiences and perspectives of the interviewees to extend the understanding of social reality (Döringer, Citation2021).

According to Bogner, Littig, and Menz (Citation2009), qualitative interviews follow a topical guide and target the experts’ knowledge in a certain field. Bogner, Littig, and Menz (Citation2018) justified this due to the role and influence of experts becoming problematic in academic and civil societies. This is justified through the sociological debate on the rise of technical and political experts in modern society, whose intellect is science-based, could lead modern societies to come under expert dominance (i.e., become a technocracy) (Bogner, Littig, & Menz, Citation2009). A ‘technocracy’ is heavily relevant to a context where decision-making is centralised, such as in Oman. In these contexts, experts are chosen based on their technical, processual, and interpretive knowledge relevant to their area of expertise. In short, this paper has acquired knowledge that distinguishes experts in a specific field through semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions and by requesting relevant organisational documents.

5. Data analysis

The semi-structured interviews focused on the participants’ role in planning national infrastructure projects and their perception of the SV of such projects based on their experience following a well-defined interview protocol (Ang et al., Citation2016). Thematic analysis with the aid of NVIVO 12 was used to analyse the semi-structured interviews both inductively and deductively. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) best practices of thematic analysis were considered since their process initially starts with the researcher familiarising themselves with the data by reading the interview transcripts recurrently, identifying the initial research foci. Such an initial identification is also associated with deductive analysis since it should be restricted to the core elements of the entire research project (Neal et al., Citation2015). Fundamentally, the analysis process provided by Lindseth and Norberg (Citation2004) was adopted for interpreting the interviews.

Gadamer (Citation1989) explains that hermeneutics allows the researcher to have an enhanced understanding of ‘being-in-the world’ by understanding the ‘lived experience’ of those that researchers establish a dialogue with. In this regard, criticism of hermeneutics states that eliciting the subjective experiences and perceptions can be vulnerable to exploitation of data by principal researchers. Lindseth and Norberg (Citation2004) further explain that the principal researcher could naturally make judgments while interpreting a text. To overcome this issue, the researcher read the transcripts without matching the narrative of the research participants to the research question but rather through reflexive reading as recommended by Morgan (Citation2021). Thus, the first stage of data analysis started by conducting ‘naïve reading.’

Naïve reading is an inductive reasoning process (data-driven codes) for analysing and understanding participants’ experiences and perceptions, and the researcher should document any understandings they have about the subject matter before beginning the process (Lindseth & Norberg, Citation2004; Morgan, Citation2021). After naïve understanding is obtained, the next step is structural thematic analysis.

In the next step, meaning units (codes) were developed through line-by-line reading. Subsequently, codes were condensed into broader terms while still maintaining their original meaning, which was achieved by confirming whether the condensed meaning and themes correspond to the naïve understanding established in the first stage (Lindseth & Norberg, Citation2004). In cases where codes and themes did not match the understanding in the first stage, analysis commenced again from the naïve understanding until saturation was achieved. Moreover, thematic analysis delves deeper into text parts to convey a valuable meaning of what the participants are saying and considers the meaning units independent from the context of the text. This becomes key since hermeneutic studies goes beyond revealing repetitive patterns to portray the structure of meanings embodied in human experiences and perceptions (Laverty, Citation2003).

Once the condensed meaning of each code and theme resonates with the naïve understanding of each participant, themes were considered in relation to the research question. This stage of the thematic analysis is the ‘comprehensive understanding’ phase (Lindseth & Norberg, Citation2004). Additionally, relevant literature was used to further expand and explain the analysis of the interviews. In essence, this phase allows for understanding beyond what the interview transcripts say to what the text actually means. Gadamer identifies the iterative movement from the naïve understanding of all participants (whole) to a deeper understanding (each participants’ experiences/perception underpinned by context compared with the literature underpinned by theories and concepts) as the hermeneutic circle and states that the process is deductive in nature.

As a result of this analysis, the study identified four data analysis themes: (1) Oman’s national infrastructure definition, (2) Oman’s national infrastructure planning; (3) Oman’s social value definition, and, (4) Social value outputs of Oman’s infrastructure. The authors examined how the themes and outcomes of social value listed in are relevant. In this phase, the number of interviews was regarded as sufficient when data saturation was achieved – that is, when the analysis generated no new findings.

6. Results and discussion

6.1. Oman’s national infrastructure definition

Prior to data collection, the study adopted the definition given by Hall et al. (Citation2014), and Hall et al. (Citation2017), which suggested that national infrastructure assets are becoming more interdependent, working as a system within a national system that is governed by national policies and regulations.

The research identified five interconnected infrastructure sectors to investigate experts’ definitions of national infrastructure. One of the research foci of the expert interviewing process is to validate whether the adopted definition matches the definition provided by experts through the following question:

What does a national infrastructure project mean to you?

One of the experts explained that digital communication and information technology possess different infrastructure assets, such as telecommunication towers and data centres, but are heavily interdependent on one another. As a result, communication and information technology are under one policymaker – the relevant ministry – but with two undersecretaries, one for Transport and another for Communication and Information Technology.

In contrast, the Omani government has had a telecommunication regulatory authority, the TRA, solely for regulating telecommunications. This authority indicates there is an opportunity for improving Oman’s national IT sector by establishing a mandate for regulating IT in which the TRA will oversee the micro level of the national planning and the value of IT projects to ensure fair trade and protect the interests of Omani society. The significance of this regulatory gap in the IT sector is vital given there are IT based initiatives in Oman such as the Oman’s National Space and Artificial Intelligence Program.

below identifies nodes and codes taken from the interview transcripts, which are then used to construct each participant’s definition of the relevant national infrastructure sector.

Table 4. Condensed first tier codes of interview transcripts generated for the definition of national infrastructure.

6.2. Oman’s national infrastructure planning

The interview protocol included a probing question for the participants to explain the planning process relevant to their sector. Over 15 codes from each participant emerged by asking the following questions:

How are projects being planned in your organisation? Please share the type of documents associated with the planning stage and examples of the most valuable projects in your organisation.

Answers to these questions commonly identified the ‘Oman 2040 Vision Alignment’ as a constant factor that influences the planning process. Additionally, each entity is responsible for formulating their mid-term 5-year strategy, which should be aligned with the 10th five-year development plan, which stretches from 2021 to 2025. Moreover, the 10th development plan is considered to be the first step toward achieving Oman’s 2040 vision. Thus, participants were consistent in answering this question, in which common codes emerged that indicate the typical planning process that starts with developing a five-year strategy followed by an annual business plan that explains the needs identification, the change or addition of the service provided, that is, the change requirement, followed by concept design, project scope, and investment requirements.

The steps above (in italics) are made in-situ, meaning that each entity would be responsible for drafting their own strategies, which are bounded by their alignment to the 2040 vision and financial capacity. Once these steps are completed by the strategy/project planners, they are sent to the Ministry of Economy for project and budget approval before being sent, finally, to the Ministry of Finance. Moreover, experts provided examples of some of their most valuable projects in terms of scale, impact, and cost. The most valuable projects include ‘Ibri II 500 MW Solar PV Independent Solar Plant’, ‘Desalination Plant at Jalan Bani Bu Ali’, ‘Transforming Barka Dumpsite to Barka Engineered Landfill’, and ‘8-lane Al-Batinah Express Way’.

Another finding from this inquiry is that drastic changes have been made in Oman’s ministerial cabinet and governance since 2020. This includes the re-establishment of the Ministry of Economy. Due to its limited financial capacity, the ministry has established a matrix for prioritising development projects. The matrix is to be used in the future for project and budget approval for specific projects, and has the following purposes:

Utilising a methodology that can assist in classifying projects based on their priority with respect to Oman’s 2040 vision

Developing a standard set of criteria that can be used by civil ministries for developing their strategies and project pipelines

Having a methodology that is agile for choosing projects and that is dynamic and changeable when necessary

In addition, the matrix embeds two criteria for assessing the project’s social impact that have also been included in the developed social value framework of this study. These are the following:

Ensuring a clear and concise strategy for ICV, the number of people the project will serve, and the contribution of the project to enhancing the local economy and increasing social expenditures. A score of 5 (5 being the highest and 1 being the lowest) will be given for a project that contributes to serving a community of more than 500,000 people and a score of 1 for a project that serves a community of less than 50,000 people.

Employing Omani youth is at the forefront of the prioritisation matrix and is a core goal and outcome of the matrix in both the delivery and operation of the project. A score of 5 will be given for a project that provides more than 200 job opportunities and a score of 1 for projects that provide fewer than 50 job opportunities.

The matrix is exempt from being used for the following projects:

Projects assigned by a Royal Decree.

Maintenance projects.

Governorate development projects.

Projects financed either from loans or grants.

Projects that stimulate economic growth.

Projects that have been committed to by more than 40%.

After the Ministry of Economy approves of projects and the Ministry of Finance gives financial approval, requests for proposals made by each project owner will be circulated for tendering with the help of the tender board. State-owned companies such as Oman Water and Waste Water Company, Beah, and Oman Power and Water Procurement Company have their own independence in floating tenders and requesting proposals. Thus, Oman’s Tender Board is mainly responsible for tendering ICT and transport projects, and only one entity is responsible for strategy development, which is the Ministry of Transport, Communication, and Information Technology. Moreover, national infrastructure planning challenges emerged from the interview data, which denotes that the lack of data and information for project planning is a fundamental challenge for national infrastructure planning. To tackle this shortcoming, the Ministry of Economy is currently working on establishing a project management office as some ministries lack the capacity to manage projects. One of the Ministry of Economy representatives explained the following:

Currently, the government is planning to establish what they call a PMO, which is meant for project management. It will actually take care of all projects from A to Z. We have realised that for some ministries, [project management] is not their core business. (Participant 4)

A representative from the tender board indicated that there is an ongoing challenge in achieving the Omanization target, which is 30% of the project contract, in addition to including 10% price preference for SMEs and procuring local products:

If we bring all that we have developed over the years internationally, it will be difficult to implement it in Oman because we have limited resources, I mean in the project development (lack of capacity), and when I say project development, I mean from the planning to completion. So, this is one of the challenges we are facing: we have just three elements: Omanization, local products, and SMEs, and there are difficulties in implementing them in Oman. (Participant 8)

Another significant finding of the interview process is the influence of international agendas such as the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in which participants were asked:

How do international agendas influence decisions made at the planning stage of your organization’s projects? For example, the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals.

Participants indicated that Oman has integrated the 17 SDGs into the 2040 vision. They explained that the core pillars of the long-term plan embed the UN’s SDGs. However, while the vision incorporates international agendas at a national level, these agendas will also be reflected in the projects intended to achieve the vision’s goal. Participants 4 provides the following example on the influence of international agendas:

It is not really influencing but rather [it is] something that we consider, meaning we do not get any influence from this organisation because we are not getting any sort of financial [support] or loans from these organisations so they don’t have the influence on our national decisions. Instead, we benefit from their experiences and we watch out what is going on in the world and plan accordingly. (Participant 4)

Finally, participants were asked the following question:

Who are the key stakeholders and decision-makers in your organization’s projects?

Participants indicated that the Ministry of Economy and the Ministry of Finance are the two key and constant stakeholders when planning their organization’s projects. In addition, each sector (except for transport and the ICT sector) is divided into policymakers, regulators, operators, and implementers. Typically, the ministry representing each infrastructure sector is considered to be the policymaker. Implementers and operators are responsible for delivering and operating infrastructure projects at a micro-level and addressing challenges faced by end users to report them to policymakers and regulators.

6.3. Definition of social value in Oman

The developed definition is based on the literature reviewed on the different SV definitions and follows the UK’s Social Enterprise definition since this definition has an associated cost element:

SV determines how limited public resources are allocated and used to provide more value for money, meaning that if X amount of money is spent on the delivery of projects, that same amount of money could also produce a wider social, economic, and environmental positive impact to the community.

Cost-Effective: ‘but in general we are trying to reach or to provide a service for all the people with an economic cost for sure’. (Participant 5)

What we are trying to do is basically to strike a balance between the economic and social perspectives of the project. (Participant 4)

Policy Social Implication: ‘[SV is the] social impact of each (energy) policy on the public and economic sectors’. (Participant 1)

Direct-Indirect Value: ‘SV is the impact of the project, it is the direct or indirect impact of the project on the community … For example, the direct impact is the cost of electricity … The indirect impact occurs if we increase the electricity tariff for the commercial or industrial sector, which will increase the price of goods and services they provide’. (Participant 1)

Multi-Dimensional Value: ‘[SV aims] to improve the quality of electricity and have a performance improvement for the companies that will reflect on the quality of life of the customer’. (Participant 2)

Community Driven: ‘…the increase of requests and the pressure we receive from the public to further expand the networks, unless there is a great value they perceive or they see, they would not pressure us to continually expand’. (Participant 5)

Contextually driven: ‘It depends on the nature of the project and the outcome. The weighting will be different depending on how the project manager evaluates it’. (Participant 9)

Investment-Based:” So when we talk about the investment, we are aiming to improve the quality of electricity”. (Participant 2)

Non-uniform: ‘So citizens, overall, have to feel this developmental process because we are trying to avoid an economic growth that is not reflected in the citizen’s eye’. (Participant 6)

6.4. Social value outputs of Oman’s infrastructure

The final phase of the interview protocol focused on obtaining a definition of what SV means to different experts in Oman’s infrastructure planning, which has been discussed in Section 4.3. Moreover, participants were then asked probing questions on how they would assess SV:

Describe how you perceive what is valuable to others.

All participants repeated a number of SV outputs such as Omanisation, Inclusion of SMEs, Reducing pollutants emitted into the local environment. Energy experts were the only ones to identify an exclusive sector-specific output, namely to promote green molecules’ production:

If we talk about every solar plant, for example, now that this project is complete, Oman can sell the green molecules. Which means there are a number of industries around the world that are looking for green molecules-type products. For example, if you are making plastics, some countries will make some mandatory requirements that I will only buy from you if the plastic is produced from clean energy. So in addition to the main objective of reducing the cost of energy, one of the bi-products … that the local companies in Oman can claim/buy some green molecules from this plant to show that they can sell their products as clean products. So I think this is additional value from every solar project. Participant 2)

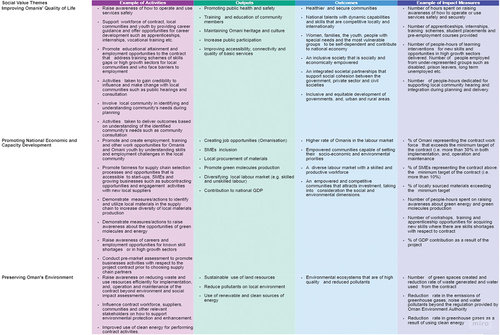

Having analysed and discussed the results of the expert interviews, blow showcases the outputs and outcomes of the framework based on the data analysis of the 11 semi-structured interviews that can be used to predict how SV can be assessed at a project level for 5 infrastructure sectors. presents the achievable outputs with respect to each infrastructure sector. It is important to note that while the ‘outputs’ and ‘outcomes’ are validated for Oman’s context, ‘Example of Activities’ and ‘Example of Impact Measures’ have been developed by using the practices of the UK’s SV assessment (Government Commercial Function, Citation2020a).

Figure 2. Social value assessment model for Oman’s national infrastructure sectors. Figure developed using www.miro.com.

Table 5. Validated social value themes, outputs and outcomes for Oman’s infrastructure projects.

7. Conclusion

The main objective of this paper is to present an SV model to inform national infrastructure planners in Oman on how to assess the SV of different sectorial infrastructure projects by utilising a hermeneutical theoretical approach. This paper presents findings from the data analysis, which allowed the researchers to refine the content of the SV themes and criteria based on the interviewing process.

A review of the literature provided the study with best practices for activities and measures to identify the impact of SV thinking in Oman’s infrastructure planning. The retrospective multiple case study is crucial to assist the researcher in evaluating past infrastructure projects in Oman and identifying the resources required (inputs) for conducting the tasks (activities) and the impact measures of achieving the outputs and outcomes presented in this report.

The first stage of data collection explored the definitions of SV and national infrastructure, the planning process of national infrastructure projects, and the assessment of SV in Oman. The data analysis identified an output for the SV for each of the criteria (outcome). Different constructs of the model were noted by looking at different assessment models of SV. First, the model is intended to inform how SV can be fostered in different contexts, specifically for planning infrastructure sectorial projects in Oman. Second, the model can be used by national infrastructure planners, ministries, and entities with a project pipeline and by national tenders’ evaluators in Oman to highlight areas in which there can be value optimization for communities through publicly funded projects.

Using this model can potentially increase the maturity of Oman’s national infrastructure delivery in terms of how different models can be developed to provide additional value for society. However, the model is limited to collecting citizens’ perceptions of national infrastructure and the value of this infrastructure.

Regardless of the several quantification methods available for monetizing SV, findings indicate that strategy formulation can ensure a valuable change in a context such as Oman where there is a gap in monetizing SV. In Oman’s case, assessing value starts with identifying the intended outcomes of an intervention to indicate the long-term benefit/impact that an intervention seeks to achieve. As a result, outputs will be developed to clarify what a project activity aims to achieve (Parsons, Gokey, & Thornton, Citation2013). Consequently, the inputs (resources) needed to achieve the activity can then be perceived as outputs and intended outcomes. Finally, impact measures are set (whether qualitative or quantitative) to provide a mechanism for reflecting relevant changes beyond the planned for change.

Returning to model validation in this study, it is evident that the SV outcomes of the various national infrastructure projects in Oman are similar. Thus, national infrastructure projects should be able to achieve equality in terms of different governorate development; thus, an outcome of infrastructure planning and development of the country for the next two decades which is an outcome of infrastructure planning and development for at least the next two decades as outlined in the Oman Vision 2040.

The development and validation of the model through expert interviews and the literature assisted in answering the research question. The study identified SV outputs and outcomes based on participants’ lived experiences and knowledge horizons. However, the inputs needed for conducting activities to achieve the outputs and outcomes (i.e., resources needed to conduct activities for achieving the outputs) are still unknown. Equally important, data is needed to understand the impact measures of the above-mentioned variables.

Ethics approval for data collection

Prior to data collection, the principal investigator has applied an ethics application to the ‘Research, Ethics and Integrity’ department at the University of Manchester. The reference number of the application is: 2021–12692–20653.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Mahmood Zahir Al-Hinai

Ahmed Mahmood Zahir Al-Hinai is a PhD Researcher at the at the University of Manchester. His research project titled ‘A Hermeneutical Approach to Social Value: A Case Study of National Infrastructure Planning in Oman’ investigates the impact of social value thinking on national infrastructure planning in Oman by creating a social value model for Oman’sl infrastructure.

Obuks Ejohwomu

Dr Obuks Ejohwomu is a Reader in Sustainable Built Environment and Project Management at The University of Manchester. He leads a research group focusing on a future sustainable built environment. Associate Editor for Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology.

Mohamed Abadi

Dr Mohamed Abadi is a lecturer in the ‘Management of Projects’ in the Department of Engineering Management, University of Manchester. He has conducted research and authored/co-authored several publications about sustainability, circular economy, social value, and digital transformations in construction.

References

- Al-Sabah, M. (2014). Intangible infrastructure of the GCC: Bridging the divide. Global Society, 28(2), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2014.887554

- Al Shueili, K. (2015). Towards A Sustainable Urban Future in Oman: Problem and Process Analysis (Muscat as A Case Study) [ Doctoral Dissertation]. Retrieved from The Glasgow School of Art.

- Aracil, E. (2019). Corporate social responsibility of islamic and conventional banks. IJOEM, 14(4), 582–600. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2017-0533

- Bernstein, R. J. (1982). From hermeneutics to praxis. Review of metaphysics. The Review of Metaphysics, 35(4), 823–845.

- Bhattacharya, A., Oppenheim, J., & Stern, N. (2015). Driving sustainable development through better infrastructure: Key elements of a transformation program. Working Paper 91. Global Economy and Development,

- Bogner, A., Littig, B., & Menz, W. (2009). Interviewing experts. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bogner, A., Littig, B., & Menz, W. (2018). Generating qualitative data with experts and elites. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection (pp. 652–665). SAGE Publications Ltd. 10.4135/9781526416070

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bruijn De, H., & Dicke, W. (2006). Strategies for safeguarding public values in liberalized utility sectors. Public administration, 84(3), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00609.x

- Carpenter, B., & Mizia, A. (2018). Exploring the alignment of the social value principles and the national TOMs framework developed by the social value portal. Social Value UK and The Social Value Portal.

- Cheng, A. K., Sankaran, S., & Patricia, K. C. (2016). ‘Value for whom, by whom’: Investigating value constructs in non-profit project portfolios. PMRP, 3, 5038. https://doi.org/10.5130/pmrp.v3i0.5038

- Choi, Y., Walters, A. T., Lam, B., Green, S., Na, J. H., Grenzhaeuser, S., & Kang, Y. (2014). Measuring social values of design in the commercial sector. Final Report. Brunel University London and Cardiff Metropolitan University

- Daniel, E., & Pasquire, C. (2019). Creating social value within the delivery of construction projects: The role of lean approach. Engineering, Construction & Architectural Management, 26(6), 1105–1128. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-06-2017-0096

- Dawar, K., (2020). Public procurement and manufacturing diversification in Oman. Final Report. Univeristy of Sussex. School of Law.

- Denny-Smith, G. and Loosemore, M. (2017). ”Integrating Indigenous enterprises into the Australian construction industry” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 24(5), 788–808. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-01-2016-0001

- Denny-Smith, G., Sunindijo, R. Y., Loosemore, M., Williams, M., & Piggott, L. (2021). How construction employment can create social value and assist recovery from COVID-19. Sustainability, 13(2), 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020988

- Doloi, H. (2018). Community-Centric Model for Evaluating Social Value in Projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 144(5). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001473

- Döringer, S. (2021). ‘The problem-centred expert interview’. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1766777

- Edkins, A., Geraldi, J., Morris, P., & Smith, A. (2013). Exploring the front-end of project management. Engineering Project Organization Journal, 3(2), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/21573727.2013.775942

- Ejohwomu, O., & Igwilo, M., (2017), A hermeneutical analysis of brutalism, equlity and diversity in innovative construction. in P. Chan (Ed.), The Association of Researchers in Construction Management: Procs 33rd Annual ARCOM Conference, Cambridge, UK, 4-6 September. 2017, Cambridge, UK, Association of Researchers in Construction Management.

- Estache, A., Ianchovichina, E., Bacon, R., & Salmon, I. (2013). Infrastructure and employment creation in the Middle East and North Africa. World Bank.

- Freamon, B. K., (2006). Some reflection on post-enlightenment qur’anic hermeneutics. Michigan State Law Review. Seton Hall Public Law Research Paper No. 1107032.

- Gadamer, H. G. (1989). Truth and method (Weinsheimer, J., Marshall, D.G. Trans., 2nd ed.). Continuum.

- Government Commercial Function. (2020a). Guide to using the social value model. UKGov.

- Government Commercial Function. (2020b). The social value model. UKGov.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage.

- Hall, J. W., Henriques, J. J., Hickford, A. J., Nicholls, R. J., Baruah, P., Birkin, M., Chaudry, M., Curtis, T. P., Eyre, N., Jones, C., & Kilsby, C. G. (2014). Assessing the long-term performance of cross-sectoral strategies for national infrastructure. Journal of Infrastructure Systems, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943–555X.0000196

- Hall, J. W., Thacker, S., Ives, M. C., Cao, Y., Chaudry, M., Blainey, S. P., & Oughton, E. J. (2017). Strategic analysis of the future of national infrastructure. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Civil Engineering, 170(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1680/jcien.16.00018

- Ianchovichina, E., Estache, A., Foucart, R., Garsous, G., & Yepes, T. (2013). Job creation through infrastructure investment in the Middle East and North Africa. World Development, 45, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.11.014

- Islam, M. (2020). Data analysis: Types, process, methods, techniques and tools. IJDST, 6(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijdst.20200601.12

- Ives, C. D., & Kidwell, J. (2019). Religion and social values for sustainability. Sustainability Science, 14(5), 1355–1362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00657-0

- Kamali, M. H. (2003). Principles of Islamic jurisprudence. Islamic Texts Society.

- Laverty, S. (2003). Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: A comparison of historical and methodological considerations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(3), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690300200303

- Lindseth, A., & Norberg, A. (2004). A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 18(2), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00258.x

- Loosemore, M., & Higgon, D. (2015). Social Enterprise in the construction industry: Building better communities (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Malik, K. (2000). Universalism and difference in discourses of race. Review of International Studies, 26(5), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210500001558

- McGregor, S. (2018). Conceptual and theoretical papers. In Understanding and evaluating research (pp. 497–528). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (Eds.). (2010). Encyclopedia of case study research. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412957397

- Morgan, D. A. (2021). Analysing complexity: Developing a modified phenomenological hermeneutical method of data analysis for multiple contexts. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 655–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1847996

- Mulholland, C., Chan, P., Canning, K., & Ejohwomu, O. (2020). Social value for whom, by whom and when? Managing stakeholder dynamics in a UK megaproject. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Management, Procurement and Law, 173(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1680/jmapl.19.00018

- Mulholland, C., Ejohwomu, O., & Chan, P. W. (2019). Spatial-temporal dynamics of social value: Lessons learnt from two UK nuclear decommissioning case studies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117677

- Neal, J. W., Neal, Z. P., VanDyke, E., & Kornbluh, M. (2015). Expediting the analysis of qualitative data in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 36(1), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214014536601

- OECD, (2020). Investment in the MENA Region in the Time of COVID-19. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.oecd.org/.

- Okpala, A. N., & Yorkor, B. (2013). A Review of modeling as a tool for environmental impact assessment. International Research Journal in Engineering Science and Technology, 10(1).

- Parsons, J., Gokey, C., & Thornton, M. (2013). Assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. Retrieved February 17, 2022, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/304626/Indicators.pdf

- Public Services (Social Value) Act. 2012. Chapter 3. Her Majesty’sStationery Office,

- Raidén, A., Loosemore, M., Gorse, C., & King, A. (2019). Social Value In Construction (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Rashid, Y., Rashid, A., Warraich, M. A., Sabir, S. S., & Waseem, A. (2019, January). Case study method: A step-by-step guide for business researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 160940691986242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919862424

- Ridder, H. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Bus Res, 10(2), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-017-0045-z

- Taman, S. (2011). The concept of corporate social responsibility in Islamic Law. Indiana International & Comparative Law Review, 21(3), 481–508. https://doi.org/10.18060/17662

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (2020) . SDG Impact Standards. SDG Impact UNDP.

- Vuorinen, L., & Martinsuo, M. (2019). Value-oriented stakeholder influence on infrastructure projects. International Journal of Project Management, 37(5), 750–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.10.003

- Watson, K., Evans, J., Karvonen, A., & Whitley, T. (2016). Capturing the social value of buildings: The promise of social return on investment (SROI). Building and Environment, 103, 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.04.007

- Zerovec, M., & Bontenbal, M. (2011). Labor Nationalization Policies in Oman: Implications for Omani and Migrant Women Workers. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 20(3–4), 365–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719681102000306

- Zuluaga, S., Karney, B., & Saxe, S. (2021). The concept of value in sustainable infrastructure systems: a literature review. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 1(2), 022001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/ac0f32