ABSTRACT

At the end of the nineteenth century, the autonomous mobility provided by bicycles and tricycles created a mobile imaginary that paved the way for automobility. Through the course of the twentieth century, the growth and decline of cycling mobilities was inseparably entangled with the rise of a range of motor-mobilities (two and four wheeled). Yet cycling persists and is championed widely as a contender for future mobility in post-growth societies. However, the hegemonic position reached by automobility as a dominant system has led to closure of political non-car mobility imaginaries. Reaching targets for Carbon reduction. will entail dramatic transformation of mobility scapes. This paper explores the possibilities and problems inherent in formulating vélomobility as a system of autonomobility, paying special attention to its alignment with the range of radical alternatives clustered around degrowth and pluriversal thought as promising ways to think and act beyond the unsustainable carbon economy. It first examines the challenges of imagining vélomobility not just as a set of practices but cognitively, through its conceptual construction not as an inverse of automobility but as challenge to the political underpinnings of automobility. Second, it considers vélomobility through a set of propositions to reimagine mobility regimes and assess relevant resources from political theory. The final section reverses the gaze and asks what the reconsideration of vélomobility as described previously can bring to the broader discussion of autonomobility.

1. Part one. Introduction

1.1. Defining vélomobility

Among recent studies on cycling mobilities, the term vélomobility is increasingly being used to explore and develop images of post car mobility systems (Furness Citation2007; Pesses Citation2010; Koglin Citation2013; McIlvenny Citation2015; Cox Citation2019). The terminology is a conscious response to critical explorations of automobilities, where automobility refers not just to the practices of travel by car, but to the mobility systems comprised of numerous elements (spatial and temporal) and dimensions (political, economic, social and discursive) in which motoring is entangled and from which the motor car cannot be separated (Featherstone, Thrift, and Urry Citation2005; Böhm et al. Citation2006; Paterson Citation2007; Geels et al. Citation2012).

At one level, the linguistic claim posed by the term vélomobility reflects a deliberate echo of automobility. Identifying the dominant, even hegemonic position of automobilities within the wider mobility scape vélomobility, as an analytic connotes an alternative mobility system in which the power of automobility is overthrown and is replaced by the suggestion of regimes in which cycle mobilities predominate. Yet this replacement approach misses a central feature of a systems analysis; namely, that within the system of automobility, the practices of driving, and the motor vehicles themselves are relatively marginal. The vital factors are those multiple, entangled components that comprise the system eloquently described by Cass and Manderscheid (Citation2019):

“the steel-and-petroleum-car itself, its production, fuel and infrastructure industries, the policies that create automobile landscapes that separate work, residence and other activities in space, as well as the discursive and cultural association of cars with freedom and autonomy. Modern lifestyles that archetypally centre on one-family-houses in suburbia, shopping centres and leisure facilities on the edge of cities represent the ideal of the ‘good life’ under automobility. The perspective on automobility as a system (or as a regime or dispostif) underlines on the one hand its deep entanglement with the organisation of the social and everyday life, as well as its centrality in the current regime of economic accumulation and, on the other hand, its dynamics of self-perpetuation and continuous self-reinvention.”

The dynamics of self-perpetuation and self-reinvention easily stretch to the substitution of the steel-and-petroleum-car. Faced with the potential for the reinvention of automobility as a supposedly “greener” practice through the advent of driverless and e-motoring (Cass and Manderscheid Citation2010; Manderscheid Citation2018) the return to the core analysis of automobility highlights a keystone of its regime as the capacity to induce and (re)produce a culture of dependence. In proposing, even demanding, a greater emphasis on mobility justice, Cass and Manderscheid (Citation2018) develop the concept of autonomobility as a novel systems frame, designed to encapsulate a break with the dependencies built into closed mobility systems. A characteristic of closure in socio-technical systems is that they lock-in developmental trajectories through systems of dependence on exogenous input. That is, the technologies deployed in closed systems minimise the possibility of localised control over their use and application in practice. This critique of system closure is often coupled with critical observation of the link of such systems to particular economic modes of production, reliant on consumption and waste, reproduced through constant stress on innovation and obsolescence (Edgerton Citation2006).

In proposing vélomobility as an alternative way of thinking about the role of cycling within a mobility system, this paper responds to the crucial question opposed by Latham and Wood (Citation2015, 317): “How might it be possible to think about bikes not as some kind of anomaly within the motor vehicle–pedestrian divide (a mode that oscillates between the two master categories), but as a wholly different entity of movement?”. It also begins an exploration that seeks to address the concerns of Giulio et al. (Citation2020). “[U]ncovering the constituents, processes and characteristics of car-dependent transport systems”, they show that “moving past the automobile age will require an overt and historically aware political program of research and action” (Giulio et al. Citation2020, 1), concluding that, “The cultural underpinnings of car dependence go beyond just car travel and are connected to the very idea of travel as an intrinsically desirable practice” (10). However, the hegemonic position reached by automobility as a dominant system has led in practice to closure of political non-car mobility imaginaries. While practical considerations of alternative modal practices, such as dynamic public transport systems, MaaS, SMART cities and multimodal travel plans are growing, all these initiatives remain bounded by frameworks of automobility. Automobility retains its hegemony by mutating and co-opting practices that otherwise might be conceived as challenges. Explorations of cycle-friendly infrastructures and practices remain framed by, and shaped within, the dominance of automobility. Even progressive imaginations of cycle-friendly futures are often locked into a future imaginary forged under the shadow of automobility. To break this deadlock requires, as Levitas (Citation2013) argues, utopia as method. This requires engagement with the world of daydreams, of imagination, of worlds of affect as well as the technological and spatial arrangements that enable autono-mobility as discussed by other papers in this special issue.

If vélomobility is to offer the possibility of a mobility regime “after the car” (Dennis and Urry Citation2009) then it cannot replicate those features of automobility that make automobility problematic from the perspective of mobility justice. A meaningful system of mobility after the car cannot rely on simple vehicular substitution, the replacement of the steel and petroleum vehicle with another, more “environmentally friendly” vehicle within the systemic social and political frameworks of automobility. Nor, I argue, can vélomobility as a mobility system “after the car” be meaningfully framed simply as an (antithetical) inversion of automobility. Any technology necessarily has its systemic dimensions and requires a degree of dependence on exogenous expertise for its operation and maintenance. These are unavoidable except perhaps in the most extreme techno-primitive visions. However, serious consideration must be given to outlining at least some of the relevant parameters of vélomobility as a mobility practice and how it might serve to deconstruct the closures inherent in automobility.

1.2. Vélomobility and automobilism

Before we can think about vélomobility as an autonomobile practice, we need first to ask how cycling practices have been, and remain, constructed. Across the span of the twentieth century, cycling practices have been performed and imagined in the context of the car. That is, almost from the advent of the safety bicycle, and certainly since the advent of the mass-produced bicycle, cycling has been simultaneously shaped by automobilism and automobility. Mom (2015) employs the term automobilism, as distinct from automobility, to indicate a cultural movement over time that embeds automobile practices within the dominant culture. Using both terms in parallel enables us to distinguish discursive cultures and practices from socio-technical systems and their political theorisation. It should be further noted that the discursive and socio-technical systems of both driving and cycling are also fluid and subject to change over time.

Both cycling and motoring (including motorcycling) originally existed mainly as pastimes exclusive to a limited population with access to both finance and the leisure hours required for their pursuit. While they did so, the relation between the two was unvexed. A relatively seamless continuity and exchange existed between the key actors and advocates for both. This close harmony is visible in the print history of cycling and motoring magazines and the journalists who wrote for them, for example (see Armstrong Citation1946). That cycles and cars were products of the same manufacturers and similarly placed them together as companions not rivals. Noteably, the re-engagement of leading European motor manufacturers with cycle production in the twenty-first century points to a reconfiguration of automobility with a series of vehicular substitution practices. Only later, and especially with the emergence of mass cycling, did divergence became strongly marked and cycling become the “other” of automobile practices. Stigmatised and alienated, the cyclist became a hindrance to the car, a contest spelled out in the clear language of social class conflict: the car the enemy of the cyclist (Cox Citation2014). As both precursor and antithesis, cycling’s persistence became a conceptual embarrassment to visions of an automobile society. Before considering how we might understand future vélomobility as autonomobility we need to briefly consider cycling’s tangled relationship with historical automobilism.

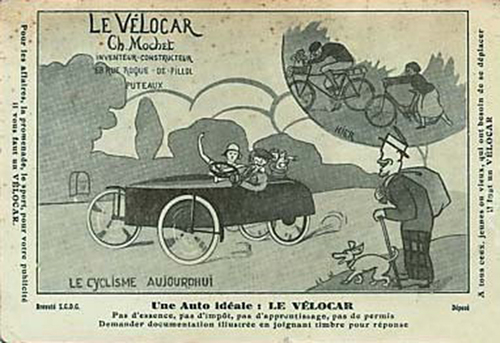

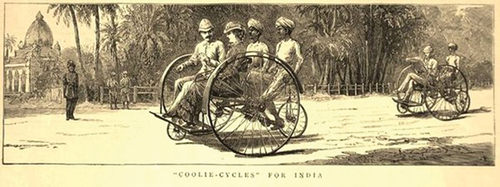

During the period in which cycling was conducted on car-free roads, it was initially and almost exclusively an activity of social élites and frequently served to reinforce and highlight distinctions of class and gender (Friss Citation2015). Further, its practices were highly racialized, either through segregation or within imperial codes of subjugation. Perhaps no more vividly are these hierarchies of power depicted than in the advertising of cycles as in the 1880 engraving below ().

Figure 1. Image Source: Heritage Transport Museum, Taoru – Gurgaon, India, online. Previously referenced in Gallagher, Rob (1992) The Rickshaws of Bangladesh, Dhaka: University Press. p.48.

Cycling needs to be understood in and of itself as simply a mode of vehicular transport. There is nothing necessarily inherent in the machinery of cycling to distinguish it from motoring with respect to social equality. While the solo bicycle offered fewer opportunities in use for the exploitation of the labour of others (in its obvious reliance on the tractive power of the rider), the practices of cycling and their occupation of public spaces remained shaped by race, class and gender (see, for example, Finison Citation2014). As an aside, one might also consider here the contrast between artisanal cycle production and the organisation of factory assembly-line mass production pioneered by Pope in the USA. The latter brought about unit cost reduction, and therefore increased affordability, at the cost of the elimination of worker autonomy. It also served to normalise a standardised safety bicycle to the extent that other design possibilities are rendered “other”.

For those sufficiently privileged to be able to access them, early cycling and motoring, even aviation, offered visceral thrills and the promise of even greater emancipation: a sense of freedom from the constraints of normal movement (Mom Citation2014). This potential of liberation from constraint creates, in turn, cycling, motoring and flying as desirable practices. These benefits of mobility persisted beyond individual developments in vehicle design into the eras of mass production and mass participation. Yet the impacts of these mobility practices, socially, environmentally and economically are different and distinct. Mass cycling, mass motoring and mass aviation have differing differential effects and impacts, and it is in the diversity of their effects that we come to understand the varied complexities of mobility regimes.

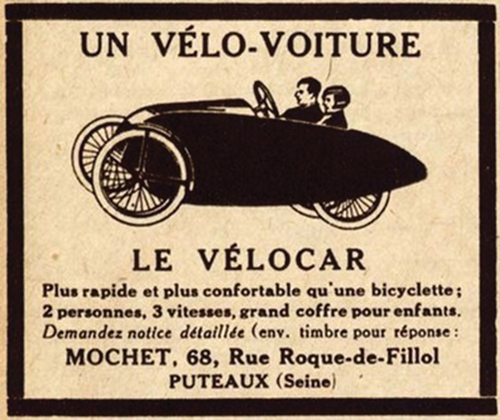

Democratization of mobilities (as a potential for social good) is bound up with the complex meld of materials, spaces and economies that punctuate norms and expectations of gender, class and race in respect of the modes of mobility and their systemic organization. Increased mobility appears to offer benefits beyond the mere capacity to move. Mass affordable motorization, as manufacturer Charles Mochet so eloquently declared, promised democratization: “No-one should doubt that the automobile must become a democratising force … it is a social necessity to put the practical means to overcome the inconvenience of distance within reach of the populace” (Mochet Citation1931 author's translation). Yet the irony of Mochet’s observation is that it was made in the context of a powerful critique of actually existing motoring, its absurd wastefulness of energy and space. Mochet’s favoured solution at this point was his Vélocar: a two-seater, pedal powered vehicle, the forerunner of today’s velomobiles ().Footnote1 It could be fitted with a supplementary motor, but the Vélocar was fundamentally a pedal driven, sociable, quadricycle. The solution to automobilism as populism was to be found in a cyclecar. Ultimately however, as Gorz (Citation[1973] 1980) recognised, when motoring did become possible for the majority, its freedom remained firmly conceptual. Spatial and environmental realities dictated that one could only be free to travel by car if not all availed themselves of this opportunity. The reality of mobility today, nearly a half century on from Gorz’ comments, is that to achieve sustainability in mobility, significant reductions in personal and collective hypermobilities are required in the motorized world (Whitelegg Citation2016). What this means for vélomobility need to be further explored. For the moment, we need to move from critique of automobility to the ways in which its potentials and realities serve to shape vélomobilities, their pasts and futures.

By the 1930s, cycling (at least in Britain) was being constructed in public discourse as the “other” of motoring (Cox Citation2012). Key markers of cycling in the British press of the day, persistent through to the present, are of it as slow, unsafe, vulnerable, low-status, and non-aspirational. All these can be seen as inversions of the status images linked to driving. At one level, a crude, imperialistic Social Darwinism is involved. Cycling becomes the primitive “other” superseded by a more advanced technology (regardless of historical fact). Cycling is thus part of the narrative of automobility, appearing as its precursor, now obsolete and destined to be superseded. This crass narrative masks a more multifaceted set of distinctions between cycling and driving mobilities that add complexity to the relation. Simultaneously, and perhaps somewhat perversely, cycling is also constructed as a bodily elite performance, in contrast to democratic body of the driver. The promises (though not realities) of mass motoring, available to every household, permeate motor advertising materials through the middle and later years of the twentieth century. They are reflected not only in car design but also in a profoundly gendered heteronormativity, made explicit as the car becomes a mirror of domestic space constructed for a nuclear family.

Let us, for the moment, set aside the veracity of these and just recognise their existence as credible and well-circulated mythic discourses. Lots more images are possible as antithesis of driving and we must also set aside the gap between these images and reality/actuality of driving. The task for a future vélomobility, therefore, is to escape from a temptation to usurp automobility simply by refuting the discursive constructions of cycling. Replacing the dominance of the car with the domination of the (bi)cycle may be a welcome change for a reduction of car(bon) emissions and to deal with environmental and spatial pollution, but a post-car vélomobility requires more than a vehicular substitution if it is to confront the other dimensions of automobility identified above.

1.3. Cycling, capital and a circular problem

The crucial problem here is that, as Urry (Citation2004) identifies, the system of automobility has been fundamental to the reproduction of capital through the latter part of the twentieth century and beyond. The growth economy is a high carbon economy. When cycling is presented as a substitute for some journeys – as desirable and absolutely necessary as this is – there remains a risk that cycling augments the technico-political system of automobility. Increasing levels of cycling for some journeys, coupled with a move to e-motoring or hydrogen power for others is a means to sustain the system of automobility, especially its entanglement with growth imaginaries (Liegey and Nelson Citation2020). If cycling is presented as an equal and valid substitute for motoring, then the political relations inherent in automobility remain unchallenged. Whilst the focus on modal shift is on behaviour change, the structural dimensions of the problem remain unchallenged. Even collective changing of practices cannot overturn the systemic dimensions of automobility. In order to challenge automobility’s entanglement with the reproduction of capital in an accumulative (growth) economy, any radical alternative mobility system must simultaneously explore connections to alternative economic paradigms. An encounter with the emergent models of degrowth (D’Alisa et al., Citation2014; Kallis Citation2018) provides fruitful ground for analysis, synchronous with a retreat from hypermobility. As Alexander and Gleeson (2109) show, degrowth is no longer just an economic analytic but one that speaks to urban and suburban planning and practice.

So let us return to the problem and consider how pro-cycling discourses approach the issues of thinking of cycling as a primary mobility mode. I want to note, as one intimately engaged in the policy process, that even radical pro-cycling solutions are often constrained by attention to prosaic detail and the search for credibility. Yet the paradox of much cycling advocacy, whether through political means or framed within a research context (Oosterhuis Citation2019) focuses on technical solutions without reframing the problem in political terms. The conscious aversion in policy persuasion from any perceived threats to automobility (in order to maintain public credibility and in line with economic realism) only increases the resilience of automobility as a dominant regime . When the problem of power relations between mobility modes is considered, then the solution to current asymmetries is to attempt to correct power imbalances through the transfer of power from one mode to another. Taking road space from cars to create cycle lanes is a typical form of this rebalancing. However, what this method fails to do is to consider the more fundamental grounds on which power is developed and held through processes of exclusion and dominance. The hegemonic dimensions of automobility are thus rendered more resilient.

Systemic automobility acts to structure power in an aggressively hierarchical manner. It creates a dominant group. It does so through a binary logic of exclusion, rendering those outside of the dominant as subordinate, of lesser or no value. What commences as a choice between options becomes a binary code of inclusion/exclusion. Relational systems of infrastructures associated with automobilities serve to further reinforce this zero-sum game. (Cass, Schwanen, and Shove Citation2018) The temptation in pursuing a vélomobile future is to replace the dominant group without rethinking the relations of power embedded across mobility practices; in which case vélomobility becomes a means to continue and entrench automobility in a different form, rather than to generate autonomobile futures as means to envisage mobility beyond the car. If vélomobility is to be a mobility system for a degrowth society, then it has to be part of a reframing of mobility itself, not simply the practices.

We have already encountered the difficulties of language in communicating alterity in mobility systems and the same problem confronts us when framing discussions of change. One of the difficulties in thinking through the necessary shift to transformative models is the way we think about change. The vocabulary of revolutionary models (doubly tempting in thinking about cycling – if only for the value of a pun, see Rosen’s 2002 chapter 7 “Up the Vélorution”) is that revolutions can simply invert power hierarchies while leaving the relations of power untouched. Transformative solutions must be linked to more than revolutionary schemas of change. As Finn Mackay (Citation2015, 6) puts it in her discussion of radical feminism: “Feminism is a movement for change, not a changing of the guard. By this, I mean that we are not working for a world unchanged apart from the leadership. Ours is a revolutionary movement, thus it is about a different type of world altogether, one not marked by extremes of poverty and wealth, or by war and exploitation”. Retaining the language of revolutionary change, she draws attention to the vital importance of transformative politics transgressing the apparent bounds of its nominal concern. Hers is not an argument for women’s inclusion in a world marked by other forms of inequalities. A revolutionary or transformative vélomobility needs to be more than just more bikes and more conducive conditions for cycling.

For the argument here, the pertinent question is not which mode is dominant, but how mobility relations are structured in order to reproduce relations of dominance and subordination. Further, in order to break models of change that merely “change the guard”, we need to consider how mobility relations might be reimagined beyond models of “success” based solely on the concentration and accumulation of power. To do so, one can fruitfully look to explorations of the “pluriverse” and an assemblage of radical reinterpretations of being of which degrowth is but one element. Significant for the argument here are the contributions of Boaventura de Sousa Santos (Citation2018) in relation to counter-hegemony. In rethinking the challenge of globalisation in an interdependent and interconnected world, Santos argues not simply for anti-globalisation, which always risks the danger of a retreat into nationalism and isolationism. Instead, the argument is positively made for a counter-hegemonic globalisation, challenging the hegemonic dimensions of existing globalisations and simultaneously reappropriating, détourning and reimagining the ideas and practices of globalisations. This also seeks to challenge the imposition of any singular solution or analysis that would itself create a new hegemony. To counter hegemony is not simply to replace current dominations with another form of domination.

Thus, Santos’ framework presents a set of options to transform the mobility framework without foreclosure. The challenge facing a meaningful articulation of vélomobility as a challenge to automobility should not be underestimated; nor should the urgency of the task. Unless automobility itself is fundamentally challenged, processes that enable the system, regime or dispositif of automobility to adapt undermine any process of real change. To begin to think about vélomobility as autonomobility we need to confront the implications of autonomobility and to begin to create a political imaginary that links cycling to degrowth. Importantly, we need here to think of degrowth in a positive light, not as shrinkage in a growth society. In blunt terms, to insist on the need to reduce distance travelled is not to urge confinement, but to liberate one from the necessity of meaningless travel (Whitelegg Citation2016). Immobility may be perceived as a burden in a hypermobile society, where mobility is seen as a value in itself, but minimal mobility as a chosen path in this situation can also be a form of resistance. Reducing mobility to a human scale politicises it.

Developing this radical transformative approach and building on the longer tradition of post-development critiques of linear ideas of progress (see Sachs Citation1992), Escobar (Citation2020, ix) uses the term pluriversality to highlight how “realities are plural and always in the making” in order to counter the idea that of an opposition between binary options, one real and one possible. Vélomobility or, more properly, vélomobilities, emerge in this argument as more than an alternative to replace automobility (compare Cass, Schwanen, and Shove Citation2018). Instead, they provide alternative perspectives on mobilities, explored in the next section through a series of proposition that should not be read as a point-by-point manifesto, but rather as starting points for further exploration.

2. Part two. Vélomobility as autonomobility

2.1. Starting points

Let me begin my theorisation of vélomobility with a series of propositions and observations. These are designed to highlight that in any consideration of a systemic analysis there are multiple dimensions at play. Rather than produce a static list, or describe the complex as a constellation, one might imagine these as elements within a particularly elaborate orrery.Footnote2 The orrery lays out the relationships of the sun, planets and moons through a mechanically driven model depiction of their orbits. Using this visual analogy draws attention to the nature of the complex interplay between ideas and problems. Rather than being static, as in a graphic depiction, the relations between elements in an orrery are constantly shifting. In this dynamic interplay, some issues briefly come into alignment and connections can be made, but just as soon, they may shift away from each other, and new relationships become visible. A solution may be apt and fitting whilst a certain alignment of events and power is in place but cease to be relevant later. All arrangements of power are necessarily transient and shifting without a single, perfect solution.

What follows is not a definitive series of statements on vélomobility, but a set of propositions intended to provoke debate and interpretation while enabling us to define the contours of our theorisation of vélomobility.

Automobility is a system. Automobility is a closed system. Vélomobility needs to be more than a replication of automobility, therefore vélomobility cannot be a system which excludes other users and uses, it needs to open communications and possibilities. Contrasts can be made with reflexive and open-ended practices. Vélomobility as autonomobility cannot be the inverse of automobility but needs to transform the patterns through which automobility maintains its dominance.

The systemic entanglements of automobility act to generate path-dependence and increase its hegemonic position. Path-dependency maintains power/dominance through the closure of alternative scenarios and possibilities of action. Obduracy is built into the complexity of systemic dominances. Vélomobility cannot therefore be singular, it must take multiple and diverse forms. Vélomobilities must also, necessarily, be fragile and flexible.

To begin to develop a political imaginary of vélomobilities as autonomobilities, in the broader context of a commitment to degrowth within a pluriversal politics requires an unlocking of the creative imagination and an ability to work with both a utopian method and a re-imagination of what is possible and viable. Such a political imaginary needs to be prepared to dream, to go beyond the pragmatic. Older technologies and techniques need to be revisited alongside innovation.

Although critical of social Darwinist evolutionism, vélomobilities are not regressive or counter-innovative. Development and innovation are part of technological play. What is important is that the innovation is accessible and open source, part of a technological commons that facilitates conviviality not alienation.

Practices of vélomobilism comprise multiple elements: material use-objects; material spaces of use; competencies/skills/capacities of users; competencies imparted by spaces of use; meanings imparted by use; meanings generated by the varieties of use of spaces and those imparted to the users by the qualities and affordances of use-spaces. These can be individually analysed but each combination will produce contradictions and tensions. Such multiple practices and experiences produce plural realities that cannot be subsumed into a singular identity or performance. Singular systems of domination eliminate frictions through the imposition of purity of identity and action dependent on the elimination of contestation and diversity.

Defining vélomobilism in its practices as a mode of autonomobility requires us to attend to each of the elements of cycling practice and their constitutive entanglements one with another. Each one needs examining for the degree to which it creates closure, reproduces forms of alienation or moves away from conviviality. Now we also have to have the honesty to recognise that no action is wholly innocent, no element of practice without the possibility of critique. Cycling practices are not a magic bullet and are capable of reproducing existing inequalities and producing new ones of their own.

Transformative proposals for vélomobility as autonomobility need to develop reflexivity, to understand the ways in which particular forms of solutions to problems and which elements of practices (and the ways in which they are structured and interlinked) reproduce the relations of dependence and dominance/subjugation. To imagine that there can be an “ideal” solution is to foreclose the field from contention. There is always a danger here of falling in into the trap of utopia as blueprint. Each technology brings degrees of ambiguity with its introduction and deployment.

To step away from the abstract and ideological dimensions of vélomobility we can illustrate the practical complexity inherent in thinking future vélomobilities, though consideration of a concrete example. Focusing on the practices of vélomobilism described above, we can consider an existing example of design dilemmas and the entanglement of behaviours and material realities; the problems related to increasing efficiency in cycle design, and specifically, the consequences of aerodynamic efficiency.

Approximately 80% of the work required to propel a cycle is used to overcome air resistance, and the power required to overcome air resistance increases as a cube of the speed.Footnote3 Aerodynamic drag increases as the cube of the frontal area of the combined cycle, and other significant elements are drag induced by the form itself. Hence, recumbent cycles (with a smaller frontal area) require less power input than a conventional upright bicycle for the same speed, and a body shell (as used in commercially available velomobiles) will provide about a 50% reduction in the work needed to overcome air resistance.

In practice, this means that for a given power, aerodynamic efficiency (from design innovation) increases speed. Put another way, to maintain the existing speed, less power needs to be input. However, the human body is not controllable in the same manner as a motor: a comfortable cadence (rate of turning legs) and power output cannot just be reduced without inducing discomfort. Therefore, a person put on a more efficient cycle will travel at higher maximum velocities and have different acceleration and deceleration characteristics. Also note that in younger bodies, fitness comes with repeated use and the power output of any given body is therefore also variable, increasing with repeated practice over time.

A range of cyclists with differently able bodies and differently aerodynamically efficient cycles will travel at a variety of velocities and have diverse braking and acceleration characteristics. To maintain cohesion between them, sufficient spaces are required to operate this diversity or conflict will ensue from the different capacities (even without any suggestion that some may be riding for specific fitness gains and thus deliberately aiming for a higher power output). Mitigation might be provided by ruling that only certain designs are allowed within given infrastructures, which then raises questions for inclusion/exclusion. Who should be included/excluded? The problem can also be formulated as one equality versus equity. Is the solution to arrive at the lowest common denominator? Is this viable for a transformative vision of vélomobilities as autonomobility?

Without recognition that speed is not solely a product of bodily effort, faster cycling risks stigmatisation. If cycling is to provide mobility over greater distances, designing for maximum aerodynamic gains is logical in order to minimise the energy required. Speed is also a product of topography, weather conditions and of the quality of space: long straight cycleways produce higher speeds (Cox Citation2019). Speed is more than personal behaviour combined with mechanical and aerodynamic efficiency. In other words, a cycleway is not simply a cycleway: just as there are many kinds of roads we recognise, a regime of vélomobility needs to recognise the many functions and qualities of movement. Thus, there is a concomitant need to rethink spaces of travel as spaces of communication, not just corridors of movement. And that facilitating communication between different types of cycle travel is vital.

Embracing innovation, especially for energy efficiency, may be a necessary part of a more sustainable future, but its implications are ambiguous. To refuse to acknowledge cycle technologies that already exist is absurd but to accommodate the diversity of our material vélomobilities requires more than just technical solutions.

Turning away from this very material discussion of technologies of vélomobility we should return to the theoretical dimensions to the problem of vélomobility as autonomobility in order to explore some opportunities and tools that vélomobilities in line with the propositions above might bring to autonomobility.

2.2. Theorising autonomo-vélomobility

To sum up so far: the transformative capacity of any conceptualisation of mobility is dependent on the sphere of power relations in which it operates. Here I am mainly considering power through the lens of political economic forces, but the wider sets of social power relations with which they are entangled are also relevant. In particular, we need to consider how practices of vélomobilities open up spaces of power through which dominant arrangement can be challenged (Gaventa Citation2021). We need to ask some primary questions in relation to the conceptualisation of alternate systems of mobility (alternate, that is, to the current hegemonic system of automobility).

The primary questions in operation appear to be the following:

What are the sets of power relations that practices of vélomobility change?

What is the scope of its continued dependence on capitalist modes of production and market economics?

To what extent can vélomobility’s performance, and the organisation of that performance operate to maintain non-closure, reflexivity and inclusion?

This paper does not claim profound or complete answers to these problems, but these are directions that our thinking must, potentially at least, travel to explore what a systemic autonomo-vélomobility might encompass. One of the unexpected elements at play in determining answers to these arises from the reflexivity previously mentioned. In the context of cycling research, the academic as actor/agent in late capitalism is in a position not just to observe what vélomobility looks like, but also to act and assist in determining its emergent forms. Put another way, as those engaged in the debates over cycling practices, vélomobilities and autonomobilities, we can decide what forms of power relations we want to see instantiated and reinforced and then shape the systemic discursive structures that will enable them. The academic analyst is not an innocent observer.

This situation that research on alternate and just mobilities finds itself is the opposite of a technology-driven and market-driven process in which the forces of technology and market are released and then the observer waits (“innocently”) to see what happens, trying their best to cope with negative (side-)effects that may result. In the reality of the anthropocene and climate crisis, we now, as agents in the processes of change, move to take control of our direction or we perish.

One should not be so naïve as to imagine that just because one can theorise alternative regimes that capitalist modes of production will vanish or lose their traction. Nor is this a fundamentalist argument they should be, or must be, abolished as a (pre)condition of future progress. Instead, what is important is to consider how existing mobility systems tie us into other systems that we are unable to influence or control. As a means to understand this, one of the most useful models I have found is that of the Gandhian pairing of swaraj and swadeshi as tools in the conceptualisation of change.

Swaraj loosely translates as self-rule or autonomy. Its embrace indicates more than independence since it also declares that a society seeking swaraj has the capacity, social maturity to operate a post-colonial regime, no longer dependent for its survival on the exogenous input of a colonial master. To restate this in the context of automobility raises interesting questions.

The second element, inseparable from swaraj, is swadeshi: self-reliance. There is the obvious material dimension, decreasing dependence on external material inputs. Swadeshi also has a cognitive dimension, reliance on the capacities of local knowledge, of finding solutions appropriate to the specific dimensions of the local experience of any global condition.

Neither swaraj nor swadeshi separate one from the wider context: they cannot be subsumed into a petty nationalism or separatism, because they are formed in the consciousness of an interdependence and a world dominated by a variety of forms of colonialism. Notably, as Ashis Nandy (Citation1983) shows, these are psychic as well as political and material. Autonomo-vélomobility is possible but its realisation requires more theoretical resources than recognisable at first sight.

Before moving on to the interface of vélomobility and autonomobility for the final sections, there is one further dimension arising from automobility that needs to be dealt with for its impact upon and relation to both, and that is a discussion of the role of alienation. An explicitly materialist analysis of alienation provides useful insight into an autonomobile vision of vélomobility specifically as it extends how we might envisage crucial dimensions of vélomobilities as equalities.

People are alienated from the possibilities of the good life that automobility holds out for two primary reasons. First, as Gorz (Citation[1973] 1980) pointed out, it cannot be enjoyed by all. Indeed, its model of “a good life” is intrinsically exclusive – only possible for a minority because of its spatial demands. Second, the cost of automobility’s enjoyment even by a global minority is the destruction of the very planetary life support systems required to maintain human life. It is from that alienation that automobility becomes and remains a prospect of desire (Sachs Citation1984; Galeano Citation2001; Knoflacher Citation2013). While its promises of a good life remain attractive, only within a radically different system of mobility that is available to all, can alienation be overcome.

These observations frame the theorising of vélomobility as autonomobility and perhaps add a further perspective on autonomy from a non-imperial framing. In the above discussions, we now have a set of inter-related grounds and tools for understanding vélomobility as more than a critique or antithesis of a system of automobilities as elucidated by Sachs (Citation1984) or Urry (Citation2005). Rather, vélomobilities invoke plural possibilities of autonomous human-scaled mobilities grounded in self-reliance. The final section of the paper turns to the possibilities that this radical formulation of vélomobility can contribute to discussion of autonomobility when framed within a consideration of mobility justice (Sheller 2018). Three areas are identified, connected in turn to the practices and the materials of vélomobility and to their use implications.

3. Part three. Specific contributions of vélomobility to autonomobility

3.1. Post-anthropocentricism

Humanist rationalism places anthropocentrism at the heart of the world. For Adorno and Horkheimer ([Citation1947] 1997), Bacon’s understanding of technology as the basis of the mastery of nature stands as the start of the process of disenchantment, progressively not just separating humanity but doing so purposefully in “in order to dominate it – to make it and other men calculable, substitutable and, above all, exploitable” (Jeffries Citation2016, 231). To emphasise that this analysis is not unique to the Frankfurt school, a similar conclusion is reached by Bajaj (Citation1988) from a Gandhian perspective. The rationalism of humanism places anthropocentrism at the heart of the world. So, what are the mechanisms for re-enchantment?

Logically, as critical posthumanist analyses such as those of Haraway (Citation2016) or Braidotti (Citation2013) argue, in addition to the cognitive reconnection of the realms sundered by a human/nature divide, there is a more physical dimension required to decentre the human agent. Direct encounter with the more than human world enfleshes thinking in experience. Mobility practices of cycling and walking, based on human bodily performance and unmediated encounter with the physical environment, are an obvious way to assist re-engagement with the visceral and the “other” of weather and climate realities (Vannini Citation2009). More than this, however, in the context of the Anthropocene the deliberate and conscious encounter with that uncontrolled (though not unaffected) by our human action provides a practical site in which we can pay attention to the imposition and inscription of human difference against the reality of indifference of more than human planetary systems (Byrne Citation2020; Rosa Citation2020). In short, vélomobilism provides an affirmative practice that, systemically incorporated, refuses closure or path dependence while demanding reflection on the need and purpose of human travel because of its dependence on the translation of body energetics into movement.

Mobility practices allow us to make spatial shifts, to enact physical dis-location from ties experienced as confining and oppressive. Historically speaking, cycling (vélo-mobile performance as an individualised practice) for women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries enabled its practitioners to escape the watching eye of paternal guardianship and the chaperoned public space. These liberations are what commended it as the vehicle of women’s emancipation. Similarly, the embrace of cycle touring by working class clubs and societies in the same period indicates its potential as a means to re-appropriate space and mobility otherwise denied or maintained only in controlled travel, determined by the employer and master. The history of cycling’s narrative of liberation is thus deeply humanistic and anthropocentric. So on what grounds might we consider vélomobility as a contributor to a post-anthropocentric narrative?

Motorized mobility seized the liberation narrative from cycling and increased its anthropocentric dimensions in the added promise of liberation from bodily work as a cost of movement. Cycling practices strip away that promise and insist on the active dimension of mobility as primary.

The price of movement is paid by the body, not externalised onto invisible others. While there is freedom and thrill, freedom as escape from the immediate worries, these always take place within human limits and it is the bodily human existence of the performer themselves that is primarily at stake in their liberation. Further, this freedom always takes place within the broader realms of social obligation and interaction. The more one escapes immediate ties and obligations, the more one is invisibly tied to ecological realities, either of the planetary systems of day and night and weather, or to the performances of the body itself. Here once again we return to the bodily encounter with the more than human. The context, however, is different from a century ago. Vélomobility as post-automobility is necessarily formed against a background of recognition of automobility’s promises and consequences. A return to travel grounded in renewed visceral experience acknowledges the desensitization possible in enclosed travel modes and self-consciously links the body to the wider rhythms of the planet, seasonal change, climate weather and diurnal rhythms and the constraints that conditions impose on the body. These very constraints are those deliberately overcome by late twentieth century motor travel (in which the SUV even promised to erase constraints of terrain – to free automobility from its systemic medium of the roadscape).

3.2. Breaking dependency chains

Automobility’s promise, and delivery to the end user, of liberation from constraint is paradoxically characterised by upstream chains of dependence upon fuels, infrastructures, systemic production webs. While these complex chains are inevitable in all technologies, they can be shortened.

One often overlooked element of Illich’s analysis of technology is his reflection that convivial technologies are characterised by the degree to which they avoid tying the users into chains of action. Simple machines are simply repaired. They are capable of being built and rebuilt with the minimum of external input. There are no long chains of industrial connections.

As motorisation has been developed over the past century, so the car has become a more and more complex machine, incapable of being home produced and repaired. Contemporary automobility is inconceivable with the automobile technologies of a century ago. In contrast, cycle technologies remain obdurately simple, principally reliant on developments made in the very earliest years of cycle construction. Smart technologies for cycling may have their uses but a system of vélomobility does not depend on their utilisation

“Hi-tech” cycles, cargo bikes, recumbents, velomobiles are no more complicated than conventional bikes, they just rearrange the bits – only the frame differs. Their production is reliant on existing products of the division of labour, but not on the hyperconsumption of consumer materials. The technologies of vélomobility are amenable to shorter, more fragmented production chains, so minimising system entanglement. Indeed, the history of cycling innovation in the last 50 years (Hadland and Lessing Citation2014) is of start-up companies outside the recognised industry, utilising widely available production techniques and materials that exist as by-products of other industrial processes.

A whole range of intermediate vehicle designs operate to provide diversity. Their practical fault line is perhaps the extent to which they provide (and rely on) autonomous mobility, rather than increases of dependency. Thus, human-electric hybrids may be valuable in a way that e-vehicles are not. Of course, there are exceptional cases required for inclusion particularly in relation to the physically mobility-impaired.

3.3. As materialisation of power relations

As Gerbaudo (Citation2017) points out in his discussion of the social implications of technological innovation, what Marx and Engels stressed was that what matters about industrial technology was not just the new forms of production engendered, but the way in which they materialised a relationship of oppression in deployment as in production. For cycling, it is not just the affordances of new forms of technology that are important, but also the social relationships and the ways of life with which they are entangled.

Different cycle designs afford, for example, different energy conversion rates. Returning to and drawing from the example in the previous section, we see that variance of velocity in return for an equal energy input does not just affect individual practices and possibilities of mobility but also realigns forms of interaction. To cope with these changes of interaction through infrastructure requires patterns of regulation and a renewed stress on people and space.

What the cycle ride does is expose one to space. It is possible to cycle in automobile fashion: in other words, to start by demanding the right (and space) to ride. What might it mean to challenge this? To approach the ride as vélomobility is not to embrace a self-denying ordinance but to consider what the journey requires to allow all to participate. Vélomobilities emphasise interaction and conviviality over isolation and competition. This may mean a profound critique of the spatial disadvantage of the vélo-mobile traveller and a responsive demand for infrastructure that does not require reduction to a lowest common denominator of mobility.

Experience of cycling as the slowest and most vulnerable new rider is useful from an educative point of view as an occasional exercise, but deeply impractical as a base mode of mobility, even though it is the driver for a lot of current urban design. What we need to establish is that there is a significant difference between the systematic over-privileging of single group of mobile travellers (under automobility and its echoes) and the provision of mobility-scapes that allow for a variety of forms of use and physical capacities. Vélomobility as proposed here denotes a shift in the relations of travel. Rights-based claims in which conflicting demands are hierarchically arranged inevitably places differing demands as competitors for scarce resources. But mobility resources for travel are only rendered scarce by the current dominance of mobility spaces by powerful and fast-moving vehicles that imperil other multiple and diverse mobility practices. As advocacy groups have pointed out for decades, cycling practices are far less space consuming than car driving. Removing the scarcity by challenging systemic automobility changes the need to hierarchically arrange different needs and inevitably prioritising one group of travellers over another. Power relations of mobility are fundamentally transformed when mobility practices are not competing for a scarce resource.

The power relations of spaces of travel are more than questions over infrastructure design. This problem can also be approached by thinking about space itself as a technology. The affordances of any space are integrally bound up with the affordances of rider and machine, since the three elements comprise a Deleuzian assemblage (Cox Citation2019). Additionally, physical space is complemented by imaginary space. That is, although we need to think about the physical spaces of travel in rethinking mobility, questions of justice require us to step beyond those immediate and obvious parameters to think carefully about how we conceptualise the locations of physical spaces of travel. This is easier to consider by example.

Much of the emphasis on cycling and of the futures of cycling, is posed in terms of cycling’s relevance as an urban solution. Just as we need to ask what is a bicycle, we also need to ask, what is “urban” and why? The divide between urban and rural is a deeply problematic one, with echoes of the divide between metropole and colony. The rural is commonly and often unquestionably posed as “other” to the urban. This should not be surprising since the consolidation of the metropolitan centre occurs at precisely the same historical juncture as the creation of the colony to the centre, (as previously depicted in ).

This conceptualisation is problematic not only for the historically colonial implications but, even today, it renders the non-urban as a problematic other: backward, regressive, incapable of change or of autonomy. Implicitly, only by the incorporation of the non-urban within the urban can the “limitations” of the non-urban be overcome. However, this reproduces colonial policy and analysis. One way of addressing this might be to invert the concentration on urban cycling through revisiting the idea of “rural proofing” especially the arguments addressing rural proofing as socially inclusive design (Rewhorn Citation2019). Rather than the necessity of special provision, good design starts from principles of maximum inclusion. Inclusion thus becomes a core criterion rather than in issue of problem solving that requires consideration of how a core design might be modified to include non-normative others. In practical terms, this requires a shift to understand change as constant, necessary work in progress, rather than the implementation of closed designs replacing one stable, fixed set of structures by another.

Reframing change away from the obsession with universal depictions of best practice increases the processes of inclusion and its limited framing around tightly constructed terms of reference and a heavily normative framing of the ideal subject. To refute the normalcy approach is not to demand a single universal set of criteria, but to engage in reflexive analyses of the impacts of infrastructure and design not only in specific instances but across the systemic provision of mobility spaces and modes, understanding how mobilities are constantly staged (Jensen Ole Citation2014). Good design guides are required but they need to recognise the degrees of diversity and the necessity for future adaptability to unforeseen circumstances.

Vélomobility forces a reconsideration of the power relations of space: not simply road space but the very concepts that underlie the use (and language) of segregation when applied to mobility spaces. Automobility solves cycling as a “problem” by demanding segregation. Vélomobility proceeds by asking how we might end segregation being perceived as a solution.

4. Conclusion

Vélomobility, if it is to be a meaningful concept, can neither invert automobility nor can it simply replace the car. The latter ignores the ways in which automobility is a system of power. Interlocking mechanisms within the system make the car more than an object. The system of automobility demands subservience to its totemic centre: replacing the powerplant of the automobile cannot provide escape from the system. To define vélomobility as the antithesis of automobility is similarly to fail to develop an alternative but only to inherit existing frameworks of relations created by automobility. Cycling practices in such a case will still be defined by automobility and the history of automobilism, shaped within a search for a new hegemony.

This paper has worked to suggest ways of approaching vélomobility as way to explore counter-hegemonic mobilities. It frames future cycling practices not as a mode of mobility within unchanged social and political relations but as a means to rethinking unexamined expectations and assumptions of existing cycling mobilities. Recognising the need to theorise as well as focusing on policy, it eschews solutionism and insists on the importance of values. As a novel perspective, autonomobility provides a means to rethink vélomobility as more than just actions and practices within a system of mobility where cycling is the dominant mode. Rather it provides the opportunity to reimagine vélomobility as an “overt and historically aware political program of research and action” to move past the automobile age (Mattioli et al. Citation2020, 1). Conversely, vélomobility also assists exploration of autonomobility by highlighting lessons learned from prior experience and from the embodied realities of everyday practices.

Vélomobility does more than offer an alternative means to move around the city. It engages with visions of transformative social potential of the critique of both movement and city. It is useful to adapt McDonough’s (Citation2009, 3) analysis of the impact of Situationism on the city into an analysis of vélomobilities’ potential impact on automobility: “[f]rom being the site of alienated labour and passive consumption, the city was reformulated as the locus of a potential reciprocity and community, the crucial spatial stake of any project of radical social transformation”. Under automobility, mobility is a site of alienated labour and passive consumption: vélomobility reformulates mobility practices as the locus of a potential reciprocity and community, and the labour involved can be unalienated, active and agentic. This is both its challenge and potential promise. However, vélomobility as a system does not yet exist. As a mode of analysis, “vélomobility as autonomobility” has to be consciously formed and shaped if it is to fulfil the promise explored here. It is a politics of what is not but what could be.

Bio details if needed

Peter Cox is professor of sociology in the Department of Social and Political Science at the University of Chester UK. His most recent publications are Cycling: A sociology of vélomobility (Abingdon: Routledge 2019) and, with Till Koglin, an edited collection, The Politics of Infrastructure (Bristol: Policy Press, 2019). He chairs the Scientists for Cycling network for the European Cyclists’ Federation and was a founder member of the Cycling and Society Research Group in 2004.

Acknowledgments

I would especially like to thank my colleague Suzanne Francis who commented on an early draft of this paper and to the reviewers whose perceptive and helpful suggestions have pushed my thinking a lot further.

Disclosure statement

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The term velomobile, a direct translation of the Dutch velomobiel, refers to a specific type of cycle, usually with 3 (sometimes 4) wheels, designed integrally with a bodyshell. See www.velomobiel.nl. Vélomobility refers to frameworks of mobility posited in opposition to automobility, usually prioritising cycling and other forms of active travel.

2. Many thanks to Nikki Pugh (Citation2019) for reminding me about the communicative potential of the orrery in her use of it as a means to imagine the journeys of everyday cyclings.

3. These are very loose illustrative figures. The analytical material on cycle aerodynamics is considerable but Wilson and Schmidt (Citation2020) Bicycling Science (4th Edition) is a good starting point.

References

- Adorno, T., and M. Horkheimer. [1947] 1997. Dialectic of Enlightenment. London: Verso.

- Armstrong, A. C. 1946. Bouverie Street to Bowling Green Lane. Fifty-Five Years of Specialized Publishing. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Bajaj, J. K. 1988. “Francis Bacon the First Philosopher of Modern Science: A non-western View.” In Science, Hegemony and Violence: A Requiem for Modernity, edited by A. Nandy, 24–67. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Boaventura de Sousa, S. 2018. The End of the Cognitive Empire. The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Böhm, S., C. Jones, C. Land, and M. Paterson, eds. 2006. Against Automobility. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity.

- Byrne, D. 2020. “Reclamation Legacies.” In Deterritorializing the Future. Heritage In, of and after the Anthropocene, edited by R. Harrison and C. Sterling, 244–265. London: Open Humanities Press.

- Cass, N., and K. Manderscheid. 2010. “Mobility Justice and the Right to Immobility: From Automobility to Autonomobility”, presentation at the American Geographers Meeting, Washington DC

- Cass, N., and K. Manderscheid. 2018. “The Autonomobility System: Mobility Justice and Freedom under Sustainability.” In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, edited by N. Cook and D. Butz, 101–115. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Cass, N., T. Schwanen, and E. Shove. 2018. “Infrastructures, Intersections and Societal Transformations.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 137: 160–167. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.039.

- Cass, N., and K. Manderscheid. 2019. “Call for Papers for Paper for “Shapes of Post-growth Societies”, at the Final Conference of the DFG Research Group ‘Landnahme, Accelearation, Activation’ and the 2nd Regional Conference of the German Sociological Association at the Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany, 23 to 27 September 2019

- Cox, P. 2012. ““A Denial of Our Boasted Civilisation”: Cyclists’ Views on Conflicts over Road Use in Britain, 1926–1935.” Transfers 2 (3): 4–30. doi:10.3167/trans.2012.020302.

- Cox, P. 2014. ”Road Safety and Class Conflict in Britain, 1926-1935.” in Histoire des Transports Et de la Mobilité: Entre Concurrence Modale Et Coordination (de 1918 À Nos Jours), edited by G. Duc; O. Perroux; H. Schiedt and F. Walter., pp. 279–305. Neuchâtel: Editions Alphil.

- Cox, P. 2019. Cycling: A Sociology of Vélomobility. Abingdon: Routledge.

- D’Alisa, G., F. Demaria, and G. Kallis. 2014. Degrowth. A Vocabulary for A New Era. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dennis, K., and J. Urry. 2009. After the Car. Cambridge: Polity.

- Edgerton, D. 2006. The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900. London: Profile.

- Escobar, A. 2020. Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Featherstone, M., N. Thrift, and J. Urry, eds. 2005. Automobilities. London: Sage.

- Finison, L. J. 2014. Boston’s Cycling Craze 1880–1900. A Story of Race, Sport and Society. Amherst: ,University of Massachusetts Press.

- Friss, E. 2015. The Cycling City: Bicycles and Urban America in the 1890s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Furness, Z. 2007. “Critical Mass, Urban Space and Vélomobility.” Mobilities 2 (2): 299–319. doi:10.1080/17450100701381607.

- Galeano, E. 2001. Upside Down: A Primer for the Looking-Glass World. New York: Picador.

- Gaventa, J. 2021. “Linking the Prepositions: Using Power Analysis to Inform Strategies for Social Action.” Journal of Political Power 14 (1): 109–130. doi:10.1080/2158379X.2021.1878409.

- Geels, F. W., R. Kemp, G. Dudley, and G. Lyons, eds. 2012. Automobility in Transition: A socio-technical Analysis of Sustainable Transport. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gerbaudo, P. 2017. “From Cyber-autonomism to cyber-populism.” TripleC 15 (2): 477–489. doi:10.31269/triplec.v15i2.773.

- Gorz, A. [1973] 1980. “The Social Ecology of the Motorcar”. Ecology as Politics, 69–77: London: Pluto Press. Originally in Le Sauvage September-October 1973.

- Haldnand, T., and H. Lessing. 2014. Bicycle Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Haraway, D. J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble Experimental Futures): Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Jeffries, S. 2016. Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School. London: Verso.

- Jensen Ole, B. 2014. Designing Mobilities. Aalborg, DK: Aalborg University Bress.

- Kallis, G. 2018. Degrowth. Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing.

- Knoflacher, H. 2013. Virus Auto: Die Geschichte einer Zerstörer. Wien: Ueberreuter.

- Koglin, T. 2013. Vélomobility – A critical analysis of planning and space PhD thesis, Lund University

- Kothari, A., A. Salleh, A. Escobar, D. Federico, and A. Acosta, eds. 2019. Pluriverse: A post-development Dictionary. Chennai: Tulika.

- Latham, A., and P. Wood. 2015. “Inhabiting Infrastructure: Exploring the Interactional Spaces of Urban Cycling.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47 (2): 300–319. doi:10.1068/a140049p.

- Levitas, R. 2013. Utopia as Method. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Liegey, V., and A. Nelson. 2020. Exploring Degrowth: A Critical Guide. London: Pluto.

- Mackay, F. 2015. Radical Feminism. London: Palgrave.

- Manderschied, K. 2018. “From the Auto-mobile to the Driven Subject? Discursive Assertions of Mobility Futures.” Transfers 8 (1): 24–43. doi:10.3167/TRANS.2018.080104.

- Mattioli, G., C. Roberts, J. K. Steinberger, and A. Brown. 2020. “The Political Economy of Car Dependence: A Systems of Provision Approach.” Energy Research and Social Science 66: 101486. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486.

- McDonough, T. 2009. “Introduction.” In The Situationists and the City, edited by T. McDonough, 1-31. London: Verso.

- McIlvenny, P. 2015. “The Joy of Biking Together: Sharing Everyday Experiences of Vélomobility.” Mobilities 10 (1): 55–82. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.844950.

- Mochet, C., 1931. L'Avenir de la Petite Voiture‟, La Revue des Agents, 1931. In H. Bruning, 1931, l'Avenir de la petite voiture‟, La Revue des agents, 1931, Toulouse: Cepadues-editions, p. 8.

- Mom, G. 2014. Atlantic Automobilism: Emergence and Persistence of the Car, 1895–1940. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Nandy, A. 1983. The Intimate Enemy. Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Oosterhuis, H. 2019. “Entrenched Habit or Fringe Mode: Comparing National Bicycle Policies, Cultures and Histories.” In Invisible Bicycle. Parallel Histories and Different Timelines [Technology and Change in History, Volume 15], edited by T. Männistö-Funk and T. Myllyntaus, 48–97. Leiden: Brill.

- Paterson, M. 2007. Automobile Politics: Ecology and Cultural Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pesses, M. W. 2010. “Automobility, Vélomobility, American Mobility: An Exploration of the Bicycle Tour.” Mobilities 5 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/17450100903435029.

- Pugh, N. 2019. “Orrery for Landscape, Sinew and Serendipity”. Presentation and performance at Cycling and society symposium, Chester, UK: University of Chester 2-3/09/2019 http://www.cyclingandsociety.org/2019-symposium-chester/

- Rewhorn, S. 2019. A Critical Review of Rural Proofing in England. PhD thesis, University Of Chester, UK.

- Rosa, H. 2020. The Uncontrollability of the World. Cambridge: Polity.

- Sachs, W. 1984. For the Love of the Automobile: Looking Back into the History of Our Desires. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sachs, W., ed. 1992. The Development Dictionary. London: Zed.

- Urry, J. 2004. “The “System” of Automobility.” Theory, Culture and Society 21 (4–5): 25–40. doi:10.1177/0263276404046059.

- Vannini, P., ed. 2009. The Cultures of Alternative Mobilities. Routes Less Travelled. Farnham UK: Ashgate.

- Whitelegg, J. 2016. Mobility. Shrewsbury: Straw Barns Press.

- Wilson, D. G., and T. Schmidt. 2020. Bicycling Science. 4th ed. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.