Abstract

The complete mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) of Amorophaga japonica Robinson, 1986 (Lepidoptera: Tineidae), comprises 15,027 base pairs (bp) and contains a typical set of genes (13 protein-coding genes [PCGs], 2 rRNA genes, and 22 tRNA genes), and 1 non-coding region. The genome has an arrangement, trnW-trnY-trnC, instead of typical trnW- trnC-trnY at the ND2 and COI junction. This arrangement is unique in lepidopteran mitogenomes. Unlike most lepidopteran insects, which have CGA as the start codon for the COI gene sequence, A. japonica COI had a typical ATT codon. The A + T-rich region was unusually short, with only 199 bp. Phylogenetic analyses with concatenated sequences of the 13 PCGs and two rRNA genes using the Bayesian inference method placed A. japonica in Tineidae as a sister to the cofamilial species, Tineola bisselliella, with high nodal support (Bayesian posterior probability [BPP] = 0.99), presenting the superfamily Tineoidea in a monophyletic group with a BPP of 0.99. Gracillarioidea, represented by three species of Gracillariidae, formed a monophyletic group with the highest BPP, but the Leucoptera malifoliella in Yponomeutoidea was unusually grouped together with the Gracillarioidea with the highest nodal support. As more mitogenome sequences are available, further analysis to infer the relationships among superfamilies of Lepidoptera might be possible.

Four species of Amorophaga are recognized globally, and A. japonica is distributed throughout China, Korea, and Japan (Zagulajev Citation1975; Robinson Citation1986). This species feeds on fruit bodies of the wood-decaying bracket fungus Cryptoporus volvatus (Polyporaceae: Basidiomycota) in Japan (Kadowaki and Yamazoe Citation2011). The larvae of the species pupate in interstices of fruit bodies (Osada et al. Citation2015).

An adult male A. japonica was collected from Naechon-myeon, Pocheon City, Gyeonggido Province, South Korea (37°48′37.0ʺN, 127°15′21.7ʺE) in 2013. This voucher specimen was deposited at the Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea, under Accession No. CNU7296. Using DNA extracted from the hind legs, three long overlapping fragments (LFs; COI-ND4, ND5-lrRNA, and lrRNA-COI) were amplified using previously described primers (Kim et al. Citation2012). These three LFs were used as templates to amplify 26 short fragments (Kim et al. Citation2012).

Phylogenetic analysis using the concatenated nucleotide sequences of 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs) and two rRNA genes was performed using the Bayesian inference (BI) method implemented in CIPRES Portal v. 3.1 (Miller et al. Citation2010). An optimal partitioning scheme (six partitions) and substitution model (GTR + Gamma + I) were determined using PartitionFinder 2 and the greedy algorithm (Lanfear et al. Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2016).

The complete 15,027-base pair (bp) mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) of A. japonica was composed of typical gene sets (2 rRNAs, 22 tRNAs, and 13 PCGs) and a major non-coding A + T-rich region (GenBank accession no. MH823253). The length of the A. japonica A + T-rich region was the second shortest (199 bp), next to Eumeta variegata (94 bp; Jeong et al. Citation2018), among sequenced Tineoidea, Gracillarioidea, and Yponomeutoidea (94–1610 bp; data not shown). The genome has an arrangement trnW-trnY-trnC, instead of typical trnW-trnC-trnY at the ND2 and COI junction, presenting a new gene arrangement in lepidopteran mitogenomes (Park et al. Citation2016). All PCGs contained the typical ATN start codon, including COI (four ATT, three ATA, and six ATG). This differs from the start codon for COI in other available species of Tineoidea, Gracillarioidea, and Yponomeutoidea (data not shown), as well as most species of Lepidoptera (Kim et al. Citation2010). The A/T content of the whole mitogenome was 81.6%; however, it varied among the genes as follows: A + T-rich region, 95.5%; srRNA, 86.9%; lrRNA, 86.5%; tRNAs, 83.2%; and PCGs, 80.1%.

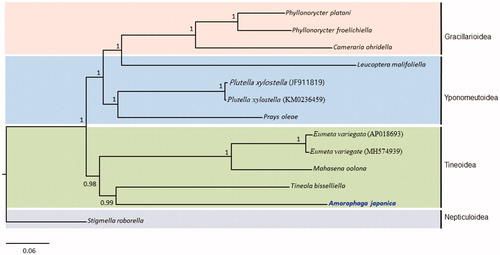

Phylogenetic analyses performed using the concatenated sequences of the 13 PCGs and 2 rRNA genes using the BI method placed A. japonica in Tineidae as the sister to a cofamilial species, Tineola bisselliella, with high nodal support (Bayesian posterior probability [BPP] = 0.99) (). It also placed E. variegata and Mahasena oolona, which belong to the family Psychidae as sister species to each other, presenting Tineoidea as a monophyletic group with high nodal support (BPP = 0.98). Gracillarioidea, which was represented by three species of Gracillariidae formed a monophyletic group with the highest BPP, but Leucoptera malifoliella, belonging to the family Lyonetiidae in Yponomeutoidea, was unusually grouped together with Gracillarioidea with the highest nodal support (BPP = 1). Currently, only limited mitogenome sequences are available from Gracillarioidea, Tineoidea, and Yponomeutoidea. Therefore, atypical relationships are unavoidable. Nevertheless, a previous large-scale phylogenetic analyses using 14,658 characters from 19 nuclear PCGs for lepidopteran phylogeny instead has shown a closer relationship of the genus Leucoptera in Lyonetiidae to Yponomeutoidea (Regier et al. Citation2013). Therefore, an additional, scrutinized analysis with extended taxon sampling is essential to verify current unexpected relationships.

Figure 1. Bayesian inference (BI) method-based phylogenetic tree for three superfamilies in Ditrysia (Tineoidea, Gracillarioidea, and Yponomeutoidea) obtained using concatenated sequences of 13 PCGs and 2 rRNAs. The numbers at each node indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPPs). The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. One species of Nepticuloidea (Stigmella roborella) was included as an outgroup. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Tineola bisselliella, KJ508045 (Timmermans et al. Citation2014); Mahasena oolona, KY856825 (Li et al. Citation2017); Eumeta variegate, AP018693 and MH574939 (Arakawa et al. Citation2018; Jeong et al. Citation2018); Phyllonorycter froelichiella, KJ508048 (Timmermans et al. Citation2014); Phyllonorycter platani, KJ508044 (Timmermans et al. Citation2014); Cameraria ohridella, KJ508042 (Timmermans et al. Citation2014); Plutella xylostella, JF911819 and KM023645 (Wei et al. Citation2013; Dai et al. Citation2016); Leucoptera malifoliella, JN790955 (Wu et al. Citation2012); Prays oleae, KM874804 (van Asch et al. Citation2014); and Stigmella roborella, KJ508054 (Timmermans et al. Citation2014).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Mendeley Data at http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/yhmx6hpysr.1.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arakawa K, Kono N, Ohtoshi R, Hiroyuki N, Tomita M. 2018. The complete mitochondrial genome of Eumeta variegata (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 3(2):812–813.

- Jeong JS, Kim MJ, Kim SS, Kim I. 2018. Complete mitochondrial genome of the female-wingless bagworm moth, Eumeta variegata Snellen, 1879 (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 3(2):1037–1039.

- Kadowaki K, Yamazoe K. 2011. Geographic patterns of insect communities on the wood-decaying bracket fungus Cryptorus volvatus Polyporaceae: Basidiomycota. Japan J Entomol. 14:93–104. (Japanese).

- Dai LS, Zhu BJ, Qian C, Zhang CF, Li J, Wang L, Wei GQ, Liu CL. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(2):1512–1513.

- Kim JS, Park JS, Kim MJ, Kang PD, Kim SG, Jin BR, Han YS, Kim I. 2012. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the mitochondrial genome of eri-silkworm, Samia cynthia ricini (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). J Asia Pac Entomol. 15(1):162–173.

- Kim MJ, Wan X, Kim KG, Hwang JS, Kim I. 2010. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the mitogenome of endangered Eumenis autonoe (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Afr J Biotechnol. 9:735–754.

- Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SY, Guindon S. 2012. PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 29(6):1695–1701.

- Lanfear R, Calcott B, Kainer D, Mayer C, Stamatakis A. 2014. Selecting optimal partitioning schemes for phylogenomic datasets. BMC Evol Biol. 14:82.

- Lanfear R, Frandsen PB, Wright AM, Senfeld T, Calcott B. 2016. PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol E. 34:772–773.

- Li PW, Chen SC, Xu YM, Wang XQ, Hu X, Peng P. 2017. The complete mitochondrial genome of a tea bagworm, Mahasena colona (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2(2):381–382.

- Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. 2010. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. Proceedings of the 9th Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), IEEE, 14 November 2010, New Orleans, LA; p. 1–8.

- Osada Y, Sakai M, Hirowatari T. 2015. Morphology of adult and immature stages of Amorqphaga Japonica Robinson, 1986 (Lepidoptera, Tineidae). Lepidoptera Sci. 66:120–128.

- Park JS, Kim MJ, Jeong SY, Kim SS, Kim I. 2016. Complete mitochondrial genomes of two gelechioids, Mesophleps albilinella and Dichomeris ustalella (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), with a description of gene rearrangement in Lepidoptera. Curr Genet. 62(4):809–826.

- Regier JC, Mitter C, Zwick A, Bazinet AL, Cummings MP, Kawahara AY, Sohn J-C, Zwickl DJ, Cho S, Davis DR, et al. 2013. A large-scale, higher-level, molecular phylogenetic study of the insect order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies). PLOS One. 8(3):e58568

- Robinson GS. 1986. Fungus moths: a review of the Scardiinae (Lepidoptera: Tineidae). Bull Br Mus Nat Hist. 52:37–181.

- Timmermans MJ, Lees DC, Simonsen TJ. 2014. Towards a mitogenomic phylogeny of Lepidoptera. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 79:169–178.

- van Asch B, Blibech I, Pereira-Castro I, Rei FT, da Costa LT. 2014. The mitochondrial genome of Prays oleae (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Praydidae). Mitochondria DNA. 27:1–2.

- Wei SJ, Shi BC, Gong YJ, Li Q, Chen XX. 2013. Characterization of the mitochondrial genome of the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) and phylogenetic analysis of advanced moths and butterflies. DNA Cell Biol. 32(4):173–187.

- Wu YP, Zhao JL, Su TJ, Li J, Yu F, Chesters D, Fan RJ, Chen MC, Wu CS, Zhu CD. 2012. The complete mitochondrial genome of Leucoptera malifoliella Costa (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae). DNA Cell Biol. 31(10):1508–1522.

- Zagulajev AK. 1975. Tineidae; part 5 – subfamily Myrmecozelinae. Fauna SSSR. 108:1–426.