ABSTRACT

The relationship of the intelligence services with openness has been elusive and erratic, changing at the path of the scandals that shaked politics and public opinion. At different rhythms and marked by their national contexts, different intelligence services have embarked over the last two decades in different initiatives to promote societal awareness and a better understanding among society on the intelligence function. In this paper, a theoretical framework is proposed for understanding those openness strategies implemented by the intelligence agencies. The paper discusses two potential approaches to openness with a spectrum of mixed approaches in-between them. The first consists of generating and maintaining a (good) image/reputation and, the second is to legitimize its existence and its role within the State.

1. Introduction

Associating the intelligence services with concepts such as ‘openness’ and ‘transparency’ has been neither common in the past, nor is it typical today. It therefore comes as no surprise that they are also known as the ‘secret services,’ both in democratic as in non-democratic regimes. However, while authoritarian governments have scant regard for public opinion, accountability in democratic regimes is one of the fundamental pillars for legitimizing and maintaining the legitimacy of their actions.

We believe that the longstanding relationship that in democratic regimes intelligence services have been developing with secrecy and, consequently, their degree of openness and transparency toward society and other key political institutions has passed through three separate phases, each of which characterized by a specific crisis. Those crises played the role of making evident an imbalance between, on the one hand, the unquestionable need for secrecy to carry out intelligence work and, on the other, the requirements for both transparency and accountability that are of concern to any democracy (Farson & Phythian, Citation2011; Gill, Citation1994; Lustgarten & Leigh, Citation1994; Matei & Halladay, Citation2019).

This initial phase covered the three first decades of the Cold War, throughout which the generic and abusive recourse to the clause on ‘national security’ permitted intelligence agencies to cast a shroud over many of their activities. Revelations of large-scale spying cases – which even encroached on the lives of the parliamentarians themselves – reflected a need for better in-depth information on what the intelligence services were up to. Various commissions of inquiry – perhaps the most relevant was the McDonald Royal Commission of Inquiry (1981) in Canada–, highlighted dysfunctional aspects of the system and the need to establish, among other elements, parliamentary control over the intelligence services.

The second crisis extended from public knowledge of the scandals concerning the abuses of those agencies in the nineteen-seventies up until the fall of the Berlin wall. This second phase sought to normalize the world of intelligence through an increase in procedures for the declassification of documents, assignation of ministers with responsibility for those agencies, increased parliamentary control and its expansion, and the inclusion of intelligence studies in university curricula. It is therefore no surprise that a sound intelligence expert such as Hulnick Citation1999awould affirm in those years that ‘dealing with the public is as much a function of intelligence these days as the recruiting of agents or the forecasting of future events.’ That policy of Open Government that pervaded other areas of the public sector at the time meant that Ken Robertson would distrustfully ask in 1999, in reference to the world of intelligence, ‘Why governments want you to know?’

The present crisis of the intelligence services in relation to secrecy came after 9/11. The massive and visible irruption of the intelligence agencies into public life increased after the terrorist attacks at the heart of European cities (Madrid, Paris, and Brussels). This intense day-to-day presence and their increased surveillance capabilities with its potential to affect privacy in our Western-style liberal democracies – as the leaks orchestrated by Snowden made clear–, meant that the intelligence services had to enlarge the explanations on their activities and the limits of their powers. This greater demand for transparency and control has meant that [for democracies] ‘the days of the Cold War ‘secret state’ have given way to those of ‘the protecting state’ and their intelligence communities will have to reflect that in their relationships with the public’ (Omand, Citation2012, p.156).

Every crisis meant the beginning of a new phase in the relationship between the intelligence services and its environment. Some of the measures and the initiatives adopted to show openness and transparency were tactical and others meant a change in the behavior of the intelligence agencies. Whether to forget their recent past in some countries, as political police, and to justify their new role in a nascent democracy, or whether to defend their role in the war against terror and to justify the mass surveillance campaigns monitoring public activity, the authors have not identified any theoretical framework that could give support, understanding and address to those changes and others that could be initiated by other intelligence services.

These openness initiatives have two possible goals: either to improve the image and enhance the reputation of the service or to establish and maintain the legitimacy of their actions and, according to each case, even of their own existence. Both reputation and legitimacy are, in our view, key and have impact on the practical conduction of intelligence activities. For instance, the capability of attracting and recruiting the best talent with the necessary and appropriate knowledge, skills and abilities for the intelligence workforce, is widely mediated by images on intelligence organizations as attractive employers and career paths. Tapping the expertise of outsiders for analytic purposes – intelligence policies on analytic outreach and intelligence reserves (Arcos, Citation2013a) – will be influenced by ‘intelligence brand’ aspects such as trustworthiness and reputation. But also, the need of openness is deeper in our days due to security threats like information warfare, foreign interference and hybrid threats where societies and citizens are not mere passive actors and a stronger engagement and understanding is requested from them (Ivan, Chiru, & Arcos, Citation2021).

This article presents a theoretical analysis of the elements and interrelations among them that would help to analyze the openness strategies that some intelligence services have developed over the last years, and at the same time to be used as a guideline to design these strategies for those services willing to be more open. This framework pretends to be valid either to fully developed democracies that have had to adapt themselves to the demands of the fight against terrorism, or to those regimes in transition toward democracy that have had to reconvert their intelligence structures and to adapt them to a non-authoritarian context.

2. Political culture, legitimacy, image, and reputation

A conceptualization of the strategy of openness – also known as ‘intelligence culture’ in some countries – implies understanding, in the first place, what the intelligence agencies seek with this – apparent or real – openness (Lund, Citation2019; Willmetts, Citation2019). Some concepts from political science might be of help for this. In the first place, we have political culture. Almond and Verba (Citation1963) contributed this concept in order to refer to a particular distribution of individual attitudes toward the political system and political objectives among the members of a State. The political culture connects two levels of the political system, resulting from both the collective history and from the personal experiences of the individuals that integrate a specific community over a certain period. The roots of each specific manifestation of the political culture would exist in public events, in the past history of the institutions, and in the micro history of each of its members (Pye, Citation1965, p. 8).

In its individual dimension, Almond and Verba spoke of the existence, in the first place, of an area of subjectivity; in other words, the focus of political culture would not be on the formal or informal structures of politics and its interrelations, but on what the people think and feel about them. This focus, as Verba (Citation1965, p. 516) pointed out, does not have to be what effectively happens in the real world; something that is very appropriate when we are talking of the world of intelligence services. On the other hand, there would have to be an element of perception in the political culture, because we start on the basis that the individuals are not responding in a direct and mechanical way to the stimuli that they receive, but they do so through certain mental schemes, predispositions, and attitudes. The response of the individual will therefore be the result of subjective reflections, having experienced objective situations. In third place, there would be individual attitudes – internalized aspects of objects and relations – that respond to the way in which the psychological relation appears between subject and object; that is, the subject relates to the political object in a cognitive and evaluative manner.

Linked to this individual dimension of the political culture is the concept of legitimacy. As professor Morlino indicated, legitimization is a set of positive attitudes with respect to State institutions that are considered the most appropriate for the governance of a country (Morlino, Citation2003, p. 118). Some years earlier, Linz had made reference to efficacy and to effectiveness, to understand the formation of legitimacy and its continuation (Linz, Citation1978, p. 40). These variables can change over time, depending in large measure on the behavior and functional operation of the institutions; in any case, the relations between them would neither be transitive nor linear, given that perceptions of both efficacy and effectiveness tend to be biased by the initial commitment toward their legitimacy. In other words, legitimacy, at least for a time, operates as a constant positive that multiplies any positive value that efficacy and effectiveness can achieve. Sensu contrario, if the legitimacy of an intelligence agency is, for example, negative, because of its ties to an authoritarian regime or scandals due to mass surveillance, those failures of efficacy and effectiveness will reduce their legitimacy even further. As a result, the more positive the values of each of the relations between legitimacy, efficacy, and effectiveness over time, the greater the stability and performance of the political regime in question. In short, all the actions of openness that these agencies undertake will reinforce their legitimacy and, as a result, will strengthen democracy.

Finally, it is the concept of reputation that is very often synonymous with image. Reputation is linked to the assessment, the opinion, and the appraisal that someone develops with regard to something and, as such, it is supported by perceptions. However, while some authors place the accent on reputation as a perceptive event (and not necessarily factual in its totality) (Dowling & Pfeffer, Citation1975), others accentuate the experiential nature (Gotsi & Wilson, Citation2001); in other words, strictly linked to experience – on the part of the stakeholders – with the product or service that the organization supplies to them.Footnote1 Reputation and image cannot be directly managed through isolated messages and a strategy is therefore necessary where the behavior of the organization has great relevance (Fombrun, Citation1996).

Public Relations models (Grunin & Hunt, Citation1984) can help in clarifying – regardless of specific actions – which classic avenues can generate this (good) reputation that we will find in the theoretical framework proposed in this article. The ‘press agentry model’ has publicity as its objective, with communication flowing in one direction: from the sender to the receiver, where the truth is at times sacrificed. The second, the ‘public information model,’ is also a one-way model, from the sender to the recipient; but in which the important aspect is to transmit information or a message. The ‘two-way asymmetric model’ is used with the objective of not only informing, but also of persuading, so that the stakeholder accepts the point of view of the organization and supports its behavioral patterns. Finally, there is the ‘two-way symmetric model,’ or excellence model, where both parties are open to letting themselves be persuaded by the reasoning of the other and to introducing changes in search of common benefits. Grunig and White (Citation1992, p. 55) developed the argument that ‘public relations cannot be excellent if organizations have a culture that is authoritarian, manipulative, and controlling of others–asymmetrical in its worldview of relationships with others.’ However, mixed forms of these models can also be found when organizations practice public relations with their publics/stakeholders.

In summary, an organization has to comply with the social expectations associated with a majority of the population for it to gain legitimacy, while reputation would be linked more to the attitudes and feelings of the different stakeholders toward an object, organizations and institutions (Deephouse & Carter, Citation2005; Bromley, Citation1993; Ruef & Scott, Citation1998). Thus, while legitimacy is an essential element for the survival of an organization, reputation concerns the evaluation of an organization that is already seen to be legitimate (Fombrun, Citation1996; Heil & Whittaker, Citation2011; King & Whetten, Citation2008).

Organizations with high cognitive legitimacy – those supported by a rational evaluation of what the organization is – may perhaps lack media coverage or have very little, given that they are not subject to questioning or, in other words, their legitimacy is a given assumption (Deephouse & Carter, Citation2005). Our case differs, because the starting point is not the existence or absence of legitimacy, but it is precisely that the individual members of the general public – principally, although inclusive of stakeholders – are unclear about the identification between their own democratic values and the objectives and the resources that the intelligence agencies employ (Del-Real & Díaz-Fernández, Citation2021). Therefore, the intelligence culture would be very close to the management of what Bordieu (Citation1979) referred to as ‘social capital’; a construct in which image, reputation, and reputations describe the same thing; which, as Verba (Citation1965) pointed out, is what the people think, believe, and feel about those organizations and their role within the democratic system.

If those agencies are either embarking on a campaign to promote their reputation and image or on a more complex search for legitimization it is something not covered by this article which aim is to provide a theoretical framework that can be of help for strategy-making, planning and conducting openness campaigns. All in all, reputation will be the result not only of symbolic interactions, with public information targeting a range of stakeholders, but also of behavioral communications. That is to say, of how intelligence organizations behave when accomplishing their mission. Hutton, Goodman, Alexander, & Genest, Citation2001, p. 258) have argued that reputation as a concept is ‘far more relevant to people who have no direct ties to an organization, whereas relationships are far more relevant to people who are direct stakeholders of the organization […] a reputation is generally something an organization has with strangers, but a relationship is generally something an organization has with its friends and associates.’ Signaling solidness and determination when accomplishing their mission is also an important factor of deterrence. The perceptions about security and intelligence agencies from hostile and criminal actors can deter or prevent adversaries from conducting malign activities and hence reputational capital is an important asset for intelligence organizations that will affect directly or indirectly their performance. Trust and prestige are also key assets involved in direct relationships with allies and foreign intelligence partners, and in joint activities with other domestic intelligence and security services.

For the purpose of gaining a better understanding on communication management by intelligence organizations, it is useful to keep in mind the distinction between grand strategy, strategy, and tactics, developed by Carl Botan (Citation2006). Accordingly, ‘grand strategy is the policy-level decisions an organization makes about goals, alignments, ethics, and relationship with publics and other forces in its environment,’ while strategy refers to ‘the campaign-level decision-making involving manoeuvring and arranging resources and arguments to carry out organizational organizational grand strategies’ (Botan, Citation2006). This author identified four generic grand strategies ‘based on major differences in organizational goals and on attitudes toward change, publics, issues, communication, and public relations practitioners’; the four grand strategies are: intransigent, resistant, cooperative, and integrative.

At one extreme of the spectrum, intransigent grand strategy ‘assumes that the group or organization can be autonomous and should seek to impose its decisions on the environment,’ while on the other extreme, the integrative grand strategic approach ‘seeks to integrate the organization into an ever-evolving web of relationships in order to make the organization fully a part of its environment’ (Botan, Citation2006). In the case of intelligence services, depending on whether they are serving the strategic goals of authoritarian states or, on the contrary, the security, liberties, rights, and interest of fully fledged democracies, intelligence agencies can be argued to have developed and passed through extreme forms of intransigent grand strategy to cooperative ones. However, the 21st century threats landscape and security challenges ahead and current, probably require the adoption of integrative approaches accompanying whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches for addressing security threats.

3. Elements of the strategy of openness for the agencies

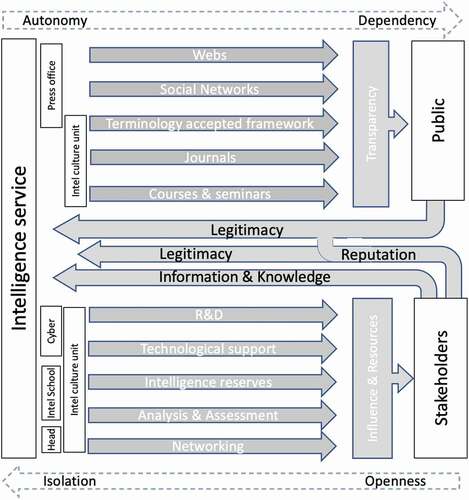

Assuming that each agency will employ the strategy of openness that we present to either one end or the other, and that they can even be mixed, this section develops on how we understand that this strategy would function at a practical level, without – we insist – attempting to assess how it is currently – or could be – employed by different intelligence services. In , the interactions depicted represent those that in our understanding are established between the service and the different actors that constitutes its external world and through which it wishes to obtain either reputation or legitimacy. We have turned to the Theory of Organization in order to construct those interactions between the public and stakeholders; specifically, Institutional Theory (Selznick, Citation1949), the Contingency Theory (Woodward, Citation1958), the Resource Dependency Theory (Thompson, Citation1967), and the New Institutionalism (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). Likewise, we made use of the concepts of reputational management, public relations, institutional image, corporate image and marketing applied to the public sector (Luoma-aho, Olkkonen, & Lähteenmäki, Citation2013).

Figure 1. Interactions between intelligence services and the exterior world.

Understanding both the techniques and the interconnected channels is to understand the two opposing forces that are generated between any organization and its external surroundings, because no organization – including an intelligence service – exists in a vacuum (Selznick, Citation1949). The first point of tension is between Autonomy and Dependence. If the organization decides not to open itself to the environment, it will have greater independence, as it will be able to control what is known about it. However, although secrecy enshrouds intelligence agencies more than other organizations, if they are to survive and remain competitive, they must also emerge from isolation, by importing resources from their external surroundings that will help them respond to the challenges that they face (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978). The second point of tension is, in turn, both the consequence and the source of the first and occurs between Isolation and Openness. With regard to any other aspiration, the organization always seeks to create and to maintain an environment that is negotiated where the future is predictable (Cyret & March, Citation1963); in other words, that stores up the least possible uncertainty. Uncertainty is ‘the relative difference between the amount of information that the organization needs and the amount that is available to it’ (Galbraith, Citation1993, p. 637) and reflects the degree of conflict that exists between different actors (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978). Therefore, as uncertainty can lead to crisis, any organization – as happened following 9/11 and the change in the external panorama–, will make an effort to reduce it.

The different elements included in are detailed below.

3.1 Departments/Units responsible

Besides the director of the agency, two previous studies identified the interfaces through which agencies communicate with the outside world (Díaz-Fernández, Citation2014, Citation2017). Some of those are classic and well-known organizational structures, such as the Press Office or the Institutional Relations Unit. Other interfaces are assuming a role in opening up toward the exterior, such as the Training Schools, the National Intelligence Universities and the Cybersecurity Centers. All of them have undergone a process of opening up, incorporating experts from other areas and providing services and assessment that has increased their visibility in the eyes of some stakeholders. The work that is done through the directors and their Institutional Relations Units may also be relied upon, in order to act as formal interfaces of the agency toward the external world. And, finally, coinciding with this new communication strategy, the most recent units that have seen the light of day are the so-called ‘Intelligence Culture’ Units. In , the elements that appear in are listed and will be detailed in the following sections.

Table 1. Detailed list (non-exhaustive) of potential exchanges between agencies’ units and the external world

At first sight, the function of the above-mentioned units would fall into the classic concept of Public Relations, as an executive function and ‘a strategic communication process that builds mutually beneficial relationships between organizations and their publics’ (PRSA, Citation2012). In other words, to show how the agency is toward the exterior, in order to build and maintain relationship with their stakeholder environment, lead the narrative about the organization in the public discourse, shape attitudes and opinions about the agency, promote and to maintain a good reputation (Grunig & Hunt, Citation1984, p. 8; Cutlip, Center, & Broom, Citation2001, p. 37). However, those units would also help executives to remain one step ahead of the changes and to use them in effective ways, considering them as an early warning system to anticipate future trends (Harlow, Citation1976, p. 36); that is to say, it would help with the preparation of a strategy in relation with the environment. This functionality would precisely be the one which, in our opinion, would distinguish them from the communications departments that lack that executive function, meaning that they act more as interfaces with the external environment rather than as directors and creators of strategy.

3.2 Targeted stakeholders

The broader external environment of an intelligence agency consists of the public. We might define it here by following a totally inclusive definition as general public or ‘a population defined by geographical, community, political jurisdiction, or other limits’ (Allport, Citation1937, p. 8; Price, Citation1992, p. 35); trying to be more specific, the general public would be the citizens to which ultimately intelligence agencies serve by providing intelligence to policy-makers, as well as of other key stakeholders like law enforcement and security agencies, political decision-makers, foreign intelligence agencies, the news media and, evidently, also by those agents that threaten the State.

Even if individual members of the public represent as a set the largest portion of that external environment, intelligence agencies’ interactions with individual citizens, unlike the case of other kinds of organizations, will necessarily be limited for multiple reasons: the members of those agencies work under cover, they have in some cases no recognizable physical installations or that can be visited, and it is unusual for some family member or relatives to admit to be employed in those organizations. As a consequence, the public is expected to do little than just being mere recipients of the messages emitted by the intelligence agency or indirect beneficiaries of the service that the intelligence agencies provide to their government customers. Without doubt, members of the public can exchange information between each other or try to influence each other, for example, through social media networks and offline communication channels; however, at the individual level, their impact will be minimal and mostly ‘mediated’ by news media outlets reporting news stories on intelligence services and eventually providing analysis and opinion on intelligence issues, and hence shaping attitudes and opinions of other actors (Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990).

This difficulty of communicating in a direct and active way with the general public means that intelligence services’ stakeholders assume an important role. As indicated earlier on, the stakeholders could be defined either as a public who are affected by the activity of the organization or whose decisions and behaviors affect or can affect the organization. The concept of stakeholder covers at present many more actors than are in the business world to whom Freeman, Citation1984 first referred in 1984. The most relevant stakeholders for the intelligence agencies would be academics, the political and institutional actors, the business world, the cultural world, and the communications media, as well as the public administrations at different levels (local, national, international), and other foreign and domestic intelligence organizations.

3.3 What the organization produces

From a communication’s perspective, practitioners and associations differentiate between outputs, out-takes (which we are not using in this article for the sake of simplicity), outcomes, and long-term impact.Footnote2 According to the AMEC’s Integrated Evaluation Framework, outputs are what the organizations ‘put out that is received’ by target publics/stakeholders (i.e., information), out-takes are ‘what audiences do with and take out of’ as a result of the organization communication (i.e., attention, recall understanding), outcomes are the effects that the organizations’ communications have on audiences (i.e., learning/knowledge, trust) while impact is ‘the ultimate flow-on results related to your objectives which your communication achieved or contributed to’ and can include among others, reputation, relationships, or social change.Footnote3

Directors and those most senior members of intelligence organizations provide the classified output to policymakers and other intelligence customers according to the services’ mission through a range of analytic products. Beside these mission-oriented outputs, intelligence agencies can employ a range of techniques for communicating and managing relations with their stakeholders. The techniques employed by the intelligence agency should be ideal, to generate the outputs and to disseminate their assessments on a wide spectrum of activities and actors (Deephouse, Bundy, Tost, & Suchman, Citation2016; Díaz-Fernández, Citation2014, Citation2017).

In our opinion, the techniques/tactics at the hands of the agencies are diverse and rather specific for each type of targeted stakeholder. Some of these tools are mission-oriented and information-based as stated above (classified analyses and assessments, briefings, specialized information), unclassified information and public released reports disseminated through owned online channels (websites), press releases, access to internal information sources or unclassified in-house publications. Similarly, communication activities may include participation under different source attribution formulas (i.e. on the record, off the record, background) in journalistic features or depth reporting on security issues, collaboration with investigations, doctoral theses, books … which permit – for instance, academics and media outlets – to obtain with the approval of the organization non-classified information through access to either executives of the service or ex-agents (Blistène, Citation2021).

Other techniques may involve funding opportunities, such as funding research projects (Díaz-Fernández & Del-Real, Citation2018a, Citation2018b), organization of in-house training courses and events, external training, or participation of staff in academic events. Participation in networks and meetings – and not only in news media – provide access to networks and the normalization of the presence of members of the services, outside their everyday routines, at fora, projects, expert networks … The third group of techniques will be of more technical character, such as access of firms to prototypes, data, software, testing and validation or demonstration and validation of cybersecurity providers, training … that would lead to improvements in products and capabilities such as, for example, cybersecurity-related solutions.

In putting out information and engaging stakeholders, the channels used may be official websites, social media accounts, and specialized journals. Not all the services owned or make use of these channels in the same extent, but it is uncommon to find an intelligence agency without at least a website; however, the depth and relevance of the information it contains is a different issue (McLoughlin, Ward, & Lomas, Citation2020).

3.5 What results from the organization’s output and overall impact

Intelligence agencies have to generate transparency, influence, and resources, if want to build on their legitimacy and reputation. There is a direct relation between communicative transparency and organizational transparency in the achievement of their relations of trust with the stakeholders and how they would define their success or their decline as organizations (Auger, Citation2014; Bitektine, Citation2011; Rawlins, Citation2008). Transparency transmits authenticity, trust, and credibility to members of the public, helping in return to strengthen the (good) reputation and to favor a climate so that at times they contribute information to the intelligence agencies. In fact, Hulnick (Citation1999b) was quite right when he suggested that:

a certain level of aura and mystery is necessary in an agency that carries out espionage and secret operations […] but misperceptions about intelligence may be costly, especially when an agency needs public support. Openness has its limits in secret intelligence, but intelligence managers ought to plan for what those limits should be. Being public about secret intelligence may be just as important in a democratic society as being secret about it.

For the specific case of the public sector, transparency has been defined as ‘the availability of information on an actor that permits other actors to control the activity and the efforts of the former (Meijer, Citation2013: 430).’ The problem arises when facing a very institutionalized organization with outputs that are difficult to evaluate (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), as happens in the case of the intelligence services. In those agencies, output is exclusively seen by a small number of political decision-makers with no possibility of the rest of society accessing them. The public – and the great majority of stakeholders – are unaware of it and can only perceive it through intelligence failings, but on rare occasions through their successes. The dimensions of political culture that can be evaluated and assessed are therefore more limited and complex in the case of State intelligence. Therefore, an informed public opinion, an academic community with a more accurate portray of the role of the intelligence services produced via the development of the intelligence studies would facilitate, for example, ordinary citizens to better frame the news and information received from the media and the social networks; it would also facilitate university students to apply for jobs in the intelligence agency with a more solid and robust knowledge of the missions carried out by them. Business community will be also better informed on intelligence issues and more aware of the threats posed by, for example, economic espionage.

Together with transparency, another impact of the activities of the intelligence services is influence. Influence is the capability to modify or reinforce the perception that others have of a situation. Others who will, in consequence, act in the way that one desires; thereby increasing the power of the influencer (Pfeffer, Citation1992, p. 29–31). Nevertheless, in the case of the openness initiatives, the aim is to influence the views that stakeholders hold of the intelligence agency, whether they are pursuing reputation or legitimacy.

Finally, we would have the resources that could be material or immaterial, although we understand that the material resources are in a majority. It is through the funding of projects and seminars, available to technicians and experts, and the development of pilot studies, among others, that a transference takes places from the service to key stakeholders. This will allow some stakeholders – but potentially citizens as well – to increase their awareness on cyber threats and strength the protection of public information and the information networks. Without such activities, some of the core activities of the stakeholders would be very limited.

Similarly, analytic outreach activities can result in the creation of intelligence reserves, groups of practitioners and academics with subject-matter expertise for providing assessments and alternative perspectives in a systematic manner or, in case of necessity, to respond either to eventual crises or to events that are unknown to the agency that has insufficient resources to cover them. As we have previously argued the effectiveness of analytic outreach policies of intelligence organizations and communities widely depends on the capability of building and managing bidirectional trust between the intelligence community and outsiders (Arcos, Citation2013b).

4. Strategies for the intelligence agencies for managing the organizational environment: the management of change

Regardless of whether the intelligence services are searching for either (good) reputation and image or for legitimacy, it is important to understand that openness and the subsequent reception of resources from the exterior will come at a price: the actors in the external surroundings will insist that accounts be rendered. One of the important questions to be solved by the intelligence agency at the time to delineate its road map is which will be the type of strategy they will follow in order to keep on the path to the different stakeholders they will involve in their strategy. On that premise, the reaction of the services would be understandable, attempting to control this increasing interdependence and exchange that is generated with the external world (Selznick, Citation1949, p. 10; Galbraith, Citation1993, p. 626).

The keys on how this controlled management of openness could take place are given to us by Thompson (Citation1967, p. 35). From a lesser to a greater degree of commitment, he related three types of strategies that the intelligence services can also employ: contracting, co-opting, and coalition. In themselves, those types of relations imply neither dominion nor intensity, because – in Thompson’s words – the ‘structural characteristics of the external world’ will define how conflictive or interdependent all these relations will be. We understand that these ‘structural characteristics of the external world’ can be systematized as follows:

(1) Degree of availability of critical resources for an organization

The relation of dependency (power) between whoever supplies resources and whoever receives them is determined by three factors: a) the importance of the resource; b) the degree of discretion that is exercised to obtain it; and, c) the concentration of the resources, which is to say, whether others can also provide it (Emerson, Citation1962; Thompson, Citation1967). More specifically, the existence and the intensity of the power relation comes either from possession, and control over access and use, or from the capacity to intervene in the preparation of norms that regulate possession, use, and distribution of the resources.

(2) Degree of concentration of power and authority in the external world of an organization

The greater the centrality of an organization in the network, the more power and influence it will exercise over other organizations in its area (Cook, Citation1977, p. 72; Davis & Powell, Citation1992, p. 323). The elements that these organizations exchange with the external world, as we have seen, are: a) transparency; b) influence; and, c) resources that are – in our case – in the hands of the intelligence agency. Their dominant (and almost monopolistic) position with regard to some resources, means that intense control may be exercised over the actors at the periphery of the network who wish its centralized nature to continue unchanged.

(3) Degree of interconnection between organizations

The intelligence agencies prefer an asymmetric power relation that modulates the behavior of the different actors in the environment (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978). For the same motive, they will try to ensure that the relations are of a dyadic type, as Georg Simmel theorized; that is, solely one-on-one, between the service and the external actor. In that way, the service can treat each actor in a different manner and can generate two groups: the included and the excluded. The monopoly and centrality of an intelligence agency, linked to the search for dyadic relations, will be the philosophy at the foundation of its control strategy. Upon that strategy, the tactics that it would have available, to exercise its power, would be: a) to reduce the value of the exchange with some peripheral actor; b) to revalue the resource of a peripheral actor, which would confer a more relevant status upon that actor; and, c) to seek out new actors, to increase their numbers, and to generate new alliances, altering the distribution of power within the network.

The different actors are aware that their positions in the network are dependent on good harmony with the central node (the agency), because their knowledge and interrelation with the other nodes is scarce or inexistent. As they have a close relation, they individually can try to influence the central node; however, in view of the difference of relative weight, it is expected that the impact of the actor on the central node will be of little influence. Nevertheless, despite that situation, as the Theory of Social Exchange states, mere permanence in the network produces a value that is beyond any concrete exchanges that take place (Emerson, Citation1962).

5. Conclusions

Openness initiatives consists of activities and actions that are directed toward citizens and stakeholders, encompassing in a generic way reputation management, public and institutional relations. They can, however, pursue and achieve two different objectives through the use of those same strategies and tactics. On the one hand, they can improve the image and the reputation of the intelligence service in society and among some stakeholders and, on the other hand, they can increase and strengthen the legitimacy that the service has within the State apparatus. It would perhaps be recommendable to make use of the two terms ‘reputation management’ and ‘socialization’ instead of the so-called ‘intelligence culture’ used by some intelligence services, i.e., Spanish, Portuguese. Whatever will be the label we give to these initiatives, the modification of that country political culture in relation to the intelligence agencies is the very target of those actions.

Even assuming that the cognitive, affective, and evaluative attitudes toward political culture are not immutable, they do show an accentuated persistence over time, which means that their modification necessarily occurs in a gradual manner. Therefore, although we might, in the short term, confuse the impact generated by the management of reputation and image, in the long term only a process of political socialization will have a significant influence on the legitimization of intelligence agencies and, as a consequence, modify the political culture of a specific country.

Another of the differences occurs at an internal level. Openness and interaction generate effects both on the organization and on its external world. At one extreme, we find ourselves facing the limited permeability of the organization (Scott, Citation2003, p. 96) and, on the other, the external world will finally enter into the organization, even going so far as to modify the organizational objectives (Gouldner, Citation1954, p. 39). In other words, as these initiatives evolve we should verify whether the agencies are showing a new reality to the external world, born in their interior, simply because they themselves would have experienced a change. If it were so, we would therefore face a process of dialogue between the institution and its publics through which the organization would manifest its identity, what it does, and how it communicates with the outside world. Expressed in other words, and drawing on Dolphin (Citation2000, p. 42), this openness strategy would be ‘the process that translates the identity into image.’

The challenge for future investigations resides, therefore, in identifying which of the two approaches an intelligence service has chosen – or perhaps a hybrid one – and, besides, in measuring the solidity and stability of their reputation and legitimacy in society. There are some notable investigations on the management of reputation and intangibles within the Public Sector (Luoma-aho et al., Citation2013) and legitimacy in law-enforcement organizations (Jackson & Bradford, Citation2010; Tyler & Fagan, Citation2008), however, a specific theoretical development is still necessary to be able to adapt them to the case of the intelligence services.

Acknowledgments

This publication and research have been partially granted by INDESS (Research University Institute for Sustainable Social Development), University of Cadiz, Spain.

We would like to thank prof. Rafael Martínez (University of Barcelona) for his inputs to break through one of the dead ends and Dr. Damien Van Puyvelde (University of Glasgow) and Dr. Cristina Del-Real (Leiden University) for their valuable comments on previous versions of this article as well as the reviewers of a more primitive version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Antonio M. Díaz-Fernández

Antonio M. Díaz-Fernández (Cadiz, 1971) is Associate Professor of Criminal Law and Criminology at the University of Cadiz (Spain) where he teaches Criminology and Security. A Member of INDESS (Instituto Universitario para el Desarrollo Social Sostenible), University of Cadiz, Spain. He is deputy editor of The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs.

Rubén Arcos

Rubén Arcos (Madrid, 1977) is a senior lecturer in communication sciences at University Rey Juan Carlos. He currently serves as program Co-Chair of the Intelligence Studies Section at the International Studies association (ISA). He is deputy editor of The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs.

Notes

1. The stakeholders could be defined as the public who are affected by the activity of the organization or whose decisions and conduct might affect the organization.

2. AMEC, Integrated Evaluation Framework.

3. See: https://amecorg.com/amecframework/framework/interactive-framework [Accessed 2nd November 2021] See also: https://amecorg.com/amecframework/home/supporting-material/taxonomy/

References

- Allport, F. H. (1937). Toward a science of public opinion. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 1(1), 7–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/265034

- Almond, G., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture. political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400874569

- Arcos, R. ‘Trusted relationships management as an intelligence function’, in Proceedings of the XVIII International Conference Intelligence in the Knowledge Society, edited by T. Stefan & I. Dumitru. Bucharest: ‘Mihai Viteazul’ National Intelligence Academy, (2013b): 61–74.

- Arcos, R. (2013a). Academics as strategic stakeholders of intelligence organizations: A view from Spain. International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 26(2), 332–346. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2013.757997

- Ashforth, B. E., & Gibbs, B. W. (1990). The double-edge of organizational legitimation. Organization Science, 1(2), 177–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.2.177

- Auger, G. A. (2014). Trust me, trust me not: An experimental analysis of the effect of transparency on organizations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(4), 325–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2014.908722

- Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 151–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0382

- Blistène, P. (2021). Ordinary lives behind extraordinary occupations: On the uses of Rubicon for a social history of American intelligence. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 34(5), 739–760. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2021.1892592

- Bordieu, P. (1979). La distinction. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

- Botan, C. (2006). Grand Strategy, Strategy, and Tactics in Public Relations. In C. Botan & V. Hazleton (Eds.), Public Relations Theory II (Kindle Edition., pp. 223–248). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bromley, D. B. (1993). Reputation, image, and impression management. Chichester: United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cook, K. S. (1977). Exchange and power in networks of interorganizational networks. The Sociological Quarterly, 18(1), 62–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1977.tb02162.x

- Cutlip, S. M., Center, A., & Broom, G. M. (2001). Relaciones públicas eficaces. Barcelona: Gestión.

- Cyret, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs. N.J.: Prentice Hall.

- Davis, G. F., & Powell, W. W. (1992). Organization-environment relations. In M. Dunnette & M. H. Laetta (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 321–326). Palo Alto, Ca.: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Deephouse, D. L., Bundy, J., Tost, L. P., & Suchman, M. C. (2016). Organizational legitimacy: Six key questions. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. Lawrence, & R. Meyer (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (2 ed., pp. 1–42). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

- Deephouse, D. L., & Carter, S. M. (2005). An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. Journal of Management Studies, 42(2), 329–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00499.x

- Del-Real, C., & Díaz-Fernández, A. M. (2021). Public knowledge of intelligence agencies among university students in Spain. Intelligence and National Security, 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2021.1983984

- Díaz-Fernández, A. M., & Del-Real, C. (2018a). Spies and security: Assessing the impact of animated videos on intelligence services in school children. Comunicar, 26(56), 81–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.3916/C56-2018-08

- Díaz-Fernández, A. M., & Del-Real, C. (2018b). The animated video as a tool for political socialization on the intelligence services. Communication & Society, 31(1), 281–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.15581/003.31.3.281-297

- Díaz-Fernández, A. M. (2014). Informes de control de los Comités de Inteligencia parlamentarios como una fuente para la investigación. Inteligencia y Seguridad. Revista de Análisis y Prospectiva, 16, 13–44.

- Díaz-Fernández, A. M. (2017). De secretos a discretos: La política de apertura de los servicios de inteligencia occidentales. In R. Martínez Ed Ed., Comunicación política en seguridad y defensa (pp. 1–25). Barcelona: Cidob.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Dolphin, R. R. (2000). The fundamentals of corporate communication. London: Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-4186-9.50012-7

- Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behaviour. Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1388226

- Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27(1), 31–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2089716

- Farson, S., & Phythian, M. (eds.). (2011). Commissions of inquiry and national security: comparative approaches. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International.

- Fombrun, C. J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman.

- Galbraith, J. (1993). Designing complex organizations. Reading: Addison-Wesley. 1973.

- Gill, P. (1994). Policing politics. security intelligence and the liberal democratic state. London: Frank Cass.

- Gotsi, M., & Wilson, A. M. (2001). Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 6(1), 24–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280110381189

- Gouldner, A. W. (1954). Patterns of industrial bureaucracy: A case study of modern factory administration. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co.

- Grunig, J. E., & Hunt, T. (1984). Managing public relations. Fort Worth: Holt, Rinehart and Wilson.

- Grunig, J. E., & White, J. (1992). The effect of worldviews on public relations theory and practice. In J. E. Grunig, D. M. Dozier, W. P. Ehling, L. A. Grunig, F. C. Repper, & J. White (Eds.), Excellence in public relations and communication management (reprinted 2008 by Routledge Kindle Edition., pp. 31–64). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Harlow, R. F. (1976). Building a Public Relations Definition. Public Relations Review, 2(4), 34–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(76)80022-7

- Heil, D., & Whittaker, L. (2011). What is reputation really? Corporate Reputation Review, 14(4), 262–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2011.20

- Hulnick, A. S. (1999a). Openness: Being public about secret intelligence. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 12(4), 463–483. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/088506099305007

- Hulnick, A. S. (1999b). Fixing the spy machine: Preparing american intelligence for the twenty-first century. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Hutton, J. G., Goodman, M. B., Alexander, J. B., & Genest, C. M. (2001). Reputation management: The new face of corporate public relations? Public Relations Review, 27(3), 247–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(01)00085-6

- Ivan, C., Chiru, I., & Arcos, R. (2021). A whole of society intelligence approach: Critical reassessment of the tools and means used to counter information warfare in the digital age. Intelligence and National Security, 36(4), 495–511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2021.1893072

- Jackson, J., & Bradford, B. (2010). What is trust and confidence in the Police? Policing, 4(3), 241–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paq020

- King, B. G., & Whetten, A. D. (2008). Rethinking the relationship between reputation and legitimacy: A social actor conceptualization. Corporate Reputation Review, 11(3), 192–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2008.16

- Linz, J. (1978). The breakdown of democratic regimes: crisis, breakdown, and reequilibration. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lund, P. K. (2019). Three concepts of intelligence communication: Awareness, advice or co-production? Intelligence and National Security, 34(3), 317–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2019.1553371

- Luoma-aho, V., Olkkonen, L., & Lähteenmäki, M. (2013). Expectation management for public sector organizations. Public Relations Review, 39(3), 248–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.02.006

- Lustgarten, L., & Leigh, I. (1994). In from the cold: National security and parliamentary democracy. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Matei, F. C., & Halladay, C. (eds.). (2019). The conduct of intelligence in democracies: Processes, practices, cultures. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

- McLoughlin, L., Ward, S., & Lomas, D. W. B. (2020). Hello, world’: GCHQ, Twitter and social media engagement. Intelligence and National Security, 35(2), 233–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2020.1713434

- Meijer, A. (2013). Understanding the complex dynamics of transparency. Public Administration Review, 73(4), 429–439. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12032

- Morlino, L. (2003). Democrazie e Democratizzazioni. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Omand, D. (2012). Into the future: A comment on agrell and warner. Intelligence and National Security, 27(1), 154–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2012.621610

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. (1978). The external control of organizations. New York: Harper and Row.

- Pfeffer, J. (1992). Managing with power: Politics and influence in organizations. Harvard Business School Press: Harvard.

- Price, V. (1992). Communication concepts 4: Public opinion (Kindle Edition). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- PRSA. Public relations defined. A modern definition for the new era of public relations http://prdefinition.prsa.org. 11 April 2012.

- Pye, W. L. (1965). Political culture and political development. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400875320-002

- Rawlins, B. (2008). Measuring the relationship between organizational transparency and trust. Public Relations Journal, 2(2), 425–439.

- Ruef, M., & Scott, W. R. (1998). A multidimensional model of organizational legitimacy: Hospital survival in changing institutional environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4), 877–904. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2393619

- Scott, W. R. (2003). Organizations, rational, natural, and open systems (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Selznick, P. (1949). TVA and the grass roots. A study in the sociology of formal organization. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Thompson, J. D. (1967). Organizations in Action. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Tyler, T. R., & Fagan, J. (2008). Legitimacy and cooperation: Why do people help the police fight crime in their communities. Journal of Criminal Law, 6(1), 231–275.

- Verba, S. (1965). Comparative political culture. In W. L. Pye & S. Verba (Eds.), Political culture and political development Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400875320-013

- Willmetts, S. (2019). The cultural turn in intelligence studies. Intelligence and National Security, 34(6), 800–817. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2019.1615711

- Woodward, J. (1958). Management and technology. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.