Abstract

Micromus angulatus (Stephens, 1836) belonging to Microminae of Hemerobiidae was newly recorded in South Korea in 2010. We report the complete mitochondrial genome in the subfamily Microminae. The circular mitogenome of M. angulatus is 16,153 bp including 13 protein-coding genes, two ribosomal RNA genes, 22 transfer RNAs, and a single large non-coding region of 1,488 bp. The base composition was AT-biased (89.5%). Gene order of M. angulatus is identical to Neuronema laminatum (Drepanepteryginae). Phylogenetic trees present that the two Micromus mitochondrial genomes of Microminae are distinct to the two mitochondrial genomes of Drepanepteryginae of Hemerobiidae and other families of Neuroptera.

A brown lacewing, Micromus angulatus (Stephens, 1836), belonging to subfamily Microminae of family Hemerobiidae, is an euryphagous predator which feeds on aphids, coccids, and mites (New Citation1975; Samson and Blood Citation1980; Navi et al. Citation2010). It is widely found in Holarctic regions including Korea, Japan, and China (Kim et al. Citation2010). Hemerobiidae (brown lacewings) as well as Chrysopidae (green lacewings) have been considered beneficial (New Citation1975; Garzón-Orduña et al. Citation2016) and evaluated as biological control agents for aphids (Sato and Takada Citation2004; Kim et al. Citation2013). Three species of Chrysopidae and Hemerobiidae, Chrysopa pallens, Chrysopela carnea, and M. angulatus have been commercialized as biological agents for aphids in Korea.

Despite about 560 species in 10 subfamilies in Hemerobiidae (Oswald Citation1993; Garzón-Orduña et al. Citation2016), only two complete and two partial mitochondrial genomes from two subfamilies are available: Neuronema laminatum (Zhao et al. Citation2016), Drepanepteryx phalaenoides (KT425087; Drepanepteryginae), Micromus sp. YW-2016 (KT425075; Microminae), and M. angulatus (KX670539; not accessible; Song et al. Citation2018).

Whole mitochondrial genome of M. angulatus was completed from DNA extracted using CTAB-based DNA extraction method manually (iNtRON biotechnology, INC., Korea). Samples were captured at Nonsan city, South Chungcheong province, Republic of Korea (36°12′25ʺN, 127°11′48ʺE) in 2008. DNA sample was deposited in National Institute of Agricultural Sciences of Rural Development Administration. Sequencing was conducted using HiSeqX (Macrogen Inc., Korea) with filtering with Trimmomatic 0.33 (Bolger et al. Citation2014). de novo assembly and confirmation were carried out using Velvet 1.2.10 (Zerbino and Birney Citation2008), SOAPGapCloser 1.12 (Zhao et al. Citation2011), BWA 0.7.17 (Li Citation2013), and SAMtools 1.9 (Li et al. Citation2009). Geneious R11 11.1.5 (Biomatters Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) was used to annotate mitochondrial genome based on those of Polystoechotes punctatus (NC_011278; Beckenbach and Stewart Citation2009) and N. laminatum (NC_028153; Zhao et al. Citation2016). ARWEN (Laslett and Canbäck Citation2008) was used to annotate tRNAs.

Micromus angulatus mitochondrial genome length is 16,153 bp (GenBank Accession Number: MK472073). Its nucleotide composition is AT-biased (A + T ratio is 80.0%). The mitochondrial genome contains 13 protein-coding genes, two rRNAs, and 22 tRNAs. Gene order of M. angulatus is identical to N. laminatum (Drepanepteryginae: Hemerobiidae; NC_028153; Zhao et al. Citation2016). tRNAs size ranges from 63 bp to 73 bp, and all except tRNA-Ser lacking dihydrouridine arm could be folded into a typical cloverleaf secondary structure; same to that of N. laminatum. COI and ND5 lack a complete termination codon in both N. laminatum and M. angulatus mitochondrial genomes. The control region, presumably corresponding to the single largest non-coding AT-rich region, is 1,488 bp (AT ratio is 89.5%).

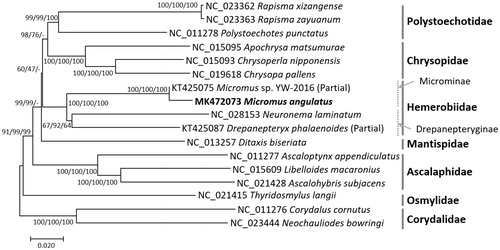

We inferred the phylogenetic relationship of seventeen Neuropterids complete or partial mitochondrial genomes aligned using MAFFT 7.388 (Katoh and Standley Citation2013). Bootstrapped neighbor joining, minimum evolution, and maximum likelihood trees were constructed using MEGA X (Kumar et al. Citation2018). Phylogenetic trees present that two Micromus mitochondrial genomes (Microminae) are distinct to the other two genomes in Drepanepteryginae (). In addition, Ditaxis biseriate (Mantispidae) is clustered with Hemerobiidae except maximum likelihood tree, partially disagreeing with previous phylogenetic studies (Aspöeck et al. Citation2012; Zhao et al. Citation2016; Yi et al. Citation2018; ).

Figure 1. Neighbor-joining (bootstrap repeat: 10,000), minimum evolution (bootstrap repeat: 10,000), and maximum likelihood (bootstrap repeat: 1,000) phylogenetic trees of seventeen species in Neuroptera including four available brown lacewings in family Hemerobiidae: Micromus angulatus (MK472073 in this study) and Micromus sp. YW-2016 (KT425075) in Microminae, Drepanepteryx phalaenoides (KT425087) and Neuronema laminatum (NC_028153) in Drepanepteryginae, as well as representatives of six other Neuropteran families: Ditaxis biseriate (Mantispidae, NC_013257), Rapisma xizangense (Polystoechotidae, NC_023362), Rapisma xizangense (Polystoechotidae, NC_023363), Polystoechotes punctatus (Polystoechotidae, NC_011278), Apochrysa matsumurae (Chrysopidae, NC_015095), Chrysopa pallens (Chrysopidae, NC_019618), Chrysoperla nipponensis (Chrysopidae, NC_015093), Ascaloptynx appendiculatus (Ascalaphidae, NC_011277), Libelloides macaronius (Ascalaphidae, NC_011277), Ascalohybris subjacens (Ascalaphidae, NC_021428), Thyridosmylus langii (Osmylidae, NC_021415), Neochaullodes bowringi (Corydaliae, NC_023444), a dobsonfly Corydalus cornutus (Corydaliae, NC_011276) as an outgroup species. Grey lines in the right-side display families and grey dotted lines present subfamilies. The numbers above/below branches indicate bootstrap support values of neighbor-joining, minimum evolution, and maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees, respectively.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aspöeck U, Haring E, Aspoeck H. 2012. The phylogeny of the Neuropterida: long lasting and current controversies and challenges (Insecta: Endopterygota). Arthropod Syst Phyl. 70:119–129.

- Beckenbach AT, Stewart JB. 2009. Insect mitochondrial genomics 3: the complete mitochondrial genome sequences of representatives from two neuropteroid orders: a dobsonfly (order Megaloptera) and a giant lacewing and an owlfly (order Neuroptera). Genome. 52:31–38.

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 30:2114–2120.

- Garzón-Orduña IJ, Menchaca-Armenta I, Contreras-Ramos A, Liu X, Winterton SL. 2016. The phylogeny of brown lacewings (Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae) reveals multiple reductions in wing venation. BMC Evol Biol. 16:192.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30:772–780.

- Kim J-H, Cho J-R, Lee M-S, Kang E-J, Byeon Y-W, Kim H-Y, Choi M-Y. 2013. Effect of Temperature on the Biological Attributes of the Brown Lacewing Micromus angulatus (Stephens)(Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae). Korean J Appl Entomol. 52:283–289.

- Kim T-H, Oh S-H, Kim Y-H, Jeong J-C. 2010. A new record of Micromus angulatus (Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae) from Korea. Anim Syst Evol Diversity. 26:157–159.

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35:1547–1549.

- Laslett D, Canbäck B. 2008. ARWEN: a program to detect tRNA genes in metazoan mitochondrial nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 24:172–175.

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv Preprint arXiv. 13033997.

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25:2078–2079.

- Navi S, Lingappa S, Patil R. 2010. Biology and feeding potential of Micromus timidus Hagen on cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii (Glover). Karnataka J Agric Sci. 23:652–654.

- New T. 1975. The biology of Chrysopidae and Hemerobiidae (Neuroptera), with reference to their usage as biocontrol agents: a review. Trans R Entomol Soc London. 127:115–140.

- Oswald JD. 1993. Revision and cladistic analysis of the world genera of the family Hemerobiidae (Insecta: Neuroptera). J NY Entomol Soc. 101:143–299.

- Samson P, Blood P. 1980. Voracity and searching ability of Chrysopa signata (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), Micromus tasmaniae (Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae), and Tropiconabis capsiformis (Hemiptera: Nabidae). Aust J Zool. 28:575–580.

- Sato T, Takada H. 2004. Biological studies on three Micromus species in Japan (Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae) to evaluate their potential as biological control agents against aphids: 1. Thermal effects on development and reproduction. Appl Entomol Zool. 39:417–425.

- Song N, Lin A, Zhao X. 2018. Insight into higher-level phylogeny of Neuropterida: evidence from secondary structures of mitochondrial rRNA genes and mitogenomic data. PloS One. 13:e0191826.

- Yi P, Yu P, Liu J, Xu H, Liu X. 2018. A DNA barcode reference library of Neuroptera (Insecta, Neuropterida) from Beijing. ZK. 807:127.

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18:821–829.

- Zhao QY, Wang Y, Kong YM. 2011. Optimizing de novo transcriptome assembly from short-read RNA-Seq data: a comparative study. BMC Bioinform. 12:S2.

- Zhao Y, Chen Y, Zhao J, Liu Z. 2016. First complete mitochondrial genome from the brown lacewings (Neuroptera: Hemerobiidae). Mitochondrial DNA A. 27:2763–2764.