Abstract

Elephantopus scaber L. is a useful medicinal plant and has been used as a traditional medicine for various diseases in Asia. In this study, we completed and characterized the chloroplast genome of E. scaber of which the length was 152,375 bp. This circular genome had a large-single copy (LSC, 83,520 bp), a small-single copy (SSC, 18,523 bp), and two inverted repeat regions (IR, 25,166 bp). There were 80 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes, and four rRNA genes in the chloroplast genome of E. scaber. Phylogenetic analysis inferred from 80 protein-coding regions revealed a close relationship between E. scaber and Cyanthillium cinereum (L.) H.Rob. and a sister relationship between Vernonioideae and Cichorioideae subfamilies. The genomic data of E. scaber provide useful information to explore the molecular evolution of not only Elephantopus genus but also the Asteraceae family.

1. Introduction

Elephantopus scaber L. 1753 is one of 21 members in Elephantopus genus of the Asteraceae family (POWO, Citation2023). This species has been used as a traditional medicine in many Asian countries such as Thailand, China, Vietnam, and Indonesia (Silalahi, Citation2021; Phumthum and Sadgrove, Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2014). Various compounds have been identified in different parts of E. scaber, such as sesquiterpene lactones, hexadecanoic acid, tetramethylhexadecenol, and yellowish essential oil (Hiradeve and Rangari, Citation2014). Previous studies revealed the anticancer capacity of E. scaber extract through activating apoptosis (Chan et al. Citation2016; Chan et al. Citation2015). Additionally, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, boosting immunity, hepatoprotective efficacy, and treating musculoskeletal disorders were found as features of E. scaber extract (Aldi et al. Citation2021; Kantasrila et al. Citation2020; Nguyen et al. Citation2020; Nguyen and Phan, Citation2022; Qi et al. Citation2020). Recently, E. scaber and other medicinal plants were found to be effective in treating mild COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, cough, diarrhea, headache, sore throat, and muscle pain (Phumthum et al. Citation2021). Although different effects of E. scaber have been reported, its genomic data (i.e. chloroplast, mitochondrial, and nuclear genomes) have not been explored.

Chloroplast genome (cpDNA) is an essential part of photosynthetic angiosperms and has been completed and characterized for many species of angiosperms (Daniell et al. Citation2016; Fahrenkrog et al. Citation2022; Li et al. Citation2023; Wang et al. Citation2022). Besides containing genes related to the photosynthesis process, cpDNA provides crucial data for reconstructing phylogeny, exploring evolutionary patterns, and developing molecular markers (Gitzendanner et al. Citation2018; Li et al. Citation2020; Smith, Citation2017; Yang et al. Citation2021). The genomic data of chloroplast genomes In Asteraceae, various complete cpDNAs have been published (Kim et al. Citation2023; Siu et al. Citation2022; Zhang et al. Citation2023; Zhou et al. Citation2021). Particularly, the complete cpDNAs of 11 species in the tribe Senecioneae of Asteraceae provided essential data for developing DNA barcodes (Gichira et al. Citation2019). Other previous studies examined phylogenetic relationships among members of Asteraceae based on chloroplast genome sequences (Fu et al. Citation2016; Siniscalchi et al. Citation2019; Y. Zhang et al. Citation2019). Although there are approximately 1930 species, only two complete cpDNAs of Cyanthillium cinereum (L.) H.Rob. and Gymnanthemum amygdalinum (Delile) Sch. Bip. were reported in Vernonioideae (Zhou et al. Citation2021; Siu et al. Citation2022). Therefore, in this study, the chloroplast genome of E. scaber was completed and characterized using the next-generation sequencing method. Additionally, the phylogenetic relationship between E. scaber and related species in Asteraceae inferred from 80 protein-coding regions was reconstructed using the maximum likelihood and bayesian inference methods (Ronquist et al. Citation2012; Huelsenbeck, Citation2019; Minh et al. Citation2020).

2. Materials and methods

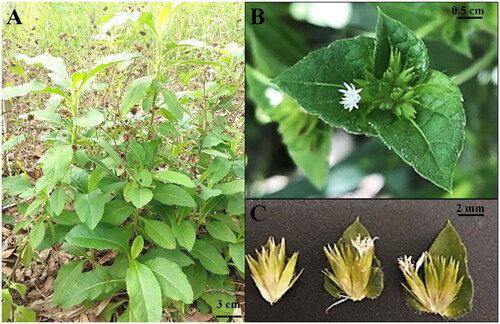

Fresh leaves of E. scaber were collected at Can Tho University Campus 2, Can Tho city, Vietnam (N10°01'53.5″, E105°46'16.6″) and dried in silica gel beads (). No specific permission was required to collect E. scaber because this species is considered a common medicinal plant in Vietnam. The voucher specimen was stored at the Institute of Food and Biotechnology, Can Tho University (contact person: Dr. Nguyen Pham Anh Thi; email: [email protected]; under voucher number BRDI-THI 20210531-002). The dried leaves were used to extract total genomic DNA using Dneasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA). The quality of DNA sample was checked using agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA spectrophotometers. The high-quality DNA (having a clear band on the agarose gel and concentration over 100 ng/ul; A260/280 and A260/230 ratios in a range of 1.8 − 2.0 and 2.0 − 2.2, respectively) was used for preparing a sequencing library with a TruSeq Nano DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA). The library was used for the Illumina MiSeq platform to generate paired-end reads of 301 bp in length. NOVOPlasty program was used to assemble the complete chloroplast genome of E. scaber (Dierckxsens, Mardulyn and Smits, Citation2017). Gene composition of E. scaber chloroplast genome was annotated using Geseq program (Tillich et al. Citation2017). The map of E. scaber chloroplast genome was illustrated using OGDRAW (Greiner et al. Citation2019). The complete chloroplast genome of E. scaber (average coverage depth = 148x, Supplementary Figure S1) was deposited to GenBank with accession number OL889925. For phylogenetic analysis, 80 protein-coding regions were extracted from 28 chloroplast genomes of Asteraceae species with sequences of Barnadesia lehmannii Hieron. as an outgroup. The extracted sequences were then aligned using MUSCLE embedded in Geneious Prime 2022.2 (www.geneious.com). The jModeltest 2.1.10 was used to check the best model for the data matrix and the best model was TVM + I + G (Akaike information criteria) (Darriba et al. Citation2012). The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using IQTREE with 1000 ultrafast bootstraps (Minh et al. Citation2020). Meanwhile, Mr. Bayes 3.2.7a was used to construct a bayesian inference phylogenetic tree with 1,000,000 generations (Ronquist et al. Citation2012). The phylogenetic tree was illustrated using Figtree v1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Figure 1. The photo of the whole plant Elephantopus scaber. (A) The whole plant. (B) The capitulum inflorescence. (C) The flowers. Morphological characteristics: Stem with patent or ascending white hairs, spatulate or oblanceolate leaves arranged in a rosette-like shape and having pilose above and beneath, capitulum inflorescence with pale mauve to white flowers (POWO, Citation2023). the photo was self-taken by the first author at Can Tho University, Can Tho city, Vietnam.

3. Results

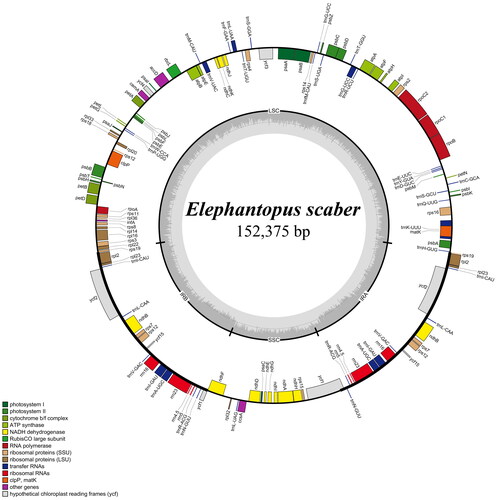

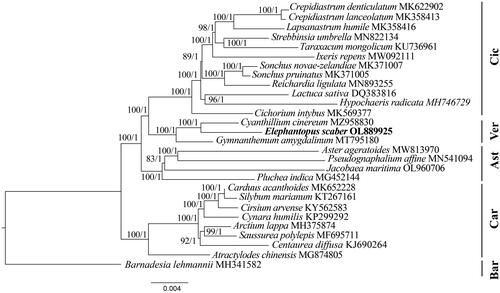

The complete chloroplast genome of E. scaber was 152,375 bp in length, and the GC content was 37.8% (). This quadripartite genome included a large-single copy (LSC, 83,520 bp), a small-single copy (SSC, 18,523 bp), and two inverted repeat regions (IR, 25,166 bp). This genome contained 80 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes, and four rRNA genes, of which 17 regions (including trnN_GUU, trnR_ACG, rrn5S, rrn4.5S, rrn23S, rrn16S, trnV_UAC, trnI_GAU, trnV_GAC, rps12, rps7, ndhB, trnL_CAA, ycf2, trnI_CAU, rpl23, and rpl2) were completely duplicated. There were ten protein-coding genes containing one intron and three protein-coding genes having two introns (Supplementary Figure S2 and S3). The junction between SSC and IR regions is located within ycf1 coding region whereas the boundary of LSC and IR regions is distributed within rps19 gene (). The results of Maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference methods revealed the same topology trees. Additionally, phylogenetic analysis revealed a monophyly of Vernonioideae taxa and a close relationship between Cichorioideae and Vernonioideae members (). Within Vernonioideae, E. scaber exhibited a sister relationship to Cyanthillium cinereum (L.) H.Rob. with high support values (bootstrap value = 100, posterior probability = 1).

Figure 2. Map of the E. scaber chloroplast genome. Genes shown inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, and those outside the circle are counterclockwise transcribed otherwise. The light grey and the darker grey in the inner circle correspond to at and GC content, respectively. Different functional groups are signed according to the colored legend. LSC: large single copy, SSC: small single copy; IRA/IRB: Inverted repeat regions.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree of E. scaber and 27 related species in Asteraceae inferred from 80 protein-coding regions of chloroplast genomes using Maximum likelihood and Bayesian Inference methods. Note: The best substitution model was TVM + I + G (Akaike information criteria). The numbers indicate the bootstrap values and posterior probabilities. The scale bar means the expected number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The chloroplast genome of Barnadesia lehmannii was used as an outgroup. Ast: Asteroideae; Bar: Barnadesioideae; Car: Carduoideae; Cic: Cichorioideae; Ver: Vernonioideae. The following sequences were used: Crepidiastrum denticulatum MK622902 (Do et al. Citation2019), Crepidiastrum lanceolatum MK358413 (Kim et al., Citation2019), lapsanastrum humile MK358416, Strebbinsia umbrella MN822134 (Lv et al. Citation2020), taraxacum mongolicum KU736961 (Kim et al. Citation2016), ixeris repens MW092111 (Lee et al. Citation2021), Sonchus novae-zelandiae MK371007, Sonchus pruinatus MK371005, Reichardia ligulata MN893255 (Cho et al. Citation2020), Lactuca sativa DQ383816 (Timme et al. Citation2007), Hypochaeris radicata MH746729, cichorium intybus MK569377 (Yang et al. Citation2019), Cyanthillium cinereum MZ958830 (Siu et al. Citation2022), Gymnanthemum amygdalinum MT795180 (Zhou et al. Citation2021), Aster ageratoides MW813970 (Feng et al. Citation2021), Pseudognaphalium affine MN541094 (Xie et al., Citation2021), Jacobaea maritima OL960706 (Zhang and Gong, Citation2023), Pluchea indica MG452144 (Zhang et al. Citation2017), Carduus acanthoides MK652228 (Jung et al. Citation2021), Silybum marianum KT267161 (Shim et al. Citation2020), Cirsium arvense KY562583 (Dann et al. Citation2017), Cynara humilis KP299292 (Curci and Sonnante, Citation2016), Arctium lappa MH375874 (Xing et al. Citation2019), Saussurea polylepis MF69571 (Yun et al., Citation2017), Centaurea diffusa KJ690264 (Turner et al. Citation2021), Atractylodes chinensis MG874805 (Wang et al. Citation2020), Barnadesia lehmannii MH341582.

4. Discussion and conclusion

This study characterizes the complete chloroplast genome of E. scaber, which is similar to those of other species in Asteraceae regarding gene content and structure. Previously, two simultaneous inversions of trnS_CGA-trnE_UUC (22.8 kb) and trnE_UUC-trnC_GCA (3.3 kb) regions in Asteraceae (except Barnadesioideae members) were reported (Kim, Choi and Jansen, Citation2005). These inversions were also found in the cpDNA of E. scaber. Furthermore, the phylogenetic analysis revealed the relationship between Asteroideae, Cichorioideae, and Vernonioideae, which is similar to the previous study (Fu et al. Citation2016). Phylogenetic relationships among members of Vernonioideae and related species were also explored based on 700 nuclear markers, morphological data, and protein-coding regions of cpDNAs (Tellería, Citation2012; Bunwong et al. Citation2014; Fu et al. Citation2016; Salamah et al. Citation2018; Siniscalchi et al. Citation2019). At present, although 80 protein-coding regions were employed for phylogenetic analysis, only three available complete cpDNAs of Vernonioideae members were used. Therefore, further studies covering more samples should be conducted to provide a deeper understanding of the evolution of this subfamily. The newly completed cpDNA of E. scaber will provide essential information for developing molecular markers, tracing evolutionary history, and reconstructing the phylogeny of the Elephantopus genus and the Asteraceae family.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The collection of Elephantopus scaber does not require specific permissions or licenses from the government and local governors. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Data availability statement

The genome sequence data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov] (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under accession no. OL889925. The associated BioProject, SRA, and Bio-Sample numbers are PRJNA788207, SRP350401, and SAMN23931738, respectively.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldi, Yufri, Dillasamola, Dwisari, Megaraswita,. (2021) ‘Effect of Elephantopus scaber Linn. leaf extract on mouse immune system’. Trop. J. Pharm Res, 18(10): 2045–2050. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v18i10.7.

- Bunwong S, Chantaranothai P, Keeley S. 2014. Revisions and key to the Vernonieae (Compositae) of Thailand. PhytoKeys. 37(37):25–101. doi:10.3897/phytokeys.37.6499.

- Chan CK, Chan G, Awang K, Abdul Kadir H. 2016. Deoxyelephantopin from Elephantopus scaber Inhibits HCT116 human colorectal carcinoma cell growth through apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Molecules. 21(3):385. doi:10.3390/molecules21030385.

- Chan CK, Supriady H, Goh BH, Kadir HA. 2015. Elephantopus scaber induces apoptosis through ROS-dependent mitochondrial signaling pathway in HCT116 human colorectal carcinoma cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 168:291–304. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.072.

- Cho M-S, Kim S-H, Yang J, Crawford DJ, Stuessy TF, López-Sepúlveda P, Kim S-C. 2020. Plastid phylogenomics of dendroseris (Cichorieae; Asteraceae): insights into structural organization and molecular evolution of an endemic lineage from the Juan Fernández Islands. Front Plant Sci. 11:594272. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.594272.

- Curci PL, Sonnante G. 2016. The complete chloroplast genome of Cynara humilis. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp Seq Anal. 27(4):2345–2346. doi:10.3109/19401736.2015.1025257.

- Daniell H, Lin C-S, Yu M, Chang W-J. 2016. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 17(1):134. doi:10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2.

- Dann M. 2017. ‘ Mutation rates in seeds and seed-banking influence substitution rates across the angiosperm phylogeny. bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/156398.

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. 2012. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 9(8):772–772. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2109.

- Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. 2017. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(4):e18. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw955.

- Do HDK, Jung J, Hyun J, Yoon SJ, Lim C, Park K, Kim J-H. 2019. The newly developed single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers for a potentially medicinal plant, Crepidiastrum denticulatum (Asteraceae), inferred from complete chloroplast genome data. Mol Biol Rep. 46(3):3287–3297. doi:10.1007/s11033-019-04789-5.

- Fahrenkrog AM, Matsumoto GO, Toth K, Jokipii-Lukkari S, Salo HM, Häggman H, Benevenuto J, Munoz PR. 2022. Chloroplast genome assemblies and comparative analyses of commercially important Vaccinium berry crops. Sci Rep. 12(1):21600. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-25434-5.

- Feng J-Y, Wu Y-Z, Wang R-R, Xiao X-F, Wang R-H, Qi Z-C, Yan X-L. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome of balsam aster (Aster ageratoides Turcz. var. scaberulus (Miq.) Ling., Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(9):2464–2465. doi:10.1080/23802359.2021.1955030.

- Fu Z-X, Jiao B-H, Nie B, Zhang G-J, Gao T-G. 2016. A comprehensive generic-level phylogeny of the sunflower family: implications for the systematics of Chinese Asteraceae. J Sytem Evol. 54(4):416–437. doi:10.1111/jse.12216.

- Gichira AW, Avoga S, Li Z, Hu G, Wang Q, Chen J. 2019. Comparative genomics of 11 complete chloroplast genomes of Senecioneae (Asteraceae) species: DNA barcodes and phylogenetics. Bot Stud. 60(1):17. doi:10.1186/s40529-019-0265-y.

- Gitzendanner MA, Soltis PS, Wong GK-S, Ruhfel BR, Soltis DE. 2018. Plastid phylogenomic analysis of green plants: a billion years of evolutionary history. Am J Bot. 105(3):291–301. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1048.

- Greiner S, Lehwark P, Bock R. 2019. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1):W59–W64. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz238.

- Hiradeve SM, Rangari VD. 2014. Elephantopus scaber Linn.: a review on its ethnomedical, phytochemical and pharmacological profile. J Appl Biomed. 12(2):49–61. doi:10.1016/j.jab.2014.01.008.

- Huelsenbeck JP. 2019. Phylogeny estimation using likelihood‐based methods. In Handbook of Statistical Genomics. Chichester, UK: Wiley, p. 177–218. doi:10.1002/9781119487845.ch6.

- Jung J, Do HDK, Hyun J, Kim C, Kim J-H. 2021. Comparative analysis and implications of the chloroplast genomes of three thistles (Carduus L., Asteraceae). Peer J. 9:e10687. doi:10.7717/peerj.10687.

- Kantasrila R, Pandith H, Balslev H, Wangpakapattanawong P, Panyadee P, Inta A. 2020. Medicinal plants for treating musculoskeletal disorders among Karen in Thailand. Plants. 9(7):811. doi:10.3390/plants9070811.

- Kim HT, Pak J-H, Kim JS. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Crepidiastrum lanceolatum (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1404–1405. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1598799.

- Kim J-K, Park JY, Lee YS, Woo SM, Park H-S, Lee S-C, Kang JH, Lee TJ, Sung SH, Yang T-J, et al. 2016. The complete chloroplast genomes of two Taraxacum species, T. platycarpum Dahlst. and T. mongolicum Hand.-Mazz. (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 1(1):412–413. doi:10.1080/23802359.2016.1176881.

- Kim JE, Kim S-C, Jang JE, Gil H-Y. 2023. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Adenostemma madurense (Asteraceae). J Asia-Pac Biodivers. doi:10.1016/j.japb.2023.01.005.

- Kim K-J, Choi K-S, Jansen RK. 2005. Two chloroplast DNA inversions originated simultaneously during the early evolution of the sunflower family (Asteraceae). Mol Biol Evol. 22(9):1783–1792. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi174.

- Lee W, Yang J, Kim S-C, Pak J-H. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of coastal psammophyte, Ixeris repens (Asteraceae, subtribe Crepidinae), in Korea. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(3):1050–1052. doi:10.1080/23802359.2021.1899076.

- Li C, Zheng Y, Huang P. 2020. Molecular markers from the chloroplast genome of rose provide a complementary tool for variety discrimination and profiling. Sci Rep. 10(1):12188. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-68092-1.

- Li E, Liu K, Deng R, Gao Y, Liu X, Dong W, Zhang Z. 2023. Insights into the phylogeny and chloroplast genome evolution of Eriocaulon (Eriocaulaceae). BMC Plant Biol. 23(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04034-z.

- Lv Z-Y, Zhang J-W, Chen J-T, Li Z-M, Sun H. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome of Soroseris umbrella (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5(1):637–638. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1711223.

- Silalahi M. 2021. ‘Utilization of Elephantopus scaber as traditional medicine and its bioactivity’, GSC Biol Pharm. Sci., 15(1):112–118. doi:10.30574/gscbps.2021.15.1.0106.

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, Lanfear R. 2020. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol. 37(5):1530–1534. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa015.

- Nguyen THP, Do TK, Nguyen TTN, Phan TD, Phung TH. 2020. Acute toxicity, antibacterial and antioxidant abilities of Elephantopus mollis H.B.K. and Elephantopus scaber L. CTU J. of Inn. & Sus. Dev.. 12(2):9–14. doi:10.22144/ctu.jen.2020.010.

- Nguyen THP, Phan TD. 2022. A study on antibacterial, antioxidant, and hepatoprotective efficacy of Elephantopus scaber L. JSM. 51(12):4031–4041. doi:10.17576/jsm-2022-5112-13.

- Phumthum M, Nguanchoo V, Balslev H. 2021. Medicinal plants used for treating mild covid-19 symptoms among Thai Karen and Hmong. Front Pharmacol. 12:699897. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.699897.

- Phumthum M, Sadgrove NJ. 2020. High-value plant species used for the treatment of “fever” by the karen hill tribe people. Antibiotics. 9(5):220. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9050220.

- POWO. 2023. Plants of the World Online. (Accessed 2023 May 1). Available at: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/.

- Qi R, Li X, Zhang X, Huang Y, Fei Q, Han Y, Cai R, Gao Y, Qi Y. 2020. Ethanol extract of Elephantopus scaber Linn. Attenuates inflammatory response via the inhibition of NF-κB signaling by dampening p65-DNA binding activity in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. J Ethnopharmacol. 250:112499. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112499.

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP, et al. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 61(3):539–542. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys029.

- Salamah ANDI, Oktarina R, Ambarwati EA, Putri DF, Dwiranti A, Andayani N. 2018. Chromosome numbers of some Asteraceae species from Universitas Indonesia Campus, Depok, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 19(6):2079–2087. doi:10.13057/biodiv/d190613.

- Shim J, Han J-H, Shin N-H, Lee J-E, Sung J-S, Yu Y, Lee S, Ahn KH, Chin JH. 2020. Complete chloroplast genome of a milk thistle (Silybum marianum) Acc. “912036. Plant Breed Biotech. 8(4):439–444. doi:10.9787/PBB.2020.8.4.439.

- Siniscalchi CM, Loeuille B, Funk VA, Mandel JR, Pirani JR. 2019. Phylogenomics yields new insight into relationships within Vernonieae (Asteraceae). Front Plant Sci. 10:1224. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01224.

- Siu T-Y, Wong K-H, Kong BL-H, Wu H-Y, But GW-C, Shaw P-C, Lau DT-W. 2022. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of Cyanthillium cinereum (L.) H. Rob. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7(6):1024–1026. doi:10.1080/23802359.2022.2080602.

- Smith DR. 2017. Evolution: in chloroplast genomes, anything goes. Curr Biol. 27(24):R1305–R1307. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.049.

- Tellería MC. 2012. Palynological survey of the subtribe Elephantopinae (Asteraceae, Vernonieae). Plant Syst Evol. 298(6):1133–1139. doi:10.1007/s00606-012-0625-5.

- Tillich M, Lehwark P, Pellizzer T, Ulbricht-Jones ES, Fischer A, Bock R, Greiner S. 2017. GeSeq – versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(W1):W6–W11. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx391.

- Timme RE, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2007. A comparative analysis of the Lactuca and Helianthus (Asteraceae) plastid genomes: identification of divergent regions and categorization of shared repeats. Am J Bot. 94(3):302–312. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.3.302.

- Turner KG, Ostevik KL, Grassa CJ, Rieseberg LH. 2021. Genomic analyses of phenotypic differences between native and invasive populations of diffuse knapweed (Centaurea diffusa). Front Ecol Evol. 8:577635. doi:10.3389/fevo.2020.577635.

- Wang J, Li P, Li B, Guo Z, Kennelly EJ, Long C. 2014. Bioactivities of compounds from Elephantopus scaber, an ethnomedicinal plant from southwest China. Evidence-Based Complementary Alternative Medicine. 2014:1–7. doi:10.1155/2014/569594.

- Wang L, Zhang H, Wu X, Wang Z, Fang W, Jiang M, Chen H, Huang L, Liu C. 2020. Phylogenetic relationships of Atractylodes lancea, A. chinensis and A. macrocephala, revealed by complete plastome and nuclear gene sequences. PLoS One. 15(1):e0227610. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227610.

- Wang X, Dorjee T, Chen Y, Gao F, Zhou Y. 2022. The complete chloroplast genome sequencing analysis revealed an unusual IRs reduction in three species of subfamily Zygophylloideae. PLoS One. 17(2):e0263253. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0263253.

- Xie L, Zhao J, Liu R. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome of Pseudognaphalium affine (D. Don) Anderb. (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(11):3276–3277. doi:10.1080/23802359.2021.1993104.

- Xing Y-P, Xu L, Chen S-Y, Liang Y-M, Wang J-H, Liu C-S, Liu T, Kang T-G. 2019. Comparative analysis of complete chloroplast genomes sequencesof Arctium lappa and A. tomentosum. Biologia Plant. 63:565-574. doi:10.32615/bp.2019.101.

- Yang Q, Fu G-F, Wu Z-Q, Li L, Zhao J-L, Li Q-J. 2021. Chloroplast genome evolution in four montane zingiberaceae taxa in China. Front Plant Sci. 12:774482. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.774482.

- Yang S, Sun X, Wang L, Jiang X, Zhong Q. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1533–1534. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1601524.

- Yun SA, Gil H-Y, Kim S-C. 2017. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Saussurea polylepis (Asteraceae), a vulnerable endemic species of Korea. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2(2):650–651. doi:10.1080/23802359.2017.1375881.

- Zhang K, Gong S. 2023. The complete chloroplast genome and phylogenetic analysis of Jacobaea maritima (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 8(7):771–776. doi:10.1080/23802359.2023.2238937.

- Zhang N, Xie P, Huang K, Yin H, Mo P, Wang Y. 2023. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Centaurea cyanus (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 8(3):393–397. doi:10.1080/23802359.2023.2185470.

- Zhang Y, Zhang J, Yang Y, Liu Q. 2017. Complete chloroplast genome of Pluchea indica (L.) Less. (Asteraceae) and its phylogenetic analysis. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2(2):918–919. doi:10.1080/23802359.2017.1413299.

- Zhang Y-b, Yuan Y, Pang Y-x, Yu F-l, Yuan C, Wang D, Hu X. 2019. Phylogenetic reconstruction and divergence time estimation of blumea DC. (Asteraceae: inuleae) in China based on nrDNA ITS and cpDNA trnL-F sequences. Plants. 8(7):210. doi:10.3390/plants8070210.

- Zhou F, Lan K, Li X, Mei Y, Cai S, Wang J. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Vernonia amygdalina Delile. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(3):1134–1135. doi:10.1080/23802359.2021.1902411.