ABSTRACT

This article analyses political and religious mobilisation in Sidon and Tripoli, both secondary cities struggling amidst deep social divisions, elite competition, and armed conflict during the contentious decade following the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri (2005–15). A central element in the sectarian and Islamic resurgence was discontent with the political and social decline of the Sunnis. The Syrian revolt magnified Sunni-Shia tensions and shifted the locus of contentious politics from the capital Beirut to secondary cities such as Tripoli and Sidon. In both cities, communal tensions spurred confrontations with the Army that were followed by closely contested municipal elections. By examining the urban ecologies of resistance, the article contributes to an understanding of how urban inequality, competitive clientelism, and Islamist (social) movements are intertwined and can explain why the political pathways and electoral outcomes differed and the implications for the understanding of religious-influenced politics. The city-level analysis testifies to the importance of contextual urban traits and political actors’ agency in influencing the popular support for state-oriented social movements and sectarian parties and as determinants of their electoral fortunes.

Introduction

This article analyses political and religious mobilisation in Tripoli and Sidon amidst deep social divisions, elite competition, and armed conflict during the contentious decade following the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in 2005. During the period under study the two cities underwent concurrent processes of religious mobilisation and Islamist revival spurred by the murder of Rafik Hariri, deepened by the Syrian conflict turned civil war (2011–present), and followed by armed confrontations with the Lebanese army. Tripoli and Sidon are Sunni-majority cities, yet with significant minority groups. The cities are Lebanon’s second and third largest respectively and as such can be referred to as secondary cities trailing the capital Beirut.Footnote1 Both are deeply divided cities with social and economic divisions, rampant inequality, entrenched clientelism and patronage politics (Knudsen Citation2017a, Citation2020). In both Sidon and Tripoli the Future Movement, the country’s foremost Sunni party, has a stake in controlling the Sunni electorate but has faced stiff competition from local patrons, urban elites, and charismatic preachers resulting in what can be analysed as competitive clientelism (Lust Citation2009). The 2016 municipal elections drew different responses from the Sunni electorates in the two cities which point to contextual and systemic factors in deciding electoral outcomes that are analysed in the conclusion.

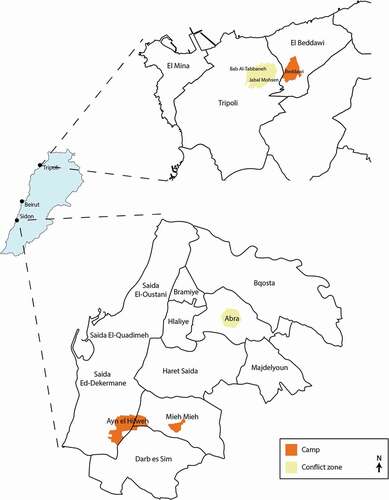

Tripoli and Sidon struggle with high unemployment, rapid urbanisation and economic decline in the shadow of the capital Beirut (Calame and Charlesworth Citation2009). Deeply divided, the cities’ dense urban core have become breeding grounds for identity and sovereignty conflicts (Pullan and Baille Citation2013; Davis and de Duren Citation2010). Tripoli is marred by communal conflict between the Sunnis in Bab al-Tabbaneh and Alawites in Jabal Mohsen, poor inner-city enclaves separated by army deployment (). In 2014 the conflict subsided, paving the way for municipal elections in 2016 where local elites were trumped by new contenders. Sidon, the country’s third largest city, also suffers from internal tensions and violent conflict in Ayn al-Hilweh, a conflict-ridden refugee camp and hub for militant Islamist groups (). From 2011, the growth of a local Salafi movement, the Assir movement, made internal conflict escalate and led to a fateful confrontation with the army in 2013 where many soldiers and fighters were killed. This led to a backlash against the movement and the loss of popular and electoral support and local elites reasserting control. In brief this meant that in Tripoli the electorate rallied behind a local outsider who beat powerful contenders allied with the Future Movement, the country’s major Sunni party. In Sidon voters abandoned local contenders and threw their support behind the Future Movement which won a decisive election victory.

To understand why electoral responses and outcomes in Tripoli and Sidon differed, it is necessary to revisit two cities’ recent history and the rise of Islamist (Salafist) movements and sectarian sentiments. The concurrent conflict events and post-conflict elections allow a side-by-side comparison of the two cities over a decade, thus making a comparative analysis of election outcomes possible. In both cities a key element in the sectarian and Islamic resurgence was discontent with the political and social decline of the Sunnis that followed the assassination of Rafik Hariri in 2005. The deep political divisions over Syria’s complicity in the murder and tutelage of the country led to mass protests turned opposing political blocs known as ‘March 8’ and ‘March 14’ (Knudsen Citation2012).Footnote2 The onset of the Syrian revolt turned civil war deepened these divisions and increased sectarian tensions especially after 2012 when Hizbollah engaged militarily in the Syrian civil war.

The neo-liberal transformation of Middle East cities, to which the Lebanon’s post-war period is a prime example (Becherer Citation2005; Fawaz Citation2009), has engendered a new form of urban politics that Asef Bayat has termed the ‘city-inside-out’ (Bayat Citation2012). In neo-liberal cities of this type, the urban subalterns comprise both the poor and the middle class and is characterised by political mobilisation in the form of ‘street politics’. The neo-liberal transformations, Bayat argues, have created a new ‘urban ecology’ that shapes Islamist sentiments of the urban poor and middle class alike (Bayat Citation2007, 579). In the fractured urban realm, disparities have grown and the citizens suffer from inadequate infrastructure, poor service delivery, and deficient local governments (Bayat and Biekart Citation2009, 822), traits not limited to, but magnified in secondary cities. To this end the paper extends Bayat’s analysis by examining how specific elements of the cities’ urban ecology ‘niche’ – politics (clientelism), economy (poverty), and religion (Islamism) – shaped the growth of social movements and influenced voter sentiments and electoral fortunes. By employing Bayat’s urban ecology approach, the article aims to fill a lacuna in the urban politics literature and contribute to the understanding of election outcomes beyond capitals.

This article draws on extensive research and publication on post-civil war Lebanon and is based on intermittent fieldwork in Tripoli (2013, 2020) and Sidon (2017, 2020). The analysis builds on first-hand interviews with a range of local of interlocutors such as religious scholars, politicians, municipal council members, patrons, street leaders, former and current members and supporters. Due to the sensitive nature of the research, I relied on personal contacts to reach out to potential interviewees in both cities. Most of the interviews were recorded in Arabic with the help of assistants and collaborators, and later translated and transcribed either partially or fully. The paper is structured as follows: I first describe the changing nature of Islamist politics and the growth of Sunni sectarianism amidst entrenched clientelist politics in the two cities. This is followed by a discussion of how competitive clientelism influenced electoral politics and outcomes and the implications of urban ecologies for the analysis of religious-influenced politics.

Islamist politics

Salafism has a transnational reach, but the focus here is its local characteristics in Lebanon’s Sunni-majority cities Tripoli and Sidon (Pall Citation2013; Rabil Citation2014; Rougier Citation2015). Salafism as a political-religious ‘actor’ share traits with social movements (Pall Citation2018, 27) and can be analysed as a subclass of what has been termed new social movements (Wiktorowicz Citation2004). During the decade under study here, Salafism reoriented itself from a morality-focused and pan-Islamist stance, and by the mid-2000s entered a sectarian phase (Gade Citation2017, 193). This brought Salafism closer to Sunnism’s opposition to political Shiism. Salafi preachers now saw themselves as defending the true faith against the threat of the Shia in general and Hezbollah in particular (Pall Citation2018, 74, 81). This change is also consistent with the haraki branch of Salafism becoming dominant after 2010 (Rabil Citation2014, 10–11) and served to ‘Lebanize’ Salafism which brought it closer to Sunni sectarianism (Gade Citation2017, 193). This, which could be termed ‘neo-Salafism’, combines populism with sectarianism, which accounts for its broad-based appeal among Sunnis, especially after 2011, when the Syrian uprising turned civil war and increased sectarian tensions between Sunnis and Shias (Samaha Citation2013).

In Tripoli Salafism emerged as a social movement rooted in urban poverty zones and the Palestinian refugee camps as well as among the city’s youth. In Tripoli, the dissolution of religious authority and deep-seated conflict within the country’s highest Sunni authority (Dar al-Fatwa), together with the regional surge of jihadism had swelled the numbers of Salafists (Rougier Citation2015), that added a doctrinal layer to a communitarian conflict by branding opponents non-believers (takfiris). The Salafists were mobilised by the Syrian civil war and locally by the Alawites’ allegiance to the Assad regime, as well as being radicalised by new jihadist groups like Fatah al-Islam (Knudsen Citation2011), and more so after start of the Syrian revolt when the Nusra Front and Islamic State (or ‘Daesh’), gained a foothold in Tripoli (Rougier Citation2015), but the jihadist influence in Tripoli remained limited, with the internal conflict displaced to Syria (Gade Citation2017).

In Sidon neo-Salafism resonated with urban poverty, social inequality, and Sunni discontent serving to mobilise the urban poor and middle class (Knudsen Citation2020). From the late 1990s, a quietist turned neo-Salafist movement led by the local Sheikh Ahmad Assir, gained a local following in Sidon and rose to prominence in the wake of the Syrian civil war. The movement’s rapid growth was spurred by internal and external factors and combined an Islamist (Salafist) discourse with social protests over the Sunnis disempowerment and political decline. In the mid-1990s, Assir with the help of young members established the movement’s own mosque in Abra, about five kilometres east of the city centre ().Footnote3 The profound social and economic inequalities in the city, combined with the entrenched clientelism (UN-Habitat Citation2017) made the movement an outlet for channelling frustration and resentment, but without confronting or challenging the clientelist networks and local elites that many depended on for their livelihoods. Assir’s independent status and charisma attracted many people to the mosque and attending his sermons; “I loved the prayers there; there was a high spirituality in his prayers, especially during the [Ramadan] ‘Night of Destiny’.Footnote4 The fact that Assir did not pay allegiance to a local patron or religious authority, made his message attractive to many and mixed with the growth of Sunni sectarianism which made more people join the movement (Knudsen Citation2020).

Sunni sectarianism

The growth of sectarianism following the onset of the Syrian revolt in 2011 was significant because this is not linked to a particular programme, party or group but appealed to Sunni’s primordial identity and claim to political pre-eminence (Gade Citation2012). Lebanon is characterised by extremely low levels of social mobility (el Khoury and Panizza Citation2001, 13). This is one reason for sectarianism’s broad appeal to the Sunni middle class, feeling neglected by the state and their social mobility and economic aspirations frustrated by governance failure, clientelism, and corruption (wasta). Moreover, in Lebanon sectarianism is institutionalised, with sectarian quotas for parliament and key government posts that underwrites ‘a countrywide patronage system’ (Bassel et al. Citation2015,: 3).

The late prime minister Rafik Hariri (1944–2005) was Lebanon’s pre-eminent statesman (Baumann Citation2016) whose dominant position in Lebanese post-civil war politics and as leader of the Sunnis has been coined ‘Harirism’ (Meier and Rosita Di Citation2017). Following Hariri’s assassination in 2005 the political decline of the Sunnis caused sectarian tensions that deepened after the Syrian revolt. This also challenged the leadership of the Sunni community, with the urban party elite facing local contenders in Tripoli and Sidon. This also shifted the locus of contentious politics from the capital Beirut to secondary cities such as Sidon and Tripoli and involved a conceptual shift from elite politics to the street politics of the grassroots. Despite being a numerical majority in the country the Sunnis have since 2005 acted as if being a minority, spurred by their political disempowerment vis-à-vis Hezbollah and the Shia, as well as the regional stand-off between Sunni and Shia states embroiled in the ‘New Arab Cold War’ (Wehrey Citation2017, 3). Despite the (Sunni) Prime Minister’s wider powers in post-civil war Lebanon, Sunni politicians have failed to ensure equal state investment in Sunni communities outside Beirut which has caused widespread resentment among disenfranchised Sunnis in Tripoli and Sidon (Henley Citation2017, 301).

There is a strong in-group support for sectarian parties in Lebanon (Cammett (Cammett Citation2014, 123). The Sunnis have the highest in-group partisanship, but also the least political participation. This is consistent with the problem of mobilising them in electoral politics and the widespread use of strategic service provision and vote-buying to win closely contested elections and electoral seats. The Future Movement (Tayyar al-Mustaqbal) was founded in 2007 but, like most parties in the country, lacks party-like structures, program and organisation (ICG Citation2010). The person-centred (clientelist) politics and weak institutionalisation of the Future Movement makes it vulnerable to competition from independent Sunni preachers, politicians, and patrons who can mobilise the ‘Sunni street’ for electoral purposes. The Future Movement’s decline under Saad Hariri increased the void between the Sunni political elite and the grassroots and the only issue that unites them are their opposition to the Syrian regime and Hezbollah (Asfura-Heim, Steinitz, and Schbley Citation2013). Sunni leaders and patrons therefore must resort to a sectarian rhetoric to maintain the support of their base (as in Tripoli) or co-opt Salafist Islamist movements (as in Sidon).

Like the Future Movement, the Dar al-Fatwa, the country’s highest Sunni religious authority, has been stifled by lack of reform and calls for deposing the leader, Grand Mufti Muhammad Rashid Qabbani. Under Qabbani the Dar al Fatwa lost funding and influence spurring the growth of Sunni mosques, charities, and independent movements outside its control (Pall Citation2018, 66–67). Disliked and distrusted by many Sunnis, Qabbani promoted a singular and orthodox version of Sunni Islam that alienated many and gave rise to popular resentment, Islamic activism, and Salafi militancy in places like Tripoli and Sidon (Henley Citation2017, 301). The regional dominance of Beirut’s Sunni clerical families and their privileged access to high-ranking jobs and elite networks, added to the local disenfranchisement.

Political clientelism

Due to the problems of accessing public goods and services, many people rely on informal patron-client networks for the provision of goods and services, so-called wasta, a system that is entrenched throughout the Middle East and in Lebanon as well (Huxley Citation1978). Being excluded from wasta means being cut-off from benefit streams and services that poor households cannot otherwise access or afford. In pre-war Lebanon, the most common way of accessing wasta was by joining clientelistic networks controlled by an urban merchant elite of political leaders (Ar. za’im, pl. zu’ama). The Sunni zu’ama of Beirut offered help and services to families or individuals (Johnson Citation1985). In return for their help, their clients voted for them during the elections. In order to ensure that clients voted for their respective patrons and closed ranks behind them, the leaders’ employed strong-arm retainers whose main job was to recruit and control the clients (Johnson Citation1985). The civil war ended the reign of the traditional Sunni zu’ama of Beirut who were eclipsed by the new super rich business tycoon, Rafiq Hariri. Until his death, Hariri was the pre-eminent Sunni za’im not only of Beirut but of Lebanon itself. The fallout from Hariri’s assassination transformed Sunni Islamism and made it possible to extend the March 14 bloc’s influence in North Lebanon, following Syria’s troop withdrawal and weakening tutelage of the country (Rougier Citation2015, 58).

In Tripoli clientelism is entrenched and political patrons (zu’ama) control security, service provision, and access to public goods (Allès Citation2012). The city’s economic downturn in the shadow of Beirut has increased poverty and unemployment and forced citizens to rely on political patronage to access public amenities in short supply such as water, electricity, and jobs. The economic and social problems have radicalised the city’s youth, seeing Islamism as an alternative to the city’s failing fortunes, corruption, and mismanagement. In recent years, the number of a mosques and religious institutions has multiplied and intensified communitarian conflict (Samra Citation2011). Traditionally the city was controlled by notable Sunni families such as the Karamis, but post-civil war neoliberalism has pitted them against the new business elite – Mikati, Safadi, and Kabbara – who compete among each other and outside contenders, in particular Hariri’s Future Movement, for control of the city and its electorate (Vloeberghs Citation2012; Baumann Citation2012). The deep political divisions running through the city have hamstrung the 24-member municipal council, whose members are aligned with competing local leaders and national blocs (March 8 and March 14).

Tripoli’s historic centre is the poorest and densely populated area of Lebanon and scores lowest on all development indicators: birth rate, income, education, and literacy (UN-Habitat Citation2016). An estimated 225,000 live in Tripoli’s three municipalities – Tripoli, Mina, and Beddawi – where the cheap rents concentrate poverty in socio-religious enclaves with poor infrastructure, sewage, and water provision (). Poverty and lack of public services create a market for political patronage, compounded by sectarian animosity and civil war grievances (Gade Citation2019). Tripoli’s crumbling centre has become a poverty trap where the residents depend on political patronage to make up for the lack of state provisions, thereby increasing sectarian grievances and fuelling communal conflict. State absenteeism has enabled local politicians cum patrons to extend patronage networks and build private foundations that in their magnitude and range of services mimic state departments (Knudsen Citation2017a).

To bolster their influence, leaders and patrons invest money in welfare politics by establishing charitable foundations that in their range of services rival those of the state, and serve as clientelist tools that are used to create dependency networks among poor residents. One of the most sophisticated foundations is Mikati’s Azm’e Saade Foundation. Built in 1998, the foundation’s headquarters and branch office provide welfare relief to families with the help of own staff and volunteers (Knudsen Citation2017a). The importance of patron-client relations testifies to a change from an organic to a mechanic solidarity, that has changed honorific and trust-based relations to a transactional relationship where services are exchanged for money to the highest bidder. This has changed that nature of patron–client relations from static to dynamic (Gade Citation2012), resulting in the leadership among the Sunnis becoming transient and contested, indeed, ‘the Sunnis have many leaders … but no leadership!’Footnote5

Despite the Sidon’s seaside location, historic port and patrimony, the city has seen its fortunes decline amidst rampant clientelism. Sidon’s proximity to Beirut has made it an economic backwater while the fierce competition between political actors’ stalls development projects. The city is the administrative centre of the Governorate of South Lebanon comprising three districts (Sidon, Jezzine, and Tyre). The Sidon district includes sixteen municipalities one of which is Abra (pop. 13,300), the centre of the Assir movement. In the Sidon district one third live below the national poverty line of four dollars a day (UN-Habitat Citation2017, 6ff). Poverty is also rampant in the city’s two Palestinian refugee camps, Ayn al-Hilweh and Mieh Mieh (), the former the country’s most populous camp and with frequent conflict spilling across camp boundaries. The camp and adjacent areas are hubs for jihadist and Salafist groups engaged in armed conflict with secular Palestinian nationalist groups (Sogge Citation2021).

Like Tripoli, Sidon is characterised by strong systems of non-state and informal governance at the expense of the public authorities and includes political parties, associations, syndicates and, especially, influential families and individuals (UN-Habitat Citation2017). This includes notable families with a long of history of residence in Sidon, hence referred to as Saidawees. Until mid-2000s it was the Saidawee elites, notables, and person-centred political parties that dominated Sidon politics. Sidon is the hometown of the late Prime Minister Rafik Hariri (1944–2005), the party’s main power base and seat of family dynasty (Mermier and Mervin Citation2012). In the 2004 municipal elections, however, the election list supported by Hariri family was defeated by a list backed by Saidawees leading professional unions and local political parties (ICG Citation2010, 19).

The assassination of Rafik Hariri and the nationwide protests and international prosecution that followed (Knudsen Citation2012), made the Hariri family the city’s new powerholders. In Sidon, the late Hariri’s sister, MP Bahia Hariri, represents the Hariri Foundation, the Future Movement and leads a charitable network of more than twenty-two civil society organisations (Ghaddar Citation2016). This powerful clientelist network attracts local, national, and foreign funding for development projects in the city and can obstruct those of opponents.Footnote6 Compared to historical accounts of Sunni clientelism (Johnson Citation1985), the clientelist system in Sidon can be termed a bureaucratic network of family-based unions that has become an alternative to the state’s rudimentary welfare-system and keeps ‘citizens continuously indebted and dependent’ (Ghaddar Citation2016, 10).

Army crackdown

The Lebanese army is a multi-confessional entity and national symbol of unity and neutrality in a deeply divided country (Knudsen and Gade Citation2017b). The army is the state’s last resort amidst repeated government collapse and state failure, yet carefully protects its unaligned role. This has made the army stand back in local and international conflicts, in particular Hezbollah’s May 2008 takeover of West Beirut (Rougier Citation2015, 192), that shortly after spread to Tripoli and restarted the communitarian conflict between the city’s warring parties. In the coming years, the conflict fluctuated with the political tensions in the country and escalated after the onset of the Syrian revolt. In 2013, deadly car bombs and sectarian attacks made the army clamp down on warring neighbourhoods and arresting militia leaders (Gade Citation2017, 190). The army campaign was part of a security plan endorsed by the Future Movement but drew criticism of the army being Hizbollah-controlled, especially the army’s powerful intelligence branch (mukhabarat al-jaysh); ‘The mukhabarat controls the conflict and the militias’.Footnote7 The army also suffered defections from its ranks and kidnappings of soldiers by jihadist groups on the border with Syria (Gade Citation2017).

In Sidon, Assir from April 2012 started a series of political rallies in support of the Syrian people that was broadcast on national TV and made him a household name and the face

of the Salafist movement in Lebanon. By the end of 2012 Assir had garnered over 330,000 followers on Facebook and 65,000 on Twitter. Over the next year his actions grew more militant and confrontational by challenging and attacking Hizbollah; ‘He was bold. He said what others did not have the courage to say’.Footnote8 With tensions rising, the army deployed in Abra, where the mosque was also being watched over by members of the local Resistance Brigades (Sarayaa Muqawama al-Lubnaniya), a Hezbollah-affiliated militia and adversary. While armed guards patrolled the compound’s perimeters, inside Assir was receiving Sunni delegations urging him neither to step down nor surrender and lay down the weapons.Footnote9 This was one reason why Assir failed to heed the warnings from his own Shura council, pleading with him to deescalate the conflict. Assir, however, insisted that the army would support and protect them, as would Sunnis across the country (Knudsen Citation2020).

The fatal misreading of the situation and not ‘listening to the voice of the country’,Footnote10 was a major reason for the final round of conflict escalation that sparked a three-day confrontation with the army (23–25 June 2013) and turned the Abra compound into a disaster zone, killing twenty soldiers and injuring more than one hundred. About forty members of the Assir movement were killed and more than sixty taken into custody amidst charges of army brutality and torture as well as collusion between the army and Hezbollah. Having escaped from the scene, Assir was arrested two years later at the Beirut International Airport while attempting to leave the country. He was transferred to the notorious Roumieh prison where a military tribunal in 2017 awarded him the death penalty for his role in the events that led to the killing of army soldiers.

The Abra incident made Sidon’s peaceful reputation suffer and was followed by an economic downturn that hurt the local retail trade. In post-conflict Abra the compound lay deserted, the worshippers disappeared, and former supporters grew silent. Wanted by the authorities Assir’s closest aides went underground to avoid arrest, yet many were tried in absentia and received long prison terms. In Sidon, many of Assir’s supporters now withdrew their support, feeling that Assir had betrayed their trust and misled the city’s youth so that ‘after the [Abra] battle and the killing of the army soldiers, seen as a national symbol, people started disassociating themselves from the Assir narrative’.Footnote11 The movement was now weakened, and popular support only about ten per cent of the movement’s pre-conflict strength (Knudsen Citation2020).

Electoral politics

Clientelism’s challenge to democracy is one reason why Islamist movements do not seek power by the ballot and voter participation is low. As Lust’s (Citation2009, 126) research on competitive clientelism in the Middle East has demonstrated ‘people vote for candidates whom they believe can deliver services and who will direct those services to them. When citizens feel that candidates do not meet these conditions, they stay home from the polls’. This perspective not only explains rationale behind the voters’ behaviour but also the candidates’ ‘understanding elections as a business investment helps to explain which types of elites choose to become candidates’ (ibid.: 129).

In post-civil war Lebanon, party-based clientelism has remained important (Nizar Citation2001), in particular because political parties lack traits common to parties in most Western democracies; they have often had no ideology, have devised no programmes and have made little effort at transcending sectarian support, thus most of them have seen their support wane (El Khazen Citation2003). Another explanation for the weakness of political parties in Lebanon is the role played by ‘electoral lists’, a particularity of the Lebanese electoral system. Unlike parliamentary elections where different sects are allotted candidates in proportion to their share of the electorate, in municipal elections there are no sectarian quotas and winners are ranked according to the total votes they garner. The inclusion of powerful candidates is therefore more important for electoral outcomes than political programs and party manifestos. The first municipal elections were held in 1998 seeking to decentralise decision-making, yet voter participation has sunk ever since. The elections are held every six years, with Sidon and Tripoli having twenty-four council members each (). Individuals are restricted to both vote and run in the districts of their official town of origin, so-called ‘ancestral voting’ (Abu-Rish Citation2016).Footnote12

Table 1. Municipal elections in Sidon and Tripoli, 2016.

In Tripoli the institutionalisation of private political and communal power is made possible by municipal poverty and absence of adequate public services. This gives local patrons an edge in local elections through vote-buying, which is reflected in the electoral success of Tripoli’s wealthiest Sunni parliamentarians (Knudsen Citation2017a). From 2011 the Syrian conflict intensified the local power struggle between local (Najib Mikati) and national (Saad Hariri) contenders aligned with opposing national blocs ‘March 8’ and ‘March 14’ (Abu-Rish Citation2016). The Tripoli commune (caza) consists of three municipalities (Tripoli, Mina, and Beddawi) with a total of about 175,000 registered voters from all sects. The voter turnout in municipal elections is only about one fourth of this (), and subject to extensive vote-buying (Abu-Rish Citation2016). Due to the difficulty in mobilising Tripoli’s Sunnis in elections and avoid splitting the Sunni vote, the former adversaries Hariri and Mikati joined forces to bankroll the For Tripoli list which was also backed by a coalition of city notables, one of three main electoral lists contesting the 2016 elections (). The newcomer, the Tripoli’s Choice list, supported by the local strongman and former Justice Minister Ashraf Rifi, won 18 seats in the city council while the main competitor, the For Tripoli list, bagged the remaining six seats.

The Tripoli’s Choice’s evocative slogan, ‘Beware of the Anger’, drew support from dispossessed and discontented Sunnis who saw the Future Movement’s pragmatic alliance with Mikati as a shift towards Hizbollah and their pro-Syrian March 8 affiliates in Tripoli. This proved a powerful mobilisation tool as did Rifi’s critique of the dismal security and economic conditions in the city. The election results testify to collapse of the city’s political hierarchy and Hariri and Mikati’s dwindling legitimacy, losing elections despite having bankrolled and appointed many of the For Tripoli list’s candidates (Abu-Rish Citation2016).

Sidon is predominantly Sunni with about 84% of the registered residents, but there is a minority Shia community supporting local party affiliates of Amal and Hezbollah. Of about 60,000 registered voters in Sidon, less than half cast their vote in municipal elections (). In 2016, three main electoral lists contested municipal elections in Sidon. Sidon’s Development list was backed by the Future Movement with support from local patrons and the Lebanese branch of the Muslim Brotherhood (Jamaa al-Islamiyya). The main opponent, Voice of the People, was supported by coalition comprising the Popular Nasserist Movement, Amal, and Hezbollah. The third list, Sidon’s Freedom, was a new contender led by Ali Sheikh Ammar, a local politician supporting the Assir movement. Sidon’s Development list won the elections but lost almost a quarter of the votes obtained in the 2010 election (). Yet, because an electoral list can monopolise the council if its candidates receive the most votes (Abu-Rish Citation2016), the Sidon’s Development won all the seats in the municipal council.

The Sidon’s Freedom list came last with about two-thousand votes, consistent with the diminished public support for the Assir movement (). However, party officials involved in the elections cite vote rigging, throwing out ballots and voter intimidation as reasons for the poor showing of the Sidon’s Freedom list, with many withdrawing their candidacy following political pressure from Sunni contenders and the army security made the candidates “marginalise themselves and stop their involvement as result of the suffering and injustice they endured.Footnote13 This can also account for the declining voter turnout in Sidon and the diminishing support for the Future Movement covertly supporting Assir to mobilise Sunni voters, only to drop him when he turned against the army thus they ‘were with [Assir] if he succeeded but abandoned him when he failed’.Footnote14

In the 2010 municipal elections the March 8 and March 14 blocs campaigned against each other in a zero-sum electoral game, while in the 2016 elections pragmatic alliances across blocs were often used to win closely contested elections (Abu-Rish Citation2016). Consistent with national trends, in 2016 the Future Movement allied with March 8 affiliated candidates in Tripoli yet lost the Sunni vote to the Tripoli Choice list. In Sidon the March 14 affiliated (Sunni) groups won the popular vote and all the council seats, soundly beating the contenders affiliated with the March 8 bloc (). To understand why election outcomes differed, we need to consider the contextual factors. In Tripoli, the Future movement’s electoral alliance was person-centred and included independents aligned with the pro-Syrian March 8 bloc which alienated Sunni voters. In Sidon, the election coalitions remained party and bloc centred and therefore avoided splitting the Sunni vote (Abu-Rish Citation2016).

The low level of participation in elections with patrons buying single and bloc votes from Sunni urban quarters and their leaders means that the elections outcomes need not reflect voter sentiments, but result from competitive clientelism (Lust Citation2009). In addition to doctrinal proscriptions, this perspective also explains the disinterest of the cities’ Islamists in contesting municipal elections, instead becoming clients of co-religious groups and patrons on account of the religious capital they command (Pall Citation2018, 27). Additionally, election malpractices such as vote buying, voter, and candidate intimidation influence election results and diminish popular participation in elections, especially of non-Muslim sects (Maronites, Greek Orthodox) and minorities (Alawites in Tripoli). The election results testify to the importance of person-centred politics, with Rifi the embodiment of the Tripolitan ‘strong man’ while Saad Hariri reeling under the shadow of his late father, consistent with the personification of parties and movements with their leaders (El Khazen Citation2003). The Army’s clampdown on Sunni militias in Tripoli was endorsed by the Future Movement, while in Sidon the deadly attacks on the army, a national force rising above sectarianism, was blamed on the Assir movement, influencing election results and voter participation.

Conclusion

Sidon and Tripoli are secondary cities that have remained at the economic and political margins of the capital Beirut. In both cities clientelist networks are entrenched, with local businessmen-turned-politicians contesting elections, and in the process upstaging traditional elites to become new political patrons and leaders. In Tripoli, the murder of Hariri reignited latent sectarian conflicts and grievances that was followed by the onset of the Syrian revolt from 2011 and the army crackdown and arrest of militants and leaders during 2013–14. This also coincides with the conflict escalation in Sidon and rapid growth of the Assir movement that culminated with the fatal confrontation with the army in mid-2013 followed by a clampdown on leaders and members.

The city-level analysis points to the urban ecology as important for the trajectory of Islamist groups, and more so in secondary cities like Tripoli and Sidon where entrenched poverty and clientelism promote sectarianism (Sunnism) and Islamism (Salafism) serving as alternative outlets for protests silenced and co-opted by elites. The Assir movement’s rise and fall was shaped by the city’s growing religiosity and Sunni identity as well as the quietist and, later, Salafist influences that connected Sidon with Tripoli. The major transformation of the Assir movement came after 2011, when rising Sunni-Shia tensions following the war in Syria changed contentious repertoires from collective to conflictual. The fatal attack on the army and subsequent clampdown on the movement, prosecution, and imprisonment of the leader and aides led to the movement’s gradual dissolution and forced loyal cadre underground with the remaining loyalists supporting the political offshoot, the Sidon’s Freedom list. The attacks on the army diminished electoral support for Sidon’s Development list which despite trumping contenders, was blamed for not reigning in Assir.

In Tripoli, the historical centre of Salafism, internal divisions between the city’s Sunnis and Alwites led to embittered conflict involving street leaders, militias, and fighters with covert financial and political support from patrons and leaders. The army’s crackdown in 2014 halted the conflict, but targeted Sunni militias and street leaders with political support from the Future Movement seeking to retain a foothold in the city. This together with the support for candidates affiliated with the pro-Syrian March 8 bloc, cost the Future Movement dearly with a Sunni resurgence harnessed by the Tripoli’s Choice list sweeping the 2016 elections. The widespread electoral malpractice and competitive clientelism that characterise municipal elections, influence electoral outcomes and explain why Islamist groups do not contest elections and instead becoming clients of political patrons.

The analyses of the post-conflict elections in Tripoli and Sidon demonstrate that the person-centred (clientelist) politics and weak institutionalisation of political parties made them susceptible to competition from independent Sunni preachers and politicians but with different outcomes. These contextual factors point to the importance of the cities’ urban ecology to explain political and religious mobilisation and post-election outcomes. In both Tripoli and Sidon, the void between the Sunni political elite and the grassroots compelled traditional Sunni leaders and contenders to either resort to a sectarian rhetoric to maintain the support of their base (Tripoli) or co-opt Islamist movements (Sidon). In more general terms, this points to the importance of both contextual urban traits and the political actors’ agency in influencing the popular support for state-oriented social movements and sectarian parties and as determinants of their election fortunes.

Acknowledgements

This article draws on previous research and publication in Tripoli (Knudsen Citation2017a) and Sidon (Knudsen Citation2020), as well as sections contained in a project research note (Knudsen Citation2019). Editorial advice as well as comments and suggestions from two TWT reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. The revision process was supported by a publication grant from the Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI). The usual disclaimer applies.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Are John Knudsen

Are John Knudsen is Research Professor at the Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and holds a PhD in social anthropology from the University of Bergen (2001). Knudsen has been research director at CMI (2006–09, 2013–15), project manager for institutional research collaboration in Palestine (2005–13) and co-director of an institute program on Forced Migration (2009–13). Knudsen has completed long-term fieldwork and short-term assignments in Afghanistan, Lebanon, Pakistan, and Palestine and specialises in urban conflict, forced displacement, and Islamist politics in divided societies. Knudsen has broad experience from leading international research projects and teams. Knudsen’s research is funded by the Research Council of Norway (RCN), Nordic Research (NordForsk), and the European Commission (EC).

Notes

1. UN-Habitat defines a secondary city as an urban area with a population of 100,000 to 500,000, https://www.citiesalliance.org/how-we-work/our-themes/secondary-cities (accessed 7 April 2021).

2. The two blocs take their names from the dates of the mass demonstrations that followed Hariri’s assassination.

3. Former member, telephone interviews, 18 August 2019 august and 20 October 2017

4. Female supporter, interview, Sidon 15 February 2020.

5. Former politician, interview, Tripoli, 13 November 2013.

6. An example of the city’s governance crisis was the local Garbage Mountain (Jabal al-Zabeleh) that grew to become a public health hazard and environmental risk (UN-Habitat Citation2017).

7. Sunni activist, interview, Tripoli, 9 November 2013.

8. Senior Sunni scholar, interview, Sidon, 7 December 2017.

9. Former member, telephone interview, 18 August 2017.

10. Municipal Council Member, interview, Sidon, 7 December 2017.

11. Policy analyst, interview, Beirut, 10 December 2017.

12. The election law requires a man (and if married, his spouse) to vote in the voting district that corresponds to his/their ancestral origins, and not in the current place of residence.

13. Sunni politician, interview, Sidon, 21 February 2020.

14. Senior Sunni scholar, interview, Sidon, 7 December 2017.

References

- Abu-Rish, Z. 2016. “Municipal Politics in Lebanon “ MERIP 46 (Fall, 280):http://www.merip.org/mer/mer280/municipal-politics-lebanon.

- Allès, C. 2012. “The Private Sector and Local Elites: The Experience of Public Private Partnership in the Water Sector in Tripoli, Lebanon.” Mediterranean Politics 17 (3): 394–409. doi:10.1080/13629395.2012.725303.

- Asfura-Heim, P., C. Steinitz, and G. Schbley. 2013. The Specter of Sunni Military Mobilization in Lebanon. Arlington, VA: CNA Report. https://www.cna.org/cna_files/pdf/DOP-2013-U-006349-Final.pdf.

- Bassel, S., J. S. Rabie Barakat, L. W. K. Al-Habbal, and S. Mikaelian. 2015. The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon. London: Pluto Press.

- Baumann, H. 2012. “The ‘New Contractor Bourgeoisie’ in Lebanese Politics: Hariri, Mikati and Fares.” In Lebanon: After the Cedar Revolution, edited by A. Knudsen and M. Kerr, 125–144. London: Hurst.

- Baumann, H. 2016. Citizen Hariri: Lebanon’s Neo-Liberal Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bayat, A. 2007. “Radical Religion and the Habitus of the Dispossessed: Does Islamic Militancy Have an Urban Ecology?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 31 (3): 579–590. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00746.x.

- Bayat, A. 2012. “Politics in the City-Inside-Out.” City & Society 24 (2): 110–128. doi:10.1111/j.1548-744X.2012.01071.x.

- Bayat, A., and K. Biekart. 2009. “Cities of Extremes.” Development and Change 40 (5): 815–825. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01584.x.

- Becherer, R. 2005. “A Matter of Life and Debt: The Untold Costs of Rafiq Hariri’s New Beirut.” The Journal of Architecture 10 (1): 1–42. doi:10.1080/13602360500063089.

- Calame, J., and E. Charlesworth. 2009. Divided Cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar and Nicosia. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Cammett, M. 2014. Compassionate Communalism: Welfare and Sectarianism in Lebanon. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Davis, D. E., and N. L. de Duren. 2010. Cities & Sovereignty: Identity Politics in Urban Spaces. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press.

- El Khazen, F. 2003. “Political Parties in Postwar Lebanon: Parties in Search of Partisans.” Middle East Journal 57 (4): 605–624.

- el Khoury, M., and U. Panizza. 2001. Poverty and Social Mobility in Lebanon: A Few Wild Guesses. Beirut: Dep. of Economics, AUB, www.erf.org.eg/html/panizza_Elkhoury.pdf.

- Fawaz, M. 2009. “Neoliberal Urbanity and the Right to the City: A View from Beirut’s Periphery.” Development and Change 40 (5): 827–852. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01585.x.

- Gade, T. 2012. “Tripoli (Lebanon) as a Microcosm of the Crisis of Sunnism in the Levant.” BRISMES paper, http://brismes2012.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/gade-tine-lebanon-brismes-2012.pdf.

- Gade, T. 2017. “Limiting Violent Spillover in Civil Wars: The Paradoxes of Lebanese Sunni Jihadism, 2011–17.” Contemporary Arab Affairs 10 (2): 187–206. doi:10.1080/17550912.2017.1311601.

- Gade, T. 2019. “Together All the Way? Abeyance and Co-optation of Sunni Networks in Lebanon.” Social Movement Studies 18 (1): 56–77. doi:10.1080/14742837.2018.1545638.

- Ghaddar, S. 2016. Machine Politics in Lebanon’s Alleyways: The Century Foundation, https://tcf.org/content/report/machine-politics-lebanons-alleyways/

- Henley, A. D. M. 2017. ““Religious Authority And Sectarianism In Lebanon “.” In Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East, edited by F. Wehrey, 283–302. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Huxley, F. C. 1978. Wasita in a Lebanese Context: Social Exchange among Villagers and Outsiders. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

- ICG. 2010. Lebanon’s Politics: The Sunni Community and Hariri’s Future Current. Beirut and Brussels: Int. Crisis Group, Middle East Report No. 96, 26 May 2010.

- Johnson, M. 1985. Class and Client in Beirut: The Sunni Muslim Community and the Lebanese State 1840-1985. London: Ithaca Press.

- Knudsen, A. J. 2011. “Nahr el-Bared: The Political Fall-out of a Refugee Disaster.” In Palestinian Refugees: Identity, Space and Place in the Levant, edited by A. Knudsen and S. Hanafi, 97–110. London: Routledge.

- Knudsen, A. J. 2012. “Special Tribunal for Lebanon: Homage to Hariri?” In Lebanon: After the Cedar Revolution, edited by A. Knudsen and M. Kerr, 219–233. London: Hurst.

- Knudsen, A. J. 2017a. “Patrolling a Proxy-War: Soldiers, Citizens and Zu’ama in Syria Street, Tripoli.” In Civil-Military Relations in Lebanon: Conflict, Cohesion and Confessionalism in a Divided Society, edited by A. J. Knudsen and T. Gade, 71–99. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Knudsen, A. J. 2019. Sunnism, Salafism, Sheikism: Urban Pathways of Resistance in Sidon, Lebanon. Oslo: Nupi, HYRES Research Note, http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2599516

- Knudsen, A. J. 2020. “Sheikhs and the City: Urban Paths of Contention in Sidon, Lebanon.” Conflict and Society 6 (1): 34–51. doi:10.3167/arcs.2020.060103.

- Knudsen, A. J., and T. Gade. 2017b. “The Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF): A United Army for A Divided Country?” In Civil-Military Relations in Lebanon: Conflict, Cohesion and Confessionalism in a Divided Society, edited by A. J. Knudsen and T. Gade, 1–22. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lust, E. 2009. “Competitive Clientelism in the Middle East.” Journal of Democracy 20 (3): 122–135. doi:10.1353/jod.0.0099.

- Meier, D., and P. Rosita Di. 2017. “The Sunni Community in Lebanon: From “Harirism” to “Sheikhism”?” In Lebanon Facing the Arab Uprisings: Constraints and Adaptation, edited by D. Meier and P. Rosita Di, 35–53. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mermier, F., and S. Mervin. 2012. Leaders Et Partisans Au Liban. Paris: Karthala.

- Nizar, H. A. 2001. “Clientelism, Lebanon: Roots and Trends.” Middle Eastern Studies 37 (3): 167–178. doi:10.1080/714004405.

- Pall, Z. 2013. Lebanese Salafis between the Gulf and Europe: Development, Fractionalization and Transnational Networks of Salafism in Lebanon. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Pall, Z. 2018. Salafism in Lebanon: Local and Transnational Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pullan, W., and B. Baille. 2013. Locating Urban Conflicts: Ethnicity, Nationalism and the Everyday. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rabil, R. G. 2014. Salafism in Lebanon from Apoliticism to Transnational Jihadism. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Rougier, B. 2015. The Sunni Tragedy in the Middle East: Northern Lebanon from al-Qaeda to ISIS. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Samaha, N. 2013. “Lebanon’s Sunnis Search for a Saviour.” al-Jazeera International (15 June), http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/06/2013615115015272727.html

- Samra, M. A. 2011. “Revenge of the Wretched: Islamism and Violence in the Bab Al Tabaneh Neigbourhood of Tripoli.” In Arab Youth: Social Mobilization in Times of Risk, edited by S. Khalaf and R. S. Khalaf, 220–235. London: Saqi.

- Sogge, E. L. 2021. The Palestinian National Movement in Lebanon: A Political History of the ‘Ayn al-Hilwe Camp. London: I. B. Tauris.

- UN-Habitat. 2016. Tripoli: City Profile. Beirut. UN-Habitat, Lebanon. Tripoli: City Profile. Beirut: UN-Habitat, https://unhabitat.org/tripoli-city-profile

- UN-Habitat. 2017. Saida City Profile. Beirut: UN-Habitat, unpublished draft, 246 pages.

- Vloeberghs, W. 2012. “The Hariri Political Dynasty after the Arab Spring.” Mediterranean Politics 17 (2): 241–248. doi:10.1080/13629395.2012.694046.

- Wehrey, F. 2017. Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wiktorowicz, Q. 2004. Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press.