Abstract

Sedum bulbiferum is a traditional medicinal plant in China, with few reports on its chloroplast genome. In this study, the chloroplast genome of Sedum bulbiferum was characterized, and its phylogenetic position among other closely related species was studied. The results showed that the full length of the chloroplast genome was 150,074 bp, containing a large single-copy (LSC) region and a small single-copy (SSC) region of 81,730 and 16,726 bp, respectively, as well as two inverted repeat regions (IRs) of 25,809 bp like other plants. A total of 128 genes were found, including 83 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes, and eight rRNA genes. Phylogenetic analysis showed that Sedum bulbiferum is closely related to Sedum emarginatum, Sedum alfredii, Sedum tricarpum, Sedum plumbizincicola, and Sedum sarmentosum.

Introduction

Sedum bulbiferum Makino 1891 is a perennial herb of the genus Sedum in the Crassulaceae. It has a fibrous root, 7–22 cm long stems, white globular bulbils that are viviparous, and a 3-branched and numerous-flowered cyme. The plant is widely distributed in Hunan, Hubei, Guangdong, Guangxi, and other Chinese provinces. It has grown in the Korean peninsula and Japan, preferring the shade of low mountains and flat trees below 1000 meters above sea level () (Wu and Raven Citation2001). After drying, S. bulbiferum has medical properties in traditional Chinese medicine culture, commonly used in China. It has been reported that S. bulbiferum has various pharmacological activities, such as treating malaria, rheumatism, and indigestion. Previously, it was also found that flavonoids isolated from other Sedum plants have significant antitumor biological activities (Meng et al. Citation2019). Previous reports on S. bulbiferum have mainly focused on its pharmacology. However, there are few reports on its evolution and classification, and its chloroplast genome is unknown. Therefore, the chloroplast genome of S. bulbiferum is sequenced and described in this study, and a phylogenetic tree based on the chloroplast genome is constructed to explore its phylogenetic status. This provides a theoretical reference for further phylogenetic research and other related research.

Figure 1. The picture of the collected sample of S. bulbiferum. The picture is self-taken by Zijie Deng at Changde Baima Lake Cultural Park, Changde, Hunan province, China (29°03′6.55ʺN, 111°39′59.54ʺE; 33 m). In the picture, S. bulbiferum is the wide-spread plant with small leaves, which has a fibrous root, 7–22 cm long stems, white globular bulbils that are viviparous, and a 3-branched and numerous-flowered cyme.

Materials

For plant materials, five fresh leaves were obtained from S. bulbiferum cultivated in the Changde Baima Lake Cultural Park, Changde, Hunan province, China (29°03′6.55ʺN, 111°39′59.54ʺE; 33 m). Later, the voucher specimens were dried and preserved well at the College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Hunan University of Arts and Sciences (Contact Person: Kerui Huang, [email protected], voucher number ZYJT005).

Methods

Healthy leaves were selected and dried to extract total genomic DNA using the DNeasy plant tissue kit (TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing). Subsequently, the library was constructed, and the sequencing process was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (Shanghai Personalbio Technology Co., Ltd., China). After filtering out the low-quality reads using fastp (Chen et al. Citation2018), 67,498,968 reads were obtained. Then, the obtained reads were used for the de novo assembly of the S. bulbiferum chloroplast genome using GetOrganelle v1.7.5 (Jin et al. Citation2020) (Supplemental material 1). Finally, CPGAVAS2 (Shi et al. Citation2019) was used to annotate the chloroplast genome.

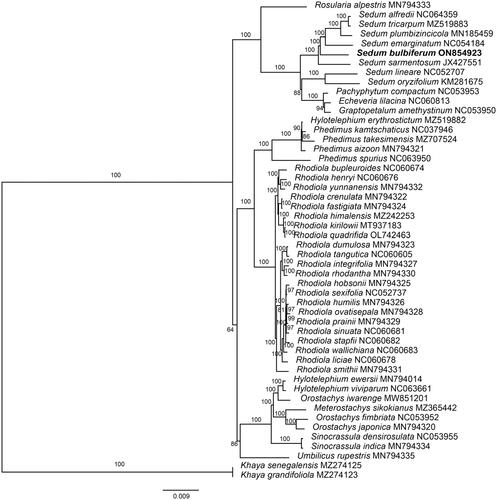

To determine the phylogenetic location of S. bulbiferum, a maximum-likelihood (ML) tree was constructed using IQ-Tree v1.6.8 (Chernomor et al. Citation2016) based on the chloroplast genome of S. bulbiferum and its related species. A total of 49 chloroplast genomes were obtained from GenBank. A total of 55 protein-coding genes shared by all genomes were found and extracted, then MAFFT v7.313 (Rozewicki et al. Citation2019) was used for separate alignment of each gene. Then, Gblocks 0.91 b was used for sequence masking of each gene, and end-to-end connections of the genes were used to form a supergene of each species (Guo et al. Citation2022). Maximum likelihood phylogenies were inferred using IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al. Citation2015) under the TVM + I + F model for 5000 ultrafast bootstraps and the Shimodaira–Hasegawa–like approximate likelihood-ratio test.

Results

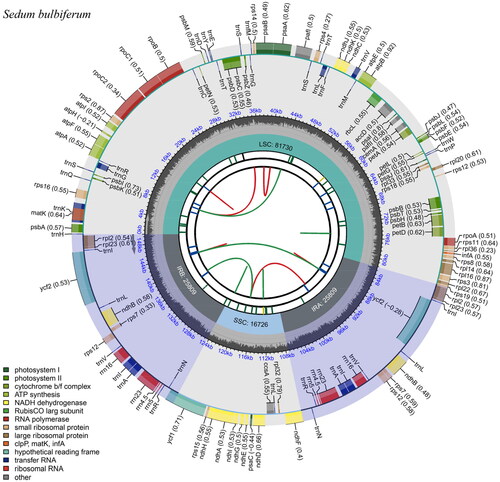

The chloroplast gene structure of Sedum bulbiferum ( and Supplemental material 2), as with most plants, is a circular molecule with a length of 150,074 bp that has a typical quadripartite structure comprising a large single-copy (LSC) region (81,730 bp in length), a small single-copy (SSC) region (16,726 bp in length), and two inverted repeat regions (IRs, 25,809 bp in length). The G + C content was 37.70% for the whole chloroplast and 42.88% for the IRs, which was higher than that of the LSC and SSC regions (35.61% and 31.90%, respectively). A total of 128 genes were found in the whole chloroplast genome, including 83 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes, and eight rRNA genes.

Figure 2. Gene map of the S. bulbiferum chloroplast genome. From the center outward, the first track indicates the dispersed repeats; The second track shows the long tandem repeats as short blue bars; The third track shows the short tandem repeats or microsatellite sequences as short bars with different colors; The fourth track shows small single-copy (SSC), inverted repeat (Ira and Irb), and large single-copy (LSC) regions. The GC content along the genome is plotted on the fifth track; The genes are shown on the sixth track.

The phylogenetic analysis () showed that S. emarginatum, S. alfredii, S. tricarpum, S. plumbizincicola, and S. sarmentosum were closely related to S. bulbiferum, which is generally consistent with previous studies (Messerschmid et al. Citation2020).

Figure 3. Maximum-likelihood (ML) tree of S. bulbiferum and 49 relative species was reconstructed using the IQ-Tree based on 55 protein-coding gene sequences shared by all genomes under the TVM + I + F model for 5000 ultrafast bootstraps, as well as the Shimodaira–Hasegawa–like approximate likelihood-ratio test. Bootstrap values are shown next to the nodes. The following sequences were used: Rosularia alpestris MN794333 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Sedum tricarpum MZ519883 (Chen et al., Citation2022), Sedum plumbizincicola MN185459 (Ding et al. Citation2019), Sedum lineare NC052707 (Tang et al. Citation2021), Sedum oryzifolium KM281675 (Li and Chen Citation2020), Echeveria lilacina NC060813 (Nah et al. Citation2022), Hylotelephium erythrostictum MZ519882 (Chen et al., Citation2022), Phedimus kamtschaticus NC037946 (Seo and Kim Citation2018), Phedimus takesimensis MZ707524 (Seo et al. Citation2020), Phedimus aizoon MN794321 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola bupleuroides NC060674 (Zhao et al. Citation2021), Rhodiola henryi NC060676 (Zhao et al. Citation2021), Rhodiola yunnanensis MN794332 (Zhao et al. Citation2021), Rhodiola crenulata MN794322 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola fastigiata MN794324 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola kirilowii MT937183 (Zhang and Liu Citation2021), Rhodiola quadrifida OL742463 (Zhao et al. Citation2022), Rhodiola dumulosa MN794323 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola tangutica NC060605 (Lakshmanan et al. Citation2011), Rhodiola integrifolia MN794327 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola rhodantha MN794330 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola hobsonii MN794325 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola humilis MN794326 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola ovatisepala MN794328 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola prainii MN794329 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Rhodiola sinuata NC060681 (Zhao et al. Citation2021), Rhodiola stapfii NC060682 (Zhao et al. Citation2021), Rhodiola wallichiana NC060683 (Zhao et al. Citation2021), Rhodiola liciae NC060678 (Zhao et al. Citation2021), Rhodiola smithii MN794331 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Hylotelephium ewersii MN794014 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Meterostachys sikokianus MZ365442 (Kang et al. Citation2022), Orostachys japonica MN794320 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Sinocrassula indica MN794334 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Umbilicus rupestris MN794335 (Zhao et al. Citation2020), Khaya grandifoliola MZ274123 (Mascarello et al. Citation2021), Khaya grandifoliola MZ274125 (Mascarello et al. Citation2021).

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, the whole chloroplast genome of S. bulbiferum was reported, and the phylogenic analysis results agreed with previous studies. However, due to the lack of the chloroplast genome of Sedum in public databases, the phylogeny of this genus requires further study. This study would provide a basis for the development of genetic resources and the evolutionary relationship of Sedum.

Author contributions

Kerui Huang and Yun Wang designed the study; Zijie Deng, Peng Xie, Suisui Xie, Ningyun Zhang, Hanbin Yin, and Ping Mo collected the samples and interpreted the data; Zijie Deng and Kerui Huang analyzed the data; Zijie Deng drafted the manuscript; Yun Wang and Kerui Huang revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics statement

Field studies complied with local legislation, and appropriate permissions were granted by Changde Baima Lake Cultural Park before the samples were collected.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (334.3 KB)Acknowledgement

We thank enago (www.enago.cn) for the help of English editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Sedum bulbiferum has been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number ON854923 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON854923). The associated BioProject, SRA, and Bio-Sample numbers are PRJNA867513, SRR20981864, and SAMN30203515, respectively.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chen J, Zhou H, Gong W. 2022. The complete chloroplast genome of Sedum tricarpum Makino.(Crassulaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7(1):15–16.

- Chen J, Zhou H, Gong W. 2022. The complete chloroplast genome of Hylotelephium erythrostictum (Miq.) H. Ohba (Crassulaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7(2):365–366.

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. 2018. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 34(17):i884–i890.

- Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2016. Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Syst Biol. 65(6):997–1008.

- Ding H, Zhu R, Dong J, Dong J, Bi D, Jiang L, Zeng J, Huang Q, Liu H, Xu W, et al. 2019. Next-generation genome sequencing of Sedum plumbizincicola sheds light on the structural evolution of plastid rRNA operon and phylogenetic implications within Saxifragales. Plants. 8(10):386.

- Guo S, Liao XJ, Chen SY, Liao BS, Guo YM, Cheng RY, Xiao SM, Hu HY, Chen J, Pei J, et al. 2022. A comparative analysis of the chloroplast genomes of four polygonum medicinal plants. Front Genet. 13:764534.

- Jin JJ, Yu WB, Yang JB, Song Y, dePamphilis CW, Yi TS, Li DZ. 2020. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 21(1):241.

- Kang H, Kim BY, Lee HR, Park YJ, Kim KA, Cheon KS. 2022. Characterization of the chloroplast genome of Meterostachys sikokianus (Makino) Nakai (Crassulaceae) and its phylogenetic analysis. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7(1):46–48.

- Lakshmanan A, Heath BP, Perlmutter A, Elder M. 2011. The impact of science content and professional learning communities on science teaching efficacy and standards‐based instruction. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 48(5):534–551.

- Li J, Chen D. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of medicinal plant, Sedum oryzifolium. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 5(3):2301–2302.

- Mascarello M, Amalfi M, Asselman P, Smets E, Hardy OJ, Beeckman H, Janssens SB. 2021. Genome skimming reveals novel plastid markers for the molecular identification of illegally logged African timber species. PloS One. 16(6):e0251655.

- Meng LM, Wan XL, Li LY, Hu J, Chen P. 2019. Screening of antitumor effective extracts from Sedum bulbiferum Makino and HPLC determination of quercetin and kaempferol in this herbal medicine. Med Plants. 10(3):30–33.

- Messerschmid TF, Klein JT, Kadereit G, Kadereit JW. 2020. Linnaeus’s folly–phylogeny, evolution and classification of Sedum (Crassulaceae) and Crassulaceae subfamily Sempervivoideae. Taxon. 69(5):892–926.

- Nah G, Jeong JR, Lee JH, Soh SY, Nam SY. 2022. The complete chloroplast genome of Echeveria lilacina Kimnach & Moran 1980 (Saxifragales: Crassulaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7(5):889–891.

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 32(1):268–274.

- Rozewicki J, Li S, Amada KM, Standley DM, Katoh K. 2019. MAFFT-DASH: integrated protein sequence and structural alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1):W5–W10.

- Seo HS, Kim SC. 2018. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Phedimus Kamtschaticus (Crassulaceae) in Korea. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 3(1):227–228.

- Seo HS, Kim SH, Kim SC. 2020. Chloroplast DNA insights into the phylogenetic position and anagenetic speciation of Phedimus takesimensis (Crassulaceae) on Ulleung and Dokdo Islands, Korea. PLoS One. 15(9):e0239734.

- Shi LC, Chen HM, Jiang M, Wang LQ, Wu X, Huang LF, Liu C. 2019. CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1):W65–W73.

- Tang Y, Zhang H, Xu X, Chang H. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Sedum lineare (crassulaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(12):3338–3339.

- Wu ZY, Raven PH. 2001. Flora of China. Vol. 8. Beijing: Brassicaceae through Saxifragaceae. Science Press.

- Zhang G, Liu Y. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome of the Tibetan medicinal plant Rhodiola kirilowii. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(1):222–223.

- Zhao DN, Ren CQ, Zhang JQ. 2021. Can plastome data resolve recent radiations? Rhodiola (Crassulaceae) as a case study. Bot J Linn Soc. 197(4):513–526.

- Zhao DN, Ren Y, Zhang JQ. 2020. Conservation and innovation: plastome evolution during rapid radiation of Rhodiola on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 144:106713.

- Zhao K, Li L, Quan H, Yang J, Zhang Z, Liao Z, Lan X. 2022. Comparative analyses of chloroplast genomes from Six Rhodiola species: variable DNA markers identification and phylogenetic inferences. BMC Genomics. 23(1):1–11.