ABSTRACT

In this article, I read Hilgard Hall as a text of whiteness to explore how one campus building at the University of California, Berkeley renders racial power relations in the academy. Through the lens of critical whiteness studies, I examine Hilgard Hall’s namesake, architecture features, and weighty epigraph, to rescue for human society the native values of rural life. Specifically, I analyse Hilgard Hall’s identity as a building dedicated to agricultural research and education through its entanglement with Berkeley’s history as a land-grant institution. I offer a possible vision for Hilgard Hall that attempts to enable the building to become a ‘spatial race traitor’ through renovation and occupation. This article speaks to the current debates on removing monuments and building names and how agricultural programmes might approach addressing the ways white supremacy is literally constructed in(to) their teaching and research spaces.

Introduction

In ‘Breaking the Chains and Steering the Ship’ Lipsitz (Citation2008) describes approaching the Butler Library at Columbia University and noticing the names of Greek and Roman scholars engraved on a friezeFootnote1 above a colonnade. He writes: ‘the wall above the entrance to the Butler Library marked that building as a particular kind of a space, as a place where those who enter are invited to think of themselves as the heirs to only one lineage. The frieze proclaims that Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Cicero, Virgil, and their literal or figurative descendants are welcomed here. But what about everyone else?’ (89). While such literary gods of Western thought might be expected to crown one of the lofty Ivy Leagues, across the country at the University of California, BerkeleyFootnote2 – the most elite of the ‘public’ universities in the United States – Hilgard Hall replies with a colonnade and inscribed frieze of its own: To rescue for human society the native values of rural life. The conversation between Butler Library and Hilgard Hall reveals how white hegemony is literally carved into the stone faces of American universities.

How do buildings speak, and what might we do when their discourse is racist? The debate over the removal of monuments and building names has become a zeitgeist of the post2020 so-called ‘racial reckoning’ in the U.S., and since its inception in 2013 the Black Lives Matter movement has brought vital attention to the intersections of race and memorialisation, including on university campuses (e.g. Gebrial Citation2018; Jampol Citation2020; Leyh Citation2020; Evans and Lees Citation2021). UC Berkeley unnamed five buildings between November 2020 and February 2023 (University of California, Berkeley Citationn.d.). In this article, I read Hilgard Hall as text of whiteness to explore how one campus building renders racial power relations in the academy. Specifically, I analyse Hilgard Hall’s identity as a building dedicated to agricultural research and education through its entanglement with Berkeley’s history as a land-grant institution. I then offer a possible vision for Hilgard Hall, which attempts to enable the building to become a ‘spatial race traitor’ (after Ignatiev and Garvey Citation1996) through renovation and occupation.

Whiteness and land-grant agricultural education

A field of inquiry that coalesced in the 1990s but traces its roots to W.E.B. Du Bois’ pioneering work of the early 20th century, critical whiteness studies is a framework within critical race theory that focuses on whiteness in order to critique and transform it (Twine and Gallagher Citation2008; Leonardo Citation2013). Critical whiteness studies understands white supremacy to be at the structural core of racism, while turning the attention to making ‘whiteness visible, in order to disrupt white dominated systems of power’ (Applebaum Citation2016, 2). Here, I apply critical whiteness studies at the intersection of agricultural education and architecture, to reveal how whiteness as an ideology permeates both pedagogy and place.

Situated on the northwest side of the Berkeley campus, Hilgard Hall houses laboratories, offices, and classrooms for the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM). Hilgard Hall, together with neighbouring Wellman and Giannini Halls, form the three-building Agricultural Complex within the Rausser College of Natural Resources, the entity within UC Berkeley that upholds the University’s historic land-grant mission.Footnote3 Hilgard Hall’s status as an agricultural research building is key to understanding its specific material and epistemological implication with whiteness. The University of California was founded as a result of the Morrill Act of 1862, which established agricultural and mechanical arts colleges by granting public lands to states to promote the ‘liberal and practical education of the industrial classes’ (National Archives and Records Administration Citation1862). The land-grant university movement brought liberal ideals to (white, male, Christian) Americans by reducing class barriers to education, while also serving settler colonial interests by funding universities via the sale of Indigenous lands and institutionalising white supremacy through European agricultural knowledge production (paperson Citation2017; Stein Citation2017; Nash Citation2019; Lee and Ahtone Citation2020). U.S. public higher education has always already been entwined with whiteness as property (Harris Citation1993): the land-grant universities, including UC Berkeley, continue to draw interest from the original financial endowments garnered through theft of Indigenous lands (Lee and Ahtone Citation2020).Footnote4 By ‘equalising’ educational opportunities, the Morrill Act promoted a shared white identity among poorer citizens and recent European immigrants (Roediger Citation2007) through their contrast with Indigenous Others – whose land was appropriated –and Black Others – who were de jure barred from southern land-grant universities and de facto excluded from those in the rest of the U.S.Footnote5 Agricultural education, in particular, provided recent white arrivals to California with the tools through which to occupy land and cultivate a white culture (cf. Mayes Citation2018).

Eugene Woldemar Hilgard

From 1875 to 1906, UC Berkeley’s agricultural education functioned under the directorship of Eugene Woldemar Hilgard, a German-born, Illinois-raised, German-educated geologist, chemist, and botanist who was one of the leading founders of modern soil science. Hilgard was recruited to Berkeley in 1875 to address an ontological tension in the University’s early years between its simultaneous development as a school of classical studies fashioned after the elite colleges of the northeast, and as a vocational farming school. Due to ambiguity in the language of the Morrill Act, states interpreted the legislation to develop a variety of educational models. Some designed programmes in manual instruction to graduate practicing farmers, whereas others used the Morrill Act funding to create or expand schools (often those already offering elite education) that focused on advancing scientific curricula for technical and managerial agricultural careers (Sorber and Geiger Citation2014). The University of California had been founded in 1868 by combining the fifteen-year-old private liberal arts College of California with a new Morrill Act-funded Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College that had been formally established by the California legislature in 1866 but was yet to function (Stadtman Citation1970). In its first decade, the University of California was fraught with political turmoil over its competing missions. The populist Patrons of Husbandry, also known as the Grangers, fought for the University’s College of Agriculture to directly serve farmers through practical education, whereas the regents prioritised the classical and scientific arts taught in the College of Letters (Slate Citation1919; Stadtman Citation1970). Hilgard helped bridge a gap between those who saw the study of farming and philosophy as incompatible: his progressive approach to agricultural education as a positivist research endeavour was highly influential in shaping the discourse of agriculture as a ‘science’ above a practice, yet he also committed to making this new scientific learning accessible to farmers via public lectures and short courses (Slate Citation1919). Hilgard expanded the University’s agricultural education beyond the central Berkeley campus by setting up one of the first U.S. Agricultural Experiment Stations, a series of research plots throughout California designed to bring agricultural science to new settler farmers up and down the state. Hilgard’s work on soils and a wide array of crops had a profound effect on the institutionalisation and success of white settler agriculture in California as well as across the U.S. through the dissemination of his writings.

Prior to joining the faculty at the University of California, Hilgard spent one year at the University of Michigan, preceded by a dual appointment as the Mississippi State Geologist and professor at the University of Mississippi from 1855 to 1873. During the Civil War, Hilgard sided with the Confederacy and subsequently refused to take the Union oath (Rose and Nathanail Citation2000). While he resisted conscription into an official position in the Confederate army (Hilgard Citation1863) he served as caretaker of the University of Mississippi grounds for the length of the war and performed operations for the Confederacy ranging from processing nitrate and salts to building floodlights for battle to nursing wounded soldiers (Hilgard Citationn.d.). In his unpublished memoir, Hilgard speaks of his racial-political views as such:

As for myself, while I opposed secession and considered the Confederate constitution a mere rope of sand fatally weak in its very origin from the extreme states-rights doctrine, I determined that, as the legislature had actually, while suspending the Geol[ogic] Survey ‘during the war and for one year thereafter’, provided the continuance of my salary at the rate of $1,500 during the war, making it my duty to care for the collections of the survey and to ‘do such work as the Governor of the state might direct’, I considered it but decent to stay and share the fate of the South, however little I believed in its final success. I did this the more willingly as I had personally become aware of the gross exaggeration of the cruelties toward the slaves alleged by the abolitionists of the North to be of common occurrence, and of the inability of the negroes to become anything but a service race, even if set free (Hilgard Citationn.d.).

Hilgard wrote to his brother Julius in 1865, of the anti-slavery Radical Republicans: ‘What a devil of rumpus the Radicals are kicking up at Washington! … They must be stark raving mad up yonder’ (Hilgard Citation1865), and criticised efforts during Reconstruction to admit African American students to the University of Mississippi. He explains of his decision to move his family to Michigan in 1873: ‘I had become somewhat tired of the prospect of having my children grow up under the harrassing (sic) black shadow of negro domination’ (Hilgard Citationn.d., 59). After his arrival in Berkeley, Hilgard became close personal friends with Social Darwinists John and Joseph LeConte, professors and brothers from a slave-owning family who had also left the South due to their disagreement with social changes regarding Black rights during Reconstruction (Hilgard Citation1907).Footnote6

Hilgard’s remarks on Native Americans, whom he surely interacted with during his extensive fieldwork as part of the work of the Agricultural Experiment Stations, do not contain the same blatant racism as his writings on African Americans.Footnote7 In his memoir, he notes passing through the Yakima Indian Reservation in Washington State in 1881 as part of the Transcontinental Geologic Survey, but makes no further comment (Hilgard Citationn.d.). It should be noted that Hilgard wrote in praise of Native American soil conservation practices, such as cultural burning, as superior to those of white American settlers. While the entirety of his career was dedicated to providing whites with scientific knowledge to succeed in settler agriculture, he wrote, perhaps with irony:

Armed with better implements of tillage it takes [us] but a short time to ‘tire’ the soil first taken into cultivation … If we do not use the heritage more rationally, well might the Chickasaws and the Choctaws question the moral right of the act by which their beautiful parklike hunting grounds were turned over to another race, on the plea that they did not put them to the uses for which the Creator intended them … Under their system these lands would have lasted forever; under ours, as heretofore practiced, in less than a century more the State would be reduced to the condition of the Roman Campagna’ (quoted in Jenny Citation1961, 9–10, emphasis in original).

He also published in praise of Chinese and Japanese farmers’ use of night soil (human manure) in maintaining fertility of crop lands and criticised American sewage systems for sending nutrients out to sea (Jenny Citation1961). Thus, while Hilgard openly expressed anti-Black racism, his views of Native Americans and East Asians – or, at minimum, his view of their methods for promoting soil health – were more positive.Footnote8

Approaching Hilgard Hall

Hilgard Hall was completed in 1917, a year after Eugene Hilgard’s death. The timing of the building’s construction is significant in terms of Progressive Era architectural expressions of whiteness, and, as explored in the next section, the corresponding agricultural articulations of whiteness its epigraph embodies. If Hilgard Hall’s appellation pays honours to a man responsible for the proliferation of settler agriculture through white scientific thought and who openly expressed anti-Black racism, the building’s architecture speaks to whiteness as an ideology that pervaded Berkeley’s early campus master plan. Hilgard Hall was designed by John Galen Howard, UC Berkeley’s first supervising architect and the founder of the School of Architecture. Howard designed all the permanent campus buildings between 1903 and 1926 in the Beaux-Arts style, including such iconic landmarks as Wheeler Hall, Sather Gate, and Memorial Stadium. In 1982, Hilgard Hall was among 11 of Howard’s designs added to the National Register of Historic Places (Knapp Architects Citation2012). Hilgard Hall is thus one sibling in a white brotherhood of state-honoured buildings.

Howard was trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where the style so integral to the American City Beautiful movement was developed. The movement, which made its debut at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, was a Progressive Era paternalistic approach to architecture and urban planning that explicitly aimed to ‘uplift’ lower classes through social control via the built environment. As a response to what its founders saw as the squalor of American cities resulting from industrialisation and the influx of Southern and Eastern European immigrants, City Beautiful attempted to impel white American identity formation out of European ethnic ‘inbetweens’ (Barrett and Roediger Citation1997). The utopian model city on display at the World’s Columbian Exposition was even called ‘the White City’. While this ostensibly referred to the colour of the buildings, Huhndorf (Citation2001) notes that as a ‘heavily laden symbol and an obvious tribute to racial whiteness, the aptly named White City provided the centrepiece of the event, and, by implication, the nation’s narrative as well’ (40). With its procession of grandiose pale buildings, open spaces, and long axes, the master plan for the UC Berkeley campus created by Emile Bernard and John Galen Howard reflects the design principles of the City Beautiful movement, with a particularly Californian imperial embellishment: the red clay tile roofs crowning the majority of Howard’s buildings evoke a Spanish imaginary that pays homage to the first white colonisers in California (Young Citation2006).

In the first decade of the 1900s the City of Berkeley was quickly becoming an urban centre. It was the fourth fastest-growing city in the U.S. (Wollenberg Citation2008). Berkeley’s metropolitan development, and the University in particular, were thoroughly intertwined with rural life. As noted above, Eugene W. Hilgard had a significant influence on the burgeoning rural white American (agri)cultural identity throughout the state. Knowledge produced in the material spaces of City Beautiful buildings created what we might call a ‘Rural Beautiful’ Progressive Era influence on agrarian communities.Footnote9 Simultaneously, romantic representations of rural European farm life were physically imprinted on urban edifices. The UC Berkeley Agricultural Complex references the design of a Tuscan farm (Hodgson Citation1917). Hilgard Hall in particular has been described as of ‘a Florentine Renaissance style’ (United States Department of the Interior and Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service Citation1982). It is shaped like an elongated ‘C’ and its exterior is a tapestry of washed-out grey, creamy white, light pink, and pale yellow. The building’s façade is covered with sgraffitoFootnote10 panels and cornices representing agricultural crops and domesticated animals, interspersed with winged cherubs. Of note, every single crop is European in origin. In particular, chaffs of wheatFootnote11 and European-style sickles adorn Hilgard Hall’s many corners and entryways, lest you forget that white foodways, white technology (and the blessings of white angels) dominate here (). Hilgard Hall’s only nod to local or endemic species is the inclusion of stylised California poppies, the State flower (which is used in Indigenous medicine). As a visual celebration of the intellectual endeavours that occur inside the building, whiteness remains an unmarked marker, operating ‘as the normative cultural centre’ (Twine and Gallagher Citation2008, 9), when in fact referencing Europe in particular. Hilgard Hall’s front entry is a set of enormous double doors of panelled, tightly woven iron lattice, situated between ten towering white columns. Sleeter (Citation1993) remarks that ‘[s]chools are one of the main gatekeepers in the allocation of social resources’ (171). While Sleeter’s use of ‘gatekeeper’ is metaphorical, in the case of Hilgard Hall, the doors quite literally serve this function: they are so physically heavy that I personally can barely push them open (). Furthermore, to approach Hilgard Hall’s main entrance, one must ascend a hill. My mind cannot help but turn the building’s name into ‘Hill Guard’.

Inscribing whiteness

Above the imposing doors we arrive at Hilgard Hall’s epigraph: To rescue for human society the native values of rural life. This peculiar phrase was written by Benjamin Ide Wheeler, who was the president of the University of California from 1899 to 1919 (Taylor Citation1945).Footnote12 Through the lens of critical whiteness studies, this short sentence speaks volumes and merits a phrase-by-phrase analysis. Like the sgraffito technique used on Hilgard Hall’s epidermis, we can scratch beneath the surface of the epigraph to hear whiteness speak its name (Lipsitz Citation2018). Without identifying a subject, the root verb to rescue interpellates whites. Domination disguised as saviorism is a classic imperialist move, predicated on the Racial Contract (Mills Citation1997), or set of formal and informal agreements among whites to advantage themselves as a group through domination and exploitation of nonwhites. In naming the reality of the Racial Contract, Mills elucidates that ‘society’ is not made up of free and equal individuals, as European humanism declares, but rather is a divided between white people and racialised subpersons. To rescue is ‘the white man’s burden’ (Kipling Citation1899), and fits the settler-colonial context of Manifest Destiny in which the original Morrill Act was passed. Mills (Citation1997) elaborates that the Racial Contract necessitates ‘the development of a depersonizing conceptual apparatus through which whites must learn to see nonwhites and also, crucially, through which nonwhites must learn to see themselves’ (87–88). To this end, the notorious Indian boarding schools of the late 1800s/early 1990s sought Christian cultural assimilation: Native Californians were ‘rescued’ through removal and ‘education’—what Leonardo (Citation2015) calls ‘eraducation’—and the land was ‘rescued’ for white agricultural settlement. Three of the 25 Indian boarding schools were in California (Gerencser, Rose, and Triller Doran Citationn.d.), and one, the Sherman Indian School, opened its doors in Riverside in 1902 (Trafzer, Allen Smith, and Sisquoc Citation2017), just five years before the establishment of the University of California Citrus Experiment Station less than ten miles away (University of California, Riverside Citationn.d.).Footnote13

In the phrase for human society, ‘human’ again prefigures white. Mills (Citation1997) explains that the Racial Contract dictates that ‘the creation of society requires the intervention of white men, who are thereby positioned as already sociopolitical beings’ (13, emphasis in original), as compared to racialised subhuman Others. Yet the specificity of whiteness is disguised in the non-raced language of universalism (Leonardo Citation2004). Native values rings with irony, given the University’s origin story through the sale of unceded Indigenous land. The architectural drawings for Hilgard Hall were completed in 1916, the same year as the death of Ishi, a Yana man who was infamously kept as a University of California anthropology exhibit. Continuing with the Racial Contract framework, native values might be interpreted as the ‘original’ or ‘innate’ nature of white men, who are the only real humans capable of a moral, social life. The contractarian tradition posits that men agree to leave ‘the state of nature’ to form society, and perhaps the Rousseauan version of the social contract best explains the emphasis placed on the superior value of a specifically rural life. A romantic idealisation of rural life emerges from Rousseau’s contradictory writings that on one hand apotheosised ‘natural man’ as akin to some sort of pre-civilised ‘savage’ (he is careful to make racialised distinctions between Native American ‘savages’ and European savagery of some ‘dim distant past’ [Mills Citation1997, 68]) while on the other hand claiming the necessity of men to form society in order to become full moral agents (Rousseau Citation2007).

It merits a discussion of rural society during California’s early statehood to further unpack the ideology of whiteness written between the lines of Hilgard Hall’s epigraph. California’s particular settler-coloniality resulted in social institutions that differed from the agrarian culture of small-to-medium family-run farms that were more typical in the U.S. and idealised in the national imaginary as the Jeffersonian ‘yeoman farmer’. Following the Conquest of California in 1846, during the early American era (the era of genocide of Native Californians), land use policy was driven by enormous speculative holdings and quick-cash desires of gold mining. The sheer scale of individual parcels followed the pattern of privately owned cattle and sheep ranchos created during the Mexican era (1821–1846), which, in turn, were carved out of the vast land grabs by the Catholic church under the Spanish crown between 1769 and 1821. Yeoman agriculture – that is, a society of white men who owned their land and worked it with family labour – was the dominant structure, and ideal, of early American agriculture, but in California agriculture began with agrarian capitalism (Walker Citation2004). California’s large landholders were (and are) commonly called ‘growers’ rather than ‘farmers’, more analogous with the southern ‘planters’ than the ‘family farmer’. In fact, California’s early agriculture resembled (and does to this day) southern plantations, as large cash crop agriculture is structurally designed to function through exploitation of cheap or slave labour. Similar to the enslavement of Africans and their descendants on plantations in the southern U.S., the Spanish missions operated through enslavement of Native Californians. While California entered the union as a free state, in part because white miners were loath to have their labour reduced in value by the presence of Blacks (Taylor Citation1945; Almaguer Citation2009), the large landholders were enthusiastic to exploit the cheap labour of Chinese immigrants on their cash crop, monocultural operations.

What does this have to do with ‘the native values of rural life’ so in need of rescuing in the early 1900s? Taylor (Citation1945) suggests that Hilgard Hall’s epigraph specifically refers to the debate in the 1850s–1890s between two different visions of California agriculture, albeit a cut within white racialised subjecthood: one held by the capitalist operators asserting their right to underpay Chinese labourers, and the other held by smaller-scale farmers arguing for the greater worth of their own labour and social standing as independent yeoman. The latter won this particular war of position (cf. Gramsci Citation1971), contributing to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Almaguer (Citation2009) adds: ‘Anti-Chinese sentiment in rural California developed, as it did elsewhere in the state, against the backdrop of an emergent class conflict within the white population between white capitalist interests and white immigrants, who were increasingly being proletarianised and placed into competition with non-white labour’ (170). While one must be careful not to conflate the lives of white wage labourers with land-owning small-scale farmers, Roediger’s (Citation2007) argument on the simultaneous development of white and working class identity formation is useful here, particularly with the Morrill Act’s emphasis on education for the ‘industrial classes’.

Alvarado (Citation2019) offers the useful term ‘settler rurality’ to describe the process that produced race in California’s agricultural spaces through ‘the ideological and material reordering of the land along U.S. settler colonial paradigms’ (17). Both the large capitalist growers and yeoman farmers obtained land in California in the first place through their racialised position as whites. Land acquisition through the Morrill Act, Homestead Act, and Railroad Act (what elsewhere [Fanshel Citation2021] I call the ‘Settler Colonial Acts of 1862’) was predicated on denial of Native Californian subjecthood, per the Racial Contract. Furthermore, Blacks were de facto barred from obtaining land under the Settler Colonial Acts. For example, only 0.2% of the approximately 270,000,000 million acres granted through the Homestead Act went to African Americans (National Park Service Citation2019, Citation2021). If property is a bundle of rights, then access to each individual right is thoroughly mediated through whiteness: the right to be recognised by laws; purchase land; use the land one has purchased; exclude others from that land; and importantly, to have a voice in the political process (Harris Citation1993). Since the beginning of the American colonial era, largescale agribusiness and yeoman farming have been competing visions of California’s agricultural society, with both racial formation (Omi and Winant Citation2015) and the University of California squarely at the centre of the debate.

At the time of Hilgard Hall’s construction, land redistribution via the Homestead Act was at its peak (National Park Service Citation2019), and the populist Grangers, which represented the interests of yeoman farmers, had a strong influence on the direction of the University of California’s agricultural education (Hilgard Citationn.d. Slate Citation1919; Alvarado Citation2019). Alvarado traces the prominent role of Elwood Mead, a professor of rural institutions who joined the College of Agriculture in 1911, in promoting a vision of white settler rurality that favoured the California Grange’s constituents over the large landholders. Mead was a key figure in creating two state-run agricultural colonies in the Central Valley, Durham and Delhi, that aimed at ensuring the success of white settlers. Writing in 1920, Mead et al. described the agricultural colonies as a project in a rural white identity formation:

The thirteen nationalities at Durham include some people who would, if left to themselves, join racial groups, but who at Durham are among the most active in creating the social fabric needed in the rural life of California … and more Durhams and Delhis there are, the more certain it is that rural California will be in the next half century remain the frontier of the white man’s world (quoted in Alvarado Citation2019, 49).

In Mead’s vision of white settler rurality, we also see a rearticulation of the debate between liberal scientific and vocational education that had brought Eugene W. Hilgard to Berkeley in the 1870s. Nationally, this tension was addressed in 1914 with the passage of the Smith Lever Act, which formally created the Cooperative Extension Service to serve rural populations through practical applications of university research (Sorber and Geiger Citation2014). Hayden-Smith and Surls (Citation2014) state that ‘the Smith-Lever Act was rooted in the Progressive philosophy of helping people help themselves’ (10). Farm advisors and home demonstration agents were deployed throughout the state to teach white families gendered skills for settler life: men were taught about local soil, weather, and crop conditions, women learned food preservation and nutrition, and through new 4-H youth development clubs farm children were indoctrinated with the skills and ethos for the continuation of rural communities. In penning the epigraph on Hilgard Hall in 1917, President Wheeler confirmed the University’s contemporaneous sentiment on the work of the College of Agriculture. Wheeler said: ‘Our business ultimately is a sociological business. Considerations of soil technology but scratch the surface. What we are busied with here is trying to find out how to adjust the soil to the uses of families’ (quoted in Taylor Citation1945, 193). UC Berkeley’s land-grant education was ready to heed the call, answering to its interpellation as ‘rescuer’.

Inside Hilgard Hall

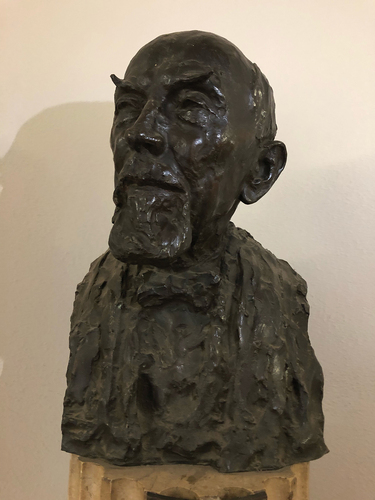

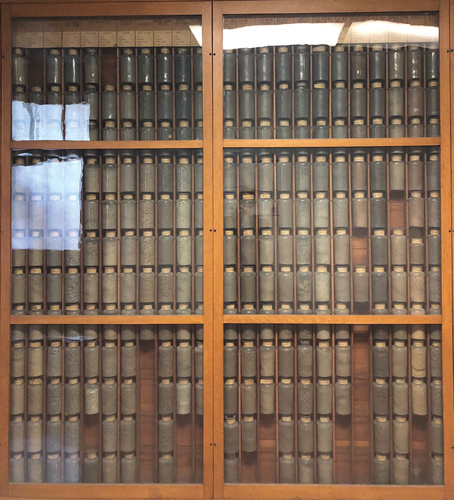

A bronze bust of Eugene Hilgard is prominently located near the main first-floor entryway (), and cases contain his photographic portrait, laboratory equipment, and other memorabilia. The hallways of three floors are lined with cabinets filled with hundreds of jars of California soil samples that Hilgard collected (). It’s important to remember that UC Berkeley was founded through the selling of 150,000 acres of unceded Indigenous land from over 70 tribes across the territory that is now called California (Lee Citation2020). First, the federal government claimed this land as theirs to sell, and then white speculators rushed to buy it. Hilgard Hall’s visual display of the physical material of the land contained and classified for academics to mix with their academic labour, literally locked up to be made ‘real’ in the Lockean (Citation1978) sense, is further evidence of whiteness as a form of property (Harris Citation1993). In contrast to the worldview of western materialist science, from the perspective of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, people ‘inhabit a landscape of gifts peopled by nonhuman relatives, the sovereign beings who sustain us’ (Kimmerer Citation2018, 27). Hilgard Hall’s century-long display of captured soil is a visual reminder that settler-colonialism is a structure, not an event (Wolfe Citation2006).

If white men are overprivileged in the content of curriculum (McIntosh Citation2004) they are also excessively privileged as the people who have made the ranks to deliver the curriculum. For example, 38 out 55 of ESPM’s current ladder rank faculty are white and 38 are male (Univeristy of California, Berkeley Citation2022).Footnote14 This disproportionate advantage is on display on a crusty bulletin board of photographs of ESPM’s Division of Ecosystems Sciences faculty on Hilgard Hall’s first floor. The placard has several blank slots, where photos appear to have been removed or fallen off. These ‘missing faculty’ might represent the faculty of colour who never were ().

Racetalk: immunity and terror

The architectural and other material features of Hilgard Hall narrate racial domination, articulating in stone, concrete, and iron the terms of UC Berkeley’s agricultural education. Hebdige (1979) says:

The buildings literally reproduce in concrete terms prevailing (ideological) notions about what education is and it is through this process that the educational structure, which can, of course, be altered, is placed beyond question and appears to us as a “given’” (i.e. as immutable). In this case, the frames of our thinking have been translated into actual bricks and mortar (13)

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the extent to which UC Berkeley agricultural research space is raced and race is spaced (Lipsitz Citation2007) was revealed anew. When campus buildings were shuttered in 2020 to all but those who had received research exemptions, there were incidents of Black and Brown graduate students in the Rausser College of Natural Resources attempting to access their laboratories only to be stopped by the UC Police Department and asked for clearance papers. One Black student told me:

A friend was like, “Did you get your freedom papers?” And I was like … that’s a good word for it. Because that explains why I was so uncomfortable having this piece of paper to show to cops if anyone ever said, “Are you supposed to be here?” I’d be like, “Um, yes, yes, let me just prove to you that I’m supposed to be here” (Personal communication, 30 October 2020).

Mills (Citation2007) speaks of how the social memory of monuments contributes to white ignorance. Hilgard Hall’s epigraph and other visual representations of white settler conquest and European agricultural knowledge production are a ‘mystification of the past [that] underwrites a mystification of the present’ (31). As UC Berkeley students, faculty, and staff go about their daily educational and research activities, buildings like Hilgard Hall create a spatial habitus (Bourdieu Citation1977) that valorises white territorial and epistemological dominance and normalises exclusion of, and violence towards, bodies and knowledges of colour. This contributes to ‘white cognitive distortions’ (Mills Citation2007, 35) for white people, who have the immunity not to question the cultural reproduction of these spaces, and racial gaslighting (Davis and Ernst Citation2019) for people of colour, whose very navigation of the same buildings can be an act of resistance.

Renovations and occupations

If whiteness is ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ (Roediger Citation1994, 13, emphasis in original) what to do about Hilgard Hall? The debate between the abolition versus reconstruction of whiteness (see for example Ignatiev and Garvey Citation1996; Giroux Citation1997) can be extended to material sites that reproduce white supremacy. Eugene W. Hilgard’s personal racial views align with the architectural and agricultural ideologies of white domination that undergird the eponymous building’s physical features. Should Hilgard Hall be demolished, unnamed, or at the very least its epigraph chiselled away? During the summer 2020 protests following the murder of George Floyd, activists and municipalities alike rushed to remove monuments of white supremacists, and a renewed public conversation has flourished on the topic. While I personally agree with removing statues of Robert E. Lee and Junipero Serra and the unnaming UC Berkeley’s Boalt, Barrows, LeConte, Kroeber, and Moses Halls (University of California, Berkeley Citationn.d.), there’s something unsatisfying about these actions. They are perhaps what Ahmed (Citation2004) calls ‘non-performative declarations of whiteness’: that is, while they purport to critique whiteness through the act of deletion of symbolic representations, they are in fact fantasies of transcendence. Jampol (Citation2020) reminds us, ‘When physical remnants of a difficult past are erased, it doesn’t make the underlying problem just go away. In fact, it’s often the opposite – erasure of such public reminders of repression makes it even more difficult to keep the discussion in the spotlight, scoring points for symbolic victory while preventing more lasting systemic change’ (para. 15). If Hilgard Hall’s epigraph and Eurocentric agricultural imagery were removed, there would be no magical disappearance of the settler-colonial ideology that produced the space in first place and continues to reproduce it through the scholarly activities conducted inside (cf. Lefebvre Citation1991).

In 2010, the Rausser College of Natural Resources released a Strategic Facilities Master Plan outlining a vision to renovate the Agricultural Complex and adjacent buildings, and Hilgard Hall is a priority capital improvement project, particularly for seismic retrofits (Noll and Tam Architects et al. Citation2010). While the report speaks extensively about how any renovation to the Agriculture Complex buildings will ‘retain their historic identity while providing cutting-edge research spaces for scientists and scholars’ (2), it neglects to take into account that this approach to preserve ‘historic identity’ legitimises white racial dominance while obfuscating simultaneous alternative histories and counternarratives.Footnote15

Here, I offer one possible vision for Hilgard Hall that attempts to enable the building to become a ‘spatial race traitor’ (to riff off of Ignatiev and Garvey’s Citation1996 term) through renovation and occupation (). Hilgard Hall’s next iteration will be the building’s third life: after its original construction in 1916–17, it had one major renovation in 1960–63 (Knapp Architects Citation2012). Drawing inspiration from paperson’s (Citation2017) concept of the ‘third university’ – with gestures to Soja’s (Citation1996) ‘thirdspace’ geographies, Gutiérrez’s (Citation2008) ‘third space’ sociocritical literacy, and UC Berkeley’s mighty Third World Liberation Front – Hilgard Hall’s third life might become a site for a ‘strategic reassemblage’ (paperson Citation2017, 44).

paperson reminds us that the ‘decolonial is always already amid the colonial’ (xvi). We could start by planting Native Californian seeds in the terraces of Hilgard Hall’s roof, so that the crops of those who have stewarded the land we call California since time immemorial crown the words ‘native values’. The hillside leading up to the building could be planted in nopal cactus. The prickly pear spines would be the new ‘Hill Guard’ to remind anyone entering the building that Mexican agricultural knowledge and labour is California. The Rausser College of Natural Resources could seek the expertise of colleagues in Ethnic Studies to design a permanent outdoor exhibit that traces the Chicanx and Filipinx history of the farmworker movement, including the Third World Liberation Front’s solidarity work in the 1960–70s. Hilgard Hall’s pathways could be lined with crops of the Black farmers who came to California during the Great Migration. The courtyard between the three buildings of the Agricultural complex could be dedicated to the production of Asian American agricultural practices. This ‘enclosure’ garden would speak back to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1862, California Alien Land Laws of 1913 and 1920, and multiple early 20th century Immigration Acts aimed at barring Asian immigrants. There could be a section of the garden commemorating the Japanese American farmers whose land and lives were stolen through internment in the 1940s. The garden could also include crops of the Hmong, Lao, Mien, and Cambodian refugees who have farmed in California since the American War in their homelands in the 1970s. While each of these agricultural interventions could be institutionalised through inclusion in the ‘official’ landscape design, they would be co-created with community organisations and Berkeley Student Farms, a coalition of eight student-led gardens throughout the Berkeley campus dedicated to peer-to-peer ‘movement building, meaningful inclusion, and equitable distribution of food, land, and knowledge through collective action and resistance’ (Berkeley Student Farms Citationn.d.). For several years, students of colour have already taught a ‘guerilla gardening’ course in the College’s interstitial spaces through Berkeley’s student-run Democratic Education at Cal (DeCal) Programme (Democratic Education at Cal Citation2019; Berkeley Student Farms Citationn.d.).

Inside the building, the soils that have been locked away for a century could, if so desired by Native Californian communities, be rematriated to their ancestral homes, with accompanying research and curricular activities on Indigenous scientific approaches to soil health. With the cabinets removed, the long corridor walls would be primed for a visual counternarrative to the white majoritarian chronicle carved on the friezes of the building’s epidermis. The images could be created using the specific artistic traditions of the Californians whose gardens will now surround the building. In the central foyer a wall panel could explicitly name the hegemonic whiteness of Hilgard Hall’s original design and explain these interventions. Berkeley could wrestle with its Eurocentric agricultural education by heeding Mills’s (Citation2017) call to ‘occupy liberalism’ for a radical agenda. Hilgard Hall’s classrooms could become spaces for an agricultural ‘travelling curriculum’, which Leonardo (Citation2018) describes as one where ‘the practice of knowledge [is] unsystematic (in the sense of abandoning originary thinking), unexpert (in the sense of reconstructing authority) and unexploratory (in the sense of positioning itself against discovery)’ (16). Black radical thought, Indigenous ecological knowledge, Chicanx studies, Asian American studies, critical social theory, and Western science would be necessarily uncomfortable but open-hearted travelling companions. Californians’ diverse agricultural knowledges, sociocultural constructions of rural life, and life-affirming resistances to white supremacy could be central to the curriculum. It could also address the post-colorblind (Leonardo Citation2020) iteration of whiteness so rampant in contemporary American rural life, not through the lens of an oversimplified Left Coast urban elitism, but as a topic of critical inquiry.

By happenstance, when I took a panoramic photo of the façade of Hilgard Hall midmorning on 26 February 2021, the late winter sun was rising over the southeast of the building, creating a tableau hauntingly similar to the composition of the 1872 John Gast painting, ‘American Progress’. Perhaps the most famous artistic rendition of Manifest Destiny, the painting depicts Indigenous people fleeing into the darkened western horizon, while white people armed with industry, agriculture, and education advance across the rural landscape out of the light of the eastern sunrise. In my own photograph, the rising sun obscures the epigraph’s final words. The modified inscription is an open-ended possibility ().

Acknowledgments

This paper was written on the territory of xučyun, the ancestral and unceded land of the Chochenyo speaking Ohlone people, the successors of the historic and sovereign Verona Band of Alameda County. This land was and continues to be of great importance to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and other familial descendants of the Verona Band.Footnote16

Gratitude to Alexii Sigona (Amah Mutsun Tribal Band), who is rescuing human society with Native values by conducting research on Native Californian environmental stewardship and land rights. Thank you to C.N.E. Corbin on elucidating the connection between City Beautiful and Spanish imaginary in Berkeley’s architecture; Joey Plaster for directing me to George Lipsitz’ writing on the Butler Library; Sine Hwang Jensen for digging up Eugene Hilgard’s writing on Native American soil health; and Aaron Alvarado for his inspiring work on settler rurality, racial capitalism, and knowledge production at the University of California. Thank you to the anonymous reviewers whose detailed suggestions improved this article. Special thanks to Zeus Leonardo for doing the teaching that has made it possible for me to become myself as a scholar (cf. Horton and Freire Citation1990).

The quoted student was interviewed under approval of the University of California, Berkeley, Office for the Protection of Human Subjects (Protocol #2020-06-13425).

Disclosure statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Direct quotes from Eugene Woldemar Hilgard are from his personal communications and unpublished memoir, available in the collection of the Hilgard Family Papers, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley https://oac.cdlib.org/search?style=oac4;titlesAZ=h;idT=UCb10879670x.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A horizontal band of decoration at the top of building, often above columns.

2. Hereafter ‘UC Berkeley’.

3. ESPM is an interdisciplinary biological, physical, and social science department formed in 1994 through the merging of several discipline-based agriculture departments. The original departments to inhabit Hilgard Hall were agronomy, citriculture, forestry, genetics, pomology, soil technology, and viticulture (Knapp Architects Citation2012). The Rausser College of Natural Resources is the current name for what was the College of Agriculture at the time that Hilgard Hall was built.

4. Since time immemorial, the land under discussion has been stewarded by Native custodians through Indigenous agricultural and ecological knowledge. In naming the ravages of settler colonialism on Native communities, I also acknowledge and honour their continual presence and resilience.

5. There is debate as to whether the early land-grant universities actually served many lower class Americans. For example, Sorber and Geiger (Citation2014) argue that they primarily served wealthy farm families and an expanding middle class.

6. Joseph LeConte’s publications promoting scientific racism, such as The Race Problem in the South (Citation1892), were a key factor in the decision by UC Berkeley to unname LeConte Hall in 2020 (University of California, Berkeley Citation2020).

7. To the best of my knowledge. It is quite possible that commentary revealing Hilgard’s racial views towards Native Americans, including descriptions of encounters with Native Californians, exist among his extensive fieldnotes and personal letters. While I spent substantial time in the UC Berkeley Bancroft Library archive pouring over the Hilgard Family Papers, I hardly made a dent in the cartons of materials written in English, Spanish, and German.

8. Deteriorating soil fertility was a primary concern of Senator Justin Morrill (after whom the Morrill Act is named) and among his justifications for settler expansion and the creation of nation-wide colleges of agriculture (Morrill Citation1858; Alvarado Citation2019).

9. See Bowers (Citation1971) on the urban-led Progressive Era ‘Country-Life’ reform movement.

10. Sgraffito is a decorative technique where a design is made by scratching through a layer of coloured plaster to reveal a base layer in a contrasting colour. Hilgard Hall is the only UC Berkeley campus building utilising sgraffito (Knapp Architects Citation2012).

11. Wheat was in fact the dominant agricultural commodity grown in California at the time of UC Berkeley’s founding (Walker Citation2004).

12. Interestingly, the architectural drawings of the building from 1916 show an alternate inscription: ‘To bring food for the peoples from the breast of the earth’ (Knapp Architects Citation2012, 124). This version still implies rescue by unnamed whites (the ones who do the ‘bringing’) but doesn’t place the same axiological emphasis on rural life. Of course the gendered element is telling: rational (male) science is necessary for the (female) earth to provide.

13. The Citrus Experiment Station was one of the University of California field stations set up through the statewide network of Agricultural Experiment Stations. In 1954, UC Riverside became a full UC campus.

14. Racial data are from October 2022 and gender data are from April 2019, as 2022 data list the gender of nine faculty members as ‘unknown’.

15. The first building in the Agricultural Complex to be renovated was Giannini Hall, which was completed in spring 2021 without addressing Amadeo Giannini’s white supremacist legacy. For an important study of the role of the Giannini Foundation in promoting racial capitalism in California agriculture, see Alvarado (Citation2019). In 2020, the College of Natural Resources was renamed the Rausser College of Natural Resources, after Gordon Rausser, a former college dean who negotiated the controversial $25 million contract between UC Berkeley and agricultural biotechnology company, Novartis. In fall 2021, both a painting and a bust of Rausser was installed in the Giannini Hall entryway, further entrenching the College’s adherence to hegemonic white agricultural research ideologies. For more on the Novartis contract, see: Rudy et al, (Citation2007).

16. See Native American Student Development, UC Berkeley (Citationn.d.).

References

- Ahmed, S. 2004. “Declarations of Whiteness: The Non-Performativity of Anti-Racism.” Borderlands, 3. 2 http://www.borderlands.net.au/vol3no2_2004/ahmed_declarations.htm

- Almaguer, T. 2009. Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California. New ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Alvarado, A. 2019. Reckoning the Rural: Racial Capitalism, the San Joaquin Valley, and the University of California. UC Riverside. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nb2m4nr.

- Applebaum, B. 2016. “Critical Whiteness Studies.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.5.

- Barrett, J. R., and D. R. Roediger. 1997. “How White People Became White.” In Critical White Studies: Looking Behind the Mirror, edited by R. Delgado and J. Stefancic, 402–406. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Berkeley Food Institute,2018. “Food and Agriculture Courses | UC Berkeley Foodscape Map.” https://food.berkeley.edu/foodscape/academic-units/food-and-agriculture-courses/

- Berkeley Student Farms, n.d. “Home | Berkeley Student Farms.” Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.studentfarms.berkeley.edu

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge Studies in Social Anthropology 16. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bowers, W. L. 1971. “Country-Life Reform, 1900-1920: A Neglected Aspect of Progressive Era History.” Agricultural History 45 (3): 211–221. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3741982.

- Cabrera, N. 2018. “White Immunity”: Working through the Pitfalls of “Privilege” Discourse. TEDxUofA. https://www.ted.com/talks/nolan_cabrera_white_immunity_working_through_the_pitfalls_of_privilege_discourse

- Davis, A. M., and R. Ernst. 2019. “Racial Gaslighting.” Politics, Groups & Identities 7 (4): 761–774. doi:10.1080/21565503.2017.1403934.

- Democratic Education at Cal. 2019. “About the DeCal Program.” https://decal.berkeley.edu/about/decal-program

- Evans, J. J., and W. B. Lees. 2021. “Introduction to the Special Issue on Reframing Confederate Monuments: Memory, Power, and Identity.” Social Science Quarterly 102 (3): 959–978. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12960.

- Fanshel, R. Z. 2021. The Morrill Act as Racial Contract: Settler Colonialism and U.S. Higher Education. Berkeley: University of California. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1cc0c4tw#author

- Gast, J. 1872. American Progress. Autry Museum of the American West. Los Angeles, California: Oil on canvas.

- Gebrial, D. 2018. “Rhodes Must Fall: Oxford and Movements for Change”. In Decolonising the University, In edited by G. K. Bhambra, D. Gebrial, and K. Nişancıoğlu, 19–36. Pluto Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/25936

- Gerencser, J., S. Rose, and M. Triller Doran. n.d. Locations of Off-Reservation Indian Boarding Schools in the U.S. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/teach/locations-reservation-indian-boarding-schools-us

- Giroux, H. 1997. “Rewriting the Discourse of Racial Identity: Towards a Pedagogy and Politics of Whiteness.” Harvard Educational Review 67 (2): 285–321. doi:10.17763/haer.67.2.r4523gh4176677u8.

- Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, Edited by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

- Gutiérrez, K. D. 2008. “Developing Sociocritical Literacy in the Third Space.” Reading Research Quarterly 43 (2): 148–164. doi:10.1598/RRQ.43.2.3.

- Harris, C. I. 1993. “Whiteness as Property.” Harvard Law Review 106 (8): 1707–1791. doi:10.2307/1341787.

- Hayden-Smith, R., and R. Surls. 2014. “A Century of Science and Service.” California Agriculture 68 (1): 8–15. doi:10.3733/ca.v068n01p8.

- Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style. Routledge.

- Hilgard, E. W. 1863. “Letter Addressed to ‘Dear Sir,’” 1863. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library.

- Hilgard, E. W. 1865. Letter to Julius Hilgard. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library.

- Hilgard, E. W. 1907. Biographical Memoir of Joseph LeConte, 1823–1901. Read Before the National Academy of Sciences, April 18, 1907. District of Columbia: Judd & Detweiler, Printers.

- Hilgard, E. W. n.d. Biographical Memoir (Unpublished). University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library.

- Hilgard Family. 1945. “Hilgard Family Papers, [Ca. 1848-1945].” Bancroft BANC MSS C-B 972.

- Hodgson, R. W. 1917. Hilgard Hall, a Gift of the Citizens of California: Dedicated Saturday, October the Thirteenth, Nineteen Hundred and Seventeen. Berkeley: University of California College of Agriculture.

- hooks, b. 1992. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press.

- Horton, M., and F. Paolo. 1990. We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change, Edited by Brenda Bell, John Gaventa, and John Marshall Peters. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Huhndorf, S. M. 2001. Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Ignatiev, N., and J. Garvey. 1996. “Abolish the White Race: By Any Means Necessary.” In Race Traitor, edited by N. Ignatiev and J. Garvey. New York: Routledge.

- Jampol, J. 2020. “Tearing Down Statues Won’t Undo History.” Foreign Policy (blog). Accessed May 5, 2021. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/30/tearing-down-confederate-lenin-east-germany-hungary-statues-wont-undo-history/.

- Jenny, H. 1961. E. W. Hilgard and the Birth of Modern Soil Science., 3. Pisa: Collana Della Rivista “Agrochimica”.

- Kimmerer, R. 2018. “Mishkos Kenomagwen, the Lessons of Grass: Restoring Reciprocity with the Good Green Earth.” In Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability, edited by Nelson, M. K. and D. Shilling, 27–56. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kipling, R. 1899. Poems - The White Man’s Burden. http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poems_burden.htm

- Knapp Architects, 2012. “The University of California, Berkeley, Hilgard Hall: Historic Structure Report.” https://works.bepress.com/williamriggs/15/

- LeConte, J. 1892. The Race Problem in the South. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Libraries.

- Lee, R. 2020. Morrill Act of 1862 Indigenous Land Parcels Database. High Country News. https://github.com/HCN-Digital-Projects/landgrabu-data

- Lee, R., and T. Ahtone. 2020. “Land-Grab Universities.” High Country News, March. https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Leonardo, Z. 2004. “The Color of Supremacy: Beyond the Discourse of ‘White Privilege.’.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 36 (2): 137–152. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2004.00057.x.

- Leonardo, Z. 2013. Race Frameworks: A Multidimensional Theory of Racism and Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Leonardo, Z. 2015. “Contracting Race: Writing, Racism, and Education.” Critical Studies in Education 56 (1): 86–98. doi:10.1080/17508487.2015.981197.

- Leonardo, Z. 2018. “Dis-Orienting Western Knowledge.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 36 (September): 7–20. doi:10.3167/cja.2018.360203.

- Leonardo, Z. 2020. “The Trump Presidency, Post–Color Blindness, and the Reconstruction of Public Race Speech.” In Trumpism and Its Discontents. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Public Policy Press. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/trumpism-and-its-discontents/the-trump-presidency.

- Leyh, B. M. 2020. “Imperatives of the Present: Black Lives Matter and the Politics of Memory and Memorialization.” Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 38 (4): 239–245. doi:10.1177/0924051920967541.

- Lipsitz, G. 2007. “The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape.” Landscape Journal 26 (1): 10–23. doi:10.3368/lj.26.1.10.

- Lipsitz, G. 2008. “Breaking the Chains and Steering the Ship: How Activism Can Help Change Teaching and Scholarship.” In Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship 1sted. edited by, C. R. Hale, 88–112. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

- Lipsitz, G. 2018. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics. Twentieth anniversary ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press.

- Locke, J. 1978. “Of Property.” In Property: Mainstream and Critical Positions, edited by C. B. MacPherson, 15–28. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt1287ps1.5

- Manke, K. 2020. “Berkeley Public Health Announces Plans to Rename, Repurpose Former Eugenics Fund.” Berkeley News, October 26, 2020. https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/10/26/berkeley-public-health-announces-plans-to-rename-repurpose-former-eugenics-fund/.

- Mayes, C. 2018. Unsettling Food Politics: Agriculture, Dispossession and Sovereignty in Australia. London; New York: Rowman & Littlefield International.

- McIntosh, P. 2004. “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies.” In Race, Class, and Gender: An Anthology, edited by M. L. Andersen and P. H. Collins. 5th ed., pp. 70–81. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- Mills, C. 1997. The Racial Contract. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Mills, C. 2007. “White Ignorance.” In Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, edited by S. Sullivan and N. Tuana, 11–38. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Mills, C. 2017. Black Rights/White Wrongs: The Critique of Racial Liberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Morrill, J. S. (1858). Speech of Hon. Justin S. Morrill, of Vermont, on the Bill Granting Lands for Agricultural Colleges; Delivered in the House of Representatives, April 20. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100762188

- Morrison, T. 1993. “On the Backs of Blacks.” Time, December 2, 1993. http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,979736,00.html.

- Myers, K. 2013. “White Fright: Reproducing White Supremacy Through Casual Discourse.” In White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism, edited by A. Doane and E. Bonilla-Silva, 131–146. Routledge.

- Nash, M. A. 2019. “Entangled Pasts: Land-Grant Colleges and American Indian Dispossession.” History of Education Quarterly 59 (4): 437–467. doi:10.1017/heq.2019.31.

- National Archives and Records Administration. 1862 July 2. “Morrill Act (1862).” https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-10285/pdf/COMPS-10285.pdf.

- National Park Service. 2019 September 20. “Homesteading by the Numbers – Homestead National Historical Park.” https://www.nps.gov/home/learn/historyculture/bynumbers.htm.

- National Park Service. 2021 February 8. “African American Homesteaders in the Great Plains.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/african-american-homesteaders-in-the-great-plains.htm.

- Native American Student Development, University of California, Berkeley, n.d. “Ohlone Land | Centers for Educational Justice & Community Engagement.” Accessed October 19, 2021. https://cejce.berkeley.edu/ohloneland.

- Noll and Tam Architects, University of California, Berkeley, College of Natural Resources, Univesrity of California, Berkeley, Capital Projects, 2010. College of Natural Resources Report. “College of Natural Resources Report.” https://nature.berkeley.edu/site/forms/pdf/CNR_Report.pdf.

- Omi, M., and H. Winant. 2015. Racial Formation in the United States. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- paperson, L. 2017. A Third University is Possible. University of Minnesota Press. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/a-third-university-is-possible

- Roediger, D. R. 1994. Towards the Abolition of Whiteness: Essays on Race, Politics, and Working Class History. London; New York: Verso.

- Roediger, D. R. 2007. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. Revised and new Edition. Haymarket Series ed. London; New York: Verso.

- Rose, E. P. F., and C. P. Nathanail. 2000. Geology and Warfare: Examples of the Influence of Terrain and Geologists on Military Operations. London, United Kingdom: Geological Society of London.

- Rousseau, J.J. 2007. The Social Contract: And, Discourses, Translated by G. D. H. Cole. Hawthorne, CA: BN Publishing.

- Rudy, A. P., L. Busch, D. Coppin, T. Ten Eyck, C. Harris, J. Konefal, and B. T. Shaw. 2007. Universities in the Age of Corporate Science: The UC Berkeley-Novartis Controversy. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press.

- Said, E. W. 1994. Culture and Imperialism. 1st Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books.

- Slate, F. 1919. “Biographical Memoir of Eugene Woldemar Hilgard.” National Academy of Sciences. http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/hilgard-eugene.pdf.

- Sleeter, C. E. 1993. “How White Teachers Construct Race.” In Race, Identity, and Representation in Education, edited by C. McCarthy and W. Crichlow, 157–171. London; New York: Routledge.

- Soja, E. W. 1996. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-And-Imagined Places. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Sorber, N. M., and R. L. Geiger. 2014. “The Welding of Opposite Views: Land-Grant Historiography at 150 Years.” In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Volume 29, edited by M. B. Paulsen, 385–422. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-8005-6_9.

- Stadtman, V. A. 1970. The University of California, 1868-1968. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Stein, S. 2017. “A Colonial History of the Higher Education Present: Rethinking Land-Grant Institutions Through Processes of Accumulation and Relations of Conquest.” Critical Studies in Education 61 (2): 212–228. doi:10.1080/17508487.2017.1409646.

- Taylor, P. S. 1945. “Foundations of California Rural Society.” California Historical Society Quarterly 24 (3): 193–228. doi:10.2307/25155919.

- Trafzer, C. E., J. Allen Smith, and L. Sisquoc. 2017. Shadows of Sherman Institute: A Photographic History of the Indian School on Magnolia Avenue. Pechanga, CA: Great Oak Press.

- Twine, F. W., and C. Gallagher. 2008. “The Future of Whiteness: A Map of the ‘Third Wave’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31 (1): 4–24. doi:10.1080/01419870701538836.

- United States Department of the Interior and Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service. 1982. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form. University of California Multiple Resource Area.” https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/f57a5eaf-5772-449f-8f05-0252c204b52c.

- University of California, Berkeley. 2020 September 25. “Office of the Chancellor Building Name Review Committee.” https://chancellor.berkeley.edu/sites/default/ files/bnrc_leconte_recommedation.pdf

- University of California, Berkeley. 2022 October. “CalAnswers BI Interactive Dashboards - HR Census.” https://calanswers.berkeley.edu/home.

- University of California, Berkeley. n.d. “Office of the Chancellor, Building Name Review Committee. “Accessed March 11, 2023. https://chancellor.berkeley.edu/task-forces/administrative-committees/building-name-review-committee#:~:text=The%20UC%20Berkeley%20Building%20Name,campus%20building%20should%20be%20removed.

- University of California, Riverside, n.d. “Our History.” College of Natural & Agricultural Sciences. Accessed May 4, 2021. https://cnas.ucr.edu/about/history.

- Walker, R. 2004. The Conquest of Bread: 150 Years of Agribusiness in California. New York: New Press.

- Wolfe, P. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. doi:10.1080/14623520601056240.

- Wollenberg, C. M. 2008. Berkeley: A City in History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Young, P. S. K. 2006. California Vieja: Culture and Memory in a Modern American Place. Berkeley: University of California Press.