ABSTRACT

While previous research has focused on the conflicts and division in Mitrovica, Kosovo, the present article explores how peace and conflict are intertwined in the post-war city by focusing on sites where communities live side by side in an otherwise segregated city. A key finding is that the most conflictual residential areas in northern Mitrovica also are places where what we call peace acts, peace issues and peace perceptions are found. Our research suggests that even in spaces in the city where a history of violence is entrenched, the situation can seldom be reduced to be seen only as purely conflictual; rather, these ‘hotspots’ often prove to be spaces where reproduction of peace – however quotidian – also occurs at the same time. This points us to the complexity of the realities of peace, where remnants of war and potential for a co-existing peace often overlap and are sometimes intrinsically intertwined.

Introduction

In February 2008, KosovoFootnote1 unilaterally declared independence from Serbia. Despite years of EU-facilitated talks between elites in Belgrade, Serbia and Pristina, Kosovo, Kosovo’s legal status remains at the heart of a dispute between Kosovo and Serbia. During recent years, talks between the two sides have included suggestions of a possible land swap. Under this proposal, the Albanian-dominated Preševo Valley in southern Serbia would become part of Kosovo while the area north of the Ibar river would become part of Serbia in order to create more ethnically homogenous states. Such swap is strongly opposed by nationalist and liberals on both sides (BBC, 6 September 2018). Located in northern Kosovo, the city of Mitrovica was socially, spatially and demographically divided during and after the Kosovo War and continues to be a fault line in the wider Serbia-Kosovo conflict. If the above land swap went ahead, Mitrovica would officially be divided between Kosovo and Serbia.

There is a growing literature on Mitrovica as a post-war city, centring on the partitioning of Mitrovica,Footnote2 boundaries and divisions in the cityscape,Footnote3 governmentality and urban conflicts over peace(s),Footnote4 statehood and place-making,Footnote5 and frictional peacebuilding.Footnote6 These studies tend to focus primarily on division in Mitrovica, and especially on the Main Bridge as the epicentre of interethnic violence, however in this article we argue that we can achieve a more nuanced understanding of how peace and conflict are intertwined in the post-war city by conducting a spatial analysis of the sites where communities live side by side in an otherwise segregated city. Further, we find that despite the overarching conflictual relations there are also strands of peaceful relations between Kosovo Albanian and Kosovo Serb residents in northern Mitrovica. Hence, we focus on the northern part of the city which is the home to the only multi-ethnic residential neighbourhoods in Kosovo in order to grasp the nuances and diversity such proximity provides.

The most easily accessible narratives about Mitrovica are those presented by politicians, in the media, and by international organisations, and these all emphasise the conflictual relations in the region. On the international level the region is in a state of ‘negative peace’, i.e there is an absence of war between Serbia and Kosovo, but much of the conflict remains unresolved, lacking true reconciliation. There is genuine conflict over territorial issues, war memories are kept alive, and the propaganda wars continue along with economic conflict actions manifested by tariffs raised to block imports of Serbian goods to Kosovo.

Nonetheless, in relation to many other post-war cities which still face a high level of armed violence, Mitrovica is comparatively less violent. Moreover, in parallel to narratives of conflict, there are also alternative narratives, which however may be less loud or vocal. The purpose of this article is to investigate the narratives of those people with few links to international donors who live or work in northern Mitrovica and how theydescribe interethnic relations across different sites in the city. We find that despite the unresolved conflict between Kosovo and Serbia, and flares of violence in the post-war city, there are at the same time strands of peace at the societal level. Thus we find that even in spaces in northern Mitrovica where a history of violence is entrenched, the situation can seldom be reduced to be seen only as purely conflictual; rather, these ‘hotspots’ often prove to be spaces where reproduction of peace – however quotidian – also occurs at the same time. This duality points us to the true complexity of the realities of peace in post-war regions – where remnants of war and potential for a co-existing peace often overlap and are sometimes intrinsically intertwined. A key finding is that the most conflictual residential areas in northern Mitrovica also are places where what we call peace acts, peace perceptions and peace issues are found. This is not to say that there is no animosity at the local level between Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs, but such animosity is often seen by our interviewees as being fuelled by elites or as a reaction to regional events, such as developments in transitional justice processes and international sports games.

The article is structured in the following way. First, we briefly discuss our theoretical point of departure and the methodology employed for the study. Then, we give a brief background to the conflicts in Mitrovica. Next, the empirical case study begins with a section on the spatial distribution of conflict and contestation in northern Mitrovica in general before we present and discuss three residential areas in more depth. In the concluding section we summarise our findings.

Understanding conflict and peace in post-war cities

This article studies the manifestations of both conflict and peace.Footnote7 The primary level of analysis is the everyday interactions between communities; however, such interactions are not isolated from events and actions at the political level. McConnell et al argue that peace as experienced by residents may be understood as ‘a fragile and contingent process that is constituted through everyday relations and embodiments, which are also inextricably linked to geopolitical processes’.Footnote8 This is indeed true in the case of many deeply divided post-war cities as they often ‘provide a battle zone for larger proxy wars initiated and orchestrated by agents whose interests extend beyond the municipal boundaries’Footnote9 and where there are established ‘urban frontiers’.Footnote10

For McConnell et al, the concept of everyday peace is closely related to the actions and practices of individuals, groups, institutions, and other actors in (re)producing peace. This notion of the ‘everyday’ in post-war environments refers to the ways in which people cope by whatever means they have to make ‘their lives the best they can’.Footnote11 Williams highlights how using everyday peace as a theoretical point of departure ‘offers an analytical framing for understanding how peace as a sociospatial relation, is reproduced through and against different sites’.Footnote12 A key presupposition in this view is that peace is an inherently political process, formed through the creation of both dissimilarities and connections as well as being ‘assembled and negotiated through different techniques of power’.Footnote13 While this approach helps us to identify what people view as conflict and peace, in this article we also aim to theorise in more detail the content of the conflictual and peaceful interactions. However, the existing definitions of peace beyond the absence of war are not well conceptualised and the specific meaning and constituent component are rarely analytically clear.Footnote14 In one of the more fully theoretically developed articles, Höglund and Söderberg Kovacs aim to capture the diversity of peace in societies where peace agreements have been reached. Their model builds on Galtung’s conflict triangle and outlines different types of post-settlement peace based on behaviour, attitudes and contested issues.Footnote15 The work by Höglund and Söderberg Kovacs is useful for understanding the problems in these societies and the shortcomings of peace, but even this framework does little to conceptualise peace itself, what it is and what it consists of. A new framework on peace as relationships, developed by Söderström, Åkebo and Jarstad provides theoretical components of real world peace which is more than just the absence of war, in order to allow description and analysis of different types of peace across all analytical levels and over time. Relational peace between two actors means that the two actors are interdependent on each other and do not use physical violence against each other. The framework identifies the presence of behavioural interaction as key to peace and postulates two forms of peaceful relation. The first type is legitimate coexistence which entails deliberation and mutual recognition. There is no obligation to collaborate or cooperate but simply an acceptance of the existence of the other as a legitimate other with which one can interact. The second type is friendship peace which suggests a higher degree of intimacy and trust, as well as some form of cooperation.Footnote16 Our work builds on this framework by focusing on where, how, and why both conflict and peace are present in different everyday settings in northern Mitrovica and charting both hostile and peaceful attitudes, behaviour and issues between Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs.

The article is based on Segall's fieldwork conducted in Mitrovica between October and December 2017 including informal conversations, field notes and 15 in-depth interviews. We purposefully selected respondents who were working and/or living in Mitrovica at the time of the study, and whose work or function was directly related to community representation and relations (i.e. municipal political candidates, community representatives, NGO workers). The interviewees include members of several Kosovo communities: Kosovo Serbs, Kosovo Albanians, Kosovo Bosniaks, Kosovo Goranis, and Kosovo Turks. None of the interviewees were directly affiliated with international organisations or foreign missions in Kosovo. The latter selection criterion emanates from our desire to focus on local voicesFootnote17 to complement the views of those employed by international organisations in our primary and secondary sources which often reflect the liberal western notion of peacebuilding. The study covered the entire urban and suburban area of Mitrovica north of the Ibar River, however the present article focuses on three sites in Mitrovica north of the river Ibar that were considered particularly contested ‘hotspots’ for violence by respondents and in municipal planning.

Situating the study

Over history, Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs have been oppressed at different times by the rulers from the other group, although there have also been times where every day peaceful relations have taken place. When the areas were Yugoslavia, members of different communities worked together in the mining industry and Mitrovica had the highest rate in the whole country of Serbs that were proficient in the Albanian language.Footnote18 Although inter-communal marriages were rare in comparison to other Yugoslav cities,Footnote19 residential neighbourhoods were often mixed and children from different communities attended the same school facilities, albeit in separate classrooms.Footnote20 Animosities between Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians surfaced after the death of Tito and in 1989 Kosovo lost the autonomous status which had been granted under the 1974 Yugoslav constitution. After a period of ever-increasing violence, hostilities between the Kosovo Albanian guerrilla force, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA, in Albanian UÇK: Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës), the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the Serbian police, and paramilitary groups escalated into outright war in 1998. The armed conflict ended in June 1999, and Kosovo became an international protectorate under UN auspices by approval of the United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1244. The resolution postponed the settlement of Kosovo’s legal status and in February 2008, Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence – an action that remains contested by Serbia.Footnote21

Some of the worst destruction in Mitrovica happened after the NATO bombing campaign ended in June 1999Footnote22 as violence, looting, and house burnings forced thousands to leave their homes.Footnote23 In light of this widespread violence, the French KFOR (Kosovo Force led by NATO under a UN mandate) set up checkpoints on the bridges in the middle of the town, an action which contributed to cementing the immediate post-war division of the city.Footnote24 For many years, it was impossible to travel between north and south without being accompanied by KFOR.Footnote25 Today, two bridges are open for both pedestrians and vehicles (the Eastern Bridge and the Suhodoll/Suvi Do Bridge), while the Main Bridge and the small ‘walking bridge’ are only open for pedestrians.

Two decades after the end of the war, the city of Mitrovica in northern Kosovo still remains largely residentially segregated. The southern municipality has around 72,000 inhabitants, and the vast majority are Kosovo Albanian; in 2015 only 14 inhabitants in this half of the city were Kosovo Serbs.Footnote26 The northern municipality has population of about 29,000 including around 4,900 Kosovo Albanians who mostly live in the western outskirts of the city.Footnote27 In the south, the currency is the Euro while in the north people generally use Dinars. The two sides of the city have different country codes and people who move between them often carry two cell phones or two SIM-cards in one phone.

Despite this virtual segregation, Mitrovica is the only place in Kosovo where members of the Kosovo Serb and Kosovo Albanian communities meet outside of international workplaces on a daily basis.Footnote28 In fact, Mitrovica’s northern part is home to the only truly multi-ethnic neighbourhoods in Kosovo.Footnote29 This physical proximity between different groups makes it possible to take the city as a focus for the empirical study of everyday interactions between groups which of course would not be possible in places where there is no inter-community contact.Footnote30

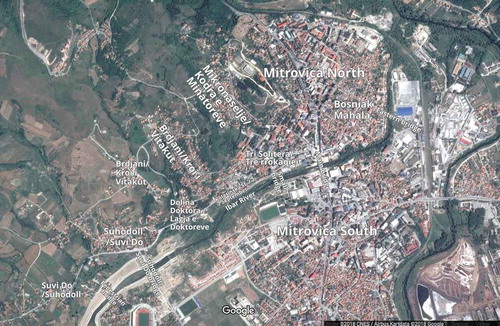

The English names of these areas are Bosniak Mahala (in Serbian: Bošnjačka Mahala and in Albanian: Lagjja e Boshnjakëve), Miner’s Hill (in Serbian: Mikronaselje and in Albanian: Kodra e Minatoreve), Three Towers (in Serbian: Tri Solitera and in Albanian: Tre rrokaqiejt), Doctor’s Valley (in Serbian: Dolina Doktora and in Albanian: Lagja e Doktoreve). The areas Brdjani (in Serbian)/Kroi i Vitakut (in Albanian), and Suvi Do (in Serbian)/Suhodoll (in Albanian) have no English translations.Footnote31 The map also shows bridges and other locations mentioned in the article.

shows a map of northern Mitrovica. The Main Bridge is Mitrovica’s most publicised locality and a highly symbolic site which is contested by both sides. Regarded as a flashpoint throughout the post-settlement years, the bridge is still constantly under watch by the Carabineri (Italian military police) and Kosovan Police force.Footnote32 During regional events such as sports games between Serbia and Albania, Turkey, or Kosovo there are frequently incidents on the bridge, such as young Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs throwing stones at each other.Footnote33 In a 2017 survey, Mitrovica citizens were asked about their feelings with regards to using the bridge, and a total of 60 per cent of respondents replied that they felt uncomfortable, threatened or exposed when crossing it, while 24.3 per cent said they felt normal, and 15.7 per cent stated that they never cross it.Footnote34 One respondent in our study, a Kosovo Albanian woman described how she and her friends always accompany each other to the Main Bridge after dark as they live on opposite sides of the river. She then goes on to explain how the respective zones of safety for herself and her friends shift as soon as they reach the bridge:

Some of my closest friends are Serbs (…) we always walk each other up to the bridge at night. I leave them by the bridge when we have been out in the south, and they always escort me up to the bridge if we have gone out in the north. It’s an act of caring and being worried about your friends’ well-being, but you are limited at the same time, because one step further can be dangerous sometimes, especially by night, one step is enough to reverse the roles at the bridge, if you know what I mean (…) Frankly, that’s why we stop exactly at the bridge and do not escort each other further, it’s because when I escort my friends, I cannot proceed, as there is where my safety ends, and theirs begins and vice versa. It’s also a bit paradoxical, when one really thinks of it. Footnote35

This act of caring and friendship is an example of a story seldom told about Mitrovica. It is an instance of mutual trust, a reciprocal act that is only limited by the boundary that the bridge poses after nightfall. This border exists even for those who pass it problem-free in daylight on an everyday basis.

Members of the two groups in Mitrovica generally have limited everyday contact and the city is often portrayed by outside observers as an extremely polarised context. Nevertheless it is worth pointing out that according to a 2014 community attitude survey, the vast majority of Kosovo Serb and Kosovo Albanian residents (73.9 per cent) would accept a member of the other group as a friend. Similarly, in Mitrovica South a total of 72.3 per cent stated that they would agree to having a boss who is a member of the other community, and in Mitrovica North a total of 63 per cent said they would accept such an arrangement in their workplace.Footnote36

The urban and suburban area of Mitrovica north of the Ibar river are rather diverse, despite the relatively small size in terms of population and territory. For instance, in the centre of the northern part of the city Serbian flags hang in the pedestrian area and the roundabout has a statue of Serbian icon Tsar Lazar at its centre,Footnote37 and this is perceived as a place where the Kosovo Albanian community would be hesitant to go.Footnote38 In contrast, on the street that runs parallel to the river towards the Western parts of the city (7 September/Kolašinska Street) you can find bilingual signage on shops and graffiti points to the presence of both Kosovo Serb and Kosovo Albanian communities. This is also where the Tri Solitera high-rises are located, three buildings which are home to members of both groups.

Miner’s Hill is another northern area which is home to members of both communities. In this neighbourhood, the communities live in close proximity to one another. Children here have shared the playgrounds in this neighbourhood since the immediate post-war years,Footnote39 and they also play football together.Footnote40 While most Kosovo Albanians in the north seek medical care in the south, there is a small health facility in Miner’s Hill where since Yugoslav times a doctor has attended to members of all communities in the neighbourhood.Footnote41 Similarly, while most Kosovo Albanian children go to school in the southern municipality, there is a small Albanian-language educational facility with some 18 pupils in Miner’s Hill.Footnote42 In our interview, one Kosovo Serb resident of this neighbourhood described the level of interaction between the residents in Miner’s Hill as follows: ‘we never had some kind of conflicts, I know that they are Albanians, I don’t have connections with them, they don’t have connections with me (…) we are like “hi”, “hello”, that’s all, because they respect me I respect them’.Footnote43 Similar accounts of co-existence have been voiced by residents in other research and documentary material on community relations in Miner’s Hill, and residents in the area also organised meetings between representatives from both communities in the immediate post-war years.Footnote44

While the areas close to the river and Tri Solitera are places where interactions between Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs take place, our interviews show that there are three neighbourhoods where peace and conflict are particularly intertwined in slightly different ways. Thus, this article focuses on the centric residential and commercial neighbourhood of Bosniak Mahala; the area of Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut on the Western hills on the outskirts of the city: as well as the Suhodoll/Suvi Do and Doctor’s Valley areas which are located on the Western outskirts of the city, with residents mostly living along the road parallel to the river Ibar. The sites were selected based on the criterion that they are residential neighbourhoods where both Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians reside.

Bosniak Mahala: the paradox of insecurity and ‘normalisation’

The Bosniak Mahala neighbourhood stretches from the Main Bridge beyond the Eastern Bridge in northern Mitrovica, and is home to several communities, including Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs. The Eastern Bridge is the most frequently used bridge in the city and some see this as a bridge that connects rather than divides the two sides.Footnote45 After the war, Bosniak Mahala suffered the most serious violent incidents and saw the largest number of casualties in the whole of Mitrovica.Footnote46 As it was located on the banks of the Ibar, in early 2000 the area became part of the confidence zone established by UNMIK and controlled by the French KFOR.Footnote47 Given its mixed population and its proximity to the river it became a strategic site after the war. According to one respondent, a representative of the Kosovo Bosniak community: ‘they wanted to make a buffer zone … because extremes were coming from both sides, we had a confidence zone, and then there was the attempt to ethnically cleanse this zone. (…) the biggest and the most serious incidents were in Bošnjačka Mahala. And the biggest number of victims, casualties, was in Bošnjačka Mahala’.Footnote48

Today, Bosniak Mahala is perceived as one neighbourhood with a particular high level of conflictFootnote49 and this can also be observed in the cityscape. Here ethnically charged murals are more pronounced and offensive and written on top of each other. Whenever there is a violent incident in close proximity to the Main Bridge, a revenge fight often takes place in other neighbourhoods, particularly in Bosniak Mahala.Footnote50 This area is considered to be particularly unsafe at night, especially because of a lack of police presence.Footnote51 However, there is also the belief that the situation in Bosniak Mahala has improved, mostly due to the efforts of citizens in this residential neighbourhood.Footnote52 At the same time, it was emphasised that the truth about many incidents seldom surfaces and that violent incidents may be framed as inter-ethnic even when it is related to something else, such as debt or crime.Footnote53

Bosniak Mahala is the area which shows the most obvious signs of mixing. For instance, licence plates continue to impede travels between north and south; someone with a KM-registered car (from Kosovska Mitrovica, a licence plate issued by Serbia) would never drive to the south for fear of provoking violence while those with a RKS car (Republic of Kosovo) are wary of showing their plates in the north. While this matter has been resolved in theory, in practice it is still problematic and many people therefore stop at the Eastern Bridge or further up on the Knjaza Miloša/Princi Millosh Street to either change licence plates as they go in whichever direction, or remove them entirely, going from the south to the north. People thus stop to change their licence plates in Bosniak Mahala, and both licence plates are seen here, so as such this can be said to be a place where such duality is tolerated. Another example of compromise shown in this neighbourhood concerns the show of flags. For Albanian flag day, celebrated on 28 November 2017, flags were hung along the lamp posts on the Eastern Bridge all the way through the first intersection on the northern side on the lower part of Knjaza Miloša/Princi Millosh Street. Several weeks later, the Albanian flags remained in place, which was interpreted as a sign of tolerance by one respondent, a Kosovo Albanian NGO worker.Footnote54

There are plenty of other physical signs of co-existence in Bosniak Mahala; the shops commonly display their business names in both Serbian and Albanian, for example bakery (pekara/furra) and butcher shop (mesara/mishtore), while some prices are shown in Euros instead of Dinars. It is not uncommon to hear Serbian being spoken by people shopping for goods in shops which bear Albanian names. The level of trust between some of the vendors and clients was exemplified by one interviewee who overheard a conversation in a fruit and vegetable shop:

A Serbian comes and buys lots of veggies for his store in the north. Then he tells the Albanian owner ‘Hey, I’m getting all these tomatoes but I’ll give you the money when I sell them’. (…) and he says ‘don’t worry for the money, whenever you have it, you bring it to me’. And that was beautiful because right there you see some trust. They’re building some trust and that’s really important, to trust each other.Footnote55

These interactions may be characterised simply as engagement based on needs; however, even the smallest steps in inter-group contacts can be understood as acts of peace given the basic trust they require.Footnote56 Also, while respondents see the majority of these exchanges in Bosniak Mahala as merely shallow conversations on practicalities such as prices and features of the product at hand,Footnote57 there are instances when these encounters go beyond merely need-based factors and are described as friendship:

I ran into another Serbian who just came to buy something for his household there, from the north to the Bošnjačka Mahala, and I asked him ‘so why do you come here among all the stores over there?’ He said, ‘well the food is really fresh, vegetables are always fresh, prices are good, and I know the owner, he is my friend, so that’s why I come here’. Beautiful, you know? If that was my only story about Mitrovica, oh my God, life is beautiful, you know. So I think people sometimes really can (…) without prejudice, they can co-exist, but then you always have these extremists on both sides who are ruining their normal life.Footnote58

Similarly, there is a space in Bosniak Mahala where young people from all communities study and interact on an everyday basisFootnote59: the International Business College MitrovicaFootnote60 (IBCM). The language of instruction is English and speaking in English with us, one interviewee, a Kosovo Serb student council member described this context of everyday co-existence as unproblematic and distanced from problems associated with the conflict:

I have colleagues who are Albanians, Roma, they are Bosnians (…) and we are talking, there’s no problem, we are functioning very well (…) people are usually oriented on the studies and they are not looking on something that have happened twenty years ago. We are looking more in the future and how cooperation between each other can help us more, and try to actually profit out of that (…) while [my colleagues] were having break they go to drink a coffee and nobody asks them what is your ethnicity, and they have coffee, chatting. We are actually speaking a lot and we’re honest, we share the same problems the same issues, for instance, same taste in music and similar.Footnote61

According to this student, the International Business College has thus become a space where students experience frequent problem-free engagement. For instance, the faculty and student council also comprise members of different communities. In this sense, the college can be seen as a space where everyday peace acts take place. One Kosovo Serb interviewee continues:

[the school is] full of young students who have the same goal. They cooperate good, there’s no problems there. Why? You just need to create space where they will all pursue a common goal, or a huge company where all of them will get the salary at the end of the month and they will be happy. They will. Because when people were employed here and had monthly revenues they didn’t have time to think about this bullshit like, I will kill Albanian or I will kill Serb. They were friends because they were satisfied; they were able to provide money for supporting their families, on the other hand to be friends with everybody, and to, I don’t know, enjoy life in the end.Footnote62

In contrast, teenagers overall were considered a high-risk group in terms of feelings of animosity or hostility towards members of the other community. While many young people didn’t experience the war, negative attitudes towards the other community are often transmitted from older generations.Footnote63 One example of a project which actively addresses this problem is a neighbourhood committee of residents in Bosniak Mahala which tries to reduce quarrels between groups of teenagers. The committee organises for the teenagers to be taken out of the neighbourhood for a weekend to play sports and get to know one another. After this, the fights in Bosniak Mahala stopped and now these teenagers say hi to one another in the street.Footnote64

These examples from everyday life in Bosniak Mahala clearly demonstrate the paradox of insecurity and ‘normalisation’. Despite their fear of violence due to the unsolved conflict between Kosovo and Serbia, the interviewees also experience everyday peace. This normalisation is manifested by peace acts of communication, meetings and cooperation; expressed in peace perceptions such as tolerance and trust; and identified as peace issues, based on common ground in shared life goals and hobbies, as well as shared spaces in shops, school and work places.

Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut: co-existence despite (re)settlement policies

In the more suburban neighbourhood of Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut, the most contested issues relate to housing (re)construction, (re)settlement, and returns. Almost two decades after the end of the war, some houses are still in ruins. In Mitrovica as a whole, the overall return process has been modest with only a small number of returnees.Footnote65 In 2014, UNHCR figures suggested that some 6,945 Kosovo Serbs were still displaced from the south side of Mitrovica to the four northern municipalities, while some 7,121 Kosovo Albanians remained displaced from the northern municipalities to Mitrovica South.Footnote66

Returns to the Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut neighbourhood have been particularly difficult. After the war, only Kosovo Serbs remained in this area.Footnote67 When the reconstruction of houses began, the Kosovo Serb community demanded that any returns to Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut should be undertaken reciprocally – meaning that the authorities should facilitate displaced Kosovo Serbs to returning to their properties in the south at the same time.Footnote68 The Kosovo Serb residents also claimed that many of the intended Kosovo Albanian returnees had never been residents of the neighbourhood nor did they have valid construction permits. Tensions related to returns in this neighbourhood have fluctuated over the years, with repeated protests (from both sides) between the years of 2012 and 2015.Footnote69 The heart of the conflict is the fear of becoming a minority group surrounded by a majority, one Kosovo Serb CSO worker stated:

we are here at risk of being overpopulated or basically being subjected to the Albanian majority which we don’t want to be done, because we have seen what happened to Serbs south of Ibar who are subjected to the Albanian majority. So either they don’t exist, they were expelled. They didn’t return or their cattle and agricultural equipment is stolen on the daily basis. So, like, we don’t want that.Footnote70

The Kosovo Government holds that Serbia is trying to change the ethnic structure in the two areas of Suvi Do/Suhodoll and Brdjani/Kroi i VitakutFootnote71 and the north through illegal construction of apartment buildings.Footnote72 The Serbian Government has mirrored Pristina’s claims by saying that the Kosovo Government is attempting to ‘artificially change the demographic picture’ through ‘land usurpation and illegal construction’ in Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut and the entire northern Mitrovica region.Footnote73

One perception is that the latest protests in Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut were in fact largely orchestrated, as they ended so abruptly after just a few months – or that they were specifically a reaction to a statement by a Kosovo Albanian political party calling a new residential area, Sunčana DolinaFootnote74 in the neighbouring Municipality of Zvecan, ‘Serbia’s colonisation of the north’.Footnote75

In 2015, the two Mayors (Mitrovica South and Mitrovica North in the Kosovo system) called for mutual compromise and introduced a moratorium on construction in this neighbourhood and this helped relieve the tensions.Footnote76 News media recorded how the local government officials shook hands in the neighbourhoodFootnote77 and a working group was established to discuss these issues, including central and local level Kosovo government officials, as well as representatives of the communities in Kroi i Vitakut/Brdjani.Footnote78 In 2017, the violent conflict over housing (re)construction in Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut was viewed as having finished. One Kosovo Serb interviewee in 2017 explained how tension had been instrumentalised by politicians, and suggested that this tension was easily resolved by stopping the project of housing reconstruction:

both sides want to move people who never lived there. That is the biggest problem. So, when they want to resettle people, usually they want to resettle people who never lived there. (…) they are resettling people just maybe they need some additional votes for the elections (…) But these are political games that they play, and you know, they want to use, to change this ethnic situation in every way (…) Now when they don’t try to rebuild or to build new houses, both of the communities, you don’t hear about problems in Brdjani. There is nothing about Brdjani in the news, everything is normal. There is no even single incident happening in the Brdjani and people are living together, why? Because political attention is not anymore on Brdjani, it’s on something else.Footnote79

Several of the respondents perceived politics as the main obstacle to peaceful co-existence, enhanced inter-community cooperation, and improved neighbourhood communication. The interviews show that the general perception is that inter-community relations between the Kosovo Serb and the Kosovo Albanian communities in Mitrovica have improved in comparison to previous years, although it is still not satisfactory. Instances of cooperation are unusual and only take place on isolated occasions, related to issues that concern both communities. These matters tend to be related to infrastructural problems and not to conflictive issues. Politics and lack of trust between communities makes cooperation more difficult, but there are examples where this takes place, for instance when Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians came together to finance a new power supply in 2016.Footnote80 Moreover, other strategies were applied to maintain constructive relations, such as avoiding topics related to politics and more ‘charged’ issues. One Kosovo Albanian resident of the Kroi i Vitakut/Brdjani neighbourhood says:

They communicate, but not some tough topics, they discuss mainly about daily work (…) The people I know, both Serbs and Albanians, are good people. Most of the places I frequent and know people, it’s good, like, my circle, my neighbourhood, we speak freely. If I go elsewhere I don’t feel the same, other Serbs who live in neighbourhood never give me a reason to talk to them. The current state of relations is in between good and bad, I cannot say it is perfect but it is not the worst case.Footnote81

Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut is one of the places where the ruins are both material reminders and symbols of the unresolved issue of returns of Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians displaced during and after the war. The conflict manifests in the attitudes of fear of changed demography and becoming an ethnic minority in the area. Despite the tensions that the (re)settlement policies create, interviewees also describe everyday peace acts of communication such as refraining from talking about politics and the perception of peaceful co-existence.

Our interpretation of the responses by the interviewees is that in Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut there is, in parallel to the conflict, also a sort of co-existence that exists despite the resettlement policies. While there is a fear that an influx of new residents or the return of displaced persons would upset the delicate balance in the area, there is at the same time a functioning everyday peace which is manifested by peace acts of deliberation and compromises; expressed in peace perceptions such as acceptance of people of other ethnicities than your own as residents in the neighbourhood, and peace issues such as concerns for joint problems.

Suvi Do/Suhodoll and Doctor’s Valley: freedom of movement despite municipal boundary conflict

These two areas are in the West of the city and the residents of Doctor’s Valley live in close proximity to one another, while Suvi Do/Suhodoll is largely separated into two different settlement: one is seen as the Kosovo Albanian one (located closest to the northern urban centre) and the one further away from the city is regarded as the Kosovo Serb settlement. The Albanian-majority area in Suhodoll/Suvi Do is clearly demarcated in symbolic terms: through flag display (both Albanian and Kosovo flags), street signs in the Albanian language and in Kosovo format, and graffiti dominated by UÇK (KLA, the Kosovo Albanian guerrilla group during the war). Entering Suhodoll/Suvi Do from the south, visitors also see a concrete cylinder with ‘UÇK’ and the Albanian escutcheon with the two-headed eagle sprayed on it. On the other hand, the places where the Serbian settlement starts and ends are only subtly marked, just by the licence plates on the cars, the small health facility with a sign in Cyrillic, and the absence of street signs in Albanian.

Mitrovica’s institutional landscape is characterised by duplication of public service provision where both Serbian and Kosovo institutions provide services through separate systems.Footnote82 Some public services such as the university – the only institution that provides higher education in the Serbian language in Kosovo – and the hospital, are administered and financed by Serbia.Footnote83

Suhodoll/Suvi Do and Doctor’s Valley are also the site of a highly contested issue, namely, the municipal boundary between the Municipality of Mitrovica North and Mitrovica South in the Kosovo system. This boundary matters both for political representation and service provisions, but could also become the state boundary between Kosovo and Serbia should a land swap take place. Before the Ahtisaari Plan (Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement) was presented by the UN Special Envoy in 2007, the city was de facto divided but there was no formal political and administrative boundary. The Ahtisaari Plan paid particular attention to the Suvi Do/Suhodoll area and included a map which marked the municipal boundary north of the Ibar River, meaning that both the Doctor’s Valley neighbourhood and Suvi Do/Suhodoll were included in the southern municipal jurisdiction. However, no formal agreement has been reached between the Serbian and Kosovo governments, nor is there an agreement between the Mayors.Footnote84

The Kosovo Government argues that the municipal boundary as outlined in the Ahtisaari Plan should be the final one.Footnote85 The Government of Serbia, however, refers to another map found with the Kosovo Cadastral Agency which includes Suhodoll/Suvi Do in the northern municipality. In the local Kosovo elections in 2013, the Suhodoll/Suvi Do residents formed part of the northern municipality’s electorate.Footnote86 The Mayor of the Municipality of Mitrovica South has suggested that the demarcation is a non-issue by stating that the area effectively belongs to the southern municipality (KoSSev, 25 October 2015). In the local elections of 2017, the Kosovo Serb residents were registered as voters of the northern electorate,Footnote87 while members of the Kosovo Albanian community were registered as voters in the southern municipality.Footnote88 The Serbian Government argues that this means a de facto delineation was made as Kosovo Serbs were allowed to vote in the north and therefore insists on demarcating the area into a Kosovo Albanian part administered by the southern municipality and a Kosovo Serb part administered by the Municipality of Mitrovica North.Footnote89

The question of the municipal boundary is indeed profound and the stakes are high ranging from municipal electorates and representation in local governmentFootnote90 to notions of partitioning Kosovo – a proposal which was openly discussed in late 2018 when, as mentioned above, Kosovo and Serb politicians discussed a possible land swap (RFERL, 29 September 2018). Among both Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians there is a feeling that politicians are prioritising geo-political concerns and territory over citizens.Footnote91

Despite being in a contested area, the transition between the urban centre and the Suhodoll/Suvi Do area is seamless. Both people and cars move both ways, and even cars with KM (‘Kosovska Mitrovica’) licence plates drive through the Kosovo Albanian-majority part of Suvi Do/Suhodoll,Footnote92 while there is also a small health facility administered by Serbia in the Kosovo Serb majority part of the area. In the Kosovo Albanian-majority part of Suhodoll/Suvi Do there is a mosque that was built in 2016 and there is an Albanian-language primary school.Footnote93 Suhodoll/Suvi Do is indeed a grey zone and the strategies for ‘claiming’ and demarcating the area are also present in the linguistic landscape. In early 2017, street signs in the Albanian language and Kosovo format were placed in the Suhodoll/Suvi Do area (Radio televizija Srbije, 28 February 2017). According to local news media, some of the signs bore names of KLA soldiers. The signs were disputed by the Kosovo Serb community and removed shortly after they had been placed there. However, the representative of the Kosovo Serb community said actually, the signs had possibly been removed by members of the Kosovo Albanian community in order to avoid any neighbourhood conflict.Footnote94 In this sense, there seems to be instances when residents attempt to diffuse potential tensions in these adjacent settlements. In late 2017, there were no observable Albanian-language signs in the Serb-majority part of the town, however, in the surrounding areas there were street signs allocated by the Kosovo Government.Footnote95

Disentangling the nature of actual relations is a truly nitty-gritty task as there are often diverse accounts of the same neighbourhood, however our research suggests that there is a general sense that relations between Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians in this site have improved. One Kosovo Serb interviewee explained that people had been:

cutting each other’s telephone lines, water supply lines and whatever (…) and in the end they just realized that they are harming each other, not anybody else, like, if you cut my telephone, I will cut your water and that’s it. Simple problem and they stopped.Footnote96

In a similar vein, the Kosovo Albanian former head of the Suhodoll/Suvi Do neighbourhood council said that there had been no incidents for a decade, stating firmly that:

for the Serbian and Albanian community in Suhodoll, there are no interethnic problems for many years now. (…) in the last 10 years we didn’t have even the smallest incident. The cooperation is satisfactory, I don’t know how to say this, moving up and down through Suhodoll is possible either by foot or vehicles. We don’t have those problems. Our properties are defined, we don’t have this problem as well (…) I would like to openly say that the Albanian community and the Serb community in Suhodoll cooperate.Footnote97

Despite facing the highly contested issue of municipal boundaries, and living in an area where the proposed land swap would divide the residents between Serbia and Kosovo, the freedom of movement for both cars and people of different ethnicities along this road stands in bright contrast to other clearly ‘etched boundaries’ in the city, such as the Main Bridge and the Eastern Bridge.

Our conclusions concerning Suvi Do/Suhodoll and Doctor’s Valley is that there exists a sort of freedom of movement despite the conflict over the municipal boundary which affects representation in local government and would become an acute issue if the parties moved forward with a land swap deal. Hence, in parallel to the conflicts, peace is manifested by peace acts such as communication, deliberation and compromises. There are also peace perceptions such as co-existence based on tolerance, and a peace issue of freedom of movement; the transition between the urban centre and the Suhodoll/Suvi Do area is seamless and both people and cars move both ways.

Bringing it all together

It is paramount to emphasise that in the Mitrovica case violent incidents and publicising violence is also used to uphold divisions in the city, including the fabrication of so called artificial incidents.Footnote98 This is not to say that there are no animosities or violent incidents which are the result of strained community relations. One Kosovo Bosniak local-level politician and community representative stated that:

when it comes to that destabilization of the situation they have their own people on both sides where they raise the nationalism when necessary, but for the incidents occurring in the north such as like putting cars on fire, throwing hand grenades on the properties, it’s not conducted by ordinary citizens, there are groups which are paid to do so from both sides.Footnote99

We believe that in order to interpret and contextualise events in this post-war city, it is important to include this understanding and perspective on conflicts, contestation, and the occurrence of violence in Mitrovica, as expressed in the quotation. However, it is also imperative to consider the interests and potential gains surrounding the portrayal of both peace and conflict. For while we do not want to diminish the fundamental negative effects of conflict in Mitrovica, our research shows that alongside the conflict there are also multiple strands of everyday peace at the societal level. After a civil war, even everyday acts such as greetings can have a positive effect on interethnic relations and contribute to a sense of peace. In addition, respondents emphasised the fact that disagreements on the micro-level were quite normal and that most often these do not result in violent actions.Footnote100 Such everyday peace manifests parallel to sentiments of fear and distrust between Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs in Mitrovica. While tensions on the ground are exaggerated by top-down measures and political elites, the conflicts are not created by the elites alone, and some violent incidents are initiated from below.

Our research suggests that even in spaces in the city where a history of violence is entrenched, the situation can seldom be reduced to be seen only as purely conflictual; rather, these ‘hotspots’ often prove to be spaces where reproduction of peace – however quotidian – also occurs at the same time. In general, we can say that the places that are understood as most conflict-ridden or contested, are those that are home to mixed communities and which are also located on the edges of what are the boundaries of the urban settlement of northern Mitrovica. This could be interpreted as what Calame and Charlesworth have called boundary etching in contested cities:Footnote101 the Ibar river is the more obvious boundary in the wider dispute, but in fact micro-boundaries are also etched within mixed areas. However, this does not fully explain the peace as co-existence or friendship which we have encountered in the residential areas, in the sense that the boundaries do not simply become frontiers, but also function as shared spaces. There, people make efforts to maintain peace, but these are often impeded or limited by political events beyond the community level. Hence, violent behaviours and incompatible issues are easily ignited by both local and external actors, while what we call peace acts, peace perceptions and peace issues are seen as the embodiments of peace produced in these neighbourhoods.

summarises the embodiment of peaceful and hostile relations identified in northern Mitrovica. These categories of behaviour, attitudes and issues influence each other. Peace acts can take the form of casual communication, for instance in relation to trade in Bosniak Mahala, or cooperation on practical matters such as the power supply in Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut. While such contacts decrease social distance, there are also more profound peace acts of cooperation, for example, actively discouraging conflict behaviour by rivalry teenagers in Bosniak Mahala or introducing a moratorium on construction of new buildings in Brdjani/Kroi i Vitakut. Peace perceived as co-existence is characterised by casual communication on need-based matters of mutual concern and tolerance of ethnically charged symbols, whereas friendship is a more intimate relationship related to trust. Peace issues, such as a sense of common ground can take the form of shared life goals or hobbies. Spatiality and the build environment shapes the possibilities for peace to evolve. The instances of shared space in shops, work places and the international business school in northern Mitrovica allows for a web of interactions where people can transcend differences.

Table 1. The embodiment of peaceful and hostile relations in northern Mitrovica.

The interviews conducted for this study show competing narratives of peaceful and conflictual everyday relations in the mixed neighbourhoods in northern Mitrovica. These views were expressed by interviewees that were not directly affiliated with international organisations and foreign missions in Kosovo, thus we seek to complement other more well-known expressions on the relations in the region. This article has highlighted stories seldom told of peaceful co-existence and friendship amidst violence and tension and points to the political issues that threaten everyday peace. In particular, if the land swap took place and the border between Serbia and Kosovo was drawn through the city of Mitrovica, some people would feel forced to move and the possibilities for mixing and everyday peace in these particular areas would thus be gravely undermined.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Jarstad

Anna Jarstad is Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at the Department of Political Science, Umeå University and Professor at the Department of Government, Uppsala University (ORCID ID 0000-0001-8048-1868). Jarstad leads the Varieties of Peace research program (varietiesofpeace.net) funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Sweden, and a project on the interactions between international and local democracy initiatives funded by Swedish Research Council. Her research focuses on the nexus of democratisation and peacebuilding. Email: [email protected]

Sandra Segall

Sandra Segall is a Bilateral Associate Expert in Gender and Peacebuilding based in Bogotá, Colombia. She holds a Master of Science degree in Peace and Conflict Studies from Umeå University and has a bachelor’s degree in the same field. Previously, Sandra has worked in women’s rights and communications in Chile and New Zealand. In 2017 she was a graduate intern in Kosovo focusing on urban peacebuilding and was awarded the Olof Palme Memorial Fund Scholarship. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1. Given the fact that place names are highly contested, English names will be used throughout this paper. When there is no English alternative, the order of place names in Serbian and Albanian does not carry assumptions of whether an area is considered a Kosovo Serb-majority or a Kosovo Albanian-majority municipality or location. Place names in respondents’ accounts have not been modified.

2. Lemay-Hébert, “Multiethnicité ou ghettoïsation?”.

3. Pinos, “Mitrovica.”

4. Gusic, Contesting Peace in the Post-War City.

5. Björkdahl and Kappler. Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation.

6. Björkdahl and Gusic, “The Divided City.”

7. For an overview of the literature on conflict manifestations in the post-war city see the introductory chapter to this collection.

8. McConnell et al., “Introduction,” 11.

9. Calame and Charlesworth, Divided Cities, 11–12.

10. Pullan and Baillie, Locating urban conflicts, 20–21.

11. Roberts, “Saving Liberal Peacebuilding from Itself,” 369.

12. Williams, Everyday Peace? 190.

13. Ibid., 178.

14. See e.g. Davenport, Melander, and Regan, The Peace Continuum; Firchow and Mac Ginty, “Measuring Peace”; and Gleditsch, Nordkvelle, and Strand, “Peace Research”.

15. Höglund and Söderberg Kovacs, “Beyond the Absence of War.”

16. Söderström, Åkebo and Jarstad, Friends, Fellows and Foes.

17. Leonardsson and Rudd, “The “local turn”” 832.

18. Schwartze, ‘Symbols of Reconstruction,” 222.

19. Gusic, Contesting Peace in the Post-War City, chapter 5.

20. Later, as tensions rose, Serbian and Albanian children attended school in shifts (Interview with Kosovo Albanian civil society activist, 19 December 2017).

21. For the background to events leading up to the declaration of independence in 2008, refer e.g. to Glenny, The Balkans; Jarstad, “To Share or to Divide?” 227–242; Judah, Kosovo; and Malcolm, Kosovo, 2002.

22. See note 18 above.

23. Boyle, “Revenge and Reprisal Violence in Kosovo,” 199–201.

24. O’Neill, Kosovo: An Unfinished Peace, 45–46.

25. ESI, “People or Territory?” 4.

26. OSCE, “Municipality Profile Mitrovica South.”

27. Ibid.

28. See note 19 above.

29. Interview with Kosovo Serb public policy NGO activist, 30 November 2017, Mitrovica.

30. Mac Ginty, “Everyday Peace”, 558–559.

31. OSCE, “Kosovo Communities Profile,” 4. Mixed neighbourhoods (see ) are understood as settlements where members of the Kosovo Serb and Kosovo Albanian reside in the same area, it does not take into account other minorities such as Kosovo-Bosniaks, Kosovo-Roma, Kosovo-Turks, and Kosovo-Gorani.

32. Author’s observation 2017; HRW, “Failure to Protect,” 28.

33. Interview with Kosovo Serb public policy NGO activist. See note 29 above.

34. ADRC, Beyond the Bridge, 22.

35. Conversation with Kosovo Albanian NGO worker in mediation, 29 November 2017, Mitrovica.

36. Jovic, “A Survey of Ethnic Distance in Kosovo,” 265–266.

37. The statue of Tsar Lazar was inaugurated in the summer of 2016. Lazar was a medieval ruler from the fourteenth century and a symbol for Serbia’s armed struggle against the Ottoman Empire, the statue’s presence resulted in the square being rendered a violation of the Kosovo Constitution by the Kosovo Ombudsman (Ombudsman, Annual Report, 80).

38. Interview with Municipal Assembly member and shop owner in Mitrovica North, 7 December 2017, Mitrovica.

39. ICG, “Bridging Kosovo’s Mitrovica Divide,” 15; and Conversation with Kosovo Serb resident, 29 November 2017.

40. OSCE, “Skills for the Future.”

41. Interview with Kosovo Albanian director of a women’s rights association, 29 November 2017, Mitrovica.

42. OSCE, “Municipality Profile Mitrovica North.”

43. Interview with Kosovo Serb member of the student council at International Business College Mitrovica, 28 November 2017, Mitrovica.

44. ESI, “Mitrovica Past and Future,”; UNHCR, “Fresh Start for Mixed Community in Kosovo,”; and KIPRED, “Grass-Root Approaches to Inter-Ethnic Reconciliation,” 25–26.

45. In a recent survey on citizen movements across the north-south divide only 9.9 per cent of respondents stated that they had never used it (ADRC, Beyond the Bridge, 22); Interview with Project officer, 12 December 2017, Mitrovica.

46. Interview with Kosovo Bosniak Municipal Assembly candidate to the Municipality of Mitrovica North representing the political party Koalicija Vakat; member of the Council for Peace and Tolerance, 2 December 2017, Mitrovica.

47. Visoka and Beha, Clearing up the Fog, 24; and Interview with Kosovo Bosniak Municipal Assembly candidate, see note 46 above.

48. Interview with Kosovo Bosniak Municipal Assembly candidate, see note 46 above.

49. Interview with Kosovo Serb member of the student council, see note 42 above; Interview with project officer, see note 45 above; and Interview with Kosovo Serb public policy NGO activist, see note 29 above.

50. Interview with Kosovo Serb public policy NGO activist, see note 29 above; and Interview with Kosovo Bosniak Municipal Assembly candidate, see note 46 above.

51. Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, 8 December 2017, Mitrovica.

52. See note 46 above.

53. Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 45 above; and Interview with journalist at Radio Free Europe and Radio Television of Kosovo, 24 November 2017.

54. Conversation with Kosovo Albanian NGO worker in mediation, see note 35 above.

55. Interview with journalist, see note 53 above.

56. Simonsen, “Addressing Ethnic Divisions,” 306.

57. Interview with Kosovo Serb representative of the Youth Educational Club Sinergija, 6 December 2017, Mitrovica.

58. See note 53 above.

59. Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 50 above; and Interview with Kosovo Serb member of the student council, see note 43 above.

60. IBCM is registered as an international foundation. It is supported by external donors and was founded by a foreign NGO.

61. Interview with Kosovo Serb member of the student council, see note 43 above.

62. Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 51 above.

63. Interview with project officer, see note 45 above.

64. Conversation with Kosovo Serb resident, 5 December 2017.

65. Interview with civil servant in the Department of Local Communities and Returns, Municipality of Mitrovica North, 23 November 2017, Mitrovica.

66. OSCE, “An Assessment of the Voluntary Returns,” 6 (reference to UNHCR).

67. OSCE, “An Assessment of the Voluntary Returns,” 18; and Interview with civil servant in the Department of Local Communities and Returns, Municipality of Mitrovica North, see note 65 above.

68. ICG, “Serb Integration in Kosovo,” 24–25; OSCE, “Kosovo Communities Profile,” 12.

69. UNMIK, “Report of the Secretary-General,” 3–4; and OSCE, “An Assessment of the Voluntary Returns,” 17–18.

70. Interview with Kosovo Serb representative of the Youth Educational Club Sinergija, see note 57 above.

71. Office of the Prime Minister, “Implementation of the Agreement on the Removal of the Barrier.”

72. Office of the Prime Minister, “Brussels Agreements Implementation”, 11–12.

73. Vucic, Statement by H.E. Mr. Aleksandar Vucic, 6–7.

74. Sunčana Dolina (Sunny Valley) is a residential area under construction in the Kosovo Serb majority municipality of Zvecan. It is a project initiated by Serbia intended for some 1,500 people that were displaced from Kosovo to central Serbia (Office for Kosovo and Metohija, “Predstavlјen projekat izgradnje povratničkog naselјa ‘Sunčana dolina”).

75. Interview with Kosovo Serb public policy NGO activist, see note 29 above.

76. UNMIK, “Report of the Secretary-General.”

77. Balkans, “Sukob u Mitrovici.”

78. MCR, “Annual Bulletin.”

79. Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 51 above.

80. Interview with Kosovo Albanian Municipal Assembly Candidate to the Municipality of Mitrovica North, representing the political party ‘Vetëvendosje’, 5 December 2017, Mitrovica.

81. Interview with Kosovo Albanian Municipal Assembly candidate, see note 80 above.

82. Mijačić, Jakovljevic, and Vlaskovic, Municipal Administrations in North Kosovo, 1–4.

83. See note 42 above.

84. Map of Suhodoll/Suvi Do area. Addendum to the Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement (2007). The matter was supposed to have been solved in October 2015 through the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding on issues related to spatial planning documents, such as the Municipal Development Plans and zoning maps (EEAS, “WG Freedom of Movement/Bridge Conclusions”); and Interview Project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 49 above.

85. Office of the Prime Minister, “Brussels Agreements Implementation”, 17.

86. Office for Kosovo and Metohija, “Progress Report”, 19–20.

87. Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 51 above.

88. Interview with Municipal Assembly member, see note 38 above.

89. Office for Kosovo and Metohija, “Progress Report,” 27–28.

90. According to the Kosovo Law on Self Government (Law No. 03/L-040 2008), non-majority communities comprising at least 10 per cent of a municipality’s total population, should have a non-majority community representative as the Deputy Chair of the Municipal Assembly. The number of assembly members is based on the population size of the municipality: the Municipality of Mitrovica North has 19 municipal assembly members while the Municipality of Mitrovica South has 35 seats.

91. Interview with Kosovo Albanian civil society activist, 19 December 2017; and Interview with Kosovo Serb representative of the Youth Educational Club Sinergija, see note 57 above.

92. Author’s observation.

93. Author’s observation; OSCE, “Municipality Profile Mitrovica North”; and Interview with Kosovo Albanian community representative and former head of the Suhodoll/Suvi Do neighbourhood council of the Municipality of Mitrovica South, 10 November 2917, Mitrovica.

94. KoSSev, “Suvi Do.”

95. Author’s observation 2017.

96. Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 51 above.

97. Interview with Kosovo Albanian Suhodoll/Suvi Do Community representative, see note 93 above.

98. Interview with Kosovo Albanian civil society activist, see note 91 above; Interview with Kosovo Serb project officer at peacebuilding grassroots organisation, see note 51 above; and Interview with Kosovo Bosniak Municipal Assembly candidate, see note 46 above.

99. See above 46 above.

100. Interview with Kosovo Serb member of student council, see note 43 above.

101. Calame and Charlesworth, Divided Cities, 213–217.

Bibliography

- ADRC . Beyond the Bridge: The Symbolism, Freedom of Movement and Safety. Mitrovica, Kosovo: Alternative Dispute Resolution Center, 2017.

- Balkans, A. 2015. “Video: Sukob u Mitrovici.” March 20. Accessed January 20, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kVU8SxL6Fug&t=30s

- Björkdahl, A., and I. Gusic. “The Divided City: A Space for Frictional Peacebuilding.” Peacebuilding 1, no. 3 (2013): 317–333. doi:10.1080/21647259.2013.813172.

- Björkdahl, A., and S. Kappler. Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation: Peace, Space and Place. New York: Routledge, 2017. doi:10.4324/9781315684529.

- Boyle, M. J. “Revenge and Reprisal Violence in Kosovo.” Conflict, Security and Development10, no. 2 (2010): 189–216. doi:10.1080/14678801003665968.

- Calame, J., and E. Charlesworth. Divided Cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar, and Nicosia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. doi:10.9783/9780812206852.

- Davenport, C., E. Melander, and P. M. Regan. The Peace Continuum: What It Is and How to Study It. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190680121.001.0001.

- EEAS. European External Action Service. 2015.“WG Freedom of Movement/Bridge Conclusions.” August 25 /2. http://fer.org.rs/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/WG-Freedom-of-Movement-Bridge-Conclusions-25-Aug-2015.pdf

- ESI. European Stability Initiative. 2003. “Mitrovica Past and Future.” video. https://www.youtube.youtubecom/watch?v=eGn33dmfhYc.

- ESI. European Stability Initiative. 2004. “People or Territory?: A Proposal for Mitrovica.” Accessed January 3, 2018. http://www.esiweb.org/pdf/esi_document_id_50.pdf

- Firchow, P., and R. M. Ginty. “Measuring Peace: Comparability, Commensurability, and Complementarity Using Bottom-Up Indicators.” International Studies Review 19, no. 1 (2017): 6–27. doi:10.1093/isr/vix001.

- Gleditsch, N. P., J. Nordkvelle, and H. Strand. “Peace Research: Just the Study of War?” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 2 (2014): 145–158. doi:10.1177/0022343313514074.

- Glenny, M. The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-1999. New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

- Gusic, I. Contesting Peace in the Postwar City. Belfast: Palgrave, 2019.

- Höglund, K., and M. S. Kovacs. “Beyond the Absence of War: The Diversity of Peace in Post-Settlement Societies.” Review of International Studies 36, no. 2 (2010): 367–390. doi:10.1017/S0260210510000069.

- HRW. 2004. “Human Rights Watch.” Failure to Protect: Anti-Minority Violence in Kosovo, March. https://www.hrw.org/report/2004/07/25/failure-protect/anti-minority-violence-kosovo-march-2004#_ftn11

- ICG. International Crisis Group. 2005. “Bridging Kosovo’s Mitrovica Divide.” Accessed January 1, 2018. https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/balkans/kosovo/bridging-kosovos-mitrovica-divide.

- ICG. International Crisis Group. 2009. “Serb Integration in Kosovo: Taking the Plunge.” Accessed January 30, 2018. http://old.crisisgroup.org/_/media/Files/europe/200_serb_integration_in_kosovo___taking_the_plunge.pdf

- Jarstad, A. “To Share or to Divide? Negotiating the Future of Kosovo.” Civil Wars 9, no. 3 (2007): 227–242. doi:10.1080/13698240701478937.

- Jovic, N. “A Survey of Ethnic Distance in Kosovo.” In Perspectives of a Multiethnic Society in Kosovo, edited by J. Teokarević, B. Baliqi, and S. Surlić. Belgrade: Youth Initiative for Human Rights, 2015: 261–270.

- Judah, T. Kosovo: War and Revenge. New Haven: Yale Nota Bene, 2002.

- KIPRED. Kosovar Institute for Policy Research and Development. 2012. “Grass-Root Approaches to Inter-Ethnic Reconciliation in the Northern Part of Kosovo.” Accessed February 8, 2019. http://www.kipred.org/repository/docs/grass-root_approaches_to_inter-ethnic_reconciliation_in_the_northern_part_of_kosovo_628494.pdf

- Kosovo Law on Self Government. “Law No. 03/L-040 2008.” Kosovo Official Gazette. https://gzk.rks-gov.net/ActDetail.aspx?ActID=2530.

- KoSSev, Kosovo Sever Portal 2017. “Suvi Do: Table na albanskom postavila Južna Mitrovica. Rakić: Ovakve poteze nećemo tolerisati.” March 1. Accessed November 22, 2017. https://kossev.info/?s=Suvi+Do%3A+Table+na+albanskom+postavila+Ju%C5%BEna+Mitrovica.+Raki%C4%87%3A+Ovakve+poteze+ne%C4%87emo+tolerisati

- Lemay-Hébert, N. “Multiethnicité Ou Ghettoïsation?: Statebuilding International Et Partition Du Kosovo À l’Aune Du Projet Controverse De Mur À Mitrovica.” Études Internationales 43, no. 1 (2012): 27–47. doi:10.7202/1009138ar.

- Leonardsson, H., and G. Rudd. “The ‘Local Turn’ in Peacebuilding: A Literature Review of Effective and Emancipatory Local Peacebuilding.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 5 (2015): 825–839. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1029905.

- Mac Ginty, R. “Everyday Peace: Bottom-Up and Local Agency in Conflict-Affected Societies.” Security Dialogue 45, no. 6 (2014): 548–564. doi:10.1177/0967010614550899.

- Malcolm, N. Kosovo: A Short History, 2002. London and Oxford: Pan Macmillan, 1998.

- Map of Suhodoll/Suvi Do area. Addendum to the Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement. Digital Copy Retrieved from the Map Collection at the Dag Hammarskjöld Library. New York: United Nations, 2007.

- McConnell, F., N. Megoran, and P. Williams. “Introduction: Geographical Approaches to Peace.” In The Geographies of Peace: New Approaches to Boundaries, Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution, edited by F. McConnell, N. Megoran, and P. Williams, 1–28. London: I. B. Tauris, 2014.

- MCR. Kosovo Ministry of Communities and Returns. 2015. “Annual Bulletin.” Accessed February 1, 2018. http://mzp-rks.org/bilten/bilten_en.pdf

- Mijačić, D., J. Jakovljevic, and V. Vlaskovic. Municipal Administrations in North Kosovo: A Two-Headed Dragon in One Body. Mitrovica: Institute for Territorial Economic Development, 2017. http://www.lokalnirazvoj.org/upload/Report/Document/2017_08/Municipal_administrations_in_North_Kosovo.pdf.

- O’Neill, W. G. Kosovo: An Unfinished Peace. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002.

- Office for Kosovo and Metohija. Serbian Government. 2016a. “Predstavlјen Projekat Izgradnje Povratničkog Naselјa “Sunčana dolina”.” May 31. Accessed January 20, 2018. http://www.kim.gov.rs/lat/v1419.php

- Office for Kosovo and Metohija. Serbian Government. “Progress Report on the Dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina.” April 2016b. Accessed November 11, 2017. http://www.kim.gov.rs/doc/pregovaracki-proces/2.1%20Izvestaj%20okt-mart%202016%20EN.pdf.

- Office of the Prime Minister, Kosovo Government. “Brussels Agreements Implementation State of Play.” November 25 2015. Accessed January 23, 2018. http://www.kryeministri-ks.net/?page=2,252.2015b

- Office of the Prime Minister, Kosovo Government. 2015a. “Implementation of the Agreement on the Removal of the Barrier from the Bridge of Mitrovica.” October 19. Accessed December 20, 2017. http://www.kryeministri-ks.net/?page=2,9,5302

- Ombudsman, K. 2016. Annual Report 2015. http://www.ombudspersonkosovo.org/repository/docs/English_Annual_Report_2015_351292.pdf

- OSCE. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 2010. “Kosovo Communities Profile.” Accessed November 10, 2017a. https://www.osce.org/kosovo/75450?download=true

- OSCE. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 2015. “Municipality Profile of Mitrovicë/Mitrovica South.” Accessed November 12, 2017b. https://www.osce.org/kosovo/122118?download=true

- OSCE. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 2015. “Municipality Profile Mitrovicë/Mitrovica North.” Accessed November 12, 2017c. https://www.osce.org/kosovo/122119?download=true

- OSCE. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 2018. “Municipality Profile 2018 Mitrovicë/Mitrovica North.” Accessed February 7, 2019. https://www.osce.org/mission-in-kosovo/122119?download=true

- OSCE. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 2010. Skills for the Future, Understanding for the Present: OSCE Project Gives Kosovo Youth Brighter Outlook, October 26. https://www.osce.org/kosovo/74243

- OSCE. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 2014. “An Assessment of the Voluntary Returns Process in Kosovo.” Accessed January 10, 2018. https://www.osce.org/kosovo/129321?download=true

- Pinos, J. C. “Mitrovica: A City (Re)shaped by Division.” In Politics of Identity in Post-Conflict States: The Bosnian and Irish Experience, edited by É. Ó. Ciardha and G. Vojvoda, 128–142. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Pullan, W., and B. Baillie. Locating Urban Conflicts: Ethnicity, Nationalism and the Everyday. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Roberts, D. “Saving Liberal Peacebuilding From Itself.” Peace Review 24, no. 3 (2012): 366–373. doi:10.1080/10402659.2012.704328.

- Schwartze, F. “Symbols of Reconstruction, Signs of Divisions: The Case of Mitrovica, Kosovo.” In The Heritage of War, edited by M. Gegner and B. Ziino. Routledge: Oxon and New York, 2011.

- Simonsen, S. G. “Addressing Ethnic Divisions in Post-Conflict Institution-Building: Lessons from Recent Cases.” Security Dialogue 36, no. 3 (2005): 297–318. doi:10.1177/0967010605057017.

- Söderström, J., M. Åkebo, and A. Jarstad. 2019. Friends, Fellows and Foes: A New Framework for Studying Relational Peace. Umeå Working Papers in Peace and Conflict Studies, no. 11, ISSN 1654-2398 ISBN 978-91-7855-054-8.

- UNHCR. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2003. “Fresh start for mixed community in Kosovo.” Accessed February 7, 2019. https://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2003/5/3eba82774/feature-fresh-start-mixed-community-kosovo.html

- UNMIK. United Nations Mission in Kosovo. 2015. “Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNSC S/2015/579).” July 30. Accessed February 14, 2018. http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/55cb3b2e4.pdf

- UNMIK. United Nations Mission in Kosovo. 2013. “Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNSC S//2013/72).” February 4. Accessed February 14, 2018. https://unmik.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/old_dnn/N1321969.pdf

- Visoka, G., and A. Beha. 2013. “Clearing up the Fog of the Conflict.” Kosovo Foundation for Open Society. http://kfos.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/clearing-up-the-fog-of-conflict-ENG.pdf

- Vucic, A. Statement by H.E. Mr. Aleksandar Vucic, Prime Minister of the Republic of Serbia. United Nations Security Council/Republic of Serbia, United Nations, 2014.

- Williams, P. Everyday Peace? Politics, Citizenship and Muslim Lives in India. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2015.