ABSTRACT

The recurrence of ever more destructive economic crises and patterns of pervasive indebtedness and inequality threaten the social fabric of our societies. Our main responses to these trends have been partial, focusing on symptoms rather than causes, often exacerbating rather than improving the underlying socio-economic dynamics. To reflect on these conditions and on ‘what needs to be done’ this article turns to a similar socio-economic malaise faced by the city-state of Athens in the 6th century BC. Most historical studies dealing with this crisis focus on the comprehensive debt relief policy (seisachteia) implemented by Solon. We argue that this debt relief, although necessary, was the least important of Solon’s reforms. Solon read the problem of debt as a problem of money so he went on to reform the monetary and exchange system. However, he did not think that these reforms alone could restore socioeconomic sustainability. For this, a redefinition of what was counted as valuable economic activity and as income had also to take place. Moreover, for all these to work, citizens had to be involved more in the commons. Far from only achieving socioeconomic sustainability, these reforms gave rise gradually to the demos that we meet in the golden age of Democracy. Such a broad historical horizon may help us grasp better the problems, stakes and challenges of our times.

Introduction

Income and wealth inequalities, alarming environmental degradation and seemingly uncontrollable debt dynamics put our global socioeconomic system under strain. The challenges ahead of us are not easy to exaggerate. Can our economies keep growing as they have done up to now? Is it possible to face destabilising socio-economic inequalities and achieve socioeconomic sustainability without growth? What do we ‘count’ as economic growth and income, and why? The answers to these questions are not predetermined. Different ways of thinking and different responses to these challenges will trigger different transformation dynamics and generate different outcomes. The greatest challenge of all then may be to decide where we want to go from here: what characteristics of our societies we want to maintain and what aspects we want to change.

A number of proposals on what needs to be done today have been put forward. For instance, a number of authors have suggested the need for direct debt write-offsFootnote1 and/or the use of ‘helicopter money’.Footnote2 Other ideas include the implementation of a universal basic income or universal job guarantee scheme, a redefinition of the policy of inflation targeting, or a change in the GDP/growth measurement in a way that better reflects social values and environmental impact. In the first part of this introduction, we offer a historical perspective on some of these proposals and, most importantly, on the way they relate to each other. To do this we go back in time to see how a different society, in a different epoch, which faced a similar socioeconomic malaise to ours, dealt with its predicament. This is not an exercise in drawing lessons from history but opening up the horizon of our current predicament might help us to understand where we stand today and how we can move forward.

The second part of the introduction discusses the contribution of the articles included in this collection. Here we focus on the new insights and findings generated by the collection and how these may help us to draw a more accurate map of the political economy of debt dynamics in the global economic system.

Economic crisis and the constitution of Athens

At the beginning of the 6th century BC, the city-state of (pre-democratic) Athens was undergoing a severe socio-economic and political crisis. In Parallel Lives,Footnote3 Plutarch stresses two things.Footnote4 First, there was an overly fragmented political scene with three main parties: one pro-democratic, one pro-oligarchic, and one which ‘favoured an intermediate, mixed kind of system’, and its presence made it difficult for either of the first two parties to gain power. The established political structure of interest representation was therefore at stalemate and seemed obsolete. Second, social inequalities were out of control and the cleavage between aristocratic landowners and poor farmers had reached explosive dimensions. The great majority of the population was in debt, and many lived ‘on the starvation line’.Footnote5 These developments were racking the social fabric and bred a violent social response. A long quotation from Plutarch is useful here:

[T]he disparity between rich and poor had…reached a peak. The city was in an extremely precarious state, and it looked as though the only way it could settle down and put an end to all the turmoil was by the establishment of a tyranny. All the common people were in debt to the wealthy members of society, because either they paid them a sixth of the produce they gained from working the land…or else they put up their own persons as collateral for their debts and were forfeit to their creditors, in which case they might become slaves right there in Attica or be sold into slavery abroad. The creditors were so ruthless that people were often forced to sell even their own children…or to go into exile.Footnote6

Aristotle paints a similar picture in the Constitution of AthensFootnote7:

[T]he upper classes and the people were divided by party-strife for a long period, for the form of government was in all respects oligarchical; indeed, the poor were in a state of bondage to the rich, both themselves, their wives, and their children… Now, the whole of the land was in the hands of a few, and if the cultivators did not pay their rents, they became subject to bondage, both they and their children, and were bound to their creditors on the security of their persons…

Some researchers speculate that the increase in debt and debt bondage in Athens was due to a fall in productivity (to put it in modern parlance). Unlike many Greek city-states, Athens had not had relieved pressure on local resources by sending part of its population to new colonies. The growing population in Athens led to a more intensive cultivation of land, diminishing the fertility of the soil. Peasants who might not produce enough for the year, would borrow money from landowners by pledging parts of next year’s harvest.Footnote8 Yet, with falling productivity/fertility each year, more and more farmers failed to meet their debt obligations, entering into debt bondage relations with their creditors.Footnote9

A further reason that has been advanced for Athens’ debt pathologies was a shift in ‘monetary regime’ (again in modern parlance), that is the ‘transition from natural economy to money economy based on a metal currency’.Footnote10 This exposed peasants to a different economic system, that followed different rules, was determined by different forces and generated different forms of fluctuation and speculation than those they, and earlier generations of peasants, were used to. It was not only a problem of comprehending and adjusting to a new monetary system. It was also, and perhaps most importantly, that in this new system power was moving away from peasants and their produce, towards money and finance. In the new money economy, peasants could not affect the conversion of farm produce to silver (needed to repay their debts), nor could they control the timing of debt repayment, that is the fact they had to sell their produce ‘just after harvest, when grain was plentiful and cheap’.Footnote11 In a rather exaggerated but suggestive statement, Milne notes: ‘if the financiers chose to manipulate the exchanges, it is most probable that they would have had the farmers at their mercy’.Footnote12 It can then be safely assumed that these changing rules of the game and shifting power relations had significantly contributed to the pattern of widespread indebtedness experienced in Athenian society.Footnote13

Another reason for Athens’ economic malaise relates to significant shifts in the characteristics of international production and distribution networks. During the late 8th and early 7th century BC the main maritime trade power in Greece was Aegina. Athens’ share in overseas trade was rather limited. Yet around this period a significant reorganisation of the Greek city-states’ established import/export patterns took place, through the emergence of a new international trade triangle among Greece, Ionia and Egypt. Traditionally, Aegina would import corn from Athens. Yet, Aeginetans had started to import cheaper corn from Egypt in return for their silver, which was valued much higher in Egypt than in Athens. Once Aegina covered its domestic needs in corn, it started to export corn to Athens at prices much lower than those requested for Athenian corn. In this context, Aeginetans would ‘bring over all the cargoes of corn that they could carry and flood the Greek markets with cheap corn’, thus delivering an additional hit to Athenian corn producers.Footnote14

To deal with the destructive pattern of widespread indebtedness and debt bondage, break the political stalemate and avoid an all-out social war, Athenians agreed to invite Solon and asked him to find a solution for Athens’ economic malaise. Solon was elected as Archon in Athens in 594 BC,Footnote15 in what must have been an unenviable position. The powers given to him were well short of those of a tyrant, and therefore the chances of successfully implementing any reforms were very thin, if any. Reinforcing the powers of the landowners would lead to social chaos. Going ahead with a radical redistribution of land would lead to war (and possibly to farmers’ massacre). No matter which course he would take, anger from those whose demands went unmet would be directed against him. Plutarch notes that even moderate Athenians thought it would be hard for Solon to deliver his reforms only through ‘reasoned argument and legal measures’, so they ‘did not dislike the idea of having a single person in charge’Footnote16 – put differently, of Solon imposing a tyranny.

Solon not only vehemently opposed retreating to tyranny as the only way forward,Footnote17 but also decided to follow a ‘middle way’ as a solution to Athens’ ills, a decision criticised by all main political parties. His reforms ‘annoyed the rich’, but also ‘the poor were even more aggrieved at his failure to redistribute land as they had expected, and because he had not completely removed the disparities and inequalities between men’s lives and incomes, as Lycurgus had done [in Sparta]’.Footnote18 Yet, Solon’s reforms seem to have been based on a comprehensive understanding of how to address the sources of debt dynamics without reverting to a social revolution (in the form of radical land redistribution). First, he directly liberated people and the land from debt and debt bondages. Second, based on a rethinking of basic Athenian assumptions of what money is, what it does in the economy, and what counts as income, he implemented reforms related to money and income. Third, he enhanced the role and participation of the lower classes in the commons by creating new rights and socio-political institutions.Footnote19 As Chambers puts it the ordering of Solon’s reforms and priorities was ‘cancellation of debts-metrological reforms-legislation’.Footnote20

Solon’s first act in office was the seisachtheia,Footnote21 which involved the cancellation of all debts, private and public, and the cancellation of all debt-related claims on land (mortgaged land).Footnote22 The act also forbade the enslavement of Athenian citizens for debt (debt bondage) and foresaw the liberation of Athenians who were enslaved. In this way Solon was creating a new sense of community based on a notion of citizenship that was defined against debt enslavement. Grote describes the act of seisachteia as followsFootnote23:

It cancelled at once all those contracts in which the debtor had borrowed on the security either of his person or of his land; it forbad all future loans or contracts in which the person of the debtor was pledged as security; it deprived the creditor in future of all power to imprison or enslave, or extort work from his debtor…It liberated and restored to their full rights all debtors actually in slavery under previous legal adjudication; and it even provided the means…of…bringing back to a renewed life of liberty in Attica, many insolvents who had been sold for exportation.

Yet, seisachtheia was only one pillar of Solon’s economic reforms. Solon understood that the debt malaise was an expression of a deeper structural problem. Cancelling the debt without dealing with the sources of the debt problem would just postpone the crisis. Solon not only had not outlawed debt, but deemed its existence, that is the capacity to borrow money, important for the economy and economic expansion (see the following text). To deal with the structural causes of indebtedness Solon’s next reform focused on the monetary system and related measurements.

Milne notes in this regardFootnote24:

But it would have been of little use to do…[the seisachtheia] unless he had at the same time provided some safeguard against the recurrence of the trouble: this [i.e. farmer’s insolvency] had been so widespread that it must have been due to some cause which operated throughout the industry, not to the shortcomings of individuals; and, as the step which Solon took was to reform the currency, it is clear that in his view it was the currency which had been at fault.

The key reference for this reform is found in Aristotle’s The Constitution of Athens, where it is noted that Solon ‘instituted the cancelling of debts, and afterwards the increase in measures and weights, as well as in the current coin’.Footnote25 A similar phrase is found also in Plutarch who notes that Solon’s seisachtheia ‘also covered the upward rescaling of the weights and measures and of the value of the currency’.Footnote26 There is no agreement amongst scholars what these reforms in measures, weights and the value of currency meant exactly in practice.Footnote27 The point is that Solon read the problem of debt as a problem of money, and the problem of money as both an economic and a political problem. His economic reforms in this context had a double purpose. In the short term, by reforming the weights and the value of the currency he aimed to support indebted citizens, which ‘benefited the debtors a great deal’.Footnote28

But most importantly Solon must have thought that a solution to the Athenian debt malaise was not possible without a reshaping of the dominant monetary system of his time. For most of the 7th century BC the main ‘international currency’ in Greece, that is the currency that was used in the settlement of weights, measures and trade between Greek city-states, was issued in Aegina (based on a standardisation of weights and measures achieved around 670 BC by Pheidon the ruler of Argos), and its value was determined by the price of silver bullion in Aegina’s metal market. Aegina controlled also the then main silver-mines in Greece, e.g. in Siphnos.Footnote29 The fact that Athens did not have much control over weights, measures and currency valuations was one further factor negatively affecting the transition from a ‘natural’ to a money economy in Athens. Solon’s reforms gave rise to a new coinage that managed to replace the dominance of the Aeginetan coins, first in Attica, then in the trade among Greek city-states, and finally in Greek trade overseas. The final solution to the problem of access to silver, on which Solon’s monetary reform was based, was given with the discovery of silver-mines in Laurium,Footnote30 that served Athens for most of its ancient and classical history (and beyond).Footnote31

Along with seisachtheia and the reform of the money system, the third pillar of Solon’s reform was a reform of ‘what counts as income’. Solon instituted a new division of Athenian citizens into classes. In the new system, citizens no longer inherited their class membership, but the latter was determined by their wealth. Although this reform did not satisfy the poorer classes that demanded full political representation and the right to be elected, the implications of this reform were far-reaching. Till that point only the members of a hereditary aristocracy, i.e. the members of the highest class of ‘eupatridai’, could be elected in significant political positions. Solon’s reform replaced ‘birth with wealth’Footnote32 as the qualification for social class and political office, thus making social mobility between classes possible.Footnote33 For the purposes of this article, another aspect of this reform is equally interesting. Traditionally, wealth that ‘counted’ for the purposes of social class classification, came only from produce from land, an exclusive privilege of land-owners. Respectively all weights and measures were set in terms of measuring dry and wet goods.Footnote34 This system excluded all other classes, such as merchants, which generated wealth but in the form of money-income rather than land produce. Solon changed this by redefining what was to be counted as wealth. As Freeman notes,Footnote35 researchers have argued that:

the use of annual produce from land as a medium of assessment in all four classes – was pre-Solonian, and that Solon’s work consisted in admitting as well a money-income of the same value, thus depriving landed property of its privilege, and opening the way to office for the merchant class.

Solon understood that reforming debt and money alone might not cure Athens’ pathologies. This required a rethinking and redefinition of wealth and income. New social values and practices had to be accompanied by new social valorisations that reflected and validated these new practices and social dynamics, if the social system was to be stabilised, and Solon implemented this.Footnote36

History proved Solon’s comprehensive response to Athens’ debt malaise right. Solon did not only treat the symptoms of Athenian malaise (excessive and wide spread indebtedness) but managed to locate and deal with its causes too. Seen through a contemporary lens, Solon dealt with the problem of social destructive indebtedness as simultaneously a problem of debt overhang, citizenship, money, and income. Yet, from today’s perspective, the restoration of socio-economic sustainability in Athens seems to have been the least of what Solon achieved. Solon’s reforms not only arrested the dissolution of Athenian society but also forged a new sense of citizenship and community. These reforms gave the flesh and bones to the demos rising in Athens’ golden age of democracy in the 5th century BC. The idea and practice of Democracy, therefore, finds its origin in a society’s response to a major social crisis, defined by destabilising inequalities, pervasive poverty and indebtedness, and calls for the replacement of a discredited political establishment.

Parallel lives of debt pathologies?

History does not hold the answer to our present problems but the similarities between the socioeconomic crisis described above and the one we are in today are intriguing. So to is the idea that a response to our socioeconomic crisis may, in time, not only solve the current crisis but forge new social and political subjectivities that will breathe new life and meaning in modern democratic theory and practice. This section offers a brief examination of some similarities between the Athenian debt malaise and today’s juncture, and discusses what we can learn from Solon’s response to the Athenian crisis.

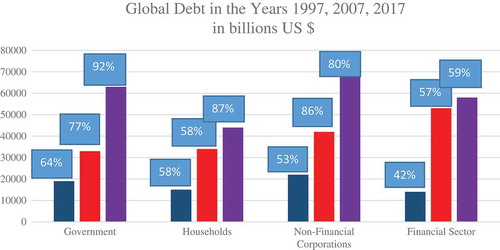

All international organisations monitoring global debt today agree that it has reached historically unprecedented levels.Footnote37 According to the Institute of International Finance (IIF) global debt increased from $73.6 trillion in 1997 to $166 trillion in 2007, and reached $237 trillion in 2017.Footnote38 Equally worrying is the fact that these debt dynamics are not driven by any single type of debt, or any single region. As evident in all types of debt, i.e. government, household, non-financial corporations (NFC), financial sector, have been significantly increasing over the last 20 years, especially so after the global economic crisis.

Figure 1. A city in an extremely precarious state: debt, inequality, money colour.

Note: Boxes indicate per cent of global GDP per annum.Source: Authors based on data from IIF, 2018.Footnote39

This rapid growth of global debt has been accompanied by a rapid growth in economic inequalities. The latter has been driven by a significant change in income distribution in favour of capital income and against labour income after the 1980s.Footnote40 This change in income distribution was translated into rising household indebtedness. For instance in 2016, the level of household debt as a percentage of disposable income was 111% in the United States, 153% in the United Kingdom, 178% in Canada, 179% in South Korea and 221% in Australia. Even in societies with lower levels of private indebtedness such as Italy and France, the household-debt-to-income ratio has increased from 38.5% and 66.4% respectively in 1995, to 88% and 109% in 2016.Footnote41 The corresponding wealth inequalities are even more staggering. At a global level ‘[t]he bottom 50 percent of the global population has near-zero wealth and almost half of global wealth is held by the top 1 percent’.Footnote42 The implications of these trends are pervasive and of course ‘precariousness’ is unequally distributed both across and within countries. It is indicative that in the UK, one of the ‘richest countries’, only 2% of households have deposit holdings in excess of £5000.Footnote43 Furthermore, individuals with debt aged 16–24 have the highest level of debt compared with their income, while half of adults in debt in the lowest net income quintile report debts of 83% or more of their annual income (Office for National Statistics, 2016). The ways in which these debt dynamics crash everyday livelihoods and monetise, their future is hard to exaggerate.

The debt conundrum of our times is now widely recognised. The former governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, argues that: ‘[d]ebt has now reached a level where it is…likely to be the trigger for a future crisis’.Footnote44 The former governor of the Reserve Bank of India and vice-chairman of the Bank for International Settlements, Raghuram Rajan, has referred to the long-term build-up of destabilising inequalities as a period in which the main mantra of the political establishment was ‘let them eat credit’.Footnote45 The former chairman of Britain’s Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner, entitled his book Between Debt and the Devil (2016). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has pointed to the negative impact of excessive inequalities on growth.Footnote46

Social theory has tried to capture and conceptualise these processes in different ways. For instance, as a new market civilisation,Footnote47 a new social technology of governance and control,Footnote48 or the new ordering divide of capitalism, which replaces the traditional capital-labour relationship.Footnote49 Other researchers have referred to a new political economy of debt, a debt-based economy, a credit-driven or credit-intensive economy,Footnote50 privatised Keynesianism,Footnote51 or the house of debt.Footnote52 Regardless of the differences between these authors, they all agree that the current debt and inequality trends are unsustainable. Rising indebtedness, and income and wealth inequalities, rip the social fabric of our societies and the global economy in ways similar to that described by Aristotle and Plutarch in the preceding text.

There is also some overlap on the discourses about the causes of the debt crises in ancient Athens and the current juncture. The fall in productivity in Athens concurs with current discussions on secular stagnation. The emergence of a new financial system, in which power is moving away from producers and their produce towards money and financiers, concurs with contemporary discussions on financialisation. Changes in Athens’ production and distribution networks correspond to current trends of globalisation of production and global value chains. The contemporary value of ancient Athens’ debt malaise, however, is to be found in the way in which Solon construed the crisis, as well as to the broader political implications of his response.

Solon did not think that the problem was with debt itself, that is that debt is harmful in economic life. On the contrary, according to some scholars, he thought that the existence of a money market and the capacity to raise capital for productive activities were necessary and useful aspects of an economic system. This was evident in the case of Athens, which encouraged the production of olive oil. The growth of olive trees to productive capacity takes time, so access to borrowing and capital was a key aspect of the Athenian economic system.Footnote53 Neither apparently, Solon thought that the problem was the profligacy by some or a period of excess by many that could be solved through increasing taxes and imposing austerity. Solon construed the debt malaise as a multilevel problem with different aspects and sources feeding each other. He understood that dealing with any single of these aspects without addressing the others would postpone but not solve the problem.

Thus, to avoid a social collapse and/or outright revolt, Solon first took measures to relieve citizens from the burden of indebtedness. Then he moved on to tackle the structural sources of the problem of indebtedness by reforming the monetary and exchange system. However, he did not stop there, possibly because he thought that without allowing for a better and fairer balancing of the economic system with the (changing) social values and activities, the return of social unrest, debt malaise or both could not be averted. Thus, he went ahead allowing the redefinition of what was counted as income, that is, what forms of social and economic activities were valuable and contributed to the collective welfare, but due to privilege, tradition or both were not counted as income. However, Solon did not stop at the definition of income either.

As mentioned above his reforms ‘did not meet the approval of either party’.Footnote54 Initially both the ‘the rich’ and ‘the poor’ were dissatisfied with his reforms because their demands had not been met. Furthermore, the general consensus in Athens at the time was that Solon’s reforms would fail if he did not adopt a more autocratic style of governing. Against all advice and odds, Solon did the opposite. He gave more voice to the people and increased their role in the commons.Footnote55 He must have believed that this was the only way for his reforms to survive and succeed – people had to become part of the political structure on which his reforms were based.Footnote56 Thus his ‘economic reforms’ were invested and supported by ‘innovations’ in the city’s political structure and mode of organisation, as the ultimate and maybe the most critical step for securing his reforms. All together, Solon’s reforms had a completely unforeseeable outcome with far reaching implications for human civilisation, to put it in grandiose terms. They redefined and gave rise to a new political subject, the demos, a new political space, the commons, and most importantly a unique mode of symbiosis between these two that gave rise to Democracy, the ideal and the praxis that inspired and determined human history thereafter.

The window for rethinking our socio-economic system and the ways we study it, opened by the global economic crisis, should be kept open. In this regard, the debt crisis in 6th century BC Athens conveys three relevant messages. First, attempting to deal with different symptoms of economic malaise without addressing its causes may postpone but cannot avert a systemic crisis. For instance, less than 15 years after the debt relief given to heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC), the problem of their debt sustainability is back. Actuarial studies have pointed to the unsustainability of many pension schemes around the world for more than 20 years. Year after year there are adjustments in benefits and pension cuts aimed at improving the sustainability of these schemes only to be proven too little (sometimes too late) some years later. Similarly, no matter what austerity measures are imposed or how many public assets are sold, the sustainability of free public services, such as health, seems like a promethean task. These examples illustrate that the sustainability of our socio-economic system cannot be restored by dealing with symptoms rather than causes, and without addressing the question of where we want to go from here.

Second, although the different causes of our economic crisis may be analytically distinct, in practice they are interrelated and feed each other. For instance, dealing with the supply-side of debt (e.g. banks and credit allocation) without addressing the demand side (e.g. economic inequalities, poverty, precarious employment) will not solve the problem. Similarly, offering debt alleviation or welfare support without reducing the dependency of our monetary system on interest-bearing money and redefining what we count as economic activity will fail to set our socioeconomic (and environmental) system on sustainable tracks. Thus, the emphasis should be on connecting the dots between the causes of economic malaise (from credit allocation, to inequality, to money creation, to what we count as GDP). None of Solon’s measures was ‘revolutionary’ or ‘radical’ in its context (for which he was criticised), but the comprehensiveness of his reform package achieved more than most revolutions in recent history.

Third, significant socio-economic reforms cannot succeed without the participation of people affected by them. Renewing and enhancing citizen engagement with the commons may give rise to a new ‘political contract’ and lead to a democratic renewal of our societas economicus. This might be deemed wishful thinking if history did not teach us otherwise.

The contribution of this volume

This volume aims to advance debt studies by bringing together a number of recent, less explored debt crises from different regional and socioeconomic contexts. Dushni Weerakoon offers a fascinating analysis of Sri Lanka’s debt troubles in the new development finance landscape. She demonstrates how the country’s graduation to a low middle-income country in 2010, the rise of new lenders (especially China), and the search for yields in international markets created a range of new opportunities and challenges for Sri Lanka. Access to international financial markets and development finance by new lenders gave a much-needed boost to Sri Lanka’s public investment programme, and created new possibilities for state-owned enterprises and local corporations. Yet, at the same time, there has been a significant change in the country’s external debt profile, with non-concessional foreign debt rising from 7 per cent in 2006 to approximately 55 per cent in 2016. Furthermore, the rise in debt-generating external financing has not been accompanied by sustained export earnings growth or non-debt generating capital inflows that would allow the country to service its external debt. The broader geo-economic picture and strategies of regional powers complicate further local debt dynamics and debt management. As a result of these trends, Sri Lanka entered a three-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) IMF programme in June 2016, and now ‘finds itself in a vicious cycle of further foreign debt intake to build up reserves as a condition of its EFF programme in an environment of fiscal austerity that dampens growth’.Footnote57 Weerakoon’s analysis generates evidence and insights on new ‘debt traps’ generated in the current development finance environment and how developing countries can avoid them.

Kristina Hinds and Jeremy Stephen shift our focus from South Asia to the Caribbean. They analyse the current debt crisis in Barbados in comparative perspective with the island’s 1991–1993 crisis, which led to an IMF support programme. The authors analyse the external and domestic sources of the crisis, adding new insights on the challenges and dilemmas that (small) countries face in achieving socially inclusive, sustainable development. Barbados went through a long period of high growth rates (1994–2008) but the global financial crisis hit hard the island’s tourist economy and trade partners at a moment when its fiscal position was rather exposed (also due to preparations for the Cricket World Cup in 2007). The prolonged recession that followed forced Barbados to spend 63 per cent of its revenues on servicing its public debt in 2010, and this number remained above 50% in 2013 and 2014. Similarly, after 2010 interest payments on public debt remained above 20 per cent of government revenues. The government attempted to face the adverse debt dynamics through domestic borrowing from the National Insurance Scheme (NIS), but the risks to NIS’ portfolio and credit rating forced the government to change strategy. It thus turned to the Central Bank of Barbados and money printing. Considering the pegged exchange rate regime of Barbados, this had a negative knock on effect on the Central Bank’s foreign reserves and therefore its capacity to defend its pegged rate. After moving away from the debt trap of the early 1990s, Barbados seems to have been led to another debt trap that once more puts the future of the ‘Barbados model’ and ‘success story’ of the Caribbean in question. The experience of the 1990s crisis has been formative in this context. As the authors note ‘some of the policies pursued in Barbados to respond to the post-2008 crisis reflect the success of IMF influence in affecting a paradigm shift that has shaped policy-makers’ views of the options available’.Footnote58

The next three articles focus on different ‘peripheries’ of Europe. Neil Dooley focuses on the Eurozone and the case of Portugal. Bringing together insights from the comparative political economy and Europeanisation literatures, he develops a fascinating and novel account of the origins of the debt crisis in Portugal. To understand the origins of this crisis, Dooley invites us to go beyond arguments about ‘institutional stickiness’ and the periphery’s failure to modernise after joining the euro. The origins of the Portuguese crisis are (at least equally) to be found in the implementation by Portugal of EU harmonisation policies aiming at the deregulation of the financial sector and credit provision. The latter policies led to a credit-fuelled boom in the 1990s, and, as a result, increased leverage and indebtedness in the private sector, and led to an expansion of the non-tradable sector. This new debt-based growth model became a drag for economic growth. As Dooley says, ‘the limits of this new model became evident in the early 2000s when declining export competitiveness was not counterbalanced by domestic demand led growth – because of over-indebtedness’.Footnote59 Dooley’s analysis adds new insights on the potential pervasive and destructive impact of financialisation in advanced economies. Yet his conclusion is not that European economic and monetary integration was a bad idea. Rather Dooley concludes that ‘[t]he challenge is not to heedlessly push for future convergence, but to envision ways in which virtuous patterns of divergence can be cultivated within a project of integration’.Footnote60

Dora Piroska moves the analysis outside the Eurozone by focusing on the case of Hungary. Her analysis generates new evidence and insights on the competing readings of Hungary’s financial crisis by the troika institutions (i.e. IMF, European Commission, ECB) as well as the implications of these competing readings in terms of the management of the Hungarian economic crisis. Her analysis focuses on a critical aspect in the study of debt crises: the way in which a debt crisis is construed and framed is not an ‘objective’ exercise but determined by the underlying power relations (ideational and material). It is these power relations that determine the response to each crisis. Piroska illustrates that the reading of the Hungarian crisis by the three involved institutions was not determined only by the mandate of these institutions, but by the nature of their expertise, their prior interaction with, and knowledge of, Hungary and its economy, as well as the way in which these institutions read their interests and formed their priorities. Thus, on the one hand the IMF stressed the international dimension of the crisis – the sudden drying up of liquidity in the international financial markets and the implications that this had in a country of which the banking sector was dominated by foreign, Western European parent banks. Consequently, IMF’s priority was to secure the stability of the banking sector. On the other hand, the European Commission and the ECB saw the crisis primarily as a ‘Hungarian crisis’ resulting from fiscal expansion and an unbalanced budget. Thus, they recommended austerity and a balanced budget as a solution. The ECB’s priority was to protect the Eurozone’s banking sector and to reduce the Eurozone’s exposure to the Hungarian Crisis, disregarding the implications of this policy for the Hungarian economy. The outcome of these competing readings was not a clear compromise between the involved institutions, but rather a longer list of conditionalities and on-going frictions. As Piroska notes, ‘overcoming the contrasting crisis management priorities…proved to be the greatest challenge for national policy makers’.Footnote61

Will Bartlett and Ivana Prica analyse debt dynamics in Europe’s ‘super-periphery’, the Western Balkans – a region outside both the Eurozone and the EU, but economically tied to the EU. They demonstrate how the collapse of credit, FDI and remittances triggered by the global and European economic crises bankrupted large segments of the six Western Balkan economies. This resulted in a rapid increase in public borrowing aiming to avert social collapse and preserve social peace. In the most extreme case, Serbia, public debt increased from €8.9 billion in 2007 to €25.2 billion in 2015. These adverse debt dynamics forced the Western Balkan countries to seek support from the IMF, with all the respective programmes aiming to achieve fiscal consolidation through austerity. Bartlett and Prica argue that this austerity context entrenched the traditional pathologies of the local political systems that in most cases are based on patronage relationships and clientelistic practices. As a result public and external debt dynamics and prospects for economic recovery deteriorated. However, this is not a crisis confined only in the economic realm. Worsening socioeconomic conditions and austerity policies seem to generate a broader socio-political crisis that affect the function of democracy. The local ruling parties reacted to the loss of popular support due to the imposition of austerity measures, ‘by a reversion to authoritarian and illiberal modes of political culture’.Footnote62 Bartlett and Prica contribute to the current literature on debt dynamics by throwing the spotlight on the challenges faced in the socioeconomic space of Europe’s super-periphery.

Shakira Mustapha and Annalisa Prizzon expand the scope of our investigation by reviewing existing evidence on the impact of recent, international debt relief initiatives, and examining the new challenges, opportunities and threats generated for low income countries (LIC) by the fast changing development finance landscape.Footnote63 The great majority of the countries that benefited from the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative are facing again heightened risks in their debt sustainability. To understand the drivers behind these debt dynamics, as well as the challenges ahead, Mustapha and Prizzon examine four significant changes in the development finance environment: (a) the fact that some countries may no longer be eligible for IDA-World Bank concessional loans, (b) the fact that many countries have been borrowing from international capital markets at low interest rates (in the current global accommodating environment) and in foreign currencies, mostly US dollars, (c) the increase in the use of public-private partnership arrangements in the context of development finance, and (d) the significant increase in lending from ‘emerging donors’. According to Mustapha and Prizzon none of these developments is purely negative but equally none is without significant associated risks (the case of Sri Lanka mentioned above is indicative). The authors suggest that beyond the new structure of development finance, equally significant is the agency on the ground by the involved actors. That is, the strategies and policies developed by countries and international organisations to increase their resilience and debt management capacity, as well as the capacity of the international system to deal with debt crises in an orderly way.

Kathrin Berensmann concludes the problematique of this volume by offering a comprehensive analysis of the current Global Debt Governance System (GDGS).Footnote64 The GDGS fails both to prevent and to effectively resolve debt crises and Berensmann analyses why this is so and what needs to be done. First, the author offers a concise mapping of the main aspects of the existing global debt governance mechanisms. She distinguishes between ‘crisis prevention’ and ‘crisis resolution’ instruments. Crisis prevention includes instruments such as existing debt monitoring mechanisms by international organisations, codes of conducts, as well as a range of economic policies, such as the development of local currency bond markets. Crisis resolution includes instruments such as debt relief initiatives by international organisations, debt-restructuring mechanisms such as the Paris and London Club, collective action and pari passu clauses, codes of conduct, and debt swaps. The author analyses the main problems in the existing GDGS and assesses the strengths and weaknesses of each of the aforementioned instruments. On the basis of this analysis, Berensmann advocates the need for reforms at three levels: the instruments within each of these two sets of tools (i.e. ‘crisis prevention’ and ‘crisis resolution’) need to be better aligned and integrated; better coordination and more integration between the two different sets of tools; and the creation of new instruments, especially the long-discussed insolvency procedure for states. Berensmann explicates what these reforms mean in practice and how they can be implemented.

The debt dynamics that emerge from the above analyses are not new but this does not make them less worrisome. There is a clear pattern of continuous debt build-up and of recurrence of debt crises. Furthermore, each new debt crisis seems to have ever more pervasive social and political implications in comparison to its predecessors. More social provisions are eradicated, larger parts of the middle classes seem to collapse, more poverty and inequality is generated, democratic rules and institutions and democracy itself come under increasing strain. These trends are complicated further by a new ‘rise of geopolitics’. To arrest and reverse these destabilising dynamics demands change to the dominant parameters that define current thinking and policy-making with regard to debt. As this introduction argues, going back to basics and asking what kind of problem debt is, and where it comes from, is a key step in this process.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants in the inaugural workshop of the Global Debt Dynamics Initiative that took place in Brighton on 26 May 2016, Louiza Odysseos, the anonymous reviewers of the articles of this volume, and the Editors of the Third World Thematics, and especially Madeleine Hatfield, for all their cooperation, feedback and support. Andreas Antoniades would like to acknowledge funding from the Research Opportunities Fund of the University of Sussex.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andreas Antoniades

Andreas Antoniades is Senior Lecturer in Global Political Economy at the University of Sussex. He has previously taught at the universities of Essex, Panteion and the London School of Economics, from where he has received a Teaching Prize in International Relations. He is the convenor of the Global Debt Dynamics Initiative (https://globaldebtdynamics.net), and has been the director of the Sussex Centre for Global Political Economy, and the Athens Centre for International Political Economy. He is the Principal Investigator in the SSRP project ‘Debt and Environmental Sustainability’. He has served as a vice-chair in the ECOSOC panel of the MSCA-ITN programme of the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, European Commission. His work has appeared in several journals including The World Economy, Review of International Political Economy, Global Policy, Third World Quarterly, and British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

Ugo Panizza

Ugo Panizza is Professor of Economics and Pictet Chair at the Graduate Institute, Geneva. He is also the Director of the Institute’s Centre on Finance and Development, and a CEPR Research Fellow. Prior to joining the Institute, Ugo was the Chief of the Debt and Finance Analysis Unit at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). He also worked at the Inter-American Development Bank and the World Bank and was an assistant professor of economics at the American University of Beirut and the University of Turin. His research interests include international finance, sovereign debt, banking and political economy. He is a former member of the executive committee of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association (LACEA) and an editor of the Association’s journal Economia. He is also a member of the editorial board of The World Bank Economic Review, the Review of Development Finance, the Journal of Economic Systems, and the Review of Economics and Institutions. He holds a PhD in Economics from The Johns Hopkins University and a Laurea from the University of Turin.

Notes

1. For instance, Mian and Sufi, House of Debt; King, The End of Alchemy; Turner, Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit, and Fixing Global Finance; Keen, Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis?

2. For instance, Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks; Turner, Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit, and Fixing Global Finance; King, The End of Alchemy; Bernanke, ‘What Tools Does the Fed Have Left?’; Buiter, ‘The Simple Analytics of Helicopter Money: Why It Works – Always’; Keen, Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis?

3. For the purposes of this volume we use the following shorter edition in English that includes Solon’s biography: Plutarch. Greek Lives.

4. Plutarch, Greek Lives, 56.

5. See also Woodhouse, Solon the Liberator, 119.

6. Plutarch, Greek Lives, 56. For a discussion on the primitive law of debt and debt bondage in Athens see Woodhouse, Solon the Liberator, 67–73.

7. Aristotle, Constitution of Athens, 1.

8. As Woodhouse (ibid. 119) notes ‘up to about Solon’s time, or a little before, we are dealing with institutions and usages arising out of a system of natural economy, under which a loan, and interest upon it, took the form of a certain quantity of some raw product’.

9. See the discussion in Sealey, A History of the Greek City States, 109; Woodhouse, Solon the Liberator, 132–35; Milne, “The Economic Policy of Solon”, 233.

10. Woodhouse, Solon the Liberator, 136.

11. Woodhouse, 120.

12. Milne, “The Monetary Reform of Solon”, 180.

13. See Woodhouse, Solon the Liberator, 136–39; Milne, “The Monetary Reform of Solon”; Milne, “The Economic Policy of Solon”.

14. Milne, “The Economic Policy of Solon”, 233.

15. Aristotle, Constitution of Athens, 10; Plutarch, Greek Lives, 57.

16. Plutarch, Greek Lives, 57.

17. A decision that according to Plutarch (ibid. 58) ‘earned him a great deal of scorn’ by his fellow citizens.

18. Plutarch, Greek Lives, 60.

19. Solon’s reforms touched upon every aspect of political and social life. Our aim here is not to cover all his reforms but to focus mainly on those related to the economy and are relevant to the theme of our volume.

20. Chambers, “Aristotle on Solon’s Reform of Coinage and Weights”, 2.

21. Seisachtheia (σεισάχθεια) is a composite word in Greek. It comes from the word ‘σείω’ (shake) and ‘ἄχθος’ (burden), so it means relief/alleviation of burdens. That’s why many authors have translated the term as ‘alleviation’.

22. In this sense, it can be argued that Solon’s reform did include a form of land redistribution for long as it returned land to peasants free of mortgage and debt claims. See Woodhouse, Solon the Liberator, 135–36.

23. Grote, A History of Greece, 21.

24. Milne, “The Monetary Reform of Solon”, 179.

25. Aristotle, Constitution of Athens, 22.

26. Plutarch, Greek Lives, 59.

27. For a discussion and relevant sources see Chambers, “Aristotle on Solon’s Reform of Coinage and Weights”. For a contrasting view see Milne, “The Monetary Reform of Solon”, 45.

28. See note 26 above.

29. Milne, “The Economic Policy of Solon”, 235. See also Freeman, The Work and Life of Solon, 90–111.

30. Laurium is a located in the southeast of Attica, approximately 60 km from Athens.

31. Milne, “The Economic Policy of Solon”, 241.

32. Sealey, A History of the Greek City States, 116.

33. Freeman, The Work and Life of Solon, 58. Solon made also a number of other reforms that increased the voice and power of lower classes in the Athenian commons; see ibid.

34. See Aristotle, Constitution of Athens, 14; Plutarch, Greek Lives, 61.

35. Freeman, The Work and Life of Solon, 58.

36. Not all researchers agree on whether this reform was implemented in Solon’s year. For a discussion see Freeman, 58–60.

37. For a recent review see Antoniades and Griffith-Jones, ‘Global Debt Dynamics: The Elephant in the Room’.

38. Institute of International Finance, “Global Debt Monitor”.

39. Indicatively see IMF, “Fostering Inclusive Growth”; Stockhammer, “Rising Inequality as a Cause of the Present Crisis”; ILO, “World of Work Report”; Jacobson and Occhino, “Labor’s Declining Share of Income and Rising Inequality”.

40. See OECD, “Household Debt”. For a recent overview of trends see World Inequality Lab, “World Inequality Report”.

41. IMF, “Fostering Inclusive Growth”, 6.

42. Carney, “The Spectre of Monetarism”.

43. King, The End of Alchemy, 337.

44. Rajan, Fault Lines.

45. See for instance Ostry, Berg, and Tsangarides, “Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth”.

46. Gill, “Globalisation, Market Civilisation, and Disciplinary Neoliberalism”.

47. Lazzarato, Governing by Debt; Soederberg, Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry; Robbins and Muzio, Debt as Power.

48. Lazzarato, Governing by Debt.

49. Turner, Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit, and Fixing Global Finance.

50. Crouch, “Privatised Keynesianism”.

51. Mian and Sufi, House of Debt.

52. Milne, “The Economic Policy of Solon”, 237.

53. Plutarch, Greek Lives, 60.

54. For instance, with Solon’s reforms all citizens could act as jurors and had the right of appeal to the court of justice. For the critical impact of these seemingly unimportant reforms on Athenian democracy and accountability see Aristotle, Constitution of Athens, 18–19; Plutarch, Greek Lives, 62. Furthermore, Solon created a new political body, the Second Council, which included representatives from all social classes, in contrast to the other political bodies that were open only to the higher social classes; see Plutarch, 62–63; Freeman, The Work and Life of Solon.

55. With regard to the nineteenth century democratisation reforms in the West, see Acemoglu and Robinson, “Why Did the West Extend the Franchise?”.

56. Weerakoon, “Sri Lanka’s debt troubles”, 15.

57. Hinds and Stephen, “Fiscal crises in Barbados”, 17.

58. Dooley, “Divergence via Europeanisation”, 14.

59. Ibid., 16.

60. Piroska, “Funding Hungary”, 2.

61. Bartlett and Prica, “Debt in the super-peripher”, 2.

62. Institute of International Finance.

63. Mustapha and Prizzon, “Debt relief initiatives 20 years”

64. Berensmann, “The global debt governance system”

Bibliography

- Acemoglu, D., and J. A. Robinson. “Why Did the West Extend the Franchise? Democracy, Inequality, and Growth in Historical Perspective.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115, no. 4 November 1 (2000): 1167–1199. doi:10.1162/003355300555042.

- Antoniades, A., and S. Griffith-Jones. “Global Debt Dynamics: The Elephant in the Room.” The World Economy (forthcoming). doi:10.1111/twec.12623.

- Aristotle. Constitution of Athens. Translated by Thomas J. Dymes. Online Library of Liberty, 1891. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/aristotle-constitution-of-athens.

- Bartlett, W., and I. Prica. “Debt in the Super-Periphery: The Case of the Western Balkans.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal (2018). doi:10.1080/23802014.2017.1438850.

- Berensmann, K. “The global Debt Governance System for Developing Countries: Deficiencies and Reform Proposals.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal (2018). doi:10.1080/23802014.2017.1433963.

- Bernanke, B. S. ‘What Tools Does the Fed Have Left? Part 3: Helicopter Money’. Brookings (blog), 11 April 2016. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2016/04/11/what-tools-does-the-fed-have-left-part-3-helicopter-money/.

- Buiter, W. “The Simple Analytics of Helicopter Money: Why It Works – Always.” Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal 8 (2014): 1–45.

- Carney, M. “The Spectre of Monetarism.” In Speech Given at Liverpool John Moores University. December, 2015. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2016/the-spectre-of-monetarism

- Chambers, M. “Aristotle on Solon’s Reform of Coinage and Weights.” California Studies in Classical Antiquity 6 (1973): 1–16. doi:10.2307/25010645.

- Crouch, C. “Privatised Keynesianism: An Unacknowledged Policy Regime.” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 11, no. 3 August 1 (2009): 382–399. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2009.00377.x.

- Dooley, N. “Divergence via Europeanisation: Rethinking the Origins of the Portuguese Debt Crisis.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal (2017). doi:10.1080/23802014.2017.1381571.

- Freeman, K. The Work and Life of Solon. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1926.

- Gill, S. “Globalisation, Market Civilisation, and Disciplinary Neoliberalism.” Millennium 24, no. 3 December 1 (1995): 399–423. doi:10.1177/03058298950240030801.

- Grote, G. “New Introduction by Paul Cartledge.” In A History of Greece: From the Time of Solon to 403 BC, edited by J. M. Mitchell and M. O. B. CAspari. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Hinds, K., and J. Stephen. “Fiscal Crises in Barbados: Comparing the Early 1990s and the Post-2008 Crises.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal (2017). doi:10.1080/23802014.2017.1408425.

- ILO. ‘World of Work Report’. Geneva: ILO, 2011 2008. http://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/world-of-work/lang–en/index.htm.

- IMF. ‘Fostering Inclusive Growth’. Washington DC: IMF, 2017.

- Institute of International Finance. ‘Global Debt Monitor’. Washington, DC: Institute of International Finance, April 2018. https://www.iif.com/publication/global-debt-monitor/global-debt-monitor-april-2018.

- Jacobson, M., and F. Occhino. ‘Labor’s Declining Share of Income and Rising Inequality’. Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, no. Number 2012–13 (September 2012).

- Keen, S. Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis? Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2017.

- King, M. The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking, and the Future of the Global Economy. New York; London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

- Lazzarato, M. Governing by Debt. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotexte, 2015.

- Mian, A., and A. Sufi. House of Debt: How They (And You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again. First Edition ed. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Milne, J. G. “The Monetary Reform of Solon.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 50 (1930): 179–185. doi:10.2307/626809.

- Milne, J. G. “The Economic Policy of Solon.” Hesperia: the Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 14, no. 3 (1945): 230–245. doi:10.2307/146709.

- Mustapha, S., and A. Prizzon. “Debt Relief Initiatives 20 years on and Implications of the New Development Finance Landscape.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal (2018). doi:10.1080/23802014.2018.1473047.

- OECD. ‘Household Debt’. Paris: OECD, 2018. doi: 10.1787/f03b6469-en.

- Ostry, J. D., A. Berg, and C. G. Tsangarides. ‘Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth’. Staff Discussion Notes No. 14/02. Washington DC: IMF, 2014. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2016/12/31/Redistribution-Inequality-and-Growth-41291. doi:10.5089/9781484352076.006

- Piroska, D. “Funding Hungary: Competing Crisis Management Priorities of Troika Institutions.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal (2018). doi:10.1080/23802014.2017.1435303.

- Plutarch. “Introduction and Notes by Philip A. Stadter.” In Greek Lives, edited by R. Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Rajan, R. G. Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy. Reprint ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Robbins, R. H., and T. D. Muzio. Debt as Power. Reprint ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

- Sealey, R. A History of the Greek City States, Ca.700-338 B.C. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

- Soederberg, S. Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry: Money, Discipline and the Surplus Population. 1 ed. London; New York, NY: Routledge, 2014.

- Stockhammer, E. “Rising Inequality as a Cause of the Present Crisis.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 39, no. 3 May 1 (2015): 935–958. doi:10.1093/cje/bet052.

- Turner, A. Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit, and Fixing Global Finance. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016. http://press.princeton.edu/titles/10546.html.

- Weerakoon, D. “Sri Lanka’s Debt Troubles in the New Development Finance Landscape.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal (2017). doi:10.1080/23802014.2017.1395711.

- Wolf, M. The Shifts and the Shocks: What We’ve Learned – And Have Still to Learn – From the Financial Crisis. London: Penguin, 2015.

- Woodhouse, W. J. Solon the Liberator: A Study of the Agrarian Problem in Attika in the Seventh Century. London: Oxford University Press, 1938.

- World Inequality Lab. ‘World Inequality Report’, 2018. http://wir2018.wid.world/.