ABSTRACT

This study examines the transplantation of clusters through ‘follow sourcing’ of Korean electronics industry transnational corporations (TNCs), their suppliers and individual actors in northern Vietnam, and the ways in which geographical and organizational proximity generate spillovers to local enterprises. Advanced manufacturing facilities, relationships with suppliers and training programmes give rise to direct and indirect learning and improvements in skills and technological capabilities. Transplanted clusters via follow sourcing and localization can serve as an intermediate stage between an externally controlled satellite cluster and an advanced cluster and they afford another latecomer development path to the Chinese model of ‘obligated embeddedness’.

摘要

越南北部韩国电子公司的’跟随采购’和其转移和本土化。Area Development and Policy. 本文通过’跟随采购’韩国电子产业跨国公司 (TNC) 和其供应商, 以及位于越南北部的个体参与者, 探讨了集群转移、以及地理和组织邻近性对当地企业产生溢出效应的方式。研究表明, 先进的生产设施、与供应商的关系和培训计划有利于直接和间接学习和在技术和技术能力上的改进。通过’跟踪采购’和本土化转移集群可以被作为外控卫星集群和先进集群之间的中间阶段, 并为中国’义务嵌入’模式提供了另外一条发展道路。

RESUMEN

‘Follow sourcing’ y la reubicación y localización de empresas electrónicas coreanas al norte de Vietnam. Area Development and Policy. En este estudio se analizan las reubicaciones de aglomeraciones a través de la estrategia ‘follow sourcing’ (seguir el abastecimiento) de las corporaciones transnacionales (CTN) de la industria de la electrónica coreana, sus suministradores y protagonistas individuales en el norte de Vietnam, y el modo en que la proximidad geográfica y organizativa puede generar efectos secundarios en las empresas locales. Las plantas de producción avanzadas, las relaciones con los proveedores y los programas de formación generan un aprendizaje directo e indirecto y mejoras en las habilidades y capacidades tecnológicas. Las aglomeraciones reubicadas mediante la estrategia de seguir el abastecimiento y la localización pueden servir de fase intermedia entre una aglomeración satélite controlada externamente y una aglomeración avanzada, y proporcionan otra ruta de desarrollo tardío al modelo chino de ‘incorporación obligada’.

Аннотация

‘Последующий поиск поставщиков’ и трансплантация и локализация корейских электронных корпораций в северном Вьетнаме. Area Development and Policy. В этом исследовании рассматривается трансплантация кластеров посредством ‘последующего поиска’ поставщиков и контрагентов в северном Вьетнаме транснациональными корпорациями корейской электронной промышленности (ТНК), а также способы, с помощью которых географическая и организационная близость создает побочные эффекты для местных предприятий. Современные производственные мощности, отношения с поставщиками и учебные программы способствуют прямому и косвенному обучению и совершенствованию навыков и технологических возможностей. Пересаженные кластеры с помощью последующего поиска и локализации могут служить промежуточным этапом между кластером спутников, управляемым извне, и передовым кластером и обеспечивают еще один путь позднего развития китайской модели ‘обязательной интеграции’.

INTRODUCTION

Foreign direct investment (FDI) plays an important role in corporate strategies and the development of host and parent regions including in South and East Asia where Gereffi (Citation1999) and other scholars (Lyberaki, Citation2011; Thomsen, Citation2007) have described the geographical expansion and industrial upgrading in newly industrializing economies (NIEs) as the process of ‘triangle manufacturing’. East Asian contractors in South Korea (Korea hereafter), Japan, and China who export to the European Union (EU) or United States often have subcontracts in Vietnam (Thomsen, Citation2007), and also participate in triangular manufacturing activities. The upgrading of Korean electronics companies has seen their transformation from subcontractors and original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to global high-technology market leaders. These companies have established branch production units in China, Southeast Asia and other continents, and then evolved into transnational corporations (TNCs) with several overseas production subsidiaries and research and development (R&D) facilities (Kim, Citation2020; Koo, Citation2017). Since 2010 Vietnamese companies became important manufacturing partners for Korean electronics firms. This development reflects the prominent role of global production networks (GPNs) with increased ‘trade in tasks’ or intermediate goods (MacKinnon & Cumbers, Citation2019; Yeung & Coe, Citation2015).

An important question concerns the extent to which host regions with limited technological and financial capacities and weak political power can participate in GPNs and establish clusters that contribute to latecomer development. In the light of this question this study analyses the transplantation of electronics clusters to Vietnam through Korean TNCs’ follow sourcing, as well as the localization process incorporating spillovers, suppliers and individual actors. The results help identify a developmental model for latecomer countries.

Data collection involved open-ended and semi-structured face-to-face interviews with chief executive officers (CEOs), managers and employees (past and present) of TNC subsidiaries, suppliers and related organizations, drawing on the demonstrated effectiveness of these methods in international business research in Asia (Kleibert, Citation2016; Yeung, Citation1995). The field research involved 29 interviews and was conducted in Vietnam from October 2014 to July 2018 (see Appendix A in the supplemental data online). This research was supplemented by analyses of secondary materials such as company reports, newspaper articles and statistical data.

This rest of this paper is structured as follows. After examining literatures on FDI and construction by suppliers of clusters in the host region, the third section explains the rising economic interdependence between Korea and Vietnam. The fourth and fifth sections examine Korean TNCs’ transplantation of satellite hub-and-spoke clusters in northern Vietnam, particularly focusing on the follow electronics sourcing, as well as the localization processes of local governments, TNCs, their suppliers, local firms and individual actors. The sixth section identifies the characteristics of an Asian South–South FDI model which differs from China-related models.

LITERATURE REVIEW

TNCs’ foreign investment and their suppliers: follow sourcing

‘Variegated capitalism’ (Peck & Theodore, Citation2007) is associated with a diversification of FDI models from traditional North–North and North–South to emerging South–South. Chandra et al. (Citation2013) emphasized the South–South FDI as drivers of industrialization for low-income host countries because they can follow the growth trajectory of leading developing countries like Korea and China from labour- to capital- or technology-intensive sectors. Developing country TNCs also have a relative advantage caused by their previous experience of similar inferior business environment when investing in other developing or the least developed countries in the South–South FDI context (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, Citation2008; Lipsey & Sjohölm, Citation2011).

TNCs, especially in the electronics and automobiles sectors, often establish producer-driven value chains by investing in overseas branch plants and subsidiaries, along with their suppliers and customers. Korean TNCs prefer greenfield investments. Suppliers and subcontractors are required to follow customers, in accordance with a ‘customer-following overseas expansion’ aspect of supply chain management (Kim, Citation2020). TNCs’ follow sourcing involves geographical proximity of production links, and organizational proximity of existing buyers and suppliers.

Geographical proximity leads to cost reduction in logistics and communications with positive effects on industrial agglomeration, triggering subsequent investment in the same and related industries. Proximity promotes subcontract relationships, thus enhancing supply-chain flexibility and supply-time reduction (Holl et al., Citation2010). The electronics industry, a representative modular production sector, can thus produce and sell finished products by assembling parts produced individually. Geographical proximity is also important in overcoming logistical constraints affecting the relationships between suppliers and final assemblies (Frigant & Lung, Citation2002) and can contribute to technology transfer (Ivarsson & Alvstam, Citation2005).

Organizational proximity (Boschma, Citation2005) is often associated with former affiliation and collaboration experiences (Park & Koo, Citation2021), with buyer–supplier relationships, joint venture arrangements, collaboration in marketing or R&D, and various informal networks. Previous long-term supplier relationships enable TNC assembly branches to reduce uncertainty based on reputation and trust.

Transplantation of satellite hub-and-spoke clusters in host economies

Markusen (Citation1996) identified four cluster types: the Marshallian, hub-and-spoke, satellite platform and state anchored. In hub-and-spoke clusters, a single or small group of large firms usually builds buyer–supplier linkages with local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The lead firm is the anchor, and a hub can be a supplier or buyer. Satellite clusters chiefly comprise branch plants – externally owned production units with strong nonlocal supplier or buyer linkages. In a typical hub-and-spoke model, the hub is a large locally headquartered company acting as an anchor in local economies. However, hub firms assume different forms such as joint ventures or externally controlled branches in evolving and diversified clusters. Florida and Kenney (Citation1991) defined ‘transplants’ as firms that are wholly externally owned or have a significant external participation in cross-national joint ventures, and called the cluster of transplant assemblers and suppliers a ‘transplant corridor’. Newly emerging economies and developing countries generally adopted a selective FDI promotion route in designated host regions serving as satellite platform clusters. However, if TNCs want to locate their supply chains near satellite facilities, they create an industrial complex with hub-and-spoke production relationships. Therefore, hub-and-spoke clusters focus on production linkages between customers and suppliers within a local cluster, while satellite clusters focus on organized production linkages of externally controlled companies with a nonlocal cluster.

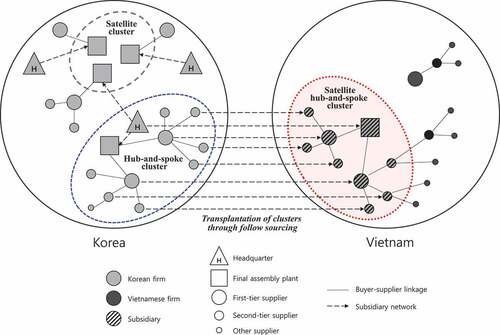

Externally controlled large assembly firms and their subcontractors connected in hub-and-spoke production linkages can agglomerate in satellite export platforms. We call this a ‘satellite hub-and-spoke cluster’ (). TNCs transplant ‘satellite hub-and-spoke clusters’ into host regions comprising satellite-type hub buyers and satellite-type spoke suppliers. Such transplanted clusters are different from advanced satellite or advanced hub-and-spoke clusters (Markusen & Park, Citation1995). Advanced types have evolved from original satellite and hub-and-spoke clusters by developing local networks and increasing the degree of embeddedness. Park (Citation1996) emphasized that these types have evolved with spin-offs and start-ups through local entrepreneurship, thereby creating links with local SMEs. Advanced hub-and-spoke clusters evolve with improved subcontracting and inter-firm relations, new start-ups, and spin-offs within clusters. If technological spillovers and new firm creation (new spin-offs and start-ups) occurs in local networks, original production satellite clusters can evolve into advanced satellite clusters. However, in cases such as Vietnamese manufacturing clusters foreign companies’ local networks with host economies’ firms have not yet developed as it is difficult for local companies to meet global TNC standards, especially in underdeveloped countries with limited regional technological assets and human resources. Hub-and-spoke linkages initially transplanted into host clusters in developing countries through follow sourcing can however help local firms engage participate in global production linkages and can thus be an intermediate stage between an externally controlled satellite cluster and advanced clusters.

Localization efforts and the role of individual actors

Host economies can experience direct positive employment, trade, capital and tax revenues effects as a result of TNCs’ FDI, with potential indirect effects on the development of skills and technologies, management skills, entrepreneurship and the industrial environment. Buyer–supplier linkages between foreign and domestic firms and spillovers (copying foreign firm’s products, imitating their skills and techniques, or learning business and workforce management methods) from TNCs (Lipsey & Sjohölm, Citation2011) can increase regional competitiveness. Spillovers from foreign firms can assume two forms: horizontal and vertical (Pavlínek & Žížalová, Citation2016). Horizontal spillovers are unintentional and indirect effects not associated with direct backward or forward linkages in the same industry including competitors. Vertical spillovers are intentional and/or unintentional effects associated with direct backward and forward buyer–supplier linkages, usually observed between TNC subsidiaries and domestic firms. Therefore, building production linkages with TNCs is an important opportunity for both local firms and regions. Ivarsson and Alvstam (Citation2005) explained that backward linkages are an important channel of technology transfer from foreign-invested assemblers to local suppliers. Such vertical production linkages are important because they allow information exchange, learning about products and technical processes, and accumulation of knowledge about business partners and institutional factors.

However, in latecomer developing countries, spontaneous technology, skill and intangible know-how spillovers associated with increased integration and embeddedness in TNCs’ global value chains (GVCs) and networks are difficult to realize (Mackinnon, Citation2012; Wrana & Nguyen, Citation2019). Hess (Citation2004) identified three forms of embeddedness: societal, network and territorial. Territorial embeddedness refers to the anchoring of production networks in different places, or the efforts to fix investment in a particular location and the resulting economic benefits and spin-offs (MacKinnon & Cumbers, Citation2019). Liu and Dicken (Citation2006) distinguished between active and obligated forms of embeddedness. In the former a TNC tries to find assets widely available in different locations and incorporate them actively and voluntarily. ‘Obligated embeddedness’ occurs where assets that are highly important for a TNC are not freely available or are controlled by the state, and a state bargaining power increases as in the case of China where the state used integration with GPNs to boost domestic industries (Gao et al., Citation2019). TNCs’ desire to access both fast-growing Chinese markets and low-cost production sites strengthened state bargaining power with an obligation to enter joint ventures, transfer technology, and localize production (Schwabe, Citation2020). However, other developing countries in much weaker positions often struggle to localize and embed the production linkages and knowledge networks of foreign in domestic territorial clusters.

Meanwhile, individual actors play a major role in localization efforts, especially as knowledge transferrers. Ettlinger (Citation2003) argued that individual actors are important units of analysis, and trust should be viewed as an interpersonal relationship, not just as a corporate or organizational relationship (Koo & Park, Citation2012). Expatriates from TNC headquarters are important actors in business and knowledge networks over distances that build upon temporary face-to-face interactions (Bathelt & Henn, Citation2014). TNCs quasi-permanently assign expatriate managers and technology experts to new locations and rotate other personnel to establish and control knowledge flows (Millar & Salt, Citation2008). Firms use expatriate staff to ensure corporate business objectives are met, provide managerial and technical expertise for long-term development, enhance the international careers of the firm’s cadres, and allow the firm time to identify and recruit local staff (Beaverstock, Citation2004, p. 162). More importantly, firms attempt to transfer knowledge or ‘corporate memory’ based on individual actors’ tacit and practical knowledge, socialization, corporate experience, leadership, and project management. They also connect the home and host country cultural and institutional settings and communicate daily with their corporate headquarters (Coe & Bunnell, Citation2003). Multicultural mediators are important in communication between workers from different social and cultural backgrounds (Beaverstock, Citation2004; Depner & Bathelt, Citation2005; Foster et al., Citation2015). For German firms investing in China, the so-called boundary spanners have built networks and mediated the cultural gap between the two countries (Depner & Bathelt, Citation2005). These include Chinese managers who had studied or lived in Germany for several years and Germans who have studied sinology or have Chinese spouses and have experience of Chinese business practices. Beaverstock (Citation2004) explained the importance of local managers who often act as mediators when subsidiary activities are eventually integrated into the core firm’s overall activities.

Both personal- and technology-based networking are essential to integrate and embed different corporate business cultures and increase local competitiveness. Communication in connectivity networks – socially thin, culturally neutral and the most weakly embedded mode of personal networking – focuses on specific topics rather than a personal domain (Grabher & Ibert, Citation2006). It is important to establish generalized reciprocity and an atmosphere of joint problem-solving and mutual support. Such interactions can be facilitated by technology-based networking methods such as virtual forums, group learning tools, and mobile chat/web-based discussion groups (Ambos & Ambos, Citation2009). This allows actors to codify, store and access knowledge, and is less sensitive to geographical distance than the personal-based networking method such as liaison personnel, temporary task forces and permanent teams.

FDI AND ECONOMIC INTERDEPENDENCE BETWEEN KOREA AND VIETNAM, AND THE REGIONAL IMPACT ON VIETNAM

FDI and regional economic development in Vietnam

The rising importance of South–South FDI has been noted with Asian countries attracting attention as home and host countries for FDI. Vietnam has become a major inward FDI destination owing to Asia’s economic growth. records the changing share of Asia and Southeast Asia in inward FDI stock. Asia’s global FDI share fell from 31.2% to 15.4% during the period 1980–2000, before rising to 23.9% in 2019. However, the Southeast Asian share within Asia rose from 8.0% to 30.8% during the period 1980–2019. Except for Singapore, Vietnam is a representative country that continues increasing its share of Southeast Asian countries inward FDI.

Table 1. Southeast Asian foreign direct investment (FDI) inward stock, 1980–2019.

From the mid-1950s to 1975 Vietnam was divided into the communist North and capitalist South. With the end of the Vietnam War the Communist Party of Vietnam came to power nationally. In 1986 the government and Communist Party adopted the Doi Moi policy, enacted the initial Foreign Investment Law to attract foreign capital and embarked on a transition from a planned to a socialist-oriented market economy. In 2005, the integrated legal framework – new Investment Law (No. 59/2005/QH1) and the Enterprise Law (No. 60/2005/QH11) – was revised to eliminate discrimination and provide uniform institutions for domestic and foreign investors (Ministry of Government Legislation, Citation2008). This legal and institutional reorganization was one of preconditions for joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007 an triggered a surge in investment by foreign companies. Increasing inward investment was accompanied by economic restructuring, job creation, labour productivity improvements, and the introduction of modern technology and management techniques (Koo, Citation2017). FDI-related sectors, mainly electronics, automobiles, motorcycles, garment, food and beverages, subsequently grew steadily.

As inward FDI increased, the share of employees in foreign-invested enterprises rose rapidly (). In 2000 almost 60% of employees worked for state-owned enterprises, with just over 10% for foreign-invested enterprises. In subsequent years many Vietnamese companies were privatized and non-state private enterprise employees rose from 30% to 60% of the total in 10 years, while the share of employees working for foreign companies grew from 11.5% in 2000 to 31.8% in 2019. In particular, nearly half of Vietnam’s female workforce works in foreign-invested companies, and of foreign company employees females account for 65.2%.

Table 2. Share of employees by the type of enterprises in Vietnam, 2000–19.

In addition to the increased dependence on foreign companies, the concentration in specific regions has significantly impacted Vietnam’s industrial and regional structures (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2010, Citation2011; Koo, Citation2017). Since the start of the open-door policy, the large inflow of FDI was concentrated in two economic regions: the Red River Delta and South East. Hanoi City, the capital and political centre, is in the Red River Delta, while the economic centre, Ho Chi Minh City, is in the South East. The share of registered capital of inward investors in these two regions increased from 65.6% to 78.1% from the periods 1988–2010 to 2011–19) (). Nguyen and Revilla Diez (Citation2017) verified that foreign firms prefer locating in two economic hubs and their surrounding provinces, Bac Ninh and Hai Phong, near Hanoi City, and Binh Duong and Dong Nai, near Ho Chi Minh City. The South Eastern region’s business climate is more market oriented, whereas the Red River Delta’s planning system has a stronger socialist heritage (Nguyen & Revilla Diez, Citation2017). Initially, inward FDI concentrated in southern Vietnam to avoid northern Vietnam’s socialist heritage. However, economic relations with the state and ties with the Communist Party and national and local government, as well as personal relationships with bureaucrats, have led to investment and outstanding growth in the Red River Delta since the 2000s. Until 2010, 20.1% of FDI capital was invested in the Red River Delta, and 45.5% in the South East, but after 2011, the Red River Delta’s share reached 39.5% compared with 38.6% in the South East (). As shows, the shares of enterprises and employees in these two areas have increased substantially since 2000.

Table 3. Regional share of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) in Vietnam.

Table 4. Regional distribution of enterprises and employees in Vietnam.

Korean investment in Vietnam and increasing economic interdependence

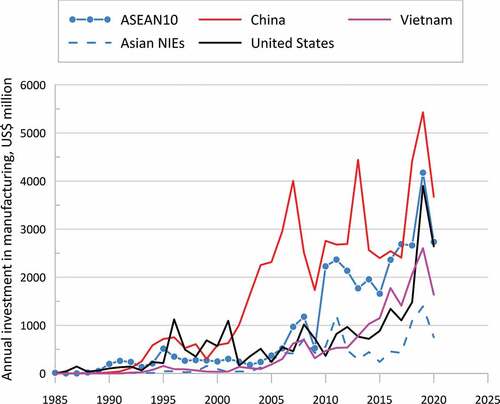

Korean TNCs’ relocation and plant expansion overseas began in the 1980s with the search for lower labour costs and new markets. FDI in China increased from the early 1990s and has topped the list since the 2000s (), with China accounting for 26.4% of manufacturing investment in the 1990s and 45.4% in the 2000s (Koo, Citation2017). However, in the 2010s Korean firms began reducing their Chinese investments and diversified into Southeast Asian countries. Although investment in Asian NIEs (Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan) has decreased after peaking in 2011, investment in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries has increased rapidly since the early 2000s. In the case of Vietnam FDI dates from textiles processing sector investment in the mid-1980s. Official Korean investment increased steadily after the establishment of Korea–Vietnam diplomatic relations in 1992 (Ji & Lee, Citation2007; Koo, Citation2017, Kim & Koo, Citation2018). Vietnam ranked fifth for Korean overseas manufacturing investment countries in the early 1990s, third in the 2000s and second after China in the 2010s (Koo, Citation2017). Meanwhile, Korea ranked first for inward foreign investment in Vietnam, surpassing Japan after 2014. Korea–Vietnam FDI flows gave rise to growing economic interdependence and complementarity. Korea’s so-called post-China strategy of manufacturing offshoring has intertwined with Vietnam’s inward foreign investment strategy.

Figure 2 Outward Korean manufacturing foreign direct investment (FDI) in selected countries, 1985–2017.

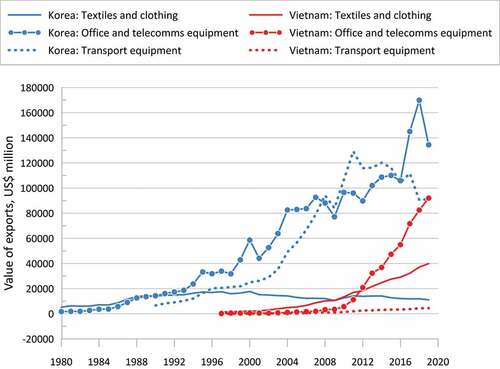

Rising Korean FDI in Vietnam resulted in the growth of exports between the two. As of the late 2010s, Vietnam ranked sixth in Korean export markets, while Korea ranked fourth in Vietnamese export markets. which reports the changing sectoral composition of Korean and Vietnamese merchandise exports by product reveals that Korean electrical and electronics (office and telecommunication equipment) and machinery (transport equipment) exports have expanded continuously since the 1980s. In the case of Vietnam textile and clothing exports predominated until 2012 when they were overtaken by the electrical and electronics. Major increases in foreign-invested manufacturing exports of mobile phones and home appliances saw the export value of office and telecommunication equipment reach 2.3 times that of textiles and clothing in 2019. Vietnam had become an unquestionable export platform in electronics sectors.

Figure 3. Korean and Vietnamese merchandise exports by sector, 1980–2019.

Korean firms concentrated in the same two economic regions as other inward investors (). In the early 1990s Korean firms concentrated in and around Ho Chi Minh City, centred on textile and garments subcontracting. At the same time Daewoo Corporation, a Korean multinational actively investing overseas, concentrated on Hanoi City through joint ventures with Vietnamese companies. For example, Vietnam-Daewoo Motor Company Limited – a joint venture of Daewoo Motors and Vietnam’s Ministry of Defence – was the first motor company in Vietnam. Daewoo-Hanel was another jointly established company involving Daewoo Electronics and Hanoi Electronics, a state-owned company in Hanoi City. These joint ventures expanded from labour-intensive sectors to the other construction and retail sectors and then diversified into technology-intensive manufacturing of electrical and electronic products from the mid-2000s. After the mid-2000s, major Korean firms investing in Vietnam included Samsung Electronics and LG Electronics. Over 40% of Samsung’s mobile phones were manufactured in Vietnam, and the company led Vietnam’s export market. Although Samsung Electronics had established household appliance factories in Ho Chi Minh City, the area around Hanoi City became the major production base for its main product of mobile phones after large-scale investments starting in the late 2000s. LG Electronics also invested in Vietnam from the mid-1990s, and, in 2015, it built a large-scale production complex in Hai Phong, a port city in northern Vietnam. Existing factories and subcontractors have relocated to this complex to make northern Vietnam the centre of their global mobile phone and household appliance production. Of companies registered in the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA) database in 2018, about 67% are located in the South East and about 20% in the Red River Delta ().

Figure 4. Distribution of Korean firms by province in Vietnam.

KOREAN TNC TRANSPLANTATION OF THE ELECTRONICS CLUSTER IN NORTHERN VIETNAM

Location factors for Korean TNCs in northern Vietnam

The fundamental motive of Korean TNCs’ investing in Vietnam was cost reduction. In achieving this goal they were aided by national and local governments incentives including land rent exemption for seven years, corporate income tax exemption for four years, R&D incentives and other investment credits (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2021). Korean TNCs located around Hanoi owing to the Communist Party’s intention of developing northern Vietnam, its significant bargaining power and well-aligned investment plans. The area chosen was designated as a bonded zone where raw materials are imported duty-free to manufacture exports, or as an area where equivalent benefits were provided by local government. The Vietnamese government has built road and other infrastructure facilities for TNCs or at least provided infrastructure support.

Another factor driving the choice of northern Vietnam was its proximity to China, and the fact that the main foreign-invested electronics goods in northern Vietnam manufactured mobile phones and household appliances whose parts and components are relatively small, light, and thin, enabling them to be imported via air and land from existing Chinese factories instead of sourcing locally (interview data).

For these reasons, large-scale Korean TNC investments were made in northern Vietnam. A subsidiary final assembly branch plant was established as a hub in a local cluster, and affiliates and suppliers entered together to become spoke companies in a hub-and-spoke satellite cluster that was, however, externally controlled and dominated by the Korean headquarters. This type of TNC cluster formation in overseas expansion with follow sourcing can be termed as the transplantation of satellite hub-and-spoke clusters.

Building satellite hub-and-spoke clusters through follow sourcing

TNCs can maintain competitiveness by owning their international and vertical mass production lines and maintaining supply chains. Overseas expansion with follow sourcing and satellite hub-and-spoke clusters have advantages for both Korean TNCs’ subsidiary plants and their subcontractors. To understand the underlying mechanisms, it is necessary to analyse the perspectives of both customers and suppliers as follows.

First, geographical proximity of production activities is a major cause of follow sourcing. Co-location or close location between a final assembly plant and its subcontractors can reduce not only logistic costs, but also allow immediate responses to changes in transaction volumes. For subcontractors, it is important not only to ensure product quality but also to comply with delivery schedules. According a second-tier supplier, although a TNC shares production plans with subcontractors, production volumes and supply requirements often fluctuate significantly. Consequently, Korean subcontractors entered Vietnam with the buyer and TNC subsidiaries and tried to locate in physical proximity so as to adjust quickly to sudden production schedule changes. Most raw and intermediate materials in Korean electronics TNCs would be imported from Korea or other countries rather than purchased from local Vietnamese companies. Although small and light intermediate goods can be sent as air freight, the complexity of local customs clearance in Vietnam makes it difficult for subcontractors to respond quickly to sudden changes. Consequently, subcontractors produce and stock inventories of raw materials and intermediate goods near the lead firm.

If a TNC guarantees the production plan, I could supply the products from outside of Vietnam because the parts and components are very small and light. But a TNC often changes volume and due date, and I have to meet the changed plans; this is too risky. So, it is better for me to prepare for the change in production plans by stocking some raw materials and producing and supplying close to the buyer.(interview with S8, an employee of a second-tier supplier)

Organizational proximity also influences follow sourcing in overseas expansion, as existing buyer–supplier and affiliate relationships can fall under the same conglomerate governance. Moreover, Korean corporations with strong internal vertical integration of affiliates conducted joint expansion with their affiliates during overseas investment (Lee & He, Citation2009). Not only subcontractors but also related affiliates entered with the lead firm due to hierarchical structure of Korean conglomerates’ and difficulty in changing their supply relationships. Established or sufficiently verified suppliers are crucial in overcoming difficulties in building cooperative trust with new local suppliers (Martin et al., Citation1995). Research shows that TNC managers rarely find local suppliers able to meet their quality requirements (Wrana & Nguyen, Citation2019). The importance of existing Korean hub-and-spoke production linkages was emphasized by not only by some lead firms’ expatriates and employees, but also by their suppliers and subcontractors in Vietnam. They referred to reasons such as quality control of raw materials and components, reduction in risk, uncertainty of finding new partners, and stable business relationship with reliable partners.

Probably, it is hard to find suitable local suppliers satisfying the standards of globally renowned Korean electronics companies. My company invested in Vietnam to supply raw materials when the buyer started to operate a subsidiary factory in 2008. Both mine and the buyer’s companies can have mutual benefits because the buyer could maintain the quality of raw materials in Vietnam, and my company can also secure a stable business relationship and strengthen trust.(interview with S1, a head of subsidiary at a supplier company)

We need suitable subcontractors that can meet our requirements. Asking existing suppliers to conduct business in Vietnam is the easiest way to formulate stable production networks here. But we cannot guarantee profit for the locals. So, in the early days of the decision to invest in Vietnam, we wouldn’t provide information to all suppliers, but only to some reliable ones with long-term trust.(interview with T2, an expatriate working at a Korean TNC)

Production stabilization is very important in large overseas production subsidiaries. Theoretically, finding local vendors with the lowest price could maximize profits, but it might be too risky. We don’t have any experience of those local companies, especially with their technology level, failure rate, and due dates. Therefore, we try to do business with companies with existing buyer–supplier relationships. We don’t want or need riskier business partners.(interview with T1, an expatriate working at a Korean TNC)

Since buyer companies cannot guarantee the future volume of transactions after overseas expansion with subcontractors, Korean TNCs have encouraged their subcontractors to selectively invest in Vietnam. In some cases, subcontractors are forced to follow their customer TNC, despite their reluctance, due to asymmetric inter-firm power relations. SME suppliers tend to depend on large customers with existing transactional relationships and which account for a majority of their sales. Nevertheless, once suppliers and subcontractors invest into northern Vietnam and are involved in TNCs’ production networks, the TNC guarantees minimal profits to subcontractors to avoid bankruptcy. However, they cannot provide direct financial support to all subcontractors. Instead, the lead firm provides various types of non-financial support to deal with problems that are difficult for SMEs to cope with in the Vietnamese environment, such as legal advice on Vietnamese institutions, labour issues, and bargaining with Vietnamese local and regional government.

The subsidiary hub firm in Vietnam may provide support for their local affiliates or subcontractors in case of legal and labour problems. In some cases, it is possible to oversee and manage bureaucratic affairs such as suggestions to and negotiations with Vietnamese local governments. There are various problems that cannot be solved by individual companies due to their foreign status and Vietnam’s socialist system, so we monitor and prepare for such issues, sometimes formally, sometimes informally.(interview with T4, a legal expatriate working at a Korean TNC)

LOCALIZATION EFFORTS OF TNCS, THEIR SUPPLIERS, AND INDIVIDUAL ACTORS

An important question concerns the extent and ways in which enclave economies centred on transplanted satellite-type hub-and-spoke clusters contribute to spillovers that give rise to upgrading through local technological absorption or improved R&D capabilities of Vietnamese actors alongside creating jobs.

Continuous import of components from the home country and previous production sites such as China slows and lowers the development intensity of Vietnamese local supply chains. Therefore, the Vietnamese government has sought to increase local content and local production. This initiative focused on promoting cooperation between FDI companies and local Vietnamese firms, particularly through domestic companies’ engagement with TNCs and local sourcing of parts and materials in the host country. To build stronger linkages between TNCs and local firms, a ‘Supporting Industry’ policy is facilitated through direct investment and tax benefits, which increase local sourcing in selected industrial sectors such as mechanical engineering, electronics, automobiles and so on (OECD, Citation2021).

Korean TNCs have increased their business linkages with local partners to meet the Vietnamese government’s requirements. However, localization and spontaneous spillovers pose challenges both for TNCs and local government. A commercial attaché O5 working at the Korean embassy indicated serious problems with the Vietnamese government’s lack of financial support for the upgrading of local firms and their limited skills and technological capabilities. TNC subsidiaries also complain about technological difficulties in working with Vietnamese domestic companies, in building trust in trading relationships and in ensuring compliance with global standards.

I worked as a purchasing manager. Subcontracting firms that previously had business relations in Korea entered Vietnam together. Particularly, in the case of core components, existing suppliers entered together with their customer companies. Relatively less important components can be sourced locally, amounting to about 40%. Guidance and learning programmes for Vietnamese suppliers have been provided to increase the proportion of local sourcing.(interview with T3, an expatriate working at a Korean TNC)

Spillovers from TNCs and their suppliers

TNCs’ state-of-the-art manufacturing and research facilities can play a leading role in local host economies. Production facilities or test beds with the latest technologies are sometimes built in newly established large-scale subsidiaries. New facility investments also serve as important resources for local technology and human resource training. For example, plastic materials have long been used for Samsung smartphone cases, but metal cases have become key to their production process since the mid-2010s. Machine tools for metal processing were installed on a large scale in newly established Vietnamese factories. Large-scale metal production infrastructure was built quickly, and production started ahead of that for the main headquarters’ factory. In response to the Vietnamese government’s request to promote local R&D, Samsung Electronics also built and is operating an R&D centre in northern Vietnam. Although direct TNC investment in R&D facilities is crucial for long-run local development, a step-by-step approach is required to actually increase local R&D capacity and varies by country, industrial sector, mode of FDI entry, time since initial investment, and other factors.

The fundamental determinants of technological spillovers include the technological gap between foreign and host economies and the absorptive capacity of domestic local firms. Similarities in technological level and business environment between home and host regions increase the potential for spillovers to local firms (Lipsey & Sjohölm, Citation2011). Considering the technological gap, production skill upgrades must precede technological development to form the basis for a firm’s manufacturing capabilities. Korean TNCs offer training programmes in production skills and new technology to both Korean and Vietnamese suppliers. They share workforce training programmes every year with suppliers in Vietnam, and subcontractors can dispatch employees to attend these programmes. As one interviewee working for a Korean TNC said, there are various TNC workforce training programmes such as one-day call-up classes at the TNC production facility, dispatching of experts to suppliers to transfer know-how, and two-week participation in the main corporate institute in Korea for human resource development. TNC suppliers can foster skilled workers without large expenditures on education and training, and these benefits go to both Korean employees and local Vietnamese workers. However, it is difficult to improve technical skills using these educational and training programmes consistently because many Vietnamese employees work for Korean TNC supplier companies for very short periods of time before moving to other companies.

In addition, TNC subsidiaries’ first or second-tier supplier companies are important in mediating relationships and technology transfer between TNCs and local Vietnamese firms and their employees. As explained above, it is very difficult for local Vietnamese companies to participate directly in TNCs’ production networks as first-tier or high-value production suppliers. Therefore, local firms supply parts and materials to Korean subcontractors to become stable partners. Moreover, Vietnamese workers in Korean subcontractor companies acquire skills and technologies through learning-by-doing and learning-by-interacting, enhancing Vietnam’s regional capabilities. Therefore, follow sourcing with subcontractors and direct TNC investment can play crucial roles in enhancing Vietnamese enterprises’ and employees’ manufacturing capacities and closing the technology gap between TNCs and host regions.

Other spillovers not directly linked to Korean TNCs’ supply chains link Korean SMEs and local Vietnamese firms through third-party actors like consulting firms. Korean consultancies in Vietnam supported the initial stage of Korean SMEs’ entry into the country, but they gradually added and expanded services to Vietnamese companies. Some Vietnamese investors with considerable capital but who lack information or experience in the electronics industry try to find suitable business partners through these consultancies. Both Korean and Vietnamese companies share reciprocal benefits by reducing production costs, stabilizing local production by hiring suitable local managers, acquiring advanced manufacturing technology or accessing existing business networks. In some cases, Vietnamese companies start a business by taking over bankrupted Korean companies; some do not change the name, take over existing Korean workers, and even hire more Korean managers. Vietnamese local firms thus absorb pre-existing trading networks and intangible assets of Korean companies, thereby reducing the instability of a business start-up. These examples show how knowledge and business activities embedded in Korean companies’ production networks can take root and be localized in Vietnam.

After retiring from a Korean TNC, I worked as the head of a subsidiary in China of the first-tier supplier in charge of coordinating overall production activities. That company invested in a new subsidiary in Vietnam, and I came here. I started a new consulting business in 2016. Based on my experience, I could support Korean SMEs that were setting up new subcontracting relationships with TNCs or trying to invest in Vietnam. I know what TNCs require of SMEs and what SMEs lack. I could thus consult on doing business with TNCs and managing or solving local problems. Recently, I began mediating between Vietnamese manufacturing companies and Korean SMEs. I could link Korean companies with some Vietnamese who have sufficient capital but do not have enough operational production know-how. For Vietnamese manufacturers, this is a means to overcome shortcomings and acquire foreign manufacturing knowledge easily.(interview with F2, a business consultant in Vietnam)

Role of individual actors and their networks

Individual actors play important roles in the localization of transplanted clusters. Korean TNC expatriates regularly visit or communicate with headquarters and act as both intermediators in the headquarter–subsidiary relationship, enable the transfer business standards and serve as means of control over the branch plant. They usually occupy managerial positions and return to Korea after a fixed period of three to five years, although some settle in Vietnam after retiring or quitting Korean companies and run other businesses connected with Korean firms, as in the case of interviewee F2. In contrast, local employees with Korean nationality are not dispatched from Korea, but are recruited by local subsidiaries in Vietnam. They are usually younger than expatriates and occupy staff positions in TNCs and their supplier companies. Many of them moved to Vietnam with their parents, and were educated in Vietnam, while others majored in Vietnamese language at a Korean university. Some married Vietnamese citizens and settled there. Their business activities are centred around their proficiency in the Vietnamese language; thus, their major roles are as intermediaries and translators and as boundary spanners connecting Vietnamese and Korean languages and cultures. Expatriates usually follow the directions set by their headquarters and sometimes modify and adjust the decisions made by subsidiaries. Local Korean employees help communicate and explain these directives to Vietnamese workers.

Former large firm or TNC expatriates are usually now in their 50s or older, and can be called early pioneers. They run subcontracting factories associated with their former Korean TNCs or other firms, started new businesses, or found new expatriate positions in other firms. For example, members of Korean TNC Daewoo acted as pioneers of Korean investment and boundary spanners. They have stayed in Vietnam for a long period, changing their roles and positions according to business conditions and local environmental changes contributing to the embeddedness of Korean enterprises and improving the Korean investment environment.

In the early 1990s, I was sent to Vietnam as a regional expert of Daewoo Corporation. I have worked as an expatriate for about 7 years, but as the management situation of Daewoo got worse, I even participated in the company’s disinvestment. I was later appointed as a local president and ran a factory related to Daewoo Electronics, and I acquired that factory and took over as a CEO and managed it. A few years later, the factory was handed over to the Vietnamese manager again. Some former Daewoo veterans are now in the position of branch managers of other companies.(interview with S7, an expatriate and former Daewoo employee)

Workers communicate within the office through intranet systems or face-to-face interaction. However, employees cannot access the intranet outside the office without authorization, and suppliers and other extra-firm actors do not have access to the formal system. To ensure smooth functioning and communicate with all these actors frequent use is made of mobile chat applications such as Kakaotalk, which is popular among all Koreans and the Korean community in Vietnam (Koo, Citation2020). Such real-time mobile-based social networking services have contributed greatly to interaction between various actors. Previously, Vietnamese people did not use Kakaotalk, but an increasing number of Vietnamese employees working with Korean firms now use this app to discuss work issues and share information with Koreans. Chat services are used informally on a one-to-one or group chat basis, following which they communicate officially via email and various documents. Sometimes, employees in Korean headquarters and expatriate managers in Vietnam use this method to overcome time, distance, geographical, and cultural gaps.

We usually talk a lot about work using Kakaotalk group chats because we can’t use the intranet communication systems outside the office. We use voice calls for urgent things of course. But group chatting has enabled us to interact one-to-many, which is very useful in information sharing.(interview with S2, a local employee with Korean nationality working at a Koran TNC supplier firm)

Intranet systems require personal computer access and login, but Kakaotalk can be used anywhere with mobile phones in real time. It is also used in official business communication with headquarters and interaction within branches. Of course, we do not use it for very important decisions.(interview with T3, an expatriate working at a Korean TNC)

Official technical infrastructure plays a central role in intra-organizational knowledge transfer as it allows employees to codify, store and access knowledge. The unofficial mobile application helps with real-time communication with employees, including extra-firm actors, anywhere. Strong organizational control and centre-accumulated decision-making processes can overcome geographical distance through expatriates control over the local branch. Cultural distance in working styles between the Koreans and Vietnamese remains, but mobile communication via group chatting can close the communication gap.

CONCLUSIONS

Although positive factors such as low labour cost, proximity to China, and relatively stable social institutions and government support attract FDI to Vietnam, investment is concentrated in clusters with a transplanted hub-and-spoke structure with attempts to increase local sourcing. Although Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam have abundant cheap labour, their technological potential is low. Therefore, foreign-investment companies enter these countries with their suppliers and establish satellite hub-and-spoke clusters. Although there is considerable future market potential, current market demand in these countries is not at par with that of China. As China has strong bargaining power as well as abundant workers and huge markets, it is able to enforce the ‘obligated embeddedness’ on TNCs in the shape of joint ventures and local sourcing.

To ensure that it does not remain just a satellite export platform, Vietnam must continue to localize production activities and upgrade technology and human resources. To succeed, regional production bases should be established and the gap with global technology standards reduced. This study of TNC cluster transplantation through follow sourcing in latecomer host regions and revealed the role of localization and spillovers. Investments by TNCs and their suppliers are essential mediators in improving the manufacturing capacity of local Vietnamese firms and individual actors as stable suppliers of low- and middle-value parts and materials and provide them with opportunities to connect and integrate with GPNs. In addition, various individual actors embedded in Korean company networks are trying to link with Vietnamese manufacturing enterprises and increase the technological capabilities of local clusters.

For latecomer developing countries with a low degree of regional competitiveness, transplanted satellite hub-and-spoke clusters can serve as initial bases for economic development despite the risks of the reproduction of externally controlled export enclaves. Transplanted clusters with follow sourcing can serve as an intermediate stage between the development of an externally controlled satellite cluster and an advanced cluster with thicker local networks. Although the local networks, sourcing and spin-offs, are still weak in northern Vietnam’s electronics cluster, spillovers from TNCs and their suppliers are empowering local Vietnamese companies and increasingly connecting them with GPNs. Therefore, strategic coupling between TNCs and regional assets is still significant in spite of GPNs’ lead firm-centric focus and the bargaining power imbalance between TNCs and host developing economies. The economic catch-up process in developing Asian countries has pointed out the importance of selective engagement with GVCs/GPNs in an initial opening to FDI, followed by restrictions, localization and re-integration (Lee, Citation2019). In high-end sectors Vietnam can be regarded as having gone through the opening to FDI with the transplantation of clusters through follow sourcing, and as advancing to the next step of localization with the support of spillovers from TNCs and their suppliers. For this reason the transplantation and localization of clusters through follow sourcing affords another South–South FDI model for latecomer developing Southeast Asian countries alongside the Chinese model of ‘obligated embeddedness’ based on national and regional bargaining power in engaging with GPNs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the editors, Professor Michael Dunford and Professor Sam Ock Park, for important feedback and editorial help, and the anonymous referees for their valuable comments.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.5 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2022.2058569

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Ambos, T. C., & Ambos, B. (2009). The impact of distance on knowledge transfer effectiveness in multinational corporations. Journal of International Management, 15(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2008.02.002

- Anwar, S., & Nguyen, L. P. (2010). Foreign direct investment and economic growth in Vietnam. Asia Pacific Business Review, 16(1–2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438590802511031

- Anwar, S., & Nguyen, L. P. (2011). Foreign direct investment and export spillovers: Evidence from Vietnam. International Business Review, 20(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.11.002

- Bathelt, H., & Henn, S. (2014). The geographies of knowledge transfers over distance: Toward a typology. Environment & Planning A, 46(6), 1403–1423. https://doi.org/10.1068/a46115

- Beaverstock, J. V. (2004). ‘Managing across borders’: Knowledge management and expatriation in professional service legal firms. Journal of Economic Geography, 4(2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/4.2.157

- Boschma, R. A. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Chandra, V., Lin, J. Y., & Wang, Y. (2013). Leading dragon phenomenon: New opportunities for catch-up in low-income countries. Asian Development Review, 30(1), 52–84. https://doi.org/10.1162/ADEV_a_00003

- Coe, N. M., & Bunnell, T. G. (2003). ‘Spatializing’ knowledge communities: Towards a conceptualization of transnational innovation networks. Global Networks, 3(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00071

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Genc, M. (2008). Transforming disadvantages into advantages: Developing-country MNEs in the least developed countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6), 957–979. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400390

- Depner, H., & Bathelt, H. (2005). Exporting the German model: The establishment of a new automobile industry cluster in Shanghai. Economic Geography, 81(1), 53–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2005.tb00255.x

- Ettlinger, N. (2003). Cultural economic geography and a relational and microspace approach to trusts, rationalities, networks, and change in collaborative workplaces. Journal of Economic Geography, 3(2), 145–171. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/3.2.145

- Export–Import Bank of Korea. Statistics of foreign direct investment in Korea (http://stats.koreaexim.go.kr)

- Florida, R., & Kenney, M. (1991). Transplanted organizations: The transfer of Japanese industrial organizations to the U.S. American Sociological Review, 56(3), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096111

- Foster, P., Manning, S., & Terkla, D. (2015). The rise of Hollywood East: Regional film offices as intermediaries in film and television production clusters. Regional Studies, 49(3), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.799765

- Frigant, V., & Lung, Y. (2002). Geographical proximity and supplying relationships in modular production. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 26(4), 742–755. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00415

- Gao, B., Dunford, M., Norcliffe, G., & Liu, W. (2019). Governance capacity, state policy and the rise of the Chongqing notebook computer cluster. Area Development and Policy, 4(3), 321–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2018.1544465

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam. ( each year). Statistical yearbook of Vietnam. Statistical Publishing House of Vietnam. https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/homepage/

- Gereffi, G. (1999). International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics, 48(1), 37–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00075-0

- Grabher, G., & Ibert, O. (2006). Bad company? The ambiguity of personal knowledge networks. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(3), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi014

- Hess, M. (2004). ‘Spatial’ relationships? Toward a reconceptualization of embeddedness. Progress in Human Geography, 28(2), 165–186.

- Holl, A., Pardo, R., & Rama, R. (2010). Just-In-Time manufacturing systems, subcontracting and geographic proximity. Regional Studies, 44(5), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400902821626

- Ivarsson, I., & Alvstam, C. G. (2005). The effect of spatial proximity on technology transfer from TNCs to local suppliers in developing countries: The case of AB Volvo in Asia and Latin America. Economic Geography, 81(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2005.tb00256.x

- Ji, H., & Lee, S. (2007). Internationalization Strategies of Production Capital and Locational Determinants: Korean Textile and Clothing Foregin Direct Investment in Vietnam. The Geographical Journal of Korea, 41(4), 469–483.

- Kim, S., & Koo, Y. (2018). Korean self-employment immigrants and Korean community networks in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of the Korean Geographical Society, 53(3), 387–403. in Korean.

- Kim, S. (2020). Formation and change of production network based on customer-following overseas expansion of Korean subcontractors: Electronics industries in Hanoi Red River Delta, Vietnam. Journal of the Economic Geographical Society of Korea, 23(2), 147–165. in Korean. https://doi.org/10.23841/egsk.2020.23.2.147

- Kleibert, J. M. (2016). Global production networks, offshore services and the branch-plant syndrome. Regional Studies, 50(12), 1995–2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1034671

- Koo, Y., & Park, S. O. (2012). Structural and spatial characteristics of personal actor networks: The case of industries for the elderly in Korea. Papers in Regional Science, 91(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5957.2011.00370.x

- Koo, Y. (2017). Korean enterprises’ foreign direct investment to Vietnam and changes on Vietnamese industrial structure and regions. Journal of the Korean Geographical Society, 52(4), 435–455. in Korean.

- Koo, Y. (2020). Living as an expatriate’s spouse in Vietnam: From a ‘trailing wife’ to a mediator of community networks through social network services. Journal of the Korean Geographical Society, 55(3), 313–327. in Korean. https://doi.org/10.22776/kgs.2020.55.3.313

- Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA). (2018). Directory of foreign-invested Korean Companies.

- Lee, K., & He, X. (2009). The capability of the Samsung group in project execution and vertical integration: Created in Korea, replicated in China. Asian Business & Management, 8(3), 277–299.

- Lee, K. (2019). The art of economic catch-up: Barriers, detours and leapfrogging in innovation systems. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108588232

- Lipsey, R. E., & Sjohölm, F. (2011). South–South FDI and development in East Asia. Asian Development Review, 28(2), 11–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2050384

- Liu, W., & Dicken, P. (2006). Transnational corporations and ‘obligated embeddedness’: Foreign direct investment in China’s automobile industry. Environment & Planning A, 38(7), 1229–1247.

- Lyberaki, A. (2011). Delocalization, triangular manufacturing, and windows of opportunity: Some lessons from Greek clothing producers in a fast-changing global context. Regional Studies, 45(2), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903380408

- Mackinnon, D. (2012). Beyond strategic coupling: Reassessing the firm–region nexus in global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr009

- MacKinnon, D., & Cumbers, A. (2019). An introduction to economic geography: Globalisation, uneven development and place (Third ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315684284

- Markusen, A., & Park, S. O. (1995). Generalizing new industrial districts: A theoretical agenda and an application from a non-Western economy. Environment & Planning A, 27(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1068/a270081

- Markusen, A. (1996). Sticky places in slippery space: A typology of industrial districts. Economic Geography, 72(3), 293–313. https://doi.org/10.2307/144402

- Martin, X., Mitchell, W., & Swaminathan, A. (1995). Recreating and extending Japanese automobile buyer'supplier links in north America. Strategic Management Journal, 16(8), 589–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250160803

- Millar, J., & Salt, J. (2008). Portfolios of mobility: The movement of expertise in transnational corporations in two sectors — Aerospace and extractive industries. Global Networks, 8(1), 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2008.00184.x

- Ministry of Government Legislation. (2008). A study on investment–financial legislation in Vietnam. in Korean.

- Nguyen, T. X. T., & Revilla Diez, J. (2017). Multinational enterprises and industrial spatial concentration patterns in the red river delta and Southeast Vietnam. The Annals of Regional Science, 59(1), 101–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0820-y

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021). SME and entrepreneurship policy in Viet Nam. https://doi.org/10.1787/30c79519-en

- Park, S. O. (1996). Networks and embeddedness in the dynamic types of new industrial districts. Progress in Human Geography, 20(4), 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913259602000403

- Park, S., & Koo, Y. (2021). Impact of proximity on knowledge network formation: The case of the Korean steel industry. Area Development and Policy, 6(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2020.1797518

- Pavlínek, P., & Žížalová, P. (2016). Linkages and spillovers in global production networks: Firm-level analysis of the Czech automotive industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(2), 331–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu041

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2007). Variegated capitalism. Progress in Human Geography, 31(6), 731–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507083505

- Schwabe, J. (2020). From ‘obligated embeddedness’ to ‘obligated Chineseness’? Bargaining processes and evolution of international automotive firms in China’s new energy vehicle sector. Growth and Change, 51(3), 1102–1123.

- Thomsen, L. (2007). Accessing global value chains? The role of business–state relations in the private clothing industry in Vietnam. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(6), 753–776. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm028

- World Trade Organization (WTO). International trade statistics. http://www.wto.org/statitics.

- Wrana, J., & Nguyen, T. X. T. (2019). ‘Strategic coupling’ and regional development in a transition economy: What can we learn from Vietnam. Area Development and Policy, 4(4), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2019.1608838

- Yeung, H. W. (1995). Qualitative personal interviews in international business research: Some lessons from a study of Hong Kong transnational corporations. International Business Review, 4(3), 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/0969-5931(95)00012-O

- Yeung, H. W., & Coe, N. M. (2015). Towards a dynamic theory of global production networks. Economic Geography, 91(1), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12063