ABSTRACT

This paper addresses the governance of cyber warfare capabilities in the Netherlands. A recent conceptual model of cyberspace is used, which distinguishes between a technical, socio-technical, and governance layer. The issue of cyber warfare governance is addressed through a literature review, interviews, and a partial SWOT analysis. The literature review provides first insight into existing definitions and perceptions of cyber warfare in the international and Dutch context. Second, the main stakeholders regarding cyber warfare in the Netherlands and their governance roles are identified. The interviews provide more detail and enable partial cross-check of the published narrative. A SWOT analysis allows identification of the main challenges (weaknesses) connected to the governance of cyber warfare in the Netherlands and corresponding mitigating factors (opportunities). The research findings show the infancy stage of cyber warfare capabilities and governance in the Netherlands. They testify to the problem of reconciling differing and sometimes conflicting interests, and point to the need for collaboration and unified coordination of governance efforts within the Netherlands. However, governance of national cyber warfare capabilities requires more than a concerted national effort alone. Sensitivity to the international environment is indispensable given the complexity of cyber warfare governance.

Resumen

Este artículo aborda la gobernanza de las capacidades de guerra cibernética en los Países Bajos. Se utiliza un modelo conceptual reciente de ciberespacio que distingue entre una capa técnica, sociotécnica y de gobernanza. El tema de la gobernanza de la guerra cibernética se aborda a través de una revisión de la literatura, entrevistas y un análisis SWOT. La revisión de la literatura proporciona una primera visión de las definiciones y percepciones existentes de la guerra cibernética en el contexto internacional y holandés. En segundo lugar, se identifican los principales stakeholdersen relación con la guerra cibernética en los Países Bajos y sus roles de gobernanza. Las entrevistas proporcionan más detalles y permiten una verificación cruzada parcial de la narrativa publicada. Un análisis SWOT parcial permite la identificación de los principales desafíos (puntos débiles) relacionados con la gobernanza de la guerra cibernética en los Países Bajos y los correspondientes factores atenuantes (oportunidades). Los resultados de la investigación muestran la etapa de infancia de las capacidades y la gobernanza de la guerra cibernética en los Países Bajos. Atestiguan el problema de conciliar intereses divergentes y, en ocasiones, conflictivos, y señalan la necesidad de colaboración y coordinación unificada de los esfuerzos de gobernanza en los Países Bajos. Sin embargo, la gobernanza de las capacidades nacionales de ciberguerra requiere más que un esfuerzo nacional concertado aislado. La sensibilidad al entorno internacional es indispensable dada la complejidad de la gobernanza de la guerra cibernética.

Palabras clave:

Introduction

In July 2016, the NATO Warsaw summit recognized cyberspace as the fifth domain of warfare, next to the land, sea, air, and space domain (Warsaw Summit Communiqué, Citation2016).Footnote1 In September 2014, at the previous NATO summit in Wales, agreement had already been reached to consider cyber defense part and parcel of NATO’s core task of collective defense (Wales Summit Declaration, Citation2014).Footnote2 NATO cyber defense exercises—dubbed ‘Locked Shields’—have been held annually since 2010. Even earlier, in 2008, the Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence was established in Talinn, Estonia (Cyber Defence Exercises, Citation2016; Dijk, Meulendijks, & Absil, Citation2016, p. 67–8).

Cyberattacks on any of the NATO members can now justify invoking Article 5—the alliance’s well-known collective defense clause. But, as of yet, no one knows what kind of cyberattack might actually cause Article 5 to come into effect. And, whether or not offensive actions constitute an integral element of a defensive response (Meyer, Citation2015, p. 47–9; Veenendaal, Kaska, & Brangetto, Citation2016). With little of a cyber doctrine or cyber policy available, any such decision thus depends upon the situation and is in the end decided by the North Atlantic Council on a case-by-case basis (Limnéll & Salonius-Pasternak, Citation2016; Wales Summit Declaration, Citation2014).

This paper is an exploratory investigation into cyber warfare governance from the perspective of the Netherlands, a small and little-mentioned, but not insignificant member of the EU and of NATO. The paper aims to shed light on cyber governance issues in a country not often discussed in the wider literature. It thus offers a relatively unique new insight into the challenges and opportunities faced by similar smaller and/or medium-sized EU and NATO countries making up the numerical bulk of both organizations’ membership. Given the inherent confidentiality of the discussed topic, the lack of benchmarks, and the exploratory stage of cyber warfare activities at this point in time, the conclusions of this investigation can only be considered tentative. Future research incorporating the experience of other countries should therefore be encouraged to further progress in this interesting and relevant field of research.

Exploring the cyber warfare domain

With military activities entering the fifth domain of cyberspace, military cyber capabilities are rapidly developing. These capabilities can be used for defensive, offensive, and intelligence purposes. Cyber capabilities will certainly become part and parcel of conventional military operations and conventional warfare (Defensie cyber strategie, Citation2012). However, although many internationally accepted rules and regulations govern conventional warfare, there is no common international understanding as of yet of what constitutes cyber operations, or cyber warfare for that matter (Mueller, Citation2014).

Many countries choose to apply the laws and regulations governing conventional warfare to cyberspace as well, but the characteristics of this domain are different from the characteristics of the other domains (Mueller, Citation2014). Cyber activities used for malicious purposes can, for instance, remain undetected, and the effects can be less tangible than the effects of conventional military actions. As a result, the lack of clear international rules and regulations could result in miscalculation, misperception, and misunderstanding (Confidence building measures, Citation2014).

In the 2015 revision of its Defence Cyber Strategy, the Dutch government has stated that over the next years the Netherlands will work together with its allies to mitigate the risks of integrating digital cyber capabilities with conventional military operations (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015, p. 1–2). In order to do so, a common understanding is needed on what constitutes cyber warfare and on what rules and regulations apply. This paper provides an overview of the governance challenges and mitigating factors with regard to cyber warfare in the Netherlands in an attempt to answer the following question:

“What are the main governance challenges regarding cyber warfare for the Netherlands, and how can these challenges be mitigated?”

A recent three-layer model by van den Berg is used in order to assess which stakeholders in the Netherlands have a governance role at the technical, socio-technical, and governance layer (van den Berg, Citation2014). A literature review is conducted to obtain more insight into the international definitions used to describe cyber warfare. In addition, an analysis of the weaknesses and opportunities of the Dutch system is offered to ascertain the challenges its stakeholders face in governing cyber warfare. Mitigating factors at each layer are identified as well that can assist in creating a more robust governance framework.

Conceptualizing cyberspace

To comprehend the governance challenges with regard to cyber warfare in the Netherlands, it is necessary to demarcate the notions of governance as well as cyber warfare. In this paper, governance is seen as the establishment of policies, and the continuous monitoring of their implementation, by the members of an organization’s governing body (Governance, Citation2016). The notion of cyber warfare is explored in more detail in Section 4.

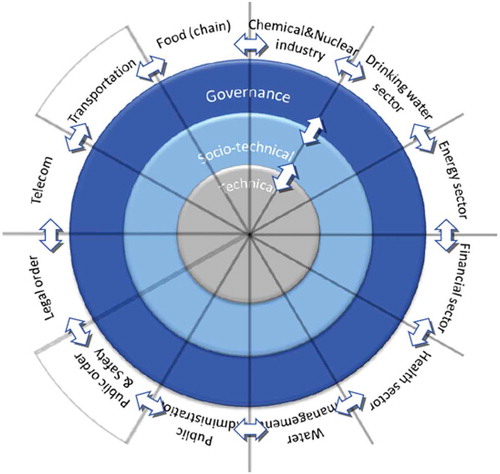

The given explanation of governance has led to an investigation of cyber warfare stakeholders, in this case the members of the governing body of an organization. In order to create a complete picture of those governance stakeholders, and their policies in the realm of cyber warfare, the conceptualization of cyberspace offered by van den Berg (Citation2014) is used. According to this model, cyberspace can be divided into several cyber subdomains and needs to be analyzed on three different layers. See below for a visualization.

Figure 1. Conceptualization of cyberspace.

Source: van den Berg (Citation2014).

Technical, socio-technical, and governance layer

From the model, it follows that cyber warfare is positioned in the cyber subdomain of Public Order & Safety. The model also shows that looking into the technical aspects of cyberspace alone does not suffice. Socio-technical and governance aspects need to be considered as well. The technical layer concerns the more traditional notion of information security (hardware and software, including cables, satellites, routers, codes, etc.), whereas the socio-technical layer concerns the range of cyber activities that people are currently able to perform. These cyber activities consist of the interaction between people and the IT systems available to these people. The governance layer consists of a large number of human actors, organizations, and (supra-)state governing bodies that (try to) regulate cyberspace and—in doing so—influence the technical as well as the socio-technical layer (van den Berg, Citation2014).

Section 4 also provides the results of a literature review of the stakeholders and the policies they establish, implement, and monitor regarding cyber warfare in the Netherlands at each of the layers of the model by van den Berg (Citation2014). The results of the literature review are complemented by interviews conducted with three cyber specialists working for the Ministry of Defence. Given the confidentiality of the subject, these sources wish to remain anonymous.

The following subquestion is addressed:

“Which stakeholders can be identified at the technical, socio-technical, and governance layer that have a role in the establishment, implementation, and monitoring of cyber warfare policy in the Netherlands?”

After determining which stakeholders and what policies apply to the notion of cyber warfare in the Netherlands, a review of the weaknesses and opportunities of the current system is conducted in order to ascertain the obstacles and possibilities that these stakeholders are faced with (see Section 5). Analyzing the results of the review can help disclose the changes and improvements to be made in order to improve the system in place. For the purpose of this paper, the weaknesses and opportunities identified at the technical, socio-technical, and governance layer are used in order to discover the main challenges and mitigating factors regarding cyber warfare. Section 6 provides an overview of the results of the literature review and analysis, providing the main challenges and mitigating factors regarding cyber warfare in the Netherlands.

The information provided in this paper is based on public sources. Three interviews have been conducted with anonymous cyber specialists of the Dutch Ministry of Defence to address some gaps in the publicly available information. Nevertheless, many questions regarding cyber warfare remain and more research in the future is necessary to help provide answers. However, given the confidential nature of cyber capabilities—especially offensive cyber capabilities—many stakeholders have a strategic interest in keeping (parts of) its governance structures and procedures confidential.

Defining cyber warfare and identifying stakeholders

This section outlines the results of the literature review regarding the governance of cyber warfare in the Netherlands. The first part offers insight into the existing definitions of cyber warfare, which serves to show that despite the existing wealth of literature no agreement yet has been reached on notions of cyberspace, cyber warfare, etc. What remains so far is a confusing amalgam of fact and opinions. The second part describes the main stakeholders with regard to cyber warfare in the Netherlands and their governance roles at each of the layers as envisaged by van den Berg (Citation2014) in their conceptualization of cyberspace.

Defining cyber warfare

The literature review shows that there is no common international understanding of what constitutes cyber warfare (Mueller, Citation2014). Notions like cyber espionage, cyberattack, cyber war(fare), and even cybercrime are often conflated. To illustrate the point, in 2014 Singer and Friedman wrote that defining cyberwar need not be complicated. Discussing the key elements of war in cyberspace, they regard them as similar to warfare in other domains. There is always a political goal and mode and always an element of violence. Subsequently, they refer to the US government’s position on the use of force in which a cyberattack results in death, injury, or significant destruction, without exploring the definition issue any further (Singer & Friedman, Citation2014, p. 68; p. 121).

However, a cyberattack is not the equivalent of cyber warfare. In the eyes of Thomas Rid, it first has to be clear whether a cyberattack can actually be characterized as an act of war. To qualify as an act of war, a cyberattack or any offensive cyber act should, according to him, meet three distinctive criteria: (1) it must have the potential to be lethal, (2) it has to be instrumental, and (3) it has to be political. According to Rid, no known cyberattack so far has met all three criteria, and therefore he draws the conclusion that no cyber warfare has ever taken place (Rid, Citation2012).

Although Rid’s extreme position has sparked a fruitful scientific debate, it has not led to an internationally agreed-upon definition of cyber warfare. It could be argued whether this stage will ever be reached. According to the USA Law of War Manual (LOWM), a definition of cyber warfare “often depends on the specific legal context in which it is used” (Law of War Manual, Citation2015). This would preclude a commonly accepted cyber warfare definition. And indeed, a range of definitions can nowadays be found, offered by different authors and/or organizations (Denmark invests in cyber offensive capabilities, Citation2015; France to invest 1 billion euros to update cyber defenses, Citation2014; Law of War Manual, Citation2015; Rid, Citation2012). Some randomly selected cyber warfare definitions in circulation are described below in . These merely serve to illustrate the current confusion and potential misunderstanding when it comes to discussing the concept of cyber warfare.

Table 1. Some examples of cyber warfare definition attempts.

At this point in time, Martin Libicki probably has the most measured analysis to offer on the theme under discussion. He defines cyberspace as the agglomeration of computing devices that are networked to one another and to the outside world. Like any other domain, it is a domain of potential conflict, which can lead to a (cyber)attack, that is, a deliberate disruption or corruption by one state of a system of interest to another state. According to Libicki, cyberattacks can constitute full-scale cyberwar, defined by him as (a) deliberate attack(s) on a network with the aims of paralyzing it (Libicki, Citation2009, p. 6–23). He thereby distinguishes between strategic and operational cyberwars. Strategic cyberwar is made up of cyberattack(s) launched by one entity against a state and its society primarily, but not exclusively, for the purpose of affecting the target states behavior. Operational cyberwar has a more limited scope in his opinion and is defined as the use of a computer network to support physical military operations (Libicki, Citation2009, p. 117).

With all this in mind, the attention will now be turned to the Dutch context. Ducheine and van Haaster (Citation2013) have provided the following hands-on definition of cyber warfare:

“Cyber warfare is the execution of military cyber operations.” (Ducheine & van Haaster, Citation2013, p. 369).

Since this definition speaks of cyber operations, it is necessary to find out what cyber operations entail. The Dutch Defence Cyber Strategy (DDCS) speaks of enabling military operations in the digital domain through (1) defensive, (2) offensive, and (3) intelligence cyber capabilities. The DDCS provides the following distinction of these three concepts (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015):

Offensive cyber capabilities, or digital means that aim to influence or disable the actions of an opponent.

Defensive cyber capabilities, or digital means that aim to protect the effectiveness and deployability of the armed forces.

Intelligence cyber capabilities, or digital means that aim to gather information in order to strengthen the position to judge and influence opportunity, threats, and risks in cyberspace.

The definition and wording used in the DDCS fall in line with an international definition provided by the so-called Tallinn Manual process:

“Cyber operations are the employment of cyber capabilities with the primary purpose of achieving (military) objectives in or by the use of cyberspace” (Schmitt, Citation2013, p. 258).

The DDCS defines offensive cyber capabilities as the availability of digital means with the purpose of influencing or denying enemy action by means of infiltration of computers, networks, and weapon and sensory systems in order to influence information and systems. The Ministry of Defence uses digital means exclusively against military targets (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015). Identifying these targets can only be done with the help of detailed and timely intelligence. Furthermore, the Dutch intelligence law provides the only legal framework so far to conduct offensive cyber activities.Footnote3

Defensive measures are considered equally important to ensure the effectiveness and deployability of the armed forces. During an operation, rapid response might be necessary in case of a cyberattack. Proven attribution through computer network exploitation (intelligence) is essential in this respect. This emphasizes once again the need for evaluated and validated intelligence that need to be provided timely to a commanding officer (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015).

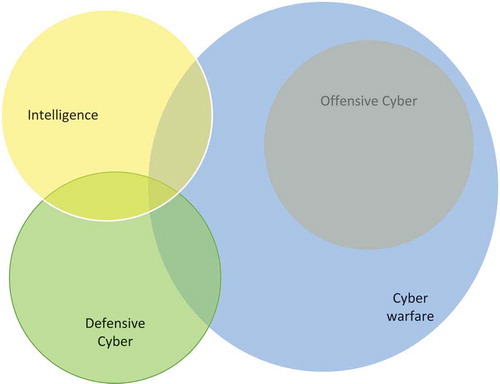

High-quality strategic and operational intelligence is conditional for the execution of military missions. These can be complemented by (locally) acquired intelligence using other means (human, signals intelligence). According to the DDCS, an integral intelligence position enables the Ministry of Defence to properly estimate and influence opportunities, threats and risks (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015). below offers a more detailed overview of defensive, offensive, and intelligence capabilities.

Table 2. Defensive, offensive, and intelligence capabilities from the Dutch perspective.

Stakeholders and governance

The following pages list the results of a literature review of the stakeholders and the policies they have established and are implementing regarding cyber warfare in the Netherlands. The three layers of the model by van den Berg (Citation2014) are used and addressed separately with the following subquestion in mind:

“Which stakeholders can be identified at the technical, socio-technical, and governance layer that have a role in the establishment, monitoring, and implementation of cyber warfare policy in the Netherlands?”

Stakeholders and policies on the technical layer

The technical layer of the conceptualization model concerns the technology and IT (both hardware and software) that enable cyber activities at the socio-technical layer (van den Berg, Citation2014). The focus is on stakeholders that have a role in enabling defensive, offensive, and intelligence cyber capabilities. See below for a description of the Dutch government’s expectations of these cyber capabilities.

Table 3. Dutch government expectations regarding cyber capabilities.

The updated DDCS describes the strategy and requirements needed to obtain these cyber capabilities (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015). Purchasing technology and development of capabilities for defensive and intelligence purposes is not new to the Ministry of Defence. After all, the use of defensive and intelligence capabilities is not solely restricted to cyber warfare. These capabilities contain a diversity of “ordinary” cyber activities, such as office automation.Footnote4 Offensive capabilities, on the other hand, can only be used for cyber warfare activities. See below for a visualization.

Figure 2. Visualization of cyber warfare activity and the three types of cyber capabilities (Courtesy of C. Rugers).

Of relevance here is the fact that the Ministry of Defence has made the strategic decision to obtain cyber capabilities by purchasing technologies through the private sector (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015). The DDCS states that the current processes used to purchase these technologies need to be adapted to match the dynamic character of the digital domain (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015). However, the required adaptation is still in progressFootnote5 and for obvious reasons public sources remain silent on the topic. As a result, the search for sources to identify the stakeholders and policies on the technical layer focuses on current purchasing processes for obtaining regular IT.Footnote6 See and below for the search results.

Table 4. Identified stakeholders on the technical layer with a role in the purchase of resources.

Table 5. Additional stakeholder with a governance role.

The literature review identified two stakeholders operating on the socio-technical layer with a (partial) governance role on the technical layer. See below.

Stakeholders and policies on the socio-technical layer

In order to discover the stakeholders involved in cyber warfare at the socio-technical layer, it is necessary to look at those actors that play a role in conducting cyber warfare and the cyber activity that comes with it. According to Boeke, the Dutch institutional cyber landscape in general resembles a participant-governed network connecting partners on a basis of trust and equality (Boeke, Citation2016, Citation2017, p. 6). Rather than being centralized, cyber capabilities and responsibilities are spread across different organizations—each with their own tasks, interests, and culture. This distributed nature requires much time-consuming and laborious deliberation among the participants and is especially marked within the Ministry of Defence, which is responsible for cyber warfare capabilities in the Netherlands—either for defensive, offensive, or intelligence purposes. The implementation of which, however, is covered by different organizational elements each sharing only limited data with each other (Cyber Warfare, Citation2011; Defensie cyber strategie, Citation2012; Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015; Landschapskaart cyber security, Citation2014).Footnote7

Within the Ministry of Defence, the Defence Cyber Command (DCC), which was formally established in 2014, is a key stakeholder with regard to cyber activities. This includes the development of defensive, offensive, and intelligence capabilities and activities (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015). In 2014 DCC commander General Folmer (current DCC commander) described the DCC as the central entity within the Ministry of Defence for the development and use of military operational and offensive cyber capability. In his view, it is possible to support military operations with cyber capabilities. As a force multiplier, offensive cyber capabilities can increase the effectiveness of the armed forces and become a crucial addition to existing conventional military capabilities (Folmer, Citation2014; Vijver, Citation2017).

However, to become more than a force multiplier on paper and actually support military operations requires the development of capabilities, which in turn draws attention to the available budget. The annual budget of the DCC in 2017 was €22.5 million, divided in investments, exploitation, and personnel (in millions of Euros) (see )Footnote8 —a small amount in the light of a total Dutch Defense budget of about €8 billion, and a minute amount compared to US Cyber Command’s budget as stated at the website of the US Department of Defense, which is expected to rise to $650 million in 2018 out of a total US Defense cyber budget of $7 billion.

Table 6. DCC budget 2012–2018 (in millions of Euros).

The total defense investment budget for cyber (weapons) amounted to €7 million in 2016 and will rise to €9 million from 2017 onward. About 40% of this budget is assigned to the DCC, 40% to the MIVD, and the remaining 20% to Joint Information Provision Command (with the acronym JIVC), the Netherlands Defence Academy (NLDA), and the Directorate of Operations (DOPS).Footnote9

Within the defense organization, the DCC is embedded in the Army Operational Command, although the DCC falls under the direct responsibility of the Dutch commander in chief (Folmer, Citation2014). Its employees include civilian and military personnel from all four operational commands (army, navy, air force, and military police) (Folmer, Citation2014). Given the multilateral and joint character of the DCC, the strong organizational army connection seems peculiar. Two interviewees pointed, for instance, at the DOPS that houses the Joint Special Operations unit (JSO): a long-time cooperation of marines (navy) and commandos (army). Given the clear operational and multilateral character of the DCC right from the outset, they expressed the opinion that a DCC situated within the DOPS would have benefited the expected and required cooperation among the different actors involved.Footnote10

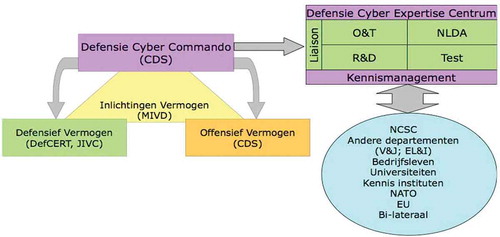

The DCC is obliged and clearly instructed to cooperate closely with the Military Intelligence and Security Service (MIVD) and the Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU)—which is a cooperative endeavor of the Defence Intelligence and Security Service (MIVD) and the General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD). These organizations perform their tasks based upon a separate intelligence and security law. The DCC is explicitly excluded from this legal regime and any offensive cyber operation thus depends upon the capabilities of the MIVD and JSCU. All three organizations are very different in procedures, operating style, tasks, and outlook. Although they find each other in a wish to establish an access position, they may differ severely in the exploitation (in time and approach) of the opportunities obtained. They need to understand each other’s needs and possibilities first, before a common understanding is within reach. However, without the input of the MIVD and JSCU, the DCC is rendered helpless. In addition, the DCC cooperates with a number of other partners inside and outside of the Ministry of Defence (Defensie cyber strategie, Citation2012). An overview of the DCC environment and linkages (in Dutch) is provided in .

Figure 3. DCC environment and linkages (in Dutch; explanation provided underneath).

Source: DCC Ontwerp Organogram (Citation2014).

To achieve its tasks and objectives, the DCC (Defensie Cyber Commando) is divided into three departments: the Technology Department, the Operations Department, and the Cyber Expertise Center (Defensie Cyber Expertise Centrum; DCEC). The development and deployment of offensive cyber capabilities (Offensief Vermogen) is placed in the Technology Department and will consist of cyber specialists with the expertise to act offensively in the cyber domain. However, this capability is currently not operational. Future deployment will be dependent on the expertise developed; the legal possibilities of DCC, MIVD, and JSCU; and the indispensable support of the other two departments within DCC. This also applies to the support of the defensive (Defensief Vermogen) and intelligence (provided by MIVD, JSCU) capabilities of the Ministry of Defence (Folmer, Citation2014).Footnote11

The Operations Department and the Cyber Expertise Center (DCEC) are equally important for the successful execution of cyber capabilities. Within the Operations Department, a pool of cyber advisers will support operational units by advising the commander on the use of digital means, vulnerabilities, and capabilities of the enemy as well as own troops. The cyber advisers are the link between the operational unit in the area of deployment and the cyber units in the Netherlands (DCC and DEFCERT). The Defence Cyber Expertise Center (DCEC) is responsible for strengthening the knowledge position and innovative capability within the cyber domain, and thereby contributes to the strengthening of the three described cyber capabilities. The DCEC cooperates with the National Cybersecurity Centre (NCSC), other ministries (ander departementen), commercial business (bedrijfsleven), universities (universiteiten), (international) knowledge institutions (kennisinstituten), NATO, EU, and by means of bilateral contacts (Bi-lateraal) (Folmer, Citation2014).

The DCC—under direct supervision and control of the commander in chief—represents the proverbial spider in the web, acting as a coordination and operational hub when it comes to Dutch cyber warfare activities. However, the required expertise and (technical) infrastructure to conduct such cyber activities is not present within the DCC, nor does it fall under its span of control. Indispensable partners when it comes to operationalizing and legalizing cyber warfare activities are the MIVD, JSCU, and DMO within the Ministry of Defence (Oratie Ducheine, Citation2016).

The question whether the mentioned stakeholders have a cybersecurity governance responsibility is difficult to answer and depends upon the chosen point of view. In principal, the DCC answers to the commander in chief, whereas the MIVD answers to the secretary-general of the Ministry of Defence. Both in turn answer to the minister of defense. The JSCU is governed by a management board answering to the secretary-general of the Ministry of Defence and the minister of interior affairs (Organisatiestructuur Bestuursstaf, Citation2016; Organogram Defensie, Citation2016).Footnote12

Governance matters, aided by oversight mechanisms and legislation (national and international law), ultimately reside at these top levels. However, cyber is a relatively new and dynamic phenomenon. A mature governance mechanism with a corresponding coherent set of rules, regulations, and protocols is not in place yet. This development process is being fed and thus partly shaped by those developing, implementing, and executing cyber activities on the socio-technical layer. The proposed defense cyber warfare doctrine can serve as an example. Part of long-standing conventional practice, the formulation of a doctrine—that is, authoritative guideline incorporating theoretical considerations and (best) practice—was envisioned from the outset, although it will take at least another year to be published. DCC and MIVD, in particular, and the broader cybersecurity environment, in general, will, by means of such activities, influence the final outcome of the governance structure of Dutch cyber warfare activities (Defensie cyber strategie, Citation2012).

Stakeholders and policies on the governance layer

Identifying stakeholders

van den Berg (Citation2014) describe the governance layer as the layer that governs the technical and the socio-technical layers in complex ways. The results of an investigation into the main stakeholders and policies that govern the cyber warfare activities and the technical means needed to conduct cyber warfare are given below.

As mentioned earlier, the Ministry of Defence considers cyberspace to constitute the fifth domain of military action. In the coming years, the Ministry of Defence will work on developing cyber capabilities to further support its military operations. Consequently, these cyber capabilities can, in the future, be used to support conventional military operations. As such, the legal framework that applies to the use of cyber capabilities is no different than the legal framework that applies to the use of conventional capabilities.Footnote13 This means that, at this point in time, the deployment of cyber capabilities is in line with the procedures for the deployment of conventional military capabilities (Ducheine & Arnold, Citation2015).

The rules and procedures for the deployment of military capabilities regarding conventional warfare are dealt with in constitutional law. Consequently, it is necessary to look at conventional law to find out which actors have a role with regard to the deployment of cyber capabilities. Article 97 of the Dutch constitution proclaims that the armed forces are an instrument of the democratic state. This means that the armed forces are subject to civil authority as represented by the Dutch government. Under conventional law, one of the main stakeholders involved in the decision-making process with regard to the deployment of the armed forces is the Dutch government (Ducheine & Arnold, Citation2015).

The second main stakeholder is the Dutch parliament. Constituting the legislature, the parliament has a number of opportunities to check the actions of the government. This also applies to governmental decision making on deploying the armed forces (Ducheine & Arnold, Citation2015).

Other important stakeholders with regard to military operations can be identified. These include the ministers of defense, foreign affairs, general affairs, and the commander in chief of the armed forces. These stakeholders have an important role to play in the process of agenda setting and decision making with regard to deploying the armed forces. However, due to the concept of “unity of governmental policy,” these stakeholders are not as such recognized within constitutional law (Ducheine & Arnold, Citation2015).

Identifying policies

In order for the above-mentioned stakeholders to make a decision on deploying a cyber operation, they need a legal base. A distinction can be made between national and international legal frameworks that might apply to the deployment of cyber capabilities (Ducheine & Voetelink, Citation2011).

Two national legal frameworks can be identified. First, the Intelligence and Security Services Act provides the legal provisions for the General Intelligence and Security Service and the Defence Intelligence and Security Service. Second, the Police Act 2012 mandates the Dutch military police to investigate and prevent cyberattacks (Politiewet 2012, Citation2012). However, these national frameworks primarily focus on defensive capabilities and law enforcement. As a matter of principle, national legislation does not contain the provisions for offensive military operations. Consequently, it is necessary to look at the international legal frameworks that apply (Ducheine & Voetelink, Citation2011).

International law actually prohibits the transboundary use of force, both offensive and defensive. This is included in article 2(4) of the UN Charter. However, what remains unclear is whether or not the use of offensive cyber capabilities is considered to be “armed force” and as such is prohibited under article 2(4) of the UN Charter. International law does contain three exceptions to article 2(4): assent could be provided by the applicable state, coercive measures as stated in chapter VII of the UN Charter could apply, and self-defense could be necessary (Ducheine & Voetelink, Citation2011).

Once an exception to article 2(4) is invoked, the international laws that regulate war apply. These laws consist of two strands: jus in bello and jus ad bellum. Jus in bello refers to international humanitarian law and includes provisions for the conduct of armed forces when they are engaged in war or armed conflict. Jus ad bellum applies to the conduct of engaging in war or armed conflict including crimes against peace and war of aggression (ICRC, Citation2015). However, the question that remains unanswered is whether or not the laws of war apply to cyber operations, and if so in what manner (Ducheine & Voetelink, Citation2011).

The present international legal frameworks to cyber operations therefore require scrutiny. One initiative that has been set up in order to address this issue is the Tallinn Manual process. This process was initiated by the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE). The CCDCOE tasked an international group of independent international experts to examine how international legal norms apply to the fifth domain of cyber warfare. The Tallinn Manual primarily focuses on the applicability of both the jus ad bellum and jus in bello. The original manual was published in 2013. Tallinn Manual 2.0 has provided an update and extension of the first handbook (Tallinn Manual 2.0, Citation2016). The Tallinn Manual is not an official document, being considered “an expression of the scholarly opinions of a group of independent experts acting solely in their personal capacity” (Schmitt, Citation2013). However, with no official alternative at hand, the manual fulfills current needs and is generally considered good enough to taken as a model at this point in time.

Another initiative was launched by the Organization for Security and Cooperation Europe (OSCE) in 2012. The OSCE invited an Informal Working Group to come up with so-called Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs) for reducing the risk of conflict in cyberspace. The aim of the CBMs is to “enhance interstate co-operation, transparency, predictability, and stability, and to reduce the risks of misperception, escalation, and conflict that may stem from the use of ICTs” (Arnold, Citation2016; OSCE, Citation2013).

Analyzing weaknesses and opportunities

A review of existing weaknesses and opportunities is applied here to identify the challenges and mitigating factors to cyber warfare for each of the three layers (the technical, socio-technical, and governance layer). In order to do so, the identified weaknesses are used to recognize the main challenges with regard to cyber warfare in the Netherlands. The identified opportunities are used to recognize the mitigating factors capable of addressing these challenges.

Technical layer

The results of the analysis for the technical layer are mainly based on information obtained in interviews. Below, the challenges (weaknesses) and the mitigating factors (opportunities) are described for the technical layer.

Weaknesses (challenges)

Currently, there is no legal framework for offensive cyber capabilities (except for missions). The lack of a generally accepted legal framework for the use of offensive cyber capabilities, as discussed in the governance layer, has repercussions for the technical layer. With regard to conventional offensive military operations, conventional law dictates that collateral damage of any operation should be specified before conducting any operation. Given the complex nature of cyberspace, it is, however, very difficult to precisely determine the collateral damage created by technology used for offensive cyber operations.Footnote14 Solving this problem might prove impossible but will certainly affect the full-scale use of technical capabilities and require a lot of time, energy, and innovative brainwork on the technical level.

Another challenge constitutes the Dutch Information Act that applies to purchasing procedures regarding offensive cyber technologies.Footnote15 Consequently, the Ministry of Defence is to disclose all information regarding its purchasing procedures if requested upon. By disclosing this kind of information, adversaries may be given intelligence on the technology bought and used by the Ministry of Defence. This allows adversaries to focus on exploiting weaknesses in this technology in order to obtain a military advantage.

Opportunities (mitigating factors)

The Ministry of Defence is aware of the challenges as stated above and is currently exploring options to address these challenges. The ministry collaborates with the NATO Industry Cyber Partnership and the European Defence Agency for mutual development and purchasing of cyber capabilities (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015). The information obtained though these international partnerships could help the Dutch Ministry of Defence in optimizing its own purchasing processes.

Socio-technical layer

Weaknesses (challenges)

The description of the socio-technical layer has shown several weaknesses. The current organizational structure offers a challenge for the future and may lead to imperfect collaboration or friction given widely differing lines of communication and accountability. On a more generic level, it is clear that the combination of defense, offence, and intelligence is far from a natural partnership since interests and perspectives deviate markedly. Another challenge is posed by the absence of a coordinating body—a role the DCC does not perform—spanning the chain of cyber partners. Finally, the absence of a defense cyber doctrine or related documents such as standard operating procedures (SOPs) or Rules of Engagement (RoE) is a serious weakness. Without authoritative guidelines in place, it is difficult to set a course for the future development of cyber warfare activities.

Opportunities (mitigating factors)

These weaknesses are to some degree counteracted by developments on different stages. A clear opportunity constitutes the fact that cyber appears to be high and rising on the political agenda (Hennis: dreiging cyberspionage tegen Defensie neemt toe, Citation2016; Kamerbrief—Voortgangsrapportage uitvoering Defensie Cyber Strategie, Citation2016). Furthermore, there are concrete initiatives for national and international cooperation on the cyber stage. On the national level, scarce and expensive cyber capacity is being pooled and this trend is supposed to continue. For example, in the foreseeable future, DCC, MIVD, and AIVD will be brought under one roof (Hennis: dreiging cyberspionage tegen Defensie neemt toe, Citation2016). On the international level, cooperation initiatives are present as well, such as the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Talinn, Estonia. Finally, the fact that a Dutch cyber warfare doctrine is currently drafted presents a clear opportunity for the deployment of cyber activities.

Governance layer

Weaknesses (challenges)

International law provides some guidelines for cyber warfare on the governance layer. However, it is unclear whether cyber operations constitute armed force and are thus prohibited under international law. What is more, the question remains whether cyber operations can amount to an armed attack, justifying a response of self-defense by states. Another question is whether a cyber operation has enough “intensity of force” to be labeled as armed conflict or as a “hostility” (Ducheine & Voetelink, Citation2011).

As such, it can be stated that one of the weaknesses, and thus one of the main challenges, with regard to cyber warfare is the extent to which the existing legal frameworks that currently apply to conventional warfare also apply to cyber warfare.

Opportunities (mitigating factors)

One initiative that has been set up in order to address these gaps in international law is the above-mentioned Tallinn Manual process. The Tallinn Manual process primarily focuses on determining the applicability of both the jus ad bellum and jus in bello to the fifth domain of cyber warfare (Tallinn Manual 2.0, Citation2016). Even though the Tallinn Manual is not a legally binding document, it certainly provides a useful framework for creating national legislation and procedures. Other examples include the work done by the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts on cybersecurity and the OSCE efforts to create an international understanding on what constitutes cyber warfare. The OSCE Informal Working Group came up with 11 CBMs for reducing the risk of conflict in cyberspace (Arnold, Citation2016; OSCE, Citation2013). Consequently, it can be stated that on the governance layer, the opportunities, and thus the mitigating factors for the identified challenges are the Tallinn Manual process, UN initiatives, and the CBMs created by the OSCE.

Concluding remarks

The following procedure was followed to answer the main question of this paper: “What are the main governance weaknesses/challenges with regard to cyber warfare for the Netherlands and how can these be mitigated?” First of all, definitions of cyber warfare have been considered. Cyber warfare in the Netherlands is considered to be the execution of military cyber operations through defensive, offensive, and intelligence cyber capabilities. Second, the main stakeholders and their policies have been identified at the technical, socio-technical, and governance layer. Third, weaknesses and opportunities have been identified at each layer in order to discover the main governance challenges and mitigating factors. This exercise resulted in the following findings at each consecutive layer:

Technical layer

The technology needed for cyber warfare will be purchased through the private sector. However, existing purchasing procedures need to be adapted to respond to the dynamic character of the digital domain. Stakeholders that have a role in purchasing regular IT for the Ministry of Defence have been identified to provide some insight into the kind of stakeholders that might play a role in purchasing technology needed for cyber operations.

One challenge on the technical layer affecting offensive cyber capabilities is the virtual impossibility to specify collateral damage of any offensive operation before conducting an operation. The Dutch Information Act is another challenge since it also applies to the purchasing procedures of the Ministry of Defence. The purchase of offensive cyber technologies might thus be disclosed to the benefit of adversaries. Mitigating factors could be the fact that the Ministry of Defence has shown itself to be aware of these challenges and is currently collaborating internationally to obtain cyber capabilities. The knowledge thus obtained could help in optimizing current purchasing processes.

Socio-technical layer

The main stakeholder on the socio-technical layer is the DCC. The DCC is the central entity within the Ministry of Defence for the development and use of military operational and offensive cyber capability. A number of organizational challenges, however, severely limit its effectiveness.

The required expertise and (technical) infrastructure to conduct cyber operations is not present within the DCC, nor does it fall under its span of control. Other challenges include a lack of a mature governance mechanism, the lack of a coordinating body, and the absence of a defense cyber doctrine for the time being. Furthermore, the combination of defensive, offensive, and intelligence capabilities is far from a natural partnership. Mitigating factors include the fact that cyber appears to be high on the political agenda. On the national level, cyber capacity is being pooled, a Dutch cyber warfare doctrine is in the making, while on the international level cooperation is building.

Governance layer

The deployment of cyber capabilities is not different from the procedures for the deployment of conventional military capabilities. As a result, Dutch government and parliament are the two main stakeholders with a role in the deployment of cyber capabilities. The national legal framework focuses exclusively on defensive capabilities. International law therefore needs to be taken into consideration when it comes to offensive capabilities, although it remains to be seen in which way international law is applicable to cyber operations .

One of the mitigating factors to counter this challenge is the Tallinn Manual Process, which examines how the international framework applies to cyber warfare. Other mitigating factors are UN initiatives, such as the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts on cybersecurity and the CBMs that have been established by the OSCE in an effort to reduce the risk of conflict in cyberspace.

In sum

This exploratory investigation has clearly demonstrated the infancy stage of cyber warfare capabilities and governance in the Netherlands. A governance model is still under construction and no doubt subject to adjustments in the foreseeable future. The research results testify to the problem of reconciling differing and sometimes conflicting interests between, for instance, the DCC and the intelligence community, or the Ministry of Defence and commercial organizations. This indicates the need for collaboration and unified coordination of governance efforts within the Netherlands. Last, the findings highlight the fact that governance of national cyber warfare capabilities need more than a concerted national effort alone. Sensitivity and awareness of developments within the international environment are required in order to address the complexity of cyber warfare governance with any confidence.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank L. Durand, C. Rugers, and R. de Vries for their invaluable input. The input of two anonymous reviewers has been much appreciated.

Notes

1 The Warsaw Summit Communiqué stated: “Cyber attacks present a clear challenge to the security of the Alliance and could be as harmful to modern societies as a conventional attack. …. Now, in Warsaw, we reaffirm NATO’s defensive mandate, and recognize cyberspace as a domain of operations in which NATO must defend itself as effectively as it does in the air, on land, and at sea.”

2 The Wales Summit Declaration stated: “Cyber attacks can reach a threshold that threatens national and Euro-Atlantic prosperity, security, and stability. Their impact could be as harmful to modern societies as a conventional attack. We affirm therefore that cyber defence is part of NATO’s core task of collective defence. A decision as to when a cyber attack would lead to the invocation of Article 5 would be taken by the North Atlantic Council on a case-by-case basis.”

3 Based upon interviews with two anonymous cyber specialists at the Ministry of Defence, March 21 and 23, 2016.

4 Based upon an interview with an anonymous ICT specialist at the Ministry of Defence, March 16, 2016.

5 Ibid.

6 The development on purchased technology is called “rapid tool development” (Hennis-Plasschaert, Citation2015).

7 The cyber environment scan of Nederland ICT (Landschapskaart cyber security, Citation2014) lists 7 government departments with a (partial) responsibility in formulating cyber policies and 44 actors, both public and private, involved in the formulation and/or implementation of cyber activities. Only the Ministry of Defence is tasked with cyber warfare activities.

8 Dutch parliament: Rijksbegroting 2015 Defensie, Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 2014–2015, 34 000 X, nr. 1, pp. 96, 100–101. Recently, the annual defense budget was increased substantially. How this exactly will translate into the defense cyber budget remains to be seen.

10 According to two anonymous cyber specialists at the Ministry of Defence, e-mail correspondence (March 21, 2016) and interview (March 23, 2016).

11 Ibid.

12 Based upon an interview with an anonymous ICT specialist at the Ministry of Defence, March 16, 2016.

13 Dutch parliament: Kamerstukken Parlement II 2013–14, 33 321, nr.3, blz.3.

14 Based upon an interview with an anonymous ICT specialist at the Ministry of Defence, March 16, 2016.

15 Ibid.

References

- Algemene Beveiligingseisen voor Defensieopdrachten 2006. (2006). Ministerie van defensie. Retrieved from https://www.defensie.nl/binaries/defensie/documenten/beleidsnota-s/2006/08/13/abdo-2006/abdo-2006.pdf

- Arnold, K. (2016). Cyber Confidence-Building Measures. Ten stumbling blocks which complicate the development and implementation of worldwide politically acceptable cyber confidence-building measures. Master thesis Leiden University.

- Beleidsregel veiligheidsonderzoeken Defensie. (2013). Retrieved from https://www.defensie.nl/documenten/richtlijnen/2013/10/21/beleidsregel-veiligheidsonderzoeken-defensie

- Besluit Voorschrift Informatiebeveiliging Rijksdienst Bijzondere Informatie 2013 (VIRBI 2013). (2013). Retrieved from http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0033507/2013-06-01

- Boeke, S. (2016). First responder or last resort? The role of the ministry of defence in national cyber crisis management in four European countries. Leiden: Leiden University.

- Boeke, S. (2017). National cyber crisis management. Different European approaches. Governance, 1–16.

- Clarke, R., & Knake, R. K. (2010). Cyber war. The next threat to national security and what to do about it. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Confidence building measures to enhance cybersecurity in focus at OSCE meeting in Vienna. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jun/02/we-need-cyberwar-treaty

- Cartwright, J. E. (2010). Joint terminology for cyberspace operations. Washington DC: USA Department of Defense.

- Cyber Defence Exercises. (2016). Retrieved from http://ccdcoe.com/event/cyber-defence-exercises.html

- Cyber Warfare. (2011). Adviesraad internationale vraagstukken (AIV) No 77/Commissie van advies inzake volkenrechtelijke vraagstukken (CAVV) No 22 (pp. 1–18). The Hague: AIV

- Cyberwar. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/cyberwar?q=cyber+war

- DCC Budget. (2014). Retrieved from https://blog.cyberwar.nl/wpcontent/uploads/2014/10/defensie-budget-cyber-2015.png

- DCC Ontwerp Organogram. (2014). Retrieved from https://blog.cyberwar.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/dcc-ontwerp-organogram-2011.png

- Defensie cyber strategie. (2012). Ministerie van defensie. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/brochures/2012/06/27/brochure-defensie-cyber-strategie

- Denmark invests in cyber offensive capabilities. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.defenceiq.com/cyber-defence/articles/denmark-invests-in-cyber-offensive-capabilities/

- Dijk, A., Meulendijks, B., & Absil, F. (2016). Lessons learned from NATO’s cyber defence exercise locked shields 2015. Militaire Spectator, 185(2), 65–74.

- Ducheine, P. A. L., & Arnold, K. (2015). Besluitvorming bij cyberoperaties. Militaire Spectator, 184(2), 56–70.

- Ducheine, P. A. L., & van Haaster, J. (2013). Cyber operaties en militair vermogen. Militaire Spectator, 182(9), 368–387.

- Ducheine, P. A. L., & Voetelink, J. E. D. (2011). Cyberoperaties : Naar een juridisch raamwerk. Militaire Spectator, 180(6), 273–286.

- Folmer, H. (2014). Het Defensie Cyber Commando, een nieuwe operationele capaciteit. Magazine Nationale Veiligheid En Crisisbeheersing, 12(5), 36–37.

- France to invest 1 billion euros to update cyber defences. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/france-cyberdefence-idUSL5N0LC21G20140207

- Governance. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/governance.html

- Hennis: dreiging cyberspionage tegen Defensie neemt toe. (2016). de Volkskrant. Retrieved from http://www.volkskrant.nl/media/hennis-dreiging-cyberspionage-tegen-defensie-neemt-toe~a4263755

- Hennis-Plasschaert, J. A. (2014). Kamerbrief over offensieve cybercapaciteit defensie. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2014/03/17/kamerbrief-over-offensieve-cybercapaciteit-defensie

- Hennis-Plasschaert, J. A. (2015). Kamerbrief - actualisering defensie cyber strategie. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/kamerstukken/2015/02/23/kamerbrief-over-actualisering-defensie-cyber-strategie/kamerbrief-over-actualisering-defensie-cyber-strategie.pdf

- Informatiebeveiliging. (n.d.). Ministerie van binnenlandse zaken en koninkrijkrelaties. Retrieved from https://www.aivd.nl/onderwerpen/informatiebeveiliging/inhoud/beveiligingsproducten

- Kamerbrief - Voortgangsrapportage uitvoering Defensie Cyber Strategie. (2016). Ministerie van defensie. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2016/03/15/kamerbrief-over-de-uitvoering-defensie-cyber-strategie

- Landschapskaart cyber security. (2014). Nederland ICT. Retrieved from www.nederlandict.nl/Files/ICT/Cyber_Landschapskaart.pdf

- Law of War Manual. (2015). Office of general counsel ministry of defence. Retrieved from http://www.defence.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/Law-of-War-Manual-June-2015.pdf

- Let’s make IT happen!. (2014). Ministerie van defensie. The Hague: Ministry of Defence.

- Libicki, M. C. (2009). Cyberdeterrence and cyberwar. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Limnéll, J., & Salonius-Pasternak, C. (2016). Challenge for NATO – Cyber Article 5. Stockholm: The Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies, Swedish Defense University.

- Meyer, P. (2015). Seizing the diplomatic initiative to control cyber conflict. The Washington Quarterly, 38(2), 47–61. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2015.1064709

- Mueller, B. (2014). Why we need a cyberwar treaty. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jun/02/we-need-cyberwar-treaty

- National Strategic Framework for Cyberspace Security. (2013). Retrieved from https://www.enisa.europa.eu/activities/Resilience-and-CIIP/national-cyber-security-strategies-ncsss/national-strategic-framework-for-cyberspace-security/at_download/file

- Oratie Ducheine. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.defensie.nl/binaries/defensie/documenten/toespraken/2016/01/28/oratie-prof.-dr.-paul-ducheine/oratietekst-ducheine-20160127-gesproken-www.pdf

- Organisatiestructuur Bestuursstaf. (2016). Ministerie van defensie. Retrieved March 30, 2016, from https://www.defensie.nl/organisatie/bestuursstaf/inhoud/organisatiestructuur

- Organogram Defensie. (2016). Ministerie van defensie. Retrieved March 30, 2016, from https://www.defensie.nl/overdefensie/inhoud/organogram

- OSCE. (2013). Permanent council decision no. 1106. Retrieved from http://www.osce.org/pc/109168

- Politiewet 2012. (2012). Ministerie van veiligheid en justitie. Retrieved from http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0031788/2015-07-01

- Regeling Wet bescherming persoonsgegevens ministerie van Defensie. (2009). Ministerie van defensie. Retrieved from http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0026257/2009-09-01

- Rid, T. (2012). Cyber War will not take place. Journal of Strategic Studies, 35(1), 5–32. doi:10.1080/01402390.2011.608939

- Schmitt, M. N. (ed). (2013). Tallinn manual on the international law applicable to cyber warfare. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Singer, P. W., & Friedman, A. (2014). Cybersecurity and cyberwar: What everyone needs to know. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Tallinn Manual 2.0. (2016). Retrieved from https://ccdcoe.org/research.html

- van den Berg, J. (2014). On (the Emergence of) cyber security science and its challenges for cyber security education. NATO STO/IST-122 Symposium in Tallin, (c), 1–10.

- Veenendaal, M., Kaska, K., & Brangetto, P. (2016). Is NATO ready to cross the rubicon on cyber defence? Talinn, Estonia: Cyber Policy Brief NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence.

- Vijver, H. (2017). Deterrence in cyberspace. An analysis of the deterrent use of the Netherlands’ offensive cyber capabilities. Unpublished Master Thesis Netherlands Defence Academy, Breda, The Netherlands.

- Wales Summit Declaration. (2014). Wales summit declaration. Issued by the heads of state and government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic council in wales. Retrieved from http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112964.htm

- Warsaw Summit Communiqué. (2016). Warsaw summit communiqué. Issued by the heads of state and government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic council in warsaw 8–9 July 2016. Retrieved from http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm

- ICRC. (2015). What are jus ad bellum and jus in bello? Retrieved from https://www.icrc.org/en/document/what-are-jus-ad-bellum-and-jus-bello-0

- Willson, D., & Tomhave, B. (2012). Legal & ethical considerations of offensive cyber-operations? David Willson, Attorney at Law (p. 30).

- Zakendoen met Defensie. (n.d.). Ministerie van defensie. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/ministerie-van-defensie/inhoud/contact/zakendoen-met-defensie