ABSTRACT

Rising political polarization is, in part, attributed to the fragmentation of news media and the spread of misinformation on social media. Previous reviews have yet to assess the full breadth of research on media and polarization. We systematically examine 94 articles (121 studies) that assess the role of (social) media in shaping political polarization. Using quantitative and qualitative approaches, we find an increase in research over the past 10 years and consistently find that pro-attitudinal media exacerbates polarization. We find a hyperfocus on analyses of Twitter and American samples and a lack of research exploring ways (social) media can depolarize. Additionally, we find ideological and affective polarization are not clearly defined, nor consistently measured. Recommendations for future research are provided.

The role of (social) media in political polarization: a systematic review

Political polarization is on the rise not only in the United States (Arceneaux et al., Citation2013; see also Abramowitz & Saunders, Citation2008; Pew Research Center, Citation2017), but also across the world (Gidron et al., Citation2019). Today political elites (Heaney et al., Citation2012), elected officials (Hare & Poole, Citation2014), and everyday people (Frimer et al., Citation2017) are polarized.Footnote1 There are two distinct forms of political polarization. The first is ideological polarization, which is the divergence of political opinions, beliefs, attitudes, and stances of political adversaries (Dalton, Citation1987). The second is affective polarization, which is based on work considering the role of identity in politics (Mason, Citation2018), and how identity salience within groups (e.g. political parties) can exacerbate out-group animosity (e.g. Gaertner et al., Citation1993; Iyengar et al., Citation2012). Affective polarization assesses the extent to which people like (or feel warmth towards) their political allies and dislike (or feel lack of warmth towards) their political opponents (Iyengar et al., Citation2012).

Higher levels of polarization can be beneficial for society – predicting higher levels of political participation, and perceptions of electoral choice (Wagner, Citation2021). However, political polarization can also be bad for democracy, increasing the centralization of power (Lee, Citation2015), congressional gridlock (Jones, Citation2001), and making citizens less satisfied (Wagner, Citation2021). Previous work has also highlighted interpersonal implications of polarization, including an unwillingness to interact with (Frimer et al.,Citation2017), and dehumanization towards (Mason, Citation2018) political adversaries.

Given that people are unwilling to engage in day-to-day interactions with their political adversaries, many build their impressions of opponents via the media – meaning (social) media is increasingly shaping how we perceive the political environment. As media has become more fragmentated (Van Aelst et al., Citation2017) and partisan (DellaVigna & Kaplan, Citation2007), people have become more polarized both ideologically (Jones, Citation2002) and affectively (Lau et al., Citation2017). However, media may not always have a polarizing effect on viewers. Some suggest social media (Valenzuela et al., Citation2019) and traditional media (Udani et al., Citation2018) have no effect on political polarization. While others suggest in certain circumstances, political information can actually have a depolarizing effect on viewers (Beam et al., Citation2018; Kubin et al., Citation2021; Wojcieszak et al., Citation2020). These mixed results highlight our understanding of when and why media exacerbates polarization is murky, pointing to the need for assessment of the literature.

Scholars have reviewed the role of media and political polarization; however, some key gaps remain unanswered. For example, Prior’s Citation2013 review provides a persuasive perspective on the ways in which media can influence political polarization – suggesting the media may not significantly influence the average persons’ polarization. However, this review fails to make a distinction between affective and ideological polarization, rather grouping both into the overarching umbrella of ‘political polarization.’ Further, the political climate has drastically changed in the U.S. since this review, with greater polarization (Pew Research Center, Citation2017), increased social media use (Pew Research Center, Citation2019), more partisan news (Jurkowitz et al., Citation2020), and growing animosity between political opponents (Finkel et al., Citation2020). Finally, the review solely examined the effect of media on political polarization in the U.S. context, ignoring research from across the world (e.g. Chile (Valenzuela et al., Citation2019), Germany (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Citation2015), and Ghana (Conroy-Krutz & Moehler, Citation2015)).

A more recent review provides an informative assessment of the role of media on political polarization and addresses several gaps not addressed in Prior’s review (Tucker et al., Citation2018). The authors distinguish between ideological and affective polarization and consider polarization outside of the American context. However, this review only focused on the role of social media in political polarization – thus not considering the well-documented polarizing effects of news media (e.g. McLaughlin, Citation2018).

While past reviews provide meaningful insights into the ways in which media shapes polarization, key questions remain unanswered. In our systematic review of the literature, we wish to close these research gaps and answer three central research questions. Our first research question (RQ1) is quantitatively oriented and asks: How can the current state of research on media and political polarization be characterized regarding (a) the development of the field over time, and (b) the country of samples? Our second research question (RQ2) is qualitatively orientated and asks: What do we know about media and political polarization in regard to (a) media contents (e.g. is media coverage increasingly polarized?), (b) media exposure (e.g. do news consumers increasingly use politically polarized media contents?), and (c) media effects (e.g. how can certain types of media exacerbate (or inhibit) political polarization?)? The third research question (RQ3) is both quantitatively and qualitatively oriented and asks: How is polarization discussed and examined in the literature?

In the present study, we employed a content-based analytical approach (e.g. Ahmed & Matthes, Citation2017). We conducted a systematic and extensive search of the literature and identified a total of 94 articles (121 studies) on media and polarization. Then we used a quantitative approach and examined various dimensions including time of publication, country samples come from, and type of polarization examined.Footnote2 We also employed a qualitative approach, reviewing all studies in depth in order to identify the common themes and key findings. Taken together, our study provides insights and new perspectives on the role of media in political polarization. Furthermore, it fills persisting research gaps in the literature and offers new avenues for future research.

Methodology

Study retrieval

The goal of the current research was to examine all research articles relevant to the role of (social) media in political polarization. We theorized that researchers from various fields (e.g. political communication, political science, and psychology) have examined this topic. Due to this interdisciplinary interest, we conducted a systematic search on Web of Science – aligned with previous reviews (Ahmed & Matthes, Citation2017; Tsfati et al., Citation2020; von Sikorski, Citation2018), as it provides access to multiple interdisciplinary databases, and is the leading science search platform in the world (Li et al., Citation2018).

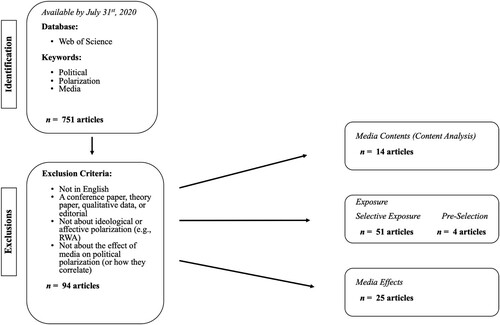

For our search we entered three keywords: ‘Political,’ ‘Polarization,’Footnote3 and ‘Media.’ Since we began this search at the beginning of August 2020, we set the search parameters to only access papers that were available as of 31 July 2020Footnote4 or earlier and we limited our search to articles published in English. Our search produced 751 articles, see .

Study selection process

Selection for articles was based on two inclusion criterium; (1) articles had to be peer reviewed and quantitative, (2) articles had to be specifically focused on ideological or affective polarization and the main focus of the paper had to be on how media shapes (or relates to) political polarization. Papers whose main research question, or primary analysis, was based on how media relates to political polarization were deemed as having a main focus on this topic. With this inclusion criteria, we gathered 94 articles (121 studies) for our analyses ().

After coding all studies, we examined the studies both quantitatively and qualitatively. For our qualitative analyses, we split all articles into three categories for understanding the role of media in political polarization – (1) media contents (n = 14), (2) media exposure (n = 55), (3) media effects (n = 25). However, when qualitatively exploring how political polarization is measured (RQ3), we analyzed all articles together rather than in three separate groups.

Quantitative coding process

Two coders coded the papers on a variety of dimensions following a systematic codebook (Appendix 1). A research assistant was extensively trained and then read through each paper – coding a variety of categories: year of publication, country of sample, whether the authors provided a definition of polarization, and if polarization was explicitly mentioned in hypotheses/research questions and/or in the methods section (e.g. as a measure). Finally, we coded what type of polarization was studied (i.e. ideological or affective).Footnote5

After the coder read all papers, the first author randomly selected 6 of the 94 articles using a random number generator, for each category that the research assistant coded for. This meant the first author randomly selected 6 articles and coded them on 1 category (e.g. Publication Year), then again randomly selected 6 articles and coded them on another dimension (e.g. Country of Sample), and so on. The first author coded approximately 6.38% of all codes. There was 93.94% agreement between the first author and research assistant (see ). All articles included in this review and their codes can be found here: https://osf.io/gb7z2/?view_only=4105ef9699d64887958da24d4785e69e.

Table 1. Intercoder agreement on 6 randomly selected articles from each coded dimension.

Results

Quantitative analysis

Analysis of time information

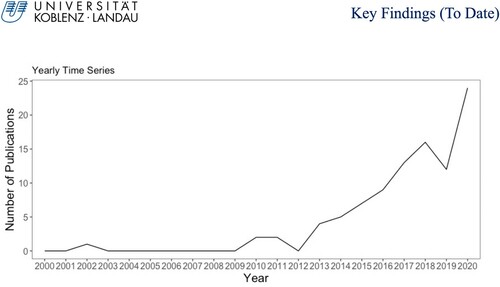

Answering RQ1a, the oldest relevant article was from 2002. Additionally, we observed a strong increase in publications in the last decade – suggesting growing interest in the academic community in exploring the role of media in political polarization,Footnote6 see . These trends in the increasing number of publications studying the role of media in political polarization could be based on the inherent yearly growth rate of published research (Bornmann & Mutz, Citation2015). However, we argue this increase is so large and abrupt (especially after 2012), that it may also be caused – in part – by increasing interest on the topic. We posit this increasing interest is related to the growing political divisions observed across many societies – especially the United States (Pew Research Center, Citation2017).

Country of sample

To assess RQ1b, we explored the types of samples used in this subset of studies. Our analysis revealed a hugely disproportional emphasis on samples from the United States (N = 81) – a trend seen throughout social science research (Arnett, Citation2016). The second largest number of samples came from South Korea (n = 6), a country known for polarization (Kim, Citation2015a), and partisan media (Lee, Citation2008). Additionally, there were many samples from European countries – where there is rising extremism (Koehler, Citation2016) and increasing use of social media by political campaigns (e.g. Baxter & Marcella, Citation2012; Jungherr, Citation2012). Countries included Germany (n = 4), the United Kingdom (n = 3), and Austria (n = 4) (see ). These results suggest an overemphasis on participants from Western societies (see appendix Table A1 for additional results).

Analysis of political polarization

To answer the quantitative component of RQ3, we assessed how polarization is defined and discussed in the literature. We found only about one-third of papers provided definitions of political polarization. We found that many did not make distinctions between ideological and affective polarization – rather using the term ‘political polarization’ to define either form of polarization.Footnote6This lack of a distinction makes the field’s understanding of political polarization muddled due to a lack of consensus in definitions of divergent forms of political polarization. We also examined the type of polarization assessed in each paper – finding a little more than half of the papers focused on ideological polarization, approximately one-third on affective polarization, and the rest examined both ideological and affective polarization.

Finally, we explored whether papers explicitly mentioned political polarization in the hypotheses and/or methods sections. While all papers were assessing political polarization (hence why they were included in our analyses), there was great variation in how polarization was discussed. For example, while a paper may discuss political polarization throughout the paper, they use terms such as ‘ideological extremity,’ or ‘sentiment towards opponents,’ to assess polarization in their hypotheses and methodology sections. Overall, less than half of the papers explicitly mentioned polarization in both their hypotheses and methods (see ). While it can be appropriate to use these synonyms, we encourage future researchers to use consistent terminology – ideally using terms like ideological or affective polarization – throughout their papers to aid in clarity for readers less familiar with the topic.

Table 2. Rate of polarization mentioned in hypotheses and methods across papers.

These quantitative analyses suggest that there has been a steep and abrupt increase in the last decade on research exploring the role of media in political polarization (especially within the United States), a trend in line with the increasing polarization plaguing many societies (e.g. many European societies). Additionally, results indicate a need for more clear differentiation between ideological and affective polarization in future research.

Qualitative analysis

For the qualitative analyses, we explore overarching themes in results across papers, we break down the analyses into three subsections: media contents, media exposure, media effects. Also, we explore the ways political polarization is measured across all studies.

Media contents

Research related to media content focuses on exploring the content of media sources, we assessed this research to answer RQ2a. Fourteen articles focused on media contents – conducting content analyses of social media posts and news content. These analyses primarily focused on the extent to which media content is politically polarized.

Social Media Content. Many studies assessed the extent to which the content on social media was polarized. Some of these studies focused on whether there are differences in content across media platforms. Two studies found that over time the content on Twitter (i.e. Tweets) became more affectively and ideologically (Marozzo & Bessi, Citation2017) polarized. However, other social media platforms (i.e. WhatsApp and Facebook) were associated with depolarization over time (Yarchi et al., Citation2020).

Other papers focused on the content produced by politicians. For example, one conducted content analyses of tweets by American politicians finding that Republican politicians used more polarizing language and rhetoric than Democratic counterparts (e.g. Russell, Citation2020). Another content analysis revealed that when politicians tweet more ideologically polarizing content, they receive more readership on Twitter (Hong & Kim, Citation2016). This suggests politicians may be incentivized to proclaim polarizing rhetoric to increase the spread of their message.

Additionally, two-thirds of analyses used Twitter data. We posit this is likely because it is easier for researchers to scrape data from Twitter than other platforms. While this data may be easier to collect, it is not clear whether these findings can be generalized to other social media platforms, or whether the levels of polarization observed on Twitter are similar on other platforms. Therefore, future research should more thoroughly consider alternate social media sites such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok.

Traditional Media Content. Fewer studies focused on the polarizing nature of content within the traditional news media context. Some studies focused on the differences between media programs. For example, one study found the content on Fox News was highly polarized, while NBC was not polarized (Hyun & Moon, Citation2016).

Another study focused on which politicians are most frequently covered by news media. Results indicated ideologically polarized politicians (i.e. politicians with a track record of voting along partisan lines) receive more news coverage (Wagner & Gruszcynski, Citation2018). Suggesting, like in the social media context, that polarization benefits politicians who seek media attention.

Multiple content analyses tracked polarization of news media over time – all finding that media content has become more polarized in recent years. However, we discovered a hyperfocus on climate change in these analyses (e.g. Chinn et al., Citation2020), with 3 of the 4 articles assessing news articles about climate change. These consistent findings provide strong evidence that the media is increasingly reporting in a polarized manner – though further analysis outside of the climate change context is needed, as relevant proportions of media consumers still use classic media outlets like television for news and political information (Newman et al., Citation2021).

Taken together, analysis of papers assessing the content of social and traditional media suggests a heavy focus on analyses of social media sources (especially Twitter), with evidence of polarized content online. However, these trends seem to be Twitter specific. Contrarily analyses related to the polarization of content on traditional media suggest high levels of polarized news media content – however we observe a hyperfocus on analyzing content about climate change. Additionally, studies focused on both social media and traditional media suggested politicians may benefit from being polarizing figures. Overall, in answering RQ2a, we find that content on social media and traditional media is becoming increasingly polarized.

Media exposure

While the content of media has an impact on political polarization, so too can ones’ exposure to the media source. There are two types of media exposure; pre-selective exposure (decisions made outside of the viewers discretion; e.g. algorithms) and selective exposure (decisions made by the viewer). A minority of studies had a pre-selection focus. Taken together, the papers suggested increased traditional media penetration can reduce ideological polarization (e.g. Darr et al., Citation2018; Melki & Pickering, Citation2014). However, to answer RQ2b, we concentrate our attention on the much larger subset of media exposure effects – selective exposure.

Social Media Use and Polarization. A majority of papers focused on the effects of selectively exposing oneself to social media content on political polarization. These studies showed that social media use predicted both ideological and affective polarization (Cho et al., Citation2018). However, some suggest the effect of social media use and polarization is small (Johnson et al., Citation2017), and that it is not about what we see on social media, but rather what we choose to share on social media that drives political polarization (Johnson et al., Citation2020). Others find real-world implications for social media use, showing that social media use is linked to participation in polarizing political protests (Chang & Park, Citation2020). Also, some research suggests a reciprocal relationship between media exposure and increased political polarization (Chang & Park, Citation2020).

However, not all research supports this link between social media use and increased political polarization. Two studies suggest there is no effect of social media on polarization (e.g. Valenzuela et al., Citation2019). However, neither examined Twitter or Facebook, the two primary social media sites where people see political information (e.g. Stier et al., Citation2018). One study found evidence of depolarizing effects on social media (i.e. Facebook), due to exposure to diverse information (Beam et al., Citation2018).

Given these divergent findings, the true effect of social media exposure on political polarization remains unclear. It seems in some cases social media exposure may exacerbate polarization while in other contexts or on certain platforms the effects are unobservable or even lead to depolarization. Future research should consider more clearly defining the conditions where selective exposure to social media exacerbates political polarization.

Traditional Media Use and Polarization. Selective exposure of traditional news media was also frequently linked to increased ideological (e.g. van Dalen,Citation2021) and affective (e.g. Kim & Zhou, Citation2020) political polarization. Additionally, all studies that focused specifically on selective exposure to partisan media found that these media sources predicted increased ideological and affective polarization (Melki & Sekeris, Citation2019). There was some evidence of a reciprocal effect between partisan news use and affective polarization (Stroud, Citation2010).

Yet not all findings were in agreement with this link between traditional media and political polarization. Several papers found no effect between traditional media and polarization (e.g. Udani et al., Citation2018), and one study suggested that while partisan media predicts affective polarization, mainstream media does not (Johnson & Lee, Citation2015).

Similar to the results related to selective exposure to social media, there is a lack of clarity regarding the impacts of selectively exposing oneself to traditional media content. While consistently exposure to partisan media predicted increased political polarization – there were inconsistent findings on the impact of mainstream media. Future research should consider further testing the conditions in which exposure to mainstream media predicts ideological and affective polarization.

Selective Exposure to Pro-Attitudinal Information. Some papers focused on the effects of selectively exposing oneself to like-minded (i.e. pro-attitudinal) media. All articles focused on these effects found it increased both ideological (e.g. Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Citation2015) and affective (e.g. Kim, Citation2015b) polarization. No studies found a null effect (or a depolarization effect) between selective exposure to pro-attitudinal information and political polarization – suggesting widespread agreement regarding the impact of likeminded media. These findings provide consistent evidence that exposure to pro-attitudinal news content is a driving force in political polarization.

Selective Exposure to Counter-Attitudinal Information. Some studies explored the effect of selective exposure to counter-attitudinal information. Results were more mixed than findings regarding pro-attitudinal information. Some suggested counter-attitudinal information exposure can help to decrease ideological and affective polarization (e.g. Kim, Citation2015b). However, others observe a backfire effect, where exposure to counter-attitudinal information actually increased ideological polarization (Kim, Citation2019), and under certain circumstances increased affective polarization (Garrett et al., Citation2014).

Taken together, and answering RQ2b the research suggests that selective exposure to (social) media tends to increase both ideological and affective polarization, and partisan media is especially polarizing. One finding is consistent – like-minded media makes people more ideologically and affectively polarized. Contrarily, it is less clear whether exposure to counter-attitudinal media increases (or hinders) polarization. Furthermore, we know very little about how media exposure influences depolarizing processes (Beam et al., Citation2018).

Media effects

A third set of studies directly explored the effect of media on polarization, which helped us answer RQ2c. These articles employed experiments, manipulating media to explore how media can shape political polarization.

Effects of Social Media. Some studies experimentally explored how social media can predict polarization. All experiments found that social media can further ideologically polarize people. Studies found that exposure to negative Tweets about candidates (Banks et al.,Citation2021), uncivil Facebook comments (Kim & Kim, Citation2019), and counter-attitudinal Twitter posts (Heiss et al., Citation2019) made people more ideologically polarized. Some studies explored ideological differences, finding Republicans, but not Democrats, exposed to counter-attitudinal content became more ideologically polarized (Bail et al., Citation2018). No experiments provided insights into ways social media can decrease (or have no effect) on ideological polarization.

Regarding affective polarization, nearly all experiments found that social media can further affectively polarize people. Researchers found that YouTube algorithm recommendations (Cho et al., Citation2020), and exposure to social media comments that derogate political adversaries (Suhay et al., Citation2018) increases affective polarization. Additionally, one study found those who deactivated their Facebook account in the lead up to the 2018 United States midterm election became less affectively polarized (Allcott et al., Citation2020). No experiments provided insights into ways social media can decrease (or have a null effect) on affective polarization.

Here we find agreement across studies that social media, in a variety of contexts, can exacerbate both ideological and affective political polarization.

Effects of Traditional Media Reporting. Multiple experiments also explored how traditional media can predict polarization. In terms of ideological polarization, ideological talk shows tend to increase this form of polarization (Arceneaux et al., Citation2013). However, hearing from fact checkers (Hameleers & van der Meer, Citation2020), and counter-attitudinal content (Lee, Citation2017) reduced ideological polarization.

Regarding affective polarization, most studies found that traditional media predicted increased affective polarization. Reading a news article about an in-party scandal (Rothschild et al.,Citation2021), having a highly diverse media environment alongside exposure to negative political ads (Lau et al., Citation2017), being exposed to likeminded (vs. cross-cutting) news media (Levendusky, Citation2013), and incivility on news media from out-party sources (Druckman et al., Citation2019), were associated with increased affective polarization. However, some researchers’ experimental manipulations decreased affective polarization. For example, highlighting group norms of open-mindedness incited increased willingness to read counter-attitudinal news articles, subsequently reducing affective polarization (Wojcieszak et al., Citation2020). Further, incivility from in-party news sources was associated with affective depolarization (Druckman et al., Citation2019). Others found no link between listening to like-minded radio shows and affective polarization (Conroy-Krutz & Moehler, Citation2015).

Several experiments assessed the effects of news coverage on polarization or partisan conflict, finding mixed results. Many found that news coverage of polarization or partisan conflict can actually make ideological and affective polarization worse (e.g. McLaughlin, Citation2018). However, others have found no such effects on ideological (Robinson & Mullinix, Citation2016) or affective (Kim & Zhou, Citation2020) polarization. The fact that media coverage on polarization (or partisan conflict) can actually cause people to become more polarized is a serious concern as journalists may unintentionally cause further political strife when attempting to highlight the effects of polarization on society.

Taken together, these results point to several key takeaway messages. First, the effect of social media on polarization seems consistent. In experimental settings, social media predicts both ideological and affective polarization. Additionally, in experimental settings, traditional media frequently predicts political polarization. However, some studies observe depolarization effects (Wojcieszak et al., Citation2020), shedding light on possible interventions for reducing polarization. Finally, when media discusses polarization (e.g. in news articles), frequently people become even more polarized, though these results are not consistent across papers. These results suggest a need for further exploration into what factors make media coverage about polarization, polarize viewers further and how media can be used to reduce political polarization.

Polarization measurement

To answer the qualitative components of RQ3, we assess how researchers measure polarization, exploring whether there is consistency in the ways ideological and affective polarization are measured. In terms of how ideological polarization is measured in surveys and experiments, the most common types of measurement include Likert scales where people report the extent to which they are liberal or conservative (e.g. Melki & Sekeris, Citation2019), or the extent to which they support/agree or do not support/agree (with) a specific political topic (e.g. climate change; Newman et al., Citation2018). While a majority of articles measured ideological polarization either based on placement on an ideology scale or based on participant stance on a political topic, and both forms of measurement are well-established in the field (e.g. Abramowitz & Saunders, Citation2008; Fiorina et al., Citation2005; Lelkes, Citation2016), these are distinct measures from one another. Ideological placement on a Likert scale is not necessarily synonymous with how one views a specific issue. One may feel they are slightly left leaning, and thus place themselves near the middle on a Likert ideology scale, and thereby be deemed as not ideologically polarized. Contrarily, that same individual may be strongly opinionated about a specific topic (e.g. abortion), and when asked whether they agree or disagree with abortion, could choose a much more extreme scale point, in turn being deemed as ideologically polarized. While we do not argue that either measurement has inherent flaws, and we know that increasingly people’s ideological identities and issue positions are in-line with one another (Levendusky, Citation2009), we caution researchers from making direct comparisons between these distinct forms of measurement.

In terms of affective polarization, many followed standard measures developed by Iyengar and colleagues (Citation2012), using warmth/favorability ratings of political allies vs. political opponents (e.g. Garrett et al.,Citation2019). In some cases, participants were asked to rate groups of people (e.g. Democrats and Republicans, Beam et al., Citation2018), and in other cases they were asked to rate specific people (e.g. presidential candidates; Min & Yun, Citation2018). However, others used measures that diverged from this, including the extent to which people viewed gubernatorial candidates as ‘a strong leader’ (Johnson & Lee, Citation2015), and the positive and negative sentiment used in Tweets about political allies and opponents (Yarchi et al., Citation2020), or one’s own positive/negative emotional valence before and after seeing a video of a politician (Cho et al., Citation2020). Additionally, Lau and colleagues (Citation2017) focused on vote choice preference between candidates, a measure typically associated with assessing ideological polarization (e.g. van Dalen,Citation2021).

Summary of Polarization Measurement. While there is consistency in the ways in which ideological polarization is measured, we find great diversity in how affective polarization is assessed. We suggest future research focus on using more standard measures of affective polarization (e.g. warmth and favorability ratings), to ensure researchers measure the same construct, in order to make cross-study comparisons more reliable.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we gathered articles assessing how (social) media shapes ideological and affective polarization. We find an increasing interest in the topic, with most articles being published since Prior’s Citation2013 landmark review – highlighting the need for a re-assessment like the one we have done here. Based on our review, we have 4 takeaway messages.

First, our quantitative analyses revealed a steep increase in research on political polarization; especially, an abrupt increase in research starting in 2012. One explanation for this increasing interest is related to the growing political divisions observed across many societies in Asia, Europe, and the United States (Pew Research Center, Citation2017). That being said, interest in political polarization seems to be especially high in the United States, as we see an overabundance of American samples. While it is important to understand this phenomenon in a society as polarized as the United States, it remains unclear if the multitude of studies conducted in the American context are generalizable internationally. For instance, can such results be generalized to countries with less commercially dominated media systems and strong Public Service Broadcasting? (Bos et al., Citation2016). We encourage future research in this field to consider the role of media in polarization outside of the American context.

Second, and arguably one of the most intriguing findings of these analyses, is that political polarization is not consistently discussed, or measured, across the literature. Approximately two-thirds of the articles do not provide a definition of political polarization. Many do not explicitly state whether they are assessing ideological or affective polarization, rather just using the term ‘political polarization.’ We argue this differentiation matters, these constructs are distinct from one another, and thus should not be umbrellaed together. In line with these findings, less than half of the articles explicitly mentioned polarization in their hypotheses and methods sections – instead using other terms (e.g. ‘sentiment towards opponents,’ or ‘ideological extremity’). While it can be appropriate to use synonyms when describing political polarization, we encourage future research to use more consistent terminology (thus improving clarity) when describing their research.

In terms of measurement of political polarization, we found researchers consistently measure ideological polarization in one of two ways – either through ideological placement measures or through participants reporting their stance on a political topic. We caution future researchers from viewing these two constructs as entirely comparable. While often both constructs are related due to political sorting (Levendusky, Citation2009), this is not always the case – leading to ill-founded comparisons between research measuring ideological polarization in divergent ways. In terms of affective polarization, we find most use warmth/favorability ratings, however others use very different constructs (e.g. strength of leaders). Again, we caution researchers from assuming these measures are entirely comparable to one another.

Taken together, the variability of measurement highlights the benefits of a systematic review, rather than a meta-analysis examining effect sizes. While meta-analyses are useful for taking a snapshot of the current state of the literature, it is nearly impossible for us to do so due to inconsistencies in measurement, as we are unable to reliably compare studies’ observed effects. Future work in this field should use more consistent measures of polarization so such meta-analyses are feasible.

Ideally future polarization research should include the following components:

(1). terminology; explicitly mention (and define) what type of polarization is studied (e.g. ideological),

(2). using this term explicitly in the hypotheses and methods sections (e.g. ‘ideological polarization’)

(3). choosing a standard measurement based on previous literature (e.g. 7-point Likert assessing the extent to which participants support (or do not support) a policy).

Third, our quantitative analyses of the content of media highlighted an intense focus on analyzing Twitter. While this is likely due to the ease at which researchers can scrape data from Twitter as compared to other social networking sites – it makes it difficult to understand whether similar trends occur on other social media platforms. Future research should focus on the role other social media platforms have in shaping polarization. Given Facebook’s penetration across the globe (Tankovska, Citation2021a), and much larger user base than Twitter (Tankovska, Citation2021b), we especially recommend further examination of how this platform shapes political polarization. Additionally, researchers exploring the content of traditional media outlets should consider conducting content analyses on newspaper articles and news on television that do not discuss climate change. Our analyses revealed a focus of assessing climate change news articles, leaving it unclear whether the increasing trend of polarized content in news extends to other political discussions.

Finally, our qualitative analysis revealed many studies exploring the key pillars of communication research; media content, media exposure (e.g. selective exposure), and media effects. We found the literature unanimously agrees that exposure to like-minded media increases polarization. However, there is less agreement on the role of counter-attitudinal media in political polarization. Some suggest counter-attitudinal content mitigates polarization (Kim, Citation2015b), by introducing viewers to diverging ideas that may make them reconsider their own attitudes – hence reducing polarization. Contrarily, others suggest this content exacerbates polarization (Kim, Citation2019), causing a backfire effect where people become even more entrenched in their belief systems, and thus more polarized. Future research should test in which circumstances counter-attitudinal media drives (or minimizes) polarization. We find that most studies find a link between selective exposure to (social) media and political polarization and that most experiments find that media exacerbates both ideological and affective polarization – though future research should also consider the effect of visuals in media contexts (von Sikorski, Citation2021). These results are concerning as all studies assessing the polarization of media content over time find that news media (e.g. Chinn et al., Citation2020) and social media (e.g. Marozzo & Bessi, Citation2017) are increasingly becoming partisan and polarized. This suggests that users and viewers of media may continue to become increasingly ideologically and affectively polarized in the years to come.

While there is great diversity in the focus of studies exploring the role of (social) media on political polarization, there is one glaring gap in the literature – a focus on how media can reduce or at the very least not increase political polarization – though some experiments highlighted potential avenues (e.g. Wojcieszak et al., Citation2020). We recommend future research continues to explore ways media can be used as a tool to minimize polarization, rather than exacerbate it. Furthermore, precise knowledge about the ways that media coverage shapes polarization may be particularly beneficial to those working in the newsroom, as journalists may be unaware of how certain media coverage can further divide viewers.

While this review provides unique insights into the literature on media and polarization, it also has limitations. We focused solely on peer-reviewed quantitative articles, meaning theoretical and qualitative articles were not included in our assessment of the literature. Our focus on quantitative papers allowed for identical coding for each article (e.g. country of sample). However, this did not allow us to consider the full breadth of scholarly knowledge on this topic – a limitation that should be considered when interpreting our results.

Conclusion

This review provides a valuable assessment of the state of the literature. We find an increased interest in examining the role of (social) media in political polarization and highlight the need to more clearly define (and measure) political polarization. Further, we call on future research to consider using (social) media as a tool to reduce political polarization in the public and to provide those in the newsroom with more insights and evidence-based information on how to prevent media coverage from unwittingly increasing polarization. Political polarization is a challenge likely to continue to affect society for the foreseeable future, however, we believe continuing to research the ways media can exacerbate (or hinder) political polarization can provide meaningful knowledge on the best ways to heal our political divisions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Political polarization can further be divided into elite polarization – where party elites (e.g. politicians and party leaders) are polarized (Hetherington, Citation2001) and mass polarization – where the greater public (e.g. average citizens) are polarized (Abramowitz & Saunders, Citation2008). While this is an important distinction to make, for the current research we do not focus on one form of polarization over the other. This is because elite and mass polarization can become intertwined within mediated contexts. For example, the (polarized) masses can read a news article about polarized political elites or a political elite can share a polarizing Tweet created by an average citizen.

2 We also coded for type of methodology used, type of sample (e.g. convenience), and media type and political topic assessed. Results for these findings can be found in the appendix.

3 We also searched for papers with the alternate spelling of “Polarisation”. This search produced the same 751 articles.

4 Several papers were published online by July 2020 however the printed version was published in 2021. We now cite the printed versions of these papers.

5 We additionally gathered more qualitative information. While coding each article, the research assistant also summarized each papers’ key findings in a few sentences. We used these summaries in our qualitative analysis – looking for overarching patterns (or inconsistencies) in the collected research articles.

6 While publishing papers exploring the role of media in political polarization seems to be a recent trend, years of data collection were much less homogenous. Multiple studies used longitudinal data spanning back into the twentieth century. However, a majority of data collected was still collected within the last 10 to 15 years – suggesting much of what we know about the role of media in political polarization is from recent data.

7 While we explore whether papers made a clear distinction between ideological and affective polarization – such a distinction was not possible for papers written before the concept of affective polarization was established in 2012 (Iyengar et al., Citation2012). Therefore, we also separately looked at papers written before 2012. All these papers focused on ideological polarization, and only 1 of these 5 papers provided a definition.

References

- Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (2008). Is polarization a myth? The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 542–555. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080493

- Ahmed, S., & Matthes, J. (2017). Media representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: A meta-analysis. International Communication Gazette, 79(3), 219–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516656305

- Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American Economic Review, 110(3), 629–676. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.2019060658

- Arceneaux, K., Johnson, M., & Cryderman, J. (2013). Communication, persuasion, and the conditioning value of selective exposure: Like minds may unite and divide but they mostly tune out. Political Communication, 30(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2012.737424

- Arnett, J. J. (2016). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist, 63(7), 602–614. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/19.1037/0003-066X.63.7.602

- Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Fallin Hunzaker, M. B., Lee, J., Mann, M., Merhout, F., & Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), 9216–9221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804840115

- Banks, A., Calvo, E., Karol, D., & Telhami, S. (2021). #Polarizedfeeds: Three experiments on polarization, framing, and social media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(3), 609–634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220940964

- Baxter, G., & Marcella, R. (2012). Does Scotland ‘like’ this? Social media use by political parties and candidates in Scotland during the 2010 UK general election campaign. Libri, 62(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2012-0008

- Beam, M. A., Hutchens, M. J., & Hmielowski, J. D. (2018). Facebook news and (de)polarization: Reinforcing spirals in the 2016 election. Information, Communication, & Society, 21(7), 940–958. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1444783

- Bornmann, L., & Mutz, R. (2015). Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometrics analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(11), 2215–2222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23329

- Bos, L., Kruikemeier, S., & de Vreese, C. (2016). Nation binding: How public service broadcasting mitigates political selective exposure. PLOS ONE, 11(5), e0155112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155112

- Chang, K., & Park, J. (2020). Social media use and participation in dueling protests: The case of the 2016-2017 presidential corruption scandal in South Korea. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(3), 547–567. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220940962.

- Chinn, S., Hart, P. S., & Soroka, S. (2020). Politicization and polarization in climate change news content, 1985-2017. Science Communication, 42(1), 112–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547019900290

- Cho, J., Ahmed, S., Hilbert, M., Liu, B., & Luu, J. (2020). Do search algorithms endanger democracy? An experimental investigation of algorithm effects on political polarization. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 64(2), 150–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08338151.2020.1757365

- Cho, J., Ahmed, S., Kerum, H., Choi, Y. J., & Lee, J. H. (2018). Influencing myself: Self-reinforcement through online political expression. Communication Research, 45(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216644020

- Conroy-Krutz, J., & Moehler, D. C. (2015). Moderation from bias: A field experiment on partisan media in a new democracy. The Journal of Politics, 77(2), 575–587. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/680187

- Dalton, R. J. (1987). Generational change in elite political beliefs: The growth of ideological polarization. The Journal of Politics, 49(4), 976–997. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2130780

- Darr, J. P., Hitt, M. P., & Dunaway, J. L. (2018). Newspaper closures polarize voting behavior. Journal of Communication, 68(6), 1007–1028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy051

- DellaVigna, S., & Kaplan, E. (2007). The Fox News effect: Media bias and voting. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1187–1234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1187

- Druckman, J. N., Gubitz, S. R., Levendusky, M. S., & Lloyd, A. M. (2019). How incivility on partisan media (de)polarizes the electorate. The Journal of Politics, 81(1), 291–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/699912

- Finkel, E. J., Bail, C. A., Cikara, M., Ditto, P. H., Iyengar, S., Klar, S., Mason, L., McGrath, M. C., Nyhan, B., Rand, D. G., Skitka, L. J., Tucker, J. A., Van Bavel, J. J., Wang, C. S., & Druckman, J. N. (2020). Political sectarianism in America: A poisonous cocktail of othering, aversion, and moralization poses a threat to democracy. Science, 370(6516), 533–536. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe1715

- Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J., & Pope, J. C. (2005). Culture War? The myth of a polarized America. Pearson Longman.

- Frimer, J. A., Skitka, L. J., & Motyl, M. (2017). Liberals and conservatives are similarly motivated to avoid exposure to one another’s opinions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.04.003

- Gaertner, S. L., Docido, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The common in-group identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000004

- Garrett, R. K., Gvirsman, S. D., Johnson, B. K., Tsfati, Y., Neo, R., & Dal, A. (2014). Implications of pro- and counter attitudinal information exposure for affective polarization. Human Communication Research, 40(3), 309–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12028

- Garrett, R. K., Long, J. A., & Jeong, M. S. (2019). From partisan media to misperception: Affective polarization as mediator. Journal of Communication, 69(5), 490–512. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz028

- Gidron, N., Adams, J., & Horne, W. (2019). Toward a comparative research agenda on affective polarization in mass publics. APSA Comparative Politics Newsletter, 29, 30–36.

- Hameleers, M., & van der Meer, T. G. L. A. (2020). Misinformation and polarization in a high-choice media environment: How effective are political fact-checkers. Communication Research, 47(2), 227–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009650218819671

- Hare, C., & Poole, K. T. (2014). The polarization of contemporary American politics. Polity, 46(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2014.10

- Heaney, M. T., Masket, S. E., Miller, J. M., & Strolovitch, D. Z. (2012). Polarized networks: The organizational affiliations of national party convention delegates. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(12), 1654–1676. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764212463354

- Heatherington, M. J. (2001). Resurgent mass partisanship: The role of elite polarization. American Political Science Review, 95(3), 619–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055401003045

- Heiss, R., von Sikorski, C., & Matthes, J. (2019). Populist Twitter posts in news stories. Journalism Practice, 13(6), 742–758. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1564883

- Hong, S., & Kim, S. H. (2016). Political polarization on Twitter: Implications for the use of social media in digital governments. Government Information Quarterly, 33(4), 777–782. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.04.007.E13

- Hyun, K. D., & Moon, S. (2016). Agenda setting in the partisan TV news context: Attribute agenda setting and polarized evaluation of presidential candidates among viewers of NBC, CNN, and Fox News. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(3), 509–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016628820

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038

- Johnson, B. K., Neo, R. L., Heinen, M. E. M., Smits, L., & van Veen, C. (2020). Issues, involvement, and influence: Effects of selective exposure and sharing on polarization and participation. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1916/j.chb.2019.09.031

- Johnson, T. J., Kaye, B. K., & Lee, A. M. (2017). Blinded by the spite? Path model of political attitudes, selectivity, and social media. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 25(3), 181–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2017.1324454

- Johnson, T. J., & Lee, A. M. (2015). Kick the bums out?: A structural equation model exploring the degree to which mainstream and partisan sources influence polarization and anti-incumbent attitudes. Electoral Studies, 40, 210–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.08.008

- Jones, D. A. (2002). The polarizing effect of new media messages. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14(2), 158–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/12.2.158

- Jones, D. R. (2001). Party polarization and legislative gridlock. Political Research Quarterly, 54(1), 125–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290105400107

- Jungherr, A. (2012). Online campaigning in Germany: The CDU online campaign for the general election 2009 in Germany. German Politics, 21(3), 317–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2012.716043

- Jurkowitz, M., Mitchell, A., Shrearer, E., & Walker, M. (2020). U.S. media polarization and the 2020 election: A nation divided. Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 26, 2021 from https://www.journalism.org/2020/01/24/u-s-media-polarization-and-the-2020-election-a-nation-divided/.

- Kim, S. Y. (2015a). Polarization, partisan bias, and democracy: Evidence from the 2012 Korean presidential election panel data. Journal of Democracy and Human Rights, 15(3), 459–491.

- Kim, Y. (2015b). Does disagreement mitigate polarization? How selective exposure and disagreement affect polarization. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(4), 915–937. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015596328

- Kim, Y. (2019). How cross-cutting news exposure relates to candidate issue stance knowledge, political polarization, and participation: The moderating role of political sophistication. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 31(4), 626–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edy032

- Kim, Y., & Kim, Y. (2019). Incivility on Facebook and political polarization: The mediating role of seeking further comments and negative emotion. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 219–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10-1016/j.chb.2019.05.022

- Kim, Y., & Zhou, S. (2020). The effects of political conflict news frame on political polarization: A social identity approach. International Journal of Communication, 14, 937–958.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Mothes, C., Johnson, B. K., Westerwick, A., & Donsbach, W. (2015). Political online information searching in Germany and the United States: Confirmation bias, source credibility, and attitude impacts. Journal of Communication, 65(3), 489–511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12154

- Koehler, D. (2016). Right-wing extremism and terrorism in Europe. Prism, 6(2), 84–105.

- Kubin, E., Puryear, C., Schein, C., & Gray, K. (2021). Personal experiences bridge moral and political divides better than facts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2008389118

- Lau, R. R., Andersen, D. J., Ditonto, T. M., Kleinberg, M. S., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2017). Effect of media environment diversity and advertising tone on information search, selective exposure, and affective polarization. Political Behavior, 39(1), 231–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9354-8

- Lee, F. E. (2015). How party polarization affects governance. Annual Review of Political Science, 18(1), 261–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-072012-113747

- Lee, J. (2008). Korean journalism and social conflict. Communication Theories, 4(2), 48–72.

- Lee, S. (2017). Implications of counter-attitudinal information exposure in further information-seeking and attitude change. Information Research, 22(3), 1–14.

- Lelkes, Y. (2016). Mass polarization: Manifestations and measurements. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 392–410. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw005

- Levendusky, M. (2013). Partisan media exposure and attitudes toward the opposition. Political Communication, 30(4), 565–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2012.737435

- Levendusky, M. S. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals become democrats and conservatives become republicans. University of Chicago Press.

- Li, K., Rollins, J., & Yan, E. (2018). Web of Science use in published research and review papers 1997–2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Scientometrics, 115(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2622-5

- Marozzo, F., & Bessi, A. (2017). Analyzing polarization of social media users and news sites during political campaigns. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 8(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-017-0479-5

- Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. University of Chicago Press.

- McLaughlin, B. (2018). Commitment to the team: Perceived conflict and political polarization. Journal of Media Psychology, 30(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000176

- Melki, M., & Pickering, A. (2014). Ideological polarization and the media. Economics Letters, 125(1), 36–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.08.008

- Melki, M., & Sekeris, P. (2019). Media-driven polarization: Evidence from the US. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 13(2019-34), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2019-3

- Min, H., & Yun, S. (2018). Selective exposure and political polarization of public opinion on the presidential impeachment in South Korea: Facebook vs. KakaoTalk. Korea Observer – Institute of Korean Studies, 49(1), 137–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.29152/KOIKS.2018.49.1.137

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Schulz, A., Andi, S., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2021). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-06/Digital_News_Report_2021_FINAL.pdf.

- Newman, T. P., Nisbet, E. C., & Nisbet, M. C. (2018). Climate change, cultural cognition, and media effects: Worldviews drive news selectivity, biased processing, and polarized attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 27(8), 985–1002. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662518801170

- Pew Research Center. (2017). The partisan divide on political values grows even wider. Retrieved March 9 2021, from https://www.people-press.org/2017/10/05/the-partisan-divide-on-political-values-grows-even-wider/.

- Pew Research Center. (2019). Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/.

- Prior, M. (2013). Media and political polarization. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 101–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135242

- Robinson, J., & Mullinix, K. J. (2016). Elite polarization and public opinion: How polarization is communicated and it's effect. Political Communication, 33(2), 261–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1055526

- Rothschild, Z. K., Keefer, L. A., & Hauri, J. (2021). Defensive partisanship? Evidence that in-party scandals increase out-party hostility. Political Psychology, 42(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12680

- Russell, A. (2020). Minority opposition and asymmetric parties? Senators' partisan rhetoric on Twitter. Political Research Quarterly, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912920921239

- Stier, S., Bleier, A., Lietz, H., & Strohmaier, M. (2018). Election campaigning on social media: Politicians, audiences, and the mediation of political communication on Facebook and twitter. Political Communication, 35(1), 50–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/105846009.2017.1334728

- Stroud, N. J. (2010). Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 556–576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01497.x

- Suhay, E., Bello-Pardo, E., & Maurer, B. (2018). The polarizing effects of online partisan criticism: Evidence from two experiments. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740697

- Tankovska, H. (2021a). Percentage of global population using Facebook as of January 2020, by region. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/241552/share-of-global-population-using-facebook-by-region/.

- Tankovska, H. (2021b). Most popular social networks worldwide as of January 2021, ranked by number of active users. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics /272014/global-social networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/.

- Tsfati, Y., Boomgaarden, H. G., Strömbäck, J., Vliegenhart, R., Damstra, A., & Lindgren, E. (2020). Causes and consequences of mainstream media dissemination of fake news: Literature review and synthesis. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1759443

- Tucker, J. A., Guess, A., Barberá, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. Hewlett Foundation. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

- Udani, A., Kimball, D. C., & Fogarty, B. (2018). How local media coverage of voter fraud influences partisan perceptions in the United States. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 18(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440018766907

- Valenzuela, S., Bachmann, I., & Bargsted, M. (2019). The personal is the political? What do WhatsApp users share and how it matters for news knowledge, polarization and participation in Chile. Digital Journalism, 9(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1693904

- Van Aelst, P., Strömbäck, J., Aalberg, T., Esser, F., de Vreese, C., Matthes, J., Hopmann, D., Salgado, S., Hubé, N., Stępińska, A., Papathanassopoulos, S., Berganza, R., Legnante, G., Reinemann, C., Sheafer, T., & Stanyer, J. (2017). Political communication in a high-choice media environment: A challenge for democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association, 41(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551

- van Dalen, A. (2021). Red economy, blue economy: How media-party parallelism affects the partisan economic perception gap. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(2), 385–409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220926931

- von Sikorski, C. (2018). The aftermath of political scandals: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Communication, 12, 3109–3133.

- von Sikorski, C. (2021). Visual polarization: Examining the interplay of visual cues and media trust on the evaluation of political candidates. Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920987680

- Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 69, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

- Wagner, M. W., & Gruszcynski, M. (2018). Who gets covered? Ideological extremity and news coverage of members of the US Congress, 1993 to 2013. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 95(3), 670–690. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699017702836

- Wojcieszak, M., Winter, S., & Yu, C. (2020). Social norms and selectivity: Effects of open-mindedness on content selection and affective polarization. Mass Communication and Society, 23(4), 455–483. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2020.1714663

- Yarchi, M., Baden, C., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2020). Political polarization on the digital sphere: A cross-platform, over-time analysis of interaction, positional, and affective polarization on social media. Political Communication, 38(1–2), 98–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1785067

Appendices

Appendix 1

Codebook

Please see appendix Table A1 for a detailed breakdown of codes.

Year of publication

The publication year of the paper was recorded with 1 count for that appropriate year. For example, if a paper was published in 2019, 1 count was added to 2019.

Country of sample

The country the sample was recruited from (by study) was recorded with 1 count for the appropriate country. For example, if a study’s sample was from Austria, Austria would receive 1 count. If a paper had 2 studies, 1 in which the sample was from the U.S., and the other in which the sample was from Israel, each country would receive 1 count. Further, if a sample had 3 studies, and each study had a Dutch sample, 3 counts were added to the Netherlands, as we analyzed this dimension by a study rather than by paper. In analyses, there were several cases in which one study included both a content analysis (e.g. from the U.S.) and a survey (with U.S. participants), in these cases we only added 1 count to the United States instead of 2. In other studies, there were several samples from several countries, in these cases, 1 count was added to each of those countries. Several studies provided unclear or no information on where there sample was from, therefore in analyses we marked them as ‘Unclear/Unidentified.’

Type of sample

For all samples that included human participants (e.g. were not content analyses of Tweets or newspapers), we recorded what type of sample they were (i.e. representative vs convenience sample). As with the country of sample analysis, we analyzed this dimension by study rather than by paper. This meant if a paper had 2 studies, both of which were convenience samples, 2 counts would be added under convenience. If a paper had 2 studies, one of which was convenience and the other was a representative sample, 1 count would be added under convenience, and another under representative sample. If a paper had a study that included both a content analysis and a human sample in combination, 1 count would be added under the appropriate type of sample. Two studies used advanced analyses with multiple types of data and samples, making it impossible to categorize either of them, we marked these studies as ‘Other.’

Type of methodology

We coded methodology by study (rather than by paper). We recorded methodology type with the following options: content analysis, experiment, longitudinal/panel study, or survey. If a paper had two studies, 1 that was a survey and another that was an experiment, each methodology would receive 1 count. Some studies had multiple methodologies within 1 study (e.g. a content analysis in combination with a survey), in these cases both types of methodologies would receive a count (e.g. 1 count for content analysis and 1 count for survey). Two studies did not fit any of the aforementioned methodologies, in these cases we coded these options as ‘Other.’

Secondary Data. Additionally, we considered whether the study used secondary data. For each study that used secondary data (even if there were multiple secondary data sources within that 1 study), we added 1 count to the total count of studies using secondary data sources. Further, if a paper, for example, had 2 studies, and both of those studies used different secondary data sources, we added 2 to a total count of studies using secondary data sources, again because we were interested in analyzing this by study rather than by paper.

Political topic

We also evaluated the types of political issues studies focus on. For example, did the study analyze newspapers about climate change? Or experimentally manipulate Tweets about immigration? There were a wide variety of topics assessed or used by these studies, from the death penalty, to government spending, to political advertising, to candidate evaluations. We grouped studies with similar political themes together where appropriate. This analysis was done by a study rather than by paper. This means that if a paper had 2 studies, both of which focused on immigration, we would add 2 counts to the ‘Immigration/Refugee’ category. Further, some studies focused on multiple political issues, in these cases we added one count for each type of political topic.

Type of media

Finally, we evaluated what type of media the paper focused on. For example, were they interested in selective exposure to social media sites? Did they manipulate news articles? Similarly, to the political topic analyses, this analysis was done by study rather than by paper. This means that if a paper had 2 studies, both of which focused on broadcast news, we would add 2 counts to the ‘Broadcast News/Cable TV/ Political ad’ category. Further, some studies focused on multiple types of media (e.g. selective exposure to broadcast news, newspapers, and social media), in these cases, we added one count to all types of media (e.g. broadcast news, newspapers, social media).

Analysis of political polarization

For this dimension, we counted the number of papers that provided some kind of definition for polarization. During initial coding by the research assistant, it was coded whether a paper had a definition using the following coding scheme (1=Yes, 2=No). During the analysis we then counted up the total number of papers that included a definition.

Additionally, we coded for the type of polarization each paper assessed (ideological polarization, affective polarization, or both). The type of polarization assessed was determined based on the measures used in the paper. Measures focused on favorability/and likeability of ingroup and outgroup were considered as measuring affective polarization. Measures focused on a political stance or ideological position were considered as measuring ideological polarization. During the analysis, we focused on the type of polarization assessed by paper rather than by study, so for example if a paper had two studies, both of which assessed ideological polarization, this paper would receive 1 countfor measuring ideological polarization.

We also coded for whether papers mentioned polarization in their hypotheses and/or methods. When polarization was mentioned (i.e. ‘ideological polarization,’ ‘affective polarization,’ ‘political polarization,’ or ‘polarization’) in both hypotheses and methods, it was coded as a ‘yes,’ when polarization was mentioned in neither hypotheses or methods, it was coded as a ‘no.’ If a paper mentioned polarization in one but not the other (e.g. mentioned polarization in hypotheses but not in methods), this was noted by explicitly stating in which section polarization was mentioned and in which it was not (e.g. ‘hypotheses yes, methods no’).

Additional results

Qualitative analytic strategy with coded articles

As mentioned previously, we also conducted a more qualitative analysis in which the research assistant summarized the key findings from each paper in several sentences. With these summaries, we looked for overlapping themes to explore whether there were patterns in findings related to the role of media in political polarization. Note that for the qualitative analyses considered each of the paper categories separately (i.e. media contents, selective exposure, pre-selection, or media effects) to answer RQ2. This meant we looked for overarching patterns in findings of (1) papers that explored media contents, (2) papers that explored selective exposure to media, (3) papers focused on pre-selection, and (4) papers focused on media effects. Overall, we found consistency in findings, with very fewresults not being able to be grouped with findings from other papers.

To answer the qualitative component of RQ3, the research assistant copy and pasted the measurement of political polarization directly from the paper. We then looked for overlapping trends in how both ideological and affective polarization were measured throughout the literature.