ABSTRACT

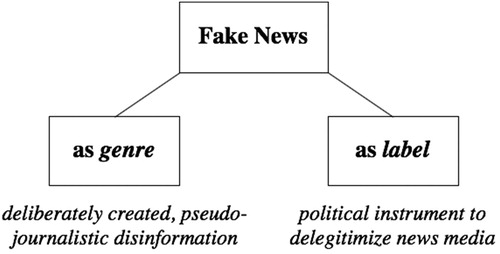

Based on an extensive literature review, we suggest that ‘fake news’ alludes to two dimensions of political communication: the fake news genre (i.e. the deliberate creation of pseudojournalistic disinformation) and the fake news label (i.e. the instrumentalization of the term to delegitimize news media). While public worries about the use of the label by politicians are increasing, scholarly interest is heavily focused on the genre aspect of fake news. We connect the existing literature on fake news to related concepts from political communication and journalism research, present a theoretical framework to study fake news, and formulate a research agenda. Thus, we bring clarity to the discourse about fake news and suggest shifting scholarly attention to the neglected fake news label.

Introduction

The so-called ‘fake news’ crisis has been one of the most discussed topics in both public and scientific discourse since the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign (Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018). While the term fake news was originally applied to political satire (e.g. Baym, Citation2005), it now seems to stand for all things ‘inaccurate’ (e.g. Lazer et al., Citation2017; Tambini, Citation2017) and is even applied in contexts that are completely unrelated to mediated communication (e.g. in research articles such as ‘Are Meta-Analyses a Form of Medical Fake News?’ Packer, Citation2017). What fake news stands for, however, is something larger than the term itself: a fundamental shift in political and public attitudes to what journalism and news represent and how facts and information may be obtained in a digitalized world.

The purpose of this paper is to restructure the existing literature and future research efforts dealing with the phenomenon of ‘fake news’ at large. We posit that fake news is, in essence, a two-dimensional phenomenon of public communication: there is the (1) fake news genre, describing the deliberate creation of pseudojournalistic disinformation, and there is the (2) fake news label, describing the political instrumentalization of the term to delegitimize news media. While research on the genre is gaining attention, there is only limited research on the delegitimizing efforts visible in many Western democracies today. As the hype around fake news in terms of information and false news continues, the term has been effectively weaponized by political actors to attack a variety of news media (e.g. Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, Citation2018).

Based on the literature from journalism, political science, and communication research, we contextualize the two dimensions of fake news within the current political climate and describe how they relate to other concepts. In doing so, we suggest that ‘fake news’ is more than just an isolated event or a buzzword to be easily dismissed; it is the expression of a larger and fundamental shift within the technological and political underpinnings of mediated communication in modern democracies. Our review of the available empirical research on fake news as a genre and a label allows for future research to build on existing findings and contrasts these findings with existing concepts within the literature. We also offer a research agenda to meet unanswered challenges. With this extensive review, we bring clarity to the discourse surrounding fake news, and we suggest shifting scholarly attention to the neglected fake news label.

Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon

Condensing ‘a wide range of news-gathering practices into the same noun’ has been causing problems for definitions of ‘real news’ and journalism as a profession for a long time now (Carlson, Citation2017, p. 19). Along the same lines, overly general conceptualizations of the term ‘fake news’ can even be outright dangerous, as citizens struggle to distinguish legitimate news from fake news in a digital information environment (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; UNESCO, Citation2018). Even more importantly, research has begun to show that ‘fake’ news is often understood as news one does not believe in – thereby blurring the boundaries between facts and beliefs in a confusing digitalized world (Nielsen & Graves, Citation2017). Unhelpfully, scholars have been tempted to use the term to describe many different things, such as propagandistic messages from state-owned media (Khaldarova & Pantti, Citation2016), extreme partisan alternative media (e.g. Bakir & McStay, Citation2018), and fabricated news from short-lived websites (e.g. Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017). To make matters worse, political actors have seized the opportunity to use the term as a weapon to undermine any information that contradicts their own political agenda (e.g. Hanitzsch, Van Dalen, & Steindl, Citation2018; Nielsen & Graves, Citation2017; UN OSCE, OAS, & ACHPR, Citation2017). This instrumentalization of the term fake news by political actors is severely understudied.

We suggest to take a more guided approach, and argue that there is a fundamental difference between what constitutes fake news and what the term is used for: There is the fake news genre, describing the deliberate creation of pseudojournalistic disinformation, and the fake news label, namely, the instrumentalization of the term to delegitimize news media (see ).

The ‘fake news’ genre

The three pillars of fake news

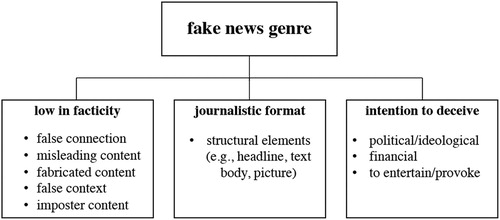

We reviewed the available studies that define fake news, resulting in three characteristics that must be fulfilled to classify something as fake news as opposed to other falsehoods, bad journalism, or simply mistakes in communication. As shown in , we argue that a message should only be studied as ‘fake news’ when it is low in facticity, was created with the intention to deceive, and is presented in a journalistic format.

Table 1. Overview of characteristics in fake news definitions.

Most authors agree that fake news contains false information. For example, Wardle (Citation2017) lists a variety of mis- and disinformation types that describe fake news, namely, news that contains ‘false connection, false context, manipulated content, misleading content (…)’. Along the same lines, Bakir and McStay (Citation2018, p. 157) describe fake news as ‘either wholly false or containing deliberately misleading elements incorporated within its content or context’. This means that the presence of facts does not disqualify a message as fake news, and that their content can be completely fabricated, but also only be partly untrue and paired with correct information. To date, no study has come up with a ratio of true to untrue information that describes when a message becomes ‘fake’. Therefore, the currently most accurate way of labelling this content feature is provided by Tandoc, Lim, and Ling (Citation2018), who state that fake news must be low in facticity, therefore implying that both fully as well as partly untrue messages can be fake news (see ).

Next, most authors argue that fake news ‘mimics news media content in form’ (Lazer et al., Citation2018, p. 1094) and is thus presented in a journalistic format. Considering the literal meaning of ‘fake’, as ‘not genuine; imitation or counterfeit,’ (Oxford Dictionaries, Citation2019), fake news does not simply mean false news but should be understood as an imitation of news. Thus, fake news consists of similar structural components: a headline, a text body, and (however, not necessarily) a picture (e.g. Horne & Adalı, Citation2017). Although most studies do not consider these forms (for an exception, see Khaldarova & Pantti, Citation2016), journalistic presentation can also involve video and radio news formats.Footnote1 By doing so, the information is presented under the false pretence that it resulted from journalistic research that follows certain professional standards, which means that fake news may be described as pseudojournalistic (see ). As a result, recipients might misattribute fake news articles as genuine and credible news articles (Mustafaraj & Metaxas, Citation2017; Vargo, Guo, & Amazeen, Citation2018). Importantly, Tandoc and colleagues note that, apart from the visual appearance of a news article, ‘through the use of news bots, fake news imitates news’ omnipresence by building a network of fake sites’ (Tandoc et al., Citation2018, p. 147).

Based on the assumption that no one inadvertently produces inaccurate information in the style of news articles, we also suggest – in line with several scholars – that the fake news genre is created deliberately with an intention to deceive (see ). Arguably, this can be seen as a ‘defining element of fake news’ (Lazer et al., Citation2018, p. 1095). Most scholars agree that the main motivations for deception are either political/ideological or financial (e.g. Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Bakir & McStay, Citation2018; Lazer et al., Citation2018; McNair, Citation2017; Tandoc et al., Citation2018). However, it is also possible that fake news is created for humorous reasons, to entertain, or as Wardle (Citation2017) dubs it, ‘to provoke’. In the context of intent, it is important to distinguish between two different processes: the creation of fake news and its dissemination (see also Wardle & Derakhshan, Citation2017). The creation of the fake news genre is always intentional, while the dissemination may be unintentional.

When thinking of this third characteristic, some thoughts on the potential source of fake news are warranted. The most obvious source of fake news are websites that are developed and ‘dedicated solely to propagating fake news’ (Vargo et al., Citation2018, p. 2031). These websites have names that imitate those of established news outlets (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017), e.g. ‘The Political Insider’ or ‘The Denver Guardian’.Footnote2 They are pseudojournalistic and short-lived, as ‘they do not attempt to build a long-term reputation for quality, but rather maximize the short-run profits from attracting clicks in an initial period’ (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017, pp. 218–19). While some websites emerged earlier, in the wake of the 2016 U.S. presidential election, a ‘tipping point’ was reached, and a large amount of fake news originated from these sites (Brennen, Citation2017, p. 180). By pretending to be legitimate news sources, these websites also perform with the intention to deceive their users.

Existing studies, however, have also considered satirical, alternative and partisan, pro-governmental, and mainstream journalism as sources of fake news (e.g. Bakir & McStay, 2017; Khaldarova & Pantti, Citation2016; Tambini, Citation2017). Additionally, public conceptions of the term include ‘poor journalism’, native advertising, and propaganda outlets (Nielsen & Graves, Citation2017). So, do some of the sources meet the above three characteristics (see )? Political satire presents factual information in the format of a TV news broadcast and makes deviations from truth and objectivity known (Baym, Citation2005; Tandoc et al., Citation2018). It is thus neither low in facticity nor created with the intention to deceive (see also HLEG, Citation2018). News parody, on the other hand, includes nonfactual information presented in the form of news articles (Tandoc et al., Citation2018). It thus deliberately distorts facts for amusement, not because it has the intention to deceive. News parody relies on the implicit assumption that the audience knows that the content is not true (Tandoc et al., Citation2018).Footnote3 Consequently, satire and news parody should be excluded from the current understanding of fake news (Baym, Citation2005; Borden & Tew, Citation2007; McNair, Citation2017; Tandoc et al., Citation2018). Next is native advertising (i.e. advertising that is presented as news reports in news media), which is created with the intention to deceive its audience to think they read a professionally researched journalistic product. However, native advertising is mostly factual (although focusing on positive information about the advertised article) (Tandoc et al., Citation2018); thus, it is not necessarily low in facticity. Consequently, native advertising does not fulfil all characteristics, and we therefore exclude it from the fake news genre. Another term that has been named as a source of fake news is ‘poor’ or ‘bad’ journalism, stemming from mainstream, alternative, partisan, or state-owned media. Journalists might introduce false information into media coverage by mistake because they believe it to be true (i.e. misperceptions) due to time pressure or too little editorial resources. However, those flaws are ‘not fake news, but consequence of the fact that journalism is a creative cultural practice undertaken by human beings in all their frailty and imperfection’ (McNair, Citation2017, p. 23). However, naturally, it is also possible that journalists deliberately distort facts and indeed have a personal or even organizational intention to deceive. On a personal level, this intention to deceive is difficult to estimate. Organizational deception among media with a track record of professional journalistic reporting may be possible. For example, studies could investigate, over time, if outlets repeatedly publish falsehoods on the same topic, without publishing rectifications. If an intention to deceive is shown, the term ‘poor’ journalism no longer applies, and the term fake news seems appropriate.

Table 2. Overview of how sources meet the conditions required to call their content ‘fake news’.

In conclusion, the third characteristic, intention to deceive, is the most challenging to grasp from a scholarly standpoint. While we consider the intention to deceive as inherently given in regard to pseudojournalistic fake news websites, we suggest that determining this intentionality for journalistic sources is a crucial challenge for future research. Moreover, an increasing number of scholars remark that the term fake news is insufficient in describing different types of disinformation (e.g. HLEG, Citation2018; Wardle & Derakhshan, Citation2017). We agree that a strict limitation on the use of this term is necessary, as terming everything connected to the much larger trend of disinformation in public life as ‘fake news’ simply contributes to the normalization of the fake news label as a political instrument, which – as we will elaborate on below – has detrimental consequences for democracies. Thus, we strongly recommend using the term fake news only when all three above-mentioned characteristics are met.Footnote4

How the fake news genre relates to other concepts

In the following, we embed the fake news genre within the comprehensive existing political communication literature. We show that, while it is of course not new in its essence, it represents a highly visible symptom of the longstanding increase in disinformation. Specifically, we refer to research on propaganda (Howard, Bolsover, Bradshaw, Kollanyi, & Neudert, Citation2017; Khaldarova & Pantti, Citation2016; Wardle, Citation2017), misinformation and disinformation (e.g. Lazer et al., Citation2017), rumours (Mihailidis & Viotty, Citation2017), and conspiracy theories (e.g. McNair, Citation2017).

Propaganda describes a specific and overarching class of communication that can be described as ‘the deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behaviour to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist’ (Jowett & O’Donnell, Citation2014, p. 7). In that way, any information – accurate or not – can be applied for propagandistic ambitions, and propagandists can be both a ‘state and non-state political actor’ (Neudert, Citation2017, p. 4). As opposed to the practice of persuasion, the true purpose of propaganda stays concealed. To achieve this purpose, propagandists aim to control the information flow, often by ‘presenting distorted information from what appears to be a credible source’ (Jowett & O’Donnell, Citation2014, p. 51). Importantly, in our context, by presenting false information in a journalistic format (e.g. stemming from a fake news website that resembles a medium or from a ‘poor’ journalistic source), the fake news genre can be applied for propagandistic intent. In this context, a study from Russia defines fake news as ‘strategic narratives’ from Channel One, a TV station owned by the Russian government (Khaldarova & Pantti, Citation2016). Similarly, other authors have described fake news as ‘pieces of propaganda’ (Waisbord, Citation2018, p. 1867) or as one of many computational and/or digital ‘instruments of a novel form of twenty-first century propaganda’ (Neudert, Citation2017, p. 4).

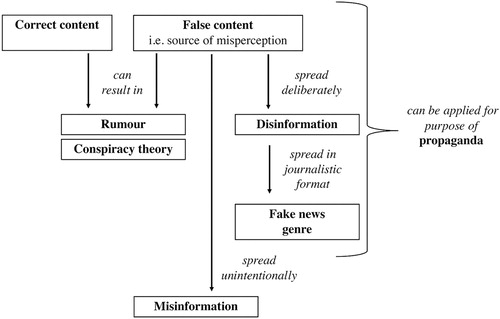

Fake news is most often discussed in the context of studying misinformation and disinformation. While sometimes used synonymously, misinformation describes incorrect or misleading information that is disseminated unintentionally, while disinformation is incorrect or misleading information that is disseminated deliberately (e.g. Bakir & McStay, Citation2018; HLEG, Citation2018; Lazer et al., Citation2018; Wardle & Derakhshan, Citation2017). Thus, while both share the characteristic of the inaccuracy of content, they can be distinguished by their intent. This makes disinformation particularly relevant for understanding fake news, and current debates are often concerned with the increase in organized, technologically reinforced disinformation in modern societies (e.g. HLEG, Citation2018; UNESCO, Citation2018). This is the case because exposure to mis- and disinformation can lead to persistent misperceptions, which have been shown to be difficult to correct (for an overview of misperception research, see Flynn, Reifler, & Nyhan, Citation2017). Today, such misperceptions are discussed as one important and concerning trend in many democracies following the fake news debate, with consequences for politics and popular opinions about science and medicine.

Rumours and conspiracy theories are two other concepts that have been mentioned in the context of fake news. They both originate from content, which is ‘unsupported by the best available evidence’ (Flynn et al., Citation2017, p. 129), and can arise not only from mis- or disinformation (including the fake news genre) but also from information that might turn out to be true. Rumours are mainly characterized by their lack of evidence and their ‘widespread social transmission’ (Berinsky, Citation2017, p. 243). Conspiracy theories can be distinguished from rumours by their ‘effort to explain some event or practice by reference to the machinations of powerful people, who attempt to conceal their role’ (Sunstein & Vermeule, Citation2009, p. 205). Using oversimplification, conspiracy theories help people make sense of complex matters and offer a personified source (i.e. ‘powerful people’) of injustice and sorrow in the world (Bale, Citation2007), and can lead to misperceptions (Lewandowsky, Ecker, & Cook, Citation2017). Rumours and conspiracy theories were around long before the emergence of fake news (e.g. McNair, Citation2017), but fake news can be used to spread information that supports rumours and conspiracy theories (e.g. Douglas, Ang, & Deravi, Citation2017).

In summary, we can place the fake news genre most comfortably within the disinformation literature – if disinformation is packaged in a journalistic format, it emerges as fake news. Disinformation, however, exceeds the concept of fake news, as it also involves numerous forms ‘that go well beyond anything resembling “news”’ (HLEG, Citation2018, p. 10). The consequence of exposure to fake news is therefore misperceptions. Rumours and conspiracy theories can result from both accurate and incorrect content (including misinformation, disinformation, and the fake news genre). Fake news may be (and is) used for propagandistic purposes. illustrates the relationship between the discussed concepts.

Where does the fake news genre come from?

We can pinpoint a number of trends that have contributed to the rise of the fake news genre. Disinformation in political discourse is of course not new; however, the extent to which it occurs today appears to be growing (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Lazer et al., Citation2017; Waisbord, Citation2018). Closely connected to the rise of the fake news debate are the challenges that the rise of the internet and social media present for modern democracies. In an online news environment, information may be created and spread more cost-efficiently and quicker than ever before, and audiences are now able to participate in news production and dissemination processes (e.g. Lazer et al., Citation2018; McNair, Citation2017; Tong, Citation2018; Waisbord, Citation2018). As a result, classic selection mechanisms, such as trust in the gatekeeping function of professional journalism, are impaired (e.g. McNair, Citation2017; Nielsen & Graves, Citation2017; Starr, Citation2012) not only because it is increasingly challenging to differentiate between professional and unprofessional content (Stanford History Education Group, Citation2016) but also because journalists themselves are now challenged in properly verifying digital information during the news production process (Lecheler & Kruikemeier, Citation2016). This challenge puts the assessment of information credibility increasingly with an overwhelmed user (Metzger, Flanagin, Eyal, Lemus, & Mccann, Citation2003), and studies show that even so-called ‘digital natives’ struggle with evaluating online information (Stanford History Education Group, Citation2016). In addition, digital advertising makes fake news financially attractive, as views or ‘clicks’ instead of the accuracy of the content create business success (e.g. Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Bakir & McStay, Citation2018; Tambini, Citation2017). This idea links fake news to the emergence of clickbait, i.e. the creation of news content solely aimed at generating attention through sensational and emotionally appealing headlines (Bakir & McStay, Citation2018).

These technological developments are met by a number of social and political trends: most scholars connect the emergence of fake news to a larger crisis of trust in journalism (e.g. Lazer et al., Citation2018; McNair, Citation2017; Nielsen & Graves, Citation2017). While most prominently discussed in the U.S., where a recent poll found that media trust has dropped to ‘a new low’ (Swift, Citation2016), increasing mistrust towards news media is also a problem (in varying degrees) in other countries (Newman, Fletcher, Kalogeropoulos, Levy, & Nielsen, Citation2017). Importantly, media trust is not decreasing for all citizens and rather has to be seen in the context of increasing political polarization. In the U.S., media perceptions are divided by partisanship, with Democrats having more positive attitudes towards the media than Republicans (e.g. Gottfried, Stocking, & Grieco, Citation2018; Guess, Nyhan, & Reifler, Citation2017). In Western Europe, citizens holding populist views are more likely to have negative opinions of news media compared to those holding non-populist views (Mitchell et al., Citation2018). However, for some, decreasing trust in traditional journalism might lead to a higher acceptance of other information sources, including fake news. Furthermore, increasing opinion polarization leads to homogenous networks, where opposing views are rare and the willingness to accept an ideology confirming news – true or false – is high (e.g. Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Lazer et al., Citation2018; Mihailidis & Viotty, Citation2017).

Empirical evidence on the fake news genre

The fast-growing empirical literature on fake news can be divided into three broad categories: (1) investigations on how fake news occurs within public discourse, (2) studies interested in effects, and (3) those that investigate how the spread of fake news can be counteracted. Importantly, for this review, we focus on studies that specifically consider ‘fake news’. In doing so, we repeatedly make connections to the related literature on mis- and disinformation, which provides the foundation for the study on the fake news genre (for overviews, see, e.g. Flynn et al., Citation2017; Lewandowsky et al., Citation2017).

Scholars interested in the occurrence of fake news in public discourse have investigated how many citizens such news actually reaches, its structure, the way it is spread on social media, and its content. In terms of its structure, fake news seems to be shorter and less informative than genuine news, using less complex and more personal language, and is likely to have longer titles, which contain the main claim of the article (Horne & Adalı, Citation2017). Fake news on social media is spread not only through social botsFootnote5 (Shao, Ciampaglia, Varol, Flammini, & Menczer, Citation2017) but also by humans (Mustafaraj & Metaxas, Citation2017).

Considering their content, Humprecht (Citation2018) finds that in the U.S. and U.K., fake news stories predominantly focus on political actors, while in Germany and Austria, sensational content about refugees is dominating. The author concludes that fake news content is strongly influenced by domestic news agendas. Consequently, it is not surprising that in 2016, U.S. fake news stories featuring one of the presidential candidates were prevalent. Of these articles, those favouring Donald Trump were shared more often than those favouring Hillary Clinton (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017). Some fake news stories received more likes and shares than actual news stories on Facebook and Twitter (Howard et al., Citation2017; Silverman, Citation2016). However, shares and likes on social media do not equal the actual consumption of fake news (Guess, Nyhan, & Reifler, Citation2018; Lazer et al., Citation2018). Several studies, therefore, have investigated how many citizens actually visited fake news sites in 2016 in the U.S. (Guess et al., Citation2018; Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018), as well as in 2017 in France and Italy (Fletcher, Cornia, Graves, & Nielsen, Citation2018). They consistently find that the actual audience of fake news sites is very limited in relation to the total U.S. population (Guess et al., Citation2018) and compared to the audience of established news sites in the U.S., France and Italy (Fletcher et al., Citation2018; Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018). Furthermore, established news sites are not only visited by more citizens, but their visitors also spend more time compared to visitors of fake news sites (Fletcher et al., Citation2018; Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018). Furthermore, the results suggest that Facebook plays a main role in encountering fake news (Guess et al., Citation2018; Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018).

So far, there are only a few effect studies on fake news. The results suggest that many citizens struggle to identify fake news, with Republicans and heavy Facebook news users being more likely to believe that such news is accurate compared to Democrats and those who rely more on other news sources (Silverman & Singer-Vine, Citation2016). Furthermore, repeated exposure to fake news headlines has been shown to increase their perceived accuracy (Pennycook, Cannon, & Rand, Citation2017). However, while a survey in December 2016 finds that two-thirds of Americans believe that fake news has caused ‘a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current issues and events’ (Mitchell, Barthel, & Holcomb, Citation2016), on an aggregate level, scholars have argued that fake news did not substantively altered the outcome of the 2016 U.S. elections (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017).

Other researchers focus on the role of fact-checking and computer-assisted methods to automatically detect fake news online. They find that there is simply less fact-checking compared to fake news content and that fact-checking is shared with a significant time delay after the spread of the original misinformation (Shao, Ciampaglia, Flammini, & Menczer, Citation2016). Moreover, ‘disputed by 3rd-party fact-checkers’ warnings on social media reduce the perceived accuracy of fake news stories only sparsely (Pennycook & Rand, Citation2017), and fact-checking sites do not seem to influence the issue agenda of other media (Vargo et al., Citation2018). These results suggest that fact-checking is not sufficiently effective to tackle the fake news problem. Computer-assisted methods to automatically detect fake news are often connected to the so-called ‘Fake News Challenge’ (FNC-1), a competition encouraging the exploration of artificial intelligence technologies for finding automated ways to detect fake news. Several scholars have submitted promising methods; however, research on automated detection is still developing and, thus far, inconclusive (Pomerleau & Rao, Citation2016).

In summary, we know that the fake news genre differs in some crucial aspects from genuine news and that it is mainly disseminated through social media, where such news gains a lot of attention in terms of likes and shares. The actual audience for such fake news, however, appears to be more limited than first anticipated. Few studies have considered whether citizens perceive fake news to be accurate, but research on its effects on attitudes is lacking. Furthermore, fact-checking has only a limited effect, while research on automated detection is still in need of development. These findings are limited by the fact that most interdisciplinary studies have been conducted in the U.S. context and specifically in the context of the 2016 presidential election (except for Fletcher et al., Citation2018; Humprecht, Citation2018).

The ‘fake news’ label

Today, fake news has become a negatively charged buzzword, acting as a reminder of the increase in falsehoods in a digitalized and fragmented information environment. However, at the same time, this associated negativity has rendered the term a potent weapon for a number of political actors, who now use it to discredit legacy news media that contradict their positions, suggesting that these outlets are politically biased (e.g. Vosoughi et al., Citation2018). Consequently, such weaponization of the term fake news has become a part of political instrumentalization strategies with the goal of undermining public trust in institutional news media as central parts of democratic political systems. As a political instrument, the fake news label thus portrays news media as institutions that purposely spread disinformation with the intention to deceive (see also Albright, Citation2017).

Politicians criticizing the media for being biased are not new (e.g. Ladd, Citation2012). However, the extent to which this happens following the introduction of the fake news terminology is unprecedented (e.g. Guess et al., Citation2017; McNair, Citation2017). Furthermore, stating that news media and their coverage are not only ideologically biased or factually incorrect but also fake is important to understand. Journalistic authority, or the ‘right to be listened to’ (Carlson, Citation2017, p. 8), is thus contested. Contrary to the standards of democratic debates, scholars have argued that the fake news label is not accompanied by explanations of why the accused media coverage is inaccurate or biased (McNair, Citation2017). Consequently, the fake news label is not applied to critically evaluate the coverage of a medium but rather to attack the outlet’s legitimacy (see also Lischka, Citation2019). Denner and Peter (Citation2017, p. 275) suggest that the ‘associated trivialization of a term carrying such negative connotations is problematic and could help to establish [it] as an unreflected designation for the media’. They speak of the German word ‘Lügenpresse’ (lying press), but the same holds true for the fake news label.

The most prominent example of this use of the term fake news is U.S. president Donald Trump, but it has also recently been applied by politicians in Austria, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Czech Republic, Egypt, France, Italy, Norway, Russia, South Africa, Turkey, the UK and many more (Newman, Fletcher, Kalogeropoulos, Levy, & Nielsen, Citation2018; RSF, Citation2017), highlighting its global significance.

The weaponization of the term fake news may have fundamental effects on the work of the news media beyond simple political debates. The United Nations and other observers of public life declared that they are ‘[a]larmed at instances in which public authorities denigrate, intimidate and threaten the media, including by stating that the media is “the opposition” or is “lying” and has a hidden political agenda’ (UN et al., Citation2017, p. 1). Reporters Without Borders (2018) warn that increasing ‘[h]ostility towards the media, openly encouraged by political leaders (…) pose a threat to democracies’. Additionally, scholars have noticed that publicly voiced media criticism by political actors is increasingly delegitimizing and to a greater extent characterized by hostility (e.g. Tong, Citation2018). Thus, the fake news label arguably represents the globally most visible symptom of a greater trend in political communication, namely, an increase in delegitimizing media criticism by political actors.

Such criticism goes hand in hand with other and well-known attempts to delegitimize journalism, such as when politicians deny ‘critical’ media access to press briefings (e.g. U.S. president Trump; Siddiqui, Citation2017) or generally restrict communication with them (e.g. Austria’s interior ministry; Möseneder, Citation2018). This delegitimization impedes the public function of journalism, the nature of political discourse, and the democratic process in general (e.g. Matthes, Maurer, & Arendt, Citation2019; Pfetsch, Citation2004; Tsfati, Citation2014). This increasing political antagonism is also likely to have a direct effect on journalists’ work. For example, a number of authoritarian leaders use the terminology of a ‘fight against fake news’ to justify their censorship policies (RSF, Citation2017). Moreover, verbal attacks might also affect journalists in terms of self-censorship for fear of criticism. Self-censorship can ‘occur when a decision to suppress information is made within the media organization, but as a result of pressure from the outside’ (George, Citation2018, p. 480). Importantly in this context, a survey of journalists in Sweden – a country with stable press freedom – recently showed that verbal threats and abusive comments indeed lead to journalists avoiding certain topics or actors in their coverage (Löfgren Nilsson & Örnebring, Citation2016).

Furthermore, considering the importance of elite rhetoric for opinion formation, political media criticism might influence how citizens perceive the media (e.g. Ladd, Citation2012). Research shows that political attacks can increase perceptions of media bias (Smith, Citation2010) and decrease levels of media trust (Ladd, Citation2012).

How the fake news label relates to other concepts

The weaponized fake news label can be understood in the context of existing theories of political communication. As stated above, propaganda can be characterized as a form of communication that aims at shaping public opinion in a way that gratifies the propagandist’s concealed agenda (e.g. Jowett & O’Donnell, Citation2014). One way to influence public opinion is through ‘controlling the media as a source of information distribution’ (Jowett & O’Donnell, Citation2014, p. 51). In this sense, the fake news label may be understood as an attempt to control the media’s influence on the public.

Similarly, the fake news label can be connected to research on media criticism, understood as a non-academic critique of journalism. Media criticism can be seen as a substantial part of metajournalistic discourse, i.e. publicly verbalized evaluations of the quality of journalistic processes and products. Within metajournalistic discourse, actors inside and outside of journalism compete over the definitions, boundaries, and legitimacy of journalism (Carlson, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018). Media criticism – in its ideal state – has a democratic function, as it serves to evaluate media quality and to control if the media is fulfilling its role in democratic societies (Carey, Citation1974; Carlson, Citation2018; Wyatt, Citation2007). Here, criticism is used to deprecate violations of journalistic norms and differentiate them from ‘good’ journalism, reinforcing the legitimacy of journalism at large (Carlson, Citation2009). To be ‘democratic’ or legitimizing, media criticism requires an explicit argumentation of why the medium or the journalistic product is being criticized. Accusations of failure necessitate an articulation of the associated standards that are not met (Carey, Citation1974; Carlson, Citation2017). Moreover, some scholars argue that this criticism needs to be expressed in an unemotional language (Carey, Citation1974). Only then, ‘criticism is not the mark of failure and irrelevance [but] the sign of vigor and importance’ (Carey, Citation1974, p. 240), maintaining the legitimacy of journalism as an integral part of democracy. Importantly, journalists also prefer civil and substantiated criticism (Cheruiyot, Citation2018). Consequently, this criticism has a greater potential to affect change in journalism.

However, this is not the rule for how most media criticism is expressed in current political discourse. Rather, media criticism is increasingly combative, with critics attacking the media to implement changes in reporting (Carlson, Citation2017). Criticism by politicians is increasingly characterized by hostility and incivility (e.g. Krämer, Citation2018; Tong, Citation2018; RSF, Citation2018), and incidents of humiliation and intimidation by public authorities are on the rise (Clark & Grech, Citation2017). While political leaders have regularly and openly criticized the media for decades – a prominent example is Richard Nixon – the intensity of antagonism that is expressed by politicians today is unprecedented (Carlson, Citation2018; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Citation2018).

In particular, the labels ‘fake news’ and ‘lying press’ are inherently uncivil, as lying accusations are considered a form of incivility (Coe, Kenski, & Rains, Citation2014). The major purpose of incivility is to discourage others from ‘frankly expressing their opinions and thus to obstruct an open and productive debate’ (Prochazka, Weber, & Schweiger, Citation2018, p. 66). Therefore, criticism that is expressed in an emotional and uncivil language does not strive for constructively evaluating media quality in terms of its democratic value. Instead, it can be seen as an attempt to delegitimize the opponent (Chilton, Citation2004).

Furthermore, political criticism is often expressed without argumentation on what grounds the critique is built on. Politicians particularly use media criticism as a strategy when confronted with negative coverage of their persona or actions (Brants, de Vreese, Möller, & van Praag, Citation2010; Smith, Citation2010). In the same vein, political actors currently attack critical news media with the terms ‘fake news’ and ‘lying press’, without substantiating why a medium is ‘fake’ or ‘lying’. However, ‘attack is not criticism’ (Carey, Citation1974, p. 235), and charges of inadequacy always necessitate a clear description of ‘a corresponding ideal that is not being met’ (Carlson, Citation2017, p. 165).

Consequently, the nature of the current criticism predominantly deviates from legitimizing or democratic criticism as described above, as it is often expressed in an emotional, uncivil language and without argumentation. Its purpose is not to critically evaluate the quality of journalism to preserve it; rather, its purpose is to attack journalism’s legitimacy. Thus, we term this type of expression of disapproval as delegitimizing media criticism and identify the fake news label (as well as lying press accusations in German-speaking countries) as its currently most prominent manifestation.

Where does the fake news label come from?

We can trace the weaponization of the fake news label back to the emergence of digital media and changes in the political architecture of modern media democracies. In today’s fragmented and digital media environment, journalists and other information producers are competing over the public’s attention, and the criticism of the mainstream media and professional journalism as perhaps outdated and disconnected elitist ivory towers by alternative media, bloggers, and citizens seems increasingly common (e.g. Carlson, Citation2009; Craft, Vos, & Wolfgang, Citation2016; Figenschou & Ihlebæk, Citation2018; Vos, Craft, & Ashley, Citation2012). This mechanism is strengthened by information flows on social media platforms, where news stories are increasingly shared alongside critical commentary on the performance of the media (Carlson, Citation2016). On these platforms, citizens have become aware of how easy it is to manipulate information. Realizing this potential of manipulation has likely supported public assumptions that journalists are also using deceptive techniques of information manipulation online (Neverla, Citation2017).

Furthermore, the rise of social media also means that politicians can now circumvent journalistic gatekeeping and talk directly to the public, and they are no longer checked for their use of media criticism as a means of gathering voter support (Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017; Tong, Citation2018). Media criticism is particularly popular within a rising type of populist parties in democracies (e.g. McNair, Citation2017; Tambini, Citation2017). Modern populist communication strategies are indeed characterized by an anti-elitism directed at the media, and such modern populists have rendered growing media criticism and anti-media discourse a fixed feature of their rhetoric for years now (De Vreese, Citation2017; Jagers & Walgrave, Citation2007). Calling the media ‘fake news’ can thus be seen as yet another characteristic element of populist political communication, indicating the news media as being ‘pro-elite’ and undermining opposition and journalism’s role as the fourth estate (Krämer, Citation2018; McNair, Citation2017; Tambini, Citation2017). In recent years, studies have shown that populist media criticism is growing (Engesser et al., Citation2017; Figenschou & Ihlebæk, Citation2018; Holt & Haller, Citation2017) and now ‘belongs to the standard repertoire of populist parties’ (Esser, Stępińska, & Hopmann, Citation2016, p. 376).

Further connected with the rise of populism and the crisis of journalism is an increasing depreciation of ‘elites’, in general (McNair, Citation2017), and those who are commissioned with the provision of factual information (i.e. scientists and politicians), specifically (e.g. Mooney & Kirshenbaum, Citation2010; Van Aelst et al., Citation2017). Additionally, increasing levels of political polarization in many democracies seem to promote a mainstream climate of opinion that is characterized by few shared facts and disrespect for other worldviews. Such polarization can be connected to what has been termed an ‘increasing relativism of facts’ or ‘post-truth politics’, a trend in political communication where factual evidence is seen as less important than personal opinion, with public actors increasingly denying factual information (Van Aelst et al., Citation2017). Using the term ‘fake news’ is one form of this worrying trend. In doing so, the basic ground rules of political decision-making are changed by moving beyond the ‘cliché that all politicians lie and make promises they have no intention of keeping – this still expects honesty to be the default position. In a post-truth world, this expectation no longer holds’ (Higgins, Citation2016, p. 9).

In summary, the news media is afflicted by a culture of permanent criticism in a digitalized political discourse and a new class of populist politicians, who attack journalists at a time when they are economically and socially vulnerable. Anti-elitist tendencies in many Western democracies have made way for public doubts as to the performance of the fundamental institutions that uphold these democracies, such as science, politics and journalism. The use of the fake news label is a further symptom of this affliction.

Empirical evidence on the fake news label

The fake news label has been considered by only a few studies thus far. Lischka (Citation2019) analyses how The New York Times (NYT) reports on fake news accusations by Donald Trump and finds that the newspaper understands those accusations as an attack on their journalistic legitimacy. While there are attempts to defend journalism’s legitimacy in general, the NYT misses the chance to explicitly defend its own legitimacy. Similarly, Denner and Peter (Citation2017) analyse how German newspapers reflect on the lying press allegations and find that outlets fail to elaborate on these attacks and do not sufficiently demonstrate the media’s democratic importance. Moreover, in some cases, journalists even apply the term to ironically describe themselves.

In regard to effects, the research seems to suggest that exposure to elite discourse about fake news has the potential to decrease citizens’ trust in news media (Van Duyn & Collier, Citation2019). Moreover, a fake news attack by President Trump has no effect on respondents who disapprove of Trump but significantly reduces perceived media accuracy and media trust for Trump supporters (Guess et al., Citation2017).

Therefore, while there is growing concern, we see that there is a dearth of studies on the label. However, the few studies focusing on that side show that fake news is not only about an increase in false information but also about a crisis of how the news media is perceived. Such studies also show that the fake news label potentially influences citizens’ levels of media trust. While some journalists seem to be aware of that dimension of the fake news phenomenon, they mostly fail to distance themselves from such allegations and to defend their legitimacy.

Research agenda

Studying fake news is truly about understanding two distinctive phenomena: first, it is about an increase in disinformation that appears in journalistic format, and second, it is about an instrumentalization of the term and its inherent negative connotation to delegitimize news media. Consequently, these two dimensions have distinct consequences and require different scientific approaches.

The fake news genre

First, as shown above, the empirical research on fake news is heavily focused on U.S. media and politics, with some exceptions from Western Europe. However, as a recent poll shows, exposure to fake news stories is likely prevalent in Eastern European countries such as Hungary and Turkey (Newman et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, fake news is widely discussed in many other parts of the world, such as South Africa (Wasserman, Citation2017) and India (Bhaskaran, Mishra, & Nair, Citation2017). Importantly, Wasserman (Citation2017, p. 3) argues, ‘News – whether “fake” or “real” – should not be understood outside of its particular contexts of production and consumption’. Indeed, journalism differs around the globe. For example, studies show that there are differences in journalists’ approaches to ethical principles and the way they understand their social function between Western contexts and developing or authoritarian contexts (e.g. Hanitzsch et al., Citation2011). Similarly, fake news might constitute different problems within different country contexts as well. For instance, in India, a larger problem than citizens falling for fake news articles online is that journalists increasingly cover the false information propagated by political actors (Bhaskaran et al., Citation2017). These examples quite simply point to the need to investigate the fake news genre both in specific country case studies and in a cross-national comparative manner outside of the Western contexts, in general, and the U.S. context, specifically.

Second, future studies must shed light on how exactly journalistic characteristics and instruments are used to produce fake news. Along these lines, we do not know who was behind the creation of many fake news websites during past election campaigns or in routine periods and what their motivations were. Here, systematic and large-scale content analyses of fake news websites are needed. The partisan media might play a role in the dissemination of fake news; however, this link remains speculative (e.g. Vargo et al., Citation2018). Research on the actual reach of fake news is also both limited to and heavily focused on the U.S. (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Guess et al., Citation2018; Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018), with the exception of one study considering fake news in France and Italy (Fletcher et al., Citation2018).

Third, most studies focus on content and reach of fake news, neglecting its possible effects. As we conceptualize fake news as a form of disinformation, it likely leads to misperceptions with politically relevant consequences (Lazer et al., Citation2017). Misperceptions are easily formed, often after first exposure (Cook, Ecker, & Lewandowsky, Citation2015). If disinformation is perceived to be a result of journalistic practice, citizens might evaluate content less critically. Consequently, future studies must not merely test whether citizens perceive fake news to be real but, more importantly, whether presenting disinformation in a pseudojournalistic manner actually leads to different or even stronger misperceptions than false information that appears in non-journalistic formats. Furthermore, it has been shown that political mis- and disinformation continuously affect attitudes even after they have been corrected (Thorson, Citation2016). A possible explanation for this is that invalidated pieces of information stay accessible in memory and thus are still available when citizens try to explain unfolding events (Cook et al., Citation2015). In that way, even fake news articles that have been disputed by fact-checkers might result in political misperceptions. These ideas, as well as the longevity of such effects (Lecheler & de Vreese, Citation2016), are in need of investigation. An important next step would be to test how misperceptions stemming from fake news might affect political behaviour in the long run (Lazer et al., Citation2018). In addition, it has been suggested that fake news is targeted at emotions (Bakir & McStay, Citation2018). This suggestion first requires quantitative empirical testing. Then, in line with the research focusing on the psychological processes that explain news effects (e.g. Lecheler, Schuck, & De Vreese, Citation2013), studies might test if the fake news effects on misperceptions are made possible through cognitive and affective processing.

Research on the computer-assisted detection of fake news and disinformation in general is essential but could also be paired with research on enhancing media literacy in the digital information environment for citizens directly (McNair, Citation2017; Tandoc et al., Citation2018). We also suggest that existing approaches to enhance media literacy, such as Facebook’s guide, ‘Tips how to spot false news’ (e.g. Thomas, Citation2017), need to be evaluated.

These suggested avenues for future research refer to content that assuredly meets all three fake news characteristics. However, as stated above, the intentionality of fake news production – as a distinguishing characteristic – is difficult to study. Thus, research methods are required that can capture malicious intent in news production. As already mentioned, investigating outlets’ coverage over time and tracking if they publish errata about inaccurate reports might be a first step. Another possibility might lie in reconstructive interviews, which aim to identify the processes of how journalists create news stories (Hoxha & Hanitzsch, Citation2018). Applying this method might identify fake news from sources such as alternative media outlets, partisan media outlets, and mainstream media outlets. We see a great need for research on the effects of not only intentionally but also unintentionally created false news from these outlets, as well-known outlets have a much larger readership (e.g. Fletcher et al., Citation2018) and probably enjoy higher levels of perceived credibility (e.g. Flanagin & Metzger, Citation2007). Consequently, mis- and disinformation presented in these formats are likely to lead to stronger misperceptions compared to information stemming from fake news sites. However, this research should not be undertaken under the name of fake news until it is proven that the content meets all three fake news characteristics.

The fake news label

The crucial areas for research on the label cover (a) the general nature of the application of the fake news label, (b) how journalism is affected by and reacts to such a label, and (c) what it entails for citizens.

First, we urgently need more empirical evidence on the occurrence of the fake news label, for example, whether it is predominantly applied to single news articles and media outlets or generalized to ‘the media’, to weaken it as a pillar of democracy. In this context, we want to stress again that the fake news label is only the most visible symptom of public attacks on journalistic legitimacy. We have also discussed the ‘lying press’ accusations in this context, but we lack knowledge on what attempts to delegitimize news and journalism look like beyond these prominent buzzwords. Additionally, it is suggested that these journalism-delegitimizing attempts have been increasing in recent years, an assumption that requires descriptive analyses over time. Furthermore, while there are first hints that the fake news label is a global phenomenon, future research needs to investigate to what extent the label and related attacks are actually employed by political actors other than U.S. president Donald Trump and whether the idea that populist politics are its main driver truly holds across case studies and countries.

Moreover, there is an urgent need for more research on how journalism responds to those attacks on its legitimacy. In times where ‘skepticism has become the culturally accepted perspective when confronted with questions about believing the news’ (Carlson, Citation2017, p. 178), it is crucial that journalists not only actively distance themselves from delegitimizing attacks but also accept and react to constructive criticism. While there are content analyses on the reactions of a few outlets (Denner & Peter, Citation2017; Lischka, Citation2019), we need a broader picture. Furthermore, we see a crucial need for research with journalists: are journalists aware of the instrumentalization, and can information about this prevent them from using these terms so often and – importantly – against themselves? Moreover, as Lischka (Citation2019) notices, there is a need to experimentally test how convincing readers find newspapers’ reactions to those attacks and which relegitimization strategies are effective. Additionally, it remains an open question if news outlets (especially partisan and alternative media) themselves participate in attempts to delegitimize (other) news media. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, it is important to understand how the inherent hostility of the fake news label and other delegitimizing strategies affect journalists and their work practices, for example, in terms of self-censorship.

We further suggest that studies test whether the fake news label and related journalism-delegitimizing attacks by politicians have an impact on how citizens perceive the media. As elite rhetoric is a powerful factor influencing the formation of opinion, political elite attacks on the media have an impact on how citizens perceive such media (Ladd, Citation2012). When used by political elites, the fake news label – as well as other delegitimizing attacks – might consequently affect citizens’ media perceptions. As shown above, an experiment provides the first indications that the fake news label, applied by U.S. President Trump, decreases the media trust of Trump supporters (Guess et al., Citation2017). Thus, it can be assumed that the effectiveness of the label depends on the shared political ideology with the source it is coming from (see also Swire, Berinsky, Lewandowsky, & Ecker, Citation2017). Interestingly, in this context, The New York Times, for example, claims that since President Trump’s fake news accusation, there actually has been an increase in subscriptions to the newspaper (Chapman, Citation2017). Therefore, a further possibility is that the fake news label does not reduce but actually increases media trust, especially for citizens who do not support Donald Trump. For those reasons, the fake news label may even backfire and reduce the credibility of the political actor using it. Thus, research is needed to test whether the effect found by Guess et al. (Citation2017) holds when the fake news label or other attacks on journalism’s legitimacy come from other politicians. Furthermore, studies need to investigate the fake news label’s impact on media perceptions outside of the U.S., as concern about the usage of the term fake news is growing around the world, even more so in Austria (56%) and Bulgaria (53%) than in the U.S. (48%) (Newman et al., Citation2018, pp. 37–38).

Moreover, we need a test of the possible moderating and mediating factors of such effects, as they will likely depend on citizens’ general political trust (e.g. Hanitzsch et al., Citation2018) and emotions (e.g. Wirz, Citation2018). This test will allow for the development of a comprehensive model of the effects of the fake news label. Finally, while a first qualitative study indicates that citizens are aware of the instrumentalization of the term (Nielsen & Graves, Citation2017), we lack quantitative studies confirming this finding, as well as how being aware of such instrumentalization affects the label’s impact on media perceptions.

Considering both the label and the genre, we suggest that there should be a focus on counteracting detrimental effects. First, there may be more effective ways to reduce misperceptions, in general, and to weaken the effects of the fake news genre, in particular. For instance, providing a correction from a source with shared political ideology might reduce misperceptions (see also Lazer et al., Citation2017). Second, as noted by several scholars, one of the currently most pressing questions is how trust in news media can be reinforced (e.g. McNair, Citation2017; Nelson & Taneja, Citation2018). Here, a possibility could be to test how politicians’ statements concerning media outlets’ credibility might increase levels of trust in these outlets for citizens who support these politicians. Furthermore, future research should investigate whether ‘constructive journalism’ – an innovative approach where journalists deviate from focusing on negative and conflict news (McIntyre & Gyldensted, Citation2017) – has a positive effect on media trust.

Concluding remarks

The excessive use of the term fake news in public discourse has driven a number of scholars and public officials to suggest that it should be retired (HLEG, Citation2018; House of Commons, Citation2018; Sullivan, Citation2017; Wardle & Derakhshan, Citation2017). While we agree with the concerns regarding the term, considering its prominence and large range, this retirement might not be within the limits of scholarly influence. This paper aims to calm troubled water by providing a concise review and systematization of the available empirical and theoretical literature on this phenomenon to clarify what it actually means for political communication environments. We suggest that fake news is a two-dimensional phenomenon: there is the fake news genre, relating to the intentional creation of pseudojournalistic disinformation, and there is the fake news label, describing the political instrumentalization of the term by political actors to delegitimize journalism and news media.

Neither dimension is likely to completely disappear; thus, a distinction may at least help to classify different trends in modern political communication for future research. The fake news genre is probably the most visible symptom of an increase in disinformation in the online information environment. Fake news potentially leads to misperceptions and contributes to ‘growing inequalities in political knowledge’, one of the most pressing challenges for democracy today (Van Aelst et al., Citation2017, p. 19). The use of the term as a label to ensure delegitimizing media criticism possibly affects how citizens perceive journalism in terms of accuracy and credibility. This effect matters because media perceptions shape citizens’ use of news media and how they are affected by such media (Tsfati, Citation2014). The use of the term as a label might thus ‘driv[e] audiences away to other news sources’ and contribute to political polarization (Carlson, Citation2017, p. 179) – yet another crucial challenge for democracy (Van Aelst et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, the label applied against accurate news coverage relates to ‘increasing relativism of facts’ (Van Aelst et al., Citation2017). In that context, the fake news label might spread to science: a recently emerged debate about ‘predatory publishers’ is employing the hashtag ‘#FakeScience’ (Heller, Citation2018). If this term gains comparable attention to that of fake news, it might soon be turned and used to label honest and institutionally supported scientific studies as ‘fake science’.

Our review of the literature shows that both dimensions of fake news are damaging to journalism as a whole. Because it is dangerous, we want to conclude this review by urging scholars to use the term more carefully in their own work going forward. First, the term should not be applied to any unverified journalistic products. Inaccurate news for which it cannot be determined if it was created deliberately could thus simply be called ‘false news’. Furthermore, scholars should think twice about how necessary the term is when analysing mis- and disinformation in general. In line with several other authors (HLEG, Citation2018; Wardle & Derakhshan, Citation2017), we argue that the term fake news is not applicable to capture all phenomena of falsehood in the news environment. This term describes two very specific instances of a crisis in democracy and must not be normalized to a much wider discourse.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Sophie Lecheler http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7320-1012

Notes

1. E.g. with the help of new audio and video manipulation tools: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jul/26/fake-news-obama-video-trump-face2face-doctored-content.

2. These are two of the fake news websites that spread misinformation related to the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Silverman, Citation2016).

3. However, this requires the source of news parody to reveal that its content is meant to be understood humorously. For example, The Onion states on its website that satire and parody are ‘a form of free speech and expression’ (https://www.theonion.com/about).

4. Of course, limiting the usage of the term fake news does not mean that content that does not meet all three characteristics is harmless. False information of any kind can of course have detrimental consequences. Our objective, however, is to limit the use of the term fake news to lessen its power as a political instrument (i.e. fake news label).

5. i.e. software-controlled social media accounts that automatically interact with other users (e.g., Howard et al., Citation2017).

References

- Albright, J. (2017). Welcome to the era of fake news. Media and Communication, 5(2), 87–89.

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236.

- Bakir, V., & McStay, A. (2018). Fake news and the economy of emotions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 154–175.

- Bale, J. M. (2007). Political realism: On distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics. Patterns of Prejudice, 41(1), 45–60.

- Baym, G. (2005). The daily show: Discursive integration and the reinvention of political journalism. Political Communication, 22(3), 259–276.

- Berinsky, A. J. (2017). Rumors and health care reform: Experiments in political misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241–262.

- Bhaskaran, H., Mishra, H., & Nair, P. (2017). Contextualizing fake news in post-truth era: Journalism education in India. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 27(1), 41–50.

- Borden, S. L., & Tew, C. (2007). The role of journalist and the performance of journalism: Ethical lessons from “fake” news (seriously). Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 22(4), 300–314.

- Brants, K., de Vreese, C., Möller, J., & van Praag, P. (2010). The real spiral of cynicism? Symbiosis and mistrust between politicians and journalists. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 15(1), 25–40.

- Brennen, B. (2017). Making sense of lies, deceptive propaganda, and fake news. Journal of Media Ethics, 32(3), 179–181.

- Carey, J. W. (1974). Journalism and criticism: The case of an undeveloped profession. The Review of Politics, 36(2), 227–249.

- Carlson, M. (2009). Media criticism as competitive discourse: Defining reportage of the Abu Ghraib scandal. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 33(3), 258–277.

- Carlson, M. (2015). Introduction: The many relationships of journalism. In M. Carlson & S. C. Lewis (Eds.), Boundaries of journalism: Professionalism, practices and participation (pp. 1–26). London: Routledge.

- Carlson, M. (2016). Embedded links, embedded meanings: Social media commentary and news sharing as mundane media criticism. Journalism Studies, 17(7), 915–924.

- Carlson, M. (2017). Journalistic authority: Legitimating news in the digital era. New York City: Columbia University Press.

- Carlson, M. (2018). The information politics of journalism in a post-truth age. Journalism Studies, 19(13), 1879–1888.

- Chapman, B. (2017, February). Donald Trump’s “fake news” attacks on New York Times have sent its subscriptions ‘through the roof”. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/donald-trump-attacks-new-york-times-increase-subscriptions-fake-news-a7602656.html

- Cheruiyot, D. (2018). Popular criticism that matters: Journalists’ perspectives of “quality” media critique. Journalism Practice, 12(8), 1008–1018.

- Chilton, P. (2004). Analysing political discourse: Theory and practice. London: Routledge.

- Clark, M., & Grech, A. (2017). Unwarranted interference, fear and self-censorship among journalists in Council of Europe Member States. In U. Carlsson & R. Pöyhtäri (Eds.), The assault on journalism. Building knowledge to protect freedom of expression (pp. 221–226). Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658–679.

- Cook, J., Ecker, U., & Lewandowsky, S. (2015). Misinformation and how to correct it. In R. Scott & S. Kosslyn (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences: An interdisciplinary, searchable, and linkable resource (pp. 1–17). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Craft, S., Vos, T. P., & Wolfgang, D. J. (2016). Reader comments as press criticism: Implications for the journalistic field. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, 17(6), 677–693.

- Denner, N., & Peter, C. (2017). Der Begriff Lügenpresse in deutschen Tageszeitungen. [The term lying press in German newspapers]. Publizistik, 62(3), 273–297.

- De Vreese, C. H. (2017). Political journalism in a populist age (Policy Paper). Retrieved from https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Political-Journalism-in-a-Populist-Age.pdf?x78124

- DiFranzo, D., & Gloria-Garcia, K. (2017). Filter bubbles and fake news. ACM Crossroads, 23(3), 32–35.

- Douglas, K., Ang, C. S., & Deravi, F. (2017). Farewell to truth? Conspiracy theories and fake news on social media. The Psychologist, 30, 36–42.

- Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., & Büchel, F. (2017). Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society, 20(8), 1109–1126.

- Esser, F., Stępińska, A., & Hopmann, D. (2016). Populism and the media. Cross-national findings and perspectives. In T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Stromback, & C. De Vreese (Eds.), Populist political communication in Europe (pp. 365–380). New York: Routledge.

- Figenschou, T. U., & Ihlebæk, K. A. (2018). Challenging journalistic authority: Media criticism in far-right alternative media. Journalism Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1500868

- Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. J. (2007). The role of site features, user attributes, and information verification behaviors on the perceived credibility of web-based information. New Media and Society, 9(2), 319–342.

- Fletcher, R., Cornia, A., Graves, L., & Nielsen, R. K. (2018). Measuring the reach of “fake news” and online disinformation in Europe. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-01/Measuring the reach of fake news and online disinformation in Europe FINAL.pdf

- Flynn, D. J., Reifler, J., & Nyhan, B. (2017). The nature and origins of misperceptions: Understanding false and unsupported beliefs about politics. Political Psychology, 38(S1), 127–150.

- George, C. (2018). Journalism, censorship, and press freedom. In T. Vos (Ed.), Journalism (pp. 473–491). Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

- Gottfried, J., Stocking, G., & Grieco, E. (2018). Democrats and republicans Remain split on support for news media’s watchdog role. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2018/09/25/democrats-and-republicans-remain-split-on-support-for-news-medias-watchdog-role/

- Guess, A., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2017). “You’re fake news!” The 2017 poynter media trust survey. Retrieved from https://poyntercdn.blob.core.windows.net/files/PoynterMediaTrustSurvey2017.pdf

- Guess, A., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Selective exposure to misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 U. S. presidential campaign. Retrieved from https://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/fake-news-2016.pdf

- Hanitzsch, T., Hanusch, F., Mellado, C., Anikina, M., Berganza, R., Cangoz, I., … Kee Wang Yuen, E. (2011). Mapping journalism cultures across nations: A comparative study of 18 countries. Journalism Studies, 12(3), 273–293.

- Hanitzsch, T., Van Dalen, A., & Steindl, N. (2018). Caught in the nexus: A comparative and longitudinal analysis of public trust in the press. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 3–23.

- Heller, L. (2018). Beyond #FakeScience: How to overcome shallow certainty in scholarly communication. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2018/08/02/beyond-fakescience-how-to-overcome-shallow-certainty-in-scholarly-communication/

- Higgins, K. (2016). Post-truth: A guide for the perplexed. If politicians can lie without condemnation, what are scientists to do? Nature, 540, 9–9.

- HLEG. (2018). A multi-dimensional approach to disinformation. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation

- Holt, K., & Haller, A. (2017). What does ‘Lügenpresse’ mean? Expressions of media distrust on PEGIDA’s Facebook pages. Politik, 20(4), 42–57.

- Horne, B. D., & Adalı, S. (2017). This just in : Fake news packs a lot in title, uses simpler, repetitive content in text body, more similar to satire than real news. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.09398

- House of Commons. (2018). Disinformation and ‘fake news’: Interim report. Fifth Report of Session 2017–19. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/digital-culture-media-and-sport-committee/inquiries/parliament-2017/fake-news-17-19/

- Howard, P. N., Bolsover, G., Bradshaw, S., Kollanyi, B., & Neudert, L.-M. (2017). Junk news and bots during the U.S. Election: What were michigan voters sharing over twitter? Retrieved from http://275rzy1ul4252pt1hv2dqyuf.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2206.pdf

- Hoxha, A., & Hanitzsch, T. (2018). How conflict news comes into being: Reconstructing ‘reality’through telling stories. Media, War & Conflict, 11(1), 46–64.

- Humprecht, E. (2018). Where ‘fake news’ flourishes: A comparison across four Western democracies. Information, Communication & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1474241

- Jagers, J., & Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research, 46(3), 319–345.

- Jowett, G. S., & O’Donnell, V. (2014). Propaganda and persuasion (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Khaldarova, I., & Pantti, M. (2016). Fake news. Journalism Practice, 10(7), 891–901.

- Krämer, B. (2018). How journalism responds to right-wing populist criticism. In K. Otto & A. Köhler (Eds.), Trust in media and journalism (pp. 137–154). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Ladd, J. (2012). Why Americans hate the media and how it matters. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lazer, D., Baum, M., Benkler, J., Berinsky, A., Greenhill, K., Metzger, M., … Zittrain, J. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096.

- Lazer, D., Baum, M., Grinberg, N., Friedland, L., Joseph, K., Hobbs, W., & Mattsson, C. (2017, May). Combating fake news: An agenda for research and action drawn from presentations by. Retrieved from https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Combating-Fake-News-Agenda-for-Research-1.pdf

- Lecheler, S., & de Vreese, C. H. (2016). How long do news framing effects last? A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Annals of the International Communication Association, 40(1), 3–30.

- Lecheler, S., & Kruikemeier, S. (2016). Re-evaluating journalistic routines in a digital age: A review of research on the use of online sources. New Media & Society, 18(1), 156–171.

- Lecheler, S., Schuck, A., & De Vreese, C. (2013). Dealing with feelings: Positive and negative discrete emotions as mediators of news framing effects. Communications - The European Journal of Communication Research, 38(2), 189–209.

- Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die. New York: Crown.

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369.

- Lischka, J. A. (2019). A badge of honor? Journalism Studies, 20(2), 287–304.

- Löfgren Nilsson, M., & Örnebring, H. (2016). Journalism under threat: Intimidation and harassment of Swedish journalists. Journalism Practice, 10(7), 880–890.

- Matthes, J., Maurer, P., & Arendt, F. (2019). Consequences of politicians’ perceptions of the news media: A hostile media phenomenon approach. Journalism Studies, 20(3), 345–363.

- McIntyre, K., & Gyldensted, C. (2017). Constructive journalism: An introduction and practical guide for applying positive psychology techniques to news production. The Journal of Media Innovations, 4(2), 20–34.

- McNair, B. (2017). Fake news: Falsehood, fabrication and fantasy in journalism. New York: Routledge.

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., Eyal, K., Lemus, D. R., & Mccann, R. M. (2003). Credibility for the 21st century: Integrating perspectives on source, message, and media credibility in the contemporary media environment. Annals of the International Communication Association, 27(1), 293–335.

- Mihailidis, P., & Viotty, S. (2017). Spreadable spectacle in digital culture. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(4), 441–454.

- Mitchell, A., Barthel, M., & Holcomb, J. (2016). Many Americans believe fake news is sowing confusion. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-is-sowing-confusion/

- Mitchell, A., Matsa, K. E., Shearer, E., Simmons, K., Silver, K., Johnson, C., … Taylor, K. (2018). Populist views, more than left-right identity, play a role in opinions of the news media in Western Europe. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2018/05/14/populist-views-more-than-left-right-identity-play-a-role-in-opinions-of-the-news-media-in-western-europe/#table

- Mooney, C., & Kirshenbaum, S. (2010). Unscientific America: How scientific illiteracy threatens our future. New York: Basic Books.

- Möseneder, M. (2018, September). Innenministerium beschränkt Infos für ‘kritische Medien’ [Interior minister restricts information for ‘critical’ media]. Der Standard. Retrieved from https://derstandard.at/2000087988184/Innenministerium-beschraenkt-Infos-fuer-kritische-Medien

- Mustafaraj, E., & Metaxas, P. T. (2017). The fake news spreading plague: Was it preventable? Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1703.06988

- Nelson, J. L., & Taneja, H. (2018). The small, disloyal fake news audience: The role of audience availability in fake news consumption. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3720–3737.

- Neudert, L. M. N. (2017). Computational propaganda in Germany: A cautionary tale. Retrieved from http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/06/Germany_LMNeditv3.pdf

- Neverla, I. (2017). “Lügenpresse” – Begriff ohne jede Vernunft? Eine alte Kampfvokabel in der digitalen Mediengesellschaft [Lying press - Term without any reason? An old battle cry in the digital media environment]. In V. Lilienthal & I. Neverla (Eds.), Lügenpresse [Lying press] (pp. 18–44). Cologne: Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A. L., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Reuters institute digital news report 2017. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20web_0.pdf

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A. L., & Nielsen, R. K. (2018). Reuters institute digital news report 2018. Retrieved from media.digitalnewsreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/digital-news-report-2018.pdf?x89475.

- Nielsen, R. K., & Graves, L. (2017). “News you don’t believe”: Audience perspectives on fake news. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2017-10/Nielsen%26Graves_factsheet_1710v3_FINAL_download.pdf

- Oxford Dictionaries. (2019). Fake. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/fake