ABSTRACT

Alternatives to inpatient psychiatric care for adolescents are needed given the growing need for yet limited access to inpatient psychiatric unit beds. We developed and tested an alternative model, the youth crisis stabilization unit, which provides intensive cognitive-behavioral, family-centered treatment to youth and their parents/guardians in a nonmilieu setting. Charts of 118 adolescents (12 to 18 years) eligible for both and admitted to either the youth crisis stabilization unit (n = 73) or inpatient psychiatric unit (n = 45) within the same pediatric hospital between January 2017 and June 2017 were reviewed retrospectively. Length of stay, readmission rates, and time to readmission were compared for adolescents admitted primarily due to suicidal ideation and/or attempt. No significant differences were found across units on demographic or clinical characteristics. Length of stay was significantly shorter on the youth crisis stabilization unit (M = 4.52, SD = 1.37) compared with the IPU (M = 10.31, SD = 9.03, p < .001). Readmission rates (p = .619) and time to readmission (p = .596) did not differ. The youth crisis stabilization unit treatment model merits further study as an alternative to traditional inpatient care.

The standard of care for acutely suicidal individuals who are unable to be safely maintained in the community is inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (Shain, Citation2016). However, in recent years, the number of inpatient beds for youth with mental health issues has not kept pace with the demand (Blader, Citation2011; Edgcomb et al., Citation2020). This is driven in large part by increasing rates of suicide-related behaviors. Suicidal ideation and attempts are significant risk factors for suicide (Bridge, Goldstein & Brent, Citation2006). Nearly one in five (18.8%) U.S. high school students have reported severe suicidal thoughts over the past 12 months, with 8.9% indicating they attempted suicide during that period (Ivey-Stephenson et al., Citation2019). Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for adolescents ages 15 to 19, with 11.4/100,000 deaths annually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Citation2020).

Lower levels of care, including partial hospitalization programs (PHPs), intensive outpatient programs (IOPs), and brief suicide-risk-reduction interventions deployed in emergency departments (EDs) are important parts of a continuum of care (Asarnow & Goldston, Citation2021; Leffler et al., Citation2020), but depending on degree of suicidal risk, these may be insufficient to provide adequate safety. Inpatient psychiatric units (IPUs) traditionally provide individual and group therapy, medication management, case management, occupational and recreational therapy evaluations with subsequent treatment, and educational interventions as required. IPU program innovations include providing evidence-based psychotherapy to reduce readmission rates and emergency-department visits (Wolff et al., Citation2018). However, family involvement on IPUs is variable (Hayes et al., Citation2018). This is despite the fact that the importance of family involvement in treating youth has been demonstrated in multiple settings with multiple diagnoses (Wendel & Gouze, Citation2016). In particular, family-based care has been found to successfully decrease need for inpatient hospitalization in youth (Wharff et al., Citation2012), while outpatient family-focused cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) with adolescents in crisis has demonstrated reductions in suicidality, depression, and nonsuicidal self-injury (Esposito-Smythers et al., Citation2019).

In 2011, given community needs and the psychiatric inpatient bed shortage, a Midwestern pediatric hospital developed a model to treat youth who previously had been placed in “holding beds” elsewhere in the community or in general pediatric observational beds (referred to as boarders) while awaiting inpatient psychiatric care in that same hospital. Intensive crisis intervention (ICI) was provided, which consisted of psychiatric assessment, medication management, and multiple individual CBT sessions and several family therapy sessions per day. Once ICI became the standard of care for these patients, many were able to be sent home to receive outpatient care after a few days of treatment, rather than being transferred to the hospital’s IPU. Given this model’s success in providing short-term intensive treatment for youth at acute suicidal risk, the hospital expanded this model by creating a youth crisis stabilization unit (YCSU) designed to implement ICI as an alternative to traditional IPU treatment. An open trial provided support for the YCSU’s feasibility and acceptability; ICI was associated with significant reductions in suicidal ideation, improvements in functioning 3 months after admission, and high levels of treatment satisfaction were reported by parents (McBee et al., Citation2019).

The purpose of this study was to compare demographics, clinical characteristics, average length of stay (ALOS), readmission rates, and time to readmission for patients eligible for admission to both the YCSU and IPU and admitted to one of them, based on first availability, at this same hospital.

Methods

Treatment

YCSU

The YCSU team includes a psychiatrist, masters-level clinicians trained and supervised in ICI, nursing staff, and recreational therapists. Based on the youth’s assessment, a case conceptualization is developed that focuses on maladaptive responses to stress and guides treatment-plan development, which is formulated with the adolescent. Treatment is based on the cognitive–behavioral model of suicidality (Esposito-Smythers et al., Citation2019). Key to this intervention is its intensity, focused on the youth and family. Adolescents participate in 2 to 3 individual sessions and 1 to 2 family sessions daily, each generally lasting 30 to 90 minutes, for an average of 200 minutes of therapy per day. Therapy is provided by masters level clinicians, who are assigned two patients at a time. They work three consecutive 12-hour shifts, allowing for continuity of care with families and time to communicate with the overall team in rounds and to document care. Unlike with traditional IPUs, patients do not interact with one another or attend group therapy.

In individual and family sessions, parents and adolescents work to develop more adaptive cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to stressful situations. Motivational interviewing strategies are deployed to capitalize on the crisis, with the intention of maximizing change in the adolescent and family. Individual sessions address problem areas through psychoeducation, self-monitoring, behavioral-skills training (e.g., relaxation training, behavioral activation, problem solving, social-skills training), cognitive restructuring, and/or exposure experiments. Family interventions focus on enhancing communication skills, problem-solving skills, and emotion regulation for all participants. Family sessions focus on reviewing what patients have learned in their individual sessions, allowing parents to understand their child’s progress and the tools learned. These sessions also afford an opportunity to discuss precipitating triggers of the crisis and to troubleshoot how to avoid crisis responses in the future. Adolescents complete assignments between sessions that reinforce learning from their therapy sessions. Team meetings (i.e., rounds) occur daily to coordinate care and monitor patient progress in treatment.

Linkage to ongoing outpatient care begins at the time of admission and is completed at termination. Safety planning also begins when the child is admitted. Parents receive information highlighting the importance of close supervision and monitoring at home. A personal safety plan is formulated using resources the adolescent has learned. The written safety plan, adapted from Stanley and Brown (Citation2012), outlines warning signs, internal and external coping strategies, ways to limit access to lethal means, reasons for living, and professionals/agencies to contact for help. Families learn when and how to use their plans and problem solve ways to eliminate barriers to implementation.

IPU

The IPU provides comprehensive assessment and treatment services to youth with significant psychiatric difficulties and to their families. At the time of this study, the treatment team included a child and adolescent psychiatrist, psychiatric nursing staff, behavioral-health-care clinicians, care managers, occupational therapists, and teachers. Psychologists and parent partners provided consultation when indicated.

An individualized treatment plan is developed by the entire treatment team, including the patient and caregivers, and includes initial planning for discharge with the primary treatment goal being stabilization of acute psychiatric symptoms. Programming is based on a trauma-informed biopsychosocial approach. Symptoms and behaviors that led to admission are targeted through a milieu-based model of care and therapeutic group programming. Ongoing psychiatric care and individual and family therapy, as indicated, is provided by psychiatric providers and behavioral-health clinicians but at a lower daily frequency than in ICI. Youth also participate in rehabilitative therapy and receive educational services.

Allocation

Youth eligible for both the YCSU and IPU are placed on both wait-lists in the emergency department to provide them with the first available treatment bed. The following criteria must be met to be eligible for either unit: (1) The youth is (a) developmentally capable of participating in cognitive-based therapeutic interventions; (b) presenting with suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, a suicide attempt, and/or decompensating depression and/or anxiety; (c) currently unsafe to return to the community; (d) not actively aggressive/behaviorally dysregulated; and (e) willing to engage in treatment and (2) the parent is (a) admitting their child voluntarily and signs consent for admission to either unit; and (b) willing to engage in treatment. All youth eligible for YCSU are also eligible for IPU; some youth eligible for IPU are not eligible for YCSU (e.g., acutely manic or psychotic, exhibiting significant developmental delays, displaying severe aggression). These youth were not considered for this study.

Evaluation

Institutional review board approval was received prior to commencing the study. Quality-improvement staff extracted electronic-health-record (EHR) data of all patients ages 12 to 18 admitted to the hospital’s emergency department for suicidal ideation or suicide attempt between January 2017 and June 2017 (N = 646). These records were provided to an independent evaluator, who completed a retrospective chart review. A minority of patients (n = 118, 18%) were eligible for admission to both the YCSU and IPU. Their EHR data were abstracted to obtain demographic and service utilization data. Data were deidentified prior to being made available to the data analytic team.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize demographic and clinical characteristics. An independent samples t test was used to compare ALOS and a chi-squared test was utilized to compare 180-day readmission rates between the two units. Time to first readmission was calculated using survival analysis.

Results

Sample description

All patients (N = 118) met criteria for psychiatric hospitalization on either unit. Youth were treated either in the YCSU (n = 73) or IPU (n = 45). The sample was primarily female (78.0%) and Caucasian (60.2%; African American constituted 19.5% of the sample; Asian, 3.4%; multiracial, 13.6%; Hispanic, 3.4%) with an average age of 14.4 years (SD = 1.6, range = 12–18). Primary reasons for admission were suicidal ideation (61.0%) or suicide attempt (26.3%). A majority of patients (87.3%) received a mood-disorder diagnosis. Other diagnoses included anxiety disorder, 50.0%; substance-use disorder, 8.5%; disruptive-behavior disorder, 6.8%; and miscellaneous, 7.6%. This was the first psychiatric hospitalization for nearly all participants (94.1%). Almost all participants (94.1%) were discharged to home. These demographic and clinical variables did not differ for youth treated in the YCSU versus IPU ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients admitted to the youth crisis stabilization unit (YCSU) and inpatient psychiatric unit (IPU)

Comparison of outcomes between units

Average length of stay (ALOS) measured in days was significantly shorter for YCSU patients (M ± SD = 4.52 ± 1.37, median = 4, range = 1–9) than for IPU patients (M ± SD = 10.31 ± 9.03, median = 8, range = 3–58, p < .001). To reduce the impact of outliers, we winsorized data and recalculated ALOS differences. After applying 90% winsorization, ALOS remained significantly briefer for YCSU patients (M + SD = 4.53 + 1.16, median = 4, range = 3–7) than for IPU patients (M + SD = 9.38 + 5.07, median = 8, range = 4–22; p < .001). Two YCSU patients had LOS > 7 days and two IPU patients had LOS > 22 days.

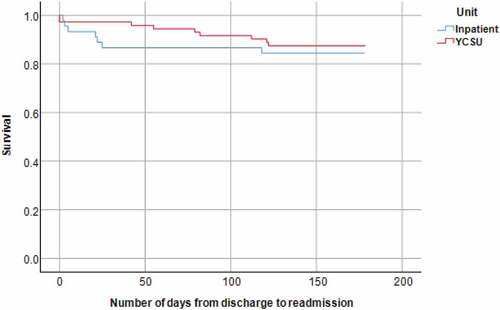

After discharge, five patients (4%) were readmitted within 7days. Of these, two (3%) were YCSU patients and three (7%) were IPU patients (Fisher’s exact test [FET], p = .37). Within 30 days, eight patients (7%) were readmitted; of these, two (3%) were YCSU patients and six (13%) were IPU patients (FET, p = .052). Within 90 days, 12 patients (10%) were readmitted; of these, six (8%) were YCSU patients and six (13%) were IPU patients (FET, p = .53). Within 180 days, 16 patients (14%) were readmitted; of these, nine (12%) were YCSU patients and seven (16%) were IPU patients (χ2 = 0.25, p = .62). Days to readmission did not differ significantly for the two units (See , p = .60).

Figure 1. Comparison of time to readmission for the youth crisis stabilization unit (YCSU) and inpatient psychiatric unit (IPU)

In terms of cost, per diem charges were 38% higher on the YCSU compared to IPU; however, total YCSU charges were 42% lower than total IPU charges due to the shorter ALOS. While a complete cost-analysis is beyond the scope of this study, insurance companies are increasingly covering the higher per diem due to the lower total cost of hospitalization on the YCSU (personal communication, Georgiana Roberts business manager, 11/20/20).

Discussion

Hospital admissions for suicide attempts and other crises have risen dramatically for adolescents (Blader, Citation2011; Edgcomb et al., Citation2020). As a result, systems of care are seeking alternatives to provide safe and effective care for these high-risk youth. Our hospital system developed a specialized unit, the YCSU, to provide brief, intensive care targeting such high-risk youth. Key features of the YCSU treatment model are intensive therapy focused on the youth and family with no inclusion of milieu or group therapy. A prior open-label study indicated feasibility and acceptability of this model of care; patients experienced significant reductions in suicidal ideation, improvements in functioning three months postadmission, and high levels of parent-reported treatment satisfaction (McBee et al., Citation2019).

In this further examination, youth who met eligibility criteria for both the YCSU and IPU and who were ultimately hospitalized on the YCSU spent, on average, nearly six fewer days (four fewer median days) in the hospital, with no difference in 180-day readmission rates or time to readmission. Thus, for youth eligible for admission to either unit, essentially twice as many can be treated on the YCSU compared to the IPU, thereby, addressing the very real concern about acute-care bed shortages. As youth in this study were eligible for admission to either unit but admitted to the unit with the first available opening, it is reasonable to consider that differences in length of stay reflect differences in treatment intensity and focus (i.e., individual/family versus individual/milieu–group/family) between the two units.

Notably, on a national level, 38% of youth discharged from psychiatric hospitals are readmitted within one year; over half (57%) of these youth are readmitted within 90 days of discharge (Fontanella, Citation2008). In addition, youth with suicidal ideation are readmitted twice as often as youth without suicidal ideation (Edgcomb et al., Citation2020). Cumulatively, this suggests that both the YCSU and IPU 180-day readmission rates (12% and 16%, respectively) are relatively low.

Study limitations include a retrospective design, small sample size, lack of randomization, absence of a routinely collected measure of suicidality, lack of detail regarding youth not discharged to home (i.e., if YCSU youth were discharged to an IPU, this could be considered a “failure” of the placement), and a single institution patient population. While the YCSU had a nominally lower readmission rate, this difference was insignificant. Further investigation utilizing a prospective, randomized design and a larger sample would allow for a more definitive exploration of the potential benefits of a YCSU model of clinical care for high-risk youth.

Conclusion

A novel model of short-term psychiatric care for high-risk youth that includes intensive individual and family therapy without a focus on milieu or group therapy has promising preliminary results. In addition to previously published feasibility and acceptability data, this study indicates that patients treated on the YCSU were discharged 4–6 days earlier than those treated on a traditional inpatient psychiatric unit with no difference in 180-day readmission rates or time to readmission. Further investigation of the YCSU model of care is warranted.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Bridge receives research grant funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); he is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Clarigent Health. Dr. Fristad receives research support from Janssen; royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, Child & Family Psychological Services, Guilford Press, and JK Seminars; and editorial support from Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Other authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Asarnow, J. R., & Goldston, D. (2021). Introduction to the special issue: Quality improvement for acute trauma-informed suicide prevention care. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 6(3), 303–306. doi:10.1080/23794925.2021.1961645

- Blader, J. C. (2011). Acute in-patient care for psychiatric disorders in the United States, 1996 through 2007. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(12), 1276–1283. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.84

- Bridge, J. A., Goldstein, T. R., & Brent, D. A. (2006). Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3–4), 372–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. (2020). Underlying cause of death 1999–2019 on CDC WONDER online database, released in 2020. Data are from the multiple cause of death files, 1999–2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the vital statistics cooperative program. Retrieved April 29, 2021, from http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

- Edgcomb, J. B., Sorter, M., Lorgerg, B., & Zima, B. T. (2020). Psychiatric readmission of children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatric Services, 71(3), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900234

- Esposito-Smythers, C., Wolff, J. C., Liu, R. T., Hunt, J. I., Adams, L., Kim, K., Frazier, E. A., Yen, S., Dickstein, D. P., & Spirito, A. (2019). Family-focused cognitive behavioral treatment for depressed adolescents in suicidal crisis with co-occurring risk factors: A randoized trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13095

- Fontanella, C. A. (2008). The influence of clinical, treatment, and healthcare system characteristics on psychiatric readmission of adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(2), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012557

- Hayes, C., Simmons, M., Simons, C., & Hopwood, M. (2018). Evaluating effectiveness in adolescent mental health inpatient units: A systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 498–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12418

- Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Demissie, Z., Crosby, A. E., et al. (2019). Suicidal ideation and behaviors. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(1), 47–55.

- Leffler, J. M., Junghans-Rutelonis, A. N., & McTate, E. A. (2020). Feasibility, acceptability, and considerations for sustainability of Implementing an integrated family-based partial hospitalization program for children and adolescents with mood disorders. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 5(4), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1759471

- McBee-Strayer, S. M., Thomas, G. V., Bruns, E. M., Heck, K. M., Alexy, E. R., & Bridge, J. A. (2019). Innovations in practice: Intensive crisis intervention for adolescent suicidal ideation and behavior – An open trial. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(4), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12340

- Shain, B. (2016). Committee on adolescence: American academy of pediatrics committee on adolescence: Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics, 138(1), e20161420. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1420

- Stanley, B., & Brown, G. K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Science Direct: Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256–264. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.01.001.

- Wendel, R., & Gouze, K. R. (2016). Family-based assessment and treatment. In M. K. Dulcan (Ed.), Dulcan’s textbook of child and adolescent psychiatry (pp. 937–958). American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Wharff, E. A., Ginnis, K. M., & Ross, A. M. (2012). Family-based crisis intervention with suicidal adolescents in the emergency room: A pilot study. Social Work, 57(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sws017

- Wolff, J. C., Frazier, E. A., Weatherall, S. L., Thompson, A. D., Liu, R. T., & Hunt, J. I. (2018). Piloting of COPES: An empirically informed psychosocial intervention on an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 28(6), 409–414. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2017.0135