Abstract

We completed chloroplast genome of Wiesnerella denudata (Mitt.) Steph, only one species of the monotypic Wiesnerella genus and family Wiesnerellaceae Inoue. It is 122,500 bp and has four subregions: 82,143 bp of large single copy (LSC) and 20,009 bp of small single copy (SSC) regions are separated by 10,174 bp of inverted repeat (IR) regions including 132 genes (88 protein-coding genes, eight rRNAs, and 36 tRNAs). The overall GC content is 28.8% and those in the LSC, SSC, and IR regions are 26.4, 24.6, and 42.8%, respectively. Phylogenetic trees show incongruencies of phylogenetic relationship of W. denudata, requiring additional research.

Genus Wienerella Schiffn. is a monotypic genus of thalloid liverworts covering only one accepted species (Borovichev and Bakalin Citation2014). Wiesnerella denudata Steph., the temperate to subtropical Himalaya-East Asian species, is distributed in Indonesia, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Southern China, Japan, Russian Far East, and Korea (Borovichev and Bakalin Citation2014). Wiesnerella denudata grows on moist to wet thin soil in humus or rocks, commonly mixture of Dumortiera hirsute (Sw.) Nees and Conocephalum salebrosum Szweyk., Buczk. & Odrzyk., and is characterized by thin thallus with simple air pore, ventral scales in two rows with single appendage, and bivalved involucres (Inoue Citation1976; Crandall-Stotler et al. Citation2009). We completed chloroplast genome sequences of W. denudata for understanding its phylogenetic position.

The plants of W. denudata collected in Jeju city, Korea (Voucher in Jeonbuk National University Herbarium (JNU), Korea; S.S. Choi, CS-201126; 33.48318 N, 126.73896 E) was used for extracting DNA with DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Genome sequencing was performed using NovaSeq6000 at Macrogen Inc., Seoul, Korea. Chloroplast genome was completed by Velvet 1.2.10 (Zerbino and Birney Citation2008), SOAPGapCloser 1.12 (Zhao et al. Citation2011), BWA 0.7.17 (Li Citation2013), and SAMtools 1.9 (Li et al. Citation2009) under the environment of Genome Information System (GeIS; http://geis.infoboss.co.kr/). Geneious R11 11.0.5 (Biomatters Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) was used for annotation based on Marchantia polymorpha chloroplast genome (NC_037057; Bowman et al. Citation2017).

The chloroplast genome of W. denudata (GenBank accession is MT712073) is 122,500 bp long (GC ratio is 28.8%) and has four subregions: 82,143 bp of large single copy (LSC; 26.4%) and 20,009 bp of small single copy (SSC; 24.6%) regions are separated by 10,174 bp of inverted repeat (IR; 42.8%). It contains 132 genes (88 protein-coding genes, eight rRNAs, and 36 tRNAs); nine genes (four rRNAs and five tRNAs) are duplicated in IR regions. Gene order of W. denudata chloroplast is identical to those in Marchantiales without considering gene loss or gain along with seven species.

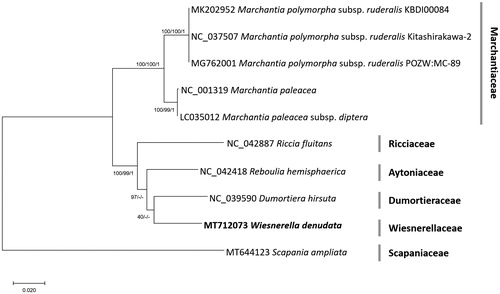

Ten complete chloroplast genomes including W. denudata were used for constructing neighbor joining (NJ; bootstrap repeat is 10,000), maximum likelihood (ML; bootstrap repeat is 1,000), and Bayesian Inference phylogenic trees (BI; number of generations is 1,100,000) using MEGA X (Kumar et al. Citation2018) and Mr. Bayes 3.2.7a (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist Citation2001), respectively, after aligning whole chloroplast genome sequences using MAFFT version 7.450 (Katoh and Standley Citation2013). Phylogenetic trees show that W. denudata is clustered with Dumortiera hirsuta only in ML tree with low supportive value, while W. denudata is clustered with Reboulia hemisphaerica in both NJ and BI trees with high supportive value (). It is interesting result because W. denudata is only one species in the family Wiesnerellaceae with clear distinct morphological features. In addition, Crandall-Stotler et al. reported that chloroplast gene of W. denudata was aligned with those of Riccaceae (Crandall-Stotler et al. Citation2009), displaying incongruent with the phylogenetic trees (). This incongruencies was not reported from those mitochondrial genome analyses (Kwon et al. Citation2019c, Citation2019d; Min et al. Citation2020). Taken together, additional studies for understanding these incongruencies are strongly required in near future.

Figure 1. Neighbor joining (bootstrap repeat is 10,000), maximum likelihood (bootstrap repeat is 1000), and Bayesian inference phylogenetic (number of generation is 1,100,000) trees of 10 complete chloroplast genomes: Wiesnerella denudata (MT712073 in this study), Dumortiera hirsuta (NC_039590; Kwon et al. Citation2019b), Marchantia paleacea (NC_001319; Shimda and Sugiuro Citation1991), Marchantia paleacea subsp. Diptera (LC035012), Marchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis (NC_037507, MK202952, and MG762001; Kijak et al. Citation2016; Bowman et al. Citation2017; Kwon et al. Citation2019a), Reboulia hemisphaerica (NC_042418; Kwon, Min, Kim, et al. Citation2019), Riccia fluitans (NC_042887; Kwon, Min, Xi, et al. Citation2019), and Scapania ampliata (MT644123; doi:10,1080/23802359.2020.1791011) as outgroup species. Phylogenetic tree was drawn based on the maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree. Family names were displayed with gray bars in the phylogenetic tree. The numbers above branches indicate bootstrap support values of maximum likelihood, neighbor joining, and Bayesian Inference phylogenetic trees, respectively.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Chloroplast genome sequence can be accessed via accession number MT712073 in NCBI GenBank.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Borovichev EA, Bakalin VA. 2014. A survey of Marchantiales in the Russian far east II. Wiesnerllaceae – a new family for the Russian liverworts flora. Arct J Bryol. 23(1):1–4.

- Bowman JL, Kohchi T, Yamato KT, Jenkins J, Shu S, Ishizaki K, Yamaoka S, Nishihama R, Nakamura Y, Berger F, et al. 2017. Insights into land plant evolution garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha genome. Cell. 171(2):287–304.

- Crandall-Stotler B, Stotler R, Long D. 2009. Phylogeny and classification of the Marchantiophyta. Edinburgh J Bot. 66(1):155–198.

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. 2001. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 17(8):754–755.

- Inoue H. 1976. Illustrations of Japanese Hepaticae. Tokyo, Japan: Tsukijishokan. p. 1–193.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30(4):772–780.

- Kijak H, Rurek M, Nowak W, Dabert M, Odrzykoski IJ, Berger F, Dolan L. 2016. Resequencing the ‘classic’ Marchantia polymorpha chloroplast genome. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308699734_Resequencing_the_%27classic%27_Marchantia_polymorpha_chloroplast_genome

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35(6):1547–1549.

- Kwon W, Kim Y, Park J. 2019a. The complete chloroplast genome of Korean Marchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis Bischl. & Boisselier: low genetic diversity between Korea and Japan. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):959–960.

- Kwon W, Kim Y, Park J. 2019b. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Dumortiera hirsuta (Sw.) Nees (Marchantiophyta, Dumortieraceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):318–319.

- Kwon W, Kim Y, Park J. 2019c. The complete mitochondrial genome of Dumortiera hirsuta (Sw.) Nees (Dumortieraceae, Marchantiophyta). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1586–1587.

- Kwon W, Kim Y, Park J. 2019d. The complete mitochondrial genome of Korean Marchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis Bischl. & Boisselier: inverted repeats on mitochondrial genome between Korean and Japanese isolates. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):769–770.

- Kwon W, Min J, Kim Y, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Reboulia hemisphaerica (L.) Raddi (Aytoniaceae, Marchantiophyta). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1459–1460.

- Kwon W, Min J, Xi H, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Riccia fluitans L. (Ricciaceae, Marchantiophyta). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1895–1896.

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv Preprint arXiv:13033997.

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25(16):2078–2079.

- Min J, Kwon W, Xi H, Park J. 2020. The complete mitochondrial genome of Riccia fluitans L. (Ricciaceae, Marchantiophyta): investigation of intraspecific variations on mitochondrial genomes of R. fluitans. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 5(2):1220–1222.

- Shimda H, Sugiuro M. 1991. Fine structural features of the chloroplast genome: comparison of the sequenced chloroplast genomes. Nucl Acids Res. 19(5):983–995.

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18(5):821–829.

- Zhao QY, Wang Y, Kong YM, Luo D, Li X, Hao P. 2011. Optimizing de novo transcriptome assembly from short-read RNA-Seq data: a comparative study. BMC Bioinf. 12(14):S2.