Abstract

The complete chloroplast genome of Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb. isolated in Korea is 155,125 bp long (GC ratio is 36.9%) and has four subregions: 84,458 bp of large single copy (34.9%) and 18,737 bp of small single copy (30.4%) regions are separated by 25,965 bp of inverted repeat (42.6%) regions including 129 genes (84 protein-coding genes, eight rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs). 258 SNPs and 542 INDELs were identified as intraspecific variations against the partial genome (KY419942). Phylogenetic trees show that our chloroplast genome was clustered with the previous A. pilosa chloroplast genome.

Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb., which is a perennial herb in tribe Sanguisorbeae of Rosaceae, is primarily distributed over the Korean peninsula, Japan, China, Siberia, and Eastern Europe (Chung and Kim Citation2000; Seo et al. Citation2017). There are neighbor species in Korea, such as A. coreana and A. nipponica, considered as a variety of A. pilosa for a while (Chung and Kim Citation2000). Its root and aerial parts have been used as Traditional Chinese Medicines for hemostatic, antimalarial, and anti-dysenteric treatments (Park et al. Citation2004). Its partial chloroplast genome was uncovered from the individual which might be isolated in China (KY419942; Zhang et al. Citation2017) and its complete chloroplast genome was also published (Liu et al. Citation2020) but the sequence is not available as of May 2020.

Total DNA of A. pilosa isolated from Mt. Kwangdeok, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea, was extracted from fresh leaves using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The voucher was deposited in InfoBoss Cyber Herbarium (IN; Heo K-I, IB-01030; 38°06′21.7″N, 127°26′37.6″E). Genome was sequenced using HiSeqX at Macrogen Inc., Korea, and de novo assembly and confirmation were performed using Velvet 1.2.10 (Zerbino and Birney Citation2008), SOAPGapCloser 1.12 (Zhao et al. Citation2011), BWA 0.7.17 (Li Citation2013), and SAMtools 1.9 (Li et al. Citation2009). Geneious R11 11.0.5 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) was used for annotation based on A. pilosa chloroplast (KY419942).

Chloroplast genome of A. pilosa (GenBank accession is MT415946) is 155,125 bp (GC ratio is 36.9%) and has four subregions: 84,458 bp of large single copy (LSC; 34.9%) and 18,737 bp of small single copy (SSC; 30.4%) regions are separated by 25,695 bp of inverted repeat (IR; 42.6%). It contains 129 genes (84 protein-coding genes, eight rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs); 17 genes (seven protein-coding gene, four rRNAs, and six tRNAs) are duplicated in IR regions.

Due to lack of available complete chloroplast genome, partial chloroplast was used for identifying intraspecific variations: 258 SNPs and 542 INDELs were identified from aligned LSC, SSC, and IRb regions. Number of intraspecific variations is relatively large: several plant species, such as Goodyera schlechtendaliana (Oh et al. Citation2019a, Citation2019b), Gastrodia elata (Kang et al. Citation2020; Park, Suh, et al. Citation2020), Pyrus ussuriensis (Cho et al. Citation2019), Camellia japonica (Park, Kim, et al. Citation2019), Selaginella tamariscina (Park, Kim, et al. Citation2020), Marchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis (Kwon et al. Citation2019), displayed larger number of variations.

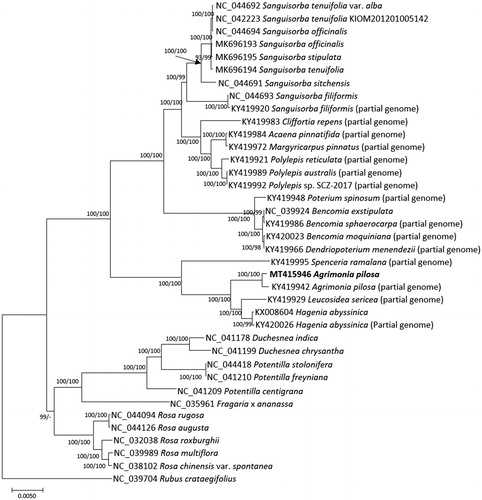

Thirty-eight chloroplast genomes including two A. pilosa chloroplasts were used for constructing bootstrapped maximum-likelihood neighbor-joining trees using MEGA X (Kumar et al. Citation2018) after aligning whole chloroplast genomes using MAFFT 7.450 (Katoh and Standley Citation2013) with adjusting three chloroplast genomes. Phylogenetic trees show that our chloroplast genome was clustered with the previous partial genome (Zhang et al. Citation2017; ). In addition, the topology of the trees agrees with the previous study (Zhang et al. Citation2017; ). Our chloroplast genome can be utilized to understand phylogenetic relationship of neighbor Agrimonia species in Korea, A. coreana and A. nipponica, after their complete chloroplast genomes are available.

Figure 1. Neighbor joining (bootstrap repeat is 10,000) and maximum-likelihood (bootstrap repeat is 1,000) phylogenetic trees of ten Rosa chloroplast genomes and three outgroup species: Agrimonia pilosa (MT415946 in this study and KY419942; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Acaena pinnatifida (KY419984; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Bencomia exstipulata (NC_039924), Bencomia moquiniana (KY420023; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Bencomia sphaerocarpa (KY419986; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Cliffortia repens (KY419983; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Dendriopoterium menendezii (KY419966; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Fragaria x ananassa cultivar Benihoppe (NC_035961; Cheng et al. Citation2017), Hagenia abyssinica (KX008604; Gichira et al. Citation2017) and KY420026; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Leucosidea sericea (KY419929; partial genome (Zhang et al. Citation2017)), Margyricarpus pinnatus (KY419972; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Polylepis australis (KY419989; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Polylepis reticulata (KY419921; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Polylepis sp. SCZ-2017 (KY419992; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Potentilla centigrana (NC_041209; Park et al. Citation2019a), Potentilla freyniana (NC_041210; Park et al. Citation2019b), Duchesnea chrysantha (NC_041199; Park, Heo, et al. Citation2019), Duchesnea indica (NC_041178; Heo, Kim, et al. Citation2019), Potentilla stolonifera var. quelpaertensis (NC_044418; Heo, Park, et al. Citation2019), Poterium spinosum (KY419948; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Rosa chinensis var. spontanea (NC_038102; Jian et al. Citation2018), Rosa multiflora (NC_039989; Jeon and Kim Citation2019), Rosa roxburghii (NC_032038; Wang et al. Citation2018), Rosa rugosa (NC_044094; Kim et al. Citation2019), Rosa angusta (NC_044126; Kim et al. Citation2019), Rubus crataegifolius (NC_039704; Yang et al. Citation2017), Sanguisorba filiformis (NC_044693 (Meng et al. Citation2018) and KY419920; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Sanguisorba officinalis (NC_044694 (Meng et al. Citation2018) and MK696193), Sanguisorba sitchensis (NC_044691; Meng et al. Citation2018), Sanguisorba tenuifolia var. alba (NC_044692; Meng et al. Citation2018), Sanguisorba tenuifolia (NC_042223 (Park et al. Citation2018) and MK696195), Spenceria ramalana (KY419995; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017), Sanguisorba stipulate (MK696195; partial genome; Zhang et al. Citation2017). Phylogenetic tree was drawn based on maximum-likelihood tree. The numbers above branches indicate bootstrap support values of maximum-likelihood and neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree, respectively.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement

Chloroplast genome sequence can be accessed via accession number MT415946 in NCBI GenBank.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cheng H, Li J, Zhang H, Cai B, Gao Z, Qiao Y, Mi L. 2017. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) and comparison with related species of Rosaceae. PeerJ. 5:e3919

- Cho M-S, Kim Y, Kim S-C, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Korean Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim. (Rosaceae): providing genetic background of two types of P. ussuriensis. Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(2):2424–2425.

- Chung KS, Kim YS. 2000. A taxonomic study on the genus Agrimonia (Rosaceae) in Korea. Korean J Pl Taxon. 30(4):315–337.

- Gichira AW, Li Z, Saina JK, Long Z, Hu G, Gituru RW, Wang Q, Chen J. 2017. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of an endemic monotypic genus Hagenia (Rosaceae): structural comparative analysis, gene content and microsatellite detection. PeerJ. 5:e2846

- Heo K-I, Kim Y, Maki M, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of mock strawberry, Duchesnea indica (Andrews) Th. Wolf (Rosoideae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(1):560–562.

- Heo K-I, Park J, Kim Y, Kwon W. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Potentilla stolonifera var. quelpaertensis Nakai. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1289–1291.

- Jeon J-H, Kim S-C. 2019. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome sequences of three closely related East-Asian wild roses (Rosa sect. Synstylae; Rosaceae). Genes. 10(1):23.

- Jian H-Y, Zhang Y-H, Yan H-J, Qiu X-Q, Wang Q-G, Li S-B, Zhang S-D. 2018. The complete chloroplast genome of a key ancestor of modern roses, Rosa chinensis var. spontanea, and a comparison with congeneric species. Molecules. 23(2):389.

- Kang M-J, Kim S-C, Lee H-R, Lee S-A, Lee J-W, Kim T-D, Park E-J. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome of Korean Gastrodia elata Blume. Mitochondrial DNA B. 5(1):1015–1016.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30(4):772–780.

- Kim Y, Heo K-I, Nam S, Xi H, Lee S, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of candidate new species from Rosa rugosa in Korea (Rosaceae.). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(2):2433–2435.

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35(6):1547–1549.

- Kwon W, Kim Y, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Korean Marchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis Bischl. & Boisselier: low genetic diversity between Korea and Japan. Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(1):959–960.

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv Preprint arXiv. 13033997.

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25(16):2078–2079.

- Liu T, Qian J, Du Z, Wang J, Duan B. 2020. Complete genome and phylogenetic analysis of Agrimonia pilosa Ldb. Mitochondrial DNA B. 5(2):1435–1436.

- Meng X-X, Xian Y-F, Xiang L, Zhang D, Shi Y-H, Wu M-L, Dong G-Q, Ip S-P, Lin Z-X, Wu L, et al. 2018. Complete chloroplast genomes from Sanguisorba: identity and variation among four species. Molecules. 23(9):2137.

- Oh S-H, Suh HJ, Park J, Kim Y, Kim S. 2019a. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of a morphotype of Goodyera schlechtendaliana (Orchidaceae) with the column appendages. Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(1):626–627.

- Oh S-H, Suh HJ, Park J, Kim Y, Kim S. 2019b. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Goodyera schlechtendaliana in Korea (Orchidaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(2):2692–2693.

- Park E-J, Oh H, Kang T-H, Sohn D-H, Kim Y-C. 2004. An isocoumarin with hepatoprotective activity in Hep G2 and primary hepatocytes from Agrimonia pilosa. Arch Pharm Res. 27(9):944–946.

- Park I, Yang S, Kim WJ, Noh P, Lee HO, Moon BC. 2018. Complete chloroplast genome of Sanguisorba × tenuifolia Fisch. ex Link. Mitochondrial DNA B. 3(2):909–910.

- Park J, Heo K-I, Kim Y, Kwon W. 2019a. The complete chloroplast genome of Potentilla centigrana Maxim. (Rosaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(1):688–689.

- Park J, Heo K-I, Kim Y, Kwon W. 2019b. The complete chloroplast genome of Potentilla freyniana Bornm. (Rosaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(2):2420–2421.

- Park J, Heo K-I, Kim Y, Maki M, Lee S. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome, Duchesnea chrysantha (Zoll. & Moritzi) Miq. (Rosoideae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(1):951–952.

- Park J, Kim Y, Lee G-H, Park C-H. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome of Selaginella tamariscina (Beauv.) Spring (Selaginellaceae) isolated in Korea. Mitochondrial DNA B. 5(2):1654–1656.

- Park J, Kim Y, Xi H, Oh YJ, Hahm KM, Ko J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of common camellia tree, Camellia japonica L. (Theaceae), adapted to cold environment in Korea. Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(1):1038–1040.

- Park J, Suh Y, Kim S. 2020. A complete chloroplast genome sequence of Gastrodia elata (Orchidaceae) represents high sequence variation in the species. Mitochondrial DNA B. 5(1):517–519.

- Seo UM, Nguyen DH, Zhao BT, Min BS, Woo MH. 2017. Flavanonol glucosides from the aerial parts of Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb. and their acetylcholinesterase inhibitory effects. Carbohydr Res. 445:75–79.

- Wang Q, Hu H, An J, Bai G, Ren Q, Liu J. 2018. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Rosa roxburghii and its phylogenetic analysis. Mitochondrial DNA B. 3(1):149–150.

- Yang JY, Pak J-H, Kim S-C. 2017. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Korean raspberry Rubus crataegifolius (Rosaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 2(2):793–794.

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18(5):821–829.

- Zhang SD, Jin JJ, Chen SY, Chase MW, Soltis DE, Li HT, Yang JB, Li DZ, Yi TS. 2017. Diversification of Rosaceae since the Late Cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics. New Phytol. 214(3):1355–1367.

- Zhao Q-Y, Wang Y, Kong Y-M, Luo D, Li X, Hao P. 2011. Optimizing de novo transcriptome assembly from short-read RNA-Seq data: a comparative study. BMC Bioinf. 12(Suppl 14):S2.