?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Foreign direct investment (FDI) and regional development are mutually interwoven phenomena. This paper introduces an analytical framework to investigate the interaction mechanism between FDI and regional industrial structure. This framework posits first that FDI generally has a significant influence on the industrial structure in the region concerned, specifically through intervening mechanisms such as capital supply, active selection, passive competition, product linkage, imitation and demonstration and employee flows. Secondly, the industrial structure, in turn, also affects FDI flows through mechanisms including market demand, factor supply and policy or institutional factors. Finally, there are bi-directional interactions; using a spatial interaction framework, the present study applies and tests a simultaneous equation model and a spatial Durbin model to analyse empirical data from 15 urban regions in the Pearl River Delta mega-city region (PRD) in China spanning the period 2005–2018. The key findings from this multi-scalar analysis are: (i) there are substantial interactive effects between FDI and industrial structure, with the rationalisation and upgrading of the industrial structure significantly promoting FDI inflows into the PRD; (ii) FDI inflows, in turn, contribute to the reinforcement and upgrading of the industrial structure in the PRD; and (iii) the interactions between FDI and industrial structure exhibit significant spatial-economic growth effects. We also find that moderator factors, including independent R&D level, market size, marketisation level, labour cost, infrastructure and government expenditure, have discernible impacts on FDI inflows and the rationalisation and upscaling of the industrial-economic structure in the area concerned. Finally, we note that, in our study, significant spatial dependence effects among urban areas inside the PRD area are observed and modelled. The discussion of the empirical findings leads to the identification of several important policy implications and lessons for regional development strategies from an FDI perspective.

1. Setting the scene

In the past decades, economic globalisation has had a profound impact on economies worldwide. It has fostered international trade and has reduced barriers to bilateral investments (Mencinger, Citation2003; Piketty, Citation2015; Shangquan, Citation2000). Worldwide, both inbound and outbound foreign direct investments (FDI) have experienced substantial growth in recent decades (OECD, Citation2002; WIR, Citation2020), often accompanied by increased international trade and migration (Aroca & Maloney, Citation2005; Capello et al., Citation2011; Federici & Giannetti, Citation2010; Gheasi et al., Citation2013; Kugler and Rapaport Citation2007). In this context, cross-border investments play a central role.

The existing body of literature on foreign direct investment (FDI) has been significantly influenced by Dunning’s (Citation2001) eclectic theory, which asserts that ownership (monopolistic) advantages, location advantages and internalisation advantages are critical determinants for the selection of FDI locations and entry modes globally (Andreu et al., Citation2017; Cheng, Citation2006; Dunning et al., Citation2007; Kang & Annd Jiang, Citation2012; Sen, Citation1989). However, there has been comparatively less focus on examining the regional and place-based impacts of large-scale inward and outward FDI in scientific research (see Liu et al., Citation2014; Tan et al., Citation2016). Clearly, there are a few notable examples of region-based FDI studies. The spatial distribution of FDI across different regions within a country can lead to regional development disparities (Bhupatiraju, Citation2020; Malerba et al., Citation1997; Paci & Usai, Citation1999). A notable study conducted by Resmini (Citation2017) explored the patterns of inward FDI across regions and sectors in the EU, examining the regional drivers and factors influencing FDI attractiveness. The present study focuses on investigating the interactions between FDI and industrial growth in the Pearl River Delta in China, one of the world’s major and rapidly developing industrial regions.

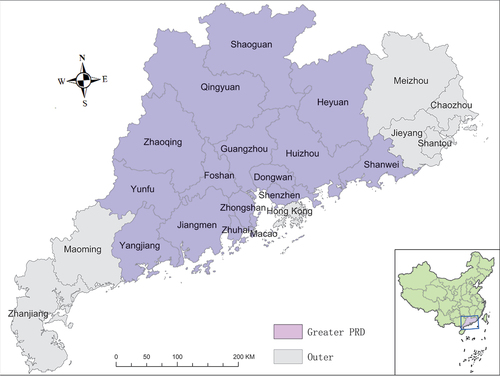

The Pearl River Delta (PRD) started as a geographically demarcated area in 1994, initially comprising nine urbanised growth areas in southern China. This area was extended in 2017 to form the Greater Pearl River Delta, encompassing 15 urbanised regions (see ). It comprises numerous economic activities in the manufacturing and trade sectors and has evolved into a major hub for economic development and international trade. In the present study, we will mainly focus on FDI effects in the latter mega-city area, abbreviated as PRD.

Figure 1. The Greater PRD composed of 15 urban areas (this map is based on the standard map with review number GS (2020) 4619 from the Map Technical Review Centre of the Ministry of Natural Resources of China).

While many studies have examined the interaction between FDI and industrial structure at the national level, it remains uncertain whether the same dynamics apply to mega-city regions like the PRD, characterised by high economic density and FDI concentration. Additionally, the presence of relevant spatial spillover effects within the PRD and the possibility to empirically test these propositions at a sub-regional scale have received limited attention in the extant literature.

This paper aims to address this research gap by investigating the PRD, one of the economically most developed regions in China with a significant concentration of FDI, as an interesting case study (see also Yeung, Citation2001). Our objective is to establish and test an operational framework for understanding the multi-faceted interaction between FDI and the industrial structure in this context, drawing upon the rich existing literature. The novelty lies in the treatment of intra-areal FDI effects. To achieve this, we collect a rich appropriate dataset (2006–2019), employ a simultaneous equations model (SEM) and a spatial Durbin model (SDM) and conduct several empirical econometric analyses. These analyses not only assess the applicability of the conceptual framework but also yield policy implications relevant to the examined region.

The study is organised as follows. After the aims and scope of the paper (Section 1), we describe the study context (Section 2), followed by a systematic literature review (Section 3). Next, in Section 4 the analytical framework is sketched out, followed by a data and modelling section (Section 5). The findings are discussed and interpreted in Section 6, while Section 7 provides conclusions.

2. The context

Over the past decades, China has experienced a notable increase in both inbound and outbound foreign direct investment (FDI; Gunby et al., Citation2016; Latorre et al., Citation2018; Song et al., Citation2020; Yao et al., Citation2016). While China’s FDI performance is undoubtedly remarkable, it raises the question of whether certain regions have benefitted more from the locational and internalisation aspects of FDI. This study focuses on examining the industrial-economic consequences of Chinese FDI within one of the country’s prominent mega-regions, namely the Pearl River Delta, which encompasses a significant portion of Southeast China. The question is now whether FDI effects are uniformly distributed in this area.

Since the initiation of political-economic reform and opening-up in 1978, China has achieved significant economic development milestones and has attracted substantial foreign direct investment (FDI) from around the world. According to the 2022 World Investment Report by UNCTAD (WIR Citation2020), China’s global FDI outflow reached $1.71 trillion in 2021, with a total stock of $37.06 trillion by that year. China’s FDI inflow accounted for 10.59% of the global flow and 6.85% of the global stock, ranking second in FDI inflows and third in stock globally. The inflow of FDI has played a pivotal role in shaping China’s industrial structure. The favourable investment climate has attracted an increasing number of multinational enterprises (MNEs) to invest in new industries within China, thereby promoting industrial development (Cole et al., Citation2011; Ning, Citation2009; Stallkamp, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2010; Zheng et al., Citation2010, Citation2022b). Furthermore, FDI has contributed to the upgrading of China’s industrial structure (Costantini et al., Citation2013; Feldman & Audretsch, Citation1999; Grimes & Yang, Citation2018; Ning, Citation2009), with the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region standing out as a notable example of successful regional development.

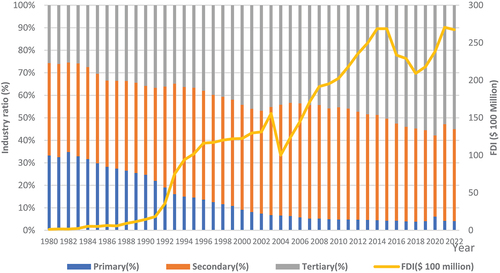

Under China’s reform and opening-up policy, the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region has over the past decades emerged as a significant hub for foreign direct investment (FDI) due to its favourable coastal location and environmental advantages (Da Silva-Oliveira et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2010). It has established itself as a prominent FDI cluster, both within China and globally. The PRD has achieved a leading position in terms of attracting FDI and driving industrial structure upgrading. According to data from the Guangdong Statistics Bureau, in 2022, FDI inflows into the PRD reached $26.47 billion, accounting for 14.0% of China’s total. The accumulated FDI inflow amounted to $544.78 billion, constituting 21.3% of the national total. Additionally, the cumulative number of foreign-owned firms reached 198,918, representing a 17.7% share nationally. Benefiting from national preferential policies and the inflow of FDI, the PRD has undergone a remarkable economic transformation within a few decades, transitioning from an agriculture-dominated region to a manufacturing and services-driven powerhouse. It has evolved into one of China’s largest industrial clusters, with significant changes in its industrial structure (primary-secondary-tertiary). The ratio shifted from 33.2:41.1:25.7 in 1980 to 4.1:40.9:55.0 in 2022, as depicted in .

Figure 2. The evolution of industry structure and FDI inflows in the PRD.

This illustrates a striking correlation between the industrial structure and FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) inflows in the Pearl River Delta (PRD). As FDI inflows increased in the PRD, the industrial structure underwent upgrades, and vice versa, albeit with some annual fluctuations in FDI flows. This underscores its robust development resilience, suggesting a significant interaction between FDI inflows and the industrial structure at a regional scale.

Previous research (Barry, Citation1999; Blomström & Kokko, Citation1998; Blomström & Persson, Citation1983; Borensztein et al., Citation1998; Branstetter & Feenstra, Citation2002; Wang et al., Citation2020; Zhao & Niu, Citation2013) has shown that FDI inflows can have a positive impact on a host country’s industrial structure through various channels. These include capital supply, technology spillovers, imitation and demonstration effects and personnel flows. Furthermore, FDI can contribute to diversifying and supporting host economies, enhancing their resilience and reducing vulnerability to adverse economic shocks (Jones & Wren, Citation2006). Another body of literature (Barrell & Pain, Citation1999; Braunerhjelm & Svensson, Citation1996; Devereux et al., Citation2003; Head et al., Citation1995; Jones & Wren, Citation2006) has emphasised the influence of the industrial structure on the utilisation of FDI. Additionally, some scholars have proposed the concept of an interaction between the volume of FDI inflows and the existing industrial structure in host countries (Lin & Kwan, Citation2011; Yin et al., Citation2011; Zhao & Jia, Citation2017). In Section 3, we will systematically summarise the wealth of FDI-related studies and offer a more detailed literature overview as the basis for our empirical research focused on urban areas inside the PRD.

3. Literature review

The literature on FDI effects is rich. In this section we will provide a short review, from three distinct angles: (i) FDI effects on the economy; (ii) effects of industrial development on FDI; and (iii) interaction effects between FDI and industrial structure. The regional and locational dimensions appear to be largely underrepresented (Yeung, Citation2001). In the existing literature regarding the impact of FDI on the industrial structure, numerous scholars argue that FDI significantly contributes to enhancing the host country’s industrial landscape (Carkovic & Levine, Citation2002; Ford et al., Citation2008; Lee & Tcha, Citation2004; Mencinger, Citation2003; OECD, Citation2002). Nevertheless, the extent of this enhancement is closely tied to factors such as the nature of FDI, the industry it enters and the timing of its introduction into the host country. According to Blomström and Persson (Citation1983), one way foreign investment reinforces the existing industrial structure is through technology spillover effects. Furthermore, Borensztein et al. (Citation1998) integrated FDI as a production factor in an endogenous economic growth model and identified positive impacts of FDI inflows on host countries’ industrial structure upgrades. Barry (Citation1999) conducted research in Ireland, Spain, Portugal and the United Kingdom, comparing FDI absorption and industrial structure. This study revealed that export-oriented MNEs with high levels of human capital had a significant impact on industrial development and structural upgrading. Branstetter and Feenstra (Citation2002) discovered that FDI facilitated adjustments in the host country’s industrial structure through technology spillover effects, both in developed and developing nations. Das (Citation2007) highlighted the short- and long-term effects of FDI on a host country’s industrial structure. In the short-term, FDI may lead to a technology monopoly but, in the long-term, it can generate technological spillover effects that bolster the host area’s industrial structure.

Zhao and Niu (Citation2013) discussed the impact of FDI on China’s industrial structure from two perspectives: scale and structure. They proposed that China should attract more foreign capital flows into the tertiary industry to facilitate the country’s overall industrial structure upgrade. In a separate study, Wang et al. (Citation2020) utilised spatial econometric methods to explore the relationship between foreign trade volume and FDI in elevating China’s regional industrial structure. Their findings indicated that China’s imports, exports, FDI and reinforcement of industrial structure played crucial roles in driving the upgrade of the industrial structure. However, the spatial spillover effects of FDI were not found to be significantly clear.

Nevertheless, some scholars argue that FDI has no significant – or even negative – impacts on optimising the industrial structure in the host country (Blomström & Kokko, Citation1998; Forte & Moura, Citation2013; Grilli & Milesi-Ferretti, Citation1995; Haddad & Harrison, Citation1993; Javorcik, Citation2004; Lensink & Morrissey, Citation2006; Lim, Citation2001; Mohnen, Citation2001; Pessoa, Citation2007; Zheng et al., Citation2022a). Hunya (Citation2002) claimed that FDI usually enters host country industries with a comparative export advantage and does not typically affect changes in the country’s traditionally advantageous industries. In his view, FDI has no significant impact on the overall industrial structure. In this context, David et al. (Citation2002) found that FDI inflow diverted human resources and market share from enterprises outside the region. This weakened the competitiveness of these enterprises, negatively impacting the industrial structure. Lastly, Tanna (Citation2009) found that a host country relying heavily on FDI would experience a fixed lock-in of production processes, hindering overall industrial upgrading.

Next, we note that research regarding the effects of the prevailing industrial structure on FDI is limited (Forte & Moura, Citation2013). Only a few studies argue that rationalising the industrial structure can promote FDI inflow (Mohnen, Citation2001; Pessoa, Citation2007; Vissak & Roolaht, Citation2005). However, the amount of FDI inflow is typically influenced by factors such as the type of FDI, the distribution of industries in the host region and government policies. Wu and Radbone (Citation2005) and Huang and Wei (Citation2014) found that the level of industrial concentration in a region significantly affects the location selection of foreign investment. FDI inflows could occur only when the comparative advantages of a local industrial agglomeration coincided with those of foreign investment. Lin and Kwan (Citation2011) concluded that the allocation of FDI among industrial sectors had self-reinforcing effects. For industries where state-owned enterprises received preferential treatment through market access, FDI entry was hindered, while labour-intensive and export-oriented sectors could attract more FDI.

Finally, only a few studies on the interplay between FDI and the (regional) industrial structure exist in the literature (e.g., Baharumshah & Almasaied, Citation2009; Beaudry & Schiffauerova, Citation2009; Copeland & Taylor, Citation2004; Dean et al., Citation2009; Glaeser et al., Citation1992; He & Wang, Citation2012; Zhang & Fu, Citation2008). These studies mainly employ econometric methods to quantify the interaction between the two and they have not arrived at a consistent conclusion. For example, Yin et al. (Citation2011) conducted data-based research on the interaction between China’s industrial upgrading and FDI, utilising cointegration analysis and dynamic variance decomposition techniques. Yin found a structural and stable relationship between the two; however, it appeared that industrial strengthening relied more on indigenous changes. In another study, Zhao and Jia (Citation2017) used a nonlinear Granger causality test to examine the relationship between FDI and industrial structure. Their findings indicated a one-way nonlinear Granger relationship, with FDI impacting the industrial structure, and a one-way non-linear relationship for the effects of industrial structure on FDI.

Our literature review shows that research on the relationship between FDI and industrial structure encompasses both theoretical and empirical studies, with econometric analyses being widely utilised. However, due to variations in analytical perspectives, research methods, theories applied and developmental contexts, the conclusions reached differ as well. Drawing upon the aforementioned literature, we can draw the following conclusions. Firstly, the impact of FDI on existing industrial structure adjustment is generally uncertain. Most studies suggest that FDI can reinforce industrial structure adjustment by capital accumulation and capital spillover effects, thereby playing a significant role in promoting industrial structure upgrading (Teng et al., Citation2023). However, a small portion of empirical research argues that FDI may hinder host countries’ industrial structure adjustment by intensifying market competition, limiting independent innovation and restricting capital flows. Additionally, a few studies propose that FDI has no effect on industrial structure adjustment. Secondly, proponents of FDI’s ability to promote industry development assert that the effects of FDI on industrial structure adjustment vary. These effects are influenced by the type of FDI, the industry absorbing the FDI, regional characteristics and the timing of FDI inflows. Thirdly, advocates for the rationalisation and upscaling of the prevailing industrial structure argue that this promotion is contingent on the type, volume and industrial structure of FDI, as well as government policies. Lastly, existing research rarely examines the interaction between FDI and industrial structure comprehensively.

It is noteworthy that spatial effects are often neglected and that most studies predominantly focus on national-level cases, with limited research at the sub-national level. Our study will zoom in on a spatially disaggregated level, in particular the urban areas in the PRD. This specific focus is rarely found in the extant literature on FDI.

In summary, both in theory and reality, FDI mobility and industrial structure adjustment are intricate spatial-economic processes intertwined with multiple factors, mechanisms and effects at both local and spatial levels (see e.g., Bailey et al., Citation1994; Casi & Resmini, Citation2014; Phelps & Raines, Citation2003). Building upon this foundation, this article will construct an analytical framework to explore the interaction mechanism between FDI and industrial structure. Subsequently, relevant variables impacting FDI location development and industrial structure will be selected, followed by the development of simultaneous equation and spatial econometric models (e.g., Autant-Bernard & LeSage, Citation2011; LeSage & Pace, Citation2010). The empirical analysis will primarily focus on the Pearl River Delta (PRD), one of the largest clusters of FDI and industry concentration in China, aiming to conduct a quantitative study that explores the interaction between FDI and industrial structure and derive valuable policy implications.

4. Analytical framework

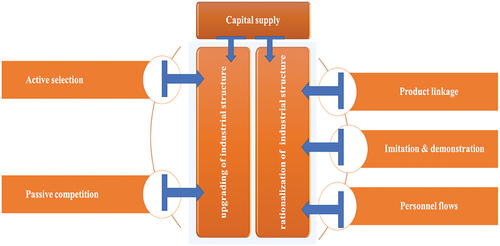

Based on our literature review with a tripartite subdivision into three strands of literature, we can summarise and design the impact mechanisms of FDI on current industrial structures, as well as the reciprocal impact mechanisms of industrial structure on FDI flows. FDI influences the industrial-economic structure through mechanisms such as capital supply, active selection, passive competition, product linkage, imitation and demonstration and personnel flows. Conversely, the industrial structure can be influenced by FDI through mechanisms such as market demand, factor supply and policy systems. Drawing upon these mechanisms, we can construct an operational framework to analyse the interaction between FDI and industrial structure.

4.1. The impact mechanism of FDI on industrial structure

As a carrier of high-quality capital, advanced technology, machinery and equipment and business management experiences, FDI can replenish capital and improve productivity by supplying capital, technology and industrial linkages. It can also assist the host region in developing industries that it is unable to attract and utilise advanced technology and development concepts to transform inferior industries into sectors with a comparative advantage, thereby promoting industrial structure adjustment. However, the impact mechanisms of FDI on these two dynamic processes, namely the improvement in the performance of the industrial structure and industrial structure reinforcement, are different. FDI influences both the rationalisation and strengthening of the industrial structure simultaneously through the capital supply mechanism. It affects inter-industrial structure transformation and upgrading, as well as the rationalisation of the industrial structure through an active selection mechanism and a passive competition mechanism. FDI also influences intra-industrial structure transformation and upgrading through industrial linkages, imitation and demonstration and personnel flow. These mechanisms are illustrated in .

The capital supply mechanism is the most common way FDI influences both the rationalisation and improvement of a regional or national industrial structure. According to neoclassical economic growth theory, the volume of capital influences the scale and speed of overall economic development. At the same time, the amount of capital in an industry is fundamental to economic development and is one of the most direct factors in determining the industrial landscape and its development. Generally, the main problem for a developing region is insufficient capital supply. Especially in the dynamic process of industrial structure adjustment, a significant amount of fixed asset investment is necessarily required. The capital formation effect of FDI in a region shows that foreign capital can be introduced to make up for the capital gap and liberate productivity constrained by insufficient capital (Chenery, Citation1975). The introduction of FDI can provide sufficient funds and abundant productive resources to accelerate industrial progress, establish the necessary material and infrastructural foundation for the transformation and improvement of the local or regional industrial fabric and promote industrial-economic development (Meyer & Nguyen, Citation2005; Phelps & Fuller, Citation2001; Wen, Citation2014). The capital supply mechanism encompasses both direct and indirect effects of capital. The former refers to the fact that the inflow of FDI directly increases the regional capital stock and addresses industrial development issues caused by insufficient funds (Branstetter & Feenstra, Citation2002; Wang et al., Citation2020; Zhao & Niu, Citation2013).

Modern advanced technology and marketing management experience brought by FDI can help the regional industrial landscape shift from labour-intensive to capital- and technology-intensive sectors (e.g., Kugler & Rapaport, Citation2007). The latter includes capital linkage effects and capital crowding-out effects. The entry of foreign capital requires a higher level of the development environment to match it and the host region will definitely lead to a rise in infrastructural investments and turn savings into new investments to accelerate capital formation. However, the entry of FDI will also take advantage of capital, advanced technology, new management experience and specific preferential policies to squeeze the formation of domestic capital through crowding-out effects, reducing domestic investment rates and having unfavourable impacts on the industrial structure (Aitken & Harrison, Citation1999; Fosfuri & Motta, Citation1999).

Besides the capital supply mechanism, FDI can also impact the rationalisation of the industrial structure via an active selection mechanism and passive competition mechanism. The active selection mechanism means that the host region will actively screen the inflow of FDI, including the location of FDI inflows, industries and sub-sectors and set up guiding preferential policies to promote FDI flows into specific sectors. The passive competition mechanism means that different sources of FDI investment will compete with each other in certain host regions that have a favourable investment climate. This kind of competition enables FDI investors to meet the requirements of the host region regarding industry, environment, investment barriers, etc., as much as possible. Both mechanisms would favour a rationalisation of the local industrial fabric.

Similar to the rationalisation of industrial composition, FDI can influence industrial structure upscaling through a capital effect. In addition, FDI can also affect the structural transformation and upgrading within the industry via industrial linkages, imitation and demonstration and personnel flows, all of which, in turn, affect industrial structure upgrading.

The industry linkage mechanism, within the framework of economic globalisation and division of labour in the value chain, refers to foreign enterprises utilising advanced technology and management experience as their competitive advantages. They promote the technological advancement of enterprises in the host region through forward and backward linkages, thereby driving the upgrading of the industrial structure (Blomström & Kokko, Citation1998; Fortanier et al., Citation2020; Kano et al., Citation2020; Markusen, Citation1995; Narula & Pineli, Citation2019; Pineli & Narula, Citation2023). Through the imitation and demonstration mechanism, FDI has a demonstration effect on the host country’s enterprises by adopting advanced technology or improving competitiveness. This compels local competitors to seek technological improvements, leading to the imitation of advanced practices and, consequently, an upgrade in industrial structure and productivity (Blomström, Citation1986; Jones & Wren, Citation2006; Makki & Somwaru, Citation2004; Markusen & Venables, Citation1999; Spencer, Citation2008). The personnel flow mechanism entails foreign enterprises systematically training local employees to enhance profitability. As trained talent flows into local enterprises, advanced professional technology and management concepts are introduced, resulting in improved local human capital (Gorg & Strobl, Citation2001) and generating technology spillovers (Blomström & Kokko, Citation1998; Kokko, Citation1994; Li et al., Citation2013; Merlevede & Purice, Citation2015; Wang & Chen, Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2010). This, in turn, is able to promote the upgrading of local enterprise products and technology.

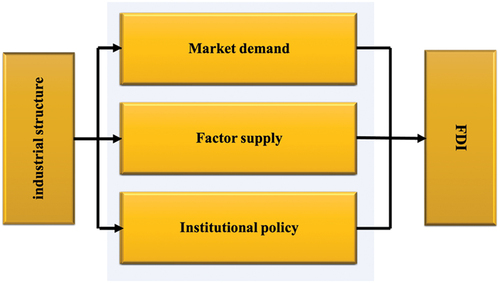

4.2. Impact mechanisms of industrial structure on FDI

Dunning’s (Citation1988) well-known eclectic theory of international production identifies three determinants of enterprises’ FDI activities: ownership advantages, internalisation advantages, and location advantages. Ownership advantage refers to the company having certain monopolistic endowments or knowledge. Internalisation advantage means that the cost of transferring ownership advantage within the enterprise is lower than transferring it outside the enterprise. Location advantage refers to the unique advantages of the host country, including preferential policies, market size, low production costs, etc. Ownership and location advantages are closely related to the industry’s absorption of FDI and the location of FDI. From the perspective of ownership advantages, factors such as industry R&D input, industry product differentiation, corporate management and marketing activities within the industry all impact the industry’s selection of FDI. From the viewpoint of location advantages, factors such as local comparative advantages, market size and preferential industry policies also impact the industry’s selection of FDI. Therefore, changes in the local industrial structure can affect the inflow of FDI through ownership and location advantages. Based on the aforementioned theories and research findings of other scholars, this article classifies the impact mechanism of industrial composition on FDI into the market demand mechanism, factor supply mechanism, and institutional policy mechanism, as shown in .

Market demand mechanism:

Changes in the industrial structure can influence FDI inflows by altering the demand structure. From the perspective of consumption demand structure, as the industrial structure changes, the consumption structure will shift from low-level to high-level outcomes, impacting the distribution of FDI inflows into industries. Industries that are popular for consumption may attract more FDI. From the perspective of investment demand structure, changes in the industrial composition will trigger shifts in fixed asset investment distribution among industries, subsequently affecting the demand for investment goods. Industries with a large market size are likely to attract more FDI. μ

Factor supply mechanism:

Different types of FDI have varying requirements for production factors. Technology-intensive FDI focuses on the quality of labor, labor-intensive FDI emphasizes labor costs, capital-intensive FDI prioritizes capital stock and resource-oriented FDI considers resource endowment in a region. When production factors are allocated among different industries, different types of FDI tend to flow into areas with appropriate factor endowments. Industries that are well integrated with local factor endowments typically attract the most FDI inflows. This indicates that changes in industrial structure can impact FDI inflows by altering the supply structure of production factors.

Institutional policy mechanism:

Firstly, changes in industrial structure prompt governments to formulate new economic policies to strengthen economic management (Hood & Young, Citation1984; Safarian, Citation1993). These policies stimulate increased foreign investment in encouraged industries, thereby promoting FDI inflows. Secondly, the upgrading of industrial structure and the emergence of new technologies lead governments to establish comprehensive policies to protect the development of new industries, which in turn affect the inflow of FDI (Huang & Zhang, Citation2020).

5. Variables, data and models

5.1. Variable selection

The simultaneous equation model (SEM) inspired by the above observations will incorporate both endogenous and exogenous variables. Each equation’s dependent variable represents an endogenous variable, while the explanatory variables can be either endogenous or exogenous. For this study, the endogenous variables encompass FDI, efficiency improvement in the industrial structure and industrial structure upgrading. On the other hand, the exogenous variables are those that can influence both FDI and the industrial structure. By considering the aforementioned analysis and existing research, the key exogenous variables are outlined as follows:

Urbanisation Rate (URB): As foreign capital enters the host region, it will face various risks, while agglomeration economies can reduce the adverse effects of these risks to a certain extent and bring specialised market services, specialised product supply and industrial information, etc. (We et al., Citation1999). All of these factors are conducive to FDI inflow. An agglomeration economy can be either a Marshall externality or a Jacobs externality, with the latter being essentially an urbanisation economy (Devereux et al., Citation2003). Therefore, the urbanisation rate can be used as a measure of an agglomeration economy. A high urbanisation level can accelerate the flow of factors, promote the accumulation of capital, technology and talent and play an important role in promoting the adjustment of the industrial structure.

Market Size (UGDP): Generally, the main goal of FDI is to open up and expand market space to obtain more profits. A large market size can reduce transaction costs and information costs and economies of scale have obvious benefits (Dunning, Citation1981; Jones & Wren, Citation2006), making it attractive to FDI (Billington, Citation1999). Market size is measured by means of urban GDP (UGDP).

Independent Research and Development Level (PAT): The higher the amount of independent research and development, the faster the technological level and innovation capability will improve, attracting more FDI (Borensztein et al., Citation1998; Buckley & Casson, Citation1976; Cantwell & Narula, Citation2003; Ford et al., Citation2008; Lim, Citation2001; Loungani & Razin, Citation2001; Van Assche & Lundan, Citation2020; Zhou et al., Citation2019). The application of new technologies can guide the evolution of traditional industries towards high-tech industries, thereby promoting productivity and the upgrading of the industrial structure (Berthélemy & Démurger, Citation2000; Hermes & Lensink, Citation2003; Loungani & Razin, Citation2001; Saggi, Citation2002; Varamini & Vu, Citation2007). The total number of regional patent applications (PAT) is used to measure the level of independent research and development.

Marketisation Level (OPEN): A high degree of marketisation means less government intervention. Foreign firms obtain normal production resources through market channels rather than other informal channels, reducing the market risks faced by FDI. The international division of labour and cooperative production can encourage the transfer of production factors to industries with a comparative advantage, thereby improving the prevailing industrial structure. This study uses the ratio of total imports and exports to regional GDP to measure the level of marketisation.

Labour Cost (WAGE): Labour cost plays an important role in FDI inflow (Mudambi, Citation1995). Low labour costs can attract a large number of labour-intensive FDI inflows. Labour cost is measured using the average wage of regional employees (WAGE).

Labour Quality (EDU): Labour quality reflects the availability of high-end talent. The higher the labour quality, the more attractive it is to knowledge and technology-intensive FDI (Villaverde & Maza, Citation2015). This article uses the number of higher education graduates to measure it.

Government Expenditure (GOV): The Chinese government has greater administrative power and executive capabilities. Government expenditure is an important determinant of local economic development. Government expenditure also reflects the government’s policy orientation, which has a certain guiding effect on the inflow of FDI. Government expenditure is measured by means of the government’s general fiscal expenditure.

Infrastructure (ROAD): Infrastructure conditions are the basic investment environment that FDI can enter (Jones & Wren, Citation2006). Complete infrastructure is an indispensable condition for reducing production and transaction costs and increasing profit returns (We et al., Citation1999). Infrastructure is measured by city road mileage per capita.

Fixed Asset Investment (FAI): Fixed asset investment is an important means of economic development. It reflects the allocation of capital factors in different industries. Capital factors often flow into industries with comparative advantages. Reasonable capital distribution drives the upscaling of the current industrial structure.

FDI: This is an endogenous variable of the simultaneous equation model, measured by the actual use of FDI in a city.

Industrial Structure Rationalisation Index (ISR): The Theil index is used as a suitable indicator to measure the rationalisation of the industrial structure. The Theil index can measure the regional income gap, taking into account the different status weights of different industries, and reflects the relationship between output value structure and employment structure. This relationship can be expressed in the following formula:

Industrial Structure Rationalisation Index (ISR): The Theil index is used as a suitable indicator to measure the rationalisation of the industrial structure. The Theil index can measure the regional income gap, taking into account the different status weights of different industries, and reflects the relationship between output value structure and employment structure. This relationship can be expressed in the following formula:

where ISR denotes the industrial structure rationalisation index; represents the value-added of the i-th industry in a certain city; GDP denotes the total value-added of the city;

indicates the share of the added value of the i-th industry in the total added value of the city;

denotes the number of employees in the i-th industry; L denotes the total number of employees in a certain city;

indicates the share of employees in the i-th industry to all employees; and ISR has a negative sign meaning: the higher its value, the less mature the industrial structure concerned is. The closer the value is to 0, the more mature the industrial structure.

Industrial structure upgrading index (ISU): Industrial structure upgrading refers to the evolution of the industrial structure system from low-level to high-level. This process involves transitioning from labour-intensive industries to knowledge- and technology-intensive ones. The upgrading of the industrial structure can be represented by the product of the proportion of output value and labour productivity:

In this formula, ISU represents industrial structure upgrading, denotes the share of value added of the i-th industry, and

represents the average labour productivity of the i-th industry. A higher proportion of industries with high labour productivity results in a larger ISU, indicating a higher degree of industrial structure upgrading in the country or region. For a detailed list of variables and their definitions, refer to .

Table 1. Definition of variables.

5.2. Data

Originally, the Pearl River Delta (PRD) encompassed nine major cities: Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Huizhou, Jiangmen and Zhaoqing. In 2017, the Guangdong Provincial Government issued the ‘Key Tasks for Promoting the Revitalization and Development of the East, West, and North of Guangdong in 2017’, expanding the PRD to include 15 cities. The additional six cities are Shaoguan, Shanwei, Yangjiang, Heyuan, Qingyuan and Yunfu. These 15 cities collectively contribute to 80% or more of the GDP and receive 95% or more of the FDI inflows in Guangdong Province, establishing the PRD as a high-density economic hub within Guangdong and a central component of the Greater Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Bay strategy. We note that, due to unavailable data, Hong Kong and Macau are not included in our empirical analyses. We sourced the data from various references, including the Guangdong Province Statistical Yearbook (Citation2006–2019), the Guangdong Province Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook (Citation2006–2019), other statistical yearbooks and statistical bulletins from the 15 cities covering different periods and the EPS database, among others. In cases where data for certain cities in specific years were missing, we applied linear interpolation to fill the gaps. A statistical description of all variables can be found in .

Table 2. Statistical description of the variables.

As shown in , the variable distribution within the PRD exhibits a satisfactory pattern that aligns with our subsequent modelling requirements. It is noteworthy that the PRD region contributes to nearly 10% of China’s GDP, while accounting for approximately 16% of its FDI. These figures have displayed a consistent level of stability in recent years.

5.3. A simultaneous equation model

The simultaneous equation model (SEM) involves the utilisation of multiple equations that are interconnected to represent a comprehensive model where economic variables within an economic system mutually depend on one another. This model captures interdependent cause-and-effect relationships. Unlike previous studies that relied on single equations to examine unidirectional relationships, which might introduce biases or errors in regression results, this article addresses potential endogeneity concerns and two-way causality by establishing an SEM. The SEM comprises three equations: one for industrial structure rationalisation, one for industrial structure upgrading and one for FDI. Through estimation, this model investigates the interactive influence relationship between FDI and industrial structure. Building upon the aforementioned theoretical framework’s logic of the interaction system between FDI and industrial structure, the SEM is represented as follows:

where ISR, ISU and FDI represent the endogenous variables for industrial structure rationalisation, industrial structure upgrading and FDI inflows, respectively; URB, PAT, UGDP, OPEN, FAI, WAGE, EDU, ROAD and GOV denote urbanisation rate, R&D level, market size, marketisation, fixed asset investment, labour cost, labour quality, infrastructure and government expenditure, respectively; and and

are the iid random disturbance terms. To reduce collinearity, heteroscedasticity and non-stationarity in the model, the variables in the model are transformed into logarithms (prefixed with ln).

The LLC test was adopted to test each variable’s stationarity for the panel data. The unit root test results are shown in , which indicates that the level value of each variable rejects the null hypothesis of the existence of a unit root, suggesting that the panel data is stable.

Table 3. LLC test for panel data.

Identifiability is a crucial prerequisite for determining the suitability of using an SEM for empirical analysis. The identification of an SEM relies on satisfying two conditions: order identification and rank identification. First, let us assume the number of endogenous variables in the SEM is denoted as ‘m’, and the number of endogenous variables in the i-th equation is . Similarly, the number of exogenous variables is represented as k and the number of exogenous variables in the i-th equation is

. To meet the requirements for first-order identification, we need

. According to the order-identification conditions, we can conclude that all three equations in the SEM model (3), namely ISR, ISU and FDI, are over-identified.

Moving on to rank identification, in a system with N equations, each equation is identified when the rank of the parameter matrix of the other variables not included in that equation is (N - 1). Following this criterion, all three equations in the SEM model satisfy the rank identification condition.

5.4. A spatial Durbin model

The Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) is a critical element of spatial effect modelling, which typically comes in two forms: a spatial lag model (SAR) and a spatial error model (SEM; Anselin, Citation1988). In the SAR model, the right side of the equation includes the spatial lag form of the dependent variable. This implies that the dependent variable is not only influenced by the unique characteristics of the region it is located in but also affected by variables from neighbouring regions. On the other hand, the SEM model incorporates spatial effects into the error term, signifying that the dependent variable is influenced by both the characteristics of its own region and those of its neighbouring regions. While the impacts from neighbouring regions remain unobserved, they are encapsulated within the error term.

When spatially-lagged explanatory variables are introduced into the spatial lag model, it transforms into a spatial Durbin model (SDM). This extension allows us to examine whether the dependent variable is directly influenced by explanatory variables within its own region as well as those in neighbouring regions. Following the approach outlined by Elhorst (Citation2014), when it is challenging to precisely determine the specific form of spatial effects, the SDM model serves as a valuable choice. Accordingly, our model is as follows:

where represents industrial structure rationalisation (ISR) or industrial structure upgrading (ISU), while FDI stands for the amount of foreign direct investment and N the number of spatial units. URB, PAT, UGDP, OPEN, FAI, WAGE, EDU, ROAD and GOV are the same variables as described in formula (3). The ‘ln’ indicates that a logarithm is applied to these variables,

and

are error terms with a mean of 0 and variances denoted as

and

; ρ, θ, α and β are parameters that will be estimated. The spatial weight matrix

is constructed using the Queen contiguity matrix. In the next section, we will present the modelling results.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. SEM model estimation results

Given that the equations in the SEM model are all over-identified, we employed the three-stage least squares estimation (3SLS) for empirical estimation purposes. The results can be found in .

Table 4. SEM model results for ISR, ISU and FDI.

In , the results show a significant positive interactive relationship between ISR, ISU and FDI. Rationalising and upgrading the regional industrial structure can attract FDI inflows and, conversely, FDI inflow can promote the rationalisation and upgrading of the industrial structure. Moreover, the urbanisation rate has a significant negative impact on the rationalisation of the industrial structure. Market size, marketisation and fixed asset investment have significant positive impacts on the rationalisation of the industrial structure. Market size and fixed asset investment also have significant positive impacts on the upgrading of the industrial structure. The urbanisation rate negatively affects FDI, while labour quality, market size, infrastructure, government expenditure and marketisation positively influence FDI. Therefore, the SEM model’s estimation results appear to support the theoretical mechanism of interaction between FDI and industrial structure, as mentioned earlier.

6.2. SDM model estimation results

When constructing a spatial panel data model, we often face the challenge of choosing between fixed effects or random effects. According to Elhorst (Citation2014), if the primary objective is to draw conditional inferences about the sample, fixed effects must be utilised. Fixed effects models are generally regarded as more suitable for spatial panel data models than random effects models. Furthermore, the Hausman test conducted here corroborates that the fixed effects model outperforms the random effects model. Consequently, the estimation results will be presented below based on the SDM fixed effects model.

Using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method, displays the results of the SDM model estimation, focusing on data from 15 cities in the PRD spanning the years 2005–2018.

Table 5. SDM model results.

In , the results indicate that R2 ranges from 0.5654 to 0.8617 for the three models, suggesting a favourable overall goodness-of-fit. In the ISR model, ln_FDI and W*ln_FDI are significant at the 10% level and ln_PAT, ln_UGDP, W*ln_UGDP and W*ln_OPEN are significant at the 1% level. This implies that the rationalisation of the industrial structure is evidently influenced by local FDI, independent R&D levels, market size and the degree of marketisation in neighbouring cities.

For the ISU model, W*ln_PAT, W*ln_UGDP and W*ln_FDI are significant at the 10% level, W*ln_URB and W*ln_OPEN are significant at a 5% level and ln_FDI, ln_PAT, ln_UGDP and ln_OPEN at the 1% level. This underscores that local FDI, independent R&D levels, urbanisation levels and factors such as market size, marketisation and fixed asset investment in neighbouring cities significantly impact the desired upgrading of the industrial composition in the PRD.

Regarding the FDI model, ln_ISR, ln_UGDP, W*ln_ISU and W*ln_ROAD are significant at the 10% level, while ln_WAGE, ln_ROAD and W*ln_GOV are significant at the 5% level. ln_ISU, W*ln_ISR,W*ln_WAGE and W*ln_OPEN are significant at the 1% level. These findings indicate that the rationalisation and subsequent upgrading of the industrial structure, labour cost, infrastructure and market size, as well as these factors in neighbouring cities, exert significant influences on FDI inflows in the PRD. However, the urbanisation level, local openness, labour quality and government expenditures do not appear to significantly affect FDI inflows (see e.g., Saini & Singhania, Citation2018; Uz Zaman et al., Citation2018). This may be attributed to the sustained high levels of urbanisation and marketisation in the PRD over the past decade, leading to foreign investment being less responsive to changes. Additionally, the PRD has attracted high-quality labour from across the country in recent decades. Consequently, the effects of infrastructure and public service systems, supported by extensive government investment, have gradually diminished and become statistically insignificant.

6.3. Total effect, direct and indirect effect: an interpretation

The total effect of each variable in the SDM model can be further broken down into its direct effect and its indirect effect. The direct effect is reflected in the local influence, while the indirect effect is the influence from adjacent areas. present the total-effects decomposition results for the ISR, ISU and FDI models.

Table 6. Total effects decomposition for the ISR and ISU models.

Table 7. Decomposition of the total effect of FDI model.

shows that, when comparing the results of the ISR and ISU models, FDI, independent R&D level, market size and marketisation all affect the rationalisation and upgrading of the industrial structure. However, the direct, indirect and total effects of each variable’s influence on the two models vary.

FDI has significant direct and indirect effects on the rationalisation of the industrial structure, with the direct effect being higher than the indirect effect. This suggests that the positive impact of local FDI on the industrial structure rationalisation in the area is greater than in neighbouring cities. This influence of FDI on industrial structure rationalisation operates through active selection and passive competition mechanisms. When FDI flows into a city, it signifies advantages in policies and resource endowments not available in neighbouring areas. FDI triggers market competition, leading to passive industry selection, which also affects neighbouring cities through the flow of products and production factors. The direct effect is usually greater because local FDI encompasses both active selection and passive competition, while the neighbouring effect mainly involves passive selection.

The impact of FDI on the upgrading of the industrial structure in the PRD region shows significant direct and total effects, with insignificant indirect effects. Foreign firms bring capital, technology, management experience and high-tech intermediate products to local firms. This knowledge transfer and skill acquisition stimulate industrial upgrading. The PRD’s convenient exchanges between local and foreign firms, technological protection and talent attraction may explain the lack of significant indirect effects.

Among other factors, independent R&D level has a significant direct effect on efficiency and industrial structure upgrading, with an insignificant indirect effect and a significantly positive total effect. A higher level of independent R&D leads to faster technological advancement and innovation capability, promoting productivity and the evolution of traditional industries towards high-tech ones.

Market size shows a significant positive direct effect and a negative indirect effect on industrial rationalisation, with a significant positive direct effect on industrial structure reinforcement. A larger market size increases consumer demand, prompting enterprises to expand and diversify their production. While it reduces transaction and information costs, it intensifies competition, encouraging product innovation and technological adoption, driving the industry towards higher levels.

Marketisation has significant positive direct and indirect effects on regional industrial rationalisation, with insignificant direct effects. Higher marketisation levels promote factors’ flow between regions, influencing industrial structure changes. The highest marketisation cities, such as Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Guangzhou, exhibit low rationalisation indices, indicating mature industrial structures. The response of rationalisation to marketisation improvement is not significant, similarly impacting the rationalisation level.

illustrates that the rationalisation and upgrading of the industrial structure significantly impact FDI inflow. Labour cost, market size, infrastructure, government expenditure, and marketisation level also influence FDI inflows.

The rationalisation and upgrading of the industrial structure exert significant direct and indirect effects on FDI. The direct effect of industrial structure rationalisation is smaller than the indirect effect, while the direct effect of industrial structure upgrading is greater. Rationalisation enhances product diversity to meet consumer demand and improves factor flow efficiency, benefitting industries with comparative advantages. Mature industrial structures attract FDI. Conversely, industrial upgrading leads to higher output value in knowledge and technology-intensive industries, making the region more attractive to knowledge-based foreign investment. The indirect effect of industrial structure rationalisation is more significant due to evolving industrial structures in other regions, while the direct effect of upgrading is greater because of significant improvements in each city’s industrial structure in the PRD.

Labour cost exhibits significant negative direct and indirect effects. Low labour costs reduce expenses for foreign enterprises, making the region more attractive to labour-intensive foreign investment. However, lower labour costs often correlate with lower labour quality. Government expenditure demonstrates significant positive direct and indirect effects. Infrastructure development supported by government investment creates an attractive ‘hardware environment’ for foreign capital inflow. Government policies such as subsidies further stimulate foreign investment. Government expenditure also reflects policy orientation and can enhance foreign investment attractiveness through joint infrastructure investment.

Marketisation displays significant positive direct and indirect effects on FDI. A higher level of marketisation reduces market risks faced by foreign enterprises, making the investment environment more appealing. Market size only shows a significant positive total effect, with no significant direct or indirect effects. A large market reduces costs for foreign enterprises, promotes economies of scale and increases profits. Infrastructure exhibits a significant positive direct effect. Robust infrastructure enhances the investment environment but has a limited impact on neighbouring cities’ investment environments.

6.4. Robustness test

This study employs two methods to assess the robustness of the model. Firstly, we replace the 0–1 contiguity matrix with an inverse distance weight matrix, derived from the Euclidean distance between city centres. Secondly, we estimate the models using all explanatory variables with a first-lagged order. The empirical findings are presented in .

Table 8. SDM regression results with an inverse distance weight matrix and first-order lagged variables.

reveals that when the 0–1 contiguity matrix is replaced by the inverse distance spatial weights matrix, some changes occur. For the ISR model, ln_URB becomes significant, while in the ISU and FDI models, no changes are observed. In the ISU model, ln_PAT becomes insignificant, whereas it remains unchanged in the ISR model. In the FDI model, ln_UGDP and ln_OPEN become significant, with minimal changes in the ISR or ISU models.

Furthermore, although the significance levels and coefficients of some variables have changed, their impact directions on the dependent variables remain consistent. In the case of first-order lagged models, ln_OPEN changes from significant to insignificant in the ISR model but remains unchanged in the ISU and FDI models. Other variables behave similarly to the traditional inverse distance weight matrix, with changes mainly in significance levels and minimal impact coefficient variations. In summary, the robustness tests suggest that our model results are stable and reliable.

7. Conclusion

Studies on FDI effects are abundant in the literature. The present paper has addressed in particular the mutually interwoven effects between FDI and regional industrial development. This topic is largely under-investigated in China, though a notable exception can be found in a thorough study by Yeung (Citation2001). The present paper has made significant operational and empirical contributions to our understanding of the interaction between FDI and regional industrial structures. The use of spatial dependence models in this context is rather unique. Our research has unfolded a comprehensive framework that sheds light on the complex spatial-economic processes underpinning FDI mobility and spatial-industrial structure adjustment (Liu & Dunford, Citation2016; Liao et al., Citation2021), revealing multiple intertwined factors mechanisms (Hsu et al., Citation2023), and effects at both local and spatial levels (Casi & Resmini, Citation2014). We offer here a comprehensive summary of our findings and their policy implications.

First, our operational framework has shed new empirical light on a multitude of mechanisms through which FDI interacts with the rationalisation and upgrading of industrial structures. These mechanisms encompass capital supply, active selection, passive competition, industrial linkages, imitation, personnel flow, market demand, factor supply and institutional policies. These insights, not completely consistent with previous similar studies (Barry, Citation1999; Hsu et al., Citation2023; Liao et al., Citation2021; Markusen & Venables, Citation1999; Wang et al., Citation2020), enhance our understanding of the complex interplay between FDI and industrial structure dynamics.

Next, empirically, our analysis of the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region has unveiled a substantial and positive interaction effect between FDI and industrial structures at the regional level. The empirical evidence demonstrates the growing importance of both effective rationalisation and the upgrading of industrial structures in attracting increased FDI inflows towards the PRD. Conversely, FDI inflows also stimulate improvements in industrial structures, which is consistent with Yeung (Citation2017). One key insight in our study underscores the critical significance of spatial effects in shaping FDI inflows and improvements in industrial structures. We found that not only do the rationalisation and upscaling of industrial structures within a specific locale significantly impact FDI inflows, but these effects also extend to neighbouring areas, which confirmed the viewpoint of Wang et al. (Citation2020). This focus on spatial dimension adds depth to our understanding of how FDI-driven changes cascade through regions.

In the third place, several key factors have emerged as influential drivers of FDI inflows and industrial structure improvements. These factors include independent research and development (R&D), market size, fixed asset investment, labour costs, government expenditure and marketisation. Importantly, we have identified that spatial effects are also at play for these factors, further emphasising the interconnectedness of regions in the context of FDI and industrial development.

Finally, turning to the policy implications of our study, we offer a set of strategic recommendations. The PRD region is ‘in full swing’ and should continue its efforts to accelerate the adjustment and enhancement of its industrial structure. This will not only attract more FDI but also stimulate economic growth, enhance the business environment and generate additional employment opportunities. Given its strategic geographic position, emphasis should be placed on expanding market size and increasing market openness in the PRD. A larger market size will diversify consumption patterns, rationalise resource allocation and attract high-end FDI focused on advanced industries. To foster independent innovation capabilities and improve labour quality in the PRD, there is a need to strengthen independent R&D efforts and attract high-level talent. This will contribute in particular to the development of high-end industries. Investment in infrastructure and increased government expenditures are of paramount importance. Government expenditure positively influences FDI attraction, while robust infrastructure reduces production and transaction costs, ultimately leading to increased profit returns.

While our study provides valuable evidence-based insights, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. Clearly, data constraints forced us to limit our analysis to the industry level, precluding a sub-sector-level examination. Additionally, we recognise the need for a more comprehensive theoretical framework in future research, based on a synthesis of location theory, industrial organisation and finance. Furthermore, our spatial Durbin model (SDM) does not fully account for all endogenous relationships, potentially introducing estimation bias. These limitations suggest many opportunities for theoretical and empirical exploration in future studies.

In summary, our research sheds light on the complex interplay between FDI and industrial structures, offering valuable insights into the multifaceted mechanisms and effects involved. The tripartite findings – positive effects of FDI on development at the regional scale, potentially positive attraction effects of regional economies on FDI and multilateral interaction effects between FDI and regional industrial structures – underscore the importance of geography in FDI analysis. As we navigate the evolving landscape of regional development, these findings serve as a foundation for informed policymaking and future research endeavours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aitken, B. J., & Harrison, A. E. (1999). Do domestic firms benefit from direct foreign investment? Evidence from Venezuela. American Economic Review, 89(3), 605–618. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.3.605

- Andreu, R., Claver, E., & Quer, D. (2017). Foreign market entry mode choice of hotel companies: Determining factors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 62(3), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.12.008

- Anselin, L. (1988). Spatial econometrics: Methods and models. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

- Aroca, P., & Maloney, W. F. (2005). Migration, trade, and foreign direct investments in Mexico. The World Bank Economic Review, 19(3), 449–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhi017

- Autant-Bernard, C., & LeSage, J. P. (2011). Quantifying knowledge spillovers using spatial econometric models. Journal of Regional Science, 51(3), 471–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2010.00705.x

- Baharumshah, A., & Almasaied, S. (2009). foreign direct investment and economic growth in Malaysia: Interactions with human capital and financial deepening. Emerging Markets Finance & Trade, 45(1), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.2753/REE1540-496X450106

- Bailey, D., Harte, G., & Sugden, R. (1994). Making transnationals accountable: A significant step for Britain. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203016664

- Barrell, R., & Pain, N. (1999). Domestic institutions, agglomerations and foreign direct investment in Europe. European Economic Review, 43(4–6), 925–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00105-6

- Barry, F. (1999), FDI and industrial structure in Ireland, Spain, Portugal and the UK: Some preliminary results. Annual Conference on the European Economy, (12).

- Beaudry, C., & Schiffauerova, A. (2009). Who’s right, Marshall or Jacobs? The localization versus urbanization debate. Research Policy, 38(2), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.11.010

- Berthélemy, J.-C., & Démurger, S. (2000). Foreign direct investment and economic growth: theory and application to China. Review of Development Economics, 4(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9361.00083

- Bhupatiraju, S. (2020). Multi-level determinants of inward FDI ownership. Journal of Quantitative Economics, 18(2), 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-019-00181-z

- Billington, N. (1999). The location of foreign direct investment: An empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 31(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.12067087

- Blomström, M. (1986). Foreign direct investment and productive efficiency: The case of Mexico. Journal of Industrial Economics, 15, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/2098609

- Blomström, M., & Kokko, A. (1998). Multinational corporations and spillovers. Journal of Economic Surveys, 12(3), 247–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00056

- Blomström, M., & Persson, H. (1983). Foreign direct investment and spillover efficiency in an underdeveloped economy: Evidence from the Mexican manufacturing industry. World Development, 11, 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(83)90016-5

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(97)00033-0

- Branstetter, L., & Feenstra, R. C. (2002). Trade and foreign direct investment in China: A political economy approach. Journal of International Economics, 58(2), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00172-6

- Braunerhjelm, P., & Svensson, R. (1996). Host country characteristics and agglomeration in foreign direct investment. Applied Economics, 28(7), 833–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368496328272

- Buckley, P., & Casson, M. C. (1976). The future of the multinational enterprise. Macmillan.

- Cantwell, J., & Narula, J. R. (2003). International business and the eclectic paradigm - developing the OLI framework. Routledge.

- Capello, R., Fratesi, U., & Resmini, L. (2011). Globalization and regional growth in Europe: Past trends and future scenarios. Springer.

- Carkovic, M., Levine, R. (2002). Does foreign direct investment accelerate growth? In T. Moran, E. Graham, & M. Blomstrom (Eds.), Does foreign direct investment promote development? (pp. 195–220). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.314924

- Casi, L., & Resmini, L. (2014). Spatial complexity and interactions in the FDI attractiveness of regions. Papers in Regional Science, 93(S1), S51–S78. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12100

- Chenery, H. B. (1975). The structuralist approach to development policy. The American Economic Review, 65(2), 310–316.

- Cheng, S. (2006). The role of labour cost in the location choices of Japanese investors in China. Papers in Regional Science, 85(1), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5957.2006.00066.x

- Cole, M. A., Elliott, R. J., & Zhang, J. (2011). Growth, foreign direct investment, and the environment: Evidence from Chinese cities. Journal of Regional Science, 51(1), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2010.00674.x

- Copeland, B. R., & Taylor, M. S. (2004). Trade, growth, and the environment. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(1), 7–71. https://doi.org/10.1257/.42.1.7

- Costantini, V., Mazzanti, M., & Montini, A. (2013). Environmental performance, innovation and spillovers. Evidence from a regional NAMEA. Ecological Economics, 89, 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.01.026

- Das, S. (2007). Externalities and technology transfer through multinational corporations: A theoretical analysis. The United Nations.

- Da Silva-Oliveira, K. D., de Miranda Kubo, E. K., Morley, M. J., & Cândido, R. M. (2021). Emerging economy inward and outward foreign direct investment: A bibliometric and thematic content analysis. Management International Review, 61(5), 643–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-021-00448-9

- David, K., Zhou, D., & Li, S. (2002). The impact of FDI on the productivity of domestic firms: The case of China. International Business Review, 11(4), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-5931(02)00020-3

- Dean, J. M., Lovely, M. E., & Wang, H. (2009). Are foreign investors attracted to weak environmental regulations? Evaluating the evidence from China. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.11.007

- Devereux, M. P., Griffith, R., & Simpson, H. (2003), Agglomeration, regional grants and firm location, the institute for fiscal studies. Working Paper WP04/06, The Institute of Fiscal Studies, London.

- Dunning, J. H. (1981). International production and the multinational enterprise. George Allen & Unwin.

- Dunning, J. H. (1988). The theory of international production. The International Trade Journal, 3(1), 21–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853908808523656

- Dunning, J. H. (2001). The eclectic (OLI) paradigm of international production: Past, present and future. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 8(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13571510110051441

- Dunning, J. H., Kim, Z. K., & Lee, C.-I. (2007). Restructuring the regional distribution of FDI: The case of Japanese and US FDI. Japan & the World Economy, 19(1), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2005.07.003

- Elhorst, J. P. (2014). Spatial econometrics from cross-sectional data to spatial panels. Springer.

- Federici, D., & Giannetti, M. (2010). Temporary migration and foreign direct investments. Open Economies Review, 21(2), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-008-9092-6

- Feldman, M. P., & Audretsch, D. B. (1999). Innovation in cities: science-based diversity, specialization and localized competition. European Economic Review, 43(2), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00047-6

- Ford, T., Rork, J., & Elmslie, B. (2008). Foreign direct investment, economic growth, and the human capital threshold: Evidence from US States. Review of International Economics, 16(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2007.00726.x

- Fortanier, F., Miao, G., Kolk, A., & Pisani, N. (2020). Accounting for firm heterogeneity in global value chains. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(3), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00282-0

- Forte, R., & Moura, R. (2013). The effects of foreign direct investment on the Host country’s economic growth: Theory and empirical evidence. The Singapore Economic Review, 58(3). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590813500173

- Fosfuri, A., & Motta, M. (1999). Multinationals without advantages. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 101(4), 617–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9442.00176

- Gheasi, M., Nijkamp, P., & Rietveld, P. (2013). Migration and foreign direct investment: Education matters. The Annals of Regional Science, 51(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-012-0533-1

- Glaeser, E. L., Kallal, H. D., Scheinkman, J. A., & Shleifer, A. (1992). Growth in cities. Journal of Political Economy, 100(6), 1126. https://doi.org/10.1086/261856

- Gorg, H., & Strobl, E. (2001). Multinational companies and productivity spillovers: A meta-analysis. The Economic Journal, 111(475), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00669

- Grilli, V., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. (1995). Economic effects and structural determinants of capital controls. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, 42(3), 517–551. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867531

- Grimes, S., & Yang, C. (2018). From foreign technology dependence towards greater innovation autonomy: China’s integration into the information and communications technology (ICT) global value chain (GVC). Area Development and Policy, 3(1), 132–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2017.1305870

- Guangdong Provincial Bureau of Statistics. (2006-2019). Guangdong province science and technology statistical yearbook. China Statistics Press.

- Gunby, P., Jin, Y., & Reed, W. R. (2016). Did FSI really cause Chinese economic growth? A meta-analysis. World Development, 90(C), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.001

- Haddad, M., & Harrison, A. (1993). Are there positive spillovers from direct foreign investment? Evidence from panel data for Morocco. Journal of Development Economics, 42(1), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(93)90072-U

- Head, K., Ries, J., & Swenson, D. (1995). Agglomeration benefits and location choice: Evidence from Japanese manufacturing investments in the United States. Journal of International Economics, 38(3–4), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1996(94)01351-R

- Hermes, N., & Lensink, R. (2003). Foreign direct investment, financial development and economic growth. Journal of Development Studies, 40(1), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293707

- He, J., & Wang, H. (2012). Economic structure, development policy and environmental quality: An empirical analysis of environmental Kuznets curves with Chinese municipal data. Ecological Economy, 76, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.01.014

- Hood, N., & Young, S. (1984). Industry, policy and the Scottish economy. University Press, Edinburgh.

- Hsu, W., Lu, Y., Luo, X., & Zhu, L. (2023). Foreign direct investment and industrial agglomeration: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 51(2), 610–639.

- Huang, H., & Wei, Y. (2014). Intra-metropolitan location of foreign direct investment in Wuhan, China: Institution, urban structure, and accessibility. Applied Geography, 47, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.11.012

- Huang, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2020). The innovation spillovers from outward and inward foreign direct investment: A firm-level spatial analysis. Spatial Economic Analysis, 15(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2019.1618484

- Hunya, G. (2002). Restructuring through FDI in Romanian manufacturing. Economic Systems, 26(4), 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0939-3625(02)00063-8

- Javorcik, B. (2004). Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. American Economic Review, 94(3), 605–627. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041464605

- Jones, J., & Wren, C. (2006). Foreign direct investment and the regional economy. Ashgate.

- Kang, Y., & Annd Jiang, F. (2012). FDI location choice of Chinese multinationals in East and Southeast Asia: Traditional economic factors and institutional perspective. Journal of World Business, 47(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.10.019

- Kano, L., Tsang, E. W., & Yeung, H. W. C. (2020). Global value chains: A review of the multi-disciplinary literature. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(4), 577–622. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00304-2

- Kokko, A. (1994). Technology, market characteristics, and spillovers. Journal of Development Economics, 43(2), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(94)90008-6

- Krugman, P. R. (1991). Geography and trade. MIT Press.

- Krugman, P. (2015). Interregional and international trade: Different causes, different trends? In P. Nijkamp, A. Rose, & K. Kourtit (Eds.), Regional science matters: studies dedicated to Walter Isard (pp. 27–34). Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07305-7_3

- Kugler, M., & Rapaport, H. (2007). International labor and capital flows: Complements or substitutes? Journal of Economic Letters, 94, 15–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2006.06.023

- Latorre, M. C., Yonezawa, H., & Zhou, J. (2018). A general equilibrium analysis of FDI growth in Chinese services sectors. China Economic Review, 47(1), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.09.002

- Lee, M., & Tcha, M. (2004). The color of money: The effects of foreign direct investment on economic growth in transition economies. Review of World Economics, 140(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02663646